From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

Sun is the

star at the center of the

Solar System. It is a nearly perfect sphere of hot

plasma, with internal

convective motion that generates a

magnetic field via a

dynamo process. It is by far the most important source of

energy for

life on

Earth. Its diameter is about 1.39 million kilometers, i.e. 109 times that of Earth, and

its mass is about 330,000 times that of Earth, accounting for about 99.86% of the total mass of the Solar System.

About three quarters of the Sun's mass consists of

hydrogen (~73%); the rest is mostly

helium (~25%), with much smaller quantities of heavier elements, including

oxygen,

carbon,

neon, and

iron.

The Sun is a

G-type main-sequence star (G2V) based on its

spectral class. As such, it is informally and not completely accurately referred to as a

yellow dwarf (its light is closer to white than yellow). It formed approximately 4.6 billion

[a][10][19] years ago from the

gravitational collapse of matter within a region of a large

molecular cloud. Most of this matter gathered in the center, whereas the rest flattened into an orbiting disk that

became the Solar System. The central mass became so hot and dense that it eventually initiated

nuclear fusion in its

core. It is thought that almost all stars

form by this process.

The Sun is roughly middle-aged; it has not changed dramatically for more than four billion

[a] years, and will remain fairly stable for more than another five billion years. It currently

fuses about 600 million tons of

hydrogen into

helium every second,

converting 4 million tons of matter into energy

every second as a result. This energy, which can take between 10,000

and 170,000 years to escape from its core, is the source of the Sun's

light and heat. In about 5 billion years, when

hydrogen fusion in its core has diminished to the point at which the Sun is no longer in

hydrostatic equilibrium,

the core of the Sun will experience a marked increase in density and

temperature while its outer layers expand to eventually become a

red giant. It is calculated that the Sun will become sufficiently large to engulf the current orbits of

Mercury and

Venus, and render

Earth uninhabitable. After this, it will shed its outer layers and become a dense type of cooling star known as a

white dwarf, which no longer produces energy by fusion, but still glows and gives off heat from its previous fusion.

The enormous effect of the Sun on Earth has been recognized since

prehistoric times, and the Sun has been

regarded by some cultures as a

deity. The

synodic rotation of Earth and its orbit around the Sun are the basis of

solar calendars, one of which is the predominant

calendar in use today.

Name and etymology

The English proper name

Sun developed from

Old English sunne and may be related to

south. Cognates to English

sun appear in other

Germanic languages, including

Old Frisian sunne,

sonne,

Old Saxon sunna,

Middle Dutch sonne, modern

Dutch zon,

Old High German sunna, modern German

Sonne,

Old Norse sunna, and

Gothic sunnō. All Germanic terms for the Sun stem from

Proto-Germanic *

sunnōn.

[20][21]

The Latin name for the Sun,

Sol, is used at times as another name for the Sun, but is not commonly used in everyday English.

Sol is also used by planetary astronomers to refer to the duration of a

solar day on another planet, such as

Mars.

[22]

The related word

solar is the usual

adjectival term used for the Sun,

[23][24] in terms such as

solar day,

solar eclipse, and

Solar System. A mean

Earth solar day is approximately 24 hours, whereas a mean Martian 'sol' is 24 hours, 39 minutes, and 35.244 seconds.

[25]

The English weekday name

Sunday stems from Old English (

Sunnandæg; "Sun's day", from before 700) and is ultimately a result of a

Germanic interpretation of Latin

dies solis, itself a translation of the Greek ἡμέρα ἡλίου (

hēméra hēlíou).

[26]

Religious aspects

Solar deities play a major role in many world religions and mythologies.

[27] The ancient

Sumerians believed that the sun was

Utu,

[28][29] the god of justice and twin brother of

Inanna, the

Queen of Heaven,

[28] who was identified as the planet

Venus.

[29] Later, Utu was identified with the

East Semitic god

Shamash.

[28][29] Utu was regarded as a helper-deity, who aided those in distress,

[28] and, in

iconography, he is usually portrayed with a long beard and clutching a

saw,

[28] which represented his role as the dispenser of justice.

[28]

From at least the

4th Dynasty of

Ancient Egypt, the Sun was worshipped as the

god Ra, portrayed as a falcon-headed divinity surmounted by the solar disk, and surrounded by a serpent. In the

New Empire period, the Sun became identified with the

dung beetle, whose spherical ball of dung was identified with the Sun. In the form of the Sun disc

Aten, the Sun had a brief resurgence during the

Amarna Period when it again became the preeminent, if not only, divinity for the

Pharaoh Akhenaton.

In

Proto-Indo-European religion, the sun was personified as the goddess

*Seh2ul.

[32][33][21] Derivatives of this goddess in

Indo-European languages include the

Old Norse Sól,

Sanskrit Surya,

Gaulish Sulis,

Lithuanian Saulė, and

Slavic Solntse.

[21] In

ancient Greek religion, the sun deity was the male god

Helios,

[32] but traces of an earlier female solar deity are preserved in

Helen of Troy.

[32] In later times, Helios was

syncretized with

Apollo.

[34]

In the

Bible,

Malachi 4:2 mentions the "Sun of Righteousness" (sometimes translated as the "Sun of Justice"),

[35] which some

Christians have interpreted as a reference to the

Messiah (

Christ).

[36] In ancient Roman culture,

Sunday was the day of the Sun god. It was adopted as the

Sabbath

day by Christians who did not have a Jewish background. The symbol of

light was a pagan device adopted by Christians, and perhaps the most

important one that did not come from Jewish traditions. In paganism, the

Sun was a source of life, giving warmth and illumination to mankind. It

was the center of a popular cult among Romans, who would stand at dawn

to catch the first rays of sunshine as they prayed. The celebration of

the

winter solstice (which influenced Christmas) was part of the Roman cult of the unconquered Sun (

Sol Invictus). Christian churches were built with an orientation so that the congregation faced toward the sunrise in the East.

[37]

Tonatiuh, the

Aztec god of the sun, was usually depicted holding arrows and a shield

[38] and was closely associated with the practice of

human sacrifice.

[38] The sun goddess

Amaterasu is the most important deity in the

Shinto religion,

[39][40] and she is believed to be the direct ancestor of all

Japanese emperors.

[39]

Characteristics

The Sun is a

G-type main-sequence star that comprises about 99.86% of the mass of the Solar System. The Sun has an

absolute magnitude of +4.83, estimated to be brighter than about 85% of the stars in the

Milky Way, most of which are

red dwarfs.

[41][42]

The Sun is a

Population I, or heavy-element-rich,

[b] star.

[43] The formation of the Sun may have been triggered by shockwaves from one or more nearby

supernovae.

[44] This is suggested by a high

abundance of heavy elements in the Solar System, such as

gold and

uranium, relative to the abundances of these elements in so-called

Population II, heavy-element-poor, stars. The heavy elements could most plausibly have been produced by

endothermic nuclear reactions during a supernova, or by

transmutation through

neutron absorption within a massive second-generation star.

[43]

The Sun is by far the brightest object in the Earth's sky, with an

apparent magnitude of −26.74.

[45][46] This is about 13 billion times brighter than the next brightest star,

Sirius, which has an apparent magnitude of −1.46. The mean distance of the Sun's center to Earth's center is approximately 1

astronomical unit (about 150,000,000 km; 93,000,000 mi), though the distance varies as Earth moves from

perihelion in January to

aphelion in July.

[47]

At this average distance, light travels from the Sun's horizon to

Earth's horizon in about 8 minutes and 19 seconds, while light from the

closest points of the Sun and Earth takes about two seconds less. The

energy of this

sunlight supports almost all life

[c] on Earth by

photosynthesis,

[48] and drives

Earth's climate and weather.

The Sun does not have a definite boundary, but its density decreases exponentially with increasing height above the

photosphere.

[49]

For the purpose of measurement, however, the Sun's radius is considered

to be the distance from its center to the edge of the photosphere, the

apparent visible surface of the Sun.

[50] By this measure, the Sun is a near-perfect sphere with an

oblateness estimated at about 9 millionths,

[51] which means that its polar diameter differs from its equatorial diameter by only 10 kilometres (6.2 mi).

[52]

The tidal effect of the planets is weak and does not significantly affect the shape of the Sun.

[53] The Sun rotates faster at its

equator than at its

poles. This

differential rotation is caused by

convective motion due to heat transport and the

Coriolis force

due to the Sun's rotation. In a frame of reference defined by the

stars, the rotational period is approximately 25.6 days at the equator

and 33.5 days at the poles. Viewed from Earth as it orbits the Sun, the

apparent rotational period of the Sun at its equator is about 28 days.

[54]

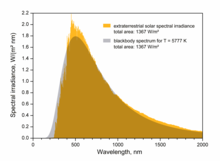

Sunlight

The

solar constant

is the amount of power that the Sun deposits per unit area that is

directly exposed to sunlight. The solar constant is equal to

approximately

1,368 W/m2 (watts per square meter) at a distance of one

astronomical unit (AU) from the Sun (that is, on or near Earth).

[55] Sunlight on the surface of Earth is

attenuated by Earth's atmosphere, so that less power arrives at the surface (closer to

1,000 W/m2) in clear conditions when the Sun is near the

zenith.

[56]

Sunlight at the top of Earth's atmosphere is composed (by total energy)

of about 50% infrared light, 40% visible light, and 10% ultraviolet

light.

[57] The atmosphere in particular filters out over 70% of solar ultraviolet, especially at the shorter wavelengths.

[58] Solar

ultraviolet radiation ionizes Earth's dayside upper atmosphere, creating the electrically conducting

ionosphere.

[59]

The Sun's color is white, with a

CIE

color-space index near (0.3, 0.3), when viewed from space or when the

Sun is high in the sky. When measuring all the photons emitted, the Sun

is actually emitting more photons in the green portion of the spectrum

than any other.

[60][61] When the Sun is low in the sky,

atmospheric scattering

renders the Sun yellow, red, orange, or magenta. Despite its typical

whiteness, most people mentally picture the Sun as yellow; the reasons

for this are the subject of debate.

[62]

The Sun is a

G2V star, with

G2 indicating its

surface temperature of approximately 5,778 K (5,505 °C, 9,941 °F), and

V that it, like most stars, is a

main-sequence star.

[63][64] The average

luminance of the Sun is about 1.88

giga candela per square metre, but as viewed through Earth's atmosphere, this is lowered to about 1.44 Gcd/m

2.

[d] However, the luminance is not constant across the disk of the Sun (

limb darkening).

Composition

The Sun is composed primarily of the

chemical elements hydrogen and

helium. At this time in the Sun's life, they account for 74.9% and 23.8% of the mass of the Sun in the photosphere, respectively.

[65] All heavier elements, called

metals

in astronomy, account for less than 2% of the mass, with oxygen

(roughly 1% of the Sun's mass), carbon (0.3%), neon (0.2%), and iron

(0.2%) being the most abundant.

[66]

The Sun's original chemical composition was inherited from the

interstellar medium out of which it formed. Originally it would have contained about 71.1% hydrogen, 27.4% helium, and 1.5% heavier elements.

[65] The hydrogen and most of the helium in the Sun would have been produced by

Big Bang nucleosynthesis in the first 20 minutes of the universe, and the heavier elements were

produced by previous generations of stars before the Sun was formed, and spread into the interstellar medium during the

final stages of stellar life and by events such as

supernovae.

[67]

Since the Sun formed, the main fusion process has involved fusing

hydrogen into helium. Over the past 4.6 billion years, the amount of

helium and its location within the Sun has gradually changed. Within the

core, the proportion of helium has increased from about 24% to about

60% due to fusion, and some of the helium and heavy elements have

settled from the photosphere towards the center of the Sun because of

gravity. The proportions of metals (heavier elements) is unchanged.

Heat is transferred outward from the Sun's core by radiation rather than by convection (see

Radiative zone below), so the fusion products are not lifted outward by heat; they remain in the core

[68]

and gradually an inner core of helium has begun to form that cannot be

fused because presently the Sun's core is not hot or dense enough to

fuse helium. In the current photosphere the helium fraction is reduced,

and the

metallicity is only 84% of what it was in the

protostellar

phase (before nuclear fusion in the core started). In the future,

helium will continue to accumulate in the core, and in about 5 billion

years this gradual build-up will eventually cause the Sun to exit the

main sequence and become a

red giant.

[69]

The chemical composition of the photosphere is normally

considered representative of the composition of the primordial Solar

System.

[70] The solar heavy-element abundances described above are typically measured both using

spectroscopy of the Sun's photosphere and by measuring abundances in

meteorites

that have never been heated to melting temperatures. These meteorites

are thought to retain the composition of the protostellar Sun and are

thus not affected by settling of heavy elements. The two methods

generally agree well.

[18]

Singly ionized iron-group elements

In the 1970s, much research focused on the abundances of

iron-group elements in the Sun.

[71][72] Although significant research was done, until 1978 it was difficult to

determine the abundances of some iron-group elements (e.g.

cobalt and

manganese) via

spectrography because of their

hyperfine structures.

[71]

The first largely complete set of

oscillator strengths of singly ionized iron-group elements were made available in the 1960s,

[73] and these were subsequently improved.

[74] In 1978, the abundances of singly ionized elements of the iron group were derived.

[71]

Isotopic composition

Various authors have considered the existence of a gradient in the

isotopic compositions of solar and planetary

noble gases,

[75] e.g. correlations between isotopic compositions of

neon and

xenon in the Sun and on the planets.

[76]

Prior to 1983, it was thought that the whole Sun has the same composition as the solar atmosphere.

[77] In 1983, it was claimed that it was

fractionation in the Sun itself that caused the isotopic-composition relationship between the planetary and solar-wind-implanted noble gases.

[77]

Structure and energy production

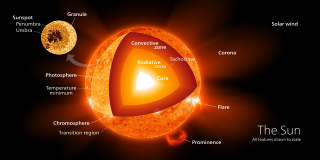

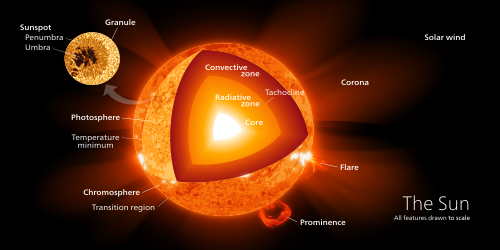

The structure of the Sun contains the following layers:

- Core - the innermost 20 - 25% of the Sun's radius, where temperature (energies) and pressure are sufficient for nuclear fusion

to occur. Hydrogen fuses into helium (which cannot currently be fused

at this point in the Sun's life). The fusion process releases energy,

and the helium gradually accumulates to form an inner core of helium

within the core itself.

- Radiative zone - Convection

cannot occur until much nearer the surface of the Sun. Therefore,

between about 20-25% of the radius, and 70% of the radius, there is a

"radiative zone" in which energy transfer occurs by means of radiation

(photons) rather than by convection.

- Tachocline - the boundary region between the radiative and convective zones.

- Convective zone - Between about 70% of the Sun's radius and a

point close to the visible surface, the Sun is cool and diffuse enough

for convection to occur, and this becomes the primary means of outward

heat transfer, similar to weather cells which form in the earth's

atmosphere.

- Photosphere - the deepest part of the Sun which we can

directly observe with visible light. Because the Sun is a gaseous

object, it does not have a clearly-defined surface; its visible parts

are usually divided into a 'photosphere' and 'atmosphere'.

- Atmosphere - a gaseous 'halo' surrounding the Sun, comprising the chromosphere, solar transition region, corona and heliosphere. These can be seen when the main part of the Sun is hidden, for example, during a solar eclipse.

Core

The

core of the Sun extends from the center to about 20–25% of the solar radius.

[78] It has a density of up to

150 g/cm3[79][80] (about 150 times the density of water) and a temperature of close to 15.7 million

kelvins (K).

[80] By contrast, the Sun's surface temperature is approximately 5,800 K. Recent analysis of

SOHO mission data favors a faster rotation rate in the core than in the radiative zone above.

[78] Through most of the Sun's life, energy has been produced by

nuclear fusion in the core region through a series of steps called the

p–p (proton–proton) chain; this process converts

hydrogen into

helium.

[81] Only 0.8% of the energy generated in the Sun comes from the

CNO cycle, though this proportion is expected to increase as the Sun becomes older.

[82]

The core is the only region in the Sun that produces an appreciable amount of

thermal energy

through fusion; 99% of the power is generated within 24% of the Sun's

radius, and by 30% of the radius, fusion has stopped nearly entirely.

The remainder of the Sun is heated by this energy as it is transferred

outwards through many successive layers, finally to the solar

photosphere where it escapes into space as sunlight or the

kinetic energy of particles.

[63][83]

The

proton–proton chain occurs around

9.2×1037 times each second in the core, converting about 3.7

×10

38 protons into

alpha particles (helium nuclei) every second (out of a total of ~8.9

×10

56 free protons in the Sun), or about 6.2

×10

11 kg/s.

[63] Fusing four free

protons (hydrogen nuclei) into a single

alpha particle (helium nucleus) releases around 0.7% of the fused mass as energy,

[84]

so the Sun releases energy at the mass–energy conversion rate of 4.26

million metric tons per second (which requires 600 metric megatons of

hydrogen

[85]), for 384.6

yottawatts (

3.846×1026 W),

[1] or 9.192

×10

10 megatons of

TNT

per second. However, the large power output of the Sun is mainly due to

the huge size and density of its core (compared to earth and objects on

earth), with only a fairly small amount of power being generated per

cubic metre. Theoretical models of the Sun's interior indicate a power density, or energy production, of approximately 276.5

watts per cubic metre,

[86] which is about the same rate of power production as takes place in

reptile metabolism or a

compost pile.

[87][e]

The fusion rate in the core is in a self-correcting equilibrium: a

slightly higher rate of fusion would cause the core to heat up more and

expand slightly against the weight of the outer layers, reducing the density and hence the fusion rate and correcting the

perturbation;

and a slightly lower rate would cause the core to cool and shrink

slightly, increasing the density and increasing the fusion rate and

again reverting it to its present rate.

[88][89]

Radiative zone

From the core out to about 0.7 solar radii,

thermal radiation is the primary means of energy transfer.

[90] The temperature drops from approximately 7 million to 2 million kelvins with increasing distance from the core.

[80] This

temperature gradient is less than the value of the

adiabatic lapse rate and hence cannot drive convection, which explains why the transfer of energy through this zone is by

radiation instead of thermal

convection.

[80] Ions of

hydrogen and

helium emit

photons, which travel only a brief distance before being reabsorbed by other ions.

[90] The density drops a hundredfold (from 20 g/cm

3 to 0.2 g/cm

3) from 0.25 solar radii to the 0.7 radii, the top of the radiative zone.

[90]

Tachocline

The radiative zone and the convective zone are separated by a transition layer, the

tachocline.

This is a region where the sharp regime change between the uniform

rotation of the radiative zone and the differential rotation of the

convection zone results in a large

shear between the two—a condition where successive horizontal layers slide past one another.

[91] Presently, it is hypothesized that a magnetic dynamo within this layer generates the Sun's

magnetic field.

[80]

Convective zone

The Sun's convection zone extends from 0.7 solar radii (500,000 km)

to near the surface. In this layer, the solar plasma is not dense enough

or hot enough to transfer the heat energy of the interior outward via

radiation. Instead, the density of the plasma is low enough to allow

convective currents to develop and move the Sun's energy outward towards

its surface. Material heated at the tachocline picks up heat and

expands, thereby reducing its density and allowing it to rise. As a

result, an orderly motion of the mass develops into

thermal cells

that carry the majority of the heat outward to the Sun's photosphere

above. Once the material diffusively and radiatively cools just beneath

the photospheric surface, its density increases, and it sinks to the

base of the convection zone, where it again picks up heat from the top

of the radiative zone and the convective cycle continues. At the

photosphere, the temperature has dropped to 5,700 K and the density to

only 0.2 g/m

3 (about 1/6,000 the density of air at sea level).

[80]

The thermal columns of the convection zone form an imprint on the

surface of the Sun giving it a granular appearance called the

solar granulation at the smallest scale and

supergranulation

at larger scales. Turbulent convection in this outer part of the solar

interior sustains "small-scale" dynamo action over the near-surface

volume of the Sun.

[80] The Sun's thermal columns are

Bénard cells and take the shape of hexagonal prisms.

[92]

Photosphere

The

effective temperature, or

black body

temperature, of the Sun (5,777 K) is the temperature a black body of

the same size must have to yield the same total emissive power.

The visible surface of the Sun, the photosphere, is the layer below which the Sun becomes

opaque to visible light.

[93]

Above the photosphere visible sunlight is free to propagate into space,

and almost all of its energy escapes the Sun entirely. The change in

opacity is due to the decreasing amount of

H− ions, which absorb visible light easily.

[93] Conversely, the visible light we see is produced as electrons react with

hydrogen atoms to produce H

− ions.

[94][95]

The photosphere is tens to hundreds of kilometers thick, and is slightly

less opaque than air on Earth. Because the upper part of the

photosphere is cooler than the lower part, an image of the Sun appears

brighter in the center than on the edge or

limb of the solar disk, in a phenomenon known as

limb darkening.

[93] The spectrum of sunlight has approximately the spectrum of a

black-body radiating at about 6,000

K, interspersed with atomic

absorption lines from the tenuous layers above the photosphere. The photosphere has a particle density of ~10

23 m

−3 (about 0.37% of the particle number per volume of

Earth's atmosphere

at sea level). The photosphere is not fully ionized—the extent of

ionization is about 3%, leaving almost all of the hydrogen in atomic

form.

[96]

During early studies of the

optical spectrum of the photosphere, some absorption lines were found that did not correspond to any

chemical elements then known on Earth. In 1868,

Norman Lockyer hypothesized that these absorption lines were caused by a new element that he dubbed

helium, after the Greek Sun god

Helios. Twenty-five years later, helium was isolated on Earth.

[97]

Atmosphere

During a total

solar eclipse, the solar

corona can be seen with the naked eye, during the brief period of totality.

During a total

solar eclipse,

when the disk of the Sun is covered by that of the Moon, parts of the

Sun's surrounding atmosphere can be seen. It is composed of four

distinct parts: the

chromosphere, the

transition region, the

corona and the

heliosphere.

The coolest layer of the Sun is a temperature minimum region extending to about

500 km above the photosphere, and has a temperature of about

4,100 K.

[93] This part of the Sun is cool enough to allow the existence of simple molecules such as

carbon monoxide and water, which can be detected via their absorption spectra.

[98]

The chromosphere, transition region, and corona are much hotter than the surface of the Sun.

[93] The reason is not well understood, but evidence suggests that

Alfvén waves may have enough energy to heat the corona.

[99]

Above the temperature minimum layer is a layer about

2,000 km thick, dominated by a spectrum of emission and absorption lines.

[93] It is called the

chromosphere from the Greek root

chroma, meaning color, because the chromosphere is visible as a colored flash at the beginning and end of total

solar eclipses.

[90] The temperature of the chromosphere increases gradually with altitude, ranging up to around

20,000 K near the top.

[93] In the upper part of the chromosphere

helium becomes partially

ionized.

[100]

Taken by

Hinode's

Solar Optical Telescope on 12 January 2007, this image of the Sun

reveals the filamentary nature of the plasma connecting regions of

different magnetic polarity.

Above the chromosphere, in a thin (about 200 km)

transition region, the temperature rises rapidly from around 20,000

K in the upper chromosphere to coronal temperatures closer to 1,000,000

K.

[101]

The temperature increase is facilitated by the full ionization of

helium in the transition region, which significantly reduces radiative

cooling of the plasma.

[100] The transition region does not occur at a well-defined altitude. Rather, it forms a kind of

nimbus around chromospheric features such as

spicules and

filaments, and is in constant, chaotic motion.

[90] The transition region is not easily visible from Earth's surface, but is readily observable from

space by instruments sensitive to the

extreme ultraviolet portion of the

spectrum.

[102]

The

corona is the next layer of the Sun. The low corona, near the surface of the Sun, has a particle density around 10

15 m

−3 to 10

16 m

−3.

[100][f]

The average temperature of the corona and solar wind is about

1,000,000–2,000,000 K; however, in the hottest regions it is

8,000,000–20,000,000 K.

[101] Although no complete theory yet exists to account for the temperature

of the corona, at least some of its heat is known to be from

magnetic reconnection.

[101][103]

The corona is the extended atmosphere of the Sun, which has a volume

much larger than the volume enclosed by the Sun's photosphere. A flow of

plasma outward from the Sun into interplanetary space is the

solar wind.

[103]

The

heliosphere,

the tenuous outermost atmosphere of the Sun, is filled with the solar

wind plasma. This outermost layer of the Sun is defined to begin at the

distance where the flow of the

solar wind becomes

superalfvénic—that is, where the flow becomes faster than the speed of

Alfvén waves,

[104]

at approximately 20 solar radii (0.1 AU).

Turbulence and dynamic forces in the heliosphere cannot affect the shape

of the solar corona within, because the information can only travel at

the speed of Alfvén waves. The solar wind travels outward continuously

through the heliosphere,

[105][106] forming the solar magnetic field into a

spiral shape,

[103] until it impacts the

heliopause more than 50

AU from the Sun. In December 2004, the

Voyager 1 probe passed through a shock front that is thought to be part of the heliopause.

[107] In late 2012 Voyager 1 recorded a marked increase in

cosmic ray

collisions and a sharp drop in lower energy particles from the solar

wind, which suggested that the probe had passed through the heliopause

and entered the

interstellar medium.

[108]

Photons and neutrinos

High-energy

gamma-ray

photons initially released with fusion reactions in the core are almost

immediately absorbed by the solar plasma of the radiative zone, usually

after traveling only a few millimeters. Re-emission happens in a random

direction and usually at a slightly lower energy. With this sequence of

emissions and absorptions, it takes a long time for radiation to reach

the Sun's surface. Estimates of the photon travel time range between

10,000 and 170,000 years.

[109] In contrast, it takes only 2.3 seconds for the

neutrinos,

which account for about 2% of the total energy production of the Sun,

to reach the surface. Because energy transport in the Sun is a process

that involves photons in thermodynamic equilibrium with matter, the time

scale of energy transport in the Sun is longer, on the order of

30,000,000 years. This is the time it would take the Sun to return to a

stable state, if the rate of energy generation in its core were suddenly

changed.

[110]

Neutrinos are also released by the fusion reactions in the core,

but, unlike photons, they rarely interact with matter, so almost all are

able to escape the Sun immediately. For many years measurements of the

number of neutrinos produced in the Sun were

lower than theories predicted by a factor of 3. This discrepancy was resolved in 2001 through the discovery of the effects of

neutrino oscillation: the Sun emits the number of neutrinos predicted by the

theory, but neutrino detectors were missing

2⁄3 of them because the neutrinos had changed

flavor by the time they were detected.

[111]

Magnetism and activity

Magnetic field

Visible light photograph of sunspot, 13 December 2006

In

this false-color ultraviolet image, the Sun shows a C3-class solar

flare (white area on upper left), a solar tsunami (wave-like structure,

upper right) and multiple filaments of

plasma following a magnetic field, rising from the stellar surface.

The Sun has a

magnetic field that varies across the surface of the Sun. Its polar field is 1–2

gauss (0.0001–0.0002

T), whereas the field is typically 3,000 gauss (0.3 T) in features on the Sun called

sunspots and 10–100 gauss (0.001–0.01 T) in

solar prominences.

[1]

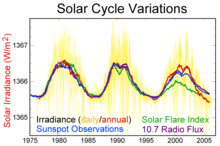

The magnetic field also varies in time and location. The quasi-periodic 11-year

solar cycle is the most prominent variation in which the number and size of sunspots waxes and wanes.

Sunspots are visible as dark patches on the Sun's

photosphere, and correspond to concentrations of magnetic field where the

convective transport

of heat is inhibited from the solar interior to the surface. As a

result, sunspots are slightly cooler than the surrounding photosphere,

and, so, they appear dark. At a typical

solar minimum,

few sunspots are visible, and occasionally none can be seen at all.

Those that do appear are at high solar latitudes. As the solar cycle

progresses towards its

maximum, sunspots tend form closer to the solar equator, a phenomenon known as

Spörer's law. The largest sunspots can be tens of thousands of kilometers across.

[115]

An 11-year sunspot cycle is half of a 22-year

Babcock–Leighton

dynamo cycle, which corresponds to an oscillatory exchange of energy between

toroidal and poloidal solar magnetic fields. At

solar-cycle maximum, the external poloidal dipolar magnetic field is near its dynamo-cycle minimum strength, but an internal

toroidal

quadrupolar field, generated through differential rotation within the

tachocline, is near its maximum strength. At this point in the dynamo

cycle, buoyant upwelling within the convective zone forces emergence of

toroidal magnetic field through the photosphere, giving rise to pairs of

sunspots, roughly aligned east–west and having footprints with opposite

magnetic polarities. The magnetic polarity of sunspot pairs alternates

every solar cycle, a phenomenon known as the Hale cycle.

[116][117]

During the solar cycle's declining phase, energy shifts from the

internal toroidal magnetic field to the external poloidal field, and

sunspots diminish in number and size. At

solar-cycle minimum,

the toroidal field is, correspondingly, at minimum strength, sunspots

are relatively rare, and the poloidal field is at its maximum strength.

With the rise of the next 11-year sunspot cycle, differential rotation

shifts magnetic energy back from the poloidal to the toroidal field, but

with a polarity that is opposite to the previous cycle. The process

carries on continuously, and in an idealized, simplified scenario, each

11-year sunspot cycle corresponds to a change, then, in the overall

polarity of the Sun's large-scale magnetic field.

[118][119]

The solar magnetic field extends well beyond the Sun itself. The

electrically conducting solar wind plasma carries the Sun's magnetic

field into space, forming what is called the

interplanetary magnetic field.

[103] In an approximation known as ideal

magnetohydrodynamics,

plasma particles only move along the magnetic field lines. As a result,

the outward-flowing solar wind stretches the interplanetary magnetic

field outward, forcing it into a roughly radial structure. For a simple

dipolar solar magnetic field, with opposite hemispherical polarities on

either side of the solar magnetic equator, a thin

current sheet is formed in the solar wind.

[103] At great distances, the rotation of the Sun twists the dipolar magnetic field and corresponding current sheet into an

Archimedean spiral structure called the

Parker spiral.

[103]

The interplanetary magnetic field is much stronger than the dipole

component of the solar magnetic field. The Sun's dipole magnetic field

of 50–400

μT

(at the photosphere) reduces with the inverse-cube of the distance to

about 0.1 nT at the distance of Earth. However, according to spacecraft

observations the interplanetary field at Earth's location is around

5 nT, about a hundred times greater.

[120] The difference is due to magnetic fields generated by electrical currents in the plasma surrounding the Sun.

Variation in activity

Measurements from 2005 of solar cycle variation during the last 30 years

The Sun's magnetic field leads to many effects that are collectively called

solar activity.

Solar flares and

coronal-mass ejections tend to occur at sunspot groups. Slowly changing high-speed streams of

solar wind are emitted from

coronal holes at the photospheric surface. Both coronal-mass ejections and high-speed streams of solar wind carry plasma and

interplanetary magnetic field outward into the Solar System.

[121] The effects of solar activity on Earth include

auroras at moderate to high latitudes and the disruption of radio communications and

electric power. Solar activity is thought to have played a large role in the

formation and evolution of the Solar System.

With solar-cycle modulation of sunspot number comes a corresponding modulation of

space weather conditions, including those surrounding Earth where technological systems can be affected.

Long-term change

Long-term secular change in sunspot number is thought, by some

scientists, to be correlated with long-term change in solar irradiance,

[122] which, in turn, might influence Earth's long-term climate.

[123]

For example, in the 17th century, the solar cycle appeared to have

stopped entirely for several decades; few sunspots were observed during a

period known as the

Maunder minimum. This coincided in time with the era of the

Little Ice Age, when Europe experienced unusually cold temperatures.

[124] Earlier extended minima have been discovered through analysis of

tree rings and appear to have coincided with lower-than-average global temperatures.

[125]

A recent theory claims that there are magnetic instabilities in

the core of the Sun that cause fluctuations with periods of either

41,000 or 100,000 years. These could provide a better explanation of the

ice ages than the

Milankovitch cycles.

[126][127]

Life phases

The Sun today is roughly halfway through the most stable part of its life. It has not changed dramatically for over four billion

[a]

years, and will remain fairly stable for more than five billion more.

However, after hydrogen fusion in its core has stopped, the Sun will

undergo dramatic changes, both internally and externally.

Formation

The Sun formed about 4.6 billion years ago from the collapse of part of a giant

molecular cloud that consisted mostly of hydrogen and helium and that probably gave birth to many other stars.

[128] This age is estimated using

computer models of

stellar evolution and through

nucleocosmochronology.

[10] The result is consistent with the

radiometric date of the oldest Solar System material, at 4.567 billion years ago.

[129][130] Studies of ancient

meteorites reveal traces of stable daughter nuclei of short-lived isotopes, such as

iron-60,

that form only in exploding, short-lived stars. This indicates that one

or more supernovae must have occurred near the location where the Sun

formed. A

shock wave

from a nearby supernova would have triggered the formation of the Sun

by compressing the matter within the molecular cloud and causing certain

regions to collapse under their own gravity.

[131] As one fragment of the cloud collapsed it also began to rotate because of

conservation of angular momentum

and heat up with the increasing pressure. Much of the mass became

concentrated in the center, whereas the rest flattened out into a disk

that would become the planets and other Solar System bodies. Gravity and

pressure within the core of the cloud generated a lot of heat as it

accreted more matter from the surrounding disk, eventually triggering

nuclear fusion. Thus, the Sun was born.

Main sequence

The Sun is about halfway through its

main-sequence stage, during which nuclear fusion reactions in its core fuse hydrogen into helium. Each second, more than four million

tonnes of matter are converted into energy within the Sun's core, producing

neutrinos and

solar radiation.

At this rate, the Sun has so far converted around 100 times the mass of

Earth into energy, about 0.03% of the total mass of the Sun. The Sun

will spend a total of approximately 10

billion years as a main-sequence star.

[133]

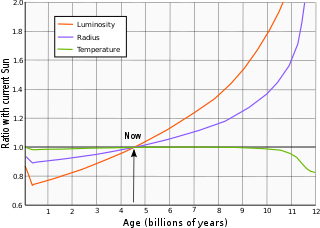

The Sun is gradually becoming hotter during its time on the main

sequence, because the helium atoms in the core occupy less volume than

the

hydrogen atoms

that were fused. The core is therefore shrinking, allowing the outer

layers of the Sun to move closer to the centre and experience a stronger

gravitational force, according to the

inverse-square law.

This stronger force increases the pressure on the core, which is

resisted by a gradual increase in the rate at which fusion occurs. This

process speeds up as the core gradually becomes denser. It is estimated

that the Sun has become 30% brighter in the last 4.5 billion years.

[134] At present, it is increasing in brightness by about 1% every 100 million years.

[135]

After core hydrogen exhaustion

The size of the current Sun (now in the

main sequence) compared to its estimated size during its red-giant phase in the future

The Sun does not have enough mass to explode as a

supernova. Instead it will exit the

main sequence in approximately 5 billion years and start to turn into a

red giant.

[136][137] As a red giant, the Sun will grow so large that it will engulf Mercury, Venus, and probably Earth.

[137][138]

Even before it becomes a red giant, the luminosity of the Sun

will have nearly doubled, and Earth will receive as much sunlight as

Venus receives today. Once the core hydrogen is exhausted in 5.4 billion

years, the Sun will expand into a

subgiant

phase and slowly double in size over about half a billion years. It

will then expand more rapidly over about half a billion years until it

is over two hundred times larger than today and a couple of thousand

times more luminous. This then starts the

red-giant-branch phase where the Sun will spend around a billion years and lose around a third of its mass.

[137]

Evolution of a Sun-like star. The track of a one solar mass star on the

Hertzsprung–Russell diagram is shown from the main sequence to the post-asymptotic-giant-branch stage.

After the red-giant branch the Sun has approximately 120 million

years of active life left, but much happens. First, the core, full of

degenerate helium ignites violently in the

helium flash,

where it is estimated that 6% of the core, itself 40% of the Sun's

mass, will be converted into carbon within a matter of minutes through

the

triple-alpha process.

[139]

The Sun then shrinks to around 10 times its current size and 50 times

the luminosity, with a temperature a little lower than today. It will

then have reached the

red clump or

horizontal branch,

but a star of the Sun's mass does not evolve blueward along the

horizontal branch. Instead, it just becomes moderately larger and more

luminous over about 100 million years as it continues to burn helium in

the core.

[137]

When the helium is exhausted, the Sun will repeat the expansion

it followed when the hydrogen in the core was exhausted, except that

this time it all happens faster, and the Sun becomes larger and more

luminous. This is the

asymptotic-giant-branch

phase, and the Sun is alternately burning hydrogen in a shell or helium

in a deeper shell. After about 20 million years on the early asymptotic

giant branch, the Sun becomes increasingly unstable, with rapid mass

loss and

thermal pulses

that increase the size and luminosity for a few hundred years every

100,000 years or so. The thermal pulses become larger each time, with

the later pulses pushing the luminosity to as much as 5,000 times the

current level and the radius to over 1 AU.

[140] According to a 2008 model, Earth's orbit is shrinking due to

tidal forces (and, eventually, drag from the lower

chromosphere),

so that it will be engulfed by the Sun near the tip of the red giant

branch phase, 1 and 3.8 million years after Mercury and Venus have

respectively suffered the same fate. Models vary depending on the rate

and timing of mass loss. Models that have higher mass loss on the

red-giant branch produce smaller, less luminous stars at the tip of the

asymptotic giant branch, perhaps only 2,000 times the luminosity and

less than 200 times the radius.

[137] For the Sun, four thermal pulses are predicted before it completely loses its outer envelope and starts to make a

planetary nebula. By the end of that phase—lasting approximately 500,000 years—the Sun will only have about half of its current mass.

The post-asymptotic-giant-branch evolution is even faster. The

luminosity stays approximately constant as the temperature increases,

with the ejected half of the Sun's mass becoming ionised into a

planetary nebula as the exposed core reaches 30,000 K. The final naked core, a

white dwarf, will have a temperature of over 100,000 K, and contain an estimated 54.05% of the Sun's present day mass.

[137]

The planetary nebula will disperse in about 10,000 years, but the white

dwarf will survive for trillions of years before fading to a

hypothetical

black dwarf.

[141][142]

Motion and location

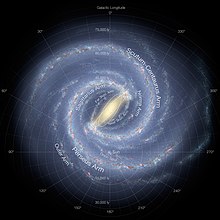

Illustration of the Milky Way, showing the location of the Sun

The Sun lies close to the inner rim of the

Milky Way's

Orion Arm, in the

Local Interstellar Cloud or the

Gould Belt, at a distance of 7.5–8.5

kpc (25,000–28,000 light-years) from the

Galactic Center. The Sun is contained within the

Local Bubble, a space of rarefied hot gas, possibly produced by the supernova remnant

Geminga,

[149] or multiple supernovae in subgroup B1 of the Pleiades moving group.

[150] The distance between the local arm and the next arm out, the

Perseus Arm, is about 6,500 light-years.

[151] The Sun, and thus the Solar System, is found in what scientists call the

galactic habitable zone.

The

Apex of the Sun's Way, or the

solar apex, is the direction that the Sun travels relative to other nearby stars. This motion is towards a point in the constellation

Hercules, near the star

Vega. Of the 50

nearest stellar systems within 17 light-years from Earth (the closest being the red dwarf

Proxima Centauri at approximately 4.2 light-years), the Sun ranks fourth in mass.

[152]

Orbit in Milky Way

The Sun orbits the center of the Milky Way, and it is presently moving in the direction of the constellation of

Cygnus. A simple model of the motion of a star in the galaxy gives the

galactic coordinates X,

Y, and

Z as:

where

U,

V, and

W are the respective velocities with respect to the

local standard of rest,

A and

B are the

Oort constants,

is the angular velocity of galactic rotation for the local standard of rest,

is the "epicyclic frequency", and ν is the vertical oscillation frequency.

[153] For the sun, the present values of

U,

V, and

W are estimated as

km/s, and estimates for the other constants are

A = 15.5 km/s/

kpc,

B = −12.2 km/s/kpc, κ = 37 km/s/kpc, and ν=74 km/s/kpc. We take

X(0) and

Y(0) to be zero and

Z(0) is estimated to be 17 parsecs.

[154]

This model implies that the sun circulates around a point that is

itself going around the galaxy. The period of the sun's circulation

around the point is

.

which, using the equivalence that a parsec equals 1 km/s times 0.978

million years, comes to 166 million years, shorter than the time it

takes for the point to go around the galaxy. In the (

X, Y) coordinates, the sun describes an ellipse around the point, whose length in the

Y direction is

and whose width in the

X direction is

The ratio of length to width of this ellipse, the same for all stars in our neighborhood, is

The moving point is presently at

The oscillation in the

Z direction takes the sun

above the galactic plane and the same distance below it, with a period of

or 83 million years, approximately 2.7 times per orbit.

[155] Although

is 222 million years, the value of

at the point around which the sun circulates is

(see

Oort constants),

corresponding to 235 million years, and this is the time that the point

takes to go once around the galaxy. Other stars with the same value of

have take the same amount of time to go around the galaxy as the sun and thus remain in the same general vicinity as the sun.

The Sun's orbit around the Milky Way is perturbed due to the

non-uniform mass distribution in Milky Way, such as that in and between

the galactic spiral arms. It has been argued that the Sun's passage

through the higher density spiral arms often coincides with

mass extinctions on Earth, perhaps due to increased

impact events.

[156] It takes the Solar System about 225–250 million years to complete one orbit through the Milky Way (a

galactic year),

[157] so it is thought to have completed 20–25 orbits during the lifetime of the Sun. The

orbital speed of the Solar System about the center of the Milky Way is approximately 251 km/s (156 mi/s).

[158] At this speed, it takes around 1,190 years for the Solar System to travel a distance of 1 light-year, or 7 days to travel 1

AU.

[159]

The Milky Way is moving with respect to the

cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) in the direction of the constellation

Hydra with a speed of 550 km/s, and the Sun's resultant velocity with respect to the CMB is about 370 km/s in the direction of

Crater or

Leo.

[160]

Theoretical problems

Map of the full Sun by STEREO and

SDO spacecraft

Coronal heating problem

The temperature of the photosphere is approximately 6,000 K, whereas

the temperature of the corona reaches 1,000,000–2,000,000 K.

[101] The high temperature of the corona shows that it is heated by something other than direct

heat conduction from the photosphere.

[103]

It is thought that the energy necessary to heat the corona is

provided by turbulent motion in the convection zone below the

photosphere, and two main mechanisms have been proposed to explain

coronal heating.

[101] The first is

wave heating, in which sound, gravitational or magnetohydrodynamic waves are produced by turbulence in the convection zone.

[101] These waves travel upward and dissipate in the corona, depositing their energy in the ambient matter in the form of heat.

[161] The other is

magnetic heating, in which magnetic energy is continuously built up by photospheric motion and released through

magnetic reconnection in the form of large

solar flares and myriad similar but smaller events—

nanoflares.

[162]

Currently, it is unclear whether waves are an efficient heating mechanism. All waves except

Alfvén waves have been found to dissipate or refract before reaching the corona.

[163]

In addition, Alfvén waves do not easily dissipate in the corona.

Current research focus has therefore shifted towards flare heating

mechanisms.

[101]

Faint young Sun problem

Theoretical models of the Sun's development suggest that 3.8 to 2.5 billion years ago, during the

Archean eon,

the Sun was only about 75% as bright as it is today. Such a weak star

would not have been able to sustain liquid water on Earth's surface, and

thus life should not have been able to develop. However, the geological

record demonstrates that Earth has remained at a fairly constant

temperature throughout its history, and that the young Earth was

somewhat warmer than it is today. One theory among scientists is that

the atmosphere of the young Earth contained much larger quantities of

greenhouse gases (such as

carbon dioxide,

methane) than are present today, which trapped enough heat to compensate for the smaller amount of

solar energy reaching it.

[164]

However, examination of Archaean sediments appears inconsistent

with the hypothesis of high greenhouse concentrations. Instead, the

moderate temperature range may be explained by a lower surface

albedo

brought about by less continental area and the "lack of biologically

induced cloud condensation nuclei". This would have led to increased

absorption of solar energy, thereby compensating for the lower solar

output.

[165]

History of observation

The enormous effect of the Sun on Earth has been recognized since

prehistoric times, and the Sun has been

regarded by some cultures as a

deity.

Early understanding

The Sun has been an object of veneration in many cultures throughout

human history. Humanity's most fundamental understanding of the Sun is

as the luminous disk in the

sky, whose presence above the

horizon creates day and whose absence causes night. In many prehistoric and ancient cultures, the Sun was thought to be a

solar deity or other

supernatural entity.

Worship of the Sun was central to civilizations such as the

ancient Egyptians, the

Inca of South America and the

Aztecs of what is now

Mexico. In religions such as

Hinduism, the Sun is still considered a god. Many ancient monuments were constructed with solar phenomena in mind; for example, stone

megaliths accurately mark the summer or winter

solstice (some of the most prominent megaliths are located in

Nabta Playa,

Egypt;

Mnajdra, Malta and at

Stonehenge, England);

Newgrange, a prehistoric human-built mount in Ireland, was designed to detect the winter solstice; the pyramid of

El Castillo at

Chichén Itzá in Mexico is designed to cast shadows in the shape of serpents climbing the

pyramid at the vernal and autumnal

equinoxes.

The Egyptians portrayed the god

Ra as being carried across the sky in a solar barque, accompanied by lesser gods, and to the Greeks, he was

Helios, carried by a chariot drawn by fiery horses. From the reign of

Elagabalus in the

late Roman Empire the Sun's birthday was a holiday celebrated as

Sol Invictus (literally "Unconquered Sun") soon after the winter solstice, which may have been an antecedent to Christmas. Regarding the

fixed stars, the Sun appears from Earth to revolve once a year along the

ecliptic through the

zodiac, and so Greek astronomers categorized it as one of the seven

planets (Greek

planetes, "wanderer"); the naming of the

days of the weeks after the seven planets dates to the

Roman era.

[166][167][168]

Development of scientific understanding

In the early first millennium BC,

Babylonian astronomers

observed that the Sun's motion along the ecliptic is not uniform,

though they did not know why; it is today known that this is due to the

movement of

Earth in an

elliptic orbit around the Sun, with Earth moving faster when it is nearer to the Sun at

perihelion and moving slower when it is farther away at

aphelion.

[169]

One of the first people to offer a scientific or philosophical explanation for the Sun was the

Greek philosopher Anaxagoras. He reasoned that it was not the

chariot of

Helios, but instead a giant flaming ball of metal even larger than the land of the

Peloponnesus and that the

Moon reflected the light of the Sun.

[170] For teaching this

heresy, he was imprisoned by the authorities and

sentenced to death, though he was later released through the intervention of

Pericles.

Eratosthenes estimated the distance between Earth and the Sun in the 3rd century BC as "of stadia

myriads 400 and 80000", the translation of which is ambiguous, implying either 4,080,000

stadia

(755,000 km) or 804,000,000 stadia (148 to 153 million kilometers or

0.99 to 1.02 AU); the latter value is correct to within a few percent.

In the 1st century AD,

Ptolemy estimated the distance as 1,210 times

the radius of Earth, approximately 7.71 million kilometers (0.0515 AU).

[171]

The theory that the Sun is the center around which the planets orbit was first proposed by the ancient Greek

Aristarchus of Samos in the 3rd century BC, and later adopted by

Seleucus of Seleucia (see

Heliocentrism). This view was developed in a more detailed

mathematical model of a heliocentric system in the 16th century by

Nicolaus Copernicus.

Observations of sunspots were recorded during the

Han Dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) by

Chinese astronomers, who maintained records of these observations for centuries.

Averroes also provided a description of sunspots in the 12th century.

[172] The invention of the

telescope in the early 17th century permitted detailed observations of

sunspots by

Thomas Harriot,

Galileo Galilei

and other astronomers. Galileo posited that sunspots were on the

surface of the Sun rather than small objects passing between Earth and

the Sun.

[173]

Arabic astronomical contributions include

Albatenius' discovery that the direction of the Sun's

apogee (the place in the Sun's orbit against the fixed stars where it seems to be moving slowest) is changing.

[174] (In modern heliocentric terms, this is caused by a gradual motion of the aphelion of the

Earth's orbit).

Ibn Yunus observed more than 10,000 entries for the Sun's position for many years using a large

astrolabe.

[175]

Sol, the Sun, from a 1550 edition of

Guido Bonatti's

Liber astronomiae.

From an observation of a

transit of Venus in 1032, the Persian astronomer and polymath

Avicenna concluded that Venus is closer to Earth than the Sun.

[176] In 1672

Giovanni Cassini and

Jean Richer determined the distance to

Mars and were thereby able to calculate the distance to the Sun.

In 1666,

Isaac Newton observed the Sun's light using a

prism, and showed that it is made up of light of many colors.

[177] In 1800,

William Herschel discovered

infrared radiation beyond the red part of the solar spectrum.

[178] The 19th century saw advancement in spectroscopic studies of the Sun;

Joseph von Fraunhofer recorded more than 600

absorption lines in the spectrum, the strongest of which are still often referred to as

Fraunhofer lines. In the early years of the modern scientific era, the source of the Sun's energy was a significant puzzle.

Lord Kelvin suggested that the Sun is a gradually cooling liquid body that is radiating an internal store of heat.

[179] Kelvin and

Hermann von Helmholtz then proposed a

gravitational contraction

mechanism to explain the energy output, but the resulting age estimate

was only 20 million years, well short of the time span of at least 300

million years suggested by some geological discoveries of that time.

[179][180] In 1890

Joseph Lockyer, who discovered helium in the solar spectrum, proposed a meteoritic hypothesis for the formation and evolution of the Sun.

[181]

Not until 1904 was a documented solution offered.

Ernest Rutherford suggested that the Sun's output could be maintained by an internal source of heat, and suggested

radioactive decay as the source.

[182] However, it would be

Albert Einstein who would provide the essential clue to the source of the Sun's energy output with his

mass-energy equivalence relation

E = mc2.

[183] In 1920, Sir

Arthur Eddington

proposed that the pressures and temperatures at the core of the Sun

could produce a nuclear fusion reaction that merged hydrogen (protons)

into helium nuclei, resulting in a production of energy from the net

change in mass.

[184] The preponderance of hydrogen in the Sun was confirmed in 1925 by

Cecilia Payne using the

ionization theory developed by

Meghnad Saha, an Indian physicist. The theoretical concept of fusion was developed in the 1930s by the astrophysicists

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and

Hans Bethe. Hans Bethe calculated the details of the two main energy-producing nuclear reactions that power the Sun.

[185][186] In 1957,

Margaret Burbidge,

Geoffrey Burbidge,

William Fowler and

Fred Hoyle showed that most of the elements in the universe have been

synthesized by nuclear reactions inside stars, some like the Sun.

[187]

Solar space missions

A lunar transit of the Sun captured during calibration of STEREO B's ultraviolet imaging cameras

[188]

The first satellites designed to observe the Sun were

NASA's

Pioneers

5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, which were launched between 1959 and 1968. These

probes orbited the Sun at a distance similar to that of Earth, and made

the first detailed measurements of the solar wind and the solar magnetic

field.

Pioneer 9 operated for a particularly long time, transmitting data until May 1983.

[189][190]

In the 1970s, two

Helios spacecraft and the

Skylab Apollo Telescope Mount

provided scientists with significant new data on solar wind and the

solar corona. The Helios 1 and 2 probes were U.S.–German collaborations

that studied the solar wind from an orbit carrying the spacecraft inside

Mercury's orbit at

perihelion.

[191] The Skylab space station, launched by NASA in 1973, included a solar

observatory module called the Apollo Telescope Mount that was operated by astronauts resident on the station.

[102]

Skylab made the first time-resolved observations of the solar

transition region and of ultraviolet emissions from the solar corona.

[102] Discoveries included the first observations of

coronal mass ejections, then called "coronal transients", and of

coronal holes, now known to be intimately associated with the

solar wind.

[191]

In 1980, the

Solar Maximum Mission was launched by

NASA. This spacecraft was designed to observe

gamma rays,

X-rays and

UV radiation from

solar flares during a time of high solar activity and

solar luminosity.

Just a few months after launch, however, an electronics failure caused

the probe to go into standby mode, and it spent the next three years in

this inactive state. In 1984

Space Shuttle Challenger mission

STS-41C

retrieved the satellite and repaired its electronics before

re-releasing it into orbit. The Solar Maximum Mission subsequently

acquired thousands of images of the solar corona before

re-entering Earth's atmosphere in June 1989.

[192]

Launched in 1991, Japan's

Yohkoh (

Sunbeam)

satellite observed solar flares at X-ray wavelengths. Mission data

allowed scientists to identify several different types of flares, and

demonstrated that the corona away from regions of peak activity was much

more dynamic and active than had previously been supposed. Yohkoh

observed an entire solar cycle but went into standby mode when an

annular eclipse in 2001 caused it to lose its lock on the Sun. It was destroyed by atmospheric re-entry in 2005.

[193]

One of the most important solar missions to date has been the

Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, jointly built by the

European Space Agency and

NASA and launched on 2 December 1995.

[102] Originally intended to serve a two-year mission, a mission extension through 2012 was approved in October 2009.

[194] It has proven so useful that a follow-on mission, the

Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), was launched in February 2010.

[195] Situated at the

Lagrangian point

between Earth and the Sun (at which the gravitational pull from both is

equal), SOHO has provided a constant view of the Sun at many

wavelengths since its launch.

[102] Besides its direct solar observation, SOHO has enabled the discovery of a large number of

comets, mostly tiny

sungrazing comets that incinerate as they pass the Sun.

[196]

A solar prominence erupts in August 2012, as captured by SDO

All these satellites have observed the Sun from the plane of the

ecliptic, and so have only observed its equatorial regions in detail.

The

Ulysses probe was launched in 1990 to study the Sun's polar regions. It first travelled to

Jupiter,

to "slingshot" into an orbit that would take it far above the plane of

the ecliptic. Once Ulysses was in its scheduled orbit, it began

observing the solar wind and magnetic field strength at high solar

latitudes, finding that the solar wind from high latitudes was moving at

about 750 km/s, which was slower than expected, and that there were

large magnetic waves emerging from high latitudes that scattered

galactic

cosmic rays.

[197]

Elemental abundances in the photosphere are well known from

spectroscopic studies, but the composition of the interior of the Sun is more poorly understood. A

solar wind sample return mission,

Genesis, was designed to allow astronomers to directly measure the composition of solar material.

[198]

The

Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory

(STEREO) mission was launched in October 2006. Two identical spacecraft

were launched into orbits that cause them to (respectively) pull

further ahead of and fall gradually behind Earth. This enables

stereoscopic imaging of the Sun and solar phenomena, such as

coronal mass ejections.

[199][200]

The

Indian Space Research Organisation has scheduled the launch of a 100 kg satellite named

Aditya for 2017–18. Its main instrument will be a

coronagraph for studying the dynamics of the Solar corona.

[201]

Observation and effects

During

certain atmospheric conditions, the Sun becomes clearly visible to the

naked eye, and can be observed without stress to the eyes. Click on this

photo to see the full cycle of a

sunset, as observed from the high plains of the

Mojave Desert.

The Sun, as seen from low Earth orbit overlooking the

International Space Station. This sunlight is not filtered by the lower atmosphere, which blocks much of the solar spectrum

The brightness of the Sun can cause pain from looking at it with the

naked eye; however, doing so for brief periods is not hazardous for normal non-dilated eyes.

[202][203] Looking directly at the Sun causes

phosphene

visual artifacts and temporary partial blindness. It also delivers

about 4 milliwatts of sunlight to the retina, slightly heating it and

potentially causing damage in eyes that cannot respond properly to the

brightness.

[204][205] UV exposure gradually yellows the lens of the eye over a period of years, and is thought to contribute to the formation of

cataracts, but this depends on general exposure to solar UV, and not whether one looks directly at the Sun.

[206]

Long-duration viewing of the direct Sun with the naked eye can begin to

cause UV-induced, sunburn-like lesions on the retina after about 100

seconds, particularly under conditions where the UV light from the Sun

is intense and well focused;

[207][208]

conditions are worsened by young eyes or new lens implants (which admit

more UV than aging natural eyes), Sun angles near the zenith, and

observing locations at high altitude.

Viewing the Sun through light-concentrating

optics such as

binoculars

may result in permanent damage to the retina without an appropriate

filter that blocks UV and substantially dims the sunlight. When using an

attenuating filter to view the Sun, the viewer is cautioned to use a

filter specifically designed for that use. Some improvised filters that

pass UV or

IR rays, can actually harm the eye at high brightness levels.

[209]

Herschel wedges,

also called Solar Diagonals, are effective and inexpensive for small

telescopes. The sunlight that is destined for the eyepiece is reflected

from an unsilvered surface of a piece of glass. Only a very small

fraction of the incident light is reflected. The rest passes through the

glass and leaves the instrument. If the glass breaks because of the

heat, no light at all is reflected, making the device fail-safe. Simple

filters made of darkened glass allow the full intensity of sunlight to

pass through if they break, endangering the observer's eyesight.

Unfiltered binoculars can deliver hundreds of times as much energy as

using the naked eye, possibly causing immediate damage. It is claimed

that even brief glances at the midday Sun through an unfiltered

telescope can cause permanent damage.

[210]

Partial

solar eclipses are hazardous to view because the eye's

pupil

is not adapted to the unusually high visual contrast: the pupil dilates

according to the total amount of light in the field of view,

not by the brightest object in the field. During partial eclipses most sunlight is blocked by the

Moon passing in front of the Sun, but the uncovered parts of the photosphere have the same

surface brightness

as during a normal day. In the overall gloom, the pupil expands from

~2 mm to ~6 mm, and each retinal cell exposed to the solar image

receives up to ten times more light than it would looking at the

non-eclipsed Sun. This can damage or kill those cells, resulting in

small permanent blind spots for the viewer.

[211]

The hazard is insidious for inexperienced observers and for children,

because there is no perception of pain: it is not immediately obvious

that one's vision is being destroyed.

During

sunrise and

sunset, sunlight is attenuated because of

Rayleigh scattering and

Mie scattering from a particularly long passage through Earth's atmosphere,

[212]

and the Sun is sometimes faint enough to be viewed comfortably with the

naked eye or safely with optics (provided there is no risk of bright

sunlight suddenly appearing through a break between clouds). Hazy

conditions, atmospheric dust, and high humidity contribute to this

atmospheric attenuation.

[213]

An

optical phenomenon, known as a

green flash,

can sometimes be seen shortly after sunset or before sunrise. The flash

is caused by light from the Sun just below the horizon being

bent (usually through a

temperature inversion)

towards the observer. Light of shorter wavelengths (violet, blue,

green) is bent more than that of longer wavelengths (yellow, orange,

red) but the violet and blue light is

scattered more, leaving light that is perceived as green.

[214]

Ultraviolet light from the Sun has

antiseptic properties and can be used to sanitize tools and water. It also causes

sunburn, and has other biological effects such as the production of

vitamin D and

sun tanning. Ultraviolet light is strongly attenuated by Earth's

ozone layer, so that the amount of UV varies greatly with

latitude and has been partially responsible for many biological adaptations, including variations in

human skin color in different regions of the globe.

[215]

Planetary system

The Sun has eight known planets. This includes four

terrestrial planets (

Mercury,

Venus,

Earth, and

Mars), two

gas giants (

Jupiter and

Saturn), and two

ice giants (

Uranus and

Neptune). The Solar System also has at least five

dwarf planets, an

asteroid belt, numerous

comets, and a large number of icy bodies which lie beyond the orbit of Neptune.