| |

| Function | Crewed orbital launch and reentry |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | United Space Alliance Thiokol/Alliant Techsystems (SRBs) Lockheed Martin/Martin Marietta (ET) Boeing/Rockwell (orbiter) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Project cost | US$ 210 billion (2010) |

| Cost per launch | US$ 450 million (2011) to 1.5 billion (2011) |

| Size | |

| Height | 56.1 m (184.2 ft) |

| Diameter | 8.7 m (28.5 ft) |

| Mass | 2,030 t (4,470,000 lb) |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | 27,500 kg (60,600 lb) |

| Payload to ISS | 16,050 kg (35,380 lb) |

| Payload to GTO | 3,810 kg (8,400 lb) |

| Payload to Polar orbit | 12,700 kg (28,000 lb) |

| Payload to Earth return | 14,400 kg (31,700 lb) |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Retired |

| Launch sites | LC-39, Kennedy Space Center SLC-6, Vandenberg AFB (unused) |

| Total launches | 135 |

| Successes | 134 launches and 133 landings |

| Failures | 2 Challenger (launch failure, 7 fatalities), Columbia (re-entry failure, 7 fatalities) |

| First flight | April 12, 1981 |

| Last flight | July 21, 2011 |

| Notable payloads | Tracking and Data Relay Satellites Spacelab Hubble Space Telescope Galileo, Magellan, Ulysses Compton Gamma Ray Observatory Mir Docking Module Chandra X-ray Observatory ISS components |

| Boosters - Solid Rocket Boosters | |

| No. boosters | 2 |

| Engines | 2 solid |

| Thrust | 12,500 kN (2,800,000 lbf) each, sea level liftoff |

| Specific impulse | 269 seconds (2.64 km/s) |

| Burn time | 124 s |

| Fuel | Solid (Ammonium perchlorate composite propellant) |

| First stage - Orbiter plus External Tank | |

| Engines | 3 SSMEs located on Orbiter |

| Thrust | 5,250 kN (1,180,000 lbf) total, sea level liftoff |

| Specific impulse | 455 seconds (4.46 km/s) |

| Burn time | 480 s |

| Fuel | LOX/LH2 |

The Space Shuttle was a partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program name was Space Transportation System (STS), taken from a 1969 plan for a system of reusable spacecraft of which it was the only item funded for development. The first of four orbital test flights occurred in 1981, leading to operational flights beginning in 1982. In addition to the prototype whose completion was cancelled, five complete Shuttle systems were built and used on a total of 135 missions from 1981 to 2011, launched from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Operational missions launched numerous satellites, interplanetary probes, and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST); conducted science experiments in orbit; and participated in construction and servicing of the International Space Station. The Shuttle fleet's total mission time was 1322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds.

Shuttle components included the Orbiter Vehicle (OV) with three clustered Rocketdyne RS-25 main engines, a pair of recoverable solid rocket boosters (SRBs), and the expendable external tank (ET) containing liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. The Space Shuttle was launched vertically, like a conventional rocket, with the two SRBs operating in parallel with the OV's three main engines, which were fueled from the ET. The SRBs were jettisoned before the vehicle reached orbit, and the ET was jettisoned just before orbit insertion, which used the orbiter's two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines. At the conclusion of the mission, the orbiter fired its OMS to de-orbit and re-enter the atmosphere. The orbiter then glided as a spaceplane to a runway landing, usually to the Shuttle Landing Facility at Kennedy Space Center, Florida or Rogers Dry Lake in Edwards Air Force Base, California. After landing at Edwards, the orbiter was flown back to the KSC on the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a specially modified Boeing 747.

The first orbiter, Enterprise, was built in 1976, used in Approach and Landing Tests and had no orbital capability. Four fully operational orbiters were initially built: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of these, two were lost in mission accidents: Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003, with a total of fourteen astronauts killed. A fifth operational (and sixth in total) orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger. The Space Shuttle was retired from service upon the conclusion of Atlantis's final flight on July 21, 2011. The U.S. has since relied primarily on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft to transport astronauts to the International Space Station.

Overview

The Space Shuttle was a partially reusable human spaceflight vehicle capable of reaching low Earth orbit, commissioned and operated by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration

(NASA) from 1981 to 2011. It resulted from shuttle design studies

conducted by NASA and the U.S. Air Force in the 1960s and was first

proposed for development as part of an ambitious second-generation Space Transportation System (STS) of space vehicles to follow the Apollo program in a September 1969 report of a Space Task Group headed by Vice President Spiro Agnew to President Richard Nixon.

Nixon's post-Apollo NASA budgeting withdrew support of all system

components except the Shuttle, to which NASA applied the STS name.

The vehicle consisted of a spaceplane for orbit and re-entry, fueled from an expendable External Tank containing liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, with two reusable strap-on solid rocket boosters. The first of four orbital test flights occurred in 1981, leading to operational flights beginning in 1982, all launched from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida. The system was retired from service in 2011 after 135 missions, with Atlantis making the final launch of the three-decade Shuttle program on July 8, 2011. The program ended after Atlantis

landed at the Kennedy Space Center on July 21, 2011. Major missions

included launching numerous satellites and interplanetary probes, conducting space science experiments, and servicing and construction of space stations. The first orbiter vehicle, named Enterprise, was used in the initial Approach and Landing Tests phase but installation of engines, heat shielding, and other equipment necessary for orbital flight was cancelled. A total of five operational orbiters were built, and of these, two were destroyed in accidents.

It was used for orbital space missions by NASA, the U.S. Department of Defense, the European Space Agency, Japan, and Germany. The United States funded Shuttle development and operations except for the Spacelab modules used on D1 and D2—sponsored by Germany. SL-J was partially funded by Japan.

STS-129 ready for launch

Shuttle approach and landing test crews, 1976

Early concept for a space shuttle refueling a space tug, 1970

At launch, it consisted of the "stack", including the dark orange external tank (ET) (for the first two launches the tank was painted white); two white, slender solid rocket boosters (SRBs); and the Orbiter Vehicle, which contained the crew

and payload. Some payloads were launched into higher orbits with either

of two different upper stages developed for the STS (single-stage Payload Assist Module or two-stage Inertial Upper Stage). The Space Shuttle was stacked in the Vehicle Assembly Building, and the stack mounted on a mobile launch platform held down by four frangible nuts on each SRB, which were detonated at launch.

The Shuttle stack launched vertically like a conventional rocket. It lifted off under the power of its two SRBs and three main engines,

which were fueled by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen from the ET. The

Space Shuttle had a two-stage ascent. The SRBs provided additional

thrust during liftoff and first-stage flight. About two minutes after

liftoff, frangible nuts were fired, releasing the SRBs, which then

parachuted into the ocean, to be retrieved by NASA recovery ships

for refurbishment and reuse. The orbiter and ET continued to ascend on

an increasingly horizontal flight path under power from its main

engines. Upon reaching 17,500 mph (7.8 km/s), necessary for low Earth

orbit, the main engines were shut down. The ET, attached by two

frangible nuts was then jettisoned to burn up in the atmosphere. After jettisoning the external tank, the orbital maneuvering system (OMS) engines were used to adjust the orbit.

The orbiter carried astronauts and payloads such as satellites or space station parts into low Earth orbit, the Earth's upper atmosphere or thermosphere.

Usually, five to seven crew members rode in the orbiter. Two crew

members, the commander and pilot, were sufficient for a minimal flight,

as in the first four "test" flights, STS-1 through STS-4. The typical

payload capacity was about 50,045 pounds (22,700 kg) but could be

increased depending on the choice of launch configuration. The orbiter

carried its payload in a large cargo bay with doors that opened along

the length of its top, a feature which made the Space Shuttle unique

among spacecraft. This feature made possible the deployment of large

satellites such as the Hubble Space Telescope and also the capture and return of large payloads back to Earth.

When the orbiter's space mission was complete, it fired its OMS

thrusters to drop out of orbit and re-enter the lower atmosphere. During descent, the orbiter passed through different layers of the atmosphere and decelerated from hypersonic speed primarily by aerobraking. In the lower atmosphere and landing phase, it was more like a glider but with reaction control system (RCS) thrusters and fly-by-wire-controlled

hydraulically actuated flight surfaces controlling its descent. It

landed on a long runway as a conventional aircraft. The aerodynamic

shape was a compromise between the demands of radically different speeds

and air pressures during re-entry, hypersonic flight, and subsonic

atmospheric flight. As a result, the orbiter had a relatively high sink rate

at low altitudes, and it transitioned during re-entry from using RCS

thrusters at very high altitudes to flight surfaces in the lower

atmosphere.

Early history

President Nixon (right) with NASA Administrator Fletcher in January 1972, three months before Congress approved funding for the Shuttle program

Vision for a Spacelab mission with various equipment in the Shuttle bay

Vision for Space Station Freedom, with an STS orbiter docked

The formal design of what became the Space Shuttle began with the

"Phase A" contract design studies issued in the late 1960s.

Conceptualization had begun two decades earlier, before the Apollo program of the 1960s. One of the places the concept of a spacecraft returning from space to a horizontal landing originated was within NACA, in 1954, in the form of an aeronautics research experiment later named the X-15. The NACA proposal was submitted by Walter Dornberger.

In 1958, the X-15 concept further developed into a proposal to launch an X-15 into space, and another X-series spaceplane proposal, named X-20 Dyna-Soar, as well as variety of aerospace plane concepts and studies. Neil Armstrong

was selected to pilot both the X-15 and the X-20. Though the X-20 was

not built, another spaceplane similar to the X-20 was built several

years later and delivered to NASA in January 1966 called the HL-10 ("HL" indicated "horizontal landing").

In the mid-1960s, the U.S. Air Force conducted classified studies

on next-generation space transportation systems and concluded that

semi-reusable designs were the cheapest choice. It proposed a

development program with an immediate start on a "Class I" vehicle with

expendable boosters, followed by slower development of a "Class II"

semi-reusable design and possible "Class III" fully reusable design

later. In 1967, George Mueller

held a one-day symposium at NASA headquarters to study the options.

Eighty people attended and presented a wide variety of designs,

including earlier U.S. Air Force designs such as the X-20 Dyna-Soar.

In 1968, NASA officially began work on what was then known as the

Integrated Launch and Re-entry Vehicle (ILRV). At the same time, NASA

held a separate Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) competition. NASA

offices in Houston and Huntsville jointly issued a Request for Proposal

(RFP) for ILRV studies to design a spacecraft that could deliver a

payload to orbit but also re-enter the atmosphere and fly back to Earth.

For example, one of the responses was for a two-stage design, featuring

a large booster and a small orbiter, called the DC-3,

one of several Phase A Shuttle designs. After the aforementioned "Phase

A" studies, B, C, and D phases progressively evaluated in-depth designs

up to 1972. In the final design, the bottom stage consisted of

recoverable solid rocket boosters, and the top stage used an expendable

external tank.

In 1969, President Richard Nixon decided to support proceeding

with Space Shuttle development. A series of development programs and

analysis refined the basic design, prior to full development and

testing. In August 1973, the X-24B proved that an unpowered spaceplane could re-enter Earth's atmosphere for a horizontal landing.

Across the Atlantic, European ministers met in Belgium in 1973 to

authorize Western Europe's manned orbital project and its main

contribution to Space Shuttle—the Spacelab program. Spacelab would provide a multidisciplinary orbital space laboratory and additional space equipment for the Shuttle.

Description

STS-1 on the launch pad, December 1980

The Space Shuttle was the first operational orbital spacecraft designed for reuse. It carried different payloads to low Earth orbit, provided crew rotation and supplies for the International Space Station

(ISS), and performed satellite servicing and repair. The orbiter could

also recover satellites and other payloads from orbit and return them to

Earth. Each Shuttle was designed for a projected lifespan of 100

launches or ten years of operational life, although this was later

extended. The person in charge of designing the STS was Maxime Faget, who had also overseen the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo

spacecraft designs. The crucial factor in the size and shape of the

Shuttle orbiter was the requirement that it be able to accommodate the

largest planned commercial and military satellites, and have over 1,000

mile cross-range recovery range to meet the requirement for classified

USAF missions for a once-around abort from a launch to a polar orbit.

The militarily specified 1,085 nmi (2,009 km; 1,249 mi) cross range

requirement was one of the primary reasons for the Shuttle's large

wings, compared to modern commercial designs with very minimal control

surfaces and glide capability. Factors involved in opting for solid

rockets and an expendable fuel tank included the desire of the Pentagon

to obtain a high-capacity payload vehicle for satellite deployment, and

the desire of the Nixon administration to reduce the costs of space exploration by developing a spacecraft with reusable components.

Each Space Shuttle was a reusable launch system composed of three main assemblies: the reusable OV, the expendable ET, and the two reusable SRBs.

Only the OV entered orbit shortly after the tank and boosters are

jettisoned. The vehicle was launched vertically like a conventional

rocket, and the orbiter glided to a horizontal landing like an airplane,

after which it was refurbished for reuse. The SRBs parachuted to

splashdown in the ocean where they were towed back to shore and

refurbished for later Shuttle missions.

Discovery rockets into orbit, seen here just after solid rocket booster (SRB) separation

Tail-end of an orbiter showing various nozzles during an orbital maneuver with ISS

Five operational OVs were built: Columbia (OV-102), Challenger (OV-099), Discovery (OV-103), Atlantis (OV-104), and Endeavour (OV-105). A mock-up, Inspiration, currently stands at the entrance to the Astronaut Hall of Fame. An additional craft, Enterprise

(OV-101), was built for atmospheric testing gliding and landing; it was

originally intended to be outfitted for orbital operations after the

test program, but it was found more economical to upgrade the structural

test article STA-099 into orbiter Challenger (OV-099). An additional test article, dubbed Pathfinder (OV-098), was built for form and fit tests, and is on display at the Alabama Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, AL. Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch in 1986, and Endeavour was built as a replacement from structural spare components. Building Endeavour cost about US$1.7 billion. Columbia broke apart over Texas during re-entry in 2003.

A Space Shuttle launch cost around $450 million. Roger A. Pielke, Jr. has estimated that the Space Shuttle program cost about US$170 billion (2008 dollars) through early 2008; the average cost per flight was about US$1.5 billion. Two missions were paid for by Germany, Spacelab D1 and D2 (D for Deutschland) with a payload control center in Oberpfaffenhofen. D1 was the first time that control of a manned STS mission payload was not in U.S. hands.

At times, the orbiter itself was referred to as the Space Shuttle. This was not technically correct as the Space Shuttle

was the combination of the orbiter, the external tank, and the two

solid rocket boosters. These components, once assembled in the Vehicle Assembly Building originally built to assemble the Apollo Saturn V rocket, were commonly referred to as the "stack".

Responsibility for the Shuttle components was spread among

multiple NASA field centers. The Kennedy Space Center was responsible

for launch, landing and turnaround operations for equatorial orbits (the

only orbit profile actually used in the program), the U.S. Air Force at

the Vandenberg Air Force Base was responsible for launch, landing and turnaround operations for polar orbits (though this was never used), the Johnson Space Center served as the central point for all Shuttle operations, the Marshall Space Flight Center was responsible for the main engines, external tank, and solid rocket boosters, the John C. Stennis Space Center handled main engine testing, and the Goddard Space Flight Center managed the global tracking network.

Orbiter vehicle

Shuttle launch profiles. From left to right: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour.

The orbiter resembled a conventional aircraft, with double-delta wings

swept 81° at the inner leading edge and 45° at the outer leading edge.

Its vertical stabilizer's leading edge was swept back at a 50° angle.

The four elevons, mounted at the trailing edge of the wings, and the rudder/speed

brake, attached at the trailing edge of the stabilizer, with the body

flap, controlled the orbiter during descent and landing.

The orbiter's 60-foot (18 m)-long payload bay, comprising most of the fuselage,

could accommodate cylindrical payloads up to 15 feet (4.6 m) in

diameter. Information declassified in 2011 showed that these

measurements were chosen specifically to accommodate the KH-9 HEXAGON spy satellite operated by the National Reconnaissance Office.

Two mostly-symmetrical lengthwise payload bay doors hinged on either

side of the bay comprised its entire top. Payloads were generally loaded

horizontally into the bay while the orbiter was standing upright on the

launch pad and unloaded vertically in the near-weightless orbital

environment by the orbiter's robotic remote manipulator arm

(under astronaut control), EVA astronauts, or under the payloads' own

power (as for satellites attached to a rocket "upper stage" for

deployment.)

Three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) were mounted on the

orbiter's aft fuselage in a triangular pattern. The engine nozzles could

gimbal

10.5 degrees up and down, and 8.5 degrees from side to side during

ascent to change the direction of their thrust to steer the Shuttle. The

orbiter structure was made primarily from aluminum alloy, although the engine structure was made primarily from titanium alloy.

The operational orbiters built were OV-102 Columbia, OV-099 Challenger, OV-103 Discovery, OV-104 Atlantis, and OV-105 Endeavour.

- Space Shuttle Atlantis transported by a Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), 1998 (NASA)

- An overhead view of Atlantis as it sits atop the Mobile Launcher Platform (MLP) before STS-79. Two Tail Service Masts (TSMs) to either side of the orbiter's tail provide umbilical connections for propellant loading and electrical power.

- Water is released onto the mobile launcher platform on Launch Pad 39A at the start of a sound suppression system test in 2004. During launch, 350,000 US gallons (1,300,000 L) of water are poured onto the pad in 41 seconds.

External tank

An external tank floats away from the orbiter.

Interior of an External Tank

The main function of the Space Shuttle external tank was to supply

the liquid oxygen and hydrogen fuel to the main engines. It was also the

backbone of the launch vehicle, providing attachment points for the two

solid rocket boosters and the orbiter. The external tank was the only

part of the Shuttle system that was not reused. Although the external

tanks were always discarded, it would have been possible to take them

into orbit and re-use them (such as a wet workshop for incorporation into a space station).

Solid rocket boosters

Two solid rocket boosters (SRBs) each provided 12,500 kN (2,800,000 lbf) of thrust at liftoff,

which was 83% of the total thrust at liftoff. The SRBs were jettisoned

two minutes after launch at a height of about 46 km (150,000 ft), and

then deployed parachutes and landed in the ocean to be recovered. The SRB cases were made of steel about ½ inch (13 mm) thick. The solid rocket boosters were re-used many times; the casing used in Ares I engine testing in 2009 consisted of motor cases that had been flown, collectively, on 48 Shuttle missions, including STS-1.

Astronauts who have flown on multiple spacecraft report that Shuttle delivers a rougher ride than Apollo or Soyuz.

The additional vibration is caused by the solid rocket boosters, as

solid fuel does not burn as evenly as liquid fuel. The vibration

dampens down after the solid rocket boosters have been jettisoned.

Orbiter add-ons

The

orbiter could be used in conjunction with a variety of add-ons

depending on the mission. This included orbital laboratories (Spacelab, Spacehab), boosters for launching payloads farther into space (Inertial Upper Stage, Payload Assist Module), and other functions, such as provided by Extended Duration Orbiter, Multi-Purpose Logistics Modules, or Canadarm (RMS). An upper stage called Transfer Orbit Stage (Orbital Science Corp. TOS-21) was also used once with the orbiter.

Other types of systems and racks were part of the modular Spacelab

system —pallets, igloo, IPS, etc., which also supported special missions

such as SRTM.

Spacelab

European astronauts prepare for their Spacelab mission, 1984

Interior of Spacelab LM2

A major component of the Space Shuttle Program was Spacelab,

primarily contributed by a consortium of European countries, and

operated in conjunction with the United States and international

partners.

Supported by a modular system of pressurized modules, pallets, and

systems, Spacelab missions executed on multidisciplinary science,

orbital logistics, and international cooperation. Over 29 missions flew on subjects ranging from astronomy, microgravity, radar, and life sciences, to name a few. Spacelab hardware also supported missions such as Hubble (HST) servicing and space station resupply. STS-2 and STS-3 provided testing, and the first full mission was Spacelab-1 (STS-9) launched on November 28, 1983.

Spacelab formally began in 1973, after a meeting in Brussels, Belgium, by European heads of state.

Within the decade, Spacelab went into orbit and provided Europe and the

United States with an orbital workshop and hardware system. International cooperation, science, and exploration were realized on Spacelab.

Flight systems

The Shuttle was one of the earliest craft to use a computerized fly-by-wire digital flight control system.

This means no mechanical or hydraulic linkages connected the pilot's

control stick to the control surfaces or reaction control system

thrusters. The control algorithm, which used a classical Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) approach, was developed and maintained by Honeywell. The Shuttle's fly-by-wire digital flight control system was composed of 4 control systems each addressing a different mission phase: Ascent, Descent, On-Orbit and Aborts.[citation needed]

Honeywell is also credited with the design and implementation of the

Shuttle's Nose Wheel Steering Control Algorithm that allowed the Orbiter

to safely land at Kennedy Space Center's Shuttle Runway.

A concern with using digital fly-by-wire systems on the Shuttle

was reliability. Considerable research went into the Shuttle computer

system. The Shuttle used five identical redundant IBM 32-bit general

purpose computers (GPCs), model AP-101, constituting a type of embedded system.

Four computers ran specialized software called the Primary Avionics

Software System (PASS). A fifth backup computer ran separate software

called the Backup Flight System (BFS). Collectively they were called the

Data Processing System (DPS).

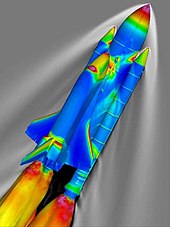

Simulation

of SSLV at Mach 2.46 and 66,000 ft (20,000 m). The surface of the

vehicle is colored by the pressure coefficient, and the gray contours

represent the density of the surrounding air, as calculated using the OVERFLOW software package.

The design goal of the Shuttle's DPS was fail-operational/fail-safe

reliability. After a single failure, the Shuttle could still continue

the mission. After two failures, it could still land safely.

The four general-purpose computers operated essentially in

lockstep, checking each other. If one computer provided a different

result than the other three (i.e. the one computer failed), the three

functioning computers "voted" it out of the system. This isolated it

from vehicle control. If a second computer of the three remaining

failed, the two functioning computers voted it out. A very unlikely

failure mode would have been where two of the computers produced result

A, and two produced result B (a two-two split). In this unlikely case,

one group of two was to be picked at random.

The Backup Flight System (BFS) was separately developed software

running on the fifth computer, used only if the entire four-computer

primary system failed. The BFS was created because although the four

primary computers were hardware redundant, they all ran the same

software, so a generic software problem could crash all of them.

Embedded system avionic

software was developed under totally different conditions from public

commercial software: the number of code lines was tiny compared to a

public commercial software product, changes were only made infrequently

and with extensive testing, and many programming and test personnel

worked on the small amount of computer code. However, in theory it could

have still failed, and the BFS existed for that contingency. While the

BFS could run in parallel with PASS, the BFS never engaged to take over

control from PASS during any Shuttle mission.

The software for the Shuttle computers was written in a high-level language called HAL/S, somewhat similar to PL/I. It is specifically designed for a real time embedded system environment.

The IBM AP-101 computers originally had about 424 kilobytes of magnetic core memory

each. The CPU could process about 400,000 instructions per second. They

had no hard disk drive, and loaded software from magnetic tape

cartridges.

In 1990, the original computers were replaced with an upgraded

model AP-101S, which had about 2.5 times the memory capacity (about 1

megabyte) and three times the processor speed (about 1.2 million

instructions per second). The memory was changed from magnetic core to

semiconductor with battery backup.

Early Shuttle missions, starting in November 1983, took along the Grid Compass,

arguably one of the first laptop computers. The GRiD was given the name

SPOC, for Shuttle Portable Onboard Computer. Use on the Shuttle

required both hardware and software modifications which were

incorporated into later versions of the commercial product. It was used

to monitor and display the Shuttle's ground position, path of the next

two orbits, show where the Shuttle had line of sight communications with

ground stations, and determine points for location-specific

observations of the Earth. The Compass sold poorly, as it cost at least

US$8000, but it offered unmatched performance for its weight and size. NASA was one of its main customers.

During its service life, the Shuttle's Control System never

experienced a failure. Many of the lessons learned have been used to

design today's high speed control algorithms.

Orbiter markings and insignia

Payload specialist Millie Hughes-Fulford, who flew aboard Columbia in 1991, displays the modernist Blackburn & Danne NASA logotype, known as "the worm".

The prototype orbiter Enterprise originally had a flag of the United States

on the upper surface of the left wing and the letters "USA" in black on

the right wing. The name "Enterprise" was painted in black on the

payload bay doors just above the hinge and behind the crew module; on

the aft end of the payload bay doors was the NASA "worm" logotype

in gray. Underneath the rear of the payload bay doors on the side of

the fuselage just above the wing is the text "United States" in black

with a flag of the United States ahead of it.

The first operational orbiter, Columbia, originally had the same markings as Enterprise, although the letters "USA" on the right wing were slightly larger and spaced farther apart. Columbia also had black markings which Enterprise

lacked on its forward RCS module, around the cockpit windows, and on

its vertical stabilizer, and had distinctive black "chines" on the

forward part of its upper wing surfaces, which none of the other

orbiters had.

Challenger established a modified marking scheme for the shuttle fleet that was matched by Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour.

The letters "USA" in black above an American flag were displayed on the

left wing, with the NASA "worm" logotype in gray centered above the

name of the orbiter in black on the right wing. The name of the orbiter

was inscribed not on the payload bay doors, but on the forward fuselage

just below and behind the cockpit windows. This would make the name

visible when the shuttle was photographed in orbit with the doors open.

In 1983, Enterprise had its wing markings changed to match Challenger,

and the NASA "worm" logotype on the aft end of the payload bay doors

was changed from gray to black. Some black markings were added to the

nose, cockpit windows and vertical tail to more closely resemble the

flight vehicles, but the name "Enterprise" remained on the payload bay

doors as there was never any need to open them. Columbia had its name moved to the forward fuselage to match the other flight vehicles after STS-61-C, during the 1986–88 hiatus when the shuttle fleet was grounded following the loss of Challenger, but retained its original wing markings until its last overhaul (after STS-93), and its unique black wing "chines" for the remainder of its operational life.

Beginning in 1998, the flight vehicles' markings were modified to incorporate the NASA "meatball" insignia.

The "worm" logotype, which the agency had phased out, was removed from

the payload bay doors and the "meatball" insignia was added aft of the

"United States" text on the lower aft fuselage. The "meatball" insignia

was also displayed on the left wing, with the American flag above the

orbiter's name, left-justified rather than centered, on the right wing.

The three surviving flight vehicles, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour, still bear these markings as museum displays. Enterprise became the property of the Smithsonian Institution

in 1985 and was no longer under NASA's control when these changes were

made, hence the prototype orbiter still has its 1983 markings and still

has its name on the payload bay doors.

Upgrades

Atlantis was the first Shuttle to fly with a glass cockpit, on STS-101. (composite image)

The Space Shuttle was initially developed in the 1970s,

but received many upgrades and modifications afterward to improve

performance, reliability and safety. Internally, the Shuttle remained

largely similar to the original design, with the exception of the

improved avionics computers. In addition to the computer upgrades, the

original analog primary flight instruments were replaced with modern

full-color, flat-panel display screens, called a glass cockpit,

which is similar to those of contemporary airliners. To facilitate

construction of ISS, the internal airlocks of each orbiter except Columbia

were replaced with external docking systems to allow for a greater

amount of cargo to be stored on the Shuttle's mid-deck during station

resupply missions.

The Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) had several improvements

to enhance reliability and power. This explains phrases such as "Main

engines throttling up to 104 percent." This did not mean the engines

were being run over a safe limit. The 100 percent figure was the

original specified power level. During the lengthy development program, Rocketdyne

determined the engine was capable of safe reliable operation at 104

percent of the originally specified thrust. NASA could have rescaled the

output number, saying in essence 104 percent is now 100 percent. To

clarify this would have required revising much previous documentation

and software, so the 104 percent number was retained. SSME upgrades were

denoted as "block numbers", such as block I, block II, and block IIA.

The upgrades improved engine reliability, maintainability and

performance. The 109% thrust level was finally reached in flight

hardware with the Block II engines in 2001. The normal maximum throttle

was 104 percent, with 106 percent or 109 percent used for mission

aborts.

For the first two missions, STS-1 and STS-2,

the external tank was painted white to protect the insulation that

covers much of the tank, but improvements and testing showed that it was

not required. The weight saved by not painting the tank resulted in an

increase in payload capability to orbit.

Additional weight was saved by removing some of the internal

"stringers" in the hydrogen tank that proved unnecessary. The resulting

"light-weight external tank" was first flown on STS-6 and used on the majority of Shuttle missions. STS-91

saw the first flight of the "super light-weight external tank". This

version of the tank was made of the 2195 aluminum-lithium alloy. It

weighed 3.4 metric tons (7,500 lb) less than the last run of lightweight

tanks, allowing the Shuttle to deliver heavy elements to ISS's high

inclination orbit. As the Shuttle was always operated with a crew, each of these improvements was first flown on operational mission flights.

The solid rocket boosters underwent improvements as well. Design engineers added a third O-ring seal to the joints between the segments after the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

The three nozzles of the Space Shuttle Main Engine with the two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pods, and the vertical stabilizer above.

Several other SRB improvements were planned to improve performance

and safety, but never came to be. These culminated in the considerably

simpler, lower cost, probably safer and better-performing Advanced Solid Rocket Booster.

These rockets entered production in the early to mid-1990s to support

the Space Station, but were later canceled to save money after the

expenditure of $2.2 billion.

The loss of the ASRB program resulted in the development of the Super

LightWeight external Tank (SLWT), which provided some of the increased

payload capability, while not providing any of the safety improvements.

In addition, the U.S. Air Force developed their own much lighter

single-piece SRB design using a filament-wound system, but this too was

canceled.

STS-70 was delayed in 1995, when woodpeckers bored holes in the foam insulation of Discovery's

external tank. Since then, NASA has installed commercial plastic owl

decoys and inflatable owl balloons which had to be removed prior to

launch. The delicate nature of the foam insulation had been the cause of damage to the Thermal Protection System,

the tile heat shield and heat wrap of the orbiter. NASA remained

confident that this damage, while it was the primary cause of the Space

Shuttle Columbia disaster on February 1, 2003, would not

jeopardize the completion of the International Space Station (ISS) in

the projected time allotted.

A cargo-only, unmanned variant of the Shuttle was variously proposed and rejected since the 1980s. It was called the Shuttle-C,

and would have traded re-usability for cargo capability, with large

potential savings from reusing technology developed for the Space

Shuttle. Another proposal was to convert the payload bay into a

passenger area, with versions ranging from 30 to 74 seats, three days in

orbit, and cost US$1.5 million per seat.

On the first four Shuttle missions, astronauts wore modified U.S.

Air Force high-altitude full-pressure suits, which included a

full-pressure helmet during ascent and descent. From the fifth flight, STS-5, until the loss of Challenger, one-piece light blue nomex

flight suits and partial-pressure helmets were worn. A less-bulky,

partial-pressure version of the high-altitude pressure suits with a

helmet was reinstated when Shuttle flights resumed in 1988. The

Launch-Entry Suit ended its service life in late 1995, and was replaced

by the full-pressure Advanced Crew Escape Suit (ACES), which resembled the Gemini space suit in design, but retained the orange color of the Launch-Entry Suit.

To extend the duration that orbiters could stay docked at the ISS, the Station-to-Shuttle Power Transfer System

(SSPTS) was installed. The SSPTS allowed these orbiters to use power

provided by the ISS to preserve their consumables. The SSPTS was first

used successfully on STS-118.

Specifications

Space Shuttle orbiter illustration

Space Shuttle drawing

Space Shuttle wing cutaway

Space Shuttle Orbiter and Soyuz-TM (drawn to scale).

Atlantis and Endeavour

on launch pads. This particular occasion is due to the final Hubble

servicing mission, where the International Space Station is unreachable,

which necessitates having a Shuttle on standby for a possible rescue

mission.

Orbiter (for Endeavour, OV-105)

- Length: 122.17 ft (37.237 m)

- Wingspan: 78.06 ft (23.79 m)

- Height: 56.58 ft (17.25 m)

- Empty weight: 172,000 lb (78,000 kg)

- Gross liftoff weight (Orbiter only): 240,000 lb (110,000 kg)

- Maximum landing weight: 230,000 lb (100,000 kg)

- Payload to Landing (Return Payload): 32,000 lb (14,400 kg)

- Maximum payload: 55,250 lb (25,060 kg)

- Payload to LEO (204 kilometers (110 nmi) @ 28.5° inclination: 27,500 kilograms (60,600 lb)

- Payload to LEO (407 kilometers (220 nmi) @ 51.6° to ISS): 16,050 kilograms (35,380 lb)

- Payload to GTO: 8,390 lb (3,806 kg)

- Payload to Polar Orbit: 28,000 lb (12,700 kg)

- Note launch payloads modified by External Tank (ET) choice (ET, LWT, or SLWT)

- Payload bay dimensions: 15 by 59 ft (4.6 by 18 m) (diameter by length)

- Operational altitude: 100 to 520 nmi (190 to 960 km; 120 to 600 mi)

- Speed: 7,743 m/s (27,870 km/h; 17,320 mph)

- Crossrange: 1,085 nmi (2,009 km; 1,249 mi)

- Main Stage (SSME with external tank)

- Engines: Three Rocketdyne Block II SSMEs, each with a sea level thrust of 393,800 lbf (1,752 kN) at 104% power

- Thrust (at liftoff, sea level, 104% power, all 3 engines): 1,181,400 lbf (5,255 kN)

- Specific impulse: 455 seconds (4.46 km/s)

- Burn time: 480 s

- Fuel: Liquid Hydrogen/Liquid Oxygen

- Orbital Maneuvering System

- Engines: 2 OMS Engines

- Thrust: 53.4 kN (12,000 lbf) combined total vacuum thrust

- Specific impulse: 316 seconds (3.10 km/s)

- Burn time: 150–250 s typical burn; 1250 s deorbit burn

- Fuel: MMH/N2O4

- Crew: Varies.

-

- The earliest Shuttle flights had the minimum crew of two; many later missions a crew of five. By program end, typically seven people would fly: (commander, pilot, several mission specialists, one of whom (MS-2) acted as the flight engineer starting with STS-9 in 1983). On two occasions, eight astronauts have flown (STS-61-A, STS-71). Eleven people could be accommodated in an emergency mission.

External tank (for SLWT)

- Length: 46.9 m (153.8 ft)

- Diameter: 8.4 m (27.6 ft)

- Propellant volume: 2,025 m3 (534,900 U.S. gal)

- Empty weight: 26,535 kg (58,500 lb)

- Gross liftoff weight (for tank): 756,000 kg (1,670,000 lb)

Solid Rocket Boosters

- Length: 45.46 m (149 ft)

- Diameter: 3.71 m (12.2 ft)

- Empty weight (each): 68,000 kg (150,000 lb)

- Gross liftoff weight (each): 571,000 kg (1,260,000 lb)

- Thrust (at liftoff, sea level, each): 12,500 kN (2,800,000 lbf)

- Specific impulse: 269 seconds (2.64 km/s)

- Burn time: 124 s

System Stack

- Height: 56 m (180 ft)

- Gross liftoff weight: 2,000,000 kg (4,400,000 lb)

- Total liftoff thrust: 30,160 kN (6,780,000 lbf)

Mission profile

STS mission profile

Shuttle launch of Atlantis at sunset in 2001. The Sun is behind the camera, and the plume's shadow intersects the Moon across the sky.

Launch preparation

All Space Shuttle missions were launched from Kennedy Space Center (KSC). The weather criteria used for launch included, but were not limited to: precipitation, temperatures, cloud cover, lightning forecast, wind, and humidity. The Shuttle was not launched under conditions where it could have been struck by lightning.

Aircraft are often struck by lightning with no adverse effects because

the electricity of the strike is dissipated through its conductive

structure and the aircraft is not electrically grounded.

Like most jet airliners, the Shuttle was mainly constructed of

conductive aluminum, which would normally shield and protect the

internal systems. However, upon liftoff the Shuttle sent out a long

exhaust plume as it ascended, and this plume could have triggered

lightning by providing a current path to ground. The NASA Anvil Rule for

a Shuttle launch stated that an anvil cloud could not appear within a distance of 10 nautical miles.

The Shuttle Launch Weather Officer monitored conditions until the final

decision to scrub a launch was announced. In addition, the weather

conditions had to be acceptable at one of the Transatlantic Abort

Landing sites (one of several Space Shuttle abort modes) to launch as well as the solid rocket booster recovery area. While the Shuttle might have safely endured a lightning strike, a similar strike caused problems on Apollo 12, so for safety NASA chose not to launch the Shuttle if lightning was possible (NPR8715.5).

Historically, the Shuttle was not launched if its flight would

run from December to January (a year-end rollover or YERO). Its flight

software, designed in the 1970s, was not designed for this, and would

require the orbiter's computers be reset through a change of year, which

could cause a glitch while in orbit. In 2007, NASA engineers devised a

solution so Shuttle flights could cross the year-end boundary.

Launch

After the

final hold in the countdown at T-minus 9 minutes, the Shuttle went

through its final preparations for launch, and the countdown was

automatically controlled by the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS), software

at the Launch Control Center, which stopped the count if it sensed a

critical problem with any of the Shuttle's onboard systems. The GLS

handed off the count to the Shuttle's on-board computers at T minus 31

seconds, in a process called auto sequence start.

At T-minus 16 seconds, the massive sound suppression system (SPS) began to drench the Mobile Launcher Platform (MLP) and SRB trenches with 300,000 US gallons (1,100 m3) of water to protect the Orbiter from damage by acoustical energy and rocket exhaust reflected from the flame trench and MLP during lift off.

At T-minus 10 seconds, hydrogen igniters were activated under

each engine bell to quell the stagnant gas inside the cones before

ignition. Failure to burn these gases could trip the onboard sensors and

create the possibility of an overpressure and explosion of the vehicle

during the firing phase. The main engine turbopumps also began charging

the combustion chambers with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen at this

time. The computers reciprocated this action by allowing the redundant

computer systems to begin the firing phase.

Space Shuttle Main Engine ignition

The three main engines (SSMEs) started at T-6.6 seconds. The

main engines ignited sequentially via the Shuttle's general purpose

computers (GPCs) at 120 millisecond intervals. All three SSMEs were

required to reach 90% rated thrust within three seconds, otherwise the

onboard computers would initiate an RSLS abort. If all three engines indicated nominal performance by T-3

seconds, they were commanded to gimbal to liftoff configuration and the

command would be issued to arm the SRBs for ignition at T-0. Between T-6.6 seconds and T-3

seconds, while the SSMEs were firing but the SRBs were still bolted to

the pad, the offset thrust caused the entire launch stack (boosters,

tank and orbiter) to pitch down 650 mm (25.5 in) measured at the tip of

the external tank. The three second delay after confirmation of SSME

operation was to allow the stack to return to nearly vertical. At T-0 seconds, the 8 frangible nuts holding the SRBs to the pad were detonated, the SSMEs were commanded to 100% throttle, and the SRBs were ignited. By T+0.23 seconds, the SRBs built up enough thrust for liftoff to commence, and reached maximum chamber pressure by T+0.6 seconds. The Johnson Space Center's Mission Control Center assumed control of the flight once the SRBs had cleared the launch tower.

Shortly after liftoff, the Shuttle's main engines were throttled

up to 104.5% and the vehicle began a combined roll, pitch and yaw

maneuver that placed it onto the correct heading (azimuth) for the

planned orbital inclination and in a heads down attitude with wings

level. The Shuttle flew upside down during the ascent phase. This

orientation allowed a trim angle of attack that was favorable for

aerodynamic loads during the region of high dynamic pressure, resulting

in a net positive load factor, as well as providing the flight crew with

a view of the horizon as a visual reference. The vehicle climbed in a

progressively flattening arc, accelerating as the mass of the SRBs and

main tank decreased. To achieve low orbit requires much more horizontal

than vertical acceleration. This was not visually obvious, since the

vehicle rose vertically and was out of sight for most of the horizontal

acceleration. The near circular orbital velocity at the 380 kilometers

(236 mi) altitude of the International Space Station is 27,650 km/h

(17,180 mph), roughly equivalent to Mach 23 at sea level. As the

International Space Station orbits at an inclination of 51.6 degrees,

missions going there must set orbital inclination to the same value in

order to rendezvous with the station.

Around 30 seconds into ascent, the SSMEs were throttled

down—usually to 72%, though this varied—to reduce the maximum

aerodynamic forces acting on the Shuttle at a point called Max Q.

Additionally, the propellant grain design of the SRBs caused their

thrust to drop by about 30% by 50 seconds into ascent. Once the

Orbiter's guidance verified that Max Q would be within Shuttle

structural limits, the main engines were throttled back up to 104.5%;

this throttling down and back up was called the "thrust bucket". To

maximize performance, the throttle level and timing of the thrust bucket

was shaped to bring the Shuttle as close to aerodynamic limits as

possible.

Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) separation during STS-1. The white external tank pictured was used on STS-1 and STS-2.

At around T+126 seconds, pyrotechnic fasteners

released the SRBs and small separation rockets pushed them laterally

away from the vehicle. The SRBs parachuted back to the ocean to be

reused. The Shuttle then began accelerating to orbit on the main

engines. Acceleration at this point would typically fall to .9 g,

and the vehicle would take on a somewhat nose-up angle to the horizon –

it used the main engines to gain and then maintain altitude while it

accelerated horizontally towards orbit. At about five and three-quarter

minutes into ascent, the orbiter's direct communication links with the

ground began to fade, at which point it rolled heads up to reroute its

communication links to the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite system.

At about seven and a half minutes into ascent, the mass of the

vehicle was low enough that the engines had to be throttled back to

limit vehicle acceleration to 3 g (29.4 m/s² or 96.5 ft/s²,

equivalent to accelerating from zero to 105.9 km/h (65.8 mph) in a

second). The Shuttle would maintain this acceleration for the next

minute, and main engine cut-off (MECO) occurred at about eight and a

half minutes after launch.

The main engines were shut down before complete depletion of

propellant, as running dry would have destroyed the engines. The oxygen

supply was terminated before the hydrogen supply, as the SSMEs reacted

unfavorably to other shutdown modes. (Liquid oxygen has a tendency to

react violently, and supports combustion when it encounters hot engine

metal.) A few seconds after MECO, the external tank was released by

firing pyrotechnic fasteners.

At this point the Shuttle and external tank were on a slightly suborbital trajectory, coasting up towards apogee. Once at apogee, about half an hour after MECO, the Shuttle's Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines were fired to raise its perigee

and achieve orbit, while the external tank fell back into the

atmosphere and burned up over the Indian Ocean or the Pacific Ocean

depending on launch profile.

The sealing action of the tank plumbing and lack of pressure relief

systems on the external tank helped it break up in the lower atmosphere.

After the foam burned away during re-entry, the heat caused a pressure

buildup in the remaining liquid oxygen and hydrogen until the tank

exploded. This ensured that any pieces that fell back to Earth were

small.

- Ascent tracking

Contraves-Goerz Kineto Tracking Mount used to image the space Shuttle during launch ascent

The Shuttle was monitored throughout its ascent for short range

tracking (10 seconds before liftoff through 57 seconds after), medium

range (7 seconds before liftoff through 110 seconds after) and long

range (7 seconds before liftoff through 165 seconds after). Short range

cameras included 22 16mm cameras on the Mobile Launch Platform and 8

16mm on the Fixed Service Structure, 4 high speed fixed cameras located

on the perimeter of the launch complex plus an additional 42 fixed

cameras with 16mm motion picture film. Medium range cameras included

remotely operated tracking cameras at the launch complex plus 6 sites

along the immediate coast north and south of the launch pad, each with

800mm lens and high speed cameras running 100 frames per second. These

cameras ran for only 4–10 seconds due to limitations in the amount of

film available. Long range cameras included those mounted on the

external tank, SRBs and orbiter itself which streamed live video back to

the ground providing valuable information about any debris falling

during ascent. Long range tracking cameras with 400-inch film and

200-inch video lenses were operated by a photographer at Playalinda Beach as well as 9 other sites from 38 miles north at the Ponce Inlet to 23 miles south to Patrick Air Force Base

(PAFB) and additional mobile optical tracking camera was stationed on

Merritt Island during launches. A total of 10 HD cameras were used both

for ascent information for engineers and broadcast feeds to networks

such as NASA TV and HDNet. The number of cameras significantly increased and numerous existing cameras were upgraded at the recommendation of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board to provide better information about the debris during launch. Debris was also tracked using a pair of Weibel Continuous Pulse Doppler X-band radars, one on board the SRB recovery ship MV Liberty Star

positioned north east of the launch pad and on a ship positioned south

of the launch pad. Additionally, during the first 2 flights following

the loss of Columbia and her crew, a pair of NASA WB-57

reconnaissance aircraft equipped with HD Video and Infrared flew at

60,000 feet (18,000 m) to provide additional views of the launch ascent.

Kennedy Space Center also invested nearly $3 million in improvements

to the digital video analysis systems in support of debris tracking.

In orbit

Once in orbit, the Shuttle usually flew at an altitude of 320 km (170 nmi), although the STS-82 mission reached 620 km (330 nmi).

In the 1980s and 1990s, many flights involved space science missions on

the NASA/ESA Spacelab, or launching various types of satellites and

science probes. By the 1990s and 2000s the focus shifted more to

servicing the space station, with fewer satellite launches. Most

missions involved staying in orbit several days to two weeks, although

longer missions were possible with the Extended Duration Orbiter add-on or when attached to a space station. STS-80 was the longest at almost 17 days and 16 hours.

Atlantis docked at Harmony module of the International Space Station

Astronaut with satellite

Endeavour docked at ISS

Re-entry and landing

Almost the entire Space Shuttle re-entry procedure, except for

lowering the landing gear and deploying the air data probes, was

normally performed under computer control. However, the re-entry could

be flown entirely manually if an emergency arose. The approach and

landing phase could be controlled by the autopilot, but was usually hand

flown.

Glowing plasma trail from Space Shuttle Atlantis re-entry as seen from the Space Station

The vehicle began re-entry by firing the Orbital maneuvering system

engines, while flying upside down, backside first, in the opposite

direction to orbital motion for approximately three minutes, which

reduced the Shuttle's velocity by about 200 mph (322 km/h). The

resultant slowing of the Shuttle lowered its orbital perigee

down into the upper atmosphere. The Shuttle then flipped over, by

pushing its nose down (which was actually "up" relative to the Earth,

because it was flying upside down). This OMS firing was done roughly

halfway around the globe from the landing site.

The vehicle started encountering more significant air density in the lower thermosphere at about 400,000 ft (120 km), at around Mach 25, 8,200 m/s (30,000 km/h; 18,000 mph). The vehicle was controlled by a combination of RCS thrusters

and control surfaces, to fly at a 40-degree nose-up attitude, producing

high drag, not only to slow it down to landing speed, but also to

reduce reentry heating. As the vehicle encountered progressively denser

air, it began a gradual transition from spacecraft to aircraft. In a

straight line, its 40-degree nose-up attitude would cause the descent

angle to flatten-out, or even rise. The vehicle therefore performed a

series of four steep S-shaped banking turns, each lasting several

minutes, at up to 70 degrees of bank, while still maintaining the

40-degree angle of attack. In this way it dissipated speed sideways

rather than upwards. This occurred during the 'hottest' phase of

re-entry, when the heat-shield glowed red and the G-forces were at their

highest. By the end of the last turn, the transition to aircraft was

almost complete. The vehicle leveled its wings, lowered its nose into a

shallow dive and began its approach to the landing site.

- A Space Shuttle model undergoes a wind tunnel test in 1975. This test is simulating the ionized gasses that surround a Shuttle as it reenters the atmosphere.

The orbiter's maximum glide ratio/lift-to-drag ratio varies considerably with speed, ranging from 1:1 at hypersonic speeds, 2:1 at supersonic speeds and reaching 4.5:1 at subsonic speeds during approach and landing.

In the lower atmosphere, the orbiter flies much like a

conventional glider, except for a much higher descent rate, over 50 m/s

(180 km/h; 110 mph) or 9,800 fpm. At approximately Mach 3, two air data

probes, located on the left and right sides of the orbiter's forward

lower fuselage, are deployed to sense air pressure related to the

vehicle's movement in the atmosphere.

- Final approach and landing phase

STS-127, Space Shuttle Endeavour landing video, 2009

When the approach and landing phase began, the orbiter was at a

3,000 m (9,800 ft) altitude, 12 km (7.5 mi) from the runway. The pilots

applied aerodynamic braking to help slow down the vehicle. The orbiter's

speed was reduced from 682 to 346 km/h (424 to 215 mph), approximately,

at touch-down (compared to 260 km/h or 160 mph for a jet airliner). The

landing gear was deployed while the Orbiter was flying at 430 km/h

(270 mph). To assist the speed brakes, a 12 m (39 ft) drag chute was

deployed either after main gear or nose gear touchdown (depending on

selected chute deploy mode) at about 343 km/h (213 mph). The chute was

jettisoned once the orbiter slowed to 110 km/h (68.4 mph).

- Endeavour brake chute deploys after touching down

Post-landing processing

Discovery after landing on Earth for crew disembarkment

After landing, the vehicle stayed on the runway for several hours for

the orbiter to cool. Teams at the front and rear of the orbiter tested

for presence of hydrogen, hydrazine, monomethylhydrazine, nitrogen tetroxide and ammonia (fuels and by-products of the reaction control system and the orbiter's three APUs).

If hydrogen was detected, an emergency would be declared, the orbiter

powered down and teams would evacuate the area. A convoy of 25 specially

designed vehicles and 150 trained engineers and technicians approached

the orbiter. Purge and vent lines were attached to remove toxic gases

from fuel lines and the cargo bay about 45–60 minutes after landing. A flight surgeon

boarded the orbiter for initial medical checks of the crew before

disembarking. Once the crew left the orbiter, responsibility for the

vehicle was handed from the Johnson Space Center back to the Kennedy

Space Center.

If the mission ended at Edwards Air Force Base in California, White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico, or any of the runways the orbiter might use in an emergency, the orbiter was loaded atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified 747, for transport back to the Kennedy Space Center, landing at the Shuttle Landing Facility.

Once at the Shuttle Landing Facility, the orbiter was then towed 2

miles (3.2 km) along a tow-way and access roads normally used by tour

buses and KSC employees to the Orbiter Processing Facility where it began a months-long preparation process for the next mission.

Landing sites

Atlantis deploys the landing gear before landing.

NASA preferred Space Shuttle landings to be at Kennedy Space Center.

If weather conditions made landing there unfavorable, the Shuttle

could delay its landing until conditions are favorable, touch down at

Edwards Air Force Base, California, or use one of the multiple alternate

landing sites around the world. A landing at any site other than

Kennedy Space Center meant that after touchdown the Shuttle must be

mated to the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft and returned to Cape Canaveral. Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-3) once landed at the White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico; this was viewed as a last resort as NASA scientists believed that the sand could potentially damage the Shuttle's exterior.

There were many alternative landing sites that were never used.

Risk contributors

Discovery at ISS in 2011 (STS-133)

An example of technical risk analysis for a STS mission is SPRA iteration 3.1 top risk contributors for STS-133:

- Micro-Meteoroid Orbital Debris (MMOD) strikes

- Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME)-induced or SSME catastrophic failure

- Ascent debris strikes to TPS leading to LOCV on orbit or entry

- Crew error during entry

- RSRM-induced RSRM catastrophic failure (RSRM are the rocket motors of the SRBs)

- COPV failure (COPV are tanks inside the orbiter that hold gas at high pressure)

An internal NASA risk assessment study (conducted by the Shuttle Program Safety and Mission Assurance Office at Johnson Space Center)

released in late 2010 or early 2011 concluded that the agency had

seriously underestimated the level of risk involved in operating the

Shuttle. The report assessed that there was a 1 in 9 chance of a

catastrophic disaster during the first nine flights of the Shuttle but

that safety improvements had later improved the risk ratio to 1 in 90.

Fleet history

Flight timeline

Major events

OV-101 Enterprise takes flight for the first time over Dryden Flight Research Facility, Edwards, California in 1977 as part of the Shuttle program's Approach and Landing Tests (ALT).

Atlantis lifts off from Launch Pad 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida on the STS-132 mission to the International Space Station at 2:20 pm EDT on May 14, 2010. This was one of the last scheduled flights for Atlantis before it was retired.

STS-135 last Space Shuttle liftoff in slow motion

Below is a list of major events in the Space Shuttle orbiter fleet:

| Date | Orbiter | Major event / remarks |

|---|---|---|

| September 17, 1976 | Enterprise | Prototype Space Shuttle Enterprise was rolled out of its assembly facility in Southern California and displayed before a crowd of several thousand people. |

| February 18, 1977 | Enterprise | First flight; Attached to Shuttle Carrier Aircraft throughout flight. |

| August 12, 1977 | Enterprise | First free flight; Tailcone on; lakebed landing. |

| October 26, 1977 | Enterprise | Final Enterprise free flight; First landing on Edwards AFB concrete runway. |

| April 12, 1981 | Columbia | First Columbia flight, first orbital test flight; STS-1 |

| November 11, 1982 | Columbia | First operational flight of the Space Shuttle, first mission to carry four astronauts; STS-5 |

| April 4, 1983 | Challenger | First Challenger flight; STS-6 |

| August 30, 1984 | Discovery | First Discovery flight; STS-41-D |

| October 3, 1985 | Atlantis | First Atlantis flight; STS-51-J |

| October 30, 1985 | Challenger | First and only crew of eight astronauts; STS-61-A |

| January 28, 1986 | Challenger | Loss of vehicle 73 seconds after launch; STS-51-L; all seven crew members died. |

| September 29, 1988 | Discovery | First post-Challenger mission; STS-26 |

| May 4, 1989 | Atlantis | The first Space Shuttle mission to launch an interplanetary probe, Magellan; STS-30 |

| April 24, 1990 | Discovery | Launch of the Hubble Space Telescope; STS-31 |

| May 7, 1992 | Endeavour | First Endeavour flight; STS-49 |

| November 19, 1996 | Columbia | Longest Shuttle mission at 17 days, 15 hours; STS-80 |

| December 4, 1998 | Endeavour | First ISS mission; STS-88 |

| February 1, 2003 | Columbia | Disintegrated during re-entry; STS-107; all seven crew members died. |

| July 25, 2005 | Discovery | First post-Columbia mission; STS-114 |

| February 24, 2011 | Discovery | Last Discovery flight; STS-133 |

| May 16, 2011 | Endeavour | Last Endeavour mission; STS-134 |

| July 8, 2011 | Atlantis | Last Atlantis flight and last Space Shuttle flight; STS-135 |

Sources: NASA launch manifest, NASA Space Shuttle archive

Disasters

STS-51-L crew: (front row) Michael J. Smith, Dick Scobee, Ronald McNair; (back row) Ellison Onizuka, Christa McAuliffe, Gregory Jarvis, Judith Resnik

On January 28, 1986, Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after

launch due to the failure of the right SRB, killing all seven

astronauts on board. The disaster was caused by low-temperature

impairment of an O-ring, a mission critical seal used between segments

of the SRB casing. Failure of the O-ring allowed hot combustion gases

to escape from between the booster sections and burn through the

adjacent external tank, causing it to explode.

Repeated warnings from design engineers voicing concerns about the lack

of evidence of the O-rings' safety when the temperature was below 53 °F

(12 °C) had been ignored by NASA managers.

On February 1, 2003, Columbia disintegrated during re-entry, killing its crew of seven, because of damage to the carbon-carbon

leading edge of the wing caused during launch. Ground control engineers

had made three separate requests for high-resolution images taken by

the Department of Defense that would have provided an understanding of

the extent of the damage, while NASA's chief thermal protection system (TPS) engineer requested that astronauts on board Columbia

be allowed to leave the vehicle to inspect the damage. NASA managers

intervened to stop the Department of Defense's assistance and refused

the request for the spacewalk, and thus the feasibility of scenarios for astronaut repair or rescue by Atlantis were not considered by NASA management at the time.

Retirement

Atlantis orbiter's final welcome home, 2011

NASA retired the Space Shuttle in 2011, after 30 years of service.

The Shuttle was originally conceived of and presented to the public as a

"Space Truck", which would, among other things, be used to build a

United States space station in low earth orbit

in the early 1990s. When the U.S. space station evolved into the

International Space Station project, which suffered from long delays and

design changes before it could be completed, the retirement of the

Space Shuttle was delayed several times until 2011, serving at least 15

years longer than originally planned. Discovery was the first of NASA's three remaining operational Space Shuttles to be retired.

The final Space Shuttle mission was originally scheduled for late

2010, but the program was later extended to July 2011 when Michael

Suffredini of the ISS program said that one additional trip was needed

in 2011 to deliver parts to the International Space Station.

The Shuttle's final mission consisted of just four

astronauts—Christopher Ferguson (Commander), Douglas Hurley (Pilot),

Sandra Magnus (Mission Specialist 1), and Rex Walheim (Mission

Specialist 2); they conducted the 135th and last space Shuttle mission on board Atlantis, which launched on July 8, 2011, and landed safely at the Kennedy Space Center on July 21, 2011, at 5:57 AM EDT (09:57 UTC).

Distribution of orbiters and other hardware

Space Shuttle Program commemorative patch

NASA announced it would transfer orbiters to education institutions

or museums at the conclusion of the Space Shuttle program. Each museum

or institution is responsible for covering the US$28.8 million

cost of preparing and transporting each vehicle for display. Twenty

museums from across the country submitted proposals for receiving one of

the retired orbiters. NASA also made Space Shuttle thermal protection system tiles available to schools and universities for less than US$25 each. About 7,000 tiles were available on a first-come, first-served basis, limited to one per institution.

Orbiters on display

On April 12, 2011, NASA announced selection of locations for the remaining Shuttle orbiters:

- Atlantis is on display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, near Cape Canaveral, Florida. It was delivered to the Visitor Complex on November 2, 2012.

- Discovery was delivered to the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia, near Washington, D.C. on April 19, 2012. On April 17, 2012, Discovery was flown atop a 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft escorted by a NASA T-38 Talon chase aircraft in a final farewell flight. The 747 and Discovery flew over Washington, D.C. and the metropolitan area around 10 am and arrived at Dulles around 11 am. The flyover and landing were widely covered on national news media.

Endeavour at Los Angeles International Airport

- Endeavour was delivered to the California Science Center in Los Angeles, California on October 14, 2012. It arrived at Los Angeles International Airport on September 21, 2012 escorted by two NASA F/A-18 Hornet chase aircraft, concluding a two-day, cross country journey atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft after stops at Ellington Field in Houston, Biggs Army Airfield in El Paso and the Dryden Flight Research Facility at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

- Enterprise (atmospheric test orbiter) was on display at the National Air and Space Museum's Udvar-Hazy Center but was moved to New York City's Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum in mid-2012.

In August 2011, the NASA Office of Inspector General

(OIG) published a "Review of NASA's Selection of Display Locations for

the Space Shuttle Orbiters"; the review had four main findings:

- "NASA's decisions regarding Orbiter placement were the result of an Agency-created process that emphasized above all other considerations locating the Orbiters in places where the most people would have the opportunity to view them";

- "the Team made several errors during its evaluation process, including one that would have resulted in a numerical 'tie' among the Intrepid, the Kennedy Visitor Complex, and the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force (Air Force Museum) in Dayton, Ohio";

- there is "no evidence that the Team's recommendation or the Administrator's decision were tainted by political influence or any other improper consideration";

- "some of the choices NASA made during the selection process – specifically, its decision to manage aspects of the selection as if it were a competitive procurement and to delay announcement of its placement decisions until April 2011 (more than 2 years after it first solicited information from interested entities)—may intensify challenges to the Agency and the selectees as they work to complete the process of placing the Orbiters in their new homes."

The NASA OIG had three recommendations, saying NASA should:

- "expeditiously review recipients' financial, logistical, and curatorial display plans to ensure they are feasible and consistent with the Agency's educational goals and processing and delivery schedules";

- "ensure that recipient payments are closely coordinated with processing schedules, do not impede NASA's ability to efficiently prepare the Orbiters for museum display, and provide sufficient funds in advance of the work to be performed; and"

- "work closely with the recipient organizations to minimize the possibility of delays in the delivery schedule that could increase the Agency's costs or impact other NASA missions and priorities."

In September 2011, the CEO and two board members of Seattle's Museum of Flight met with NASA Administrator Charles Bolden,

pointing out "significant errors in deciding where to put its four

retiring Space Shuttles"; the errors alleged include inaccurate

information on Museum of Flight's attendance and international visitor

statistics, as well as the readiness of the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum's exhibit site.

Orbiter replicas on display

- Independence, formerly known as Explorer, is a full-scale, high-fidelity replica of the Space Shuttle. It was built by Guard-Lee in Apopka, Florida, installed at Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in 1993, and moved to Space Center Houston in 2012. It was built using schematics, blueprints and archival documents provided by NASA and by shuttle contractors such as Rockwell International. While many of the features on the replica are simulated, some parts, including the landing gear's Michelin tires, have been used in the Space Shuttle program.[110] The model is on display, mounted on top of the original Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (NASA 905) outside of the Visitors' Center.

- Pathfinder (honorary Orbiter Vehicle Designation: OV-098) is a Space Shuttle test simulator made of steel and wood. Constructed by NASA in 1977 as an unnamed test article, it was purchased in the early 1980s by the America-Japan Society, Inc. which had it refurbished, named it, and placed it on display in the Great Space Shuttle Exhibition in Tokyo. The mockup was later returned to the United States and placed on permanent display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, in May 1988.

Hardware on display

Flight and mid-deck training hardware will be taken from the Johnson Space Center and will go to the National Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. The full fuselage mockup, which includes the payload bay and aft section but no wings, is to go to the Museum of Flight in Seattle. Mission Simulation and Training Facility's fixed simulator will go to the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, and the motion simulator will go to the Texas A&M Aerospace Engineering Department in College Station, Texas. Other simulators used in Shuttle astronaut training will go to the Wings of Dreams Aviation Museum in Starke, Florida and the Virginia Air and Space Center in Hampton, Virginia.

Successors and legacy

STS conducted numerous experiments in space, such as this ionization experiment

Sprint cameras, tested by the Shuttle, may be used on ISS and other missions

Until another U.S. manned spacecraft is ready, crews will travel to and from the International Space Station (ISS) exclusively aboard the Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

A planned successor to STS was the "Shuttle II", during the 1980s

and 1990s, and later the Constellation program during the 2004–2010

period. CSTS was a proposal to continue to operate STS commercially,

after NASA. In September 2011, NASA announced the selection of the design for the new Space Launch System that is planned to launch the Orion spacecraft and other hardware to missions beyond low earth-orbit.

The Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program began in 2006 with the purpose of creating commercially operated unmanned cargo vehicles to service the ISS. The Commercial Crew Development

(CCDev) program was started in 2010 to create commercially operated

manned spacecraft capable of delivering at least four crew members to

the ISS, to stay docked for 180 days, and then return them back to

Earth. These spacecraft were to become operational in the 2010s.

In popular culture

Space

Shuttles have been features of fiction and nonfiction, from children's

movies to documentaries. Early examples include the 1979 James Bond film, Moonraker, the 1982 Activision videogame Space Shuttle: A Journey into Space (1982) and G. Harry Stine's 1981 novel Shuttle Down. In the 1986 film SpaceCamp, Atlantis accidentally launches into space with a group of U.S. Space Camp participants as its crew. A space shuttle named Intrepid is featured in the 1989 film Moontrap.

The 1998 film Armageddon

portrays a combined crew of offshore oil rig workers and U.S. military

staff who pilot two modified Shuttles to avert the destruction of Earth

by an asteroid. Retired American test pilots visit a Russian satellite