From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Photovoltaics (PV) is a method of converting solar energy into direct current electricity using semiconducting materials that exhibit the photovoltaic effect. A photovoltaic system employs solar panels composed of a number of solar cells to supply usable solar power. Power generation from solar PV has long been seen as a clean sustainable[1] energy technology which draws upon the planet’s most plentiful and widely distributed renewable energy source – the sun. The direct conversion of sunlight to electricity occurs without any moving parts or environmental emissions during operation. It is well proven, as photovoltaic systems have now been used for fifty years in specialized applications, and grid-connected PV systems have been in use for over twenty years.[2] They were first mass produced in the year 2000, when German environmentalists including Eurosolar succeeded in obtaining government support for the 100,000 roofs program.[3]

Driven by advances in technology and increases in manufacturing scale and sophistication, the cost of photovoltaics has declined steadily since the first solar cells were manufactured,[2][4] and the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) from PV is competitive with conventional electricity sources in an expanding list of geographic regions.[5] Net metering and financial incentives, such as preferential feed-in tariffs for solar-generated electricity, have supported solar PV installations in many countries.[6] With current technology, photovoltaics recoup the energy needed to manufacture them in 1.5 (in Southern Europe) to 2.5 years (in Northern Europe).[7]

Solar PV is now, after hydro and wind power, the third most important renewable energy source in terms of globally installed capacity. More than 100 countries use solar PV. Installations may be ground-mounted (and sometimes integrated with farming and grazing) or built into the roof or walls of a building (either building-integrated photovoltaics or simply rooftop).

In 2013, the fast-growing capacity of worldwide installed solar PV increased by 38 percent to 139 gigawatts (GW). This is sufficient to generate at least 160 terawatt-hours (TWh) or about 0.85 percent of the electricity demand on the planet. As of early 2015, worldwide installed solar PV has increased to 200 GW.[8] China, followed by Japan and the United States, is now the fastest growing market, while Germany remains the world's largest producer, contributing almost 6 percent to its national electricity demands.[9][10][11]

Etymology

The term "photovoltaic" comes from the Greek φῶς (phōs) meaning "light", and from "volt", the unit of electro-motive force, the volt, which in turn comes from the last name of the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, inventor of the battery (electrochemical cell). The term "photo-voltaic" has been in use in English since 1849.[12]Solar cells

Solar cells produce direct current electricity from sun light which can be used to power equipment or to recharge a battery. The first practical application of photovoltaics was to power orbiting satellites and other spacecraft, but today the majority of photovoltaic modules are used for grid connected power generation. In this case an inverter is required to convert the DC to AC. There is a smaller market for off-grid power for remote dwellings, boats, recreational vehicles, electric cars, roadside emergency telephones, remote sensing, and cathodic protection of pipelines.

Photovoltaic power generation employs solar panels composed of a number of solar cells containing a photovoltaic material. Materials presently used for photovoltaics include monocrystalline silicon, polycrystalline silicon, amorphous silicon, cadmium telluride, and copper indium gallium selenide/sulfide.[15] Copper solar cables connect modules (module cable), arrays (array cable), and sub-fields. Because of the growing demand for renewable energy sources, the manufacturing of solar cells and photovoltaic arrays has advanced considerably in recent years.[16][17][18]

Solar photovoltaics power generation has long been seen as a clean energy technology which draws upon the planet’s most plentiful and widely distributed renewable energy source – the sun. The technology is “inherently elegant” in that the direct conversion of sunlight to electricity occurs without any moving parts or environmental emissions during operation. It is well proven, as photovoltaic systems have now been used for fifty years in specialised applications, and grid-connected systems have been in use for over twenty years.

Cells require protection from the environment and are usually packaged tightly behind a glass sheet. When more power is required than a single cell can deliver, cells are electrically connected together to form photovoltaic modules, or solar panels. A single module is enough to power an emergency telephone, but for a house or a power plant the modules must be arranged in multiples as arrays.

Photovoltaic power capacity is measured as maximum power output under standardized test conditions (STC) in "Wp" (Watts peak).[19] The actual power output at a particular point in time may be less than or greater than this standardized, or "rated," value, depending on geographical location, time of day, weather conditions, and other factors.[20] Solar photovoltaic array capacity factors are typically under 25%, which is lower than many other industrial sources of electricity.[21]

Current developments

For best performance, terrestrial PV systems aim to maximize the time they face the sun. Solar trackers achieve this by moving PV panels to follow the sun. The increase can be by as much as 20% in winter and by as much as 50% in summer. Static mounted systems can be optimized by analysis of the sun path. Panels are often set to latitude tilt, an angle equal to the latitude, but performance can be improved by adjusting the angle for summer or winter. Generally, as with other semiconductor devices, temperatures above room temperature reduce the performance of photovoltaics.[22]A number of solar panels may also be mounted vertically above each other in a tower, if the zenith distance of the Sun is greater than zero, and the tower can be turned horizontally as a whole and each panels additionally around a horizontal axis. In such a tower the panels can follow the Sun exactly. Such a device may be described as a ladder mounted on a turnable disk. Each step of that ladder is the middle axis of a rectangular solar panel. In case the zenith distance of the Sun reaches zero, the "ladder" may be rotated to the north or the south to avoid a solar panel producing a shadow on a lower solar panel. Instead of an exactly vertical tower one can choose a tower with an axis directed to the polar star, meaning that it is parallel to the rotation axis of the Earth. In this case the angle between the axis and the Sun is always larger than 66 degrees. During a day it is only necessary to turn the panels around this axis to follow the Sun. Installations may be ground-mounted (and sometimes integrated with farming and grazing)[23] or built into the roof or walls of a building (building-integrated photovoltaics).

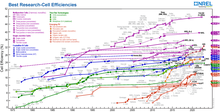

Efficiency

Although it is important to have an efficient solar cell, it is not necessarily the efficient solar cell that consumers will use. It is important to have efficient solar cells that are the best value for the money. Efficiency of pv cells can be measured by calculating how much they can convert sunlight into usable energy for human consumption. Maximum efficiency of a solar photovoltaic cell is given by the following equation: η(maximum efficiency)= P(maximum power output)/(E(S,γ)(incident radiation flux)*A(c)(Area of collector)).[24] If the area provided is limited, efficiency of the PV cell is important to achieve the desired power output over a limited area.The most efficient solar cell so far is a multi-junction concentrator solar cell with an efficiency of 43.5%[25] produced by Solar Junction in April 2011. The highest efficiencies achieved without concentration include Sharp Corporation at 35.8% using a proprietary triple-junction manufacturing technology in 2009,[26] and Boeing Spectrolab (40.7% also using a triple-layer design). The US company SunPower produces cells that have an energy conversion ratio of 19.5%, well above the market average of 12–18%.[27][citation needed]

There have been numerous attempts to cut down the costs of PV cells and modules to the point that will be both competitive and efficient. This can be achieved by significantly increasing the conversion efficiency of PV materials. In order to increase the efficiency of solar cells, it is necessary to choose the semiconductor material with appropriate energy gap that matches the solar spectrum. This will enhance their electrical, optical, and structural properties. Choosing a better approach to get more effective charge collection is also necessary to increase the efficiency. There are several groups of materials that fit into different efficiency regimes. Ultrahigh-efficiency devices (η>30%) [28]] are made by using GaAs and GaInP2 semiconductors with multijunction tandem cells.

High-quality, single-crystal silicon materials are used to achieve high-efficiency cells (η>20%).

Organic photovoltaic cells (OPVs) are also viable alternative that relieves energy pressure and environmental problems from increasing combustion of fossil fuels. Recent development of OPVs made a huge advancement of power conversion efficiency from 3% to over 15% [29]]. To date, the highest reported power conversion efficiency ranges from 6.7% to 8.94% for small molecule, 8.4%-10.6% for polymer OPVs, and 7% to 15% for perovskite OPVs [30]]. Not only does recent development of OPVs make them more efficient and low-cost, they also make it environmentally-benign and renewable.

Several companies have begun embedding power optimizers into PV modules called smart modules. These modules perform maximum power point tracking (MPPT) for each module individually, measure performance data for monitoring, and provide additional safety. Such modules can also compensate for shading effects, wherein a shadow falling across a section of a module causes the electrical output of one or more strings of cells in the module to fall to zero, but not having the output of the entire module fall to zero.[31]

At the end of September 2013, IKEA announced that solar panel packages for houses will be sold at 17 United Kingdom IKEA stores by the end of July 2014. The decision followed a successful pilot project at the Lakeside IKEA store, whereby one photovoltaic (PV) system was sold almost every day. The panels are manufactured by the Chinese company Hanergy.[32]

Growth

The 2014 European Photovoltaic Industry Association (EPIA) report estimates global PV installations to grow 35-52 GW in 2014. China is predicted to take the lead from Germany and to become the world's largest producer of PV power in 2016. By 2018 the worldwide photovoltaic capacity is projected to have doubled (low scenario of 320 GW) or even tripled (high scenario of 430 GW) within five years. The EPIA also estimates that photovoltaics will meet 10 to 15 percent of Europe's energy demand in 2030.

The EPIA/Greenpeace Solar Generation Paradigm Shift Scenario (formerly called Advanced Scenario) from 2010 shows that by the year 2030, 1,845 GW of PV systems could be generating approximately 2,646 TWh/year of electricity around the world. Combined with energy use efficiency improvements, this would represent the electricity needs of more than 9 percent of the world's population. By 2050, over 20 percent of all electricity could be provided by photovoltaics.[36]

Forecast

Michael Liebreich, from Bloomberg New Energy Finance, anticipates a tipping point for solar energy. The costs of power from wind and solar are already below those of conventional electricity generation in some parts of the world, as they have fallen sharply and will continue to do so. He also asserts, that the electrical grid has been greatly expanded worldwide, and is ready to receive and distribute electricity from renewable sources. In addition, worldwide electricity prices came under strong pressure from renewable energy sources, that are, in part, enthusiastically embraced by consumers.[37]Deutsche Bank sees a "second gold rush" for the photovoltaic industry to come. Grid parity has already been reached in at least 19 markets by January 2014. Photovoltaics will prevail beyond feed-in tariffs, becoming more competitive as deployment increases and prices continue to fall.[38]

In June 2014 Barclays downgraded bonds of U.S. utility companies. Barclays expects more competition by a growing self-consumption due to a combination of decentralized PV-systems and residential electricity storage. This could fundamentally change the utility's business model and transform the system over the next ten years, as prices for these systems are predicted to fall.[39]

Environmental impacts of photovoltaic technologies

PV technologies have shown significant progress lately in terms of annual production capacity and life cycle environmental performances, which necessitates the assessment of environmental impacts of such technologies. The different PV technologies show slight variations in the emissions when compared the emissions from conventional energy technologies that replaced by the latest PV technologies.[40] With the up scaling of thin film module production for meeting future energy needs, there is a growing need for conducting the life cycle assessment of such technologies to analyze the future environmental impacts resulting from such technologies.[41]The manufacturing processes of solar cell involve the emissions of several toxic, flammable and explosive chemicals. Lately, in the field of photovoltaic research, there has been a continual rise in research and development efforts focused on reducing mass during cell manufacture. Such efforts have resulted in reducing the thickness of solar cells and thus the next generation solar cells are becoming thinner and eventually risks of exposure are reduced nevertheless, all chemicals must be carefully handled to ensure minimal human and environmental contact. The large scale deployment of such renewable energy technologies could result in potential negative environmental implications. These potential problems can pose serious challenges in promulgating such technologies to a broad segment of consumers (Evans, Strezov, & Evans, 2009; Tsoutsos, Frantzeskaki, & Gekas, 2005; Vasilis M Fthenakis, 2003). [42] [43] [44]

There are studies which have shown that the PV environmental impacts come mainly from the production of the cells; operation and maintenance requirements and associated impacts are relatively small. However, in a more recent study by Collier, Wu, and Apul (2014),[45] they conducted the life cycle assessment for CZTS and Zn3P2 PV technologies for the first time. In this study, the cradle to gate environmental impacts from CZTS and Zn3P2 are assessed and compared with those from current commercial PV technologies such as CdTe and CIGS. The four impacts including Primary energy demand (PED), Global warming Potential (GWP), freshwater use and eco-toxicity were primarily studied. For all four impacts studied, CdTe and Zn3P2 performed better than CIGS and CZTS. In general, the contribution of raw (absorber) material extraction and processing to the total impacts was low compared with impacts coming from electricity consumption during manufacturing. Therefore, to reduce environmental impact, future PV technology development should focus more on the process improvement.[45] The future research should also focus on the water-energy nexus as it is crucial to understand the water impacts of potential PV technologies in order to better manage our water resources.

Economics

The PV industry has seen dramatic drops in module prices since 2008. In late 2011, factory-gate prices for crystalline-silicon photovoltaic modules dropped below the $1.00/W mark. The $1.00/W installed cost, is often regarded in the PV industry as marking the achievement of grid parity for PV. Technological advancements, manufacturing process improvements, and industry re-structuring, mean that further price reductions are likely in coming years.[2]

Financial incentives for photovoltaics, such as feed-in tariffs, have often been offered to electricity consumers to install and operate solar-electric generating systems. Government has sometimes also offered incentives in order to encourage the PV industry to achieve the economies of scale needed to compete where the cost of PV-generated electricity is above the cost from the existing grid. Such policies are implemented to promote national or territorial energy independence, high tech job creation and reduction of carbon dioxide emissions which cause global warming. Due to economies of scale solar panels get less costly as people use and buy more—as manufacturers increase production to meet demand, the cost and price is expected to drop in the years to come.

Solar cell efficiencies vary from 6% for amorphous silicon-based solar cells to 44.0% with multiple-junction concentrated photovoltaics.[47] Solar cell energy conversion efficiencies for commercially available photovoltaics are around 14–22%.[48][49] Concentrated photovoltaics (CPV) may reduce cost by concentrating up to 1,000 suns (through magnifying lens) onto a smaller sized photovoltaic cell. However, such concentrated solar power requires sophisticated heat sink designs, otherwise the photovoltaic cell overheats, which reduces its efficiency and life. To further exacerbate the concentrated cooling design, the heat sink must be passive, otherwise the power required for active cooling would reduce the overall efficiency and economy.

Crystalline silicon solar cell prices have fallen from $76.67/Watt in 1977 to an estimated $0.74/Watt in 2013.[50] This is seen as evidence supporting Swanson's law, an observation similar to the famous Moore's Law that states that solar cell prices fall 20% for every doubling of industry capacity.[50]

As of 2011, the price of PV modules has fallen by 60% since the summer of 2008, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates, putting solar power for the first time on a competitive footing with the retail price of electricity in a number of sunny countries; an alternative and consistent price decline figure of 75% from 2007 to 2012 has also been published,[51] though it is unclear whether these figures are specific to the United States or generally global. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) from PV is competitive with conventional electricity sources in an expanding list of geographic regions,[5] particularly when the time of generation is included, as electricity is worth more during the day than at night.[52] There has been fierce competition in the supply chain, and further improvements in the levelised cost of energy for solar lie ahead, posing a growing threat to the dominance of fossil fuel generation sources in the next few years.[53] As time progresses, renewable energy technologies generally get cheaper,[54][55] while fossil fuels generally get more expensive:

The less solar power costs, the more favorably it compares to conventional power, and the more attractive it becomes to utilities and energy users around the globe. Utility-scale solar power can now be delivered in California at prices well below $100/MWh ($0.10/kWh) less than most other peak generators, even those running on low-cost natural gas. Lower solar module costs also stimulate demand from consumer markets where the cost of solar compares very favorably to retail electric rates.[56]As of 2011, the cost of PV has fallen well below that of nuclear power and is set to fall further. The average retail price of solar cells as monitored by the Solarbuzz group fell from $3.50/watt to $2.43/watt over the course of 2011.[57]

For large-scale installations, prices below $1.00/watt were achieved. A module price of 0.60 Euro/watt ($0.78/watt) was published for a large scale 5-year deal in April 2012.[58]By the end of 2012, the "best in class" module price had dropped to $0.50/watt, and was expected to drop to $0.36/watt by 2017.[59]

In many locations, PV has reached grid parity, which is usually defined as PV production costs at or below retail electricity prices (though often still above the power station prices for coal or gas-fired generation without their distribution and other costs). However, in many countries there is still a need for more access to capital to develop PV projects. To solve this problem securitization has been proposed and used to accelerate development of solar photovoltaic projects.[60][61] For example, SolarCity offered, the first U.S. asset-backed security in the solar industry in 2013.[62]

Photovoltaic power is also generated during a time of day that is close to peak demand (precedes it) in electricity systems with high use of air conditioning. More generally, it is now evident that, given a carbon price of $50/ton, which would raise the price of coal-fired power by 5c/kWh, solar PV will be cost-competitive in most locations. The declining price of PV has been reflected in rapidly growing installations, totaling about 23 GW in 2011. Although some consolidation is likely in 2012, due to support cuts in the large markets of Germany and Italy, strong growth seems likely to continue for the rest of the decade. Already, by one estimate, total investment in renewables for 2011 exceeded investment in carbon-based electricity generation.[57]

In the case of self consumption payback time is calculated based on how much electricity is not brought from the grid. Additionally, using PV solar power to charge DC batteries, as used in Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Electric Vehicles, leads to greater efficiencies. Traditionally, DC generated electricity from solar PV must be converted to AC for buildings, at an average 10% loss during the conversion. An additional efficiency loss occurs in the transition back to DC for battery driven devices and vehicles, and using various interest rates and energy price changes were calculated to find present values that range from $2,057.13 to $8,213.64 (analysis from 2009).[63]

For example in Germany with electricity prices of 0.25 euro/kWh and Insolation of 900 kWh/kW one kWp will save 225 euro per year and with installation cost of 1700 euro/kWp means that the system will pay back in less than 7 years.[64]

Applications

A glimpse of the 168 MW Solarpark Senftenberg/Schipkau, built on former open-pit mining areas in Eastern Germany.

Power stations

Many solar photovoltaic power stations have been built, mainly in Europe.[65] As of July 2012, the largest photovoltaic (PV) power plants in the world are the Agua Caliente Solar Project (USA, 247 MW), Charanka Solar Park (India, 214 MW), Golmud Solar Park (China, 200 MW), Perovo Solar Park (Ukraine, 100 MW), Sarnia Photovoltaic Power Plant (Canada, 97 MW), Brandenburg-Briest Solarpark (Germany 91 MW), Solarpark Finow Tower (Germany 84.7 MW), Montalto di Castro Photovoltaic Power Station (Italy, 84.2 MW), Eggebek Solar Park (Germany 83.6 MW), Senftenberg Solarpark (Germany, 82 MW), Finsterwalde Solar Park (Germany, 80.7 MW), Okhotnykovo Solar Park (Ukraine, 80 MW), Lopburi Solar Farm (Thailand, 73.16 MW), Rovigo Photovoltaic Power Plant (Italy, 72 MW), and the Lieberose Photovoltaic Park (Germany, 71.8 MW).[65]There are also many large plants under construction. The Desert Sunlight Solar Farm under construction in Riverside County, California and Topaz Solar Farm being built in San Luis Obispo County, California are both 550 MW solar parks that will use thin-film solar photovoltaic modules made by First Solar.[66] The Blythe Solar Power Project is a 500 MW photovoltaic station under construction in Riverside County, California. The California Valley Solar Ranch (CVSR) is a 250 MW solar photovoltaic power plant, which is being built by SunPower in the Carrizo Plain, northeast of California Valley.[67] The 230 MW Antelope Valley Solar Ranch is a First Solar photovoltaic project which is under construction in the Antelope Valley area of the Western Mojave Desert, and due to be completed in 2013.[68] The Mesquite Solar project is a photovoltaic solar power plant being built in Arlington, Maricopa County, Arizona, owned by Sempra Generation.[69] Phase 1 will have a nameplate capacity of 150 megawatts.[70]

Many of these plants are integrated with agriculture and some use innovative tracking systems[71] that follow the sun's daily path across the sky to generate more electricity than conventional fixed-mounted systems. There are no fuel costs or emissions during operation of the power stations.

In buildings

Photovoltaic arrays are often associated with buildings: either integrated into them, mounted on them or mounted nearby on the ground.Arrays are most often retrofitted into existing buildings, usually mounted on top of the existing roof structure or on the existing walls. Alternatively, an array can be located separately from the building but connected by cable to supply power for the building. In 2010, more than four-fifths of the 9,000 MW of solar PV operating in Germany were installed on rooftops.[72] Building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) are increasingly incorporated into new domestic and industrial buildings as a principal or ancillary source of electrical power.[73] Typically, an array is incorporated into the roof or walls of a building. Roof tiles with integrated PV cells are also common. A 2011 study using thermal imaging has shown that solar panels, provided there is an open gap in which air can circulate between them and the roof, provide a passive cooling effect on buildings during the day and also keep accumulated heat in at night.[74]

The power output of photovoltaic systems for installation in buildings is usually described in kilowatt-peak units (kWp).

In transport

Winner of the South African Solar Challenge

PV has traditionally been used for electric power in space. PV is rarely used to provide motive power in transport applications, but is being used increasingly to provide auxiliary power in boats and cars. Some automobiles are fitted with solar-powered air conditioning to limit interior temperatures on hot days.[75] A self-contained solar vehicle would have limited power and utility, but a solar-charged electric vehicle allows use of solar power for transportation. Solar-powered cars, boats[76] and airplanes[77] have been demonstrated, with the most practical and likely of these being solar cars.[78]

Standalone devices

Until a decade or so ago, PV was used frequently to power calculators and novelty devices. Improvements in integrated circuits and low power liquid crystal displays make it possible to power such devices for several years between battery changes, making PV use less common. In contrast, solar powered remote fixed devices have seen increasing use recently in locations where significant connection cost makes grid power prohibitively expensive. Such applications include solar lamps, water pumps,[79] parking meters,[80][81] emergency telephones, trash compactors,[82] temporary traffic signs, charging stations,[83][84] and remote guard posts and signals.

Rural electrification

Developing countries where many villages are often more than five kilometers away from grid power are increasingly using photovoltaics. In remote locations in India a rural lighting program has been providing solar powered LED lighting to replace kerosene lamps. The solar powered lamps were sold at about the cost of a few months' supply of kerosene.[85][86] Cuba is working to provide solar power for areas that are off grid.[87] More complex applications of off-grid solar energy use include 3D printers.[88] RepRap 3D printers have been solar powered with photovoltaic technology,[89] which enables distributed manufacturing for sustainable development.These are areas where the social costs and benefits offer an excellent case for going solar, though the lack of profitability has relegated such endeavors to humanitarian efforts. However, solar rural electrification projects have been difficult to sustain due to unfavorable economics, lack of technical support, and a legacy of ulterior motives of north-to-south technology transfer.[90]

Solar roadways

The 104 kW photovoltaic system along the highways Interstate 5 and Interstate 205 near Tualatin, Oregon in December 2008.

A 45 mi (72 km) section of roadway in Idaho is being used to test the possibility of installing solar panels into the road surface, as roads are generally unobstructed to the sun and represent about the percentage of land area needed to replace other energy sources with solar power.[92]

Floatovoltaics

In May 2008, the Far Niente Winery in Oakville, CA pioneered the world's first "floatovoltaic" system by installing 994 photovoltaic solar panels onto 130 pontoons and floating them on the winery's irrigation pond. The floating system generates about 477 kW of peak output and when combined with an array of cells located adjacent to the pond is able to fully offset the winery's electricity consumption.[93]The primary benefit of a floatovoltaic system is that it avoids the need to sacrifice valuable land area that could be used for another purpose. In the case of the Far Niente Winery, the floating system saved three-quarters of an acre that would have been required for a land-based system. That land area can instead be used to grow an amount of grapes able to produce $150,000 of bottled wine.[94] Another benefit of a floatovoltaic system is that the panels are kept at a lower temperature than they would be on land, leading to a higher efficiency of solar energy conversion.

The floating panels also reduce the amount of water lost through evaporation and inhibit the growth of algae.[95]

Plug-in solar

In 2012, a UL approved solar panel was introduced that is simply plugged into an electrical outlet. It senses mains voltage and waits for five minutes before activating the inverter, and shuts down immediately if line voltage is removed, eliminating any shock hazard from touching the plug prongs. Up to five 240-watt panels can be connected to one outlet.[96]Dye solar cells

The dye solar cell module is very young photovoltaic technology, The ultimate aim is the successful integration of solar modules into the building facade. Researchers at the Fraunhofer ISE have succeeded in producing the worldwide first dye solar cell module.[97]Telecommunication and signaling

Solar PV power is ideally suited for telecommunication applications such as local telephone exchange, radio and TV broadcasting, microwave and other forms of electronic communication links. This is because, in most telecommunication application, storage batteries are already in use and the electrical system is basically DC. In hilly and mountainous terrain, radio and TV signals may not reach as they get blocked or reflected back due to undulating terrain. At these locations, low power transmitters (LPT) are installed to receive and retransmit the signal for local population.[98]Spacecraft applications

Spacecraft operating in the inner solar system usually rely on the use of solar panels to derive electricity from sunlight.

Photovoltaic solar cells on spacecraft was one of the earliest applications of photovoltaic cells. The first spacecraft to use solar panels was the Vanguard 1 satellite, launched by the US in 1958.[99]

Solar panels on spacecraft supply power for two principal uses:

- power to run the sensors, active heating and cooling, and telemetry.

- power for spacecraft propulsion—electric propulsion, sometimes called solar-electric propulsion.[100] See also energy needed for propulsion methods.

Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector

Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collectors, sometimes known as hybrid PV/T systems or PVT, are systems that convert solar radiation into thermal and electrical energy. These systems combine a photovoltaic cell, which converts electromagnetic radiation (photons) into electricity, with a solar thermal collector, which captures the remaining energy and removes waste heat from the PV module. The capture of both electricity and heat allow these devices to have higher exergy[101] and thus be more overall energy efficient than solar photovoltaic (PV) or solar thermal alone.[102]Advantages

The 122 PW of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface is plentiful—almost 10,000 times more than the 13 TW equivalent of average power consumed in 2005 by humans.[103] This abundance leads to the suggestion that it will not be long before solar energy will become the world's primary energy source.[104] Additionally, solar electric generation has the highest power density (global mean of 170 W/m2) among renewable energies.[103]Solar power is pollution-free during use. Production end-wastes and emissions are manageable using existing pollution controls. End-of-use recycling technologies are under development[105] and policies are being produced that encourage recycling from producers.[106]

PV installations can operate for 100 years or even more[107] with little maintenance or intervention after their initial set-up, so after the initial capital cost of building any solar power plant, operating costs are extremely low compared to existing power technologies.

Grid-connected solar electricity can be used locally thus reducing transmission/distribution losses (transmission losses in the US were approximately 7.2% in 1995).[108]

Compared to fossil and nuclear energy sources, very little research money has been invested in the development of solar cells, so there is considerable room for improvement. Nevertheless, experimental high efficiency solar cells already have efficiencies of over 40% in case of concentrating photovoltaic cells[109] and efficiencies are rapidly rising while mass-production costs are rapidly falling.[110]

In some states of the United States, much of the investment in a home-mounted system may be lost if the home-owner moves and the buyer puts less value on the system than the seller. The city of Berkeley developed an innovative financing method to remove this limitation, by adding a tax assessment that is transferred with the home to pay for the solar panels.[111] Now known as PACE, Property Assessed Clean Energy, 28 U.S. states have duplicated this solution.[112]

There is evidence, at least in California, that the presence of a home-mounted solar system can actually increase the value of a home. According to a paper published in April 2011 by the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory titled An Analysis of the Effects of Residential Photovoltaic Energy Systems on Home Sales Prices in California:

The research finds strong evidence that homes with PV systems in California have sold for a premium over comparable homes without PV systems. More specifically, estimates for average PV premiums range from approximately $3.9 to $6.4 per installed watt (DC) among a large number of different model specifications, with most models coalescing near $5.5/watt. That value corresponds to a premium of approximately $17,000 for a relatively new 3,100 watt PV system (the average size of PV systems in the study).[113]