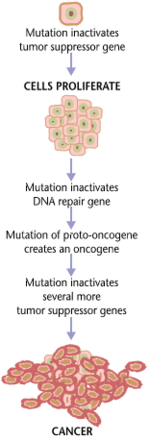

Cancers and tumors are caused by a series of mutations. Each mutation alters the behavior of the cell somewhat.

Carcinogenesis, also called oncogenesis or tumorigenesis, is the formation of a cancer, whereby normal cells are transformed into cancer cells. The process is characterized by changes at the cellular, genetic, and epigenetic levels and abnormal cell division. Cell division is a physiological process that occurs in almost all tissues and under a variety of circumstances. Normally the balance between proliferation and programmed cell death, in the form of apoptosis, is maintained to ensure the integrity of tissues and organs. According to the prevailing accepted theory of carcinogenesis, the somatic mutation theory, mutations in DNA and epimutations

that lead to cancer disrupt these orderly processes by disrupting the

programming regulating the processes, upsetting the normal balance

between proliferation and cell death. This results in uncontrolled cell

division and the evolution of those cells by natural selection in the body. Only certain mutations lead to cancer whereas the majority of mutations do not.

Variants of inherited genes may predispose individuals to cancer. In addition, environmental factors such as carcinogens

and radiation cause mutations that may contribute to the development of

cancer. Finally random mistakes in normal DNA replication may result in

cancer causing mutations.

A series of several mutations to certain classes of genes is usually

required before a normal cell will transform into a cancer cell. On average, for example, 15 "driver mutations" and 60 "passenger" mutations are found in colon cancers. Mutations in genes that regulate cell division, apoptosis (cell death), and DNA repair may result in uncontrolled cell proliferation and cancer.

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of regulation of tissue growth. In order for a normal cell to transform into a cancer cell, genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered. Genetic and epigenetic changes can occur at many levels, from gain or loss of entire chromosomes, to a mutation affecting a single DNA nucleotide, or to silencing or activating a microRNA that controls expression of 100 to 500 genes. There are two broad categories of genes that are affected by these changes. Oncogenes

may be normal genes that are expressed at inappropriately high levels,

or altered genes that have novel properties. In either case, expression

of these genes promotes the malignant phenotype of cancer cells. Tumor suppressor genes

are genes that inhibit cell division, survival, or other properties of

cancer cells. Tumor suppressor genes are often disabled by

cancer-promoting genetic changes. Finally Oncovirinae, viruses that contain an oncogene, are categorized as oncogenic because they trigger the growth of tumorous tissues in the host. This process is also referred to as viral transformation.

Causes

Genetic and epigenetic

There

is a diverse classification scheme for the various genomic changes that

may contribute to the generation of cancer cells. Many of these changes

are mutations, or changes in the nucleotide sequence of genomic DNA. There are also many epigenetic changes that alter whether genes are expressed or not expressed. Aneuploidy,

the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes, is one genomic

change that is not a mutation, and may involve either gain or loss of

one or more chromosomes through errors in mitosis. Large-scale mutations involve the deletion or gain of a portion of a chromosome. Genomic amplification

occurs when a cell gains many copies (often 20 or more) of a small

chromosomal region, usually containing one or more oncogenes and

adjacent genetic material. Translocation

occurs when two separate chromosomal regions become abnormally fused,

often at a characteristic location. A well-known example of this is the Philadelphia chromosome, or translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22, which occurs in chronic myelogenous leukemia, and results in production of the BCR-abl fusion protein, an oncogenic tyrosine kinase. Small-scale mutations include point mutations, deletions, and insertions, which may occur in the promoter of a gene and affect its expression, or may occur in the gene's coding sequence and alter the function or stability of its protein product. Disruption of a single gene may also result from integration of genomic material from a DNA virus or retrovirus, and such an event may also result in the expression of viral oncogenes in the affected cell and its descendants.

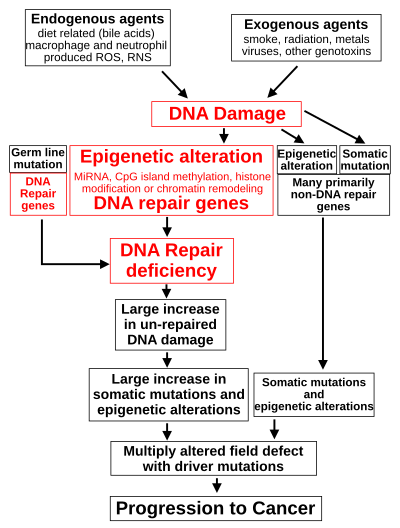

DNA damage

The central role of DNA damage and epigenetic defects in DNA repair genes in carcinogenesis

DNA damage is considered to be the primary cause of cancer.

More than 60,000 new naturally occurring DNA damages arise, on

average, per human cell, per day, due to endogenous cellular processes.

Additional DNA damages can arise from exposure to exogenous agents. As one example of an exogenous

carcinogeneic agent, tobacco smoke causes increased DNA damage, and

these DNA damages likely cause the increase of lung cancer due to

smoking. In other examples, UV light from solar radiation causes DNA damage that is important in melanoma, helicobacter pylori infection produces high levels of reactive oxygen species that damage DNA and contributes to gastric cancer, and the Aspergillus metabolite, aflatoxin, is a DNA damaging agent that is causative in liver cancer.

DNA damages can also be caused by endogenous (naturally

occurring) agents. Macrophages and neutrophils in an inflamed colonic

epithelium are the source of reactive oxygen species causing the DNA

damages that initiate colonic tumorigenesis,

and bile acids, at high levels in the colons of humans eating a high

fat diet, also cause DNA damage and contribute to colon cancer.

Such exogenous and endogenous sources of DNA damage are indicated

in the boxes at the top of the figure in this section. The central role

of DNA damage in progression to cancer is indicated at the second level

of the figure. The central elements of DNA damage, epigenetic alterations and deficient DNA repair in progression to cancer are shown in red.

A deficiency in DNA repair would cause more DNA damages to

accumulate, and increase the risk for cancer. For example, individuals

with an inherited impairment in any of 34 DNA repair genes (see article DNA repair-deficiency disorder) are at increased risk of cancer with some defects causing up to 100% lifetime chance of cancer (e.g. p53 mutations).

Such germ line mutations are shown in a box at the left of the figure,

with an indication of their contribution to DNA repair deficiency.

However, such germline mutations (which cause highly penetrant cancer

syndromes) are the cause of only about 1 percent of cancers.

The majority of cancers are called non-hereditary or "sporadic

cancers". About 30% of sporadic cancers do have some hereditary

component that is currently undefined, while the majority, or 70% of

sporadic cancers, have no hereditary component.

In sporadic cancers, a deficiency in DNA repair is occasionally

due to a mutation in a DNA repair gene, but much more frequently reduced

or absent expression of DNA repair genes is due to epigenetic

alterations that reduce or silence gene expression. This is indicated

in the figure at the 3rd level from the top. For example, for 113

colorectal cancers examined in sequence, only four had a missense mutation in the DNA repair gene MGMT, while the majority had reduced MGMT expression due to methylation of the MGMT promoter region (an epigenetic alteration).

When expression of DNA repair genes is reduced, this causes a DNA

repair deficiency. This is shown in the figure at the 4th level from

the top. With a DNA repair deficiency, more DNA damages remain in cells

at a higher than usual level (5th level from the top in figure), and

these excess damages cause increased frequencies of mutation and/or

epimutation (6th level from top of figure). Experimentally, mutation

rates increase substantially in cells defective in DNA mismatch repair or in Homologous recombinational repair (HRR). Chromosomal rearrangements and aneuploidy also increase in HRR defective cells

During repair of DNA double strand breaks, or repair of other DNA

damages, incompletely cleared sites of repair can cause epigenetic gene

silencing.

The somatic mutations and epigenetic alterations caused by DNA

damages and deficiencies in DNA repair accumulate in field defects.

Field defects are normal appearing tissues with multiple alterations

(discussed in the section below), and are common precursors to

development of the disordered and improperly proliferating clone of

tissue in a cancer. Such field defects (second level from bottom of

figure) may have multiple mutations and epigenetic alterations.

It is impossible to determine the initial cause for most specific

cancers. In a few cases, only one cause exists; for example, the virus

HHV-8 causes all Kaposi's sarcomas. However, with the help of cancer epidemiology techniques and information, it is possible to produce an estimate of a likely cause in many more situations. For example, lung cancer has several causes, including tobacco use and radon gas.

Men who currently smoke tobacco develop lung cancer at a rate 14 times

that of men who have never smoked tobacco, so the chance of lung cancer

in a current smoker being caused by smoking is about 93%; there is a 7%

chance that the smoker's lung cancer was caused by radon gas or some

other, non-tobacco cause.

These statistical correlations have made it possible for researchers

to infer that certain substances or behaviors are carcinogenic. Tobacco

smoke causes increased exogenous

DNA damage, and these DNA damages are the likely cause of lung cancer

due to smoking. Among the more than 5,000 compounds in tobacco smoke,

the genotoxic

DNA damaging agents that occur both at the highest concentrations and

which have the strongest mutagenic effects are acrolein, formaldehyde,

acrylonitrile, 1,3-butadiene, acetaldehyde, ethylene oxide and isoprene.

Using molecular biological

techniques, it is possible to characterize the mutations, epimutations

or chromosomal aberrations within a tumor, and rapid progress is being

made in the field of predicting prognosis

based on the spectrum of mutations in some cases. For example, up to

half of all tumors have a defective p53 gene. This mutation is

associated with poor prognosis, since those tumor cells are less likely

to go into apoptosis or programmed cell death when damaged by therapy. Telomerase mutations remove additional barriers, extending the number of times a cell can divide. Other mutations enable the tumor to grow new blood vessels to provide more nutrients, or to metastasize,

spreading to other parts of the body. However, once a cancer is formed

it continues to evolve and to produce sub clones. For example, a renal

cancer, sampled in 9 areas, had 40 ubiquitous mutations, 59 mutations

shared by some, but not all regions, and 29 "private" mutations only

present in one region.

The cells in which all these DNA alterations accumulate are

difficult to trace, but two recent lines of evidence suggest that normal

stem cells may be the cells of origin in cancers.

First, there exists a highly positive correlation (Spearman’s rho =

0.81; P < 3.5 × 10−8) between the risk of developing cancer in a

tissue and the number of normal stem cell divisions taking place in that

same tissue. The correlation applied to 31 cancer types and extended

across five orders of magnitude.

This correlation means that if the normal stem cells from a tissue

divide once, the cancer risk in that tissue is approximately 1X. If they

divide 1,000 times, the cancer risk is 1,000X. And if the normal stem

cells from a tissue divide 100,000 times, the cancer risk in that tissue

is approximately 100,000X. This strongly suggests that the main reason

we have cancer is that our normal stem cells divide, which implies that

cancer originates in normal stem cells.

Second, statistics show that most human cancers are diagnosed in aged

people. A possible explanation is that cancers occur because cells

accumulate damage through time. DNA is the only cellular component that

can accumulate damage over the entire course of a life, and stem cells

are the only cells that can transmit DNA from the zygote to cells late

in life. Other cells cannot keep DNA from the beginning of life until a

possible cancer occurs. This implies that most cancers arise from normal

stem cells.

Contribution of field defects

Longitudinally

opened freshly resected colon segment showing a cancer and four polyps.

Plus a schematic diagram indicating a likely field defect (a region of

tissue that precedes and predisposes to the development of cancer) in

this colon segment. The diagram indicates sub-clones and sub-sub-clones

that were precursors to the tumors.

The term "field cancerization" was first used in 1953 to describe an

area or "field" of epithelium that has been preconditioned by (at that

time) largely unknown processes so as to predispose it towards

development of cancer.

Since then, the terms "field cancerization" and "field defect" have

been used to describe pre-malignant tissue in which new cancers are

likely to arise.

Field defects have been identified in association with cancers and are important in progression to cancer. However, it was pointed out by Rubin

that "the vast majority of studies in cancer research has been done on

well-defined tumors in vivo, or on discrete neoplastic foci in vitro.

Yet there is evidence that more than 80% of the somatic mutations found

in mutator phenotype human colorectal tumors occur before the onset of

terminal clonal expansion…"

More than half of somatic mutations identified in tumors occurred in a

pre-neoplastic phase (in a field defect), during growth of apparently

normal cells. It would also be expected that many of the epigenetic

alterations present in tumors may have occurred in pre-neoplastic field

defects.

In the colon, a field defect probably arises by natural selection

of a mutant or epigenetically altered cell among the stem cells at the

base of one of the intestinal crypts

on the inside surface of the colon. A mutant or epigenetically altered

stem cell may replace the other nearby stem cells by natural selection.

This may cause a patch of abnormal tissue to arise. The figure in this

section includes a photo of a freshly resected and lengthwise-opened

segment of the colon showing a colon cancer and four polyps. Below the

photo there is a schematic diagram of how a large patch of mutant or

epigenetically altered cells may have formed, shown by the large area in

yellow in the diagram. Within this first large patch in the diagram (a

large clone of cells), a second such mutation or epigenetic alteration

may occur so that a given stem cell acquires an advantage compared to

other stem cells within the patch, and this altered stem cell may expand

clonally forming a secondary patch, or sub-clone, within the original

patch. This is indicated in the diagram by four smaller patches of

different colors within the large yellow original area. Within these new

patches (sub-clones), the process may be repeated multiple times,

indicated by the still smaller patches within the four secondary patches

(with still different colors in the diagram) which clonally expand,

until stem cells arise that generate either small polyps or else a

malignant neoplasm (cancer). In the photo, an apparent field defect in

this segment of a colon has generated four polyps (labeled with the size

of the polyps, 6mm, 5mm, and two of 3mm, and a cancer about 3 cm across

in its longest dimension). These neoplasms are also indicated (in the

diagram below the photo) by 4 small tan circles (polyps) and a larger

red area (cancer). The cancer in the photo occurred in the cecal area

of the colon, where the colon joins the small intestine (labeled) and

where the appendix occurs (labeled). The fat in the photo is external

to the outer wall of the colon. In the segment of colon shown here, the

colon was cut open lengthwise to expose the inner surface of the colon

and to display the cancer and polyps occurring within the inner

epithelial lining of the colon.

If the general process by which sporadic colon cancers arise is

the formation of a pre-neoplastic clone that spreads by natural

selection, followed by formation of internal sub-clones within the

initial clone, and sub-sub-clones inside those, then colon cancers

generally should be associated with, and be preceded by, fields of

increasing abnormality reflecting the succession of premalignant events.

The most extensive region of abnormality (the outermost yellow

irregular area in the diagram) would reflect the earliest event in

formation of a malignant neoplasm.

In experimental evaluation of specific DNA repair deficiencies in

cancers, many specific DNA repair deficiencies were also shown to occur

in the field defects surrounding those cancers. The Table, below,

gives examples for which the DNA repair deficiency in a cancer was shown

to be caused by an epigenetic alteration, and the somewhat lower

frequencies with which the same epigenetically caused DNA repair

deficiency was found in the surrounding field defect.

Some of the small polyps in the field defect shown in the photo of

the opened colon segment may be relatively benign neoplasms. Of polyps

less than 10mm in size, found during colonoscopy and followed with

repeat colonoscopies for 3 years, 25% were unchanged in size, 35%

regressed or shrank in size while 40% grew in size.

Genome instability

Cancers are known to exhibit genome instability or a mutator phenotype. The protein-coding DNA within the nucleus is about 1.5% of the total genomic DNA. Within this protein-coding DNA (called the exome),

an average cancer of the breast or colon can have about 60 to 70

protein altering mutations, of which about 3 or 4 may be "driver"

mutations, and the remaining ones may be "passenger" mutations. However, the average number of DNA sequence mutations in the entire genome (including non-protein-coding regions) within a breast cancer tissue sample is about 20,000. In an average melanoma tissue sample (where melanomas have a higher exome mutation frequency) the total number of DNA sequence mutations is about 80,000.

These high frequencies of mutations in the total nucleotide sequences

within cancers suggest that often an early alteration in the field

defect giving rise to a cancer (e.g. yellow area in the diagram in the

preceding section) is a deficiency in DNA repair. Large field defects

surrounding colon cancers (extending to about 10 cm on each side of a

cancer) are found to frequently have epigenetic defects in 2 or 3 DNA repair proteins (ERCC1, XPF and/or PMS2)

in the entire area of the field defect. When expression of DNA repair

genes is reduced, DNA damages accumulate in cells at a higher than

normal level, and these excess damages cause increased frequencies of

mutation and/or epimutation. Mutation rates strongly increase in cells

defective in DNA mismatch repair or in homologous recombinational repair (HRR). A deficiency in DNA repair, itself, can allow DNA damages to accumulate, and error-prone translesion synthesis

past some of those damages may give rise to mutations. In addition,

faulty repair of these accumulated DNA damages may give rise to

epimutations. These new mutations and/or epimutations may provide a

proliferative advantage, generating a field defect. Although the

mutations/epimutations in DNA repair genes do not, themselves, confer a

selective advantage, they may be carried along as passengers in cells

when the cell acquires an additional mutation/epimutation that does

provide a proliferative advantage.

Non-mainstream theories

There

are a number of theories of carcinogenesis and cancer treatment that

fall outside the mainstream of scientific opinion, due to lack of

scientific rationale, logic, or evidence base. These theories may be

used to justify various alternative cancer treatments. They should be

distinguished from those theories of carcinogenesis that have a logical

basis within mainstream cancer biology, and from which conventionally

testable hypotheses can be made.

Several alternative theories of carcinogenesis, however, are

based on scientific evidence and are increasingly being acknowledged.

Some researchers believe that cancer may be caused by aneuploidy (numerical and structural abnormalities in chromosomes)

rather than by mutations or epimutations. Cancer has also been

considered as a metabolic disease in which the cellular metabolism of

oxygen is diverted from the pathway that generates energy (oxidative phosphorylation) to the pathway that generates reactive oxygen species. This causes an energy switch from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis (Warburg's hypothesis) and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species leading to oxidative stress (oxidative stress theory of cancer).

All these theories of carcinogenesis may be complementary rather than

contradictory. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns – hypermethylation and

hypomethylation compared to normal tissue – have been associated with a

large number of human malignancies.

A number of authors have questioned the assumption that cancers

result from sequential random mutations as oversimplistic, suggesting

instead that cancer results from a failure of the body to inhibit an

innate, programmed proliferative tendency. A related theory developed by astrobiologists suggests that cancer is an atavism, an evolutionary throwback to an earlier form of multicellular life.

The genes responsible for uncontrolled cell growth and cooperation

between cancer cells are very similar to those that enabled the first

multicellular life forms to group together and flourish. These genes

still exist within the genome of more complex metazoans,

such as humans, although more recently evolved genes keep them in

check. When the newer controlling genes fail for whatever reason, the

cell can revert to its more primitive programming and reproduce out of

control. The theory is an alternative to the notion that cancers begin

with rogue cells that undergo evolution within the body. Instead they

possess a fixed number of primitive genes that are progressively

activated, giving them finite variability.

Another evolutionary theory puts the roots of cancer back to the origin

of the eukarote (nucleated) cell by massive horizontal gene transfer,

when the genomes of infecting viruses were cleaved (and thereby

attenuated) by the host, but their fragments integrated into the host

genome as immune protection. Cancer now originates when a rare somatic

mutation recombines such fragments into a functional driver of cell

proliferation.

Cancer cell biology

Tissue can be organized in a continuous spectrum from normal to cancer.

Often, the multiple genetic changes that result in cancer may take

many years to accumulate. During this time, the biological behavior of

the pre-malignant cells slowly change from the properties of normal

cells to cancer-like properties. Pre-malignant tissue can have a

distinctive appearance under the microscope. Among the distinguishing traits are an increased number of dividing cells, variation in nuclear size and shape, variation in cell size and shape, loss of specialized cell features, and loss of normal tissue organization. Dysplasia

is an abnormal type of excessive cell proliferation characterized by

loss of normal tissue arrangement and cell structure in pre-malignant

cells. These early neoplastic changes must be distinguished from hyperplasia, a reversible increase in cell division caused by an external stimulus, such as a hormonal imbalance or chronic irritation.

The most severe cases of dysplasia are referred to as "carcinoma in situ."

In Latin, the term "in situ" means "in place", so carcinoma in situ

refers to an uncontrolled growth of cells that remains in the original

location and has not shown invasion into other tissues. Nevertheless,

carcinoma in situ may develop into an invasive malignancy and is usually

removed surgically, if possible.

Clonal evolution

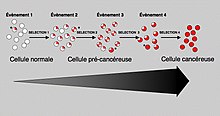

Just like a population of animals undergoes evolution, an unchecked population of cells also can undergo evolution. This undesirable process is called somatic evolution, and is how cancer arises and becomes more malignant.

Most changes in cellular metabolism that allow cells to grow in a

disorderly fashion lead to cell death. However once cancer begins,

cancer cells undergo a process of natural selection:

the few cells with new genetic changes that enhance their survival or

reproduction continue to multiply, and soon come to dominate the growing

tumor, as cells with less favorable genetic change are out-competed. This is exactly how pathogens such as MRSA can become antibiotic-resistant (or how HIV can become drug-resistant), and the same reason why crop blights and pests can become pesticide-resistant. This evolution is why cancer recurrences will have cells that have acquired cancer-drug resistance (or in some cases, resistance to radiation from radiotherapy).

Biological properties of cancer cells

In a 2000 article by Hanahan and Weinberg, the biological properties of malignant tumor cells were summarized as follows:

- Acquisition of self-sufficiency in growth signals, leading to unchecked growth.

- Loss of sensitivity to anti-growth signals, also leading to unchecked growth.

- Loss of capacity for apoptosis, in order to allow growth despite genetic errors and external anti-growth signals.

- Loss of capacity for senescence, leading to limitless replicative potential (immortality)

- Acquisition of sustained angiogenesis, allowing the tumor to grow beyond the limitations of passive nutrient diffusion.

- Acquisition of ability to invade neighbouring tissues, the defining property of invasive carcinoma.

- Acquisition of ability to build metastases at distant sites, the classical property of malignant tumors (carcinomas or others).

The completion of these multiple steps would be a very rare event without :

- Loss of capacity to repair genetic errors, leading to an increased mutation rate (genomic instability), thus accelerating all the other changes.

These biological changes are classical in carcinomas;

other malignant tumors may not need to achieve them all. For example,

tissue invasion and displacement to distant sites are normal properties

of leukocytes; these steps are not needed in the development of leukemia.

The different steps do not necessarily represent individual mutations.

For example, inactivation of a single gene, coding for the p53

protein, will cause genomic instability, evasion of apoptosis and

increased angiogenesis. Not all the cancer cells are dividing. Rather, a

subset of the cells in a tumor, called cancer stem cells, replicate themselves and generate differentiated cells.

Cancer as a defect in cell interactions

Normally,

once a tissue is injured or infected, damaged cells elicit

inflammation, by stimulating specific patterns of enzyme activity and

cytokine gene expression on surrounding cells.

Discrete clusters of molecules are secreted, which act as mediators,

inducing the activity of subsequent cascades of biochemical changes.

Each cytokine binds to specific receptors on various cell types, and

each cell type responds differently by altering the activity of

intracellular signal transduction pathways, depending on the receptors

that the cell expresses and the signaling molecules present inside the

cell.

Collectively, this reprogramming process induces a stepwise change in

cell phenotypes, which will ultimately lead to restoration of tissue

function and toward regaining essential structural integrity.

A tissue can thereby heal, depending on the productive communication

between the cells present at the site of damage, and the immune system.

Key factor in healing is the regulation of cytokine gene expression,

which enables complementary groups of cells to respond to inflammatory

mediators in a manner that gradually produces essential changes in

tissue physiology.

Cancer cells have either permanent (genetic) or reversible (epigenetic)

changes on their genome, which partly inhibit their communication with

surrounding cells and with the immune system.

Cancer cells do not communicate with their tissue microenvironment in a

manner that protects tissue integrity; instead, the movement and the

survival of cancer cells become possible in locations where they can

impair tissue function. Cancer cells survive by rewiring signal pathways that normally protect the tissue from the immune system.

One example for rewiring of tissue function in cancer is the activity of transcription factor NF-κB.

NF-κB activates the expression of numerous genes that are involved in

the transition between inflammation and regeneration, which encode

cytokines, adhesion factors, and other molecules that can change cell

fate. This reprogramming of cellular phenotypes normally allows the development of a fully functional intact tissue.

NF-κB activity is tightly controlled by multiple proteins, which

collectively ensure that only discrete clusters of genes are induced by

NF-κB in a given cell and at a given time.

This tight regulation of signal exchange between cells, protects the

tissue from excessive inflammation, and ensures that different cell

types would gradually acquire complementary functions, and specific

positions. Failure of this mutual regulation between genetic

reprogramming and cell interactions allows cancer cells to give rise to

metastasis. Cancer cells respond aberrantly to cytokines, and activate

signal cascades that can protect them from the immune system.

In fishes

The

role of iodine in marine fishes (rich in iodine) and freshwater fishes

(iodine-deficient) is not completely understood, but it has been

reported that freshwater fishes are more susceptible to infectious and,

in particular, neoplastic and atherosclerotic diseases, of marine

fishes.

Marine elasmobranch fishes such as sharks, stingrays etc. are much less

affected by cancer than freshwater fishes, and therefore have

stimulated medical research to better understand carcinogenesis so it

can be useful in other animals and especially in humans.

Mechanisms

In order for cells to start dividing uncontrollably, genes that regulate cell growth must be dysregulated. Proto-oncogenes are genes that promote cell growth and mitosis, whereas tumor suppressor genes discourage cell growth, or temporarily halt cell division to carry out DNA repair. Typically, a series of several mutations to these genes is required before a normal cell transforms into a cancer cell.

This concept is sometimes termed "oncoevolution." Mutations to these

genes provide the signals for tumor cells to start dividing

uncontrollably. But the uncontrolled cell division that characterizes

cancer also requires that the dividing cell duplicates all its cellular

components to create two daughter cells. The activation of anaerobic

glycolysis (the Warburg effect), which is not necessarily induced by mutations in proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes,

provides most of the building blocks required to duplicate the cellular

components of a dividing cell and, therefore, is also essential for

carcinogenesis.

Oncogenes

Oncogenes promote cell growth through a variety of ways. Many can produce hormones, a "chemical messenger" between cells that encourage mitosis, the effect of which depends on the signal transduction

of the receiving tissue or cells. In other words, when a hormone

receptor on a recipient cell is stimulated, the signal is conducted from

the surface of the cell to the cell nucleus

to affect some change in gene transcription regulation at the nuclear

level. Some oncogenes are part of the signal transduction system itself,

or the signal receptors in cells and tissues themselves, thus controlling the sensitivity to such hormones. Oncogenes often produce mitogens, or are involved in transcription of DNA in protein synthesis, which creates the proteins and enzymes responsible for producing the products and biochemicals cells use and interact with.

Mutations in proto-oncogenes, which are the normally quiescent counterparts of oncogenes, can modify their expression and function, increasing the amount or activity of the product protein. When this happens, the proto-oncogenes become oncogenes, and this transition upsets the normal balance of cell cycle

regulation in the cell, making uncontrolled growth possible. The chance

of cancer cannot be reduced by removing proto-oncogenes from the genome, even if this were possible, as they are critical for growth, repair and homeostasis of the organism. It is only when they become mutated that the signals for growth become excessive.

One of the first oncogenes to be defined in cancer research is the ras oncogene. Mutations in the Ras family of proto-oncogenes (comprising H-Ras, N-Ras and K-Ras) are very common, being found in 20% to 30% of all human tumours.

Ras was originally identified in the Harvey sarcoma virus genome, and

researchers were surprised that not only is this gene present in the

human genome but also, when ligated to a stimulating control element, it

could induce cancers in cell line cultures.

Proto-oncogenes

Proto-oncogenes promote cell growth in a variety of ways. Many can produce hormones, "chemical messengers" between cells that encourage mitosis, the effect of which depends on the signal transduction of the receiving tissue or cells. Some are responsible for the signal transduction system and signal receptors in cells and tissues themselves, thus controlling the sensitivity to such hormones. They often produce mitogens, or are involved in transcription of DNA in protein synthesis, which create the proteins and enzymes responsible for producing the products and biochemicals cells use and interact with.

Mutations in proto-oncogenes can modify their expression and function, increasing the amount or activity of the product protein. When this happens, they become oncogenes,

and, thus, cells have a higher chance of dividing excessively and

uncontrollably. The chance of cancer cannot be reduced by removing

proto-oncogenes from the genome, as they are critical for growth, repair and homeostasis

of the body. It is only when they become mutated that the signals for

growth become excessive.

It is important to note that a gene possessing a growth-promoting role

may increase the carcinogenic potential of a cell, under the condition

that all necessary cellular mechanisms that permit growth are activated.

This condition also includes the inactivation of specific tumor

suppressor genes (see below). If the condition is not fulfilled, the

cell may cease to grow and can proceed to die. This makes identification

of the stage and type of cancer cell that grows under the control of a

given oncogene crucial for the development of treatment strategies.

Tumor suppressor genes

Many tumor suppressor genes effect signal transduction pathways that regulate apoptosis, also known as "programmed cell death".

Tumor suppressor genes code for anti-proliferation signals and proteins that suppress mitosis and cell growth. Generally, tumor suppressors are transcription factors that are activated by cellular stress

or DNA damage. Often DNA damage will cause the presence of

free-floating genetic material as well as other signs, and will trigger

enzymes and pathways that lead to the activation of tumor suppressor genes.

The functions of such genes is to arrest the progression of the cell

cycle in order to carry out DNA repair, preventing mutations from being

passed on to daughter cells. The p53

protein, one of the most important studied tumor suppressor genes, is a

transcription factor activated by many cellular stressors including hypoxia and ultraviolet radiation damage.

Despite nearly half of all cancers possibly involving alterations

in p53, its tumor suppressor function is poorly understood. p53 clearly

has two functions: one a nuclear role as a transcription factor, and

the other a cytoplasmic role in regulating the cell cycle, cell

division, and apoptosis.

The Warburg hypothesis

is the preferential use of glycolysis for energy to sustain cancer

growth. p53 has been shown to regulate the shift from the respiratory to

the glycolytic pathway.

However, a mutation can damage the tumor suppressor gene itself,

or the signal pathway that activates it, "switching it off". The

invariable consequence of this is that DNA repair is hindered or

inhibited: DNA damage accumulates without repair, inevitably leading to

cancer.

Mutations of tumor suppressor genes that occur in germline cells are passed along to offspring,

and increase the likelihood for cancer diagnoses in subsequent

generations. Members of these families have increased incidence and

decreased latency of multiple tumors. The tumor types are typical for

each type of tumor suppressor gene mutation, with some mutations causing

particular cancers, and other mutations causing others. The mode of

inheritance of mutant tumor suppressors is that an affected member

inherits a defective copy from one parent, and a normal copy from the

other. For instance, individuals who inherit one mutant p53 allele (and are therefore heterozygous for mutated p53) can develop melanomas and pancreatic cancer, known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Other inherited tumor suppressor gene syndromes include Rb mutations, linked to retinoblastoma, and APC gene mutations, linked to adenopolyposis colon cancer. Adenopolyposis colon cancer is associated with thousands of polyps in colon while young, leading to colon cancer at a relatively early age. Finally, inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 lead to early onset of breast cancer.

Development of cancer was proposed in 1971 to depend on at least two mutational events. In what became known as the Knudson two-hit hypothesis, an inherited, germ-line mutation in a tumor suppressor gene would cause cancer only if another mutation event occurred later in the organism's life, inactivating the other allele of that tumor suppressor gene.

Usually, oncogenes are dominant, as they contain gain-of-function mutations, while mutated tumor suppressors are recessive, as they contain loss-of-function mutations.

Each cell has two copies of the same gene, one from each parent, and

under most cases gain of function mutations in just one copy of a

particular proto-oncogene is enough to make that gene a true oncogene.

On the other hand, loss of function mutations need to happen in both

copies of a tumor suppressor gene to render that gene completely

non-functional. However, cases exist in which one mutated copy of a tumor suppressor gene can render the other, wild-type copy non-functional. This phenomenon is called the dominant negative effect and is observed in many p53 mutations.

Knudson's two hit model has recently been challenged by several

investigators. Inactivation of one allele of some tumor suppressor genes

is sufficient to cause tumors. This phenomenon is called haploinsufficiency and has been demonstrated by a number of experimental approaches. Tumors caused by haploinsufficiency usually have a later age of onset when compared with those by a two hit process.

Multiple mutations

Multiple mutations in cancer cells

In general, mutations in both types of genes are required for cancer

to occur. For example, a mutation limited to one oncogene would be

suppressed by normal mitosis control and tumor suppressor genes, first hypothesised by the Knudson hypothesis. A mutation to only one tumor suppressor gene would not cause cancer either, due to the presence of many "backup"

genes that duplicate its functions. It is only when enough

proto-oncogenes have mutated into oncogenes, and enough tumor suppressor

genes deactivated or damaged, that the signals for cell growth

overwhelm the signals to regulate it, that cell growth quickly spirals

out of control.

Often, because these genes regulate the processes that prevent most

damage to genes themselves, the rate of mutations increases as one gets

older, because DNA damage forms a feedback loop.

Mutation of tumor suppressor genes that are passed on to the next generation of not merely cells, but their offspring,

can cause increased likelihoods for cancers to be inherited. Members

within these families have increased incidence and decreased latency of

multiple tumors. The mode of inheritance of mutant tumor suppressors is

that affected member inherits a defective copy from one parent, and a

normal copy from another. Because mutations in tumor suppressors act in a

recessive manner (note, however, there are exceptions), the loss of the

normal copy creates the cancer phenotype. For instance, individuals that are heterozygous for p53 mutations are often victims of Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and that are heterozygous for Rb mutations develop retinoblastoma. In similar fashion, mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene are linked to adenopolyposis colon cancer, with thousands of polyps in the colon while young, whereas mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 lead to early onset of breast cancer.

A new idea announced in 2011 is an extreme version of multiple mutations, called chromothripsis

by its proponents. This idea, affecting only 2–3% of cases of cancer,

although up to 25% of bone cancers, involves the catastrophic shattering

of a chromosome into tens or hundreds of pieces and then being patched

back together incorrectly. This shattering probably takes place when

the chromosomes are compacted during normal cell division,

but the trigger for the shattering is unknown. Under this model,

cancer arises as the result of a single, isolated event, rather than the

slow accumulation of multiple mutations.

Non-mutagenic carcinogens

Many mutagens are also carcinogens, but some carcinogens are not mutagens. Examples of carcinogens that are not mutagens include alcohol and estrogen. These are thought to promote cancers through their stimulating effect on the rate of cell mitosis. Faster rates of mitosis increasingly leave fewer opportunities for repair enzymes to repair damaged DNA during DNA replication,

increasing the likelihood of a genetic mistake. A mistake made during

mitosis can lead to the daughter cells' receiving the wrong number of chromosomes, which leads to aneuploidy and may lead to cancer.

Role of infections

Bacterial

Heliobacter pylori is known to cause MALT lymphoma. Other types of bacteria have been implicated in other cancers.

Viral

Furthermore, many cancers originate from a viral infection; this is especially true in animals such as birds, but less so in humans. 12% of human cancers can be attributed to a viral infection. The mode of virally induced tumors can be divided into two, acutely transforming or slowly transforming.

In acutely transforming viruses, the viral particles carry a gene that

encodes for an overactive oncogene called viral-oncogene (v-onc), and

the infected cell is transformed as soon as v-onc is expressed. In

contrast, in slowly transforming viruses, the virus genome is inserted,

especially as viral genome insertion is obligatory part of retroviruses, near a proto-oncogene in the host genome. The viral promoter

or other transcription regulation elements, in turn, cause

over-expression of that proto-oncogene, which, in turn, induces

uncontrolled cellular proliferation. Because viral genome insertion is

not specific to proto-oncogenes and the chance of insertion near that

proto-oncogene is low, slowly transforming viruses have very long tumor

latency compared to acutely transforming virus, which already carries

the viral-oncogene.

Viruses that are known to cause cancer such as HPV (cervical cancer), Hepatitis B (liver cancer), and EBV (a type of lymphoma),

are all DNA viruses. It is thought that when the virus infects a cell,

it inserts a part of its own DNA near the cell growth genes, causing

cell division. The group of changed cells that are formed from the first

cell dividing all have the same viral DNA near the cell growth genes.

The group of changed cells are now special because one of the normal

controls on growth has been lost.

Depending on their location, cells can be damaged through

radiation, chemicals from cigarette smoke, and inflammation from

bacterial infection or other viruses. Each cell has a chance of damage.

Cells often die if they are damaged, through failure of a vital process

or the immune system, however sometimes damage will knock out a single

cancer gene. In an old person, there are thousands, tens of thousands or

hundreds of thousands of knocked-out cells. The chance that any one

would form a cancer is very low.

When the damage occurs in any area of changed cells, something

different occurs. Each of the cells has the potential for growth. The

changed cells will divide quicker when the area is damaged by physical,

chemical, or viral agents. A vicious circle

has been set up: Damaging the area will cause the changed cells to

divide, causing a greater likelihood that they will suffer knock-outs.

This model of carcinogenesis is popular because it explains why

cancers grow. It would be expected that cells that are damaged through

radiation would die or at least be worse off because they have fewer

genes working; viruses increase the number of genes working.

One concern is that we may end up with thousands of vaccines to

prevent every virus that can change our cells. Viruses can have

different effects on different parts of the body. It may be possible to

prevent a number of different cancers by immunizing against one viral

agent. It is likely that HPV, for instance, has a role in cancers of the

mucous membranes of the mouth.

Helminthiasis

Certain parasitic worms are known to be carcinogenic. These include:

- Clonorchis sinensis (the organism causing Clonorchiasis) and Opisthorchis viverrini (causing Opisthorchiasis) are associated with cholangiocarcinoma.

- Schistosoma species (the organisms causing Schistosomiasis) is associated with bladder cancer.

Epigenetics

Epigenetics is the study of the regulation of gene expression through chemical, non-mutational changes in DNA structure. The theory of epigenetics in cancer pathogenesis is that non-mutational changes to DNA can lead to alterations in gene expression. Normally, oncogenes are silent, for example, because of DNA methylation. Loss of that methylation can induce the aberrant expression of oncogenes, leading to cancer pathogenesis. Known mechanisms of epigenetic change include DNA methylation, and methylation or acetylation of histone proteins bound to chromosomal DNA at specific locations. Classes of medications, known as HDAC inhibitors and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, can re-regulate the epigenetic signaling in the cancer cell.

Epimutations include methylations or demethylations of the CpG islands of the promoter regions of genes, which result in repression or de-repression, respectively of gene expression. Epimutations can also occur by acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation or other alterations to histones, creating a histone code that represses or activates gene expression, and such histone epimutations can be important epigenetic factors in cancer. In addition, carcinogenic epimutation can occur through alterations of chromosome architecture caused by proteins such as HMGA2.[103] A further source of epimutation is due to increased or decreased expression of microRNAs

(miRNAs). For example, extra expression of miR-137 can cause

downregulation of expression of 491 genes, and miR-137 is epigenetically

silenced in 32% of colorectal cancers.

Cancer stem cells

A new way of looking at carcinogenesis comes from integrating the ideas of developmental biology into oncology. The cancer stem cell hypothesis proposes that the different kinds of cells in a heterogeneous tumor arise from a single cell, termed Cancer Stem Cell. Cancer stem cells may arise from transformation of adult stem cells or differentiated

cells within a body. These cells persist as a subcomponent of the tumor

and retain key stem cell properties. They give rise to a variety of

cells, are capable of self-renewal and homeostatic control. Furthermore, the relapse of cancer and the emergence of metastasis are also attributed to these cells. The cancer stem cell hypothesis

does not contradict earlier concepts of carcinogenesis. The cancer stem

cell hypothesis has been a proposed mechanism that contributes to tumour heterogeneity.

Clonal evolution

While genetic and epigenetic

alterations in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes change the behavior

of cells, those alterations, in the end, result in cancer through their

effects on the population of neoplastic cells and their microenvironment.

Mutant cells in neoplasms compete for space and resources. Thus, a

clone with a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene or oncogene will expand

only in a neoplasm if that mutation gives the clone a competitive

advantage over the other clones and normal cells in its

microenvironment. Thus, the process of carcinogenesis is formally a process of Darwinian evolution, known as somatic or clonal evolution.

Furthermore, in light of the Darwinistic mechanisms of carcinogenesis,

it has been theorized that the various forms of cancer can be

categorized as pubertarial and gerontological. Anthropological research

is currently being conducted on cancer as a natural evolutionary process

through which natural selection destroys environmentally inferior

phenotypes while supporting others. According to this theory, cancer

comes in two separate types: from birth to the end of puberty

(approximately age 20) teleologically inclined toward supportive group

dynamics, and from mid-life to death (approximately age 40+)

teleologically inclined away from overpopulative group dynamics.