Sustainability (from the latin sustinere - hold up, hold upright; furnish with means of support; bear, undergo, endure) is the ability to continue over a long period of time. In modern usage it generally refers to a state in which the environment, economy, and society will continue to exist over a long period of time. Many definitions emphasize the environmental dimension. This can include addressing key environmental problems, such as climate change and biodiversity loss. The idea of sustainability can guide decisions at the global, national, organizational, and individual levels. A related concept is that of sustainable development, and the terms are often used to mean the same thing. UNESCO distinguishes the two like this: "Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it."

Details around the economic dimension of sustainability are controversial. Scholars have discussed this under the concept of weak and strong sustainability. For example, there will always be tension between the ideas of "welfare and prosperity for all" and environmental conservation, so trade-offs are necessary. It would be desirable to find ways that separate economic growth from harming the environment. This means using fewer resources per unit of output even while growing the economy. This decoupling reduces the environmental impact of economic growth, such as pollution. Doing this is difficult.

It is challenging to measure sustainability as the concept is complex, contextual, and dynamic. Indicators have been developed to cover the environment, society, or the economy but there is no fixed definition of sustainability indicators. The metrics are evolving and include indicators, benchmarks, and audits. They include sustainability standards and certification systems, like Fairtrade and Organic. They also involve indices and accounting systems, such as corporate sustainability reporting and triple Bottom Line accounting.

It is necessary to address many barriers to sustainability to achieve a sustainability transition or sustainability transformation. Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity while others are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. For example, they can result from the dominant institutional frameworks in countries.

Global issues of sustainability are difficult to tackle because they need global solutions. Existing global organizations such as the UN and WTO are seen as inefficient in enforcing current global regulations. One reason for this is the lack of suitable sanctioning mechanisms. Governments are not the only sources of action for sustainability. For example, business groups have tried to integrate ecological concerns with economic activity, seeking sustainable business. Religious leaders have stressed the need for caring for nature and environmental stability. Individuals can also choose to live more sustainably.

Some people have criticized the idea of sustainability. One point of criticism is that the concept is vague and only a buzzword. Another is that sustainability might be an impossible goal. Some experts have pointed out that "no country is delivering what its citizens need without transgressing the biophysical planetary boundaries".

Some would say that sustainability is not a movement, it’s a way of life. It extends past saving the planet into saving yourself. To give your family and community a life that is sustainable for the next generation. A great example of this are the Kibbutzim in Israel that are self sustainable farm communities. The Amish also live a sustainable life. While some have chosen Homesteading (in modern times this terms usually refers to one buying a piece of land and living a self sufficient lifestyle including a self sufficient electric and water system).

Definitions

Current usage

Sustainability is regarded as a "normative concept". This means it is based on what people value or find desirable: "The quest for sustainability involves connecting what is known through scientific study to applications in pursuit of what people want for the future."

The 1983 UN Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission) had a big influence on the use of the term sustainability today. The commission's 1987 Brundtland Report provided a definition of sustainable development. The report, Our Common Future, defines it as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs". The report helped bring sustainability into the mainstream of policy discussions. It also popularized the concept of sustainable development.

Some other key concepts to illustrate the meaning of sustainability include:

- It may be a fuzzy concept, but in a positive sense: the goals are more important than the approaches or means applied.

- It connects with other essential concepts, such as resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability.

- Choices matter: "it is not possible to sustain everything, everywhere, forever".

- Scale matters in both space and time, and place matters.

- Limits exist (see planetary boundaries).

In everyday usage, sustainability often focuses on the environmental dimension.

Specific definitions

A single specific definition of sustainability may never be possible, but the concept is still useful. There have been attempts to define it, for example:

- "Sustainability can be defined as the capacity to maintain or improve the state and availability of desirable materials or conditions over the long term."

- "Sustainability [is] the long-term viability of a community, set of social institutions, or societal practice. In general, sustainability is understood as a form of intergenerational ethics in which the environmental and economic actions taken by present persons do not diminish the opportunities of future persons to enjoy similar levels of wealth, utility, or welfare."

- "Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In addition to natural resources, we also need social and economic resources. Sustainability is not just environmentalism. Embedded in most definitions of sustainability we also find concerns for social equity and economic development."

Some definitions focus on the environmental dimension. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines sustainability as: "the property of being environmentally sustainable; the degree to which a process or enterprise is able to be maintained or continued while avoiding the long-term depletion of natural resources".

Historical usage

The term sustainability is derived from the Latin word sustinere. "To sustain" can mean to maintain, support, uphold, or endure. So sustainability is the ability to continue over a long period of time.

In the past, sustainability referred to environmental sustainability. It meant using natural resources so that people in the future could continue to rely on them in the long term. The concept of sustainability, or Nachhaltigkeit in German, goes back to Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), and applied to forestry. The term for this now would be sustainable forest management. He used this term to mean the long-term responsible use of a natural resource. In his 1713 work Silvicultura oeconomica, he wrote that "the highest art/science/industriousness [...] will consist in such a conservation and replanting of timber that there can be a continuous, ongoing and sustainable use". The shift in use of "sustainability" from preservation of forests (for future wood production) to broader preservation of environmental resources (to sustain the world for future generations) traces to a 1972 book by Ernst Basler, based on a series of lectures at M.I.T.

The idea itself goes back a long time: Communities have always worried about the capacity of their environment to sustain them in the long term. Many ancient cultures, traditional societies, and indigenous peoples have restricted the use of natural resources.

Comparison to sustainable development

The terms sustainability and sustainable development are closely related. In fact, they are often used to mean the same thing. Both terms are linked with the "three dimensions of sustainability" concept. One distinction is that sustainability is a general concept, while sustainable development can be a policy or organizing principle. Scholars say sustainability is a broader concept because sustainable development focuses mainly on human well-being.

Sustainable development has two linked goals. It aims to meet human development goals. It also aims to enable natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services needed for economies and society. The concept of sustainable development has come to focus on economic development, social development and environmental protection for future generations.

Dimensions

Development of three dimensions

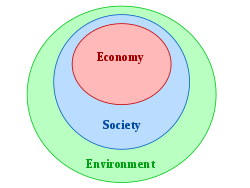

Scholars usually distinguish three different areas of sustainability. These are the environmental, the social, and the economic. Several terms are in use for this concept. Authors may speak of three pillars, dimensions, components, aspects, perspectives, factors, or goals. All mean the same thing in this context. The three dimensions paradigm has few theoretical foundations.

The popular three intersecting circles, or Venn diagram, representing sustainability first appeared in a 1987 article by the economist Edward Barbier.

Scholars rarely question the distinction itself. The idea of sustainability with three dimensions is a dominant interpretation in the literature.

In the Brundtland Report, the environment and development are inseparable and go together in the search for sustainability. It described sustainable development as a global concept linking environmental and social issues. It added sustainable development is important for both developing countries and industrialized countries:

The 'environment' is where we all live; and 'development' is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable. [...] We came to see that a new development path was required, one that sustained human progress not just in a few pieces for a few years, but for the entire planet into the distant future. Thus 'sustainable development' becomes a goal not just for the 'developing' nations, but for industrial ones as well.

— Our Common Future (also known as the Brundtland Report)

The Rio Declaration from 1992 is seen as "the foundational instrument in the move towards sustainability". It includes specific references to ecosystem integrity. The plan associated with carrying out the Rio Declaration also discusses sustainability in this way. The plan, Agenda 21, talks about economic, social, and environmental dimensions:

Countries could develop systems for monitoring and evaluation of progress towards achieving sustainable development by adopting indicators that measure changes across economic, social and environmental dimensions.

Agenda 2030 from 2015 also viewed sustainability in this way. It sees the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with their 169 targets as balancing "the three dimensions of sustainable development, the economic, social and environmental".

Hierarchy

Scholars have discussed how to rank the three dimensions of sustainability. Many publications state that the environmental dimension is the most important. (Planetary integrity or ecological integrity are other terms for the environmental dimension.)

Protecting ecological integrity is the core of sustainability according to many experts. If this is the case then its environmental dimension sets limits to economic and social development.

The diagram with three nested ellipses is one way of showing the three dimensions of sustainability together with a hierarchy: It gives the environmental dimension a special status. In this diagram, the environment includes society, and society includes economic conditions. Thus it stresses a hierarchy.

This nested hierarchy has led some scholars and Indigenous thinkers to call for decentering the human in sustainability discourse, arguing that ecological systems should not merely be valued for their utility to humans but as interdependent life systems with intrinsic worth.

Another model shows the three dimensions in a similar way: In this SDG wedding cake model, the economy is a smaller subset of the societal system. And the societal system in turn is a smaller subset of the biosphere system.

In 2022 an assessment examined the political impacts of the Sustainable Development Goals. The assessment found that the "integrity of the earth's life-support systems" was essential for sustainability. The authors said that "the SDGs fail to recognize that planetary, people and prosperity concerns are all part of one earth system, and that the protection of planetary integrity should not be a means to an end, but an end in itself". The aspect of environmental protection is not an explicit priority for the SDGs. This causes problems as it could encourage countries to give the environment less weight in their developmental plans. The authors state that "sustainability on a planetary scale is only achievable under an overarching Planetary Integrity Goal that recognizes the biophysical limits of the planet".

Other frameworks bypass the compartmentalization of sustainability into separate dimensions completely.

Environmental sustainability

The environmental dimension is central to the overall concept of sustainability. People became more and more aware of environmental pollution in the 1960s and 1970s. This led to discussions on sustainability and sustainable development. This process began in the 1970s with concern for environmental issues. These included natural ecosystems or natural resources and the human environment. It later extended to all systems that support life on Earth, including human society.Reducing these negative impacts on the environment would improve environmental sustainability.

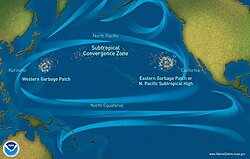

Environmental pollution is not a new phenomenon. But it has been only a local or regional concern for most of human history. Awareness of global environmental issues increased in the 20th century. The harmful effects and global spread of pesticides like DDT came under scrutiny in the 1960s. In the 1970s it emerged that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were depleting the ozone layer. This led to the de facto ban of CFCs with the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

In the early 20th century, Arrhenius discussed the effect of greenhouse gases on the climate (see also: history of climate change science). Climate change due to human activity became an academic and political topic several decades later. This led to the establishment of the IPCC in 1988 and the UNFCCC in 1992.

In 1972, the UN Conference on the Human Environment took place. It was the first UN conference on environmental issues. It stated it was important to protect and improve the human environment. It emphasized the need to protect wildlife and natural habitats:

The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and [...] natural ecosystems must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, as appropriate.

In 2000, the UN launched eight Millennium Development Goals. The aim was for the global community to achieve them by 2015. Goal 7 was to "ensure environmental sustainability". But this goal did not mention the concepts of social or economic sustainability.

Specific problems often dominate public discussion of the environmental dimension of sustainability: In the 21st century these problems have included climate change, biodiversity and pollution. Other global problems are loss of ecosystem services, land degradation, environmental impacts of animal agriculture and air and water pollution, including marine plastic pollution and ocean acidification. Many people worry about human impacts on the environment. These include impacts on the atmosphere, land, and water resources.

Human activities now have an impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems. This led Paul Crutzen to call the current geological epoch the Anthropocene.

The importance of citizens in accomplishing climate change adaptation, mitigation, and more general sustainable development objectives is being emphasized more and more by urban climate change governance (Hegger, Mees, & Wamsler, 2022). The Sustainable Development Goals and the Glasgow Climate Pact are two recent international agreements that acknowledge that sustainability transformations depend on both individual and social attitudes, values, and behaviors in addition to technical solutions (IPCC, 2022; Wamsler et al., 2021). Through their roles as voters, activists, consumers, and community members—particularly in decision-making, information co-production, and localized self-governance initiatives—citizens are seen as crucial change agents (Mees et al., 2016; Wamsler, 2017).

Economic sustainability

The economic dimension of sustainability is controversial. This is because the term development within sustainable development can be interpreted in different ways. Some may take it to mean only economic development and growth. This can promote an economic system that is bad for the environment. Others focus more on the trade-offs between environmental conservation and achieving welfare goals for basic needs (food, water, health, and shelter).

Economic development can indeed reduce hunger or energy poverty, especially in the least developed countries. That is why Sustainable Development Goal 8 calls for economic growth to drive social progress and well-being, where indicators include real GDP per capita growth. However, the challenge is to expand economic activities while reducing their environmental impact. In other words, humanity will have to find ways how societal progress (potentially by economic development) can be reached without excess strain on the environment.

The Brundtland report says poverty causes environmental problems. Poverty also results from them. So addressing environmental problems requires understanding the factors behind world poverty and inequality. The report demands a new development path for sustained human progress. It highlights that this is a goal for both developing and industrialized nations.

UNEP and UNDP launched the Poverty-Environment Initiative in 2005 which has three goals. These are reducing extreme poverty, greenhouse gas emissions, and net natural asset loss. This guide to structural reform will enable countries to achieve the SDGs. It should also show how to address the trade-offs between ecological footprint and economic development.

The government debt increases of many countries were found unsustainable in the long-term.

Social sustainability

The social dimension of sustainability is not well defined. One definition states that a society is sustainable in social terms if people do not face structural obstacles in key areas. These key areas are health, influence, competence, impartiality and meaning-making.

Some scholars place social issues at the very center of discussions. They suggest that all the domains of sustainability are social. These include ecological, economic, political, and cultural sustainability. These domains all depend on the relationship between the social and the natural. The ecological domain is defined as human embeddedness in the environment. From this perspective, social sustainability encompasses all human activities. It goes beyond the intersection of economics, the environment, and the social.

There are many broad strategies for more sustainable social systems. They include improved education and the political empowerment of women. This is especially the case in developing countries. They include greater regard for social justice. This involves equity between rich and poor both within and between countries. And it includes intergenerational equity. Providing more social safety nets to vulnerable populations would contribute to social sustainability. Current pension systems are financially unsustainable in some countries.

A society with a high degree of social sustainability would lead to livable communities with a good quality of life (being fair, diverse, connected and democratic).

Indigenous communities might have a focus on particular aspects of sustainability, for example spiritual aspects, community-based governance and an emphasis on place and locality.

Another aspect of social sustainability would be gender equity. According to reports from the United Nations and various research studies, women are disproportionately affected by climate related issues and sustainability efforts than men are. To name a few, natural disasters, carbon taxes, and public transportation expansions have all reportedly had unequal consequences on women and other marginalized groups by making it harder for them to afford different goods and services or newer transit routes (longer car rides equate to more gas purchases), as well as putting them at risk of becoming targets of violence.

These issues often go unaddressed and unheard, as women do not have the ability to voice these concerns due to the little to nonexistent presence of women in environmental policymaking. Despite the contrast in ability, women are often given the responsibility of solving the issues of climate change more than men are, due to the stereotypical feminine aspect of caring for the planet. For this reason, scholars urge the need for more female representation and leadership in environmental politics and policymaking. They also highlight the link between environmental and social sustainability and the importance of addressing the two together so that actual progress can be made, as policymakers often categorize and handle them separately. By improving healthcare, education, and representation in government, women will be empowered to have a voice in policy making.

Proposed additional dimensions

Some experts have proposed further dimensions. These could cover institutional, cultural, political, and technical dimensions.

Cultural sustainability

Some scholars have argued for a fourth dimension. They say the traditional three dimensions do not reflect the complexity of contemporary society. For example, Agenda 21 for culture and the United Cities and Local Governments argue that sustainable development should include a solid cultural policy. They also advocate for a cultural dimension in all public policies. Another example was the Circles of Sustainability approach, which included cultural sustainability.

Interactions between dimensions

Environmental and economic dimensions

People often debate the relationship between the environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability. In academia, this is discussed under the term weak and strong sustainability. In that model, the weak sustainability concept states that capital made by humans could replace most of the natural capital. Natural capital is a way of describing environmental resources. People may refer to it as nature. An example for this is the use of environmental technologies to reduce pollution.

The opposite concept in that model is strong sustainability. This assumes that nature provides functions that technology cannot replace. Thus, strong sustainability acknowledges the need to preserve ecological integrity. The loss of those functions makes it impossible to recover or repair many resources and ecosystem services. Biodiversity, along with pollination and fertile soils, are examples. Others are clean air, clean water, and regulation of climate systems.

Weak sustainability has come under criticism. It may be popular with governments and business but does not ensure the preservation of the earth's ecological integrity. This is why the environmental dimension is so important.

The World Economic Forum illustrated this in 2020. It found that $44 trillion of economic value generation depends on nature. This value, more than half of the world's GDP, is thus vulnerable to nature loss. Three large economic sectors are highly dependent on nature: construction, agriculture, and food and beverages. Nature loss results from many factors. They include land use change, sea use change and climate change. Other examples are natural resource use, pollution, and invasive alien species.

Trade-offs

Trade-offs between different dimensions of sustainability are a common topic for debate. Balancing the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability is difficult. This is because there is often disagreement about the relative importance of each. To resolve this, there is a need to integrate, balance, and reconcile the dimensions. For example, humans can choose to make ecological integrity a priority or to compromise it.

Some even argue the Sustainable Development Goals are unrealistic. Their aim of universal human well-being conflicts with the physical limits of Earth and its ecosystems.

Measurement tools

Sustainability measurement is a set of frameworks or indicators used to measure how sustainable something is. This includes processes, products, services and businesses. Sustainability is difficult to quantify and it may even be impossible to measure as there is no fixed definition. To measure sustainability, frameworks and indicators consider environmental, social and economic domains. The metrics vary by use case and are still evolving. They include indicators, benchmarks and audits. They include sustainability standards and certification systems like Fairtrade and Organic. They also involve indices and accounting. They can include assessment, appraisal and other reporting systems. The metrics are used over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales.

Environmental impacts of humans

There are several methods to measure or describe human impacts on Earth. They include the ecological footprint, ecological debt, carrying capacity, and sustainable yield. The idea of planetary boundaries is that there are limits to the carrying capacity of the Earth. It is important not to cross these thresholds to prevent irreversible harm to the Earth. These planetary boundaries involve several environmental issues. These include climate change and biodiversity loss. They also include types of pollution. These are biogeochemical (nitrogen and phosphorus), ocean acidification, land use, freshwater, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosols, and chemical pollution. (Since 2015 some experts refer to biodiversity loss as change in biosphere integrity. They refer to chemical pollution as introduction of novel entities.)

The IPAT formula measures the environmental impact of humans. It emerged in the 1970s. It states this impact is proportional to human population, affluence and technology. This implies various ways to increase environmental sustainability. One would be human population control. Another would be to reduce consumption and affluence such as energy consumption. Another would be to develop innovative or green technologies such as renewable energy.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment from 2005 measured 24 ecosystem services. It concluded that only four have improved over the last 50 years. It found 15 are in serious decline and five are in a precarious condition.

Economic costs

Experts in environmental economics have calculated the cost of using public natural resources. One project calculated the damage to ecosystems and biodiversity loss. This was the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity project from 2007 to 2011.

An entity that creates environmental and social costs often does not pay for them. The market price also does not reflect those costs. In the end, government policy is usually required to resolve this problem.

Decision-making can take future costs and benefits into account. The tool for this is the social discount rate. The bigger the concern for future generations, the lower the social discount rate should be. Another approach is to put an economic value on ecosystem services. This allows us to assess environmental damage against perceived short-term welfare benefits. One calculation is that, "for every dollar spent on ecosystem restoration, between three and 75 dollars of economic benefits from ecosystem goods and services can be expected".

In recent years, economist Kate Raworth has developed the concept of doughnut economics. This aims to integrate social and environmental sustainability into economic thinking. The social dimension acts as a minimum standard to which a society should aspire. The carrying capacity of the planet acts an outer limit.

Barriers

There are many reasons why sustainability is so difficult to achieve. These reasons have the name sustainability barriers. Before addressing these barriers it is important to analyze and understand them. Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity ("everything is related"). Others arise from the human condition. One example is the value-action gap. This reflects the fact that people often do not act according to their convictions. Experts describe these barriers as intrinsic to the concept of sustainability.

Other barriers are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. This means it is possible to overcome them. One way would be to put a price tag on the consumption of public goods. Some extrinsic barriers relate to the nature of dominant institutional frameworks. Examples would be where market mechanisms fail for public goods. Existing societies, economies, and cultures encourage increased consumption. There is a structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies. This inhibits necessary societal change.

Furthermore, there are several barriers related to the difficulties of implementing sustainability policies. There are trade-offs between the goals of environmental policies and economic development. Environmental goals include nature conservation. Development may focus on poverty reduction. There are also trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability. Political pressures generally favor the short term over the long term. So they form a barrier to actions oriented toward improving sustainability.

Barriers to sustainability may also reflect current trends. These could include consumerism and short-termism.

Conflicts, lack of international cooperation are also considered as a barrier to achieve sustainability. 61 scientists, including Michael Meeropol, Don Trent Jacobs and 24 organizations including Scientist Rebellion endorsed an appeal saying we can not stop the ecological crisis without stopping overconsumption and this is impossible as wars continue because GDP is directly linked to military potential.

Transition

Characteristics

Sustainability transformation (or transition), though not universally defined, refers to a deep, system-wide change affecting technology, economy, society, values, and goals. It is a complex and multi-layered process that must happen at all scales, from local communities to global governance institutions. However, it is often politically debated, as different stakeholders may disagree on both the goals and the methods of change. Additionally, such transformations can challenge existing power structures and resource distribution.

A sustainability transition requires major change in societies. They must change their fundamental values and organizing principles. These new values would emphasize "the quality of life and material sufficiency, human solidarity and global equity, and affinity with nature and environmental sustainability". A transition may only work if far-reaching lifestyle changes accompany technological advances.

Scientists have pointed out that: "Sustainability transitions come about in diverse ways, and all require civil-society pressure and evidence-based advocacy, political leadership, and a solid understanding of policy instruments, markets, and other drivers."

There are four possible overlapping processes of transformation. They each have different political dynamics. Technology, markets, government, or citizens can lead these processes.

The European Environment Agency defines a sustainability transition as "a fundamental and wide-ranging transformation of a socio-technical system towards a more sustainable configuration that helps alleviate persistent problems such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss or resource scarcities." The concept of sustainability transitions is similar to the concept of energy transitions.

One expert argues a sustainability transition must be "supported by a new kind of culture, a new kind of collaboration, [and] a new kind of leadership". It requires a large investment in "new and greener capital goods, while simultaneously shifting capital away from unsustainable systems".

In 2024 an interdisciplinary group of experts including Chip Fletcher, William J. Ripple, Phoebe Barnard, Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Christopher Field, David Karl, David King, Michael E. Mann and Naomi Oreskes advocated for a paradigm shift toward genuine sustainability and resource regeneration. They said that "such a transformation is imperative to reverse the tide of biodiversity loss due to overconsumption and to reinstate the security of food and water supplies, which are foundational for the survival of global populations."

Principles

It is possible to divide action principles to make societies more sustainable into four types. These are nature-related, personal, society-related and systems-related principles.

- Nature-related principles: decarbonize; reduce human environmental impact by efficiency, sufficiency and consistency; be net-positive – build up environmental and societal capital; prefer local, seasonal, plant-based and labor-intensive; polluter-pays principle; precautionary principle; and appreciate and celebrate the beauty of nature.

- Personal principles: practise contemplation, apply policies with caution, celebrate frugality.

- Society-related principles: grant the least privileged the greatest support; seek mutual understanding, trust and many wins; strengthen social cohesion and collaboration; engage stakeholders; foster education – share knowledge and collaborate.

- Systems-related principles: apply systems thinking; foster diversity; make what is relevant to the public more transparent; maintain or increase option diversity.

Example steps

There are many approaches that people can take to transition to environmental sustainability. These include maintaining ecosystem services, protecting and co-creating common resources, reducing food waste, and promoting dietary shifts towards plant-based foods. Another is reducing population growth by cutting fertility rates. Others are promoting new green technologies, and adopting renewable energy sources while phasing out subsidies to fossil fuels.

In 2017 scientists published an update to the 1992 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity. It showed how to move towards environmental sustainability. It proposed steps in three areas:

- Reduced consumption: reducing food waste, promoting dietary shifts towards mostly plant-based foods.

- Reducing the number of consumers: further reducing fertility rates and thus population growth.

- Technology and nature conservation: there are several related approaches. One is to maintain nature's ecosystem services. Another is promote new green technologies. Another is changing energy use. One aspect of this is to adopt renewable energy sources. At the same time it is necessary to end subsidies to energy production through fossil fuels.

Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, the United Nations agreed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Their official name is Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals. The UN described this programme as a very ambitious and transformational vision. It said the SDGs were of unprecedented scope and significance.

The UN said: "We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path."

The 17 goals and targets lay out transformative steps. For example, the SDGs aim to protect the future of planet Earth. The UN pledged to "protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations".

Options for overcoming barriers

Issues around economic growth

Eco-economic decoupling is an idea to resolve tradeoffs between economic growth and environmental conservation. The idea is to "decouple environmental bads from economic goods as a path towards sustainability". This would mean "using less resources per unit of economic output and reducing the environmental impact of any resources that are used or economic activities that are undertaken". The intensity of pollutants emitted makes it possible to measure pressure on the environment. This in turn makes it possible to measure decoupling. This involves following changes in the emission intensity associated with economic output. Examples of absolute long-term decoupling are rare. But some industrialized countries have decoupled GDP growth from production- and consumption-based CO2 emissions. Yet, even in this example, decoupling alone is not enough. It is necessary to accompany it with "sufficiency-oriented strategies and strict enforcement of absolute reduction targets".

One study in 2020 found no evidence of necessary decoupling. This was a meta-analysis of 180 scientific studies. It found that there is "no evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability" and that "in the absence of robust evidence, the goal of decoupling rests partly on faith". Some experts have questioned the possibilities for decoupling and thus the feasibility of green growth. Some have argued that decoupling on its own will not be enough to reduce environmental pressures. They say it would need to include the issue of economic growth. There are several reasons why adequate decoupling is currently not taking place. These are rising energy expenditure, rebound effects, problem shifting, the underestimated impact of services, the limited potential of recycling, insufficient and inappropriate technological change, and cost-shifting.

The decoupling of economic growth from environmental deterioration is difficult. This is because the entity that causes environmental and social costs does not generally pay for them. So the market price does not express such costs. For example, the cost of packaging into the price of a product. may factor in the cost of packaging. But it may omit the cost of disposing of that packaging. Economics describes such factors as externalities, in this case a negative externality. Usually, it is up to government action or local governance to deal with externalities.

For highly developed nations, sustainable practices and climate policies "often lead to conflicts between short-term economic interests and long-term environmental goals." However, for developing countries, efforts to address climate change are limited by their financial resources. To effectively advance sustainability, solutions need to focus on "fostering political commitment, enhancing inter-agency coordination, securing adequate funding, and engaging diverse stakeholders to overcome these challenges."

There are various ways to incorporate environmental and social costs and benefits into economic activities. Examples include: taxing the activity (the polluter pays); subsidizing activities with positive effects (rewarding stewardship); and outlawing particular levels of damaging practices (legal limits on pollution).

Government action and local governance

A textbook on natural resources and environmental economics stated in 2011: "Nobody who has seriously studied the issues believes that the economy's relationship to the natural environment can be left entirely to market forces." This means natural resources will be over-exploited and destroyed in the long run without government action.

Elinor Ostrom (winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics) expanded on this. She stated that local governance (or self-governance) can be a third option besides the market or the national government. She studied how people in small, local communities manage shared natural resources. She showed that communities using natural resources can establish rules their for use and maintenance. These are resources such as pastures, fishing waters, and forests. This leads to both economic and ecological sustainability. Successful self-governance needs groups with frequent communication among participants. In this case, groups can manage the usage of common goods without overexploitation. Based on Ostrom's work, some have argued that: "Common-pool resources today are overcultivated because the different agents do not know each other and cannot directly communicate with one another."

Global governance

Questions of global concern are difficult to tackle. That is because global issues need global solutions. But existing global organizations (UN, WTO, and others) do not have sufficient means. For example, they lack sanctioning mechanisms to enforce existing global regulations. Some institutions do not enjoy universal acceptance. An example is the International Criminal Court. Their agendas are not aligned (for example UNEP, UNDP, and WTO) And some accuse them of nepotism and mismanagement.

Multilateral international agreements, treaties, and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) face further challenges. These result in barriers to sustainability. Often these arrangements rely on voluntary commitments. An example is Nationally Determined Contributions for climate action. There can be a lack of enforcement of existing national or international regulation. And there can be gaps in regulation for international actors such as multi-national enterprises. Critics of some global organizations say they lack legitimacy and democracy. Institutions facing such criticism include the WTO, IMF, World Bank, UNFCCC, G7, G8 and OECD.

Responses by nongovernmental stakeholders

Businesses

Sustainable business practices integrate ecological concerns with social and economic ones. One accounting framework for this approach uses the phrase "people, planet, and profit". The name of this approach is the triple bottom line. The circular economy is a related concept. Its goal is to decouple environmental pressure from economic growth.

Growing attention towards sustainability has led to the formation of many organizations. These include the Sustainability Consortium of the Society for Organizational Learning, the Sustainable Business Institute, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Supply chain sustainability looks at the environmental and human impacts of products in the supply chain. It considers how they move from raw materials sourcing to production, storage, and delivery, and every transportation link on the way.

Religious communities

Religious leaders have stressed the importance of caring for nature and environmental sustainability. In 2015 over 150 leaders from various faiths issued a joint statement to the UN Climate Summit in Paris 2015. They reiterated a statement made in the Interfaith Summit in New York in 2014:

As representatives from different faith and religious traditions, we stand together to express deep concern for the consequences of climate change on the earth and its people, all entrusted, as our faiths reveal, to our common care. Climate change is indeed a threat to life, a precious gift we have received and that we need to care for.

Individuals

Individuals can also live in a more sustainable way. They can change their lifestyles, practise ethical consumerism, and embrace frugality. These sustainable living approaches can also make cities more sustainable. They do this by altering the built environment. Such approaches include sustainable transport, sustainable architecture, and zero emission housing. Research can identify the main issues to focus on. These include flying, meat and dairy products, car driving, and household sufficiency. Research can show how to create cultures of sufficiency, care, solidarity, and simplicity.

Some young people are using activism, litigation, and on-the-ground efforts to advance sustainability. This is particularly the case in the area of climate action.

Assessments and reactions

Impossible to reach

Scholars have criticized the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development from different angles. One was Dennis Meadows, one of the authors of the first report to the Club of Rome, called "The Limits to Growth". He argued many people deceive themselves by using the Brundtland definition of sustainability. This is because the needs of the present generation are actually not met today. Instead, economic activities to meet present needs will shrink the options of future generations. Another criticism is that the paradigm of sustainability is no longer suitable as a guide for transformation. This is because societies are "socially and ecologically self-destructive consumer societies".

Some scholars have even proclaimed the end of the concept of sustainability. This is because humans now have a significant impact on Earth's climate system and ecosystems. It might become impossible to pursue sustainability because of these complex, radical, and dynamic issues. Others have called sustainability a utopian ideal: "We need to keep sustainability as an ideal; an ideal which we might never reach, which might be utopian, but still a necessary one."

Vagueness

The term is often hijacked and thus can lose its meaning. People use it for all sorts of things, such as saving the planet to recycling your rubbish. A specific definition may never be possible. This is because sustainability is a concept that provides a normative structure. That describes what human society regards as good or desirable.

But some argue that while sustainability is vague and contested it is not meaningless. Although lacking in a singular definition, this concept is still useful. Scholars have argued that its fuzziness can actually be liberating. This is because it means that "the basic goal of sustainability (maintaining or improving desirable conditions [...]) can be pursued with more flexibility".

Confusion and greenwashing

Sustainability has a reputation as a buzzword. People may use the terms sustainability and sustainable development in ways that are different to how they are usually understood. This can result in confusion and mistrust. So a clear explanation of how the terms are being used in a particular situation is important.

Greenwashing is a practice of deceptive marketing. It is when a company or organization provides misleading information about the sustainability of a product, policy, or other activity. Investors are wary of this issue as it exposes them to risk. The reliability of eco-labels is also doubtful in some cases. Ecolabelling is a voluntary method of environmental performance certification and labelling for food and consumer products. The most credible eco-labels are those developed with close participation from all relevant stakeholders.