Philanthropy means the love of humanity. A conventional modern definition is "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life", which combines an original humanistic tradition with a social scientific

aspect developed in the 20th century. The definition also serves to

contrast philanthropy with business endeavors, which are private

initiatives for private good, e.g., focusing on material gain, and with

government endeavors, which are public initiatives for public good,

e.g., focusing on provision of public services. A person who practices philanthropy is called a philanthropist.

Philanthropy has distinguishing characteristics separate from charity; not all charity is philanthropy, or vice versa, though there is a recognized degree of overlap in practice. A difference commonly cited is that charity aims to relieve the pain of a particular social problem, whereas philanthropy attempts to address the root cause of the problem—the difference between the proverbial gift of a fish to a hungry person, versus teaching them how to fish.

Philanthropy has distinguishing characteristics separate from charity; not all charity is philanthropy, or vice versa, though there is a recognized degree of overlap in practice. A difference commonly cited is that charity aims to relieve the pain of a particular social problem, whereas philanthropy attempts to address the root cause of the problem—the difference between the proverbial gift of a fish to a hungry person, versus teaching them how to fish.

Etymology

In the second century CE, Plutarch

used the Greek concept of philanthrôpía to describe superior human

beings. During the Roman Catholic Middle Ages, philanthrôpía was

superseded by Caritas charity, selfless love, valued for salvation and

escape from purgatory. Philanthropy was modernized by Sir Francis Bacon

in the 1600s, who is largely credited with preventing the word from

being owned by horticulture. Bacon considered philanthrôpía to be

synonymous with "goodness", correlated with the Aristotelian conception of virtue, as consciously instilled habits of good behaviour. Samuel Johnson simply defined philanthropy as "love of mankind; good nature". This definition still survives today and is often cited more gender-neutrally as the "love of humanity."

Europe

Great Britain

The Foundling Hospital. The building has been demolished.

In London prior to the 18th century, parochial and civic charities

were typically established by bequests and operated by local church

parishes (such as St Dionis Backchurch) or guilds (such as the Carpenters' Company). During the 18th century, however, "a more activist and explicitly Protestant tradition of direct charitable engagement during life" took hold, exemplified by the creation of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and Societies for the Reformation of Manners.

In 1739, Thomas Coram, appalled by the number of abandoned children living on the streets of London, received a royal charter to establish the Foundling Hospital to look after these unwanted orphans in Lamb's Conduit Fields, Bloomsbury.

This was "the first children's charity in the country, and one that

'set the pattern for incorporated associational charities' in general." The hospital "marked the first great milestone in the creation of these new-style charities."

Jonas Hanway, another notable philanthropist of the era, established The Marine Society in 1756 as the first seafarer's charity, in a bid to aid the recruitment of men to the navy.

By 1763, the society had recruited over 10,000 men and it was

incorporated in 1772. Hanway was also instrumental in establishing the Magdalen Hospital

to rehabilitate prostitutes. These organizations were funded by

subscription and run as voluntary associations. They raised public

awareness of their activities through the emerging popular press and

were generally held in high social regard—some charities received state

recognition in the form of the Royal Charter.

19th century

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce,

began to adopt active campaigning roles, where they would champion a

cause and lobby the government for legislative change. This included

organized campaigns against the ill treatment of animals and children

and the campaign that succeeded in ending the slave trade throughout the Empire starting in 1807.

Although there were no slaves allowed in Britain itself, many rich men

owned sugar plantations in the West Indies, and resisted the movement

to buy them out until it finally succeeded in 1833.

Financial donations to organized charities became fashionable

among the middle-class in the 19th century. By 1869 there were over 200

London charities with an annual income, all together, of about £2

million. By 1885, rapid growth had produced over 1000 London charities,

with an income of about £4.5 million. They included a wide range of

religious and secular goals, with the American import, the YMCA

(Young Men's Christian Association) as one of the largest, and many

small ones such as the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association. In

addition to making annual donations, increasingly wealthy industrialists

and financiers left generous sums in their wills. A sample of 466

wills in the 1890s revealed a total wealth of £76 million, of which £20

million was bequeathed to charities. By 1900 London charities enjoyed

an annual income of about £8.5 million.

Led by the energetic Lord Shaftesbury (1801–1885), philanthropists organized themselves. In 1869 they set up the Charity Organisation Society.

It was a federation of district committees, one in each of the 42 Poor

Law divisions. Its central office had experts in coordination and

guidance, thereby maximizing the impact of charitable giving to the

poor. Many of the charities were designed to alleviate the harsh living conditions in the slums. such as the Labourer's Friend Society

founded in 1830. This included the promotion of allotment of land to

labourers for "cottage husbandry" that later became the allotment

movement, and in 1844 it became the first Model Dwellings Company—an

organization that sought to improve the housing conditions of the

working classes by building new homes for them, while at the same time

receiving a competitive rate of return on any investment. This was one

of the first housing associations, a philanthropic endeavor that flourished in the second half of the nineteenth century, brought about by the growth of the middle class. Later associations included the Peabody Trust, and the Guinness Trust. The principle of philanthropic intention with capitalist return was given the label "five per cent philanthropy."

Switzerland

In 1863, the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant used his personal fortune to fund the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, which became the International Committee of the Red Cross. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Dunant personally led Red Cross delegations that treated soldiers. He shared the first Nobel Peace Prize for this work in 1901.

The French Red Cross

played a minor role in the war with Germany (1870–71). After that it

became a major factor in shaping French civil society as a non-religious

humanitarian organization. It was closely tied to the army's Service

de Santé. By 1914 it operated one thousand local committees with

164,000 members, 21,500 trained nurses, and over 27 million francs in

assets.

The International Committee of the Red Cross

(ICRC) played a major role in working with POW's on all sides in World

War II. It was in a cash starved position when the war began in 1939,

but quickly mobilized its national offices set up a Central Prisoner of

War Agency. For example, it provided food, mail and assistance to

365,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers and civilians held captive.

Suspicions, especially by London, of ICRC as too tolerant or even

complicit with Nazi Germany led to its side-lining in favour of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) as the primary humanitarian agency after 1945.

France

In

France, the Pasteur Institute had a monopoly of specialized

microbiological knowledge allowed it to raise money for serum production

from both private and public sources, walking the line between a

commercial pharmaceutical venture and a philanthropic enterprise.

By 1933, at the depth of the Great Depression, the French wanted a welfare state to relieve distress, but did not want new taxes. War veterans

came up with a solution: the new national lottery proved highly popular

to gamblers, while generating the cash needed without raising taxes.

American money proved invaluable. The Rockefeller Foundation

opened an office in Paris and helped design and fund France's modern

public health system, under the National Institute of Hygiene. It also

set up schools to train physicians and nurses.

Germany

The

history of modern philanthropy the European Continent is especially

important in the case of Germany, which became a model for others,

especially regarding the welfare state. The princes and in the various

Imperial states continued traditional efforts, such as monumental

buildings, parks and art collections. Starting in the early 19th

century, the rapidly emerging middle classes made local philanthropy a

major endeavor to establish their legitimate role in shaping society, in

contradistinction to the aristocracy and the military. They

concentrated on support for social welfare institutions, higher

education, and cultural institutions, as well as some efforts to

alleviate the hardships of rapid industrialization. The bourgeoisie

(upper-middle-class) was defeated in its effort to it gain political

control in 1848, but they still had enough money and organizational

skill that could be employed through philanthropic agencies to provide

an alternative powerbase for their world view.

Religion was a divisive element in Germany, as the Protestants,

Catholics and Jews used alternative philanthropic strategies. The

Catholics, for example, continued their medieval practice of using

financial donations in their wills to lighten their punishment in purgatory

after death. The Protestants did not believe in purgatory, but made a

strong commitment to the improvement of their communities here and now.

Conservative Protestants Raised concerns about deviant sexuality,

alcoholism and socialism, as well as illegitimate births. They used

philanthropy to eradicate social evils that were seen as utterly sinful.

All the religious groups used financial endowments, which multiplied

in the number and wealth as Germany grew richer. Each was devoted to a

specific benefit to that religious community. Each had a board of

trustees; these were laymen who donated their time to public service.

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, an upper class Junker,

used his state-sponsored philanthropy, in the form of his invention of

the modern welfare state, to neutralize the political threat posed by

the socialistic labor unions.

The middle classes, however, made the most use of the new welfare

state, in terms of heavy use of museums, gymnasiums (high schools),

universities, scholarships, and hospitals. For example, state funding

for universities and gymnasiums covered only a fraction of the cost;

private philanthropy became the essential ingredient. 19th century

Germany was even more oriented toward civic improvement then Britain or

the United States, when measured in terms of voluntary private funding

for public purposes. Indeed, such German institutions as the

kindergarten, the research university, and the welfare state became

models copied by the Anglo-Saxons.

The heavy human and economic losses of the First World War, the

financial crises of the 1920s, as well as the Nazi regime and other

devastation by 1945, seriously undermined and weakened the opportunities

for widespread philanthropy in Germany. The civil society so

elaborately build up in the 19th century was practically dead by 1945.

However, by the 1950s, as the "economic miracle" was restoring German

prosperity, the old aristocracy was defunct, and middle-class

philanthropy started to return to importance.

War and postwar: Belgium and Eastern Europe

The Commission for Relief in Belgium

(CRB) was an international (predominantly American) organization that

arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern

France during the First World War. It was led by Herbert Hoover.

Between 1914 and 1919, the CRB operated entirely with voluntary efforts

and was able to feed 11,000,000 Belgians by raising the necessary

money, obtaining voluntary contributions of money and food, shipping the

food to Belgium and controlling it there. For example, the CRB shipped

697,116,000 pounds of flour to Belgium.

Biographer George Nash finds that by the end of 1916, Hoover "stood

preeminent in the greatest humanitarian undertaking the world had ever

seen."

Biographer William Leuchtenburg adds, "He had raised and spent

millions of dollars, with trifling overhead and not a penny lost to

fraud. At its peak, his organization was feeding nine million Belgians

and French a day.

When the war ended in late 1918, Hoover took control of the American Relief Administration (ARA), with the mission of food to Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA fed millions.

U.S. government funding for the ARA expired in the summer of 1919, and

Hoover transformed the ARA into a private organization, raising millions

of dollars from private donors. Under the auspices of the ARA, the

European Children's Fund fed millions of starving children. When

attacked for distributing food to Russia, which was under Bolshevik

control, Hoover snapped, "Twenty million people are starving. Whatever

their politics, they shall be fed!"

United States

The first corporation founded in the 13 Colonies was Harvard College (1636), designed primarily to train young men for the clergy. A leading theorist was the Puritan theologian Cotton Mather (1662–1728), who in 1710 published a widely read essay, Bonifacius, or an Essay to Do Good.

Mather worried that the original idealism had eroded, so he advocated

philanthropic benefaction as a way of life. Though his context was

Christian, his idea was also characteristically American and explicitly

Classical, on the threshold of the Enlightenment.

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was an activist and theorist of American philanthropy. He was much influenced by Daniel Defoe's An Essay upon Projects (1697) and Cotton Mather's Bonifacius: an essay upon the good.

(1710). Franklin attempted to motivate his fellow Philadelphians into

projects for the betterment of the city: examples included the Library Company of Philadelphia

(the first American subscription library), the fire department, the

police force, street lighting and a hospital. A world-class physicist

himself, he promoted scientific organizations including the Philadelphia

Academy (1751) – which became the University of Pennsylvania – as well as the American Philosophical Society (1743) to enable scientific researchers from all 13 colonies to communicate.

By the 1820s, newly rich American businessmen were initiating

philanthropic work, especially with respect to private colleges and

hospitals. George Peabody (1795–1869) is the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy. A financier based in Baltimore and London,

in the 1860s he began to endow libraries and museums in the United

States, and also funded housing for poor people in London. His

activities became the model for Andrew Carnegie and many others.

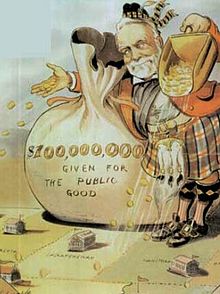

Andrew Carnegie's philanthropy. Puck magazine cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, 1903

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie

(1835–1919) was the most influential leader of philanthropy on a

national (rather than local) scale. After selling his steel corporation

in the 1890s he devoted himself to establishing philanthropic

organizations, and making direct contributions to many educational

cultural and research institutions. His final and largest project was

the Carnegie Corporation of New York, founded in 1911 with a $25 million endowment, later enlarged to $135 million. In all, Carnegie gave away 90% of his fortune.

John D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller in 1885

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century included John D. Rockefeller, Julius Rosenwald (1862–1932) and Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage (1828–1918). Rockefeller (1839–1937) retired from business in the 1890s; he and his son John D. Rockefeller Jr.

(1874–1960) made large-scale national philanthropy systematic,

especially with regard to the study and application of modern medicine,

higher, education and scientific research. Of the $530 million the elder

Rockefeller gave away, $450 million went to medicine. Their leading advisor Frederick Taylor Gates

launched several very large philanthropic projects staffed by experts

who sought to address problems systematically at the roots rather than

let the recipients deal only with their immediate concerns. By 1920, the Rockefeller Foundation

was opening offices in Europe. It launched medical and scientific

projects in Britain, France, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere. It

supported the health projects of the League of Nations. By the 1950s the Rockefeller Foundation was investing heavily in the Green Revolution, especially the work by Norman Borlaug that enabled India, Mexico and many poor countries to dramatically upgrade their agricultural productivity.

Ford Foundation

With the acquisition of most of the stock of the Ford Motor Company

the late 1940s, the Ford Foundation became the largest American

philanthropy, splitting its activities between the United States, and

the rest of the world. Outside the United States, it established a

network of human rights organizations, promoted democracy, gave large

numbers of fellowships for young leaders to study in the United States,

and invested heavily in the Green Revolution,

whereby poor nations dramatically increased their output of rice, wheat

and other foods. Both Ford and Rockefeller were heavily involved.

Ford also gave heavily to build up research universities in Europe and

worldwide. For example, in Italy in 1950 it sent a team to help the

Italian ministry of education reform the nations school system, based on

the principles of ‘meritocracy" (rather than political or family

patronage), democratisation (with universal access to secondary

schools). It reached a compromise between the Christian Democrats and

the Socialists, to help promote uniform treatment and equal outcomes.

The success in Italy became a model for Ford programs and many other

nations.

The Ford Foundation in the 1950s wanted to modernize the legal systems in India and Africa,

by promoting the American model. The plan failed, because of India's

unique legal history, traditions, and profession, as well as its

economic and political conditions. Ford therefore turned to agricultural

reform. The success rate in Africa was no better, and that program closed in 1977.

Oceania

Australia

Philanthropy

in Australia is influenced by the country's regulatory and cultural

history, and by its geography. Structured giving through foundations is

slowly growing, although public data on the philanthropic sector is

sparse.

There is no public registry of philanthropic foundations as distinct

from charities more generally. The sector is represented by

Philanthropy Australia, the peak membership body for grant-making trusts and foundations.

Two foundation types for which some data is available are Private Ancillary Funds (PAFs) and Public Ancillary Funds (PubAFs).

Recent national research supported by the Prime Minister's Community Business Partnership examined giving in Australia, one decade on from the first national study. Giving Australia 2016

provides comprehensive, up-to-date information from individuals,

charitable organisations, philanthropists and businesses in Australia

about giving and volunteering behaviours, approaches and trends.

New Zealand

Philanthropy New Zealand is the peak membership body supporting and representing philanthropy and grantmaking in Aotearoa New Zealand.