| Type 2 diabetes | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Diabetes mellitus type 2; adult-onset diabetes; noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) |

| |

| Universal blue circle symbol for diabetes | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Increased thirst, frequent urination, unexplained weight loss, increased hunger |

| Complications | Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, diabetic ketoacidosis, heart disease, strokes, diabetic retinopathy, kidney failure, amputations |

| Usual onset | Middle or older age |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Obesity, lack of exercise, genetics |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test |

| Prevention | Maintaining normal weight, exercising, eating properly |

| Treatment | Dietary changes, metformin, insulin, bariatric surgery |

| Prognosis | 10 year shorter life expectancy |

| Frequency | 392 million (2015) |

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes that is characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, and unexplained weight loss. Symptoms may also include increased hunger, feeling tired, and sores that do not heal. Often symptoms come on slowly. Long-term complications from high blood sugar include heart disease, strokes, diabetic retinopathy which can result in blindness, kidney failure, and poor blood flow in the limbs which may lead to amputations. The sudden onset of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state may occur; however, ketoacidosis is uncommon.

Type 2 diabetes primarily occurs as a result of obesity and lack of exercise. Some people are more genetically at risk than others. Type 2 diabetes makes up about 90% of cases of diabetes, with the other 10% due primarily to type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes. In type 1 diabetes there is a lower total level of insulin to control blood glucose, due to an autoimmune induced loss of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Diagnosis of diabetes is by blood tests such as fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, or glycated hemoglobin (A1C).

Type 2 diabetes is largely preventable by staying a normal weight, exercising regularly, and eating properly. Treatment involves exercise and dietary changes. If blood sugar levels are not adequately lowered, the medication metformin is typically recommended. Many people may eventually also require insulin injections. In those on insulin, routinely checking blood sugar levels is advised; however, this may not be needed in those taking pills. Bariatric surgery often improves diabetes in those who are obese.

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased markedly since 1960 in parallel with obesity. As of 2015 there were approximately 392 million people diagnosed with the disease compared to around 30 million in 1985. Typically it begins in middle or older age, although rates of type 2 diabetes are increasing in young people. Type 2 diabetes is associated with a ten-year-shorter life expectancy. Diabetes was one of the first diseases described. The importance of insulin in the disease was determined in the 1920s.

Signs and symptoms

Overview of the most significant symptoms of diabetes.

The classic symptoms of diabetes are polyuria (frequent urination), polydipsia (increased thirst), polyphagia (increased hunger), and weight loss. Other symptoms that are commonly present at diagnosis include a history of blurred vision, itchiness, peripheral neuropathy, recurrent vaginal infections, and fatigue. Many people, however, have no symptoms during the first few years and are diagnosed on routine testing. A small number of people with type 2 diabetes can develop a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (a condition of very high blood sugar associated with a decreased level of consciousness and low blood pressure).

Complications

Type 2 diabetes is typically a chronic disease associated with a ten-year-shorter life expectancy. This is partly due to a number of complications with which it is associated, including: two to four times the risk of cardiovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease and stroke; a 20-fold increase in lower limb amputations, and increased rates of hospitalizations. In the developed world, and increasingly elsewhere, type 2 diabetes is the largest cause of nontraumatic blindness and kidney failure. It has also been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia through disease processes such as Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Other complications include acanthosis nigricans, sexual dysfunction, and frequent infections. There is also an association between type 2 diabetes and mild hearing loss.

Cause

The development of type 2 diabetes is caused by a combination of lifestyle and genetic factors. While some of these factors are under personal control, such as diet and obesity, other factors are not, such as increasing age, female gender, and genetics. Obesity is more common in women than men in many parts of Africa. A lack of sleep has been linked to type 2 diabetes. This is believed to act through its effect on metabolism. The nutritional status of a mother during fetal development may also play a role, with one proposed mechanism being that of DNA methylation. The intestinal bacteria Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus have been connected with type 2 diabetes.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle factors are important to the development of type 2 diabetes, including obesity and being overweight (defined by a body mass index of greater than 25), lack of physical activity, poor diet, stress, and urbanization.

Excess body fat is associated with 30% of cases in those of Chinese and

Japanese descent, 60–80% of cases in those of European and African

descent, and 100% of cases in Pima Indians and Pacific Islanders. Among those who are not obese, a high waist–hip ratio is often present. Smoking appears to increase the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Dietary factors also influence the risk of developing type 2

diabetes. Consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks in excess is associated

with an increased risk. The type of fats in the diet are important, with saturated fats and trans fatty acids increasing the risk, and polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat decreasing the risk. Eating a lot of white rice appears to play a role in increasing risk. A lack of exercise is believed to cause 7% of cases. Persistent organic pollutants may play a role.

Genetics

Most cases of diabetes involve many genes, with each being a small contributor to an increased probability of becoming a type 2 diabetic. If one identical twin

has diabetes, the chance of the other developing diabetes within his

lifetime is greater than 90%, while the rate for nonidentical siblings

is 25–50%. As of 2011, more than 36 genes had been found that contribute to the risk of type 2 diabetes. All of these genes together still only account for 10% of the total heritable component of the disease. The TCF7L2 allele, for example, increases the risk of developing diabetes by 1.5 times and is the greatest risk of the common genetic variants. Most of the genes linked to diabetes are involved in beta cell functions.

There are a number of rare cases of diabetes that arise due to an abnormality in a single gene (known as monogenic forms of diabetes or "other specific types of diabetes"). These include maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY), Donohue syndrome, and Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome, among others. Maturity onset diabetes of the young constitute 1–5% of all cases of diabetes in young people.

Medical conditions

There are a number of medications and other health problems that can predispose to diabetes. Some of the medications include: glucocorticoids, thiazides, beta blockers, atypical antipsychotics, and statins. Those who have previously had gestational diabetes are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Other health problems that are associated include: acromegaly, Cushing's syndrome, hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, and certain cancers such as glucagonomas. Testosterone deficiency is also associated with type 2 diabetes.

Pathophysiology

Insulin resistance (right side) contributes to high glucose levels in the blood.

Type 2 diabetes is due to insufficient insulin production from beta cells in the setting of insulin resistance. Insulin resistance, which is the inability of cells to respond adequately to normal levels of insulin, occurs primarily within the muscles, liver, and fat tissue. In the liver, insulin normally suppresses glucose release. However, in the setting of insulin resistance, the liver inappropriately releases glucose into the blood.

The proportion of insulin resistance versus beta cell dysfunction

differs among individuals, with some having primarily insulin resistance

and only a minor defect in insulin secretion and others with slight

insulin resistance and primarily a lack of insulin secretion.

Other potentially important mechanisms associated with type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance include: increased breakdown of lipids within fat cells, resistance to and lack of incretin, high glucagon levels in the blood, increased retention of salt and water by the kidneys, and inappropriate regulation of metabolism by the central nervous system.

However, not all people with insulin resistance develop diabetes, since

an impairment of insulin secretion by pancreatic beta cells is also

required.

Diagnosis

| Condition | 2-hour glucose | Fasting glucose | HbA1c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | mmol/l(mg/dl) | mmol/l(mg/dl) | mmol/mol | DCCT % |

| Normal | <7 .8="" font=""> | <6 .1="" font=""> | <42 font=""> | <6 .0="" font=""> |

| Impaired fasting glycaemia | <7 .8="" font=""> | ≥6.1(≥110) & <7 .0="" font=""> | 42-46 | 6.0–6.4 |

| Impaired glucose tolerance | ≥7.8 (≥140) | <7 .0="" font=""> | 42-46 | 6.0–6.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | ≥11.1 (≥200) | ≥7.0 (≥126) | ≥48 | ≥6.5 |

The World Health Organization

definition of diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) is for a single raised

glucose reading with symptoms, otherwise raised values on two occasions,

of either:

- fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl)

- or

- with a glucose tolerance test, two hours after the oral dose a plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl)

A random blood sugar of greater than 11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl) in association with typical symptoms or a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of ≥ 48 mmol/mol (≥ 6.5 DCCT %) is another method of diagnosing diabetes. In 2009 an International Expert Committee that included representatives of the American Diabetes Association

(ADA), the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), and the European

Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) recommended that a

threshold of ≥ 48 mmol/mol (≥ 6.5 DCCT %) should be used to diagnose

diabetes. This recommendation was adopted by the American Diabetes Association in 2010.

Positive tests should be repeated unless the person presents with

typical symptoms and blood sugars >11.1 mmol/l (>200 mg/dl).

Threshold for diagnosis of diabetes is based on the relationship

between results of glucose tolerance tests, fasting glucose or HbA1c and complications such as retinal problems. A fasting or random blood sugar is preferred over the glucose tolerance test, as they are more convenient for people. HbA1c

has the advantages that fasting is not required and results are more

stable but has the disadvantage that the test is more costly than

measurement of blood glucose. It is estimated that 20% of people with diabetes in the United States do not realize that they have the disease.

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by high blood glucose in the context of insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency. This is in contrast to type 1 diabetes in which there is an absolute insulin deficiency due to destruction of islet cells in the pancreas and gestational diabetes that is a new onset of high blood sugars associated with pregnancy. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes can typically be distinguished based on the presenting circumstances. If the diagnosis is in doubt antibody testing may be useful to confirm type 1 diabetes and C-peptide levels may be useful to confirm type 2 diabetes, with C-peptide levels normal or high in type 2 diabetes, but low in type 1 diabetes.

Screening

No major organization recommends universal screening for diabetes as there is no evidence that such a program improve outcomes. Screening is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in adults without symptoms whose blood pressure is greater than 135/80 mmHg. For those whose blood pressure is less, the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against screening. There is no evidence that it changes the risk of death in this group of people. They also recommend screening among those who are overweight and between the ages of 40 and 70.

The World Health Organization recommends testing those groups at high risk and in 2014 the USPSTF is considering a similar recommendation. High-risk groups in the United States include: those over 45 years old; those with a first degree relative with diabetes; some ethnic groups, including Hispanics, African-Americans, and Native-Americans; a history of gestational diabetes; polycystic ovary syndrome; excess weight; and conditions associated with metabolic syndrome. The American Diabetes Association recommends screening those who have a BMI over 25 (in people of Asian descent screening is recommended for a BMI over 23).

Prevention

Onset of type 2 diabetes can be delayed or prevented through proper nutrition and regular exercise. Intensive lifestyle measures may reduce the risk by over half. The benefit of exercise occurs regardless of the person's initial weight or subsequent weight loss. High levels of physical activity reduce the risk of diabetes by about 28%. Evidence for the benefit of dietary changes alone, however, is limited, with some evidence for a diet high in green leafy vegetables and some for limiting the intake of sugary drinks.

There is an association between higher intake of sugar-sweetened fruit

juice and diabetes, but no evidence of an association with 100% fruit

juice. A 2019 review found evidence of benefit from dietary fiber.

In those with impaired glucose tolerance, diet and exercise either alone or in combination with metformin or acarbose may decrease the risk of developing diabetes. Lifestyle interventions are more effective than metformin.

A 2017 review found that, long term, lifestyle changes decreased the

risk by 28%, while medication does not reduce risk after withdrawal. While low vitamin D

levels are associated with an increased risk of diabetes, correcting

the levels by supplementing vitamin D3 does not improve that risk.

Management

Management of type 2 diabetes focuses on lifestyle interventions,

lowering other cardiovascular risk factors, and maintaining blood

glucose levels in the normal range. Self-monitoring of blood glucose for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes may be used in combination with education, although the benefit of self-monitoring in those not using multi-dose insulin is questionable. In those who do not want to measure blood levels, measuring urine levels may be done. Managing other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, high cholesterol, and microalbuminuria, improves a person's life expectancy. Decreasing the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg is associated with a lower risk of death and better outcomes.

Intensive blood pressure management (less than 130/80 mmHg) as opposed

to standard blood pressure management (less than 140-160 mmHg systolic

to 85–100 mmHg diastolic) results in a slight decrease in stroke risk

but no effect on overall risk of death.

Intensive blood sugar lowering (HbA1c<6 as="" ba="" blood="" lowering="" opposed="" standard="" sub="" sugar="" to="">1c

of 7–7.9%) does not appear to change mortality. The goal of treatment is typically an HbA1c

of 7 to 8% or a fasting glucose of less than 7.2 mmol/L (130 mg/dl);

however these goals may be changed after professional clinical

consultation, taking into account particular risks of hypoglycemia and life expectancy.

Despite guidelines recommending that intensive blood sugar control be

based on balancing immediate harms with long-term benefits, many

people – for example people with a life expectancy of less than nine

years who will not benefit, are over-treated.

It is recommended that all people with type 2 diabetes get regular eye examinations. There is weak evidence suggesting that treating gum disease by scaling and root planing may result in a small short-term improvement in blood sugar levels for people with diabetes. There is no evidence to suggest that this improvement in blood sugar levels is maintained longer than 4 months.

There is also not enough evidence to determine if medications to treat

gum disease are effective at lowering blood sugar levels.

Lifestyle

A proper diet and exercise are the foundations of diabetic care, with a greater amount of exercise yielding better results.

Exercise improves blood sugar control, decreases body fat content and

decreases blood lipid levels, and these effects are evident even without

weight loss. Aerobic exercise leads to a decrease in HbA1c and improved insulin sensitivity. Resistance training is also useful and the combination of both types of exercise may be most effective.

A diabetic diet that promotes weight loss is important. While the best diet type to achieve this is controversial, a low glycemic index diet or low carbohydrate diet has been found to improve blood sugar control. A very low calorie diet, begun shortly after the onset of type 2 diabetes, can result in remission of the condition. Viscous fiber supplements may be useful in those with diabetes.

Vegetarian diets

in general have been related to lower diabetes risk, but do not offer

advantages compared with diets which allow moderate amounts of animal

products. There is not enough evidence to suggest that cinnamon improves blood sugar levels in people with type 2 diabetes.

Culturally appropriate education may help people with type 2 diabetes control their blood sugar levels, for up to 24 months.

If changes in lifestyle in those with mild diabetes has not resulted in

improved blood sugars within six weeks, medications should then be

considered. There is not enough evidence to determine if lifestyle interventions affect mortality in those who already have DM2.

Medications

Metformin 500mg tablets.

There are several classes of anti-diabetic medications available. Metformin is generally recommended as a first line treatment as there is some evidence that it decreases mortality; however, this conclusion is questioned. Metformin should not be used in those with severe kidney or liver problems.

A second oral agent of another class or insulin may be added if metformin is not sufficient after three months. Other classes of medications include: sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs. As of 2015 there was no significant difference between these agents.

A 2018 review found that SGLT2 inhibitors may be better than

glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.

Rosiglitazone, a thiazolidinedione, has not been found to improve long-term outcomes even though it improves blood sugar levels. Additionally it is associated with increased rates of heart disease and death. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) prevent kidney disease and improve outcomes in those with diabetes. The similar medications angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) do not. A 2016 review recommended treating to a systolic blood pressure of 140 to 150 mmHg.

Injections of insulin may either be added to oral medication or used alone. Most people do not initially need insulin. When it is used, a long-acting formulation is typically added at night, with oral medications being continued. Doses are then increased to effect (blood sugar levels being well controlled). When nightly insulin is insufficient, twice daily insulin may achieve better control. The long acting insulins glargine and detemir are equally safe and effective, and do not appear much better than neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, but as they are significantly more expensive, they are not cost effective as of 2010. In those who are pregnant, insulin is generally the treatment of choice.

Vitamin D supplementation to people with type 2 diabetes may improve markers of insulin resistance and HbA1c.

Surgery

Weight loss surgery in those who are obese is an effective measure to treat diabetes. Many are able to maintain normal blood sugar levels with little or no medication following surgery and long-term mortality is decreased. There however is some short-term mortality risk of less than 1% from the surgery. The body mass index cutoffs for when surgery is appropriate are not yet clear.

It is recommended that this option be considered in those who are

unable to get both their weight and blood sugar under control.

Epidemiology

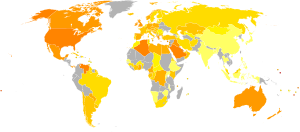

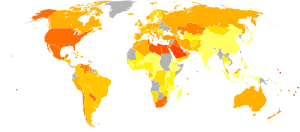

Regional rates of diabetes using data from 195 countries in 2014

Globally as of 2015 it was estimated that there were 392 million

people with type 2 diabetes making up about 90% of diabetes cases. This is equivalent to about 6% of the world's population. Diabetes is common both in the developed and the developing world. It remains uncommon, however, in the least developed countries.

Women seem to be at a greater risk as do certain ethnic groups, such as South Asians, Pacific Islanders, Latinos, and Native Americans. This may be due to enhanced sensitivity to a Western lifestyle in certain ethnic groups. Traditionally considered a disease of adults, type 2 diabetes is increasingly diagnosed in children in parallel with rising obesity rates. Type 2 diabetes is now diagnosed as frequently as type 1 diabetes in teenagers in the United States.

Rates of diabetes in 1985 were estimated at 30 million, increasing to 135 million in 1995 and 217 million in 2005.

This increase is believed to be primarily due to the global population

aging, a decrease in exercise, and increasing rates of obesity.

The five countries with the greatest number of people with diabetes as

of 2000 are India having 31.7 million, China 20.8 million, the United

States 17.7 million, Indonesia 8.4 million, and Japan 6.8 million. It is recognized as a global epidemic by the World Health Organization.

History

Diabetes is one of the first diseases described with an Egyptian manuscript from c. 1500 BCE mentioning "too great emptying of the urine." The first described cases are believed to be of type 1 diabetes. Indian physicians around the same time identified the disease and classified it as madhumeha or honey urine noting that the urine would attract ants. The term "diabetes" or "to pass through" was first used in 230 BCE by the Greek Apollonius Of Memphis. The disease was rare during the time of the Roman empire with Galen commenting that he had only seen two cases during his career.

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes were identified as separate conditions for the first time by the Indian physicians Sushruta and Charaka in 400–500 AD with type 1 associated with youth and type 2 with being overweight. The term "mellitus" or "from honey" was added by the Briton John Rolle in the late 1700s to separate the condition from diabetes insipidus which is also associated with frequent urination. Effective treatment was not developed until the early part of the 20th century when the Canadians Frederick Banting and Charles Best discovered insulin in 1921 and 1922. This was followed by the development of the long acting NPH insulin in the 1940s.