The city of Machu Picchu was constructed c. 1450 AD, at the height of the Inca Empire.

It has commanding views down two valleys and a nearly impassable

mountain at its back. There is an ample supply of spring water and

enough land for a plentiful food supply. The hillsides leading to it

have been terraced to provide farmland for crops, reduce soil erosion, protect against landslides, and create steep slopes to discourage potential invaders.

Environmental history is the study of human interaction with

the natural world over time, emphasising the active role nature plays in

influencing human affairs and vice versa.

Environmental history emerged in the United States out of the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and much of its impetus still stems from present-day global environmental concerns.

The field was founded on conservation issues but has broadened in scope

to include more general social and scientific history and may deal with

cities, population or sustainable development.

As all history occurs in the natural world, environmental history tends

to focus on particular time-scales, geographic regions, or key themes.

It is also a strongly multidisciplinary subject that draws widely on

both the humanities and natural science.

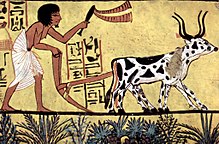

The subject matter of environmental history can be divided into three main components. The first, nature itself and its change over time, includes the physical impact of humans on the Earth's land, water, atmosphere and biosphere. The second category, how humans use nature, includes the environmental consequences of increasing population, more effective technology and changing patterns of production and consumption. Other key themes are the transition from nomadic hunter-gatherer communities to settled agriculture in the neolithic revolution, the effects of colonial expansion and settlements, and the environmental and human consequences of the industrial and technological revolutions. Finally, environmental historians study how people think about nature - the way attitudes, beliefs and values influence interaction with nature, especially in the form of myths, religion and science.

Origin of name and early works

In 1967 Roderick Nash published "Wilderness and the American Mind", a work that has become a classic text of early environmental history. In an address to the Organization of American Historians in 1969 (published in 1970) Nash used the expression "environmental history", although 1972 is generally taken as the date when the term was first coined. The 1959 book by Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920,

while being a major contribution to American political history, is now

also regarded as a founding document in the field of environmental

history. Hays is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Pittsburgh.

Historiography

Brief overviews of the historiography of environmental history have been given by J. R. McNeill, Richard White, and J. Donald Hughes. In 2014 Oxford University Press published a volume of 25 essays called The Oxford Handbook of Environmental History.

Definition

There

is no universally accepted definition of environmental history. In

general terms it is a history that tries to explain why our environment

is like it is and how humanity has influenced its current condition, as

well as commenting on the problems and opportunities of tomorrow. Donald Worster's

widely quoted 1988 definition states that environmental history is the

"interaction between human cultures and the environment in the past".

In 2001, J. Donald Hughes defined the subject as the “study of

human relationships through time with the natural communities of which

they are a part in order to explain the processes of change that affect

that relationship”.

and, in 2006, as "history that seeks understanding of human beings as

they have lived, worked and thought in relationship to the rest of

nature through the changes brought by time".

"As a method, environmental history is the use of ecological analysis

as a means of understanding human history...an account of changes in

human societies as they relate to changes in the natural environment”.

Environmental historians are also interested in "what people think

about nature, and how they have expressed those ideas in folk religions,

popular culture, literature and art”. In 2003, J. R. McNeill defined it as "the history of the mutual relations between humankind and the rest of nature".

Subject matter

Traditional historical analysis

has over time extended its range of study from the activities and

influence of a few significant people to a much broader social,

political, economic, and cultural analysis. Environmental history

further broadens the subject matter of conventional history. In 1988,

Donald Worster stated that environmental history “attempts to make

history more inclusive in its narratives” by examining the “role and place of nature in human life”,

and in 1993, that “Environmental history explores the ways in which the

biophysical world has influenced the course of human history and the

ways in which people have thought about and tried to transform their

surroundings”. The interdependency of human and environmental factors in the creation of landscapes is expressed through the notion of the cultural landscape. Worster also questioned the scope of the discipline, asking: "We study humans and nature; therefore can anything human or natural be outside our enquiry?"

Environmental history is generally treated as a subfield of history.

But some environmental historians challenge this assumption, arguing

that while traditional history is human history – the story of people

and their institutions, "humans cannot place themselves outside the principles of nature".

In this sense, they argue that environmental history is a version of

human history within a larger context, one less dependent on anthropocentrism (even though anthropogenic change is at the center of its narrative).

Dimensions

General view of Funkville in 1864, Oil Creek, Pennsylvania, USA

J. Donald Hughes responded to the view that environmental history is "light on theory"

or lacking theoretical structure by viewing the subject through the

lens of three "dimensions": nature and culture, history and science, and

scale.

This advances beyond Worster's recognition of three broad clusters of

issues to be addressed by environmental historians although both

historians recognize that the emphasis of their categories might vary

according to the particular study as, clearly, some studies will concentrate more on society and human affairs and others more on the environment.

Themes

Several

themes are used to express these historical dimensions. A more

traditional historical approach is to analyse the transformation of the

globe’s ecology through themes like the separation of man from nature

during the neolithic revolution, imperialism and colonial expansion, exploration, agricultural change, the effects of the industrial and technological revolution, and urban expansion. More environmental topics include human impact through influences on forestry, fire, climate change, sustainability and so on. According to Paul Warde, “the

increasingly sophisticated history of colonization and migration can

take on an environmental aspect, tracing the pathways of ideas and

species around the globe and indeed is bringing about an increased use

of such analogies and ‘colonial’ understandings of processes within

European history.” The importance of the colonial enterprise in Africa, the Caribbean and Indian Ocean has been detailed by Richard Grove.

Much of the literature consists of case-studies targeted at the global, national and local levels.

Scale

Although

environmental history can cover billions of years of history over the

whole Earth, it can equally concern itself with local scales and brief

time periods. Many environmental historians are occupied with local, regional and national histories. Some historians link their subject exclusively to the span of human history – "every time period in human history" while others include the period before human presence on Earth as a legitimate part of the discipline. Ian Simmons's Environmental History of Great Britain

covers a period of about 10,000 years. There is a tendency to

difference in time scales between natural and social phenomena: the

causes of environmental change that stretch back in time may be dealt

with socially over a comparatively brief period.

Although at all times environmental influences have extended

beyond particular geographic regions and cultures, during the 20th and

early 21st centuries anthropogenic environmental change has assumed

global proportions, most prominently with climate change but also as a

result of settlement, the spread of disease and the globalization of

world trade.

History

Nature preservationist John Muir with U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (left) on Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park

The questions of environmental history date back to antiquity, including Hippocrates,

the father of medicine, who asserted that different cultures and human

temperaments could be related to the surroundings in which peoples lived

in Airs, Waters, Places. Scholars as varied as Ibn Khaldun and Montesquieu found climate to be a key determinant of human behavior. During the Enlightenment,

there was a rising awareness of the environment and scientists

addressed themes of sustainability via natural history and medicine. However, the origins of the subject in its present form are generally traced to the 20th century.

In 1929 a group of French historians founded the journal Annales,

in many ways a forerunner of modern environmental history since it took

as its subject matter the reciprocal global influences of the

environment and human society. The idea of the impact of the physical

environment on civilizations was espoused by this Annales School to describe the long term developments that shape human history by focusing away from political and intellectual history, toward agriculture, demography, and geography. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie,

a pupil of the Annales School, was the first to really embrace, in the

1950s, environmental history in a more contemporary form. One of the most influential members of the Annales School was Lucien Febvre (1878–1956), whose book A Geographical Introduction to History is now a classic in the field.

The most influential empirical and theoretical work in the

subject has been done in the United States where teaching programs first

emerged and a generation of trained environmental historians is now

active.

In the United States environmental history as an independent field of

study emerged in the general cultural reassessment and reform of the

1960s and 1970s along with environmentalism, "conservation history",

and a gathering awareness of the global scale of some environmental

issues. This was in large part a reaction to the way nature was

represented in history at the time, which “portrayed the advance of

culture and technology as releasing humans from dependence on the

natural world and providing them with the means to manage it [and]

celebrated human mastery over other forms of life and the natural

environment, and expected technological improvement and economic growth

to accelerate”. Environmental historians intended to develop a post-colonial historiography that was "more inclusive in its narratives".

Moral and political inspiration

Moral and political inspiration to environmental historians has come from American writers and activists such as Henry Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Rachel Carson.

Environmental history "frequently promoted a moral and political agenda

although it steadily became a more scholarly enterprise". Early attempts to define the field were made in the United States by Roderick Nash in “The State of Environmental History” and in other works by frontier historians Frederick Jackson Turner, James Malin, and Walter Prescott Webb,

who analyzed the process of settlement. Their work was expanded by a

second generation of more specialized environmental historians such as Alfred Crosby, Samuel P. Hays, Donald Worster, William Cronon, Richard White, Carolyn Merchant, J. R. McNeill, Donald Hughes, and Chad Montrie in the United States and Paul Warde, Sverker Sorlin, Robert A. Lambert, T.C. Smout, and Peter Coates in Europe.

British Empire

Although environmental history was growing rapidly after 1970, it only reached historians of the British Empire in the 1990s.

Gregory Barton argues that the concept of environmentalism emerged from

forestry studies, and emphasizes the British imperial role in that

research. He argues that imperial forestry movement in India around

1900 included government reservations, new methods of fire protection,

and attention to revenue-producing forest management. The result eased

the fight between romantic preservationists and laissez-faire

businessmen, thus giving the compromise from which modern

environmentalism emerged.

In recent years numerous scholars cited by James Beattie have examined the environmental impact of the Empire.

Beinart and Hughes argue that the discovery and commercial or

scientific use of new plants was an important concern in the 18th and

19th centuries. The efficient use of rivers through dams and irrigation

projects was an expensive but important method of raising agricultural

productivity. Searching for more efficient ways of using natural

resources, the British moved flora, fauna and commodities around the

world, sometimes resulting in ecological disruption and radical

environmental change. Imperialism also stimulated more modern attitudes

toward nature and subsidized botany and agricultural research.

Scholars have used the British Empire to examine the utility of the

new concept of eco-cultural networks as a lens for examining

interconnected, wide-ranging social and environmental processes.

Current practice

Frontier historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1861–1932)

In the United States the American Society for Environmental History

was founded in 1975 while the first institute devoted specifically to

environmental history in Europe was established in 1991, based at the

University of St. Andrews in Scotland. In 1986, the Dutch foundation for

the history of environment and hygiene Net Werk was founded and publishes four newsletters per year. In the UK the White Horse Press in Cambridge has, since 1995, published the journal Environment and History

which aims to bring scholars in the humanities and biological sciences

closer together in constructing long and well-founded perspectives on

present day environmental problems and a similar publication Tijdschrift voor Ecologische Geschiedenis (Journal for Environmental History)

is a combined Flemish-Dutch initiative mainly dealing with topics in

the Netherlands and Belgium although it also has an interest in European

environmental history. Each issue contains abstracts in English, French

and German. In 1999 the Journal was converted into a yearbook for

environmental history. In Canada the Network in Canadian History and Environment

facilitates the growth of environmental history through numerous

workshops and a significant digital infrastructure including their

website and podcast.

Communication between European nations is restricted by language

difficulties. In April 1999 a meeting was held in Germany to overcome

these problems and to co-ordinate environmental history in Europe. This

meeting resulted in the creation of the European Society for Environmental History

in 1999. Only two years after its establishment, ESEH held its first

international conference in St. Andrews, Scotland. Around 120 scholars

attended the meeting and 105 papers were presented on topics covering

the whole spectrum of environmental history. The conference showed that

environmental history is a viable and lively field in Europe and since

then ESEH has expanded to over 400 members and continues to grow and

attracted international conferences in 2003 and 2005. In 1999 the Centre for Environmental History

was established at the University of Stirling. Some history departments

at European universities are now offering introductory courses in

environmental history and postgraduate courses in Environmental history

have been established at the Universities of Nottingham, Stirling and

Dundee and more recently a Graduierten Kolleg was created at the University of Göttingen in Germany. In 2009, the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society

(RCC), an international, interdisciplinary center for research and

education in the environmental humanities and social sciences, was

founded as a joint initiative of Munich's Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and the Deutsches Museum, with the generous support of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

The Environment & Society Portal (environmentandsociety.org) is the

Rachel Carson Center's open access digital archive and publication

platform.

Related disciplines

Environmental history prides itself in bridging the gap between the

arts and natural sciences although to date the scales weigh on the side

of science. A definitive list of related subjects would be lengthy

indeed and singling out those for special mention a difficult task.

However, those frequently quoted include, historical geography, the history and philosophy of science, history of technology and climate science. On the biological side there is, above all, ecology and historical ecology, but also forestry and especially forest history, archaeology and anthropology. When the subject engages in environmental advocacy it has much in common with environmentalism.

With increasing globalization and the impact of global trade on

resource distribution, concern over never-ending economic growth and the

many human inequities environmental history is now gaining allies in

the fields of ecological and environmental economics.

Engagement with sociological thinkers and the humanities is

limited but cannot be ignored through the beliefs and ideas that guide

human action. This has been seen as the reason for a perceived lack of

support from traditional historians.

Issues

The

subject has a number of areas of lively debate. These include discussion

concerning: what subject matter is most appropriate; whether

environmental advocacy can detract from scholarly objectivity; standards

of professionalism in a subject where much outstanding work has been

done by non-historians; the relative contribution of nature and humans

in determining the passage of history; the degree of connection with,

and acceptance by, other disciplines - but especially mainstream

history. For Paul Warde the sheer scale, scope and diffuseness of the

environmental history endeavour calls for an analytical toolkit "a range

of common issues and questions to push forward collectively" and a

"core problem". He sees a lack of "human agency" in its texts and

suggest it be written more to act: as a source of information for

environmental scientists; incorporation of the notion of risk; a closer

analysis of what it is we mean by "environment"; confronting the way

environmental history is at odds with the humanities because it

emphasises the division between "materialist, and cultural or

constructivist explanations for human behaviour".

Global sustainability

Achieving sustainability will enable the Earth to continue supporting human life as we know it. Blue Marble NASA composite images: 2001 (left), 2002 (right)

Many of the themes of environmental history inevitably examine the

circumstances that produced the environmental problems of the present

day, a litany of themes that challenge global sustainability including: population, consumerism and materialism, climate change, waste disposal, deforestation and loss of wilderness, industrial agriculture, species extinction, depletion of natural resources, invasive organisms and urban development. The simple message of sustainable use of renewable resources is frequently repeated and early as 1864 George Perkins Marsh

was pointing out that the changes we make in the environment may later

reduce the environments usefulness to humans so any changes should be

made with great care - what we would nowadays call enlightened self-interest. Richard Grove has pointed out that "States will act to prevent environmental degradation only when their economic interests are threatened".

Advocacy

It is not clear whether environmental history should promote a moral

or political agenda. The strong emotions raised by environmentalism,

conservation and sustainability can interfere with historical

objectivity: polemical tracts and strong advocacy can compromise

objectivity and professionalism. Engagement with the political process

certainly has its academic perils

although accuracy and commitment to the historical method is not

necessarily threatened by environmental involvement: environmental

historians have a reasonable expectation that their work will inform

policy-makers.

A recent historiographical shift has placed an increased emphasis

on inequality as an element of environmental history. Imbalances of

power in resources, industry, and politics have resulted in the burden

of industrial pollution being shifted to less powerful populations in

both the geographic and social spheres.

An critical examination of the traditional environmentalist movement

from this historical perspective notes the ways in which early advocates

of environmentalism sought the aesthetic preservation of middle-class

spaces and sheltered their own communities from the worst effects of air

and water pollution, while neglecting the plight of the less

privileged.

Communities with less economic and sociopolitical power often

lack the resources to get involved in environmental advocacy.

Environmental history increasingly highlights the ways in which the

middle-class environmental movement has fallen short and left behind

entire communities. Interdisciplinary research now understands historic

inequality as a lens through which to predict future social developments

in the environmental sphere, particularly with regard to climate change. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

cautions that a warming planet will exacerbate environmental and other

inequalities, particularly with regard to: "(a) increase in the exposure

of the disadvantaged groups to the adverse effects of climate change;

(b) increase in their susceptibility to damage caused by climate change;

and (c) decrease in their ability to cope and recover from the damage

suffered."

As an interdisciplinary field that encompasses a new understanding of

social justice dynamics in a rapidly changing global climate,

environmental history is inherently advocative.

Declensionist narratives

Narratives of environmental history tend to be declensionist, that is, accounts of progressive decline under human activity.

Presentism and culpability

Under the accusation of "presentism" it is sometimes claimed that,

with its genesis in the late 20th century environmentalism and

conservation issues, environmental history is simply a reaction to

contemporary problems, an "attempt to read late twentieth century

developments and concerns back into past historical periods in which

they were not operative, and certainly not conscious to human

participants during those times".

This is strongly related to the idea of culpability. In environmental

debate blame can always be apportioned, but it is more constructive for

the future to understand the values and imperatives of the period under

discussion so that causes are determined and the context explained.

Environmental determinism

For some environmental historians "the general conditions of the

environment, the scale and arrangement of land and sea, the availability

of resources, and the presence or absence of animals available for

domestication, and associated organisms and disease vectors, that makes

the development of human cultures possible and even predispose the

direction of their development" and that "history is inevitably guided by forces that are not of human origin or subject to human choice". This approach has been attributed to American environmental historians Webb and Turner and, more recently to Jared Diamond in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel,

where the presence or absence of disease vectors and resources such as

plants and animals that are amenable to domestication that may not only

stimulate the development of human culture but even determine, to some

extent, the direction of that development. The claim that the path of

history has been forged by environmental rather than cultural forces is

referred to as environmental determinism while, at the other extreme, is what may be called cultural determinism.

An example of cultural determinism would be the view that human

influence is so pervasive that the idea of pristine nature has little

validity - that there is no way of relating to nature without culture.

Methodology

Recording historical events

Useful guidance on the process of doing environmental history has been given by Donald Worster, Carolyn Merchant, William Cronon and Ian Simmons.

Worster's three core subject areas (the environment itself, human

impacts on the environment, and human thought about the environment) are

generally taken as a starting point for the student as they encompass

many of the different skills required. The tools are those of both

history and science with a requirement for fluency in the language of

natural science and especially ecology.

In fact methodologies and insights from a range of physical and social

sciences is required, there seeming to be universal agreement that

environmental history is indeed a multidisciplinary subject.

Future

Old and new human uses of the atmosphere

Environmental history, like all historical studies, shares the hope

that through an examination of past events it may be possible to forge a

more considered future. In particular a greater depth of historical

knowledge can inform environmental controversies and guide policy

decisions.

The subject continues to provide new perspectives, offering

cooperation between scholars with different disciplinary backgrounds and

providing an improved historical context to resource and environmental

problems. There seems little doubt that, with increasing concern for our

environmental future, environmental history will continue along the

path of environmental advocacy from which it originated as “human impact on the living systems of the planet bring us no closer to utopia, but instead to a crisis of survival”

with key themes being population growth, climate change, conflict over

environmental policy at different levels of human organization,

extinction, biological invasions, the environmental consequences of

technology especially biotechnology, the reduced supply of resources -

most notably energy, materials and water. Hughes comments that

environmental historians “will find themselves increasingly

challenged by the need to explain the background of the world market

economy and its effects on the global environment. Supranational

instrumentalities threaten to overpower conservation in a drive for what

is called sustainable development, but which in fact envisions no

limits to economic growth”. Hughes also notes that "environmental history is notably absent from nations that most adamantly reject US, or Western influences".

Michael Bess sees the world increasingly permeated by potent

technologies in a process he calls “artificialization” which has been

accelerating since the 1700s, but at a greatly accelerated rate after

1945. Over the next fifty years, this transformative process stands a

good chance of turning our physical world, and our society, upside-down.

Environmental historians can “play a vital role in helping humankind

to understand the gale-force of artifice that we have unleashed on our

planet and on ourselves”.

Against this background “environmental history can give an

essential perspective, offering knowledge of the historical process that

led to the present situation, give examples of past problems and

solutions, and an analysis of the historical forces that must be dealt

with” or, as expressed by William Cronon, "The

viability and success of new human modes of existing within the

constraints of the environment and its resources requires both an

understanding of the past and an articulation of a new ethic for the

future."