More probability density is found as one gets closer to the expected (mean) value in a normal distribution. Statistics used in standardized testing assessment are shown. The scales include standard deviations, cumulative percentages, Z-scores, and T-scores.

Scatter plots are used in descriptive statistics to show the observed relationships between different variables.

Statistics is a branch of mathematics dealing with data collection, organization, analysis, interpretation and presentation. In applying statistics to, for example, a scientific, industrial, or social problem, it is conventional to begin with a statistical population or a statistical model

process to be studied. Populations can be diverse topics such as "all

people living in a country" or "every atom composing a crystal".

Statistics deals with all aspects of data, including the planning of

data collection in terms of the design of surveys and experiments.

When census data cannot be collected, statisticians collect data by developing specific experiment designs and survey samples.

Representative sampling assures that inferences and conclusions can

reasonably extend from the sample to the population as a whole. An experimental study

involves taking measurements of the system under study, manipulating

the system, and then taking additional measurements using the same

procedure to determine if the manipulation has modified the values of

the measurements. In contrast, an observational study does not involve experimental manipulation.

Two main statistical methods are used in data analysis: descriptive statistics, which summarize data from a sample using indexes such as the mean or standard deviation, and inferential statistics, which draw conclusions from data that are subject to random variation (e.g., observational errors, sampling variation). Descriptive statistics are most often concerned with two sets of properties of a distribution (sample or population): central tendency (or location) seeks to characterize the distribution's central or typical value, while dispersion (or variability)

characterizes the extent to which members of the distribution depart

from its center and each other. Inferences on mathematical statistics

are made under the framework of probability theory, which deals with the analysis of random phenomena.

A standard statistical procedure involves the test of the relationship

between two statistical data sets, or a data set and synthetic data

drawn from an idealized model. A hypothesis is proposed for the

statistical relationship between the two data sets, and this is compared

as an alternative to an idealized null hypothesis

of no relationship between two data sets. Rejecting or disproving the

null hypothesis is done using statistical tests that quantify the sense

in which the null can be proven false, given the data that are used in

the test. Working from a null hypothesis, two basic forms of error are

recognized: Type I errors (null hypothesis is falsely rejected giving a "false positive") and Type II errors (null hypothesis fails to be rejected and an actual difference between populations is missed giving a "false negative").

Multiple problems have come to be associated with this framework:

ranging from obtaining a sufficient sample size to specifying an

adequate null hypothesis.

Measurement processes that generate statistical data are also

subject to error. Many of these errors are classified as random (noise)

or systematic (bias),

but other types of errors (e.g., blunder, such as when an analyst

reports incorrect units) can also be important. The presence of missing data or censoring may result in biased estimates and specific techniques have been developed to address these problems.

Statistics can be said to have begun in ancient civilization,

going back at least to the 5th century BC, but it was not until the 18th

century that it started to draw more heavily from calculus and probability theory. In more recent years statistics has relied more on statistical software to produce tests such as descriptive analysis.

Scope

Some definitions are:

- Merriam-Webster dictionary defines statistics as "a branch of mathematics dealing with the collection, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of masses of numerical data."

- Statistician Arthur Lyon Bowley defines statistics as "Numerical statements of facts in any department of inquiry placed in relation to each other."

Statistics is a mathematical body of science that pertains to the

collection, analysis, interpretation or explanation, and presentation of

data, or as a branch of mathematics.

Some consider statistics to be a distinct mathematical science rather

than a branch of mathematics. While many scientific investigations make

use of data, statistics is concerned with the use of data in the context

of uncertainty and decision making in the face of uncertainty.

Mathematical statistics

Mathematical statistics is the application of mathematics to statistics. Mathematical techniques used for this include mathematical analysis, linear algebra, stochastic analysis, differential equations, and measure-theoretic probability theory.

Overview

In applying statistics to a problem, it is common practice to start with a population

or process to be studied. Populations can be diverse topics such as

"all people living in a country" or "every atom composing a crystal".

Ideally, statisticians compile data about the entire population (an operation called census). This may be organized by governmental statistical institutes. Descriptive statistics can be used to summarize the population data. Numerical descriptors include mean and standard deviation for continuous data types (like income), while frequency and percentage are more useful in terms of describing categorical data (like race).

When a census is not feasible, a chosen subset of the population called a sample

is studied. Once a sample that is representative of the population is

determined, data is collected for the sample members in an observational

or experimental

setting. Again, descriptive statistics can be used to summarize the

sample data. However, the drawing of the sample has been subject to an

element of randomness, hence the established numerical descriptors from

the sample are also due to uncertainty. To still draw meaningful

conclusions about the entire population, inferential statistics

is needed. It uses patterns in the sample data to draw inferences about

the population represented, accounting for randomness. These inferences

may take the form of: answering yes/no questions about the data (hypothesis testing), estimating numerical characteristics of the data (estimation), describing associations within the data (correlation) and modeling relationships within the data (for example, using regression analysis). Inference can extend to forecasting, prediction and estimation of unobserved values either in or associated with the population being studied; it can include extrapolation and interpolation of time series or spatial data, and can also include data mining.

Data collection

Sampling

When full census data cannot be collected, statisticians collect sample data by developing specific experiment designs and survey samples. Statistics itself also provides tools for prediction and forecasting through statistical models.

The idea of making inferences based on sampled data began around the

mid-1600s in connection with estimating populations and developing

precursors of life insurance.

To use a sample as a guide to an entire population, it is

important that it truly represents the overall population.

Representative sampling

assures that inferences and conclusions can safely extend from the

sample to the population as a whole. A major problem lies in determining

the extent that the sample chosen is actually representative.

Statistics offers methods to estimate and correct for any bias within

the sample and data collection procedures. There are also methods of

experimental design for experiments that can lessen these issues at the

outset of a study, strengthening its capability to discern truths about

the population.

Sampling theory is part of the mathematical discipline of probability theory. Probability is used in mathematical statistics to study the sampling distributions of sample statistics and, more generally, the properties of statistical procedures.

The use of any statistical method is valid when the system or

population under consideration satisfies the assumptions of the method.

The difference in point of view between classic probability theory and

sampling theory is, roughly, that probability theory starts from the

given parameters of a total population to deduce probabilities that pertain to samples. Statistical inference, however, moves in the opposite direction—inductively inferring from samples to the parameters of a larger or total population.

Experimental and observational studies

A common goal for a statistical research project is to investigate causality, and in particular to draw a conclusion on the effect of changes in the values of predictors or independent variables on dependent variables. There are two major types of causal statistical studies: experimental studies and observational studies.

In both types of studies, the effect of differences of an independent

variable (or variables) on the behavior of the dependent variable are

observed. The difference between the two types lies in how the study is

actually conducted. Each can be very effective.

An experimental study involves taking measurements of the system under

study, manipulating the system, and then taking additional measurements

using the same procedure to determine if the manipulation has modified

the values of the measurements. In contrast, an observational study does

not involve experimental manipulation. Instead, data are gathered and correlations between predictors and response are investigated.

While the tools of data analysis work best on data from randomized studies, they are also applied to other kinds of data—like natural experiments and observational studies—for which a statistician would use a modified, more structured estimation method (e.g., Difference in differences estimation and instrumental variables, among many others) that produce consistent estimators.

Experiments

The basic steps of a statistical experiment are:

- Planning the research, including finding the number of replicates of the study, using the following information: preliminary estimates regarding the size of treatment effects, alternative hypotheses, and the estimated experimental variability. Consideration of the selection of experimental subjects and the ethics of research is necessary. Statisticians recommend that experiments compare (at least) one new treatment with a standard treatment or control, to allow an unbiased estimate of the difference in treatment effects.

- Design of experiments, using blocking to reduce the influence of confounding variables, and randomized assignment of treatments to subjects to allow unbiased estimates of treatment effects and experimental error. At this stage, the experimenters and statisticians write the experimental protocol that will guide the performance of the experiment and which specifies the primary analysis of the experimental data.

- Performing the experiment following the experimental protocol and analyzing the data following the experimental protocol.

- Further examining the data set in secondary analyses, to suggest new hypotheses for future study.

- Documenting and presenting the results of the study.

Experiments on human behavior have special concerns. The famous Hawthorne study examined changes to the working environment at the Hawthorne plant of the Western Electric Company. The researchers were interested in determining whether increased illumination would increase the productivity of the assembly line

workers. The researchers first measured the productivity in the plant,

then modified the illumination in an area of the plant and checked if

the changes in illumination affected productivity. It turned out that

productivity indeed improved (under the experimental conditions).

However, the study is heavily criticized today for errors in

experimental procedures, specifically for the lack of a control group and blindness. The Hawthorne effect

refers to finding that an outcome (in this case, worker productivity)

changed due to observation itself. Those in the Hawthorne study became

more productive not because the lighting was changed but because they

were being observed.

Observational study

An

example of an observational study is one that explores the association

between smoking and lung cancer. This type of study typically uses a

survey to collect observations about the area of interest and then

performs statistical analysis. In this case, the researchers would

collect observations of both smokers and non-smokers, perhaps through a cohort study, and then look for the number of cases of lung cancer in each group. A case-control study

is another type of observational study in which people with and without

the outcome of interest (e.g. lung cancer) are invited to participate

and their exposure histories are collected.

Types of data

Various attempts have been made to produce a taxonomy of levels of measurement. The psychophysicist Stanley Smith Stevens

defined nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio scales. Nominal

measurements do not have meaningful rank order among values, and permit

any one-to-one transformation. Ordinal measurements have imprecise

differences between consecutive values, but have a meaningful order to

those values, and permit any order-preserving transformation. Interval

measurements have meaningful distances between measurements defined, but

the zero value is arbitrary (as in the case with longitude and temperature measurements in Celsius or Fahrenheit),

and permit any linear transformation. Ratio measurements have both a

meaningful zero value and the distances between different measurements

defined, and permit any rescaling transformation.

Because variables conforming only to nominal or ordinal

measurements cannot be reasonably measured numerically, sometimes they

are grouped together as categorical variables, whereas ratio and interval measurements are grouped together as quantitative variables, which can be either discrete or continuous, due to their numerical nature. Such distinctions can often be loosely correlated with data type in computer science, in that dichotomous categorical variables may be represented with the Boolean data type, polytomous categorical variables with arbitrarily assigned integers in the integral data type, and continuous variables with the real data type involving floating point

computation. But the mapping of computer science data types to

statistical data types depends on which categorization of the latter is

being implemented.

Other categorizations have been proposed. For example, Mosteller and Tukey (1977) distinguished grades, ranks, counted fractions, counts, amounts, and balances. Nelder (1990) described continuous counts, continuous ratios, count ratios, and categorical modes of data. See also Chrisman (1998), van den Berg (1991).

The issue of whether or not it is appropriate to apply different

kinds of statistical methods to data obtained from different kinds of

measurement procedures is complicated by issues concerning the

transformation of variables and the precise interpretation of research

questions. "The relationship between the data and what they describe

merely reflects the fact that certain kinds of statistical statements

may have truth values which are not invariant under some

transformations. Whether or not a transformation is sensible to

contemplate depends on the question one is trying to answer" (Hand,

2004, p. 82).

Terminology and theory of inferential statistics

Statistics, estimators and pivotal quantities

Consider independent identically distributed (IID) random variables with a given probability distribution: standard statistical inference and estimation theory defines a random sample as the random vector given by the column vector of these IID variables. The population being examined is described by a probability distribution that may have unknown parameters.

A statistic is a random variable that is a function of the random sample, but not a function of unknown parameters. The probability distribution of the statistic, though, may have unknown parameters.

Consider now a function of the unknown parameter: an estimator is a statistic used to estimate such function. Commonly used estimators include sample mean, unbiased sample variance and sample covariance.

A random variable that is a function of the random sample and of the unknown parameter, but whose probability distribution does not depend on the unknown parameter is called a pivotal quantity or pivot. Widely used pivots include the z-score, the chi square statistic and Student's t-value.

Between two estimators of a given parameter, the one with lower mean squared error is said to be more efficient. Furthermore, an estimator is said to be unbiased if its expected value

is equal to the true value of the unknown parameter being estimated,

and asymptotically unbiased if its expected value converges at the limit to the true value of such parameter.

Other desirable properties for estimators include: UMVUE

estimators that have the lowest variance for all possible values of the

parameter to be estimated (this is usually an easier property to verify

than efficiency) and consistent estimators which converges in probability to the true value of such parameter.

This still leaves the question of how to obtain estimators in a

given situation and carry the computation, several methods have been

proposed: the method of moments, the maximum likelihood method, the least squares method and the more recent method of estimating equations.

Null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis

Interpretation of statistical information can often involve the development of a null hypothesis which is usually (but not necessarily) that no relationship exists among variables or that no change occurred over time.

The best illustration for a novice is the predicament encountered by a criminal trial. The null hypothesis, H0, asserts that the defendant is innocent, whereas the alternative hypothesis, H1, asserts that the defendant is guilty. The indictment comes because of suspicion of the guilt. The H0 (status quo) stands in opposition to H1 and is maintained unless H1 is supported by evidence "beyond a reasonable doubt". However, "failure to reject H0"

in this case does not imply innocence, but merely that the evidence was

insufficient to convict. So the jury does not necessarily accept H0 but fails to reject H0. While one can not "prove" a null hypothesis, one can test how close it is to being true with a power test, which tests for type II errors.

What statisticians call an alternative hypothesis is simply a hypothesis that contradicts the null hypothesis.

Error

Working from a null hypothesis, two basic forms of error are recognized:

- Type I errors where the null hypothesis is falsely rejected giving a "false positive".

- Type II errors where the null hypothesis fails to be rejected and an actual difference between populations is missed giving a "false negative".

Standard deviation

refers to the extent to which individual observations in a sample

differ from a central value, such as the sample or population mean,

while Standard error refers to an estimate of difference between sample mean and population mean.

A statistical error is the amount by which an observation differs from its expected value, a residual

is the amount an observation differs from the value the estimator of

the expected value assumes on a given sample (also called prediction).

Mean squared error is used for obtaining efficient estimators, a widely used class of estimators. Root mean square error is simply the square root of mean squared error.

A least squares fit: in red the points to be fitted, in blue the fitted line.

Many statistical methods seek to minimize the residual sum of squares, and these are called "methods of least squares" in contrast to Least absolute deviations.

The latter gives equal weight to small and big errors, while the former

gives more weight to large errors. Residual sum of squares is also differentiable, which provides a handy property for doing regression. Least squares applied to linear regression is called ordinary least squares method and least squares applied to nonlinear regression is called non-linear least squares.

Also in a linear regression model the non deterministic part of the

model is called error term, disturbance or more simply noise. Both

linear regression and non-linear regression are addressed in polynomial least squares,

which also describes the variance in a prediction of the dependent

variable (y axis) as a function of the independent variable (x axis) and

the deviations (errors, noise, disturbances) from the estimated

(fitted) curve.

Measurement processes that generate statistical data are also subject to error. Many of these errors are classified as random (noise) or systematic (bias),

but other types of errors (e.g., blunder, such as when an analyst

reports incorrect units) can also be important. The presence of missing data or censoring may result in biased estimates and specific techniques have been developed to address these problems.

Interval estimation

Confidence intervals: the red line is true value for the mean in this example, the blue lines are random confidence intervals for 100 realizations.

Most studies only sample part of a population, so results don't fully

represent the whole population. Any estimates obtained from the sample

only approximate the population value. Confidence intervals

allow statisticians to express how closely the sample estimate matches

the true value in the whole population. Often they are expressed as 95%

confidence intervals. Formally, a 95% confidence interval for a value is

a range where, if the sampling and analysis were repeated under the

same conditions (yielding a different dataset), the interval would

include the true (population) value in 95% of all possible cases. This

does not imply that the probability that the true value is in the confidence interval is 95%. From the frequentist perspective, such a claim does not even make sense, as the true value is not a random variable.

Either the true value is or is not within the given interval. However,

it is true that, before any data are sampled and given a plan for how

to construct the confidence interval, the probability is 95% that the

yet-to-be-calculated interval will cover the true value: at this point,

the limits of the interval are yet-to-be-observed random variables.

One approach that does yield an interval that can be interpreted as

having a given probability of containing the true value is to use a credible interval from Bayesian statistics: this approach depends on a different way of interpreting what is meant by "probability", that is as a Bayesian probability.

In principle confidence intervals can be symmetrical or

asymmetrical. An interval can be asymmetrical because it works as lower

or upper bound for a parameter (left-sided interval or right sided

interval), but it can also be asymmetrical because the two sided

interval is built violating symmetry around the estimate. Sometimes the

bounds for a confidence interval are reached asymptotically and these

are used to approximate the true bounds.

Significance

Statistics rarely give a simple Yes/No type answer to the question

under analysis. Interpretation often comes down to the level of

statistical significance applied to the numbers and often refers to the

probability of a value accurately rejecting the null hypothesis

(sometimes referred to as the p-value).

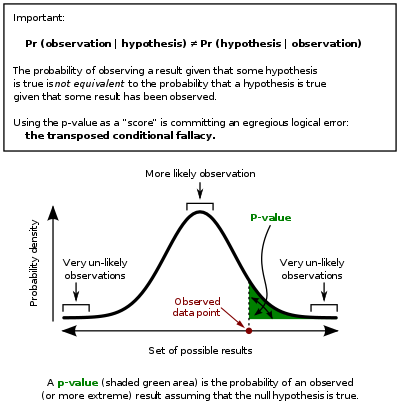

In this graph the black line is probability distribution for the test statistic, the critical region is the set of values to the right of the observed data point (observed value of the test statistic) and the p-value is represented by the green area.

The standard approach is to test a null hypothesis against an alternative hypothesis. A critical region

is the set of values of the estimator that leads to refuting the null

hypothesis. The probability of type I error is therefore the probability

that the estimator belongs to the critical region given that null

hypothesis is true (statistical significance)

and the probability of type II error is the probability that the

estimator doesn't belong to the critical region given that the

alternative hypothesis is true. The statistical power of a test is the probability that it correctly rejects the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis is false.

Referring to statistical significance does not necessarily mean

that the overall result is significant in real world terms. For example,

in a large study of a drug it may be shown that the drug has a

statistically significant but very small beneficial effect, such that

the drug is unlikely to help the patient noticeably.

Although in principle the acceptable level of statistical significance may be subject to debate, the p-value

is the smallest significance level that allows the test to reject the

null hypothesis. This test is logically equivalent to saying that the

p-value is the probability, assuming the null hypothesis is true, of

observing a result at least as extreme as the test statistic. Therefore, the smaller the p-value, the lower the probability of committing type I error.

Some problems are usually associated with this framework:

- A difference that is highly statistically significant can still be of no practical significance, but it is possible to properly formulate tests to account for this. One response involves going beyond reporting only the significance level to include the p-value when reporting whether a hypothesis is rejected or accepted. The p-value, however, does not indicate the size or importance of the observed effect and can also seem to exaggerate the importance of minor differences in large studies. A better and increasingly common approach is to report confidence intervals. Although these are produced from the same calculations as those of hypothesis tests or p-values, they describe both the size of the effect and the uncertainty surrounding it.

- Fallacy of the transposed conditional, aka prosecutor's fallacy: criticisms arise because the hypothesis testing approach forces one hypothesis (the null hypothesis) to be favored, since what is being evaluated is the probability of the observed result given the null hypothesis and not probability of the null hypothesis given the observed result. An alternative to this approach is offered by Bayesian inference, although it requires establishing a prior probability.

- Rejecting the null hypothesis does not automatically prove the alternative hypothesis.

- As everything in inferential statistics it relies on sample size, and therefore under fat tails p-values may be seriously miscomputed.

Examples

Some well-known statistical tests and procedures are:

Misuse

Misuse of statistics

can produce subtle, but serious errors in description and

interpretation—subtle in the sense that even experienced professionals

make such errors, and serious in the sense that they can lead to

devastating decision errors. For instance, social policy, medical

practice, and the reliability of structures like bridges all rely on the

proper use of statistics.

Even when statistical techniques are correctly applied, the

results can be difficult to interpret for those lacking expertise. The statistical significance

of a trend in the data—which measures the extent to which a trend could

be caused by random variation in the sample—may or may not agree with

an intuitive sense of its significance. The set of basic statistical

skills (and skepticism) that people need to deal with information in

their everyday lives properly is referred to as statistical literacy.

There is a general perception that statistical knowledge is all-too-frequently intentionally misused by finding ways to interpret only the data that are favorable to the presenter. A mistrust and misunderstanding of statistics is associated with the quotation, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics". Misuse of statistics can be both inadvertent and intentional, and the book How to Lie with Statistics

outlines a range of considerations. In an attempt to shed light on the

use and misuse of statistics, reviews of statistical techniques used in

particular fields are conducted (e.g. Warne, Lazo, Ramos, and Ritter

(2012)).

Ways to avoid misuse of statistics include using proper diagrams and avoiding bias. Misuse can occur when conclusions are overgeneralized

and claimed to be representative of more than they really are, often by

either deliberately or unconsciously overlooking sampling bias.

Bar graphs are arguably the easiest diagrams to use and understand, and

they can be made either by hand or with simple computer programs.

Unfortunately, most people do not look for bias or errors, so they are

not noticed. Thus, people may often believe that something is true even

if it is not well represented. To make data gathered from statistics believable and accurate, the sample taken must be representative of the whole. According to Huff, "The dependability of a sample can be destroyed by [bias]... allow yourself some degree of skepticism."

To assist in the understanding of statistics Huff proposed a series of questions to be asked in each case:

- Who says so? (Does he/she have an axe to grind?)

- How does he/she know? (Does he/she have the resources to know the facts?)

- What's missing? (Does he/she give us a complete picture?)

- Did someone change the subject? (Does he/she offer us the right answer to the wrong problem?)

- Does it make sense? (Is his/her conclusion logical and consistent with what we already know?)

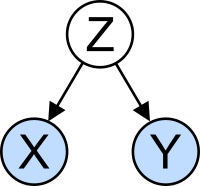

The confounding variable problem: X and Y may be correlated, not because there is causal relationship between them, but because both depend on a third variable Z. Z is called a confounding factor.

Misinterpretation: correlation

The concept of correlation is particularly noteworthy for the potential confusion it can cause. Statistical analysis of a data set

often reveals that two variables (properties) of the population under

consideration tend to vary together, as if they were connected. For

example, a study of annual income that also looks at age of death might

find that poor people tend to have shorter lives than affluent people.

The two variables are said to be correlated; however, they may or may

not be the cause of one another. The correlation phenomena could be

caused by a third, previously unconsidered phenomenon, called a lurking

variable or confounding variable. For this reason, there is no way to immediately infer the existence of a causal relationship between the two variables.

History of statistical science

Gerolamo Cardano, the earliest pioneer on the mathematics of probability.

Some scholars pinpoint the origin of statistics to 1663, with the publication of Natural and Political Observations upon the Bills of Mortality by John Graunt.

Early applications of statistical thinking revolved around the needs of

states to base policy on demographic and economic data, hence its stat- etymology.

The scope of the discipline of statistics broadened in the early 19th

century to include the collection and analysis of data in general.

Today, statistics is widely employed in government, business, and

natural and social sciences.

Its mathematical foundations were laid in the 17th century with the development of the probability theory by Gerolamo Cardano, Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat. Mathematical probability theory arose from the study of games of chance, although the concept of probability was already examined in medieval law and by philosophers such as Juan Caramuel. The method of least squares was first described by Adrien-Marie Legendre in 1805.

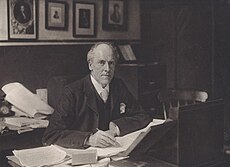

Karl Pearson, a founder of mathematical statistics.

The modern field of statistics emerged in the late 19th and early 20th century in three stages. The first wave, at the turn of the century, was led by the work of Francis Galton and Karl Pearson,

who transformed statistics into a rigorous mathematical discipline used

for analysis, not just in science, but in industry and politics as

well. Galton's contributions included introducing the concepts of standard deviation, correlation, regression analysis

and the application of these methods to the study of the variety of

human characteristics—height, weight, eyelash length among others. Pearson developed the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, defined as a product-moment, the method of moments for the fitting of distributions to samples and the Pearson distribution, among many other things. Galton and Pearson founded Biometrika as the first journal of mathematical statistics and biostatistics (then called biometry), and the latter founded the world's first university statistics department at University College London.

Ronald Fisher coined the term null hypothesis during the Lady tasting tea experiment, which "is never proved or established, but is possibly disproved, in the course of experimentation".

The second wave of the 1910s and 20s was initiated by William Sealy Gosset, and reached its culmination in the insights of Ronald Fisher,

who wrote the textbooks that were to define the academic discipline in

universities around the world. Fisher's most important publications were

his 1918 seminal paper The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance, which was the first to use the statistical term, variance, his classic 1925 work Statistical Methods for Research Workers and his 1935 The Design of Experiments, where he developed rigorous design of experiments models. He originated the concepts of sufficiency, ancillary statistics, Fisher's linear discriminator and Fisher information. In his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection he applied statistics to various biological concepts such as Fisher's principle). Nevertheless, A.W.F. Edwards has remarked that it is "probably the most celebrated argument in evolutionary biology". (about the sex ratio), the Fisherian runaway, a concept in sexual selection about a positive feedback runaway affect found in evolution.

The final wave, which mainly saw the refinement and expansion of

earlier developments, emerged from the collaborative work between Egon Pearson and Jerzy Neyman in the 1930s. They introduced the concepts of "Type II" error, power of a test and confidence intervals. Jerzy Neyman in 1934 showed that stratified random sampling was in general a better method of estimation than purposive (quota) sampling.

Today, statistical methods are applied in all fields that involve

decision making, for making accurate inferences from a collated body of

data and for making decisions in the face of uncertainty based on

statistical methodology. The use of modern computers

has expedited large-scale statistical computations, and has also made

possible new methods that are impractical to perform manually.

Statistics continues to be an area of active research, for example on

the problem of how to analyze Big data.

Applications

Applied statistics, theoretical statistics and mathematical statistics

Applied statistics comprises descriptive statistics and the application of inferential statistics. Theoretical statistics concerns the logical arguments underlying justification of approaches to statistical inference, as well as encompassing mathematical statistics. Mathematical statistics includes not only the manipulation of probability distributions necessary for deriving results related to methods of estimation and inference, but also various aspects of computational statistics and the design of experiments.

Machine learning and data mining

Machine

Learning models are statistical and probabilistic models that captures

patterns in the data through use of computational algorithms.

Statistics in society

Statistics is applicable to a wide variety of academic disciplines, including natural and social sciences, government, and business. Statistical consultants can help organizations and companies that don't have in-house expertise relevant to their particular questions.

Statistical computing

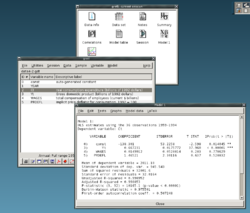

gretl, an example of an open source statistical package

The rapid and sustained increases in computing power starting from

the second half of the 20th century have had a substantial impact on the

practice of statistical science. Early statistical models were almost

always from the class of linear models, but powerful computers, coupled with suitable numerical algorithms, caused an increased interest in nonlinear models (such as neural networks) as well as the creation of new types, such as generalized linear models and multilevel models.

Increased computing power has also led to the growing popularity of computationally intensive methods based on resampling, such as permutation tests and the bootstrap, while techniques such as Gibbs sampling

have made use of Bayesian models more feasible. The computer revolution

has implications for the future of statistics with new emphasis on

"experimental" and "empirical" statistics. A large number of both

general and special purpose statistical software are now available. Examples of available software capable of complex statistical computation include programs such as Mathematica, SAS, SPSS, and R.

Statistics applied to mathematics or the arts

Traditionally,

statistics was concerned with drawing inferences using a

semi-standardized methodology that was "required learning" in most

sciences.

This tradition has changed with use of statistics in non-inferential

contexts. What was once considered a dry subject, taken in many fields

as a degree-requirement, is now viewed enthusiastically. Initially derided by some mathematical purists, it is now considered essential methodology in certain areas.

- In number theory, scatter plots of data generated by a distribution function may be transformed with familiar tools used in statistics to reveal underlying patterns, which may then lead to hypotheses.

- Methods of statistics including predictive methods in forecasting are combined with chaos theory and fractal geometry to create video works that are considered to have great beauty.

- The process art of Jackson Pollock relied on artistic experiments whereby underlying distributions in nature were artistically revealed. With the advent of computers, statistical methods were applied to formalize such distribution-driven natural processes to make and analyze moving video art.

- Methods of statistics may be used predicatively in performance art, as in a card trick based on a Markov process that only works some of the time, the occasion of which can be predicted using statistical methodology.

- Statistics can be used to predicatively create art, as in the statistical or stochastic music invented by Iannis Xenakis, where the music is performance-specific. Though this type of artistry does not always come out as expected, it does behave in ways that are predictable and tunable using statistics.

Specialized disciplines

Statistical techniques are used in a wide range of types of scientific and social research, including: biostatistics, computational biology, computational sociology, network biology, social science, sociology and social research. Some fields of inquiry use applied statistics so extensively that they have specialized terminology. These disciplines include:

- Actuarial science (assesses risk in the insurance and finance industries)

- Applied information economics

- Astrostatistics (statistical evaluation of astronomical data)

- Biostatistics

- Business statistics

- Chemometrics (for analysis of data from chemistry)

- Data mining (applying statistics and pattern recognition to discover knowledge from data)

- Data science

- Demography (statistical study of populations)

- Econometrics (statistical analysis of economic data)

- Energy statistics

- Engineering statistics

- Epidemiology (statistical analysis of disease)

- Geography and geographic information systems, specifically in spatial analysis

- Image processing

- Medical statistics

- Political science

- Psychological statistics

- Reliability engineering

- Social statistics

- Statistical mechanics

In addition, there are particular types of statistical analysis that

have also developed their own specialised terminology and methodology:

- Bootstrap / Jackknife resampling

- Multivariate statistics

- Statistical classification

- Structured data analysis (statistics)

- Structural equation modelling

- Survey methodology

- Survival analysis

- Statistics in various sports, particularly baseball – known as Sabermetrics – and cricket

Statistics form a key basis tool in business and manufacturing as

well. It is used to understand measurement systems variability, control

processes (as in statistical process control

or SPC), for summarizing data, and to make data-driven decisions. In

these roles, it is a key tool, and perhaps the only reliable tool.