| |

| Founded | 2007 (as a project of the Center for the Expansion of Fundamental Rights), officially renamed NhRP 2012 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Steven Wise |

| Type | 501(c)(3) |

| Focus | Animal rights |

| Location | |

Area served

| United States |

| Method | Sustained strategic litigation |

Key people

| Steven M. Wise, Jane Goodall, Kevin Schneider, Elizabeth Stein, Monica Miller, Michael Mountain |

| Website | www |

The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) is an American animal rights nonprofit organization seeking to change the legal status of at least some nonhuman animals from that of property to that of persons, with a goal of securing rights to bodily liberty (the right not to be imprisoned) and bodily integrity (the right not to be experimented on). The NhRP works largely through state-by-state litigation in what it determines to be the most appropriate common law jurisdictions and bases its arguments on existing scientific evidence concerning self-awareness and autonomy in nonhuman animals. Its sustained strategic litigation campaign has been developed primarily by a team of attorneys, legal experts, and volunteer law students who have conducted extensive research into relevant legal precedents. The NhRP filed its first lawsuits in December 2013 on behalf of four chimpanzees held in captivity in New York State. In late 2014, NhRP President Steven Wise and Executive Director Natalie Prosin announced in the Global Journal of Animal Law that the Nonhuman Rights Project was expanding its work into other countries, beginning in Switzerland, Argentina, England, Spain, Portugal, and Australia.

The Nonhuman Rights Project is currently one of Animal Charity Evaluators' Standout Charities.

History

Founded by attorney Steven M. Wise, the Nonhuman Rights Project began in 2007 as a project of the Center for the Expansion of Fundamental Rights. In 2012, the Center for the Expansion of Fundamental Rights officially changed its name to the Nonhuman Rights Project.

Mission and goals

According

to the NhRP's website, the mission of the Nonhuman Rights Project is,

through education and litigation, to change the common law status of at

least some nonhuman animals from mere "things," which lack the capacity

to possess any legal right, to "persons," who possess such fundamental

rights as bodily integrity and bodily liberty and those other legal

rights to which evolving standards of morality, scientific discovery,

and human experience entitle them. To advance this mission, the NhRP's

specific goals are:

- To persuade a United States state high court to declare that a specific nonhuman animal is a legal person who possesses the capacity for a specific legal right.

- To persuade US state high courts to increase the number of legal rights of any nonhuman animal who is declared to be a legal person to the degree to which it should be entitled.

- To persuade US state high courts to declare that appropriate nonhuman animals possess the capacities for legal rights and to extend legal rights to them accordingly.

- To educate the legal profession and judiciary about the legal, social, historical and political justice of the Nonhuman Rights Project's arguments.

- To communicate to the public and media the NhRP's mission and the justice of recognizing specific nonhuman animals as legal persons.

- To educate the courts, the legal profession, the media, and the public about the state of current knowledge about the cognition of those nonhuman animals who are, or who might be, plaintiffs in the Nonhuman Rights Project's lawsuits.

Legal claims

The NhRP argues that nonhuman animals who are scientifically proven to be self-aware, autonomous beings, such as great apes, elephants, dolphins, and whales, should be recognized as legal persons under U.S. common law, with the fundamental right to bodily liberty.

According to the NhRP, there is nothing in the common law that suggests

that legal personhood is limited only to human beings, and certain

species fit the profile that courts have used in the past to recognize

legal personhood. The NhRP emphasizes the fact that currently all

nonhuman animals are considered merely property, or legal "things,"

without the capacity for rights. In an article published five months before the NhRP first filed suit, Chris Berdick of Boston Globe explains the organization's claims and strategy as follows:

Armed with affidavits from scientists, including Jane Goodall, about chimps' capacities, [the NhRP] will argue that their plaintiff deserves a right to liberty, and that its captivity is a violation of that right. Win or lose, they plan to bring more habeas petitions on behalf of other animals, hoping to win enough small victories to lay a foundation of precedent for animal personhood. It's unlikely to be a quick and easy fight, but Wise says he accepts that he's in the animal-personhood game for the long haul. "This is a long-term, strategic, open-ended campaign," he says.

Somerset v. Stewart

The NhRP's legal claims on behalf of captive nonhuman animals are based in part on the case of Somerset v Stewart. In that 1772 case, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, the chief justice of the English Court of King's Bench, issued a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of a slave named James Somerset;

Somerset was subsequently freed. NhRP argues that it was the first time

a human slave was considered to be a person and who was allowed to

petition for and be granted the writ for habeas corpus.

The decision was made even though there was no precedent that it relied

on. The NhRP views the writ of habeas corpus as a powerful form of

redress for the denial of their plaintiffs' right to bodily liberty.

Commenting on the importance of the Somerset case to the NhRP in a 2014

article by Charles Siebert in The New York Times Magazine, Wise said:

A legal person is not synonymous with a human being. A legal person is an entity that the legal system considers important enough so that it is visible and [has] interests [and] certain kinds of rights. I often ask my students: 'You tell me, why should a human have fundamental rights?' There's not a single person on earth I've ever put that question to who can answer that without referring to certain qualities that a human has.

Opposition and counterarguments

Some legal scholars have publicly opposed the NhRP's mission and goals. Federal appeals judge Richard Posner,

for example, is opposed to legal personhood for nonhuman animals on the

basis that the law grants humans special status not because of their

intelligence but out of "a moral intuition deeper than any reason that

could be given for it and impervious to any reason that you or anyone

could give against it." Attorney and Pepperdine Professor of Law Richard Cupp has argued that animal welfare

laws should be sufficient for ensuring the well-being of captive

nonhuman animals and that the NhRP's strategy is unnecessarily extreme.

In an interview with the James Gorman of The New York Times

following the organization's first lawsuits, Cupp said, "The courts

would have to dramatically expand existing common law for the cases to

succeed."

In response, the NhRP argues that an animal welfare approach is

insufficient and ineffective in terms of ending the practice of keeping

chimpanzees and other cognitively complex nonhuman animals in captivity

and also does nothing to address the larger issue of their status as

legal property.

Court cases

Tommy, Kiko, and Hercules and Leo

The

NhRP filed its first lawsuits on December 2, 2013, in New York State on

behalf of four captive chimpanzees, demanding that the courts grant

them the right to bodily liberty via the writ of habeas corpus and to

immediately send them to a sanctuary affiliated with the North American

Primate Sanctuary Alliance.

The NhRP's New York plaintiffs were Tommy, a privately owned

chimpanzee living in a cage in a shed on a used trailer lot in

Gloversville, NY; Kiko, a privately owned chimpanzee living on private

property in Niagara Falls, NY; and Hercules and Leo, two chimpanzees

owned by New Iberia Research Center and loaned to the Anatomy Department

at Stony Brook University for use in locomotion research.

In response to the lawsuit, Tommy's owner, Patrick Lavery, defended the

chimpanzee's living conditions: "He's really got it good. He's got a

lot of enrichment. He's got color TV, cable and a stereo."

All of the petitions were rejected. On March 19, 2015 case of Hercules and Leo was refiled. And on April 20, 2015, Justice Barbra Jaffe issued an Order to Show Cause and Writ of Habeas Corpus.

A hearing was scheduled at which the State University of New York at

Stoney Brook was ordered to show why Hercules and Leo should be not be

released and transferred to the Save the Chimps sanctuary.

Because the order's title included the phrase "WRIT TO HABEAS CORPUS"

it made headlines around the world and was misinterpreted as granting

the right to liberty to a chimpanzee. Justice Jaffe's order was amended and refiled with the phrase WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS manually crossed out. A hearing was held on May 27 and on July 29, 2015, Justice Jaffe issued an order denying Hercules and Leo's petition.

Because of the fact that the petition was reviewed as well as the

reasoning in the decision, NhRP considered it to be a "one giant leap

for the Nonhuman Rights Project in its fight for the fundamental rights

of nonhuman animals."

Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

In filing the petitions NhRP's intent was:

- To have the chimpanzees recognized as human-like beings with a common law right to liberty, specifically, to be recognized as autonomous and self-determining beings that cannot be legally considered as property. and

- To have the chimpanzees released and transferred to a North American Primate Sanctuary Alliance (NAPSA) sanctuary.

A writ of habeas corpus

allows an individual to assert one's right to liberty and demand for

release from unlawful imprisonment. The right to file the writ is

protected in the US Constitution under Article 1, Section 9, and in New

York State it is to be filed under article 70 which states that "a person

illegally imprisoned or otherwise restrained with his liberty within

the state ... may petition without notice for a writ of habeas corpus to

inquire into the cause of such detention and for deliverance." In order

for their petitions to be considered, NhRP had to first show that the

chimpanzees are persons who could file them.

NhRP's arguments were partially based on precedent, a legal term that encompasses all previous legal decisions and reasoning also known as common law. These cases can be considered to be relevant and sometimes decisive to the current facts and circumstances at hand. As its first step, NhRP argued that the legal term person is

not a synonym for a human being, but instead refers to an entity with a

capacity to possess legal rights. It emphasized that there are no

necessary conditions for determining that an entity is a legal person,

and that going back to the 18th century there have been cases granting

legal rights to non human entities such as corporations. NhRP argued

that the fact that a chimpanzee is not a human being should not prevent

the argument that it is a legal person with a habeas corpus right to

liberty.

It then made its central point, that based on previous common law decisions such as Somerset v Stewart,

autonomy and self-determination are the human qualities that are

intended to be protected by the writ of habeas corpus. And because

chimpanzees are now known to possesses the same qualities, the habeas

corpus right to liberty should be expanded to the chimpanzee species.

More than thirty pages of the petition were devoted to going over

chimpanzee evolutionary development, neurology, social practices and

complex cognition. NhRP argued that a chimpanzee possesses qualities

such as:

... the possession of an autobiographical self, episodic memory, self-determination, self-consciousness, self-knowing, self-agency, referential and intentional communication, empathy, a working memory, language, metacognition, numerosity, and material, social and symbolic culture, their ability to plan, engage in mental time travel, intentional action, sequential learning, mediational learning, mental state modeling, visual perspective-taking, cross-modal perception, their ability to understand cause-and-effect, the experiences of others, to imagine, imitate, engage in deferred imitation, emulate, to innovate and to make and use tools.

NhRP emphasized that it was not seeking a granting of human rights

for its plaintiffs but only a narrow expansion of the right to bodily

liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus.

Initial holdings

All

three petitions where denied on the grounds that the chimpanzees were

not persons and thus the issues in the petitions would not be

considered. In an hour long hearing regarding Tommy's Third District case, the Hon. Joseph Sise stated that:

Your impassioned representations to the Court are quite impressive. The Court will not entertain the application, will not recognize a chimpanzee as a human or as a person who can seek a writ of habeas corpus under Article 70. I will be available as the judge for any other lawsuit to right any wrongs that are done to this chimpanzee because I understand what you're saying. You make a very strong argument. However, I do not agree with the argument only insofar as Article 70 applies to chimpanzees. Good luck with your venture. I'm sorry I can't sign the order, but I hope you continue. As an animal lover, I appreciate your work.

The judge in Kiko's Fourth district case, the Hon. Ralph A. Boniello

III, also held a hearing, denying the NhRP's petition on the grounds

that Kiko is not a person for purposes of habeas corpus and stating that

he did not want to be the first "to make that leap of faith."

The judge in Hercules' and Leo's Second District case, the Hon. W.

Gerard Asher, did not hold a hearing, writing in a decision that he was

denying the petition for habeas corpus on the basis that chimpanzees are

not considered legal persons.

Appeals

Tommy's case

The NhRP appealed the lower court's decision in Tommy's case.

The appeal was granted and oral argument took place on October 8, 2014

before the Supreme Court, Appellate Division, Third Judicial Department

in Albany, NY. The hearing received significant media attention. On December 5, 2014, the appellate court issued its ruling. In

its decision the court confirmed the earlier ruling that there is no

precedent for finding that an animal could be thought of as a person. It

further reasoned that in accordance with the social contract one's

rights cannot come without obligations:

The lack of precedent for treating animals as persons for habeas corpus purposes does not, however, end the inquiry, as the writ has over time gained increasing use given its great flexibility and vague scope. While petitioner proffers various justifications for affording chimpanzees, such as Tommy, the liberty rights protected by such writ, the ascription of rights has historically been connected with the imposition of societal obligations and duties. Reciprocity between rights and responsibilities stems from principles of social contract, which inspired the ideals of freedom and democracy at the core of our system of government. Under this view, society extends rights in exchange for an express or implied agreement from its members to submit to social responsibilities. In other words, rights are connected to moral agency and the ability to accept societal responsibility in exchange for those rights. ...

Needless to say, unlike human beings, chimpanzees cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities or be held legally accountable for their actions. In our view, it is this incapability to bear any legal responsibilities and societal duties that renders it inappropriate to confer upon chimpanzees the legal rights — such as the fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus — that have been afforded to human beings.

On December 18, 2014, the NhRP announced that it had filed a motion

for permission to appeal to New York's highest court, the Court of

Appeals.

Kiko's case

The NhRP also appealed the lower court's decision in Kiko's case.

Like Tommy's, Kiko's appeal was also granted and oral argument took

place on December 2, 2014 before the New York Supreme Court Appellate

Division, Fourth Department in Rochester, NY.

At Kiko's hearing the two main issues were: how could it be determined

that a chimpanzee actually wanted to be released, and could a transfer

to another location be considered as a release from confinement, the

purpose of the writ of habeas corpus.

NhRP argued that the issue of whether or not Kiko actually desired to

be released was regularly resolved in cases dealing with autonomous and

self-determining human beings who at that time are incompetent or are

too young to make those decisions. When asked which one of those grounds

is most similar to the circumstances of this petition, NhRP replied

that a chimpanzee is more akin to a child near the age of five rather

than a mentally disabled adult.

On January 2, 2015, the appellate court issued its decision,

denying the petition on the grounds that "habeas corpus does not lie

where a petitioner seeks only to change the conditions of confinement

rather than the confinement itself. We therefore conclude that habeas

corpus does not lie herein." Commenting on the Court's decision in a blog post on the NhRP's website, Wise wrote:

Yesterday the Fourth Department ignored both the Second Department and the Third Department. It threw out Kiko's case not because the NhRP had no right to appeal and, significantly, not because Kiko could not be a "person." It was, the court wrote, because not even a human being can use a writ of habeas corpus to move from a place of stark imprisonment to another place of vastly more freedom. (The NhRP is demanding that Kiko be moved from his solitary caged confinement to the spacious sanctuary of Save the Chimps in Fort Pierce, Florida, where he will live his life on a semi-tropical island surrounded by dozens of other chimpanzees.) Every single one of the eight cases cited by the Fourth Department concerns a human prisoner convicted of a crime using a writ of habeas corpus for some other purpose other than seeking immediate release from prison. The Fourth Department's decision treats Kiko as if he were a human prisoner convicted of a crime and ignores numerous cases spread over 200 years involving humans who were NOT prisoners convicted of a crime successfully using a writ of habeas corpus to move from one place to another. The NhRP will therefore be asking the Fourth Department for leave to file an appeal to the Court of Appeals within the next week. If the Fourth Department says "no," we will ask the Court of Appeals itself for leave to appeal.

On April 20, 2015, the NhRP filed a motion for permission to appeal in New York's highest court, the Court of Appeals.

Hercules and Leo Reconsidered

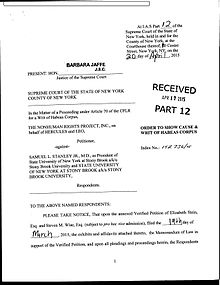

ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE & WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS

NhRP also filed an appeal to Hercules and Leo's lower court decision.

On April 3, 2014 the appeal was denied by the Second Appellate

Department in Brooklyn, this dismissal was based on a technicality and

NhRP's briefs were not considered.

On March 19, 2015, NhRP was allowed to refile the petition at the

county court in Manhattan which is under the First Appellate Department. Justice Barbra Jaffe was assigned to the case.

On April 20, 2015, Justice Barbra Jaffe issued an Order To Show Cause & Writ of Habeas Corpus.

A hearing was scheduled at which the State University of New York at

Stoney Brook was ordered to show why Hercules and Leo should be not be

released and transferred to the Save the Chimps sanctuary.

Because this order was titled as ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE & WRIT OF

HABEAS CORPUS it immediately made the headlines around the world as

granting the right to liberty to the chimpanzees.

"Justice Recognizes Two Chimpanzees as Legal Persons, Grants them Writ

of Habeas Corpus" was the headline of NhRP's breaking news post on its

website.

Because of the global headlines, Justice Jaffe's order was amended and

refiled with the phrase WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS manually crossed out.

It is likely that this was done to make it clear that the order was

granted only to allow a hearing for an evaluation of arguments made in

NhRP's petition.

The next day NhRP updated its posting stating that "the Order does not

necessarily mean that the Court has declared that the two chimpanzees,

Hercules and Leo, are legal persons for the purpose of an Article 70

common law writ of habeas corpus proceeding."

On May 27, a hearing was held for the purposes of the initial evaluation of Hercules and Leo's Petitions. Justice Jaffe's ruling was entered on July 29, 2015. In her ruling Justice Jaffe stated that in making her decision she was obliged to follow the ruling of a higher court.

Because of a conflict in relevant decisions of between the First

Department and the Fourth Department where Tommy's case was decided,

Justice Jaffe relied on the Third District's Tommy decision.

That appellate court ruled that a chimpanzee could not be considered a

person with the right to liberty because there is no precedent for such a

decision, and that rights cannot be granted without social

responsibilities. She further stated that even if she was not bound by

the Third Department decision in Tommy it should be up to the

legislature or higher courts given their role in setting government

policy.

Even though the petition was denied, NhRP interpreted Justice

Jaffe's decision as a victory. In his posting titled "That's One Small

Step for a Judge, One Giant Leap for the Nonhuman Rights Project", Mr.

Wise emphasized the fact that Justice Jaffe agreed with NhRP when

finding that "'persons' are not restricted to human beings, and that who

is a 'person' is not a question of biology, but of public policy and

principle." He finished by quoting the last paragraph of Justice Jaffe's decision:

Efforts to extend legal rights to chimpanzees are thus understandable; some day they may even succeed. Courts, however, are slow to embrace change, and occasionally seem reluctant to engage in bolder, more inclusive interpretations of the law, if only to the modest extent of affording them greater consideration. As Justice Kennedy aptly observed in Lawrence v. Texas (the 2003 gay rights case that struck down a state sodomy statute), albeit in a different context, "times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once though necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. The pace may be accelerating (citing the recent gay marriage case "granting the right to marry to same sex couples and acknowledging that institution of marriage has evolved over time notwithstanding its ancient origin"). For now, however, given the precedent to which I am bound, it is hereby ORDERED, that the petition for a writ of habeas corpus is denied.

Despite the ruling in its favor, the university

released an official statement that it would no longer conduct

scientific studies on Hercules and Leo.

An appeal was filed in August 2015, however that December Stony Brook

transferred the chimpanzees back the New Iberia Research Center, ending

the case, since the New York State Court no longer had jurisdiction over

them.

On September 1, 2015, NhRP's requests to file appeals to the highest court in Tommy's and Kiko's cases were denied.

On December 2, 2015 NhRP refiled Tommy's petition in the First

Department in Manhattan, New York City, this is the same district as the

one where Justice Jaffe issued her ruling.

The NhRP and PETA's slavery lawsuit

In October 2011, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filed a complaint in a California federal district court alleging that SeaWorld was enslaving its captive orcas in violation of the orcas' rights under the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The NhRP, while acknowledging that the orcas might be considered slaves

according to common usage of the term, vehemently opposed the lawsuit

on the grounds that it was strategically misguided and

counter-productive; the NhRP's critique highlighted the existence of

differing strategies for achieving rights and protections for nonhuman

animals.

"The claim that an orca is enslaved within the meaning of the

Thirteenth Amendment is unlikely even to receive a single vote from a

federal appellate court in 2011," Wise wrote on the NhRP's website. "It

is unthinkable that the present United States Supreme Court would

agree." In January 2012, the presiding judge, the Hon. Richard Miller, granted permission to the NhRP to appear in the case as an amicus curiae

(or Friend of the Court) to, as Wise said, "ensure that the orcas' best

interests are being properly represented, that their legal status is

advanced, and that an unfavorable ruling inflicts the least possible

harm on the development of an animal rights jurisprudence."

In February 2012, the case was dismissed. The judge wrote in his

ruling that "the only reasonable interpretation of the Thirteenth

Amendment's plain language is that it applies to persons, and not to

non-persons such as orcas." In an interview with the blog Earth in Transition, Wise said of the ruling

Sometimes it's better to do nothing than to do something harmful. The problem with the PETA suit is that it was doomed from the beginning, and we in the Nonhuman Rights Project immediately recognized that. When you study legal process you learn that the first cases in a new area often tend to take on an unusual level of importance. When you litigate in a novel area, you want to begin with your strongest suits in the most favorable jurisdictions. The rule for the Nonhuman Rights Project is: Win big and, if we must lose, lose small. PETA had virtually no chance of even winning small and a tremendous chance of losing big.

Documentary

Documentary filmmakers D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus announced in July 2012 that their next project, Unlocking the Cage, would follow the NhRP's efforts to achieve legal rights for nonhuman animals. In April 2014, Pennebaker-Hegedus Films released a preview of the as-yet-unfinished documentary in the form of a New York Times Op-Doc called Animals Are Persons Too. Unlocking the Cage was released in 2016.

Animal Charity Evaluators review

Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE) named NhRP one of its Standout Charities in its 2015 and 2016 annual charity recommendations.

ACE designates as Standout Charities those organizations which they do

not feel are as strong as their Top Charities, but which excel in at

least one way and are exceptionally strong compared to animal charities

in general.

Among the NhRP's strengths, according to ACE, is the fact that it

is the only organization they know of directly working towards legal

personhood for animals, which "could be the most promising avenue for

the proper consideration of nonhuman animals in our society." The NhRP

has also garnered public attention with their cases, which has plausibly

helped the animal advocacy cause. ACE states as a weakness NhRP's

focus on certain cognitively complex animals, and uncertainty about

whether the NhRP's activities will eventually expand to larger groups of

animals.