Solar System

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Sun and planets of the Solar System. Sizes but not distances are to scale.

| |

| Age | 4.568 billion years |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| System mass | 1.0014 Solar masses |

| Nearest star |

|

| Nearest known planetary system | Alpha Centauri system (4.37 ly) |

| Planetary system | |

| Semi-major axis of outer planet (Neptune) | 30.10 AU (4.503 billion km) |

| Distance to Kuiper cliff | 50 AU |

Populations

| |

| Stars | 1 (Sun) |

| Planets | |

| Known dwarf planets | |

| Known natural satellites |

427

|

| Known minor planets | 644,275 (as of 2014-06-18)[4] |

| Known comets | 3,272 (as of 2014-06-18)[4] |

| Identified rounded satellites | 19 |

| Orbit about Galactic Center | |

| Invariable-to-galactic plane inclination | 60.19°8 (ecliptic) |

| Distance to Galactic Center | 27,000 ± 1,000 ly |

| Orbital speed | 220 km/s |

| Orbital period | 225–250 Myr |

| Star-related properties | |

| Spectral type | G2V |

| Frost line | ≈5 AU[5] |

| Distance to heliopause | ≈120 AU |

| Hill sphere radius | ≈1–2 ly |

The Solar System[a] comprises the Sun and the objects that orbit it, whether they orbit it directly or by orbiting other objects that orbit it directly.[b] Of those objects that orbit the Sun directly, the largest eight are the planets[c] that form the planetary system around it, while the remainder are significantly smaller objects, such as dwarf planets and small Solar System bodies (SSSBs) such as comets and asteroids.[d]

The Solar System formed 4.6 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud. The vast majority of the system's mass is in the Sun, with most of the remaining mass contained in Jupiter. The four smaller inner planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, also called the terrestrial planets, are primarily composed of rock and metal. The four outer planets, called the gas giants, are substantially more massive than the terrestrials. The two largest, Jupiter and Saturn, are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium; the two outermost planets, Uranus and Neptune, are composed largely of substances with relatively high melting points (compared with hydrogen and helium), called ices, such as water, ammonia and methane, and are often referred to separately as "ice giants". All planets have almost circular orbits that lie within a nearly flat disc called the ecliptic plane.

The Solar System also contains regions populated by smaller objects.[d] The asteroid belt, which lies between Mars and Jupiter, mostly contains objects composed, like the terrestrial planets, of rock and metal. Beyond Neptune's orbit lie the Kuiper belt and scattered disc, linked populations of trans-Neptunian objects composed mostly of ices. Within these populations are several dozen to more than ten thousand objects that may be large enough to have been rounded by their own gravity.[10] Such objects are referred to as dwarf planets. Identified dwarf planets include the asteroid Ceres and the trans-Neptunian objects Pluto and Eris.[d] In addition to these two regions, various other small-body populations, including comets, centaurs and interplanetary dust, freely travel between regions. Six of the planets, at least three of the dwarf planets, and many of the smaller bodies are orbited by natural satellites,[e] usually termed "moons" after Earth's Moon. Each of the outer planets is encircled by planetary rings of dust and other small objects.

The solar wind, a flow of plasma from the Sun, creates a bubble in the interstellar medium known as the heliosphere, which extends out to the edge of the scattered disc. The Oort cloud, which is believed to be the source for long-period comets, may also exist at a distance roughly a thousand times further than the heliosphere. The heliopause is the point at which pressure from the solar wind is equal to the opposing pressure of interstellar wind. The Solar System is located in the Orion Arm, 26,000 light years from the center of the Milky Way.

Discovery and exploration

Andreas Cellarius's illustration of the Copernican system, from the Harmonia Macrocosmica (1660)

For many thousands of years, humanity, with a few notable exceptions, did not recognize the existence of the Solar System. People believed Earth to be stationary at the centre of the universe and categorically different from the divine or ethereal objects that moved through the sky. Although the Greek philosopher Aristarchus of Samos had speculated on a heliocentric reordering of the cosmos,[11] Nicolaus Copernicus was the first to develop a mathematically predictive heliocentric system.[12] His 17th-century successors, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, developed an understanding of physics that led to the gradual acceptance of the idea that Earth moves around the Sun and that the planets are governed by the same physical laws that governed Earth. Additionally, the invention of the telescope led to the discovery of further planets and moons. In more recent times, improvements in the telescope and the use of unmanned spacecraft have enabled the investigation of geological phenomena, such as mountains and craters, and seasonal meteorological phenomena, such as clouds, dust storms, and ice caps on the other planets.

Structure and composition

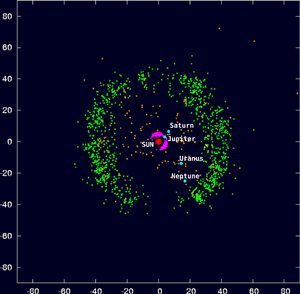

The orbits of the bodies in the Solar System to scale (clockwise from top left)

The principal component of the Solar System is the Sun, a G2 main-sequence star that contains 99.86% of the system's known mass and dominates it gravitationally.[13] The Sun's four largest orbiting bodies, the gas giants, account for 99% of the remaining mass, with Jupiter and Saturn together comprising more than 90%.[f]

Most large objects in orbit around the Sun lie near the plane of Earth's orbit, known as the ecliptic. The planets are very close to the ecliptic, whereas comets and Kuiper belt objects are frequently at significantly greater angles to it.[17][18] All the planets and most other objects orbit the Sun in the same direction that the Sun is rotating (counter-clockwise, as viewed from a long way above Earth's north pole).[19] There are exceptions, such as Halley's Comet.

The overall structure of the charted regions of the Solar System consists of the Sun, four relatively small inner planets surrounded by a belt of rocky asteroids, and four gas giants surrounded by the Kuiper belt of icy objects. Astronomers sometimes informally divide this structure into separate regions. The inner Solar System includes the four terrestrial planets and the asteroid belt. The outer Solar System is beyond the asteroids, including the four gas giants.[20] Since the discovery of the Kuiper belt, the outermost parts of the Solar System are considered a distinct region consisting of the objects beyond Neptune.[21]

Most of the planets in the Solar System possess secondary systems of their own, being orbited by planetary objects called natural satellites, or moons (two of which are larger than the planet Mercury), and, in the case of the four gas giants, by planetary rings, thin bands of tiny particles that orbit them in unison. Most of the largest natural satellites are in synchronous rotation, with one face permanently turned toward their parent.

Kepler's laws of planetary motion describe the orbits of objects about the Sun. Following Kepler's laws, each object travels along an ellipse with the Sun at one focus. Objects closer to the Sun (with smaller semi-major axes) travel more quickly because they are more affected by the Sun's gravity. On an elliptical orbit, a body's distance from the Sun varies over the course of its year. A body's closest approach to the Sun is called its perihelion, whereas its most distant point from the Sun is called its aphelion. The orbits of the planets are nearly circular, but many comets, asteroids, and Kuiper belt objects follow highly elliptical orbits. The positions of the bodies in the Solar System can be predicted using numerical models.

Although the Sun dominates the system by mass, it accounts for only about 2% of the angular momentum[22] due to the differential rotation within the gaseous Sun.[23] The planets, dominated by Jupiter, account for most of the rest of the angular momentum due to the combination of their mass, orbit, and distance from the Sun, with a possibly significant contribution from comets.[22]

The Sun, which comprises nearly all the matter in the Solar System, is composed of roughly 98% hydrogen and helium.[24] Jupiter and Saturn, which comprise nearly all the remaining matter, possess atmospheres composed of roughly 99% of these elements.[25][26] A composition gradient exists in the Solar System, created by heat and light pressure from the Sun; those objects closer to the Sun, which are more affected by heat and light pressure, are composed of elements with high melting points.

Objects farther from the Sun are composed largely of materials with lower melting points.[27] The boundary in the Solar System beyond which those volatile substances could condense is known as the frost line, and it lies at roughly 5 AU from the Sun.[5]

The objects of the inner Solar System are composed mostly of rock,[28] the collective name for compounds with high melting points, such as silicates, iron or nickel, that remained solid under almost all conditions in the protoplanetary nebula.[29] Jupiter and Saturn are composed mainly of gases, the astronomical term for materials with extremely low melting points and high vapour pressure, such as molecular hydrogen, helium, and neon, which were always in the gaseous phase in the nebula.[29] Ices, like water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide,[28] have melting points up to a few hundred kelvins.[29] They can be found as ices, liquids, or gases in various places in the Solar System, whereas in the nebula they were either in the solid or gaseous phase.[29]

Icy substances comprise the majority of the satellites of the giant planets, as well as most of Uranus and Neptune (the so-called "ice giants") and the numerous small objects that lie beyond Neptune's orbit.[28][30] Together, gases and ices are referred to as volatiles.[31]

Distances and scales

The distance from Earth to the Sun is 1 astronomical unit (150,000,000 km). For comparison, the radius of the Sun is 0.0047 AU (700,000 km). Thus, the Sun occupies 0.00001% (10−5 %) of the volume of a sphere with a radius the size of Earth's orbit, whereas Earth's volume is roughly one millionth (10−6) that of the Sun. Jupiter, the largest planet, is 5.2 astronomical units (780,000,000 km) from the Sun and has a radius of 71,000 km (0.00047 AU), whereas the most distant planet, Neptune, is 30 AU (4.5×109 km) from the Sun.

With a few exceptions, the farther a planet or belt is from the Sun, the larger the distance between its orbit and the orbit of the next nearer object to the Sun. For example, Venus is approximately 0.33 AU farther out from the Sun than Mercury, whereas Saturn is 4.3 AU out from Jupiter, and Neptune lies 10.5 AU out from Uranus. Attempts have been made to determine a relationship between these orbital distances (for example, the Titius–Bode law),[32] but no such theory has been accepted. The images at the beginning of this section show the orbits of the various constituents of the Solar System on different scales.

Some Solar System models attempt to convey the relative scales involved in the Solar System on human terms. Some are small in scale (and may be mechanical—called orreries)—whereas others extend across cities or regional areas.[33] The largest such scale model, the Sweden Solar System, uses the 110-metre (361-ft) Ericsson Globe in Stockholm as its substitute Sun, and, following the scale, Jupiter is a 7.5-metre (25-foot) sphere at Arlanda International Airport, 40 km (25 mi) away, whereas the farthest current object, Sedna, is a 10-cm (4-in) sphere in Luleå, 912 km (567 mi) away.[34][35]

If the Sun–Neptune distance is scaled to 100 metres, then the Sun is about 3 cm in diameter (roughly two-thirds the diameter of a golf ball), the gas giants all smaller than about 3 mm. Earth's diameter along with the other terrestrial planets would be smaller than a flea (0.3 mm) at this scale.[36]

Distances of selected bodies of the Solar System from the Sun. The left and right edges of each bar correspond to the perihelion and aphelion of the body, respectively. Long bars denote high orbital eccentricity. The radius of the Sun is 0.7 million km, and the radius of Jupiter (the largest planet) is 0.07 million km, both too small to resolve on this image.

Formation and evolution

The Solar System formed 4.568 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a region within a large molecular cloud.[37] This initial cloud was likely several light-years across and probably birthed several stars.[38] As is typical of molecular clouds, this one consisted mostly of hydrogen, with some helium, and small amounts of heavier elements fused by previous generations of stars. As the region that would become the Solar System, known as the pre-solar nebula,[39] collapsed, conservation of angular momentum caused it to rotate faster. The centre, where most of the mass collected, became increasingly hotter than the surrounding disc.[38] As the contracting nebula rotated faster, it began to flatten into a protoplanetary disc with a diameter of roughly 200 AU[38] and a hot, dense protostar at the centre.[40][41] The planets formed by accretion from this disc,[42] in which dust and gas gravitationally attracted each other, coalescing to form ever larger bodies. Hundreds of protoplanets may have existed in the early Solar System, but they either merged or were destroyed, leaving the planets, dwarf planets, and leftover minor bodies.

Due to their higher boiling points, only metals and silicates could exist in solid form in the warm inner Solar System close to the Sun, and these would eventually form the rocky planets of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Because metallic elements only comprised a very small fraction of the solar nebula, the terrestrial planets could not grow very large. The giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) formed further out, beyond the frost line, the point between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where material is cool enough for volatile icy compounds to remain solid. The ices that formed these planets were more plentiful than the metals and silicates that formed the terrestrial inner planets, allowing them to grow massive enough to capture large atmospheres of hydrogen and helium, the lightest and most abundant elements. Leftover debris that never became planets congregated in regions such as the asteroid belt, Kuiper belt, and Oort cloud. The Nice model is an explanation for the creation of these regions and how the outer planets could have formed in different positions and migrated to their current orbits through various gravitational interactions.

Within 50 million years, the pressure and density of hydrogen in the centre of the protostar became great enough for it to begin thermonuclear fusion.[43] The temperature, reaction rate, pressure, and density increased until hydrostatic equilibrium was achieved: the thermal pressure equalled the force of gravity. At this point, the Sun became a main-sequence star.[44] Solar wind from the Sun created the heliosphere and swept away the remaining gas and dust from the protoplanetary disc into interstellar space, ending the planetary formation process.

The Solar System will remain roughly as we know it today until the hydrogen in the core of the Sun has been entirely converted to helium, which will occur roughly 5.4 billion years from now. This will mark the end of the Sun's main-sequence life. At this time, the core of the Sun will collapse, and the energy output will be much greater than at present. The outer layers of the Sun will expand to roughly 260 times its current diameter, and the Sun will become a red giant. Because of its vastly increased surface area, the surface of the Sun will be considerably cooler (2,600 K at its coolest) than it is on the main sequence.[45] The expanding Sun is expected to vaporize Mercury and Venus and render Earth uninhabitable as the habitable zone moves out to the orbit of Mars. Eventually, the core will be hot enough for helium fusion; the Sun will burn helium for a fraction of the time it burned hydrogen in the core. The Sun is not massive enough to commence the fusion of heavier elements, and nuclear reactions in the core will dwindle. Its outer layers will move away into space, leaving a white dwarf, an extraordinarily dense object, half the original mass of the Sun but only the size of Earth.[46] The ejected outer layers will form what is known as a planetary nebula, returning some of the material that formed the Sun—but now enriched with heavier elements like carbon—to the interstellar medium.

Sun

The Sun is the Solar System's star, and by far its chief component. Its large mass (332,900 Earth masses)[47] produces temperatures and densities in its core high enough to sustain nuclear fusion,[48] which releases enormous amounts of energy, mostly radiated into space as electromagnetic radiation, peaking in the 400–700 nm band of visible light.[49]

The Sun is a type G2 main-sequence star. Compared to the majority of stars in the Milky Way, the Sun is rather large and bright.[50] Stars are classified by the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, a graph that plots the brightness of stars with their surface temperatures. Generally, hotter stars are brighter. Stars following this pattern are said to be on the main sequence, and the Sun lies right in the middle of it. Stars brighter and hotter than the Sun are rare, whereas substantially dimmer and cooler stars, known as red dwarfs, are common, making up 85% of the stars in the galaxy.[50][51]

Evidence suggests that the Sun's position on the main sequence puts it in the "prime of life" for a star, not yet having exhausted its store of hydrogen for nuclear fusion. The Sun is growing brighter; early in its history its brightness was 70% that of what it is today.[52]

The Sun is a population I star; it was born in the later stages of the universe's evolution and thus contains more elements heavier than hydrogen and helium ("metals" in astronomical parlance) than the older population II stars.[53] Elements heavier than hydrogen and helium were formed in the cores of ancient and exploding stars, so the first generation of stars had to die before the universe could be enriched with these atoms. The oldest stars contain few metals, whereas stars born later have more. This high metallicity is thought to have been crucial to the Sun's development of a planetary system because the planets form from the accretion of "metals".[54]

Interplanetary medium

The vast majority of the Solar System consists of a near-vacuum known as the interplanetary medium. Along with light, the Sun radiates a continuous stream of charged particles (a plasma) known as the solar wind. This stream of particles spreads outwards at roughly 1.5 million kilometres (932 thousand miles) per hour,[55] creating a tenuous atmosphere (the heliosphere) that permeates the interplanetary medium out to at least 100 AU (see heliopause).[56] Activity on the Sun's surface, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections, disturb the heliosphere, creating space weather and causing geomagnetic storms.[57] The largest structure within the heliosphere is the heliospheric current sheet, a spiral form created by the actions of the Sun's rotating magnetic field on the interplanetary medium.[58][59]

Earth's magnetic field stops its atmosphere from being stripped away by the solar wind.[60] Venus and Mars do not have magnetic fields, and as a result the solar wind is causing their atmospheres to gradually bleed away into space.[61] Coronal mass ejections and similar events blow a magnetic field and huge quantities of material from the surface of the Sun. The interaction of this magnetic field and material with Earth's magnetic field funnels charged particles into Earth's upper atmosphere, where its interactions create aurorae seen near the magnetic poles.

The heliosphere and planetary magnetic fields (for those planets that have them) partially shield the Solar System from high-energy interstellar particles called cosmic rays. The density of cosmic rays in the interstellar medium and the strength of the Sun's magnetic field change on very long timescales, so the level of cosmic-ray penetration in the Solar System varies, though by how much is unknown.[62]

The interplanetary medium is home to at least two disc-like regions of cosmic dust. The first, the zodiacal dust cloud, lies in the inner Solar System and causes the zodiacal light. It was likely formed by collisions within the asteroid belt brought on by interactions with the planets.[63] The second dust cloud extends from about 10 AU to about 40 AU, and was probably created by similar collisions within the Kuiper belt.[64][65]

Inner Solar System

The inner Solar System is the traditional name for the region comprising the terrestrial planets and asteroids.[66] Composed mainly of silicates and metals, the objects of the inner Solar System are relatively close to the Sun; the radius of this entire region is shorter than the distance between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn.Inner planets

Main article: Terrestrial planet

The four inner or terrestrial planets have dense, rocky compositions, few or no moons, and no ring systems. They are composed largely of refractory minerals, such as the silicates, which form their crusts and mantles, and metals, such as iron and nickel, which form their cores. Three of the four inner planets (Venus, Earth and Mars) have atmospheres substantial enough to generate weather; all have impact craters and tectonic surface features, such as rift valleys and volcanoes. The term inner planet should not be confused with inferior planet, which designates those planets that are closer to the Sun than Earth is (i.e. Mercury and Venus).

Mercury

- Mercury (0.4 AU from the Sun) is the closest planet to the Sun and the smallest planet in the Solar System (0.055 Earth masses). Mercury has no natural satellites; besides impact craters, its only known geological features are lobed ridges or rupes, probably produced by a period of contraction early in its history.[67] Mercury's almost negligible atmosphere consists of atoms blasted off its surface by the solar wind.[68] Its relatively large iron core and thin mantle have not yet been adequately explained. Hypotheses include that its outer layers were stripped off by a giant impact; or, that it was prevented from fully accreting by the young Sun's energy.[69][70]

Venus

- Venus (0.7 AU from the Sun) is close in size to Earth (0.815 Earth masses) and, like Earth, has a thick silicate mantle around an iron core, a substantial atmosphere, and evidence of internal geological activity. It is much drier than Earth, and its atmosphere is ninety times as dense. Venus has no natural satellites. It is the hottest planet, with surface temperatures over 400 °C (752°F), most likely due to the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.[71] No definitive evidence of current geological activity has been detected on Venus, but it has no magnetic field that would prevent depletion of its substantial atmosphere, which suggests that its atmosphere is frequently replenished by volcanic eruptions.[72]

Earth

- Earth (1 AU from the Sun) is the largest and densest of the inner planets, the only one known to have current geological activity, and the only place where life is known to exist.[73] Its liquid hydrosphere is unique among the terrestrial planets, and it is the only planet where plate tectonics has been observed. Earth's atmosphere is radically different from those of the other planets, having been altered by the presence of life to contain 21% free oxygen.[74] It has one natural satellite, the Moon, the only large satellite of a terrestrial planet in the Solar System.

Mars

- Mars (1.5 AU from the Sun) is smaller than Earth and Venus (0.107 Earth masses). It possesses an atmosphere of mostly carbon dioxide with a surface pressure of 6.1 millibars (roughly 0.6% of that of Earth).[75] Its surface, peppered with vast volcanoes, such as Olympus Mons, and rift valleys, such as Valles Marineris, shows geological activity that may have persisted until as recently as 2 million years ago.[76] Its red colour comes from iron oxide (rust) in its soil.[77] Mars has two tiny natural satellites (Deimos and Phobos) thought to be captured asteroids.[78]

Asteroid belt

Main article: Asteroid belt

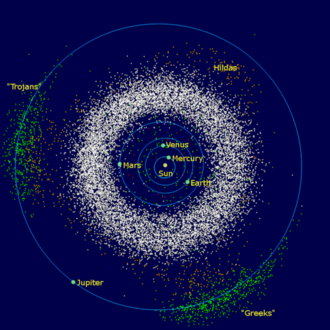

Image of the asteroid belt (white), the Jupiter trojans (green), the Hildas (orange), and near-Earth asteroids.

Asteroids are small Solar System bodies[d] composed mainly of refractory rocky and metallic minerals, with some ice.[79]

The asteroid belt occupies the orbit between Mars and Jupiter, between 2.3 and 3.3 AU from the Sun. It is thought to be remnants from the Solar System's formation that failed to coalesce because of the gravitational interference of Jupiter.[80]

Asteroids range in size from hundreds of kilometres across to microscopic. All asteroids except the largest, Ceres, are classified as small Solar System bodies.[81]

The asteroid belt contains tens of thousands, possibly millions, of objects over one kilometre in diameter.[82] Despite this, the total mass of the asteroid belt is unlikely to be more than a thousandth of that of Earth.[16] The asteroid belt is very sparsely populated; spacecraft routinely pass through without incident. Asteroids with diameters between 10 and 10−4 m are called meteoroids.[83]

Ceres

Ceres (2.77 AU) is the largest asteroid, a protoplanet, and a dwarf planet.[d] It has a diameter of slightly under 1,000 km, and a mass large enough for its own gravity to pull it into a spherical shape. Ceres was considered a planet when it was discovered in 1801, and was reclassified to asteroid in the 1850s as further observations revealed additional asteroids.[84] It was classified as a dwarf planet in 2006.Asteroid groups

Asteroids in the asteroid belt are divided into asteroid groups and families based on their orbital characteristics. Asteroid moons are asteroids that orbit larger asteroids. They are not as clearly distinguished as planetary moons, sometimes being almost as large as their partners. The asteroid belt also contains main-belt comets, which may have been the source of Earth's water.[85]Jupiter trojans are located in either of Jupiter's L4 or L5 points (gravitationally stable regions leading and trailing a planet in its orbit); the term "trojan" is also used for small bodies in any other planetary or satellite Lagrange point. Hilda asteroids are in a 2:3 resonance with Jupiter; that is, they go around the Sun three times for every two Jupiter orbits.[86]

The inner Solar System is also dusted with rogue asteroids, many of which cross the orbits of the inner planets.[87]

Outer Solar System

The outer region of the Solar System is home to the gas giants and their large moons. Many short-period comets, including the centaurs, also orbit in this region. Due to their greater distance from the Sun, the solid objects in the outer Solar System contain a higher proportion of volatiles, such as water, ammonia and methane, than the rocky denizens of the inner Solar System because the colder temperatures allow these compounds to remain solid.Outer planets

The four outer planets, or gas giants (sometimes called Jovian planets), collectively make up 99% of the mass known to orbit the Sun.[f] Jupiter and Saturn are each many tens of times the mass of Earth and consist overwhelmingly of hydrogen and helium; Uranus and Neptune are far less massive (<20 and="" astronomers="" belong="" category="" class="reference" earth="" for="" giants="" ice="" ices="" id="cite_ref-94" in="" makeup.="" masses="" more="" own="" possess="" reasons="" some="" suggest="" sup="" their="" these="" they="">[88]

Jupiter

- Jupiter (5.2 AU), at 318 Earth masses, is 2.5 times the mass of all the other planets put together. It is composed largely of hydrogen and helium. Jupiter's strong internal heat creates semi-permanent features in its atmosphere, such as cloud bands and the Great Red Spot.

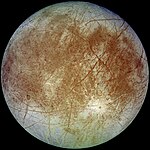

- Jupiter has 67 known satellites. The four largest, Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa, show similarities to the terrestrial planets, such as volcanism and internal heating.[89] Ganymede, the largest satellite in the Solar System, is larger than Mercury.

Saturn

- Saturn (9.5 AU), distinguished by its extensive ring system, has several similarities to Jupiter, such as its atmospheric composition and magnetosphere. Although Saturn has 60% of Jupiter's volume, it is less than a third as massive, at 95 Earth masses, making it the least dense planet in the Solar System.[90] The rings of Saturn are made up of small ice and rock particles.

- Saturn has 62 confirmed satellites; two of which, Titan and Enceladus, show signs of geological activity, though they are largely made of ice.[91] Titan, the second-largest moon in the Solar System, is larger than Mercury and the only satellite in the Solar System with a substantial atmosphere.

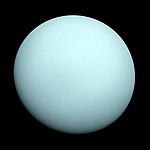

Uranus

- Uranus (19.2 AU), at 14 Earth masses, is the lightest of the outer planets. Uniquely among the planets, it orbits the Sun on its side; its axial tilt is over ninety degrees to the ecliptic. It has a much colder core than the other gas giants and radiates very little heat into space.[92]

- Uranus has 27 known satellites, the largest ones being Titania, Oberon, Umbriel, Ariel, and Miranda.

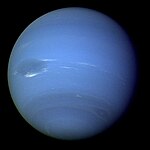

Neptune

- Neptune (30 AU), though slightly smaller than Uranus, is more massive (equivalent to 17 Earths) and therefore more dense. It radiates more internal heat, but not as much as Jupiter or Saturn.[93]

- Neptune has 14 known satellites. The largest, Triton, is geologically active, with geysers of liquid nitrogen.[94] Triton is the only large satellite with a retrograde orbit. Neptune is accompanied in its orbit by several minor planets, termed Neptune trojans, that are in 1:1 resonance with it.

Centaurs

The centaurs are icy comet-like bodies whose orbits have semi-major axes greater than Jupiter's (5.5 AU) and less than Neptune's (30 AU). The largest known centaur, 10199 Chariklo, has a diameter of about 250 km.[95] The first centaur discovered, 2060 Chiron, has also been classified as comet (95P) because it develops a coma just as comets do when they approach the Sun.[96]Comets

Comets are small Solar System bodies,[d] typically only a few kilometres across, composed largely of volatile ices. They have highly eccentric orbits, generally a perihelion within the orbits of the inner planets and an aphelion far beyond Pluto. When a comet enters the inner Solar System, its proximity to the Sun causes its icy surface to sublimate and ionise, creating a coma: a long tail of gas and dust often visible to the naked eye.

Short-period comets have orbits lasting less than two hundred years. Long-period comets have orbits lasting thousands of years. Short-period comets are believed to originate in the Kuiper belt, whereas long-period comets, such as Hale–Bopp, are believed to originate in the Oort cloud. Many comet groups, such as the Kreutz Sungrazers, formed from the breakup of a single parent.[97] Some comets with hyperbolic orbits may originate outside the Solar System, but determining their precise orbits is difficult.[98] Old comets that have had most of their volatiles driven out by solar warming are often categorised as asteroids.[99]

Trans-Neptunian region

The area beyond Neptune, or the "trans-Neptunian region", is still largely unexplored. It appears to consist overwhelmingly of small worlds (the largest having a diameter only a fifth that of Earth and a mass far smaller than that of the Moon) composed mainly of rock and ice. This region is sometimes known as the "outer Solar System", though others use that term to mean the region beyond the asteroid belt.Kuiper belt

The Kuiper belt is a great ring of debris similar to the asteroid belt, but consisting mainly of objects composed primarily of ice.[100] It extends between 30 and 50 AU from the Sun. Though it is estimated to contain anything from dozens to thousands of dwarf planets, it is composed mainly of small Solar System bodies. Many of the larger Kuiper belt objects, such as Quaoar, Varuna, and Orcus, may prove to be dwarf planets with further data. There are estimated to be over 100,000 Kuiper belt objects with a diameter greater than 50 km, but the total mass of the Kuiper belt is thought to be only a tenth or even a hundredth the mass of Earth.[15] Many Kuiper belt objects have multiple satellites,[101] and most have orbits that take them outside the plane of the ecliptic.[102]

The Kuiper belt can be roughly divided into the "classical" belt and the resonances.[100] Resonances are orbits linked to that of Neptune (e.g. twice for every three Neptune orbits, or once for every two). The first resonance begins within the orbit of Neptune itself. The classical belt consists of objects having no resonance with Neptune, and extends from roughly 39.4 AU to 47.7 AU.[103] Members of the classical Kuiper belt are classified as cubewanos, after the first of their kind to be discovered, (15760) 1992 QB1, and are still in near primordial, low-eccentricity orbits.[104]

Pluto and Charon

The dwarf planet Pluto (39 AU average) is the largest known object in the Kuiper belt. When discovered in 1930, it was considered to be the ninth planet; this changed in 2006 with the adoption of a formal definition of planet. Pluto has a relatively eccentric orbit inclined 17 degrees to the ecliptic plane and ranging from 29.7 AU from the Sun at perihelion (within the orbit of Neptune) to 49.5 AU at aphelion.

Charon, Pluto's largest moon, is sometimes described as part of a binary system with Pluto, as the two bodies orbit a barycentre of gravity above their surfaces (i.e. they appear to "orbit each other"). Beyond Charon, four much smaller moons, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra, are known to orbit within the system.

Pluto has a 3:2 resonance with Neptune, meaning that Pluto orbits twice round the Sun for every three Neptunian orbits. Kuiper belt objects whose orbits share this resonance are called plutinos.[105]

Makemake and Haumea

Makemake (45.79 AU average), although smaller than Pluto, is the largest known object in the classical Kuiper belt (that is, it is not in a confirmed resonance with Neptune). Makemake is the brightest object in the Kuiper belt after Pluto. It was named and designated a dwarf planet in 2008.[7] Its orbit is far more inclined than Pluto's, at 29°.[106]Haumea (43.13 AU average) is in an orbit similar to Makemake except that it is caught in a 7:12 orbital resonance with Neptune.[107] It is about the same size as Makemake and has two natural satellites. A rapid, 3.9-hour rotation gives it a flattened and elongated shape. It was named and designated a dwarf planet in 2008.[108]

Scattered disc

The scattered disc, which overlaps the Kuiper belt but extends much further outwards, is thought to be the source of short-period comets. Scattered disc objects are believed to have been ejected into erratic orbits by the gravitational influence of Neptune's early outward migration. Most scattered disc objects (SDOs) have perihelia within the Kuiper belt but aphelia far beyond it (some more than 150 AU from the Sun). SDOs' orbits are also highly inclined to the ecliptic plane and are often almost perpendicular to it. Some astronomers consider the scattered disc to be merely another region of the Kuiper belt and describe scattered disc objects as "scattered Kuiper belt objects".[109] Some astronomers also classify centaurs as inward-scattered Kuiper belt objects along with the outward-scattered residents of the scattered disc.[110]Eris

Eris (68 AU average) is the largest known scattered disc object, and caused a debate about what constitutes a planet, because it is 25% more massive than Pluto[111] and about the same diameter. It is the most massive of the known dwarf planets. It has one known moon, Dysnomia. Like Pluto, its orbit is highly eccentric, with a perihelion of 38.2 AU (roughly Pluto's distance from the Sun) and an aphelion of 97.6 AU, and steeply inclined to the ecliptic plane.Farthest regions

The point at which the Solar System ends and interstellar space begins is not precisely defined because its outer boundaries are shaped by two separate forces: the solar wind and the Sun's gravity. The outer limit of the solar wind's influence is roughly four times Pluto's distance from the Sun; this heliopause is considered the beginning of the interstellar medium.[56] The Sun's Hill sphere, the effective range of its gravitational dominance, is believed to extend up to a thousand times farther.[112]Heliopause

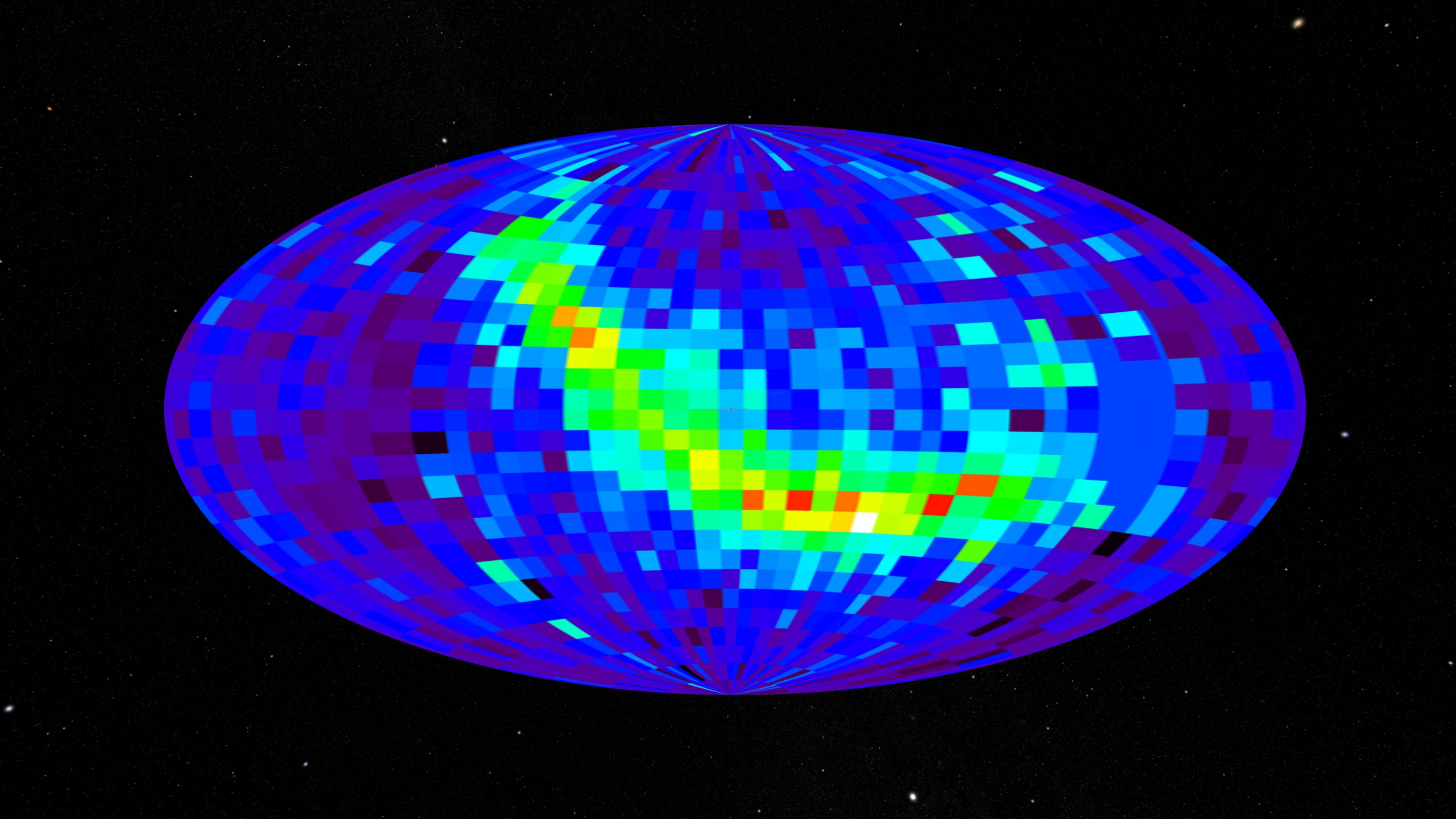

Energetic neutral atoms map of heliosheath and heliopause by IBEX. Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio.

The heliosphere is divided into two separate regions. The solar wind travels at roughly 400 km/s until it collides with the interstellar wind; the flow of plasma in the interstellar medium. The collision occurs at the termination shock, which is roughly 80–100 AU from the Sun upwind of the interstellar medium and roughly 200 AU from the Sun downwind.[113] Here the wind slows dramatically, condenses, and becomes more turbulent,[113] forming a great oval structure known as the heliosheath.

This structure is believed to look and behave very much like a comet's tail, extending outward for a further 40 AU on the upwind side but tailing many times that distance downwind; evidence from the Cassini and Interstellar Boundary Explorer spacecraft has suggested that it is forced into a bubble shape by the constraining action of the interstellar magnetic field.[114] The outer boundary of the heliosphere, the heliopause, is the point at which the solar wind finally terminates and is the beginning of interstellar space.[56] Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are reported to have passed the termination shock and entered the heliosheath, at 94 and 84 AU from the Sun, respectively.[115][116] Voyager 1 is reported to have crossed the heliopause in August, 2012.[117]

The shape and form of the outer edge of the heliosphere is likely affected by the fluid dynamics of interactions with the interstellar medium[113] as well as solar magnetic fields prevailing to the south, e.g. it is bluntly shaped with the northern hemisphere extending 9 AU farther than the southern hemisphere. Beyond the heliopause, at around 230 AU, lies the bow shock, a plasma "wake" left by the Sun as it travels through the Milky Way.[118]

Due to a lack of data, the conditions in local interstellar space are not known for certain. It is expected that NASA's Voyager spacecraft, as they pass the heliopause, will transmit valuable data on radiation levels and solar wind back to Earth.[119] How well the heliosphere shields the Solar System from cosmic rays is poorly understood. A NASA-funded team has developed a concept of a "Vision Mission" dedicated to sending a probe to the heliosphere.[120][121]

Detached objects

90377 Sedna (520 AU average) is a large, reddish object with a gigantic, highly elliptical orbit that takes it from about 76 AU at perihelion to 940 AU at aphelion and takes 11,400 years to complete. Mike Brown, who discovered the object in 2003, asserts that it cannot be part of the scattered disc or the Kuiper belt as its perihelion is too distant to have been affected by Neptune's migration. He and other astronomers consider it to be the first in an entirely new population, sometimes termed "distant detached objects" (DDOs), which also may include the object 2000 CR105, which has a perihelion of 45 AU, an aphelion of 415 AU, and an orbital period of 3,420 years.[122] Brown terms this population the "inner Oort cloud" because it may have formed through a similar process, although it is far closer to the Sun.[123] Sedna is very likely a dwarf planet, though its shape has yet to be determined. The second unequivocally detached object, with a perihelion farther than Sedna's at roughly 81 AU, is 2012 VP113, discovered in 2012. Its aphelion is only half that of Sedna's, at 400–500 AU.[124][125]Oort cloud

The Oort cloud is a hypothetical spherical cloud of up to a trillion icy objects that is believed to be the source for all long-period comets and to surround the Solar System at roughly 50,000 AU (around 1 light-year (ly)), and possibly to as far as 100,000 AU (1.87 ly). It is believed to be composed of comets that were ejected from the inner Solar System by gravitational interactions with the outer planets. Oort cloud objects move very slowly, and can be perturbed by infrequent events, such as collisions, the gravitational effects of a passing star, or the galactic tide, the tidal force exerted by the Milky Way.[126][127]

Boundaries

Much of the Solar System is still unknown. The Sun's gravitational field is estimated to dominate the gravitational forces of surrounding stars out to about two light years (125,000 AU). Lower estimates for the radius of the Oort cloud, by contrast, do not place it farther than 50,000 AU.[128] Despite discoveries such as Sedna, the region between the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud, an area tens of thousands of AU in radius, is still virtually unmapped. There are also ongoing studies of the region between Mercury and the Sun.[129] Objects may yet be discovered in the Solar System's uncharted regions.Galactic context

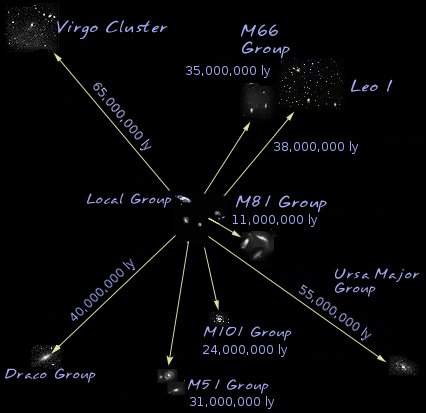

The Solar System is located in the Milky Way, a barred spiral galaxy with a diameter of about 100,000 light-years containing about 200 billion stars.[130] The Sun resides in one of the Milky Way's outer spiral arms, known as the Orion–Cygnus Arm or Local Spur.[131] The Sun lies between 25,000 and 28,000 light years from the Galactic Centre,[132] and its speed within the galaxy is about 220 kilometres per second (140 mi/s), so that it completes one revolution every 225–250 million years. This revolution is known as the Solar System's galactic year.[133] The solar apex, the direction of the Sun's path through interstellar space, is near the constellation Hercules in the direction of the current location of the bright star Vega.[134] The plane of the ecliptic lies at an angle of about 60° to the galactic plane.[g]

The Solar System's location in the galaxy is a factor in the evolution of life on Earth. Its orbit is close to circular, and orbits near the Sun are at roughly the same speed as that of the spiral arms. Therefore, the Sun passes through arms only rarely. Because spiral arms are home to a far larger concentration of supernovae, gravitational instabilities, and radiation that could disrupt the Solar System, this has given Earth long periods of stability for life to evolve.[136] The Solar System also lies well outside the star-crowded environs of the galactic centre. Near the centre, gravitational tugs from nearby stars could perturb bodies in the Oort Cloud and send many comets into the inner Solar System, producing collisions with potentially catastrophic implications for life on Earth. The intense radiation of the galactic centre could also interfere with the development of complex life.[136] Even at the Solar System's current location, some scientists have hypothesised that recent supernovae may have adversely affected life in the last 35,000 years by flinging pieces of expelled stellar core towards the Sun as radioactive dust grains and larger, comet-like bodies.[137]

Neighbourhood

Beyond the heliosphere is the interstellar medium, consisting of various clouds of gases. (see Local Interstellar Cloud)

The Solar System is currently located in the Local Interstellar Cloud or Local Fluff. It is thought to be near the neighbouring G-Cloud, but it is unknown if the Solar System is embedded in the Local Interstellar Cloud, or if it is in the region where the Local Interstellar Cloud and G-Cloud are interacting.[138][139] The Local Interstellar Cloud is an area of denser cloud in an otherwise sparse region known as the Local Bubble, an hourglass-shaped cavity in the interstellar medium roughly 300 light years across. The bubble is suffused with high-temperature plasma that suggests it is the product of several recent supernovae.[140]

There are relatively few stars within ten light years (95 trillion km, or 60 trillion mi) of the Sun. The closest is the triple star system Alpha Centauri, which is about 4.4 light years away. Alpha Centauri A and B are a closely tied pair of Sun-like stars, whereas the small red dwarf Alpha Centauri C (also known as Proxima Centauri) orbits the pair at a distance of 0.2 light years. The stars next closest to the Sun are the red dwarfs Barnard's Star (at 5.9 light years), Wolf 359 (7.8 light years), and Lalande 21185 (8.3 light years). The largest star within ten light years is Sirius, a bright main-sequence star roughly twice the Sun's mass and orbited by a white dwarf called Sirius B. It lies 8.6 light years away. The nearest brown dwarfs are the binary Luhman 16 system at 6.6 light years. The remaining systems within ten light years are the binary red-dwarf system Luyten 726-8 (8.7 light years) and the solitary red dwarf Ross 154 (9.7 light years).[141] The Solar System's closest solitary Sun-like star is Tau Ceti, which lies 11.9 light years away. It has roughly 80% of the Sun's mass but only 60% of its luminosity.[142] The closest known extrasolar planet to the Sun lies around Alpha Centauri B. Its one confirmed planet, Alpha Centauri Bb, is at least 1.1 times Earth's mass and orbits its star every 3.236 days.[143] The closest known free-floating planet to the Sun is WISE 0855–0714,[144] an object of less than 10 Jupiter masses located roughly 7 light years away.

Visual summary

This section is a sampling of Solar System bodies, selected for size and quality of imagery, and sorted by volume. Some omitted objects are larger than the ones included here, notably Pluto and Eris, because these have not been imaged in high quality. | ||||||

| Sun (star) | Jupiter (planet) | Saturn (planet) | Uranus (planet) | Neptune (planet) | Earth (planet) | Venus (planet) |

| Mars (planet) | Ganymede (moon of Jupiter) | Titan (moon of Saturn) | Mercury (planet) | Callisto (moon of Jupiter) | Io (moon of Jupiter) | Moon (moon of Earth) |

| Europa (moon of Jupiter) | Triton (moon of Neptune) | Titania (moon of Uranus) | Rhea (moon of Saturn) | Oberon (moon of Uranus) | Iapetus (moon of Saturn) | Umbriel (moon of Uranus) |

| Ariel (moon of Uranus) | Dione (moon of Saturn) | Tethys (moon of Saturn) | Ceres (dwarf planet) | Vesta (asteroid) | Enceladus (moon of Saturn) | Miranda (moon of Uranus) |

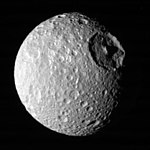

| Proteus (moon of Neptune) | Mimas (moon of Saturn) | Hyperion (moon of Saturn) | Phoebe (moon of Saturn) | Janus (moon of Saturn) | Epimetheus (moon of Saturn) | Prometheus (moon of Saturn) |