A Bussard ramjet, one of many possible methods that could serve as propulsion of a starship.

Interstellar travel is the term used for hypothetical crewed or uncrewed travel between stars or planetary systems. Interstellar travel will be much more difficult than interplanetary spaceflight; the distances between the planets in the Solar System are less than 30 astronomical units (AU)—whereas the distances between stars are typically hundreds of thousands of AU, and usually expressed in light-years. Because of the vastness of those distances, interstellar travel would require a high percentage of the speed of light; huge travel time, lasting from decades to millennia or longer; or a combination of both.

The speeds required for interstellar travel in a human lifetime far exceed what current methods of spacecraft propulsion can provide. Even with a hypothetically perfectly efficient propulsion system, the kinetic energy corresponding to those speeds is enormous by today's standards of energy production. Moreover, collisions by the spacecraft with cosmic dust and gas can produce very dangerous effects both to passengers and the spacecraft itself.

A number of strategies have been proposed to deal with these problems, ranging from giant arks that would carry entire societies and ecosystems, to microscopic space probes. Many different spacecraft propulsion systems have been proposed to give spacecraft the required speeds, including nuclear propulsion, beam-powered propulsion, and methods based on speculative physics.[1]

For both crewed and uncrewed interstellar travel, considerable technological and economic challenges need to be met. Even the most optimistic views about interstellar travel see it as only being feasible decades from now—the more common view is that it is a century or more away. However, in spite of the challenges, when interstellar travel will be realized, a wide range of scientific benefits is expected.[2]

Most interstellar travel concepts require a developed space logistics system capable of moving millions of tons to a construction / operating location, and most would require gigawatt-scale power for construction or power (such as Star Wisp or Light Sail type concepts). Such a system could grow organically if space-based solar power became a significant component of Earth's energy mix. Consumer demand for a multi-terawatt system would automatically create the necessary multi-million ton/year logistical system.[3]

Challenges

Interstellar distances

Distances between the planets in the Solar System are often measured in astronomical units (AU), defined as the average distance between the Sun and Earth, some 1.5×108 kilometers (93 million miles). Venus, the closest other planet to Earth is (at closest approach) 0.28 AU away. Neptune, the farthest planet from the Sun, is 29.8 AU away. As of January 2018, Voyager 1, the farthest man-made object from Earth, is 141.5 AU away.[4]The closest known star, Proxima Centauri, is approximately 268,332 AU away, or over 9,000 times farther away than Neptune.

| Object | A.U. | light time |

|---|---|---|

| Moon | 0.0026 | 1.3 seconds |

| Sun | 1 | 8 minutes |

| Venus (nearest planet) | 0.28 | 2.41 minutes |

| Neptune (farthest planet) | 29.8 | 4.1 hours |

| Voyager 1 | 141.5 | 19.61 hours |

| Proxima Centauri | 268,332 | 4.24 years |

Because of this, distances between stars are usually expressed in light-years, defined as the distance that a light photon travels in a year. Light in a vacuum travels around 300,000 kilometres (186,000 mi) per second, so this is some 9.461×1012 kilometers (5.879 trillion miles) or 1 light-year (63,241 AU) in a year. Proxima Centauri is 4.243 light-years away.

Another way of understanding the vastness of interstellar distances is by scaling: One of the closest stars to the Sun, Alpha Centauri A (a Sun-like star), can be pictured by scaling down the Earth–Sun distance to one meter (3.28 ft). On this scale, the distance to Alpha Centauri A would be 276 kilometers (171 miles).

The fastest outward-bound spacecraft yet sent, Voyager 1, has covered 1/600 of a light-year in 30 years and is currently moving at 1/18,000 the speed of light. At this rate, a journey to Proxima Centauri would take 80,000 years.[5]

Required energy

A significant factor contributing to the difficulty is the energy that must be supplied to obtain a reasonable travel time. A lower bound for the required energy is the kinetic energy where

where  is the final mass. If deceleration

on arrival is desired and cannot be achieved by any means other than

the engines of the ship, then the lower bound for the required energy is

doubled to

is the final mass. If deceleration

on arrival is desired and cannot be achieved by any means other than

the engines of the ship, then the lower bound for the required energy is

doubled to  .[6]

.[6]

The velocity for a manned round trip of a few decades to even the nearest star is several thousand times greater than those of present space vehicles. This means that due to the

term in the kinetic energy formula, millions of times as much energy is

required. Accelerating one ton to one-tenth of the speed of light

requires at least 450 petajoules or 4.50×1017 joules or 125 terawatt-hours[7] (world energy consumption 2008 was 143,851 terawatt-hours),[citation needed]

without factoring in efficiency of the propulsion mechanism. This

energy has to be generated onboard from stored fuel, harvested from the

interstellar medium, or projected over immense distances.

term in the kinetic energy formula, millions of times as much energy is

required. Accelerating one ton to one-tenth of the speed of light

requires at least 450 petajoules or 4.50×1017 joules or 125 terawatt-hours[7] (world energy consumption 2008 was 143,851 terawatt-hours),[citation needed]

without factoring in efficiency of the propulsion mechanism. This

energy has to be generated onboard from stored fuel, harvested from the

interstellar medium, or projected over immense distances.

Interstellar medium

A knowledge of the properties of the interstellar gas and dust through which the vehicle must pass is essential for the design of any interstellar space mission.[8] A major issue with traveling at extremely high speeds is that interstellar dust may cause considerable damage to the craft, due to the high relative speeds and large kinetic energies involved. Various shielding methods to mitigate this problem have been proposed.[9] Larger objects (such as macroscopic dust grains) are far less common, but would be much more destructive. The risks of impacting such objects, and methods of mitigating these risks, have been discussed in the literature, but many unknowns remain[10] and, owing to the inhomogeneous distribution of interstellar matter around the Sun, will depend on direction travelled.[8] Although a high density interstellar medium may cause difficulties for many interstellar travel concepts, interstellar ramjets, and some proposed concepts for decelerating interstellar spacecraft, would actually benefit from a denser interstellar medium.[8]Hazards

The crew of an interstellar ship would face several significant hazards, including the psychological effects of long-term isolation, the effects of exposure to ionizing radiation, and the physiological effects of weightlessness to the muscles, joints, bones, immune system, and eyes. There also exists the risk of impact by micrometeoroids and other space debris. These risks represent challenges that have yet to be overcome.[11]Wait calculation

It has been argued that an interstellar mission that cannot be completed within 50 years should not be started at all. Instead, assuming that a civilization is still on an increasing curve of propulsion system velocity and not yet having reached the limit, the resources should be invested in designing a better propulsion system. This is because a slow spacecraft would probably be passed by another mission sent later with more advanced propulsion (the incessant obsolescence postulate).[12] On the other hand, Andrew Kennedy has shown that if one calculates the journey time to a given destination as the rate of travel speed derived from growth (even exponential growth) increases, there is a clear minimum in the total time to that destination from now.[13] Voyages undertaken before the minimum will be overtaken by those that leave at the minimum, whereas voyages that leave after the minimum will never overtake those that left at the minimum.Prime targets for interstellar travel

There are 59 known stellar systems within 40 light years of the Sun, containing 81 visible stars. The following could be considered prime targets for interstellar missions:[12]| System | Distance (ly) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha Centauri | 4.3 | Closest system. Three stars (G2, K1, M5). Component A is similar to the Sun (a G2 star). On August 24, 2016, the discovery of an Earth-size exoplanet (Proxima Centauri b) orbiting in the habitable zone of Proxima Centauri was announced. |

| Barnard's Star | 6 | Small, low-luminosity M5 red dwarf. Second closest to Solar System. |

| Sirius | 8.7 | Large, very bright A1 star with a white dwarf companion. |

| Epsilon Eridani | 10.8 | Single K2 star slightly smaller and colder than the Sun. It has two asteroid belts, might have a giant and one much smaller planet,[14] and may possess a Solar-System-type planetary system. |

| Tau Ceti | 11.8 | Single G8 star similar to the Sun. High probability of possessing a Solar-System-type planetary system: current evidence shows 5 planets with potentially two in the habitable zone. |

| Wolf 1061 | ~14 | Wolf 1061 c is 4.3 times the size of Earth; it may have rocky terrain. It also sits within the ‘Goldilocks’ zone where it might be possible for liquid water to exist.[15] |

| Gliese 581 planetary system | 20.3 | Multiple planet system. The unconfirmed exoplanet Gliese 581g and the confirmed exoplanet Gliese 581d are in the star's habitable zone. |

| Gliese 667C | 22 | A system with at least six planets. A record-breaking three of these planets are super-Earths lying in the zone around the star where liquid water could exist, making them possible candidates for the presence of life.[16] |

| Vega | 25 | A very young system possibly in the process of planetary formation.[17] |

| TRAPPIST-1 | 39 | A recently discovered system which boasts 7 Earth-like planets, some of which may have liquid water. The discovery is a major advancement in finding a habitable planet and in finding a planet that could support life. |

Existing and near-term astronomical technology is capable of finding planetary systems around these objects, increasing their potential for exploration

Proposed methods

Slow, uncrewed probes

Slow interstellar missions based on current and near-future propulsion technologies are associated with trip times starting from about one hundred years to thousands of years. These missions consist of sending a robotic probe to a nearby star for exploration, similar to interplanetary probes such as used in the Voyager program.[18] By taking along no crew, the cost and complexity of the mission is significantly reduced although technology lifetime is still a significant issue next to obtaining a reasonable speed of travel. Proposed concepts include Project Daedalus, Project Icarus, Project Dragonfly, Project Longshot,[19] and more recently Breakthrough Starshot.Nanoprobes

Near-lightspeed nano spacecraft might be possible within the near future built on existing microchip technology with a newly developed nanoscale thruster. Researchers at the University of Michigan are developing thrusters that use nanoparticles as propellant. Their technology is called "nanoparticle field extraction thruster", or nanoFET. These devices act like small particle accelerators shooting conductive nanoparticles out into space.[21]Michio Kaku, a theoretical physicist, has suggested that clouds of "smart dust" be sent to the stars, which may become possible with advances in nanotechnology. Kaku also notes that a large number of nanoprobes would need to be sent due to the vulnerability of very small probes to be easily deflected by magnetic fields, micrometeorites and other dangers to ensure the chances that at least one nanoprobe will survive the journey and reach the destination.[22]

Given the light weight of these probes, it would take much less energy to accelerate them. With onboard solar cells, they could continually accelerate using solar power. One can envision a day when a fleet of millions or even billions of these particles swarm to distant stars at nearly the speed of light and relay signals back to Earth through a vast interstellar communication network.

As a near-term solution, small, laser-propelled interstellar probes, based on current CubeSat technology were proposed in the context of Project Dragonfly.[19]

Slow, manned missions

In crewed missions, the duration of a slow interstellar journey presents a major obstacle and existing concepts deal with this problem in different ways.[23] They can be distinguished by the "state" in which humans are transported on-board of the spacecraft.Generation ships

A generation ship (or world ship) is a type of interstellar ark in which the crew that arrives at the destination is descended from those who started the journey. Generation ships are not currently feasible because of the difficulty of constructing a ship of the enormous required scale and the great biological and sociological problems that life aboard such a ship raises.Suspended animation

Scientists and writers have postulated various techniques for suspended animation. These include human hibernation and cryonic preservation. Although neither is currently practical, they offer the possibility of sleeper ships in which the passengers lie inert for the long duration of the voyage.[28]Frozen embryos

A robotic interstellar mission carrying some number of frozen early stage human embryos is another theoretical possibility. This method of space colonization requires, among other things, the development of an artificial uterus, the prior detection of a habitable terrestrial planet, and advances in the field of fully autonomous mobile robots and educational robots that would replace human parents.[29]Island hopping through interstellar space

Interstellar space is not completely empty; it contains trillions of icy bodies ranging from small asteroids (Oort cloud) to possible rogue planets. There may be ways to take advantage of these resources for a good part of an interstellar trip, slowly hopping from body to body or setting up waystations along the way.[30]Fast missions

If a spaceship could average 10 percent of light speed (and decelerate at the destination, for manned missions), this would be enough to reach Proxima Centauri in forty years. Several propulsion concepts have been proposed [31] that might be eventually developed to accomplish this (see also the section below on propulsion methods), but none of them are ready for near-term (few decades) developments at acceptable cost.Time dilation

Assuming faster-than-light travel is impossible, one might conclude that a human can never make a round-trip farther from Earth than 20 light years if the traveler is active between the ages of 20 and 60. A traveler would never be able to reach more than the very few star systems that exist within the limit of 20 light years from Earth. This, however, fails to take into account relativistic time dilation.[32] Clocks aboard an interstellar ship would run slower than Earth clocks, so if a ship's engines were capable of continuously generating around 1 g of acceleration (which is comfortable for humans), the ship could reach almost anywhere in the galaxy and return to Earth within 40 years ship-time (see diagram). Upon return, there would be a difference between the time elapsed on the astronaut's ship and the time elapsed on Earth.For example, a spaceship could travel to a star 32 light-years away, initially accelerating at a constant 1.03g (i.e. 10.1 m/s2) for 1.32 years (ship time), then stopping its engines and coasting for the next 17.3 years (ship time) at a constant speed, then decelerating again for 1.32 ship-years, and coming to a stop at the destination. After a short visit, the astronaut could return to Earth the same way. After the full round-trip, the clocks on board the ship show that 40 years have passed, but according to those on Earth, the ship comes back 76 years after launch.

From the viewpoint of the astronaut, onboard clocks seem to be running normally. The star ahead seems to be approaching at a speed of 0.87 light years per ship-year. The universe would appear contracted along the direction of travel to half the size it had when the ship was at rest; the distance between that star and the Sun would seem to be 16 light years as measured by the astronaut.

At higher speeds, the time on board will run even slower, so the astronaut could travel to the center of the Milky Way (30,000 light years from Earth) and back in 40 years ship-time. But the speed according to Earth clocks will always be less than 1 light year per Earth year, so, when back home, the astronaut will find that more than 60 thousand years will have passed on Earth.

Constant acceleration

Regardless of how it is achieved, a propulsion system that could produce acceleration continuously from departure to arrival would be the fastest method of travel. A constant acceleration journey is one where the propulsion system accelerates the ship at a constant rate for the first half of the journey, and then decelerates for the second half, so that it arrives at the destination stationary relative to where it began. If this were performed with an acceleration similar to that experienced at the Earth's surface, it would have the added advantage of producing artificial "gravity" for the crew. Supplying the energy required, however, would be prohibitively expensive with current technology.[34]

From the perspective of a planetary observer, the ship will appear to accelerate steadily at first, but then more gradually as it approaches the speed of light (which it cannot exceed). It will undergo hyperbolic motion.[35] The ship will be close to the speed of light after about a year of accelerating and remain at that speed until it brakes for the end of the journey.

From the perspective of an onboard observer, the crew will feel a gravitational field opposite the engine's acceleration, and the universe ahead will appear to fall in that field, undergoing hyperbolic motion. As part of this, distances between objects in the direction of the ship's motion will gradually contract until the ship begins to decelerate, at which time an onboard observer's experience of the gravitational field will be reversed.

When the ship reaches its destination, if it were to exchange a message with its origin planet, it would find that less time had elapsed on board than had elapsed for the planetary observer, due to time dilation and length contraction.

The result is an impressively fast journey for the crew.

Propulsion

Rocket concepts

All rocket concepts are limited by the rocket equation, which sets the characteristic velocity available as a function of exhaust velocity and mass ratio, the ratio of initial (M0, including fuel) to final (M1, fuel depleted) mass.Very high specific power, the ratio of thrust to total vehicle mass, is required to reach interstellar targets within sub-century time-frames.[36] Some heat transfer is inevitable and a tremendous heating load must be adequately handled.

Thus, for interstellar rocket concepts of all technologies, a key engineering problem (seldom explicitly discussed) is limiting the heat transfer from the exhaust stream back into the vehicle.[37]

Ion engine

A type of electric propulsion, spacecraft such as Dawn use an ion engine. In an ion engine, electric power is used to create charged particles of the propellant, usually the gas xenon, and accelerate them to extremely high velocities. The exhaust velocity of conventional rockets is limited by the chemical energy stored in the fuel’s molecular bonds, which limits the thrust to about 5 km/s. This gives them high power[clarification needed] (for lift-off from Earth, for example) but limits the top speed. By contrast, ion engines have low force, but the top speed in principle is limited only by the electrical power available on the spacecraft and on the gas ions being accelerated. The exhaust speed of the charged particles range from 15 km/s to 35 km/s.[38]Nuclear fission powered

Fission-electric

Nuclear-electric or plasma engines, operating for long periods at low thrust and powered by fission reactors, have the potential to reach speeds much greater than chemically powered vehicles or nuclear-thermal rockets. Such vehicles probably have the potential to power Solar System exploration with reasonable trip times within the current century. Because of their low-thrust propulsion, they would be limited to off-planet, deep-space operation. Electrically powered spacecraft propulsion powered by a portable power-source, say a nuclear reactor, producing only small accelerations, would take centuries to reach for example 15% of the velocity of light, thus unsuitable for interstellar flight during a single human lifetime.[39]Fission-fragment

Fission-fragment rockets use nuclear fission to create high-speed jets of fission fragments, which are ejected at speeds of up to 12,000 km/s (7,500 mi/s). With fission, the energy output is approximately 0.1% of the total mass-energy of the reactor fuel and limits the effective exhaust velocity to about 5% of the velocity of light. For maximum velocity, the reaction mass should optimally consist of fission products, the "ash" of the primary energy source, so no extra reaction mass need be bookkept in the mass ratio.Nuclear pulse

Modern Pulsed Fission Propulsion Concept.

Based on work in the late 1950s to the early 1960s, it has been technically possible to build spaceships with nuclear pulse propulsion engines, i.e. driven by a series of nuclear explosions. This propulsion system contains the prospect of very high specific impulse (space travel's equivalent of fuel economy) and high specific power.[40]

Project Orion team member Freeman Dyson proposed in 1968 an interstellar spacecraft using nuclear pulse propulsion that used pure deuterium fusion detonations with a very high fuel-burnup fraction. He computed an exhaust velocity of 15,000 km/s and a 100,000-tonne space vehicle able to achieve a 20,000 km/s delta-v allowing a flight-time to Alpha Centauri of 130 years.[41] Later studies indicate that the top cruise velocity that can theoretically be achieved by a Teller-Ulam thermonuclear unit powered Orion starship, assuming no fuel is saved for slowing back down, is about 8% to 10% of the speed of light (0.08-0.1c).[42] An atomic (fission) Orion can achieve perhaps 3%-5% of the speed of light. A nuclear pulse drive starship powered by fusion-antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion units would be similarly in the 10% range and pure matter-antimatter annihilation rockets would be theoretically capable of obtaining a velocity between 50% to 80% of the speed of light. In each case saving fuel for slowing down halves the maximum speed. The concept of using a magnetic sail to decelerate the spacecraft as it approaches its destination has been discussed as an alternative to using propellant, this would allow the ship to travel near the maximum theoretical velocity.[43] Alternative designs utilizing similar principles include Project Longshot, Project Daedalus, and Mini-Mag Orion. The principle of external nuclear pulse propulsion to maximize survivable power has remained common among serious concepts for interstellar flight without external power beaming and for very high-performance interplanetary flight.

In the 1970s the Nuclear Pulse Propulsion concept further was refined by Project Daedalus by use of externally triggered inertial confinement fusion, in this case producing fusion explosions via compressing fusion fuel pellets with high-powered electron beams. Since then, lasers, ion beams, neutral particle beams and hyper-kinetic projectiles have been suggested to produce nuclear pulses for propulsion purposes.[44]

A current impediment to the development of any nuclear-explosion-powered spacecraft is the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which includes a prohibition on the detonation of any nuclear devices (even non-weapon based) in outer space. This treaty would, therefore, need to be renegotiated, although a project on the scale of an interstellar mission using currently foreseeable technology would probably require international cooperation on at least the scale of the International Space Station.

Nuclear fusion rockets

Fusion rocket starships, powered by nuclear fusion reactions, should conceivably be able to reach speeds of the order of 10% of that of light, based on energy considerations alone. In theory, a large number of stages could push a vehicle arbitrarily close to the speed of light. These would burn such light element fuels as deuterium, tritium, 3He, 11B, and 7Li. Because fusion yields about 0.3–0.9% of the mass of the nuclear fuel as released energy, it is energetically more favorable than fission, which releases <0 .1="" 0="" 4="" a="" achievable="" although="" and="" are="" as="" available="" be="" best="" c.="" centuries.="" concepts="" correspondingly="" decades="" difficulties="" easily="" energetically="" energy="" engineering="" exhaust="" fission="" for="" fraction="" fuel="" fusion="" high-energy="" higher="" however="" human="" intractable="" involve="" large="" lifetime="" long="" loss.="" mass-energy.="" massive="" maximum="" may="" most="" nbsp="" nearest-term="" nearest="" neutrons="" of="" offer="" or="" out="" p="" potentially="" prospects="" reactions="" release="" s="" seem="" significant="" source="" stars="" still="" technological="" than="" the="" their="" these="" they="" thus="" to="" travel="" turn="" typically="" velocities="" which="" within=""><0 .1="" 4="" a="" achievable="" although="" and="" are="" as="" available="" be="" best="" c.="" centuries.="" concepts="" correspondingly="" decades="" difficulties="" easily="" energetically="" energy="" engineering="" exhaust="" fission="" for="" fraction="" fuel="" fusion="" high-energy="" higher="" however="" human="" intractable="" involve="" large="" lifetime="" long="" loss.="" mass-energy.="" massive="" maximum="" may="" most="" nbsp="" nearest-term="" nearest="" neutrons="" of="" offer="" or="" out="" p="" potentially="" prospects="" reactions="" release="" s="" seem="" significant="" source="" stars="" still="" technological="" than="" the="" their="" these="" they="" thus="" to="" travel="" turn="" typically="" velocities="" which="" within="">

Daedalus interstellar vehicle.

Early studies include Project Daedalus, performed by the British Interplanetary Society in 1973–1978, and Project Longshot, a student project sponsored by NASA and the US Naval Academy, completed in 1988. Another fairly detailed vehicle system, "Discovery II", designed and optimized for crewed Solar System exploration, based on the D3He reaction but using hydrogen as reaction mass, has been described by a team from NASA's Glenn Research Center. It achieves characteristic velocities greater than 300 km/s with an acceleration of ~1.7•10−3 g, with a ship initial mass of ~1700 metric tons, and payload fraction above 10%. Although these are still far short of the requirements for interstellar travel on human timescales, the study seems to represent a reasonable benchmark towards what may be approachable within several decades, which is not impossibly beyond the current state-of-the-art. Based on the concept's 2.2% burnup fraction it could achieve a pure fusion product exhaust velocity of ~3,000 km/s.

Antimatter rockets

Speculating that production and storage of antimatter should become feasible, two further issues need to be considered. First, in the annihilation of antimatter, much of the energy is lost as high-energy gamma radiation, and especially also as neutrinos, so that only about 40% of mc2 would actually be available if the antimatter were simply allowed to annihilate into radiations thermally.[31] Even so, the energy available for propulsion would be substantially higher than the ~1% of mc2 yield of nuclear fusion, the next-best rival candidate.

Second, heat transfer from the exhaust to the vehicle seems likely to transfer enormous wasted energy into the ship (e.g. for 0.1g ship acceleration, approaching 0.3 trillion watts per ton of ship mass), considering the large fraction of the energy that goes into penetrating gamma rays. Even assuming shielding was provided to protect the payload (and passengers on a crewed vehicle), some of the energy would inevitably heat the vehicle, and may thereby prove a limiting factor if useful accelerations are to be achieved.

More recently, Friedwardt Winterberg proposed that a matter-antimatter GeV gamma ray laser photon rocket is possible by a relativistic proton-antiproton pinch discharge, where the recoil from the laser beam is transmitted by the Mössbauer effect to the spacecraft.[49]

Rockets with an external energy source

Rockets deriving their power from external sources, such as a laser, could replace their internal energy source with an energy collector, potentially reducing the mass of the ship greatly and allowing much higher travel speeds. Geoffrey A. Landis has proposed for an interstellar probe, with energy supplied by an external laser from a base station powering an Ion thruster.[50]Non-rocket concepts

A problem with all traditional rocket propulsion methods is that the spacecraft would need to carry its fuel with it, thus making it very massive, in accordance with the rocket equation. Several concepts attempt to escape from this problem:[31][51]Interstellar ramjets

In 1960, Robert W. Bussard proposed the Bussard ramjet, a fusion rocket in which a huge scoop would collect the diffuse hydrogen in interstellar space, "burn" it on the fly using a proton–proton chain reaction, and expel it out of the back. Later calculations with more accurate estimates suggest that the thrust generated would be less than the drag caused by any conceivable scoop design. Yet the idea is attractive because the fuel would be collected en route (commensurate with the concept of energy harvesting), so the craft could theoretically accelerate to near the speed of light. The limitation is due to the fact that the reaction can only accelerate the propellant to 0.12c. Thus the drag of catching interstellar dust and the thrust of accelerating that same dust to 0.12c would be the same when the speed is 0.12c, preventing further acceleration.Beamed propulsion

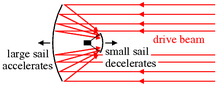

This diagram illustrates Robert L. Forward's scheme for slowing down an interstellar light-sail at the star system destination.

A light sail or magnetic sail powered by a massive laser or particle accelerator in the home star system could potentially reach even greater speeds than rocket- or pulse propulsion methods, because it would not need to carry its own reaction mass and therefore would only need to accelerate the craft's payload. Robert L. Forward proposed a means for decelerating an interstellar light sail in the destination star system without requiring a laser array to be present in that system. In this scheme, a smaller secondary sail is deployed to the rear of the spacecraft, whereas the large primary sail is detached from the craft to keep moving forward on its own. Light is reflected from the large primary sail to the secondary sail, which is used to decelerate the secondary sail and the spacecraft payload.[52] In 2002, Geoffrey A. Landis of NASA's Glen Research center also proposed a laser-powered, propulsion, sail ship that would host a diamond sail (of a few nanometers thick) powered with the use of solar energy.[53] With this proposal, this interstellar ship would, theoretically, be able to reach 10 percent the speed of light.

A magnetic sail could also decelerate at its destination without depending on carried fuel or a driving beam in the destination system, by interacting with the plasma found in the solar wind of the destination star and the interstellar medium.[54][55]

The following table lists some example concepts using beamed laser propulsion as proposed by the physicist Robert L. Forward:[56]

| Mission | Laser Power | Vehicle Mass | Acceleration | Sail Diameter | Maximum Velocity (% of c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Flyby – Alpha Centauri, 40 years | |||||

| outbound stage | 65 GW | 1 t | 0.036 g | 3.6 km | 11% @ 0.17 ly |

| 2. Rendezvous – Alpha Centauri, 41 years | |||||

| outbound stage | 7,200 GW | 785 t | 0.005 g | 100 km | 21% @ 4.29 ly |

| deceleration stage | 26,000 GW | 71 t | 0.2 g | 30 km | 21% @ 4.29 ly |

| 3. Manned – Epsilon Eridani, 51 years (including 5 years exploring star system) | |||||

| outbound stage | 75,000,000 GW | 78,500 t | 0.3 g | 1000 km | 50% @ 0.4 ly |

| deceleration stage | 21,500,000 GW | 7,850 t | 0.3 g | 320 km | 50% @ 10.4 ly |

| return stage | 710,000 GW | 785 t | 0.3 g | 100 km | 50% @ 10.4 ly |

| deceleration stage | 60,000 GW | 785 t | 0.3 g | 100 km | 50% @ 0.4 ly |

Interstellar travel catalog to use photogravitational assists for a full stop

The following table is based on work by Heller, Hippke and Kervella.| Name | Travel time (yr) |

Distance (ly) |

Luminosity (L☉) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sirius A | 68.90 | 8.58 | 24.20 |

| α Centauri A | 101.25 | 4.36 | 1.52 |

| α Centauri B | 147.58 | 4.36 | 0.50 |

| Procyon A | 154.06 | 11.44 | 6.94 |

| Vega | 167.39 | 25.02 | 50.05 |

| Altair | 176.67 | 16.69 | 10.70 |

| Fomalhaut A | 221.33 | 25.13 | 16.67 |

| Denebola | 325.56 | 35.78 | 14.66 |

| Castor A | 341.35 | 50.98 | 49.85 |

| Epsilon Eridiani | 363.35 | 10.50 | 0.50 |

- Successive assists at α Cen A and B could allow travel times to 75 yr to both stars.

- Lightsail has a nominal mass-to-surface ratio (σnom) of 8.6×10−4 gram m−2 for a nominal graphene-class sail.

- Area of the Lightsail, about 105 m2 = (316 m)2

- Velocity up to 37,300 km s−1 (12.5% c)

Pre-accelerated fuel

Achieving start-stop interstellar trip times of less than a human lifetime require mass-ratios of between 1,000 and 1,000,000, even for the nearer stars. This could be achieved by multi-staged vehicles on a vast scale.[45] Alternatively large linear accelerators could propel fuel to fission propelled space-vehicles, avoiding the limitations of the Rocket equation.Theoretical concepts

Faster-than-light travel

Artist's depiction of a hypothetical Wormhole Induction Propelled Spacecraft, based loosely on the 1994 "warp drive" paper of Miguel Alcubierre. Credit: NASA CD-98-76634 by Les Bossinas.

Scientists and authors have postulated a number of ways by which it might be possible to surpass the speed of light, but even the most serious-minded of these are highly speculative.[59]

It is also debatable whether faster-than-light travel is physically possible, in part because of causality concerns: travel faster than light may, under certain conditions, permit travel backwards in time within the context of special relativity.[60] Proposed mechanisms for faster-than-light travel within the theory of general relativity require the existence of exotic matter[59] and it is not known if this could be produced in sufficient quantity.

Alcubierre drive

In physics, the Alcubierre drive is based on an argument, within the framework of general relativity and without the introduction of wormholes, that it is possible to modify a spacetime in a way that allows a spaceship to travel with an arbitrarily large speed by a local expansion of spacetime behind the spaceship and an opposite contraction in front of it.[61] Nevertheless, this concept would require the spaceship to incorporate a region of exotic matter, or hypothetical concept of negative mass.[61]Artificial black hole

A theoretical idea for enabling interstellar travel is by propelling a starship by creating an artificial black hole and using a parabolic reflector to reflect its Hawking radiation. Although beyond current technological capabilities, a black hole starship offers some advantages compared to other possible methods. Getting the black hole to act as a power source and engine also requires a way to convert the Hawking radiation into energy and thrust. One potential method involves placing the hole at the focal point of a parabolic reflector attached to the ship, creating forward thrust. A slightly easier, but less efficient method would involve simply absorbing all the gamma radiation heading towards the fore of the ship to push it onwards, and let the rest shoot out the back.Wormholes

Wormholes are conjectural distortions in spacetime that theorists postulate could connect two arbitrary points in the universe, across an Einstein–Rosen Bridge. It is not known whether wormholes are possible in practice. Although there are solutions to the Einstein equation of general relativity that allow for wormholes, all of the currently known solutions involve some assumption, for example the existence of negative mass, which may be unphysical.[65] However, Cramer et al. argue that such wormholes might have been created in the early universe, stabilized by cosmic string.[66] The general theory of wormholes is discussed by Visser in the book Lorentzian Wormholes.[67]Designs and studies

Enzmann starship

The Enzmann starship, as detailed by G. Harry Stine in the October 1973 issue of Analog, was a design for a future starship, based on the ideas of Robert Duncan-Enzmann. The spacecraft itself as proposed used a 12,000,000 ton ball of frozen deuterium to power 12–24 thermonuclear pulse propulsion units. Twice as long as the Empire State Building and assembled in-orbit, the spacecraft was part of a larger project preceded by interstellar probes and telescopic observation of target star systems.[68]Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion, one of the projects of Icarus Interstellar.[69]NASA research

NASA has been researching interstellar travel since its formation, translating important foreign language papers and conducting early studies on applying fusion propulsion, in the 1960s, and laser propulsion, in the 1970s, to interstellar travel.The NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program (terminated in FY 2003 after a 6-year, $1.2-million study, because "No breakthroughs appear imminent.")[70] identified some breakthroughs that are needed for interstellar travel to be possible.[71]

Geoffrey A. Landis of NASA's Glenn Research Center states that a laser-powered interstellar sail ship could possibly be launched within 50 years, using new methods of space travel. "I think that ultimately we're going to do it, it's just a question of when and who," Landis said in an interview. Rockets are too slow to send humans on interstellar missions. Instead, he envisions interstellar craft with extensive sails, propelled by laser light to about one-tenth the speed of light. It would take such a ship about 43 years to reach Alpha Centauri if it passed through the system. Slowing down to stop at Alpha Centauri could increase the trip to 100 years,[72] whereas a journey without slowing down raises the issue of making sufficiently accurate and useful observations and measurements during a fly-by.

100 Year Starship study

The 100 Year Starship (100YSS) is the name of the overall effort that will, over the next century, work toward achieving interstellar travel. The effort will also go by the moniker 100YSS. The 100 Year Starship study is the name of a one-year project to assess the attributes of and lay the groundwork for an organization that can carry forward the 100 Year Starship vision.Harold ("Sonny") White[73] from NASA's Johnson Space Center is a member of Icarus Interstellar,[74] the nonprofit foundation whose mission is to realize interstellar flight before the year 2100. At the 2012 meeting of 100YSS, he reported using a laser to try to warp spacetime by 1 part in 10 million with the aim of helping to make interstellar travel possible.[75]

Other designs

- Project Orion, manned interstellar ship (1958–1968).

- Project Daedalus, unmanned interstellar probe (1973–1978).

- Starwisp, unmanned interstellar probe (1985).[76]

- Project Longshot, unmanned interstellar probe (1987–1988).

- Starseed/launcher, fleet of unmanned interstellar probes (1996)

- Project Valkyrie, manned interstellar ship (2009)

- Project Icarus, unmanned interstellar probe (2009–2014).

- Sun-diver, unmanned interstellar probe[77]

- Breakthrough Starshot, fleet of unmanned interstellar probes, announced in April 12, 2016.

Non-profit organizations

A few organisations dedicated to interstellar propulsion research and advocacy for the case exist worldwide. These are still in their infancy, but are already backed up by a membership of a wide variety of scientists, students and professionals.- 100 Year Starship [81]

- Icarus Interstellar [74]

- Tau Zero Foundation (USA) [82]

- Initiative for Interstellar Studies (UK) [83]

- Fourth Millennium Foundation (Belgium) [84]

- Space Development Cooperative (Canada) [85]

Feasibility

The energy requirements make interstellar travel very difficult. It has been reported that at the 2008 Joint Propulsion Conference, multiple experts opined that it was improbable that humans would ever explore beyond the Solar System.[86] Brice N. Cassenti, an associate professor with the Department of Engineering and Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, stated that at least 100 times the total energy output of the entire world [in a given year] would be required to send a probe to the nearest star.[86]Astrophysicist Sten Odenwald stated that the basic problem is that through intensive studies of thousands of detected exoplanets, most of the closest destinations within 50 light years do not yield Earth-like planets in the star's habitable zones.[87] Given the multi-trillion-dollar expense of some of the proposed technologies, travelers will have to spend up to 200 years traveling at 20% the speed of light to reach the best known destinations. Moreover, once the travelers arrive at their destination (by any means), they will not be able to travel down to the surface of the target world and set up a colony unless the atmosphere is non-lethal. The prospect of making such a journey, only to spend the rest of the colony's life inside a sealed habitat and venturing outside in a spacesuit, may eliminate many prospective targets from the list.

Moving at a speed close to the speed of light and encountering even a tiny stationary object like a grain of sand will have fatal consequences. For example, a gram of matter moving at 90% of the speed of light contains a kinetic energy corresponding to a small nuclear bomb (around 30kt TNT).

Interstellar missions not for human benefit

Explorative high-speed missions to Alpha Centauri, as planned for by the Breakthrough Starshot initiative, are projected to be realizable within the 21st century.[88] It is alternatively possible to plan for unmanned slow-cruising missions taking millennia to arrive. These probes would not be for human benefit in the sense that one can not foresee whether there would be anybody around on earth interested in then back-transmitted science data. An example would be the Genesis mission,[89] which aims to bring unicellular life, in the spirit of directed panspermia, to habitable but otherwise barren planets.[90] Comparatively slow cruising Genesis probes, with a typical speed of , corresponding to about

, corresponding to about  , can be decelerated using a magnetic sail. Unmanned missions not for human benefit would hence be feasible [91]

, can be decelerated using a magnetic sail. Unmanned missions not for human benefit would hence be feasible [91]