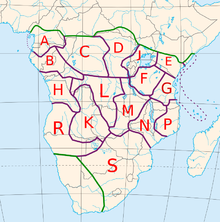

Bantu-speaking areas of Africa, divided into zones following the Guthrie classification.

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| African Great Lakes, Central Africa, Southern Africa | |

| Languages | |

| Bantu languages (over 535) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity, traditional faiths; minority Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Southern Bantoid people |

Bantu are the speakers of Ntu languages, comprising several hundred indigenous ethnic groups in sub-Saharan Africa, spread over a vast area from Central Africa across the African Great Lakes to Southern Africa. Linguistically, these languages belong to the Southern Bantoid branch of Benue–Congo, one of the language families grouped within the Niger–Congo phylum.

The total number of languages ranges in the hundreds, depending on the definition of "language" or "dialect", estimated at between 440 and 680 distinct languages. The total number of speakers is in the hundreds of millions, ranging at roughly 350 million in the mid-2010s (roughly 30% of the population of Africa, or roughly 5% of the total world population). About 60 million speakers (2015), divided into some 200 ethnic or tribal groups, are found in the Democratic Republic of Congo alone.

The larger of the individual Bantu groups have populations of several million, e.g. the Shona of Zimbabwe (12 million as of 2000), the Zulu of South Africa (12 million as of 2005) the Luba of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (7 million as of 2010), the Sukuma of Tanzania (9 million as of 2016), or the Kikuyu of Kenya (7 million as of 2010).

Origin of the Name Bantu

Map

of the major Bantu languages (shown in purple), with the non-Bantu

Southern Bantoid languages indicated in grey (northwestern corner)

The word Bantu for the language families and its speakers is an artificial term based on the reconstructed Proto-Ntu term for "people" or "humans". It was first introduced (as Bâ-ntu) by Wilhelm Bleek in 1857 or 1858, and popularised in his Comparative Grammar of 1862.

The name was coined to represent the word for "people" in loosely reconstructed Proto-Ntu, from the plural

noun class prefix *ba- categorizing "people", and the root *ntʊ̀ - "some (entity), any" (e.g. Zulu umuntu "person", abantu "people", into "thing", izinto

"things").

There is no native term for the group, as populations refer to their

languages by ethnic endonyms but did not have a concept for the larger

ethno-linguistic phylum. Bleek's coinage was inspired by the

anthropological observation of groups self-identifying as "people" or

"the true people". That is, idiomatically the reflexes of *bantʊ in the numerous languages often have connotations of personal character traits as encompassed under the values system of ubuntu, also known as hunhu in Chishona or botho in Sesotho, rather than just referring to all human beings.

The root in Proto-Ntu is reconstructed as *-ntʊ́. Versions of the word Bantu (that is, the root plus the class 2 noun class prefix *ba-) occur in all Bantu languages: for example, as watu in Swahili; bantu in Kikongo; anthu in Chichewa; batu in Lingala; bato in Kiluba; bato in Duala; abanto in Gusii; andũ in Kamba and Kikuyu; abantu in Kirundi, Zulu, Xhosa, Runyakitara, and Ganda; wandru in Shingazidja; abantru in Mpondo and Ndebele; bãthfu in Phuthi; bantfu in Swati; banu in Lala; vanhu in Shona and Tsonga; batho in Sesotho, Tswana and Northern Sotho; antu in Meru; andu in Embu; vandu in some Luhya dialects; vhathu in Venda; and bhandu in Nyakyusa.

History

Origins and expansion

1 = 2000–1500 BC origin

2 = ca. 1500 BC first dispersal

2.a = Eastern Bantu, 2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000–500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4–7 = southward advance

9 = 500 BC–0 Congo nucleus

10 = 0–1000 AD last phase

2 = ca. 1500 BC first dispersal

2.a = Eastern Bantu, 2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000–500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4–7 = southward advance

9 = 500 BC–0 Congo nucleus

10 = 0–1000 AD last phase

Ntu languages are theorised to derive from the Proto-Ntu reconstructed language, estimated to have been spoken about 4,000 to 3,000 years ago in West/Central Africa (the area of modern-day Cameroon).

They were supposedly spread across Central, Eastern and Southern Africa in the so-called Bantu expansion, a rapid dissemination during the 1st millennium BC, in one wave moving across the Congo basin towards East Africa, in another moving south along the African coast and the Congo River system towards Angola. This concept has often been framed as a mass-migration, but Jan Vansina

and others have argued that it was actually a cultural spread and not

the movement of any specific populations that could be defined as an

enormous group simply on the basis of common language traits.

The geographical origin of the (Ba)Ntu expansion is somewhat open to debate.

Two main scenarios are proposed, an early expansion to Central Africa, and

a single origin of the dispersal radiating from there,

or an early separation into an eastward and a southward wave of dispersal. In terms of migration, genetic analysis shows a significant clustering

of genetic traits by region, suggesting admixture from local

populations.

According to the early-split scenario described in the 1990s,

the southward dispersal had reached the Central African rain forest by

about 1500 BC, and the southern Savannahs by 500 BC, while the eastward

dispersal

reached the Great Lakes

by 1000 BC,

expanding further from there, as the rich environment supported a dense

population. Possible movements by small groups to the southeast from the

Great Lakes region could have been more rapid, with initial settlements

widely dispersed near the coast and near rivers, due to comparatively

harsh farming conditions in areas farther from water. Under the

migration hypothesis, pioneering groups would have had reached modern KwaZulu-Natal

in South Africa by about AD 300 along the coast, and the modern

Northern Province (encompassed within the former province of the Transvaal) by AD 500.

Under this migration hypothesis, the Bantu peoples would have

assimilated and/or displaced a number of earlier inhabitants that they

came across, such as Pygmy and Khoisan populations in the centre and south, respectively. They would have also encountered some Afro-Asiatic outlier groups in the southeast (mainly Cushitic),

as well as Nilo-Saharan (mainly Nilotic and Sudanic) groups.

As cattle terminology in use amongst the few modern Bantu pastoralist groups suggests, it is plausible that the acquisition of cattle

was from their Cushitic-speaking neighbors. Linguistic evidence also

indicates that the custom of milking cattle was also directly from

Cushitic cultures in the area.

Later interactions between Ntu-speaking and Cushitic-speaking peoples

resulted in groups with significant complexity, such as the Tutsi of the African Great Lakes region; and culturo-linguistic influences, such as the Herero herdsmen of southern Africa.

Later history

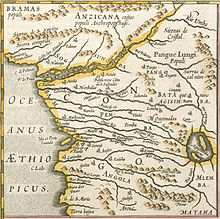

The Bantu Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1630

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Bantu-speaking states began to

emerge in the Great Lakes region and in the savannah south of the

Central African rain forest. On the Zambezi river, the Monomatapa kings built the Great Zimbabwe complex, a civilisation ancestral to the Shona people.

Comparable sites in Southern Africa, include Bumbusi in Zimbabwe and Manyikeni in Mozambique.

From the 12th century onward, the processes of state formation

amongst Bantu peoples increased in frequency. This was probably due to

denser population (which led to more specialized divisions of labor,

including military power, while making emigration more difficult); to

technological developments in economic activity; and to new techniques

in the political-spiritual ritualization of royalty as the source of

national strength and health.

Some examples of such Bantu states include: in Central Africa, the Kingdom of Kongo, Lunda Empire, Luba Empire of Angola, the Buganda Kingdoms of Uganda and Tanzania; and in Southern Africa, the Mutapa Empire, the Danamombe, Khami, and Naletale Kingdoms of Zimbabwe and Mozambique and the Rozwi Empire.

On the coastal section of East Africa, a mixed Bantu community developed through contact with Muslim Arab and Persian traders, Zanzibar being an important port in the Arab slave trade.

The Swahili culture

that emerged from these exchanges evinces many Arab and Islamic

influences not seen in traditional Bantu culture, as do the many Afro-Arab members of the Bantu Swahili people.

With its original speech community centered on the coastal parts of

Zanzibar, Kenya, and Tanzania – a seaboard referred to as the Swahili Coast – the Bantu Swahili language contains many Arabic loan-words as a result of these interactions.

The Arab slave trade also brought Bantu influence to Madagascar,

the Malagasy people showing Bantu admixture, and their Malagasy language Bantu loans.

Toward the 18th and 19th centuries, the flow of Zanj (Bantu) slaves from Southeast Africa increased with the rise of the Omani Sultanate of Zanzibar,

based in Zanzibar, Tanzania. With the arrival of European colonialists,

the Zanzibar Sultanate came into direct trade conflict and competition

with Portuguese

and other Europeans along the Swahili Coast, leading eventually to the

fall of the Sultanate and the end of slave trading on the Swahili Coast

in the mid-20th century.

Use of the term "Bantu" in South Africa

A Zulu traditional dancer in Southern Africa

In the 1920s, relatively liberal South Africans, missionaries, and

the small black intelligentsia began to use the term "Bantu" in

preference to "Native". After World War II, the National Party

governments adopted that usage officially, while the growing African

nationalist movement and its liberal allies turned to the term "African"

instead, so that "Bantu" became identified with the policies of apartheid.

By the 1970s this so discredited "Bantu" as an ethno-racial designation

that the apartheid government switched to the term "Black" in its

official racial categorizations, restricting it to Bantu-speaking

Africans, at about the same time that the Black Consciousness Movement led by Steve Biko and others were defining "Black" to mean all non-European South Africans (Bantus, Khoisan, Coloureds, and Indians).

Examples of South African usages of "Bantu" include:

- One of South Africa's politicians of recent times, General Bantubonke Harrington Holomisa (Bantubonke is a compound noun meaning "all the people"), is known as Bantu Holomisa.

- The South African apartheid governments originally gave the name "bantustans" to the eleven rural reserve areas intended for nominal independence to deny indigenous Bantu South Africans citizenship. "Bantustan" originally reflected an analogy to the various ethnic "-stans" of Western and Central Asia. Again association with apartheid discredited the term, and the South African government shifted to the politically appealing but historically deceptive term "ethnic homelands". Meanwhile, the anti-apartheid movement persisted in calling the areas bantustans, to drive home their political illegitimacy.

- The abstract noun ubuntu, humanity or humaneness, is derived regularly from the Nguni noun stem -ntu in Xhosa, Zulu, and Ndebele. In Swati the stem is -ntfu and the noun is buntfu.

- In the Sotho–Tswana languages of southern Africa, batho is the cognate term to Nguni abantu, illustrating that such cognates need not actually look like the -ntu root exactly. The early African National Congress of South Africa had a newspaper called Abantu-Batho from 1912–1933, which carried columns in English, Zulu, Sotho, and Xhosa.