| Phineas P. Gage | |

|---|---|

Gage

and his "constant companion"—his inscribed tamping iron—sometime

after 1849, seen in the portrait (identified 2009) which "exploded the

common image of Gage as a dirty, disheveled misfit".

| |

| Born | July 9, 1823 (date uncertain) Grafton County, New Hampshire |

| Died | May 21, 1860 (aged 36) In or near San Francisco |

| Cause of death | Status epilepticus |

| Burial place | Cypress Lawn Memorial Park, California (skull in Warren Anatomical Museum, Boston) |

| Residence | |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Personality change after brain injury |

| Home town | Lebanon, New Hampshire |

| Spouse(s) | None |

| Children | None |

Phineas P. Gage (1823–1860) was an American railroad construction foreman remembered for his improbable survival of an accident in which a large iron rod was driven completely through his head, destroying much of his brain's left frontal lobe, and for that injury's reported effects on his personality and behavior over the remaining 12 years of his life—effects sufficiently profound (for a time at least) that friends saw him as "no longer Gage".

Gage is a fixture in the curricula of neurology, psychology, and neuroscience, one of "the great medical curiosities of all time" and "a living part of the medical folklore" frequently mentioned in books and scientific papers; he even has a minor place in popular culture. Despite this celebrity, the body of established fact about Gage and what he was like (whether before or after his injury) is small, which has allowed "the fitting of almost any theory [desired] to the small number of facts we have" —Gage acting as a "Rorschach inkblot" in which proponents of various conflicting theories of the brain all saw support for their views. Historically, published accounts of Gage (including scientific ones) have almost always severely exaggerated and distorted his behavioral changes, frequently contradicting the known facts.

A report of Gage's physical and mental condition shortly before his death implies that his most serious mental changes were temporary, so that in later life he was far more functional, and socially far better adapted, than in the years immediately following his accident. A social recovery hypothesis suggests that Gage's work as a stagecoach driver in Chile fostered this recovery by providing daily structure which allowed him to regain lost social and personal skills.

Life

Background

Cavendish, Vermont, 20 years after Gage's accident: (a) Region of the accident site; (t) Gage's lodgings, to which he was taken after his injury; (h) Harlow's home and surgery.

Gage was the first of five children born to Jesse Eaton Gage and Hannah Trussell (Swetland) Gage of Grafton County, New Hampshire. Little is known about his upbringing and education beyond that he was literate.

Town doctor John Martyn Harlow described Gage as "a perfectly healthy, strong and active young man, twenty-five years of age, nervo-bilious temperament, five feet six inches [168 cm] in height, average weight one hundred and fifty pounds [68 kg], possessing an iron will as well as an iron frame; muscular system unusually well developed—having had scarcely a day's illness from his childhood to the date of [his] injury". (In the pseudoscience of phrenology, which was then just ending its vogue, nervo-bilious denoted an unusual combination of "excitable and active mental powers" with "energy and strength [of] mind and body [making] possible the endurance of great mental and physical labor".)

Gage may have first worked with explosives on farms as a youth, or in nearby mines and quarries. He is known to have worked on construction of the Hudson River Railroad near Cortlandt Town, New York, and by the time of his accident he was a blasting foreman (possibly an independent contractor) on railway construction projects. His employers' "most efficient and capable foreman ... a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation", he had even commissioned a custom-made tamping iron—a large iron rod—for use in setting explosive charges.

Accident

Line of the Rutland & Burlington Railroad passing through "cut"

in rock south of Cavendish. Gage met with his accident while setting

explosives to create either this cut or a similar one nearby.

Explosive charge ready for fuse to be lit. tamping (sand) directs blast into surrounding rock.

Gage's

mouth was open at the moment of the explosion, and his skull

temporarily "hinged" open as the iron passed through, then was pulled

closed by the resilience of soft tissues once the iron had exited

through the top of

Gage's head.

Panel from Bring Me the Head of Phineas Gage, a portrayal of Gage in popular culture

As Gage was doing this around 4:30 p.m., his attention was attracted by his men working behind him. Looking over his right shoulder, and inadvertently bringing his head into line with the blast hole, Gage opened his mouth to speak; in that same instant the tamping iron sparked against the rock and (possibly because the sand had been omitted) the powder exploded. Rocketed from the hole, the tamping iron—1 1⁄4 inches (3.2 cm) in diameter, three feet seven inches (1.1 m) long, and weighing 13 1⁄4 pounds (6.0 kg)—entered the left side of Gage's face in an upward direction, just forward of the angle of the lower jaw. Continuing upward outside the upper jaw and possibly fracturing the cheekbone, it passed behind the left eye, through the left side of the brain, then completely out the top of the skull through the frontal bone.

Despite 19th-century references to Gage as the "American Crowbar Case", his tamping iron did not have the bend or claw sometimes associated with the term crowbar; rather, it was simply a pointed cylinder something like a javelin, round and fairly smooth:

The end which entered first is pointed; the taper being [eleven inches (27 cm) long, ending in a 1⁄4-inch (7 mm) point] ... circumstances to which the patient perhaps owes his life. The iron is unlike any other, and was made by a neighbouring blacksmith to please the fancy of the owner.The tamping iron landed point-first some 80 feet (25 m) away, "smeared with blood and brain".

Gage was thrown onto his back and gave some brief convulsions of the arms and legs, but spoke within a few minutes, walked with little assistance, and sat upright in an oxcart for the 3⁄4-mile (1.2 km) ride to his lodgings in town. About 30 minutes after the accident physician Edward H. Williams, finding Gage sitting in a chair outside the hotel, was greeted with "one of the great understatements of medical history":

When I drove up he said, "Doctor, here is business enough for you." I first noticed the wound upon the head before I alighted from my carriage, the pulsations of the brain being very distinct. The top of the head appeared somewhat like an inverted funnel, as if some wedge-shaped body had passed from below upward. Mr. Gage, during the time I was examining this wound, was relating the manner in which he was injured to the bystanders. I did not believe Mr. Gage's statement at that time, but thought he was deceived. Mr. Gage persisted in saying that the bar went through his head. Mr. G. got up and vomited; the effort of vomiting pressed out about half a teacupful of the brain [through the exit hole at the top of the skull], which fell upon the floor.Harlow took charge of the case around 6 p.m.:

You will excuse me for remarking here, that the picture presented was, to one unaccustomed to military surgery, truly terrific; but the patient bore his sufferings with the most heroic firmness. He recognized me at once, and said he hoped he was not much hurt. He seemed to be perfectly conscious, but was getting exhausted from the hemorrhage. His person, and the bed on which he was laid, were literally one gore of blood.

Initial treatment

A nightcap of the period

With Williams' assistance Harlow shaved the scalp around the region of the tamping iron's exit, then removed coagulated blood, small bone fragments, and "an ounce or more" of protruding brain. After probing for foreign bodies and replacing two large detached pieces of bone, Harlow closed the wound with adhesive straps, leaving it partially open for drainage; the entrance wound in the cheek was bandaged only loosely, for the same reason. A wet compress was applied, then a nightcap, then further bandaging to secure these dressings. Harlow also dressed Gage's hands and forearms (which along with his face had been "deeply burned") and ordered that Gage's head be kept elevated.

Late that evening Harlow noted: "Mind clear. Constant agitation of his legs, being alternately retracted and extended like the shafts of a fulling mill. Says he 'does not care to see his friends, as he shall be at work in a few days.'"

Convalescence

The

first known report of Gage's accident, understating the size of his

tamping iron (by confusing its diameter with its circumference)

and overstating damage to his jaw. "His fame is of the kind that is, and in his case literally so, thrust

upon otherwise ordinary people", writes Malcolm Macmillan.

Despite his own optimism, Gage's convalescence was long, difficult, and uneven. Though recognizing his mother and uncle—summoned from Lebanon, New Hampshire, 30 miles (50 km) away—on the morning after the accident, on the second day he "lost control of his mind, and became decidedly delirious". By the fourth day, he was again "rational ... knows his friends", and after a week's further improvement Harlow entertained, for the first time, the thought "that it was possible for Gage to recover ... This improvement, however, was of short duration."

Beginning 12 days after the accident, Gage was semi-comatose, "seldom speaking unless spoken to, and then answering only in monosyllables", and on the 13th day Harlow noted, "Failing strength ... coma deepened; the globe of the left eye became more protuberant, with ["fungus"—deteriorated, infected tissue] pushing out rapidly from the internal canthus [as well as] from the wounded brain, and coming out at the top of the head." By the 14th day, "The exhalations from the mouth and head [are] horribly fetid. Comatose, but will answer in monosyllables if aroused. Will not take nourishment unless strongly urged. The friends and attendants are in hourly expectancy of his death, and have his coffin and clothes in readiness."

The

entry damage to Gage's left cheek, and the raised bone fragment in the

exit area above his forehead, are visible in this plaster cast taken in

late 1849.

On the 24th day, Gage "succeeded in raising himself up, and took one step to his chair". One month later, he was walking "up and down stairs, and about the house, into the piazza", and while Harlow was absent for a week Gage was "in the street every day except Sunday", his desire to return to his family in New Hampshire being "uncontrollable by his friends ... he went without an overcoat and with thin boots; got wet feet and a chill". He soon developed a fever, but by mid-November he was "feeling better in every respect ... walking about the house again". Harlow's prognosis at this point: Gage "appears to be in a way of recovering, if he can be controlled".

Subsequent life and travels

"Disfigured yet still handsome". Note ptosis of the left eye and scar on forehead.

Injuries

In April 1849, Gage returned to Cavendish and visited Harlow, who noted at that time loss of vision (and ptosis) of the left eye, a large scar on the forehead (from Harlow's draining of the abscess) andupon the top of the head ... a quadrangular fragment of bone ... raised and quite prominent. Behind this is a deep depression, [2 in by 1 1/2 in wide, 5 cm by 4 cm], beneath which the pulsations of the brain can be perceived. Partial paralysis of the left side of the face. His physical health is good, and I am inclined to say he has recovered. Has no pain in head, but says it has a queer feeling which he is not able to describe.Gage's rearmost left upper molar, immediately adjacent to the point of entry through the cheek, was also lost. Though a year later some weakness remained, Harlow wrote that "physically, the recovery was quite complete during the four years immediately succeeding the injury".

New England and New York (1849–1852)

Phineas was accustomed to entertain his little nephews and nieces with the most fabulous recitals of his wonderful feats and hair-breadth escapes, without any foundation except in his fancy. He conceived a great fondness for pets and souvenirs, especially for children, horses and dogs—only exceeded by his attachment for his tamping iron, which was his constant companion during the remainder of his life.

J. M. Harlow (1868)

In November 1849, Henry Jacob Bigelow, the Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School, brought Gage to Boston for several weeks and, after satisfying himself that the tamping iron had actually passed through Gage's head, presented him to a meeting of the Boston Society for Medical Improvement and (possibly) to the medical school class.

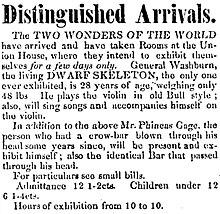

Gage appeared for a time at Barnum's American Museum in New York City.

"Admittance 12 1/2 cents" (equivalent to about $4 in 2017).

Gage briefly resumed exhibiting just before going to Chile, possibly

to help finance that move. This advertisement appeared August 1852 in Montpelier, Vermont.

For about 18 months, he worked for the owner of a stable and coach service in Hanover, New Hampshire.

Chile and California (1852–1860)

In August 1852, Gage was invited to Chile to work as a long-distance stagecoach driver there, "caring for horses, and often driving a coach heavily laden and drawn by six horses" on the Valparaíso–Santiago route. After his health began to fail in mid-1859, he left Chile for San Francisco, arriving (in his mother's words) "in a feeble condition, having failed very much since he left New Hampshire ... Had many ill turns while in Valparaiso, especially during the last year, and suffered much from hardship and exposure." In San Francisco he recovered under the care of his mother and sister, who had relocated there from New Hampshire around the time he went to Chile. Then, "anxious to work", he found employment with a farmer in Santa Clara.In February 1860, Gage began to have epileptic seizures. He lost his job, and (wrote Harlow) as the seizures increased in frequency and severity he "continued to work in various places [though he] could not do much".

Death and exhumation

New Hampshire Statesman, July 21, 1860

Gage's brother-in-law (a San Francisco city official) and his family personally delivered Gage's skull and iron to Harlow.

"[T]he

mother and friends, waiving the claims of personal and private

affection, with a magnanimity more than praiseworthy, at my request

have cheerfully placed this skull in my hands, for the benefit of

science." Gage's skull (sawn to show interior) and iron, photographed

for Harlow in 1868.

In 1866, Harlow (who had "lost all trace of [Gage], and had well nigh abandoned all expectation of ever hearing from him again") somehow learned that Gage had died in California, and made contact with his family there. At Harlow's request the family had Gage's skull exhumed, then personally delivered it to Harlow, who was by then a prominent physician, businessman, and civic leader in Woburn, Massachusetts.

About a year after the accident, Gage had given his tamping iron to Harvard Medical School's Warren Anatomical Museum, but he later reclaimed it

The tamping iron bears the following inscription, commissioned by Bigelow in conjunction with the iron's original deposit in the Museum (though the date given for the accident is one day off):

This is the bar that was shot through the head of Mr Phinehas[sic] P. Gage at Cavendish Vermont Sept 14,[sic] 1848. He fully recovered from the injury & deposited this bar in the Museum of the Medical College of Harvard University. • Phinehas P. Gage • Lebanon Grafton Cy N–H • Jan 6 1850The date Jan 6 1850 falls within the period during which Gage was in Boston under Bigelow's observation.

In 1940 Gage's headless remains were moved to Cypress Lawn Cemetery as part of a mandated relocation of San Francisco's dead to new resting places outside city limits

Excerpt from record book, Lone Mountain Cemetery, San Francisco, reflecting the May 23, 1860 interment of Phineas B.[sic] Gage by undertakers N. Gray & Co. (Position pointer over writing for transcription.)

Mental changes and brain damage

Mental changes

"I dressed him, God healed him." Dr. J. M. Harlow, who attended Gage after the "rude missile had been shot through his brain" and obtained his skull for study after his death. Shown here in later life, Harlow's interest in phrenology prepared him to accept that Gage's injury had changed his behavior.

"The leading feature of this case is its improbability." Harvard's Prof. H. J. Bigelow in 1854. His anti-localizationist training predisposed him to minimize Gage's behavioral changes.

Gage may have been the first case to suggest the brain's role in determining personality and that damage to specific parts of the brain might induce specific personality changes, but the nature, extent, and duration of these changes have been difficult to establish. Only a handful of sources give direct information on what Gage was like (either before or after the accident), the mental changes published after his death were much more dramatic than anything reported while he was alive, and few sources are explicit about the period of Gage's life to which each of their various descriptions of him (which vary widely in their implied level of functional impairment) is meant to apply.

Early observations (1849–1852)

Harlow ("virtually our only source of information" on Gage, according to psychologist Malcolm Macmillan) described the pre-accident Gage as hard-working, responsible, and "a great favorite" with the men in his charge, his employers having regarded him as "the most efficient and capable foreman in their employ"; he also took pains to note that Gage's memory and general intelligence seemed unimpaired after the accident, outside the periods of delirium. Nonetheless these same employers, after Gage's accident, "considered the change in his mind so marked that they could not give him his place again":The equilibrium or balance, so to speak, between his intellectual faculties and animal propensities, seems to have been destroyed. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operations, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animal passions of a strong man. Previous to his injury, although untrained in the schools, he possessed a well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation. In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was "no longer Gage".This description ("now routinely quoted", says Kotowicz) is from Harlow's observations set down soon after the accident, but Harlow—perhaps hesitant to describe his patient negatively while he was still alive—delayed publishing it until 1868, after Gage had died and his family had supplied "what we so much desired to see" (as Harlow termed Gage's skull).

In the interim, Harlow's 1848 report, published just as Gage was emerging from his convalescence, merely hinted at psychological symptoms:

The mental manifestations of the patient, I reserve to a future communication. I think the case ... is exceedingly interesting to the enlightened physiologist and intellectual philosopher.

"Before

the injury he was quiet and respectful." 1851 report apparently

based on information from Harlow, countering Bigelow's claim that

Gage was mentally unchanged.

But after Bigelow termed Gage "quite recovered in faculties of body and mind" with only "inconsiderable disturbance of function", a rejoinder in the American Phrenological Journal—

That there was no difference in his mental manifestations after the recovery [is] not true ... he was gross, profane, coarse, and vulgar, to such a degree that his society was intolerable to decent people.—was apparently based on information anonymously supplied by Harlow. Pointing out that Bigelow's extensive verbatim quotations from Harlow's 1848 papers omitted Harlow's promise to follow up with details of Gage's "mental manifestations", Barker explains Bigelow's and Harlow's contradictory evaluations (less than a year apart) by differences in their educational backgrounds, in particular their attitudes toward cerebral localization (the idea that different regions of the brain are specialized for different functions) and phrenology (the nineteenth-century pseudoscience that held that talents and personality can be inferred from the shape of a person's skull):

Harlow's interest in phrenology prepared him to accept the change in [Gage's] character as a significant clue to cerebral function which merited publication. Bigelow had [been taught] that damage to the cerebral hemispheres had no intellectual effect, and he was unwilling to consider Gage's deficit significant ... The use of a single case [including Gage's] to prove opposing views on phrenology was not uncommon.A reluctance to ascribe a biological basis to "higher mental functions" (functions—such as language, personality, and moral judgment—beyond the merely sensory and motor) may have been a further reason Bigelow discounted the behavioral changes in Gage which Harlow had noted.

Later observations (1852–1858)

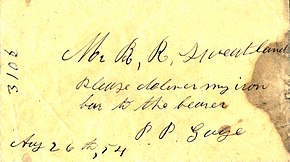

"Please deliver my iron bar to the bearer". While in Chile, Gage had his relative B. R. Sweetland retrieve the tamping iron from Harvard's Warren Anatomical Museum.

In 1860, an American physician who had known Gage in Chile described him as still "engaged in stage driving [and] in the enjoyment of good health, with no impairment whatever of his mental faculties". Together with the fact that Gage was hired by his employer in advance, in New England, to become part of the new coaching enterprise in Chile, this implies that Gage's most serious mental changes had been temporary, so that the "fitful, irreverent ... capricious and vacillating" Gage described by Harlow immediately post-accident became, over time, far more functional and socially far better adapted.

Macmillan writes that this conclusion is reinforced by the responsibilities and challenges associated with stagecoach work such as that done by Gage in Chile, including the requirement that drivers "be reliable, resourceful, and possess great endurance. But above all, they had to have the kind of personality that enabled them to get on well with their passengers."

Social recovery

A Concord stagecoach, likely the type driven by Gage in Chile

Macmillan writes that this contrast—between Gage's early, versus later, post-accident behavior—reflects his "[gradual change] from the commonly portrayed impulsive and uninhibited person into one who made a reasonable 'social recovery'", citing persons with similar injuries for whom "someone or something gave enough structure to their lives for them to relearn lost social and personal skills":

Phineas' survival and rehabilitation demonstrated a theory of recovery which has influenced the treatment of frontal lobe damage today. In modern treatment, adding structure to tasks by, for example, mentally visualising a written list, is considered a key method in coping with frontal lobe damage.According to contemporary accounts by visitors to Chile, Gage would have had to

rise early in the morning, prepare himself, and groom, feed, and harness the horses; he had to be at the departure point at a specified time, load the luggage, charge the fares and get the passengers settled; and then had to care for the passengers on the journey, unload their luggage at the destination, and look after the horses. The tasks formed a structure that required control of any impulsiveness he may have had.En route (Macmillan continues):

much foresight was required. Drivers had to plan for turns well in advance, and sometimes react quickly to manoeuvre around other coaches, wagons, and birlochos travelling at various speeds ... Adaptation had also to be made to the physical condition of the route: although some sections were well-made, others were dangerously steep and very rough.Thus Gage's stagecoach work—"a highly structured environment in which clear sequences of tasks were required [but within which] contingencies requiring foresight and planning arose daily"—resembles rehabilitation regimens first developed by Soviet neuropsychologist Alexander Luria for the reestablishment of self-regulation in World War II soldiers suffering frontal lobe injuries.

A neurological basis for such recoveries may be found in emerging evidence "that damaged [neural] tracts may re-establish their original connections or build alternative pathways as the brain recovers" from injury. Macmillan adds that if Gage made such a recovery—if he eventually "figured out how to live" (as Fleischman put it) despite his injury—then it "would add to current evidence that rehabilitation can be effective even in difficult and long-standing cases"; and if Gage could achieve such improvement without medical supervision, "what are the limits for those in formal rehabilitation programs?" As author Sam Kean put it, "If even Phineas Gage bounced back—that's a powerful message of hope."

Exaggeration and distortion of mental changes

A moral man, Phineas Gage— Anonymous

Tamping powder down holes for his wage

Blew his special-made probe

Through his left frontal lobe

Now he drinks, swears, and flies in a rage.

Macmillan's analysis of scientific and popular accounts of Gage found that they almost always distort and exaggerate his behavioral changes well beyond anything described by anyone who had direct contact with him, concluding that the known facts are "inconsistent with the common view of Gage as a boastful, brawling, foul-mouthed, dishonest useless drifter, unable to hold down a job, who died penniless in an institution". In the words of Barker, "As years passed, the case took on a life of its own, accruing novel additions to Gage's story without any factual basis". Even today (writes Zbigniew Kotowicz) "Most commentators still rely on hearsay and accept what others have said about Gage, namely, that after the accident he became a psychopath"; Grafman has written that "the details of [Gage's] social cognitive impairment have occasionally been inferred or even embellished to suit the enthusiasm of the story teller"; and Goldenberg calls Gage "a (nearly) blank sheet upon which authors can write stories which illustrate their theories and entertain the public".

For example, Harlow's statement that Gage "continued to work in various places; could not do much, changing often, and always finding something that did not suit him in every place he tried" refers only to Gage's final months, after convulsions had set in. But it has been misinterpreted as meaning that Gage never held a regular job after his accident, "was prone to quit in a capricious fit or be let go because of poor discipline", "never returned to a fully independent existence", "spent the rest of his life living miserably off the charity of others and traveling around the country as a sideshow freak", and ("dependent on his family" or "in the custody of his parents") died "in careless dissipation". In fact, after his initial post-recovery months spent traveling and exhibiting, Gage supported himself—at a total of two jobs—from early 1851 until just before his death in 1860.

Other behaviors ascribed to the post-accident Gage that are either unsupported by, or in contradiction to, the known facts include the following:

- mistreatment of wife and children (though Gage actually had neither);

- inappropriate sexual behavior, promiscuity, or impaired sexuality;

- lack of forethought, concern for the future, or capacity for embarrassment;

- parading his self-misery, and vainglory in showing his wounds;

- "gambling" himself into "emotional and reputational ... bankruptcy";

- irresponsibility, untrustworthiness, aggressiveness, violence;

- vagrancy, begging, drifting, drinking;

- lying, brawling, bullying;

- psychopathy, inability to make ethical decisions;

- loss of all respect for social conventions;

- acting like an "idiot" or a "lout";

- living as a "layabout" or a "boorish mess";

- "[alienating] almost everyone who had ever cared about him";

- dying "due to a debauch".

Nonetheless (write Daffner and Searl) "the telling of [Gage's] story has increased interest in understanding the enigmatic role that the frontal lobes play in behavior and personality", and Ratiu has said that in teaching about the frontal lobes, an anecdote about Gage is like an "ace [up] your sleeve. It's just like whenever you talk about the French Revolution you talk about the guillotine, because it's so cool." Benderly suggests that instructors use the Gage case to illustrate the importance of critical thinking.

Extent of brain damage

The left frontal lobe (red), with Ratiu et al.'s estimate of the tamping iron's path.

It is regretted that an autopsy could not have been had, so that the precise condition of the encephalon at the time of his death might have been known.

— J. M. Harlow (1868)

False-color representations of cerebral fiber pathways affected, per Van Horn et al.

In addition, Ratiu et al. noted that the hole in the base of the cranium (created as the tamping iron passed through the sphenoidal sinus into the brain) has a diameter about half that of the iron itself; combining this with the hairline fracture beginning behind the exit region and running down the front of the skull, they concluded that the skull "hinged" open as the iron entered from below, then was pulled closed by the resilience of soft tissues once the iron had exited through the top of the head.

Van Horn et al. concluded that damage to Gage's white matter (of which they made detailed estimates) was as or more significant to Gage's mental changes than cerebral cortex (gray matter) damage. Thiebaut de Schotten et al. estimated white-matter damage in Gage and two other famous patients ("Tan" and "H.M."), concluding that these three cases "suggest that social behavior, language, and memory depend on the coordinated activity of different [brain] regions rather than single areas in the frontal or temporal lobes."

Factors favoring Gage's survival

"I have the pleasure of being able to present to you [a case] without parallel in the annals of surgery." Harlow's 1868 presentation to the Massachusetts Medical Society of Gage's skull, tamping iron, and post-accident history.

Harlow saw Gage's survival as demonstrating "the wonderful resources of the system in enduring the shock and in overcoming the effects of so frightful a lesion, and as a beautiful display of the recuperative powers of nature", and listed what he saw as the circumstances favoring it:

1st. The subject was the man for the case. His physique, will, and capacity of endurance, could scarcely be excelled.For Harlow's description of the pre-accident Gage, see § Background, above.

2d. The shape of the missile—being pointed, round and comparatively smooth, not leaving behind it prolonged concussion or compression.Despite its very large diameter and mass (compared to a weapon-fired projectile) the tamping iron's relatively low velocity drastically reduced the energy available to compressive and concussive "shock waves".

Harlow continued:

3d. The point of entrance ... [The tamping iron] did little injury until it reached the floor of the cranium, when, at the same time that it did irreparable damage, it [created the] opening in the base of the skull, for drainage, [without which] recovery would have been impossible.Barker writes that "[Head injuries] from falls, horse kicks, and gunfire, were well known in pre–Civil War America [and] every contemporary course of lectures on surgery described the diagnosis and treatment" of such injuries. But to Gage's benefit, surgeon Joseph Pancoast had performed "his most celebrated operation for head injury before Harlow's medical class, [trepanning] to drain the pus, resulting in temporary recovery. Unfortunately, symptoms recurred and the patient died. At autopsy, reaccumulated pus was found: granulation tissue had blocked the opening in the dura." By keeping the exit wound open, and elevating Gage's head to encourage drainage from the cranium into the sinuses (through the hole made by the tamping iron), Harlow "had not repeated Professor Pancoast's mistake".

No attempt will be made by me to cite analogous cases, as after ransacking the literature of surgery in quest of such, I learn that all, or nearly all, soon came to a fatal result.— J. M. Harlow (1868)

Finally,

4th. The portion of the brain traversed was, for several reasons, the best fitted of any part of the cerebral substance to sustain the injury.Precisely what Harlow's "several reasons" were is unclear, but he was likely referring, at least in part, to the understanding (slowly developing since ancient times) that injuries to the front of the brain are less dangerous than those to the rear, because the latter frequently interrupt vital functions such as breathing and circulation. For example, surgeon James Earle wrote in 1790 that "a great part of the cerebrum may be taken away without destroying the animal, or even depriving it of its faculties, whereas the cerebellum will scarcely admit the smallest injury, without being followed by mortal symptoms."

Harlow's 1868 paper on Gage was widely reported. This item appeared in Scientific American for July, 1868.

Ratiu et al. and Van Horn et al. both concluded that the superior sagittal sinus must have remained intact, both because Harlow does not mention loss of cerebrospinal fluid through the nose, and because otherwise Gage would almost certainly have suffered fatal blood loss or air embolism. Harlow's moderate (in the context of medical practice of the time) use of emetics, purgatives, and (in one instance) bleeding would have "produced dehydration with reduction of intracranial pressure [which] may have favorably influenced the outcome of the case", according to Steegmann.

As to his own role in Gage's survival, Harlow merely averred, "I can only say ... with good old Ambroise Paré, I dressed him, God healed him", but Macmillan calls this self-assessment far too modest. Noting that Harlow had been a "relatively inexperienced local physician ... graduated four and a half years earlier", Macmillan's discussion of Harlow's "skillful and imaginative adaptation [of] conservative and progressive elements from the available therapies to the particular needs posed by Gage's injuries" emphasizes that he "did not apply rigidly what he had learned", for example foregoing an exhaustive search for bone fragments (which risked hemorrhage and further brain injury) and applying caustic to the "fungi" instead of excising it (which risked hemorrhage) or forcing it into the wound (which risked compressing the brain).

Early medical attitudes

Skepticism

The very small amount

of attention that has been given to [this] case can only be explained

by the fact that it far transcends any case of recovery from injury

of the head that can be found in the records of surgery. It was too

monstrous for belief ...

— J. B. S. Jackson (1870)

Boston Herald, 1907

Barker notes that Harlow's original 1848 report of Gage's survival and recovery "was widely disbelieved, for obvious reasons" and Harlow, in his 1868 retrospective, recalled this early skepticism:

The case occurred nearly twenty years ago, in an obscure country town ..., was attended and reported by an obscure country physician, and was received by the Metropolitan Doctors with several grains of caution, insomuch that many utterly refused to believe that the man had risen, until they had thrust their fingers into the hole [in] his head, and even then they required of the Country Doctor attested statements, from clergymen and lawyers, before they could or would believe—many eminent surgeons regarding such an occurrence as a physiological impossibility, the appearances presented by the subject being variously explained away."A distinguished Professor of Surgery in a distant city", Harlow continued, had even dismissed Gage as a "Yankee invention".

According to the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (1869) it was the 1850 report on Gage by Bigelow—Harvard's Professor of Surgery and "a majestic and authoritative figure on the medical scene of those times" —that "finally succeeded in forcing [the case's] authenticity upon the credence of the profession ... as could hardly have been done by any one in whose sagacity and surgical knowledge his confrères had any less confidence". Noting that, "The leading feature of this case is its improbability ... This is the sort of accident that happens in the pantomime at the theater, not elsewhere", Bigelow emphasized that though "at first wholly skeptical, I have been personally convinced".

Nonetheless (Bigelow wrote just before Harlow's 1868 presentation of Gage's skull) though "the nature of [Gage's] injury and its reality are now beyond doubt ... I have received a letter within a month [purporting] to prove that ... the accident could not have happened."

Standard for other brain injuries

"[Few objects] have attracted more visitors and spread farther the fame of the Museum"

As the reality of Gage's accident and survival gained credence, it became "the standard against which other injuries to the brain were judged", and it has retained that status despite competition from a growing list of other unlikely-sounding brain-injury accidents, including encounters with axes, bolts, low bridges, exploding firearms, a revolver shot to the nose, other tamping irons, and falling Eucalyptus branches. For example, after a miner survived traversal of his skull by a gas pipe 5⁄8 inch (1.6 cm) in diameter (extracted "not without considerable difficulty and force, owing to a bend in the portion of the rod in his skull") his physician invoked Gage as the "only case comparable with this, in the amount of brain injury, that I have seen reported".

Often these comparisons carried hints of humor, competitiveness, or both. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, for example, termed Gage "the patient whose cerebral organism had been comparatively so little disturbed by its abrupt and intrusive visitor"; and a Kentucky doctor, reporting a patient's survival of a gunshot through the nose, bragged, "If you Yankees can send a tamping bar through a fellow's brain and not kill him, I guess there are not many can shoot a bullet between a man's mouth and his brains, stopping just short of the medulla oblongata, and not touch either." Similarly, when a lumbermill foreman returned to work soon after a saw cut three inches (8 cm) into his skull from just between the eyes to behind the top of his head, his surgeon (who had removed from this wound "thirty-two pieces of bone, together with considerable sawdust") termed the case "second to none reported, save the famous tamping-iron case of Dr. Harlow", though apologizing that "I cannot well gratify the desire of my professional brethren to possess [the patient's] skull, until he has no further use for it himself."

As these and other remarkable brain-injury survivals accumulated, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal pretended to wonder whether the brain has any function at all: "Since the antics of iron bars, gas pipes, and the like skepticism is discomfitted, and dares not utter itself. Brains do not seem to be of much account now-a-days." The Transactions of the Vermont Medical Society was similarly facetious: "'The times have been,' says Macbeth [Act III], 'that when the brains were out the man would die. But now they rise again.' Quite possibly we shall soon hear that some German professor is exsecting it."

Theoretical misuse

The Gage who appears in contemporary psychology textbooks is simply a compound creature ... a stunning example of the ideological uses of case histories and their mythological reconstruction.

— Rhodri Hayward

Though Gage is considered the "index case for personality change due to frontal lobe damage",

Cerebral localization

In the nineteenth-century debate over whether the various mental functions are or are not localized in specific regions of the brain , both sides managed to enlist Gage in support of their theories. For example, after Dupuy wrote that Gage proved that the brain is not localized (characterizing him as a "striking case of destruction of the so-called speech centre without consequent aphasia") Ferrier made a "devastating reply" in his 1878 Goulstonian Lectures, "On the Localisation of Cerebral Disease", of which Gage (along with the woodcuts of his skull and tamping iron from Harlow's 1868 paper) was "an absolutely dominating feature".Phrenology

Phrenologists

contended that destruction of the mental "organs" of Veneration and

Benevolence caused Gage's behavioral changes. Harlow may have believed

that the Organ of Comparison was damaged as well.

Throughout the nineteenth century, adherents of phrenology contended that Gage's mental changes (his profanity, for example) stemmed from destruction of his mental "organ of Benevolence"—as phrenologists saw it, the part of the brain responsible for "goodness, benevolence, the gentle character ... [and] to dispose man to conduct himself in a manner conformed to the maintenance of social order"—and/or the adjacent "organ of Veneration"—related to religion and God, and respect for peers and those in authority. (Phrenology held that the organs of the "grosser and more animal passions are near the base of the brain; literally the lowest and nearest the animal man [while] highest and farthest from the sensual are the moral and religions feelings, as if to be nearest heaven". Thus Veneration and Benevolence are at the apex of the skull—the region of exit of Gage's tamping iron.)

Harlow wrote that Gage, during his convalescence, did not "estimate size or money accurately[,] would not take $1000 for a few pebbles" and was not particular about prices when visiting a local store; by these examples Harlow may have been implying damage to phrenology's "Organ of Comparison".

Psychosurgery and lobotomy

It is frequently asserted that what happened to Gage played a role in the later development of various forms of psychosurgery—particularly lobotomy—or even that Gage's accident constituted "the first lobotomy". Aside from the question of why the unpleasant changes usually (if hyperbolically) attributed to Gage would inspire surgical imitation, there is no such link, according to Macmillan:There is simply no evidence that any of these operations were deliberately designed to produce the kinds of changes in Gage that were caused by his accident, nor that knowledge of Gage's fate formed part of the rationale for them ... [W]hat his case did show came solely from his surviving his accident: major operations [such as for tumors] could be performed on the brain without the outcome necessarily being fatal.

Somatic marker hypothesis

Memorial plaque, Cavendish, Vermont

Antonio Damasio, in support of his somatic marker hypothesis (relating decision-making to emotions and their biological underpinnings), draws parallels between behaviors he ascribes to Gage and those of modern patients with damage to the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala. But Damasio's depiction of Gage has been severely criticized, for example by Kotowicz:

Damasio is the principal perpetrator of the myth of Gage the psychopath ... Damasio changes [Harlow's] narrative, omits facts, and adds freely ... His account of Gage's last months [is] a grotesque fabrication [insinuating] that Gage was some riff-raff who in his final days headed for California to drink and brawl himself to death ... It seems that the growing commitment to the frontal lobe doctrine of emotions brought Gage to the limelight and shapes how he is described.As Kihlstrom put it, "[M]any modern commentators exaggerate the extent of Gage's personality change, perhaps engaging in a kind of retrospective reconstruction based on what we now know, or think we do, about the role of the frontal cortex in self-regulation." Macmillan gives detailed criticism of Antonio Damasio's various presentations of Gage (some of which are joint work with Hannah Damasio and others).

Portraits

Inscription on iron as seen in portrait detail: ... [Phine]has P. Gage at Cavendish, Vermont, Sept. 14, 1848. He fully ...

The second portrait of Gage identified (2010)

Two daguerreotype portraits of Gage, identified in 2009 and 2010, are the only likenesses of him known other than a plaster head cast taken for Bigelow in late 1849 (and now in the Warren Museum along with Gage's skull and tamping iron). The first shows a "disfigured yet still-handsome" Gage with left eye closed and scars clearly visible, "well dressed and confident, even proud" and holding his iron, on which portions of its inscription can be made out. (For decades the portrait's owners had believed that it depicted an injured whaler with his harpoon.) The second, copies of which are in the possession of two branches of the Gage family, shows Gage in a somewhat different pose wearing the same waistcoat and possibly the same jacket, but with a different shirt and tie.

Authenticity was confirmed by photo-overlaying the inscription on the tamping iron, as seen in the portraits, against that on the actual tamping iron, and matching the subject's injuries to those preserved in the head cast. However, about when, where, and by whom the portraits were taken nothing is known, except that they were created no earlier than January 1850 (when the inscription was added to the tamping iron), on different occasions, and are likely by different photographers.

The portraits support other evidence that Gage's most serious mental changes were temporary . "That [Gage] was any form of vagrant following his injury is belied by these remarkable images", wrote Van Horn et al. "Although just one picture," Kean commented in reference to the first image discovered, "it exploded the common image of Gage as a dirty, disheveled misfit. This Phineas was proud, well-dressed, and disarmingly handsome."