Cumulative current account balance 1980–2008 based on International Monetary Fund data.

Cumulative current account balance per capita 1980–2008 based on International Monetary Fund data.

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance of trade for goods versus one for services. The balance of trade measures a flow

of exports and imports over a given period of time. The notion of the

balance of trade does not mean that exports and imports are "in balance"

with each other.

If a country exports a greater value than it imports, it has a trade surplus or positive trade balance, and conversely, if a country imports a greater value than it exports, it has a trade deficit or negative trade balance. As of 2016, about 60 out of 200 countries have a trade surplus.

The notion that bilateral trade deficits are bad in and of themselves

is overwhelmingly rejected by trade experts and economists.

Explanation

Balance of trade in goods and services (Eurozone countries)

US trade balance from 1960

U.S. trade balance and trade policy (1895–2015)

U.K. balance of trade in goods (since 1870)

The balance of trade forms part of the current account, which includes other transactions such as income from the net international investment position

as well as international aid. If the current account is in surplus, the

country's net international asset position increases correspondingly.

Equally, a deficit decreases the net international asset position.

The trade balance is identical to the difference between a

country's output and its domestic demand (the difference between what

goods a country produces and how many goods it buys from abroad; this

does not include money re-spent on foreign stock, nor does it factor in

the concept of importing goods to produce for the domestic market).

Measuring the balance of trade can be problematic because of

problems with recording and collecting data. As an illustration of this

problem, when official data for all the world's countries are added up,

exports exceed imports by almost 1%; it appears the world is running a

positive balance of trade with itself. This cannot be true, because all

transactions involve an equal credit or debit

in the account of each nation. The discrepancy is widely believed to be

explained by transactions intended to launder money or evade taxes,

smuggling and other visibility problems. While the accuracy of

developing countries statistics would be suspicious, most of the

discrepancy actually occurs between developed countries of trusted

statistics.

Factors that can affect the balance of trade include:

- The cost of production (land, labor, capital, taxes, incentives, etc.) in the exporting economy vis-à-vis those in the importing economy;

- The cost and availability of raw materials, intermediate goods and other inputs;

- Currency exchange rate movements;

- Multilateral, bilateral and unilateral taxes or restrictions on trade;

- Non-tariff barriers such as environmental, health or safety standards;

- The availability of adequate foreign exchange with which to pay for imports; and

- Prices of goods manufactured at home (influenced by the responsiveness of supply)

In addition, the trade balance is likely to differ across the business cycle.

In export-led growth (such as oil and early industrial goods), the

balance of trade will shift towards exports during an economic

expansion.

However, with domestic demand-led growth (as in the United States and

Australia) the trade balance will shift towards imports at the same

stage in the business cycle.

The monetary balance of trade is different from the physical balance of trade

(which is expressed in amount of raw materials, known also as Total

Material Consumption). Developed countries usually import a substantial

amount of raw materials from developing countries. Typically, these

imported materials are transformed into finished products, and might be

exported after adding value. Financial trade balance statistics conceal

material flow. Most developed countries have a large physical trade

deficit, because they consume more raw materials than they produce. Many civil society organisations claim this imbalance is predatory and campaign for ecological debt repayment.

Examples

Historical example

Many countries in early modern Europe adopted a policy of mercantilism, which theorized that a trade surplus was beneficial to a country, among other elements such as colonialism and trade barriers with other countries and their colonies. (Bullionism was an early philosophy supporting mercantilism.)

Merchandise exports (1870–1992)

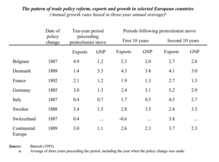

Trade policy, exports and growth in selected European countries

The practices and abuses of mercantilism led the natural resources and cash crops of British North America to be exported in exchange for finished goods from Great Britain, a factor leading to the American Revolution. An early statement appeared in Discourse of the Common Wealth of this Realm of England,

1549: "We must always take heed that we buy no more from strangers than

we sell them, for so should we impoverish ourselves and enrich them." Similarly a systematic and coherent explanation of balance of trade was made public through Thomas Mun's 1630 "England's treasure by foreign trade, or, The balance of our foreign trade is the rule of our treasure"

Since the mid-1980s, the United States has had a growing deficit in tradeable goods, especially with Asian nations (China and Japan) which now hold large sums of U.S debt that has in part funded the consumption.

The U.S. has a trade surplus with nations such as Australia. The issue

of trade deficits can be complex. Trade deficits generated in tradeable

goods such as manufactured goods or software may impact domestic

employment to different degrees than do trade deficits in raw materials.

Economies which have savings surpluses, such as Japan and

Germany, typically run trade surpluses. China, a high-growth economy,

has tended to run trade surpluses. A higher savings rate generally

corresponds to a trade surplus. Correspondingly, the U.S. with its lower

savings rate has tended to run high trade deficits, especially with

Asian nations.

Some have said that China pursues a mercantilist economic policy.

Russia pursues a policy based on protectionism, according to which

international trade is not a "win-win" game but a zero-sum game: surplus

countries get richer at the expense of deficit countries.

In 2016

|

Country example: Armenia

In

March 2019, Armenia recorded a trade deficit of US$203.90 Million. For

the last two decades, the Armenian trade balance has been negative,

reaching the all-time high of –33.98 USD Million in August, 2003. The

reason of trade deficit is because Armenia's foreign trade is limited

due to landlocked location and border disputes with Turkey and

Azerbaijan, from the west and east sides respectively. The situation

results in the country's usual report of high trade deficits.

Views on economic impact

The

notion that bilateral trade deficits are bad in and of themselves is

overwhelmingly rejected by trade experts and economists. According to the IMF trade deficits can cause a balance of payments problem, which can affect foreign exchange shortages and hurt countries. On the other hand, Joseph Stiglitz

points out that countries running surpluses exert a "negative

externality" on trading partners and pose a threat to global

prosperity, far more than those in deficit. Ben Bernanke

argues that "persistent imbalances within the euro zone are...

unhealthy, as they lead to financial imbalances as well as to unbalanced

growth. The fact that Germany is selling so much more than it is buying

redirects demand from its neighbors (as well as from other countries

around the world), reducing output and employment outside Germany."

A 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research paper by economists

at the International Monetary Fund and University of California,

Berkeley, found in a study of 151 countries over 1963-2014 that the

imposition of tariffs had little effect on the trade balance.

Classical theory

Adam Smith on the balance of trade

In the foregoing part of this chapter I have endeavoured to show, even upon the principles of the commercial system, how unnecessary it is to lay extraordinary restraints upon the importation of goods from those countries with which the balance of trade is supposed to be disadvantageous. Nothing, however, can be more absurd than this whole doctrine of the balance of trade, upon which, not only these restraints, but almost all the other regulations of commerce are founded. When two places trade with one another, this [absurd] doctrine supposes that, if the balance be even, neither of them either loses or gains; but if it leans in any degree to one side, that one of them loses and the other gains in proportion to its declension from the exact equilibrium.

— Smith, 1776, book IV, ch. iii, part ii

Keynesian theory

In the last few years of his life, John Maynard Keynes was much preoccupied with the question of balance in international trade. He was the leader of the British delegation to the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in 1944 that established the Bretton Woods system of international currency management.

He was the principal author of a proposal – the so-called Keynes Plan – for an International Clearing Union.

The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of

settling outstanding balances should be solved by 'creating' additional

'international money', and that debtor and creditor should be treated

almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium. In the event, though, the

plans were rejected, in part because "American opinion was naturally

reluctant to accept the principle of equality of treatment so novel in

debtor-creditor relationships".

The new system is not founded on free-trade (liberalisation of foreign trade)

but rather on the regulation of international trade, in order to

eliminate trade imbalances: the nations with a surplus would have a

powerful incentive to get rid of it, and in doing so they would

automatically clear other nations deficits.

He proposed a global bank that would issue its own currency – the

bancor – which was exchangeable with national currencies at fixed rates

of exchange and would become the unit of account between nations, which

means it would be used to measure a country's trade deficit or trade

surplus. Every country would have an overdraft facility in its bancor

account at the International Clearing Union. He pointed out that

surpluses lead to weak global aggregate demand – countries running

surpluses exert a "negative externality" on trading partners, and posed

far more than those in deficit, a threat to global prosperity.

In "National Self-Sufficiency" The Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4 (June 1933), he already highlighted the problems created by free trade.

His view, supported by many economists and commentators at the

time, was that creditor nations may be just as responsible as debtor

nations for disequilibrium in exchanges and that both should be under an

obligation to bring trade back into a state of balance. Failure for

them to do so could have serious consequences. In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, then editor of The Economist,

"If the economic relationships between nations are not, by one means or

another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of

financial arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing

results of chaos."

These ideas were informed by events prior to the Great Depression

when – in the opinion of Keynes and others – international lending,

primarily by the U.S., exceeded the capacity of sound investment and so

got diverted into non-productive and speculative uses, which in turn

invited default and a sudden stop to the process of lending.

Influenced by Keynes, economics texts in the immediate post-war

period put a significant emphasis on balance in trade. For example, the

second edition of the popular introductory textbook, An Outline of Money,

devoted the last three of its ten chapters to questions of foreign

exchange management and in particular the 'problem of balance'. However,

in more recent years, since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the increasing influence of monetarist

schools of thought in the 1980s, and particularly in the face of large

sustained trade imbalances, these concerns – and particularly concerns

about the destabilising effects of large trade surpluses – have largely

disappeared from mainstream economics discourse and Keynes' insights have slipped from view. They are receiving some attention again in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–08.

Monetarist theory

Prior to 20th century monetarist theory, the 19th century economist and philosopher Frédéric Bastiat

expressed the idea that trade deficits actually were a manifestation of

profit, rather than a loss. He proposed as an example to suppose that

he, a Frenchman, exported French wine and imported British coal, turning

a profit. He supposed he was in France, and sent a cask of wine which

was worth 50 francs to England. The customhouse would record an export

of 50 francs. If, in England, the wine sold for 70 francs (or the pound

equivalent), which he then used to buy coal, which he imported into

France, and was found to be worth 90 francs in France, he would have

made a profit of 40 francs. But the customhouse would say that the value

of imports exceeded that of exports and was trade deficit against the

ledger of France.

By reductio ad absurdum,

Bastiat argued that the national trade deficit was an indicator of a

successful economy, rather than a failing one. Bastiat predicted that a

successful, growing economy would result in greater trade deficits, and

an unsuccessful, shrinking economy would result in lower trade deficits.

This was later, in the 20th century, echoed by economist Milton Friedman.

In the 1980s, Milton Friedman, a Nobel Memorial Prize-winning economist and a proponent of monetarism,

contended that some of the concerns of trade deficits are unfair

criticisms in an attempt to push macroeconomic policies favorable to

exporting industries.

Friedman argued that trade deficits are not necessarily

important, as high exports raise the value of the currency, reducing

aforementioned exports, and vice versa for imports, thus naturally

removing trade deficits not due to investment. Since 1971, when

the Nixon administration decided to abolish fixed exchange rates,

America's Current Account accumulated trade deficits have totaled $7.75

trillion as of 2010. This deficit exists as it is matched by investment

coming into the United States – purely by the definition of the balance

of payments, any current account deficit that exists is matched by an

inflow of foreign investment.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the U.S. had experienced high

inflation and Friedman's policy positions tended to defend the stronger

dollar at that time. He stated his belief that these trade deficits were

not necessarily harmful to the economy at the time since the currency

comes back to the country (country A sells to country B, country B sells

to country C who buys from country A, but the trade deficit only

includes A and B). However, it may be in one form or another including

the possible tradeoff of foreign control of assets. In his view, the

"worst-case scenario" of the currency never returning to the country of

origin was actually the best possible outcome: the country actually

purchased its goods by exchanging them for pieces of cheaply made paper.

As Friedman put it, this would be the same result as if the exporting

country burned the dollars it earned, never returning it to market

circulation.

This position is a more refined version of the theorem first discovered by David Hume.

Hume argued that England could not permanently gain from exports,

because hoarding gold (i.e., currency) would make gold more plentiful in

England; therefore, the prices of English goods would rise, making them

less attractive exports and making foreign goods more attractive

imports. In this way, countries' trade balances would balance out.

Friedman presented his analysis of the balance of trade in Free to Choose, widely considered his most significant popular work.

Trade balance’s effects upon a nation's GDP

Exports

directly increase and imports directly reduce a nation's balance of

trade (i.e. net exports). A trade surplus is a positive net balance of

trade, and a trade deficit is a negative net balance of trade. Due to

the balance of trade being explicitly added to the calculation of the

nation's gross domestic product using the expenditure method of

calculating gross domestic product (i.e. GDP), trade surpluses are

contributions and trade deficits are "drags" upon their nation's GDP.

Balance of trade vs. balance of payments

| Balance of trade | Balance of payments |

|---|---|

| Includes only visible imports and exports, i.e. imports and exports of merchandise. The difference between exports and imports is called the balance of trade. If imports are greater than exports, it is sometimes called an unfavourable balance of trade. If exports exceed imports, it is sometimes called a favourable balance of trade. | Includes all those visible and invisible items exported from and imported into the country in addition to exports and imports of merchandise. |

| Includes revenues received or paid on account of imports and exports of merchandise. It shows only revenue items. | Includes all revenue and capital items whether visible or non-visible. The balance of trade thus forms a part of the balance of payments. |