| African elephant | |

|---|---|

| |

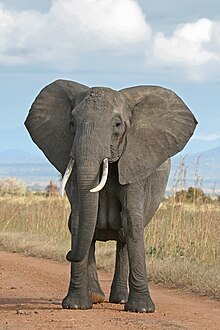

| African bush elephant, Loxodonta africana, in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

| |

| Female African forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis, with juvenile, Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, Republic of the Congo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Subfamily: | Elephantinae |

| Genus: | Loxodonta Anonymous, 1827 |

| Species | |

|

L. adaurora †

L. africana L. atlantica † L. cyclotis L. exoptata † | |

| |

| Distribution of Loxodonta (2007) | |

African elephants are elephants of the genus Loxodonta. The genus consists of two extant species: the African bush elephant, L. africana, and the smaller African forest elephant, L. cyclotis. Loxodonta (from Greek λοξός, loxós: 'slanting, crosswise, oblique sided' + ὀδούς, odoús: stem odónt-, 'tooth') is one of two existing genera of the family Elephantidae. Fossil remains of Loxodonta have been found only in Africa, in strata as old as the middle Pliocene. However, sequence analysis of DNA extracted from fossils of the extinct straight-tusked elephant undermines the validity of the genus.

Description

One

species of African elephant, the bush elephant, is the largest living

terrestrial animal, while the forest elephant is the third-largest.

Their thickset bodies rest on stocky legs, and they have concave backs. Their large ears enable heat loss. The upper lip and nose form a trunk.

The trunk acts as a fifth limb, a sound amplifier, and an important

method of touch. African elephants' trunks end in two opposing lips, whereas the Asian elephant trunk ends in a single lip. In L. africana,

males stand 3.2–4.0 m (10.5–13.1 ft) tall at the shoulder and weigh

4,700–6,048 kg (10,362–13,334 lb), while females stand 2.2–2.6 m

(7.2–8.5 ft) tall and weigh 2,160–3,232 kg (4,762–7,125 lb); L. cyclotis is smaller with male shoulder heights of up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft).

The largest recorded individual stood 3.96 m (13.0 ft) at the shoulder

and weighed 10.4 tonnes (10.2 long tons; 11.5 short tons). The tallest recorded individual stood 4.21 m (13.8 ft) at the shoulder and weighed 8 tonnes (7.9 long tons; 8.8 short tons).

Teeth

Elephants have four molars;

each weighs about 5 kg (11 lb) and measures about 30 cm (12 in) long.

As the front pair wears down and drops out in pieces, the back pair

moves forward, and two new molars emerge in the back of the mouth.

Elephants replace their teeth four to six times in their lifetimes.

Around 40 to 60 years of age, the elephant loses the last of its molars

and will likely die of starvation, a common cause of death. African

elephants have 24 teeth in total, six on each quadrant of the jaw. The enamel plates of the molars are fewer in number than in Asian elephants.

The elephants' tusks are firm teeth; the second set of incisors

become the tusks. They are used for digging for roots and stripping the

bark from trees for food, for fighting each other during mating season,

and for defending themselves against predators. The tusks weigh from

23–45 kg (51–99 lb) and can be from 1.5–2.4 m (5–8 ft) long. Unlike

Asian elephants, both male and female African elephants have tusks. They are curved forward and continue to grow throughout the elephant's lifetime.

A male African bush elephant skull on display at the Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma,USA

A female African bush elephant skeleton on display at the Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City

Distribution and habitat

African elephants are found widely in Sub-Saharan Africa, in dense forests, mopane and miombo woodlands, Sahelian scrub, or deserts.

Classification

In 1825, Georges Cuvier named the genus "Loxodonte". An anonymous author romanized the spelling to "Loxodonta", and the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature recognizes this as the proper authority.

- African bush elephant, Loxodonta africana

- † North African elephant, Loxodonta africana pharaoensis (extinct subspecies presumed to have existed north of the Sahara from the Atlas Mountains to Ethiopia)

- African forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis

- † Loxodonta atlantica (fossil), presumed ancestor of the modern African elephants

- † Loxodonta exoptata (fossil), presumed ancestor of L. atlantica

- † ? Loxodonta adaurora (fossil), may belong in Mammuthus

Female bush elephants in Tanzania: Females usually live in herds.

Bush and forest elephants were formerly considered subspecies of Loxodonta africana. As described in the entry for the forest elephant in the third edition of Mammal Species of the World (MSW3), there is morphological and genetic evidence that they should be considered as separate species.

Comparison of bush (left) and forest (right) elephant skulls in frontal view.

Note the shorter and wider head of L. cyclotis, with a concave instead of convex forehead.

Note the shorter and wider head of L. cyclotis, with a concave instead of convex forehead.

Much of the evidence cited in MSW3 is morphological. The

African forest elephant has a longer and narrower mandible, rounder

ears, a different number of toenails, straighter and downward tusks, and

considerably smaller size. With regard to the number of toenails: the

African bush elephant normally has four toenails on the front foot and

three on the hind feet, the African forest elephant normally has five

toenails on the front foot and four on the hind foot, but hybrids between the two species commonly occur.

MSW3 lists the two forms as full species and does not list any subspecies in its entry for Loxodonta africana. However, this approach is not taken by the United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Centre nor by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), both of which list L. cyclotis as a synonym (not even a subspecies) of L. africana. A consequence of the IUCN taking this view is that the IUCN Red List

makes no independent assessment of the conservation status of the two

forms of African elephant. It merely assesses the two forms taken

together, as vulnerable.

A study of nuclear DNA sequences,

published in 2010, indicated that the divergence date between forest

and savanna elephants was 2.6 – 5.6 million years ago, similar to the

divergence date estimated for the Asian elephant and the woolly mammoths

(2.5 – 5.4 million years ago), which strongly supports their status as

separate species. Forest elephants were found to have a high degree of

genetic diversity, perhaps reflecting periodic fragmentation of their

habitat during the climatic changes of the Pleistocene.

However, recent DNA sequence analysis indicates that the extinct European straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, is closer to L. cyclotis than L. cyclotis is to L. africana, thus invalidating Loxodonta as currently recognized.

Behavior

African

elephant societies are arranged around family units. Each family unit

is made up of around ten closely related females and their calves and is

led by an older female known as the matriarch. When separate family units bond, they form kinship or bond groups. After puberty,

male elephants tend to form close alliances with other males. While

females are the most active members of African elephant societies, both

male and female elephants are capable of distinguishing between hundreds

of different low frequency infrasonic calls to communicate with and identify each other.

Elephants are at their most fertile between the ages of 25 and 45. Calves are born after a gestation

period of up to nearly two years. The calves are cared for by their

mother and other young females in the group, known as allomothers.

Elephants use some vocalisations that are beyond the hearing range of humans, to communicate across large distances. Elephant mating rituals include the gentle entwining of trunks.

Feeding

While

feeding, elephants use their trunks to pluck at leaves and their tusks

to tear at branches, which can cause enormous damage to foliage.

A herd may deplete an area of foliage depriving other herbivores for a

time. African elephants may eat up to 450 kg (992 lb) of vegetation per

day, although their digestive system is not very efficient; only 40% of

this food is properly digested. The foregut fermentation used by ruminants is generally considered more efficient than the hindgut fermentation employed by proboscideans and perissodactyls;

however, the ability to process food more rapidly than foregut

fermenters gives hindgut fermenters an advantage at very large body

size, as they are able to accommodate significantly larger food intakes.

Intelligence

Scratching on a tree helps to remove layers of dead skin and parasites

African elephants are highly intelligent, and they have a very large and highly convoluted neocortex, a trait they share with humans, apes and some dolphin species. They are amongst the world's most intelligent species. With a mass of just over 5 kg (11 lb), elephant brains are larger than those of any other land animal, and although the largest whales have body masses twentyfold those of a typical elephant,

whale brains are barely twice the mass of an elephant's brain. The

elephant's brain is similar to that of humans in terms of structure and

complexity. For example, the elephant's cortex has as many neurons as that of a human brain, suggesting convergent evolution.

Elephants exhibit a wide variety of behaviors, including those associated with grief, learning, allomothering, mimicry, art, play, a sense of humor, altruism, use of tools, compassion, cooperation, self-awareness, memory and possibly language. All point to a highly intelligent species that is thought to be equal with cetaceans, and primates.

Reproduction

Bull elephants in mock aggression.

African elephants show sexual dimorphism

in weight and shoulder height by age 20, due to the rapid early growth

of males. By age 25, males are double the weight of females; however,

both sexes continue to grow throughout their lives.

Female African elephants are able to start reproducing at around 10 to 12 years of age,

and are in estrus for about 2 to 7 days. They do not mate at a specific

time; however, they are less likely to reproduce in times of drought

than when water is plentiful. The gestation period of an elephant is 22

months and fertile females usually give birth every 3 – 6 years, so if

they live to around 50 years of age, they may produce 7 offspring.

Females are a scarce and mobile resource for the males so there is

intense competition to gain access to estrous females.

Post sexual maturity, males begin to experience musth, a physical

and behavioral condition that is characterized by elevated

testosterone, aggression and more sexual activity.

Musth also serves a purpose of calling attention to the females that

they are of good quality, and it cannot be mimicked as certain calls or

noises may be. Males sire few offspring in periods when they are not in

musth. During the middle of estrus, female elephants look for males in

musth to guard them. The females will yell, in a loud, low way to

attract males from far away. Male elephants can also smell the hormones

of a female ready for breeding. This leads males to compete with each

other to mate, which results in the females mating with older, healthier

males.

Females choose to a point who they mate with, since they are the ones

who try to get males to compete to guard them. However, females are not

guarded in the early and late stages of estrus, which may permit mating

by younger males not in musth.

Males over the age of 25 compete strongly for females in estrous,

and are more successful the larger and more aggressive they are. Bigger males tend to sire bigger offspring.

Wild males begin breeding in their thirties when they are at a size and

weight that is competitive with other adult males. Male reproductive

success is maximal in mid-adulthood and then begins to decline. However,

this can depend on the ranking of the male within their group, as

higher-ranking males maintain a higher rate of reproduction.

Most observed matings are by males in musth over 35 years of age.

Twenty-two long observations showed that age and musth are extremely

important factors; "… older males had markedly elevated paternity

success compared with younger males, suggesting the possibility of

sexual selection for longevity in this species." (Hollister-Smith, et

al. 287).

Males usually stay with a female and her herd for about a month

before moving on in search for another mate. Less than a third of the

population of female elephants will be in estrus at any given time and

gestation period of an elephant is long, so it makes more evolutionary

sense for a male to search for as many females as possible rather than

stay with one group.

Gallery

The following sequence of five images was taken in the Addo Elephant Park in South Africa.

- Elephant mating ritual

Mating in captivity

African elephants mating in Tierpark Berlin

The social behavior of elephants in captivity mimics that of those in

the wild. Females are kept with other females, in groups, while males

tend to be separated from their mothers at a young age, and are kept

apart. According to Schulte, in the 1990s, in North America, a few

facilities allowed male interaction. Elsewhere, males were only allowed

to smell each other. Males and females were allowed to interact for

specific purposes such as breeding. In that event, females were more

often moved to the male than the male to the female. Females are more

often kept in captivity because they are easier and less expensive to

house.

Conservation

Men with African elephant tusks, Dar es Salaam, c. 1900

Population estimates and poaching

During the 20th century, poaching significantly reduced the population of Loxodonta in some regions. The World Wide Fund for Nature believes there were between 3 and 5 million African elephants as recently as the 1930s and 1940s. Between 1980 and 1990 the population of African elephants was more than halved, from 1.3 million to around 600,000. Between 1973 and 1989, the African elephant population of Kenya declined by 85%. In Chad, the population declined from 400,000 in 1970 to about 10,000 in 2006. The population in the Tanzanian Selous Game Reserve, once the largest of any reserve in the world, dropped from 109,000 in 1976 to 13,000 in 2013.

The government of Tanzania estimated that more than 85,000 elephants

were lost to poaching in Tanzania between 2009 and 2014, representing a

60% loss.

In 1989, CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) banned international trade in ivory

to fight this massive illegal trade. After the ban came into force in

1990, major ivory markets were eliminated. As a result, African elephant

populations experienced a decline in illegal killing, particularly

where they were appropriately protected. This allowed some elephant

populations to recover. Nevertheless, within countries where wildlife

management authorities are greatly under-funded, poaching is still a

significant problem.

The World Wildlife Foundation

states that the two threats that impact African elephants the most are

the demand for ivory and changes in land usage. The majority of the

ivory leaving Africa continues to be acquired and transported illegally,

and over 80% of all the raw ivory traded comes from poached African

elephants. From 2006 to 2012 the magnitude of poaching increased

(including some 3,000 elephants slaughtered in between 2006 and 2009).

In an incident lasting a few days in February 2012 in Bouba N'Djida park

in Cameroon, 650 elephants were poached. In early March 2013 in Chad,

86 elephants — including 33 pregnant females — were killed in "a

potentially devastating blow to one of central Africa's last remaining

elephant populations."

By 2014 it was estimated that only 50,000 elephants remained in Central

Africa. The last major populations are present in Gabon and the

Republic of Congo.

According to the World Wildlife Fund,

in 2014 the total population of African elephants was estimated to be

around 700,000, and the Asian elephant population was estimated to be

around 32,000. The population of African elephants in Southern Africa is

large and expanding, with more than 300,000 within the region; Botswana

has 200,000 and Zimbabwe 80,000. Large populations of elephants are

confined to well-protected areas. However, conservative estimates were

that 23,000 African elephants were killed by poachers in 2013 and less than 20% of the African elephant range was under formal protection.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature released a report in

September 2016 that estimates Africa's elephant population at 415,000.

They reported that in the past decade, this is a decline of 111,000

elephants. This is reported as the worst decline in the past 25 years.

Between the African elephants and the Asian elephants there is a

large variance in genetics; also, within Africa the different species

vary in genetics based on where they live. The two African species, Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis, share different gene flow and have limited hybridization with each other.

When examining the gene flow between the forest and savanna

elephants, observers look at 21 distinct locations. The evidence points

to the fact that there was ancient hybridization since the species

share a small amount of similar DNA.

Legal protection and conservation status

Protection

of African elephants is a high-profile conservation cause in many

countries. In 1989, the Kenyan Wildlife Service burned a stockpile of

tusks in protest against the ivory trade. However, African elephant populations can be devastated by poaching despite nominal governmental protection, and some nations permit the hunting of elephants for sport. In 2012, The New York Times reported a large upsurge in ivory poaching, with about 70% of the product flowing to China.

Conflicts between elephants and a growing human population are a major issue in elephant conservation.

Human encroachment into natural areas where bush elephants occur or

their increasing presence in adjacent areas has spurred research into

methods of safely driving groups of elephants away from humans. Playback

of the recorded sounds of angry honey bees has been found to be remarkably effective at prompting elephants to flee an area. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) African elephant specialist group has set up a human-elephant conflict

working group. They believe that different approaches are needed in

different countries and regions, and so develop conservation strategies

at national and regional levels.

Under the auspices of the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, a Memorandum of Understanding concerning Conservation Measures for the West African Populations of the African Elephant came into effect on 22 November 2005. The MoU

aims to protect the West African elephant population by providing an

international framework for state governments, scientists and

conservation groups to collaborate in the conservation of the species

and its habitat.

China was the biggest market for poached ivory but announced that

it would phase out the legal domestic manufacture and sale of ivory

products in May 2015, and in September of that year, China and the

U.S.A. "said they would enact a nearly complete ban on the import and

export of ivory."

In response Chinese consumers moved to purchasing their ivory through

markets in Laos, leading conservation groups to request pressure be put

on Laos to end the trade.