From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

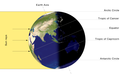

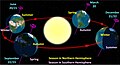

Occurrence of terrestrial auroras

Most auroras occur in a band known as the auroral zone[2] which is typically 3° to 6° wide in latitude and between 10° and 20° from the geomagnetic poles at all local times (or longitudes), most clearly seen at night against a dark sky. A region displaying an aurora at any given time is known as the auroral oval, a band which is displaced towards the nightside of the Earth. The day-to-day positions of the auroral ovals are posted on the internet.[3] A geomagnetic storm causes the auroral ovals (north and south) to expand, and bring the aurora to lower latitudes. Early evidence for a geomagnetic connection comes from the statistics of auroral observations. Elias Loomis (1860) and later in more detail Hermann Fritz (1881)[4] and S. Tromholt (1882)[5] established that the aurora appeared mainly in the "auroral zone", a ring-shaped region with a radius of approximately 2500 km around the Earth's magnetic pole. It was hardly ever seen near the geographic pole, which is about 2000 km away from the magnetic pole. The instantaneous distribution of auroras ("auroral oval")[2] is slightly different, being centered about 3–5 degrees nightward of the magnetic pole, so that auroral arcs reach furthest toward the equator when the magnetic pole in question is in between the observer and the Sun. The aurora can be seen best at this time, which is called magnetic midnight.In northern latitudes, the effect is known as the aurora borealis (or the northern lights), named after the Roman goddess of dawn, Aurora, and the Greek name for the north wind, Boreas, by Galileo in 1619.[6] Auroras seen within the auroral oval may be directly overhead, but from farther away they illuminate the poleward horizon as a greenish glow, or sometimes a faint red, as if the Sun were rising from an unusual direction. Its southern counterpart, the aurora australis (or the southern lights), has features that are almost identical to the aurora borealis and changes simultaneously with changes in the northern auroral zone.[7] It is visible from high southern latitudes in Antarctica, South America, New Zealand, and Australia. Auroras also occur on other planets. Similar to the Earth's aurora, they are also visible close to the planets’ magnetic poles. Auroras also occur poleward of the auroral zone as either diffuse patches or arcs,[8] which can be sub-visual.

North America

11. These NOAA maps of North America and Eurasia show the local midnight equatorward boundary of the aurora at different levels of geomagnetic activity; a Kp=3 corresponds to low levels of geomagnetic activity, while Kp=9 represents high levels

Auroras are occasionally seen in latitudes below the auroral zone, when a geomagnetic storm temporarily enlarges the auroral oval. Large geomagnetic storms are most common during the peak of the eleven-year sunspot cycle or during the three years after the peak.[9][10] An aurora may appear overhead as a "corona" of rays, radiating from a distant and apparent central location, which results from perspective. An electron spirals (gyrates) about a field line at an angle that is determined by its velocity vectors, parallel and perpendicular, respectively, to the local geomagnetic field vector B. This angle is known as the “pitch angle” of the particle. The distance, or radius, of the electron from the field line at any time is known as its Larmor radius. The pitch angle increases as the electron travels to a region of greater field strength nearer to the atmosphere. Thus it is possible for some particles to return, or mirror, if the angle becomes 90 degrees before entering the atmosphere to collide with the denser molecules there. Other particles, that do not mirror will enter the atmosphere and contribute to the auroral display over a range of altitudes. Other types of auroras have been observed from space, e.g."poleward arcs" stretching sunward across the polar cap, the related "theta aurora",[11] and "dayside arcs" near noon. These are relatively infrequent and poorly understood. There are other interesting effects such as flickering aurora, "black aurora" and sub-visual red arcs. In addition to all these, a weak glow (often deep red) observed around the two polar cusps, the field lines separating the ones that close through the Earth from those that are swept into the tail and close remotely.

Images

The altitudes at which auroral emissions occur were revealed by Carl Størmer and his colleagues who used cameras to triangulate more than 12,000 auroras.[12] They discovered that most of the light is produced between 90 and 150 km above the ground, while extending at times to more than 1000 km. Images of auroras are significantly more common today than in the past due to the increase in use of digital cameras that have high enough sensitivities.[13] Film and digital exposure to auroral displays is fraught with difficulties, particularly if faithfulness of reproduction is an objective. Due to the different colour spectrum present, and the temporal changes occurring during the exposure, the results are somewhat unpredictable. Different layers of the film emulsion respond differently to lower light levels, and choice of film can be very important. Longer exposures superimpose rapidly changing features, and often blanket the dynamic attribute of a display. Higher sensitivity creates issues with graininess.

The aurora frequently appears either as a diffuse glow or as "curtains" that extend approximately in the east-west direction. At some times, they form "quiet arcs"; at others ("active aurora"), they evolve and change constantly. Each curtain consists of many parallel rays, each lined up with the local direction of the magnetic field, consistent with auroras being shaped by Earth's magnetic field. In-situ particle measurements confirm that auroral electrons are guided by the geomagnetic field, and spiral around them while moving toward Earth. The similarity of an auroral display to curtains is often enhanced by folds within the arcs.

David Malin pioneered multiple exposure using multiple filters for astronomical photography, recombining the images in the laboratory to recreate the visual display more accurately.[14] For scientific research, proxies are often used, such as ultra-violet, and colour-correction to simulate the appearance to humans. Predictive techniques are also used, to indicate the extent of the display, a highly useful tool for aurora hunters.[15] Terrestrial features often find their way into aurora images, making them more accessible and more likely to be published by major websites.[16] It is possible to take excellent images with standard film (using ISO ratings between 100 and 400) and a single-lens reflex camera with full aperture, a fast lens (f1.4 50 mm, for example), and exposures between 10 and 30 seconds, depending on the aurora's brightness.[17]

Early work on the imaging of the auroras was done in 1949 by the University of Saskatchewan using the SCR-270 radar.

-

Aurora borealis from the International Space Station

-

Aurora during a geomagnetic storm that was most likely caused by a coronal mass ejection from the Sun on 24 May 2010. Taken from the ISS

Visual forms & colours

Auroras take many different visual forms. The most distinctive and brightest are the curtain-like auroral arcs. They eventually fragment or ‘break-up’ into separate, and rapidly changing, often rayed features which may fill the whole sky. These are the ‘discrete’ auroras which are at times bright enough to read a newspaper by at night.[18] The ‘diffuse’ aurora, on the other hand, is a relatively featureless glow sometimes close to the limit of visibility.[19] It can be distinguished from moonlit clouds by the fact that stars can be seen undiminished through the glow. Diffuse auroras are often composed of patches whose brightness exhibits regular or near-regular pulsations. The pulsation period can be typically many seconds, so is not always obvious. Occasionally there is a fast, sub-second, flickering. A typical auroral display consists of these forms appearing in the above order throughout the night.[20]- Red: At the highest altitudes, excited atomic oxygen emits at 630.0 nm (red); low concentration of atoms and lower sensitivity of eyes at this wavelength make this colour visible only under more intense solar activity. The low amount of oxygen atoms and their gradually diminishing concentration is responsible for the faint appearance of the top parts of the "curtains".

- Green: At lower altitudes the more frequent collisions suppress this mode and the 557.7 nm emission (green) dominates; fairly high concentration of atomic oxygen and higher eye sensitivity in green make green auroras the most common. The excited molecular nitrogen (atomic nitrogen being rare due to high stability of the N2 molecule) plays its role here as well, as it can transfer energy by collision to an oxygen atom, which then radiates it away at the green wavelength. (Red and green can also mix together to produce pink or yellow hues.) The rapid decrease of concentration of atomic oxygen below about 100 km is responsible for the abrupt-looking end of the lower edges of the curtains.

- Yellow and pink are a mix of red and green or blue.

- Blue: At yet lower altitudes atomic oxygen is, uncommon, and ionized molecular nitrogen takes over in producing visible light emission; it radiates at a large number of wavelengths in both red and blue parts of the spectrum, with 428 nm (blue) being dominant. Blue and purple emissions, typically at the lower edges of the "curtains", show up at the highest levels of solar activity.[21]

Other auroral radiation

In addition, the aurora and associated currents produce a strong radio emission around 150 kHz known as auroral kilometric radiation AKR, discovered in 1972.[22] Ionospheric absorption makes AKR only observable from space. X-ray emissions, originating from the particles associated with auroras, have also been detected .[23]Causes of auroras

A full understanding of the physical processes which lead to different types of auroras is still incomplete, but the basic cause involves the interaction of the solar wind with the earth’s magnetosphere. The varying intensity of the solar wind produces effects of different magnitudes, but includes one or more of the following physical scenarios.- A quiescent solar wind flowing past the Earth’s magnetosphere steadily interacts with it and can both inject solar wind particles directly onto the geomagnetic field lines that are ‘open’, as opposed to being ‘closed’ in the opposite hemisphere, and provide diffusion through the bow shock. It can also cause particles already trapped in the radiation belts to precipitate into the atmosphere. Once particles are lost to the atmosphere from the radiation belts, under quiet conditions new ones replace them only slowly, and the loss-cone becomes depleted. In the magnetotail, however, particle trajectories seem constantly to reshuffle, probably when the particles cross the very weak magnetic field near the equator. As a result, the flow of electrons in that region is nearly the same in all directions ("isotropic"), and assures a steady supply of leaking electrons. The leakage of electrons does not leave the tail positively charged, because each leaked electron lost to the atmosphere is replaced by a low energy electron drawn upward from the ionosphere. Such replacement of "hot" electrons by "cold" ones is in complete accord with the 2nd law of thermodynamics. The complete process. which also generates an electric ring current around the earth, is uncertain.

- Geomagnetic disturbance from an enhanced solar wind causes distortions of the magnetotail ("magnetic substorms"). These ‘substorms’ tend to occur after prolonged spells (hours) during which the interplanetary magnetic field has had an appreciable southward component. This leads to a higher rate of interconnection between its field lines and those of Earth. As a result the solar wind moves magnetic flux (tubes of magnetic field lines, ‘locked’ together with their resident plasma) from the day side of Earth to the magnetotail, widening the obstacle it presents to the solar wind flow and constricting the tail on the night-side. Ultimately some tail plasma can separate ("magnetic reconnection"); some blobs ("plasmoids") are squeezed downstream and are carried away with the solar wind; others are squeezed toward Earth where their motion feeds strong outbursts of auroras, mainly around midnight ("unloading process"). A geomagnetic storm resulting from greater interaction adds many more particles to the plasma trapped around Earth, also producing enhancement of the "ring current". Occasionally the resulting modification of the Earth's magnetic field can be so strong that it produces auroras visible at middle latitudes, on field lines much closer to the equator than those of the auroral zone.

- Acceleration of auroral charged particles invariably accompanies a magnetospheric disturbance that causes an aurora. This mechanism, which is believed to predominantly arise from wave-particle interactions, raises the velocity of a particle in the direction of the guiding magnetic field. The pitch angle is thereby decreased, and increases the chance of it being precipitated into the atmosphere. Both electromagnetic and electrostatic waves, produced at the time of greater geomagnetic disturbances, make a significant contribution to the energising processes that enable an aurora to be sustained. Particle acceleration provides a complex intermediate process for transferring energy from the solar wind indirectly into the atmosphere.

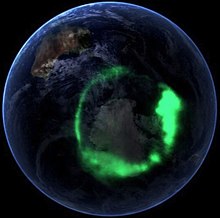

Aurora australis (11 September 2005) as captured by NASA's IMAGE satellite, digitally overlaid onto The Blue Marble composite image. An animation created using the same satellite data is also available

The details of these phenomena are not fully understood. However it is clear that the prime source of auroral particles is the solar wind feeding the magnetosphere, the reservoir containing the radiation zones, and temporarily magnetically trapped, particles confined by the geomagnetic field, coupled with particle acceleration processes.[24]

Auroral particles

The immediate cause of the ionization and excitation of atmospheric constituents leading to auroral emissions was discovered in 1960, with a pioneering rocket flight made from Fort Churchill in Canada, to be a flux of electrons entering the atmosphere from above.[25] Since then an extensive collection of measurements has been acquired painstakingly and with steadily improving resolution since the 1960s by many research teams using rockets and satellites to traverse the auroral zone. The main findings have been that auroral arcs and other bright forms are due to electrons which have been accelerated during the final few 10,000 km or so of their plunge into the atmosphere.[26] These electrons often, but not always, exhibit a peak in their energy distribution, and are preferentially aligned along the local direction of the magnetic field. The electrons which are mainly responsible for diffuse and pulsating auroras have, in contrast, a smoothly falling energy distribution, and an angular (pitch-angle) distribution favouring directions perpendicular to the local magnetic field. Pulsations were discovered to originate at or close to the equatorial crossing point of auroral zone magnetic field lines.[27] Protons are also associated with auroras, both discrete and diffuse.Auroras and the atmosphere

Auroras result from emissions of photons in the Earth's upper atmosphere, above 80 km (50 mi), from ionized nitrogen atoms regaining an electron, and oxygen atoms and nitrogen based molecules returning from an excited state to ground state.[28] They are ionized or excited by the collision of particles precipitated into the atmosphere. Both incoming electrons and protons may be involved. Excitation energy is lost within the atmosphere by the emission of a photon, or by collision with another atom or molecule:- oxygen emissions

- green or orange-red, depending on the amount of energy absorbed.

- nitrogen emissions

- blue or red; blue if the atom regains an electron after it has been ionized, red if returning to ground state from an excited state.

Auroras and the ionosphere

Bright auroras are generally associated with Birkeland currents (Schield et al., 1969;[29] Zmuda and Armstrong, 1973[30]) which flow down into the ionosphere on one side of the pole and out on the other. In between, some of the current connects directly through the ionospheric E layer (125 km); the rest ("region 2") detours, leaving again through field lines closer to the equator and closing through the "partial ring current" carried by magnetically trapped plasma. The ionosphere is an ohmic conductor, so some consider that such currents require a driving voltage, which an, as yet unspecified, dynamo mechanism can supply. Electric field probes in orbit above the polar cap suggest voltages of the order of 40,000 volts, rising up to more than 200,000 volts during intense magnetic storms. In another interpretation the currents are the direct result of electron acceleration into the atmosphere by wave/particle interactions.Ionospheric resistance has a complex nature, and leads to a secondary Hall current flow. By a strange twist of physics, the magnetic disturbance on the ground due to the main current almost cancels out, so most of the observed effect of auroras is due to a secondary current, the auroral electrojet. An auroral electrojet index (measured in nanotesla) is regularly derived from ground data and serves as a general measure of auroral activity. Kristian Birkeland[31] deduced that the currents flowed in the east-west directions along the auroral arc, and such currents, flowing from the dayside toward (approximately) midnight were later named "auroral electrojets" (see also Birkeland currents).

Interaction of the solar wind with Earth

The Earth is constantly immersed in the solar wind, a rarefied flow of hot plasma (a gas of free electrons and positive ions) emitted by the Sun in all directions, a result of the two-million-degree temperature of the Sun's outermost layer, the corona. The solar wind reaches Earth with a velocity typically around 400 km/s, a density of around 5 ions/cm3 and a magnetic field intensity of around 2–5 nT (nanoteslas; (for comparison, Earth's surface field is typically 30,000–50,000 nT). During magnetic storms, in particular, flows can be several times faster; the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) may also be much stronger. Joan Feynman deduced in the 1970s that the long-term averages of solar wind speed correlated with geomagnetic activity.[32] Her work resulted from data collected by the Explorer 33 spacecraft The solar wind and magnetosphere consist of plasma (ionized gas), which conducts electricity. It is well known (since Michael Faraday's work around 1830) that when an electrical conductor is placed within a magnetic field while relative motion occurs in a direction that the conductor cuts across (or is cut by), rather than along, the lines of the magnetic field, an electric current is induced within the conductor. The strength of the current depends on a) the rate of relative motion, b) the strength of the magnetic field, c) the number of conductors ganged together and d) the distance between the conductor and the magnetic field, while the direction of flow is dependent upon the direction of relative motion. Dynamos make use of this basic process ("the dynamo effect"), any and all conductors, solid or otherwise are so affected, including plasmas and other fluids. The IMF originates on the Sun, linked to the sunspots, and its field lines (lines of force) are dragged out by the solar wind. That alone would tend to line them up in the Sun-Earth direction, but the rotation of the Sun angles them at Earth by about 45 degrees forming a spiral in the ecliptic plane), known as the Parker spiral. The field lines passing Earth will therefore usually be linked to those near the western edge ("limb") of the visible Sun at any time.[33] The solar wind and the magnetosphere, being two electrically conducting fluids in relative motion, should be able in principle to generate electric currents by dynamo action and impart energy from the flow of the solar wind. However, this process is hampered by the fact that plasmas conduct readily along magnetic field lines, but less readily perpendicular to them. Energy is more effectively transferred by temporary magnetic connection between the field lines of the solar wind and those of the magnetosphere. Unsurprisingly this process is known as magnetic reconnection. As already mentioned, it happens most readily when the interplanetary field is directed southward, in a similar direction to the geomagnetic field in the inner regions of both the north magnetic pole and south magnetic pole.Auroras are more frequent and brighter during the intense phase of the solar cycle when coronal mass ejections increase the intensity of the solar wind.[34]

Magnetosphere

Earth's magnetosphere is shaped by the impact of the solar wind on the Earth's magnetic field which forms an obstacle to the flow, diverting it, at an average distance of about 70,000 km (11 Earth radii or Re),[35] producing a bow shock 12,000 km to 15,000 km (1.9 to 2.4 Re) further upstream. The width of the magnetosphere abreast of Earth, is typically 190,000 km (30 Re), and on the night side a long "magnetotail" of stretched field lines extends to great distances (> 200 Re). The high latitude magnetosphere is filled with plasma as the solar wind passes the Earth. The flow of plasma into the magnetosphere increases with additional turbulence, density and speed in the solar wind. This flow is favoured by a southward component of the IMF which can then directly connect to the high latitude geomagnetic field lines.[36] The flow pattern of magnetospheric plasma is mainly from the magnetotail toward the Earth, around the Earth and back into the solar wind through the magnetopause on the day-side. In addition to moving perpendicular to the Earth's magnetic field, some magnetospheric plasma travels down along the Earth's magnetic field lines, gains additional energy and loses it to the atmosphere in the auroral zones. The cusps of the magnetosphere, separating geomagnetic field lines that close through the Earth from those that close remotely allow a small amount of solar wind to directly reach the top of the atmosphere, producing an auroral glow.On 26 February 2008, THEMIS probes were able to determine, for the first time, the triggering event for the onset of magnetospheric substorms.[37] Two of the five probes, positioned approximately one third the distance to the moon, measured events suggesting a magnetic reconnection event 96 seconds prior to auroral intensification.[38]

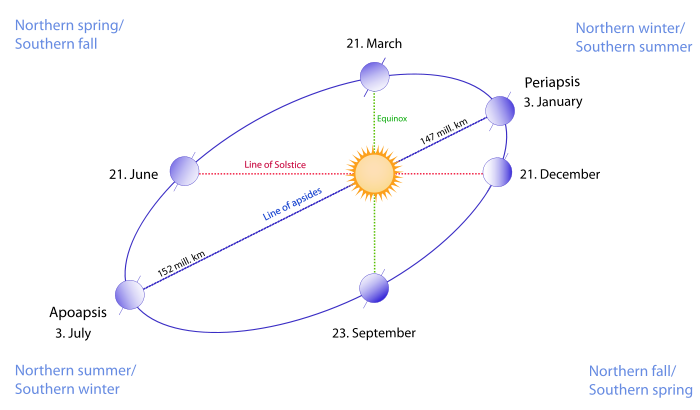

Geomagnetic storms that ignite auroras may occur more often during the months around the equinoxes. It is not well understood, but geomagnetic storms may vary with Earth's seasons. Two factors to consider are the tilt of both the solar and Earth’s axis to the ecliptic plane. As the Earth moves in its orbit throughout a year it will experience an interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) from different latitudes of the Sun, which is tilted at 8 degrees. Similarly, the 23 degree tilt of the Earth’s axis about which the geomagnetic pole rotates with a diurnal variation, changes the daily average angle that the geomagnetic field presents to the incident IMF throughout a year. These factors combined can lead to minor cyclical changes in the detailed way that the IMF links to the magnetosphere. In turn, this affects the average probability of opening a door through which energy from the solar wind can reach the Earth's inner magnetosphere and thereby enhance auroras.

Auroral particle acceleration

The electrons responsible for the brightest forms of aurora are well accounted for by their acceleration in the dynamic electric fields of plasma turbulence encountered during precipitation from the magnetosphere into the auroral atmosphere. In contrast, static electric fields are unable to transfer energy to the electrons due to their conservative nature.[39] The electrons and ions which cause the dim glow of the diffuse aurora appear not to be accelerated during precipitation . The convergence of magnetic field lines towards the Earth that creates a ‘magnetic mirror’ turns back many of the downward flowing electrons as the field strength increases. The bright forms of auroras are produced when downward acceleration not only increases the energy of precipitating electrons but also reduces their pitch angles (angle between electron velocity and the local magnetic field vector). This greatly increases the rate of deposition of energy into the atmosphere, and thereby the rates of ionisation, excitation and consequent auroral light emission. It also enhances the electric current. One early theory proposed for the acceleration of auroral electrons is based on an assumed static, or quasi-static, electric field and a consequent uni-directional potential drop.[40] The originating charge assembly and associated equi-potentials are so-far unspecified. However, Poisson’s equation indicates that there can be no configuration of charge resulting in a net potential drop. This fact prohibits the concept of a uni-directional potential drop. The electric field theory proposed for auroral particle acceleration is therefore highly questionable as it appears to violate a basic principle of physics. A more credible theory is based on acceleration by Landau [41] resonance in the turbulent electric fields of the acceleration region. This process is essentially the same as that employed in plasma fusion laboratories throughout the world,[42] and appears well able to account in principle for most – if not all – detailed properties of the electrons responsible for the brightest forms of aurorae, above, below and within the acceleration region.[43]Other mechanisms have also been proposed, in particular, Alfvén waves, wave modes involving the magnetic field first noted by Hannes Alfvén (1942), which have been observed in the laboratory and in space. The question is whether these waves might just be a different way of looking at the above process, however, because this approach does not point out a different energy source, and many plasma bulk phenomena can also be described in terms of Alfvén waves.

Other processes are also involved in the aurora, and much remains to be learned. Auroral electrons created by large geomagnetic storms often seem to have energies below 1 keV, and are stopped higher up, near 200 km. Such low energies excite mainly the red line of oxygen, so that often such auroras are red. On the other hand, positive ions also reach the ionosphere at such time, with energies of 20–30 keV, suggesting they might be an "overflow" along magnetic field lines of the copious "ring current" ions accelerated at such times, by processes different from the ones described above. Some O+ ions ("conics") also seem accelerated in different ways by plasma processes associated with the aurora. These ions are accelerated by plasma waves in directions mainly perpendicular to the field lines. They therefore start at their "mirror points" and can travel only upward. As they do so, the "mirror effect" transforms their directions of motion, from perpendicular to the field line to a cone around it, which gradually narrows down, becoming increasingly parallel at large distances where the field is much weaker.

Auroral events of historical significance

The auroras that resulted from the "great geomagnetic storm" on both 28 August and 2 September 1859 are thought to be the most spectacular in recent recorded history. In a paper to the Royal Society on 21 November 1861, Balfour Stewart described both auroral events as documented by a self-recording magnetograph at the Kew Observatory and established the connection between the 2 September 1859 auroral storm and the Carrington-Hodgson flare event when he observed that, "It is not impossible to suppose that in this case our luminary was taken in the act."[44] The second auroral event, which occurred on 2 September 1859 as a result of the exceptionally intense Carrington-Hodgson white light solar flare on 1 September 1859, produced auroras, so widespread and extraordinarily bright, that they were seen and reported in published scientific measurements, ship logs, and newspapers throughout the United States, Europe, Japan, and Australia. It was reported by the New York Times that in Boston on Friday 2 September 1859 the aurora was "so brilliant that at about one o'clock ordinary print could be read by the light".[45] One o'clock EST time on Friday 2 September, would have been 6:00 GMT and the self-recording magnetograph at the Kew Observatory was recording the geomagnetic storm, which was then one hour old, at its full intensity. Between 1859 and 1862, Elias Loomis published a series of nine papers on the Great Auroral Exhibition of 1859 in the American Journal of Science where he collected world-wide reports of the auroral event.That aurora is thought to have been produced by one of the most intense coronal mass ejections in history. It is also notable for the fact that it is the first time where the phenomena of auroral activity and electricity were unambiguously linked. This insight was made possible not only due to scientific magnetometer measurements of the era, but also as a result of a significant portion of the 125,000 miles (201,000 km) of telegraph lines then in service being significantly disrupted for many hours throughout the storm. Some telegraph lines, however, seem to have been of the appropriate length and orientation to produce a sufficient geomagnetically induced current from the electromagnetic field to allow for continued communication with the telegraph operator power supplies switched off. The following conversation occurred between two operators of the American Telegraph Line between Boston and Portland, Maine, on the night of 2 September 1859 and reported in the Boston Traveler:

Boston operator (to Portland operator): "Please cut off your battery [power source] entirely for fifteen minutes."The conversation was carried on for around two hours using no battery power at all and working solely with the current induced by the aurora, and it was said that this was the first time on record that more than a word or two was transmitted in such manner.[45] Such events led to the general conclusion that

Portland operator: "Will do so. It is now disconnected."

Boston: "Mine is disconnected, and we are working with the auroral current. How do you receive my writing?"

Portland: "Better than with our batteries on. – Current comes and goes gradually."

Boston: "My current is very strong at times, and we can work better without the batteries, as the aurora seems to neutralize and augment our batteries alternately, making current too strong at times for our relay magnets. Suppose we work without batteries while we are affected by this trouble."

Portland: "Very well. Shall I go ahead with business?"

Boston: "Yes. Go ahead."

The effect of the aurorae on the electric telegraph is generally to increase or diminish the electric current generated in working the wires. Sometimes it entirely neutralizes them, so that, in effect, no fluid is discoverable in them. The aurora borealis seems to be composed of a mass of electric matter, resembling in every respect, that generated by the electric galvanic battery. The currents from it change coming on the wires, and then disappear: the mass of the aurora rolls from the horizon to the zenith.[46]

Historical theories, superstition & mythology

Magnetic control of the aurora was mentioned by Ancient Greek explorer/geographer Pytheas, Hiorter, and Celsius described in 1741 evidence that large magnetic fluctuations occurred whenever the aurora was observed overhead. It was also later realized that large electric currents were associated with the aurora, flowing in the region where auroral light originated.

Multiple superstitions and obsolete theories explaining the aurora have emerged over the centuries.

- Seneca speaks diffusely on auroras in the first book of his Naturales Quaestiones, drawing mainly from Aristotle; he classifies them "putei" or wells when they are circular and "rim a large hole in the sky", "pithaei" when they look like casks, "chasmata" from the same root of the English chasm, "pogoniae" when they are bearded, "cyparissae" when they look like cypresses), describes their manifold colors and asks himself whether they are above or below the clouds. He recalls that under Tiberius, an aurora formed above Ostia, so intense and so red that a cohort of the army, stationed nearby for fireman duty, galloped to the city.

- Walter William Bryant wrote in his book Kepler (1920) that Tycho Brahe "seems to have been something of a homœopathist, for he recommends sulfur to cure infectious diseases “brought on by the sulphurous vapours of the Aurora Borealis."[47]

- Benjamin Franklin theorized that the "mystery of the Northern Lights" was caused by a concentration of electrical charges in the polar regions intensified by the snow and other moisture.[48]

There is the claim from 1855 that in Norse mythology:

The Valkyrior are warlike virgins, mounted upon horses and armed with helmets and spears. /.../ When they ride forth on their errand, their armour sheds a strange flickering light, which flashes up over the northern skies, making what Men call the "aurora borealis", or "Northern Lights".[50]While a striking notion, there is not a vast body of evidence in the Old Norse literature giving this interpretation, or even much reference to auroras. Although auroral activity is common over Scandinavia and Iceland today, it is possible that the Magnetic North Pole was considerably farther away from this region during the relevant period of Norse mythology.[51]

The first Old Norse account of norðrljós is found in the Norwegian chronicle Konungs Skuggsjá from AD 1230. The chronicler has heard about this phenomenon from compatriots returning from Greenland, and he gives three possible explanations: that the ocean was surrounded by vast fires, that the sun flares could reach around the world to its night side, or that glaciers could store energy so that they eventually became fluorescent.[52]

In ancient Roman mythology, Aurora is the goddess of the dawn, renewing herself every morning to fly across the sky, announcing the arrival of the sun. The persona of Aurora the goddess has been incorporated in the writings of Shakespeare, Lord Tennyson, and Thoreau.

In the traditions of Aboriginal Australians, the Aurora Australis is commonly associated with fire. For example, the Gunditjmara people of western Victoria called auroras "Puae buae", meaning "ashes", while the Gunai people of eastern Victoria perceived auroras as bushfires in the spirit world. When the Dieri people of South Australia said that an auroral display was "Kootchee", an evil spirit creating a large fire. Similarly, the Ngarrindjeri people of South Australia referred to auroras seen over Kangaroo Island as the campfires of spirits in the ‘Land of the Dead’. Aboriginal people in southwest Queensland believed the auroras to be the fires of the "Oola Pikka", ghostly spirits who spoke to the people through auroras. Sacred law forbade anyone except male elders from watching or interpreting the messages of ancestors they believed were transmitted through auroras.[53]

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the lights could be seen from the battlefield that night. The Confederate Army took it as a sign that God was on their side during the battle as it was very rare that one could see the Lights in Virginia. The painting Aurora Borealis (see Aurora Borealis) (1865) by American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church is widely interpreted to represent the conflict of the American Civil War.[54]

Planetary auroras

An aurora high above the northern part of Saturn; image taken by the Cassini spacecraft, a movie (click on image), shows images from 81 hours of observations of Saturn's aurora

Both Jupiter and Saturn have magnetic fields much stronger than Earth's (Jupiter's equatorial field strength is 4.3 gauss, compared to 0.3 gauss for Earth), and both have extensive radiation belts. Auroras have been observed on both, most clearly with the Hubble Space Telescope. Uranus and Neptune have also been observed to have auroras.[55]

The auroras on the gas giants seem, like Earth's, to be powered by the solar wind. In addition, however, Jupiter's moons, especially Io, are powerful sources of auroras on Jupiter. These arise from electric currents along field lines ("field aligned currents"), generated by a dynamo mechanism due to the relative motion between the rotating planet and the moving moon. Io, which has active volcanism and an ionosphere, is a particularly strong source, and its currents also generate radio emissions, studied since 1955. Auroras also have been observed on the surfaces of Io, Europa, and Ganymede, using the Hubble Space Telescope. These auroras have also been observed on Venus and Mars. Because Venus has no intrinsic (planetary) magnetic field, Venusian auroras appear as bright and diffuse patches of varying shape and intensity, sometimes distributed across the full planetary disc. Venusian auroras are produced by the impact of electrons originating from the solar wind and precipitating in the night-side atmosphere. An aurora was also detected on Mars, on 14 August 2004, by the SPICAM instrument aboard Mars Express. The aurora was located at Terra Cimmeria, in the region of 177° East, 52° South. The total size of the emission region was about 30 km across, and possibly about 8 km high. By analyzing a map of crustal magnetic anomalies compiled with data from Mars Global Surveyor, scientists observed that the region of the emissions corresponded to an area where the strongest magnetic field is localized. This correlation indicates that the origin of the light emission was a flux of electrons moving along the crust magnetic lines and exciting the upper atmosphere of Mars.[55][56]