Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is a government-sanctioned practice whereby a person is put to death by the state as a punishment for a crime. The sentence ordering that someone be punished in such a manner is referred to as a death sentence, whereas the act of carrying out such a sentence is known as an execution. A prisoner who has been sentenced to death and is awaiting execution is referred to as condemned, and is said to be on death row. Crimes that are punishable by death are known as capital crimes, capital offences or capital felonies, and vary depending on the jurisdiction, but commonly include serious offences such as murder, mass murder, aggravated cases of rape, child rape, child sexual abuse, terrorism, treason, espionage, sedition, offences against the State, such as attempting to overthrow government, piracy, aircraft hijacking, drug trafficking, drug dealing, and drug possession, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, and in some cases, the most serious acts of recidivism, aggravated robbery, and kidnapping.

Etymologically, the term capital (lit. "of the head", derived via the Latin capitalis from caput, "head") in this context alluded to execution by beheading.

Fifty-six countries retain capital punishment, 106 countries have completely abolished it de jure for all crimes, eight have abolished it for ordinary crimes (while maintaining it for special circumstances such as war crimes), and 28 are abolitionist in practice.

Capital punishment is a matter of active controversy in several countries and states, and positions can vary within a single political ideology or cultural region. In the European Union, Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits the use of capital punishment. The Council of Europe, which has 47 member states, has sought to abolish the use of the death penalty by its members absolutely, through Protocol 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights. However, this only affects those member states which have signed and ratified it, and they do not include Armenia, Russia, and Azerbaijan.

The United Nations General Assembly has adopted, in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014, non-binding resolutions calling for a global moratorium on executions, with a view to eventual abolition. Although most nations have abolished capital punishment, over 60% of the world's population live in countries where the death penalty is retained, such as China, India, the United States, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and among almost all Islamic countries, as well as being maintained in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Sri Lanka. China is believed to execute more people than all other countries combined.

History

Anarchist Auguste Vaillant guillotined in France in 1894

Execution of criminals and dissidents has been used by nearly all societies since the beginning of civilizations on Earth.

Until the nineteenth century, without developed prison systems, there

was frequently no workable alternative to ensure deterrence and

incapacitation of criminals. In pre-modern times the executions themselves often involved torture with cruel and painful methods, such as the breaking wheel, keelhauling, sawing, hanging, drawing, and quartering, brazen bull, burning at the stake, flaying, slow slicing, boiling alive, impalement, mazzatello, blowing from a gun, schwedentrunk, blood eagle, and scaphism.

The use of formal execution extends to the beginning of recorded

history. Most historical records and various primitive tribal practices

indicate that the death penalty was a part of their justice system.

Communal punishments for wrongdoing generally included blood money compensation by the wrongdoer, corporal punishment, shunning, banishment and execution. In tribal societies, compensation and shunning were often considered enough as a form of justice. The response to crimes committed by neighbouring tribes, clans or communities included a formal apology, compensation, blood feuds, and tribal warfare.

A blood feud

or vendetta occurs when arbitration between families or tribes fails or

an arbitration system is non-existent. This form of justice was common

before the emergence of an arbitration system based on state or

organized religion. It may result from crime, land disputes or a code of

honour. "Acts of retaliation underscore the ability of the social

collective to defend itself and demonstrate to enemies (as well as

potential allies) that injury to property, rights, or the person will

not go unpunished."

In most countries that practise capital punishment, it is now reserved for murder, terrorism, war crimes, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries sexual crimes, such as rape, fornication, adultery, incest, sodomy, and bestiality carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as Hudud, Zina, and Qisas crimes, such as apostasy (formal renunciation of the state religion), blasphemy, moharebeh, hirabah, Fasad, Mofsed-e-filarz and witchcraft. In many countries that use the death penalty, drug trafficking and often drug possession is also a capital offence. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption and financial crimes are punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offences such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.

Ancient history

Elaborations of tribal arbitration of feuds

included peace settlements often done in a religious context and

compensation system. Compensation was based on the principle of substitution

which might include material (for example, cattle, slaves, land)

compensation, exchange of brides or grooms, or payment of the blood

debt. Settlement rules could allow for animal blood to replace human

blood, or transfers of property or blood money

or in some case an offer of a person for execution. The person offered

for execution did not have to be an original perpetrator of the crime

because the social system was based on tribes and clans, not

individuals. Blood feuds could be regulated at meetings, such as the Norsemen things.

Systems deriving from blood feuds may survive alongside more advanced

legal systems or be given recognition by courts (for example, trial by combat or blood money). One of the more modern refinements of the blood feud is the duel.

Beheading of John the Baptist, woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld, 1860

In certain parts of the world, nations in the form of ancient

republics, monarchies or tribal oligarchies emerged. These nations were

often united by common linguistic, religious or family ties. Moreover,

expansion of these nations often occurred by conquest of neighbouring

tribes or nations. Consequently, various classes of royalty, nobility,

various commoners and slaves emerged. Accordingly, the systems of tribal

arbitration were submerged into a more unified system of justice which

formalized the relation between the different "social classes" rather than "tribes". The earliest and most famous example is Code of Hammurabi which set the different punishment and compensation, according to the different class/group of victims and perpetrators. The Torah (Jewish Law), also known as the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Christian Old Testament), lays down the death penalty for murder, kidnapping, practicing magic, violation of the Sabbath, blasphemy, and a wide range of sexual crimes, although evidence suggests that actual executions were rare.

A further example comes from Ancient Greece, where the Athenian legal system replacing customary oral law was first written down by Draco in about 621 BC: the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes, though Solon later repealed Draco's code and published new laws, retaining capital punishment only for intentional homicide, and only with victim's family permission. The word draconian derives from Draco's laws. The Romans also used the death penalty for a wide range of offences.

China

Although many are executed in the People's Republic of China each year in the present day, there was a time in the Tang dynasty (618–907) when the death penalty was abolished. This was in the year 747, enacted by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang

(r. 712–756). When abolishing the death penalty Xuanzong ordered his

officials to refer to the nearest regulation by analogy when sentencing

those found guilty of crimes for which the prescribed punishment was

execution. Thus depending on the severity of the crime a punishment of

severe scourging with the thick rod or of exile to the remote Lingnan

region might take the place of capital punishment. However, the death

penalty was restored only 12 years later in 759 in response to the An Lushan Rebellion. At this time in the Tang dynasty only the emperor had the authority to sentence criminals to execution. Under Xuanzong capital punishment was relatively infrequent, with only 24 executions in the year 730 and 58 executions in the year 736.

Ling Chi – execution by slow slicing – was a form of torture and execution used in China from roughly AD 900 (Tang era) until it was banned in 1905.

The two most common forms of execution in the Tang dynasty were

strangulation and decapitation, which were the prescribed methods of

execution for 144 and 89 offences respectively. Strangulation was the

prescribed sentence for lodging an accusation against one's parents or

grandparents with a magistrate, scheming to kidnap a person and sell

them into slavery, and opening a coffin while desecrating a tomb.

Decapitation was the method of execution prescribed for more serious

crimes such as treason and sedition. Despite the great discomfort

involved, most of the Tang Chinese preferred strangulation to

decapitation, as a result of the traditional Tang Chinese belief that

the body is a gift from the parents and that it is, therefore,

disrespectful to one's ancestors to die without returning one's body to

the grave intact.

Some further forms of capital punishment were practised in the

Tang dynasty, of which the first two that follow at least were

extralegal. The first of these was scourging to death with the thick rod

which was common throughout the Tang dynasty especially in cases of

gross corruption. The second was truncation, in which the convicted

person was cut in two at the waist with a fodder knife and then left to

bleed to death. A further form of execution called Ling Chi (slow slicing), or death by/of a thousand cuts, was used from the close of the Tang dynasty (around 900) to its abolition in 1905.

When a minister of the fifth grade or above received a death

sentence the emperor might grant him a special dispensation allowing him

to commit suicide in lieu of execution. Even when this privilege was

not granted, the law required that the condemned minister be provided

with food and ale by his keepers and transported to the execution ground

in a cart rather than having to walk there.

Nearly all executions under the Tang dynasty took place in public

as a warning to the population. The heads of the executed were

displayed on poles or spears. When local authorities decapitated a

convicted criminal, the head was boxed and sent to the capital as proof

of identity and that the execution had taken place.

Middle Ages

The burning of Jakob Rohrbach, a leader of the peasants during the German Peasants' War.

The breaking wheel was used during the Middle Ages and was still in use into the 19th century.

In medieval and early modern Europe, before the development of modern prison systems, the death penalty was also used as a generalized form of punishment for even minor offences. During the reign of Henry VIII of England, as many as 72,000 people are estimated to have been executed.

In early modern Europe, a massive moral panic regarding witchcraft

swept across Europe and later the European colonies in North America.

During this period, there were widespread claims that malevolent Satanic witches were operating as an organized threat to Christendom. As a result, tens of thousands of women were prosecuted for witchcraft and executed through the witch trials of the early modern period (between the 15th and 18th centuries).

The death penalty also targeted sexual offences such as sodomy. In England, the Buggery Act 1533 stipulated hanging as punishment for "buggery". James Pratt and John Smith were the last two Englishmen to be executed for sodomy in 1835.

Despite the wide use of the death penalty, calls for reform were not unknown. The 12th century Jewish legal scholar, Moses Maimonides,

wrote, "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty

persons than to put a single innocent man to death." He argued that

executing an accused criminal on anything less than absolute certainty

would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof,

until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice".

Maimonides's concern was maintaining popular respect for law, and he

saw errors of commission as much more threatening than errors of

omission.

Modern era

Antiporta of Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crimes and Punishments), 1766 ed.

In the last several centuries, with the emergence of modern nation states, justice came to be increasingly associated with the concept of natural and legal rights. The period saw an increase in standing police forces and permanent penitential institutions. Rational choice theory, a utilitarian approach to criminology which justifies punishment as a form of deterrence as opposed to retribution, can be traced back to Cesare Beccaria, whose influential treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764) was the first detailed analysis of capital punishment to demand the abolition of the death penalty. In England Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), the founder of modern utilitarianism, called for the abolition of the death penalty. Beccaria, and later Charles Dickens and Karl Marx

noted the incidence of increased violent criminality at the times and

places of executions. Official recognition of this phenomenon led to

executions being carried out inside prisons, away from public view.

In England in the 18th century, when there was no police force,

Parliament drastically increased the number of capital offences to more

than 200. These were mainly property offences, for example cutting down a

cherry tree in an orchard. In 1820, there were 160, including crimes such as shoplifting, petty theft or stealing cattle. The severity of the so-called Bloody Code

was often tempered by juries who refused to convict, or judges, in the

case of petty theft, who arbitrarily set the value stolen at below the

statutory level for a capital crime.

20th century

Mexican execution by firing squad, 1916

In Nazi Germany there were three types of capital punishment; hanging, decapitation and death by shooting. Also, modern military organisations employed capital punishment as a means of maintaining military discipline. In the past, cowardice, absence without leave, desertion, insubordination, shirking under enemy fire and disobeying orders were often crimes punishable by death (see decimation and running the gauntlet). One method of execution, since firearms came into common use, has also been firing squad, although some countries use execution with a single shot to the head or neck.

50 Poles tried and sentenced to death by a Standgericht in retaliation for the assassination of 1 German policeman in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1944

Lithuanian President Antanas Smetona's regime was the first in Europe to sentence Nazis and Communists to death; both were seen as a threat to the Independence of Lithuania.

Various authoritarian states—for example those with Fascist or

Communist governments—employed the death penalty as a potent means of political oppression. According to Robert Conquest, the leading expert on Joseph Stalin's purges, more than one million Soviet citizens were executed during the Great Terror of 1937–38, almost all by a bullet to the back of the head. Mao Zedong publicly stated that "800,000" people had been executed in China during the Cultural Revolution

(1966–1976). Partly as a response to such excesses, civil rights

organizations started to place increasing emphasis on the concept of human rights and an abolition of the death penalty.

Contemporary era

Among countries around the world, all European (except Belarus) and many Oceanian states (including Australia and New Zealand), and Canada have abolished capital punishment. In Latin America, most states have completely abolished the use of capital punishment, while some countries such as Brazil and Guatemala allow for capital punishment only in exceptional situations, such as treason committed during wartime. The United States (the federal government and 29 of the states), some Caribbean countries and the majority of countries in Asia (for example, Japan and India) retain capital punishment. In Africa, less than half of countries retain it, for example Botswana and Zambia. South Africa abolished the death penalty in 1995.

Abolition was often adopted due to political change, as when

countries shifted from authoritarianism to democracy, or when it became

an entry condition for the European Union. The United States is a

notable exception: some states have had bans on capital punishment for

decades, the earliest being Michigan

where it was abolished in 1846, while other states still actively use

it today. The death penalty in the United States remains a contentious

issue which is hotly debated.

In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived when a

miscarriage of justice has occurred though this tends to cause

legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to

abolish the death penalty. In abolitionist countries, the debate is

sometimes revived by particularly brutal murders though few countries

have brought it back after abolishing it. However, a spike in serious,

violent crimes, such as murders or terrorist attacks, has prompted some

countries to effectively end the moratorium on the death penalty. One

notable example is Pakistan which in December 2014 lifted a six-year moratorium on executions after the Peshawar school massacre during which 132 students and 9 members of staff of the Army Public School and Degree College Peshawar were killed by Taliban terrorists. Since then, Pakistan has executed over 400 convicts.

In 2017 two major countries, Turkey and the Philippines, saw their executives making moves to reinstate the death penalty. As of March 2017, passage of the law in the Philippines awaits the Senate's approval.

History of abolition

Peter Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, by Joseph Hickel, 1769

Emperor Shomu banned the death penalty in Japan in 724.

In 724 in Japan, the death penalty was banned during the reign of Emperor Shōmu but only lasted a few years. In 818, Emperor Saga abolished the death penalty in 818 under the influence of Shinto and it lasted until 1156. In China, the death penalty was banned by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang in 747, replacing it with exile or scourging. However, the ban only lasted 12 years.

In England, a public statement of opposition was included in The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, written in 1395. Sir Thomas More's Utopia,

published in 1516, debated the benefits of the death penalty in

dialogue form, coming to no firm conclusion. More was himself executed

for treason in 1535. More recent opposition to the death penalty stemmed

from the book of the Italian Cesare Beccaria Dei Delitti e Delle Pene ("On Crimes and Punishments"),

published in 1764. In this book, Beccaria aimed to demonstrate not only

the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of social welfare, of torture and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg, the future Emperor of Austria, abolished the death penalty in the then-independent Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the first permanent abolition in modern times. On 30 November 1786, after having de facto blocked executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the penal code

that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the

instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000, Tuscany's

regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on 30 November to

commemorate the event. The event is commemorated on this day by 300

cities around the world celebrating Cities for Life Day. In the United Kingdom, it was abolished for murder (leaving only treason, piracy with violence, arson in royal dockyards

and a number of wartime military offences as capital crimes) for a

five-year experiment in 1965 and permanently in 1969, the last execution

having taken place in 1964. It was abolished for all peacetime offences

in 1998.

In the post classical Republic of Poljica life was ensured as a basic right in its Poljica Statute of 1440. The Roman Republic banned capital punishment in 1849. Venezuela followed suit and abolished the death penalty in 1863 and San Marino

did so in 1865. The last execution in San Marino had taken place in

1468. In Portugal, after legislative proposals in 1852 and 1863, the

death penalty was abolished in 1867. The last execution of the death

penalty in Brazil was 1876, from there all the condemnations were

commuted by the Emperor Pedro II

until its abolition for civil offences and military offences in

peacetime in 1891. The penalty for crimes committed in peacetime was

then reinstated and abolished again twice (1938–53 and 1969–78), but on

those occasions it was restricted to acts of terrorism or subversion

considered "internal warfare" and all sentence were commuted and were

not carried out.

Abolition occurred in Canada in 1976 (except for some military offences, with complete abolition in 1998), in France in 1981, and in Australia in 1973 (although the state of Western Australia

retained the penalty until 1984). In 1977, the United Nations General

Assembly affirmed in a formal resolution that throughout the world, it

is desirable to "progressively restrict the number of offences for which

the death penalty might be imposed, with a view to the desirability of

abolishing this punishment".

In the United States, Michigan was the first state to ban the death penalty, on 18 May 1846. The death penalty was declared unconstitutional between 1972 and 1976 based on the Furman v. Georgia case, but the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia

case once again permitted the death penalty under certain

circumstances. Further limitations were placed on the death penalty in Atkins v. Virginia (death penalty unconstitutional for people with an intellectual disability) and Roper v. Simmons

(death penalty unconstitutional if defendant was under age 18 at the

time the crime was committed). In the United States, 21 states and the District of Columbia ban capital punishment.

Many countries have abolished capital punishment either in law or in practice. Since World War II

there has been a trend toward abolishing capital punishment. Capital

punishment has been completely abolished by 102 countries, a further six

have done so for all offences except under special circumstances and 32

more have abolished it in practice because they have not used it for at

least 10 years and are believed to have a policy or established

practice against carrying out executions.

Contemporary use

By country

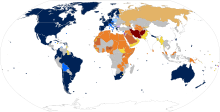

World map of the use of capital punishment as of 26 March 2019

Legend

Retentionist countries: 56

Abolitionist

in practice countries (have not executed anyone during the last 10

years and are believed to have a policy or established practice of not

carrying out executions): 29

Abolitionist countries except for crimes committed under exceptional circumstances (such as crimes committed in wartime): 7

Abolitionist countries: 106

Most countries, including almost all First World nations, have abolished capital punishment either in law or in practice; notable exceptions are the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Additionally, capital punishment is also carried out in China, India, and most Islamic states. The United States is the only Western country to still use the death penalty.

Since World War II,

there has been a trend toward abolishing the death penalty. 58

countries retain the death penalty in active use, 102 countries have

abolished capital punishment altogether, six have done so for all

offences except under special circumstances, and 32 more have abolished

it in practice because they have not used it for at least 10 years and

are believed to have a policy or established practice against carrying

out executions.

According to Amnesty International, 23 countries are known to have performed executions in 2016. There are countries which do not publish information on the use of capital punishment, most significantly China and North Korea. As per Amnesty International, around 1000 prisoners were executed in 2017.

| Country | Total executed (2018) |

|---|---|

| 1,000+ | |

| 253+ | |

| 149 | |

| 85+ | |

| 52+ | |

| 43+ | |

| 25 | |

| 15 | |

| 14+ | |

| 13 | |

| 13 | |

| 7+ | |

| 4+ | |

| 4+ | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| Unknown |

A

map showing U.S. states where the death penalty is authorized for

certain crimes, even if not recently used. The death penalty is also

authorized for certain federal and military crimes.

States with a valid death penalty statute

States without the death penalty

The use of the death penalty is becoming increasingly restrained in some retentionist countries including Taiwan and Singapore. Indonesia carried out no executions between November 2008 and March 2013. Singapore,

Japan and the United States are the only developed countries that are

classified by Amnesty International as 'retentionist' (South Korea is

classified as 'abolitionist in practice'). Nearly all retentionist countries are situated in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. The only retentionist country in Europe is Belarus.

The death penalty was overwhelmingly practised in poor and

authoritarian states, which often employed the death penalty as a tool

of political oppression. During the 1980s, the democratisation of Latin

America swelled the ranks of abolitionist countries.

This was soon followed by the fall of Communism in Europe. Many of the countries which restored democracy aspired to enter the EU. The European Union and the Council of Europe both strictly require member states not to practise the death penalty. Public support for the death penalty in the EU varies. The last execution in a member state of the present-day Council of Europe took place in 1997 in Ukraine.

In contrast, the rapid industrialisation in Asia has seen an increase

in the number of developed countries which are also retentionist. In

these countries, the death penalty retains strong public support, and

the matter receives little attention from the government or the media;

in China there is a small but significant and growing movement to

abolish the death penalty altogether. This trend has been followed by some African and Middle Eastern countries where support for the death penalty remains high.

Some countries have resumed practising the death penalty after

having previously suspended the practice for long periods. The United

States suspended executions in 1972 but resumed them in 1976; there was

no execution in India between 1995 and 2004; and Sri Lanka declared an end to its moratorium on the death penalty on 20 November 2004, although it has not yet performed any further executions. The Philippines re-introduced the death penalty in 1993 after abolishing it in 1987, but again abolished it in 2006.

The United States and Japan are the only developed countries to

have recently carried out executions. The U.S. federal government, the

U.S. military, and 31 states have a valid death penalty statute, and

over 1,400 executions have been carried in the United States since it

reinstated the death penalty in 1976. Japan has 112 inmates with

finalized death sentences as of December 26, 2019, after executing Wei

Wei, a former student from China who was charged with killing and

robbing the Japanese family of four, including children aged 8 and 11,

in 2003.

The most recent country to abolish the death penalty was Burkina Faso in June 2018.

Modern-day public opinion

The public opinion on the death penalty varies considerably by

country and by the crime in question. Countries where a majority of

people are against execution include Norway, where only 25% are in

favour. Most French, Finns, and Italians also oppose the death penalty. A 2016 Gallup poll shows that 60% of Americans support the death penalty, down from 64% in 2010, 65% in 2006, and 68% in 2001.

The support and sentencing of capital punishment has been growing in India in the 2010s due to anger over several recent brutal cases of rape, even though actual executions are comparatively rare.

While support for the death penalty for murder is still high in China,

executions have dropped precipitously, with 3,000 executed in 2012

versus 12,000 in 2002. A poll in South Africa, where capital punishment is abolished, found that 76% of millennial South Africans support re-introduction of the death penalty due to increasing incidents of rape and murder.

A 2017 poll found younger Mexicans are more likely to support capital punishment than older ones.

57% of Brazilians support the death penalty. The age group that shows

the greatest support for execution of those condemned is the 25 to

34-year-old category, in which 61% say they are in favor.

Juvenile offenders

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime although the legal or accepted definition of juvenile offender may vary from one jurisdiction to another) has become increasingly rare. Considering the Age of Majority

is still not 18 in some countries or has not been clearly defined in

law, since 1990 ten countries have executed offenders who were

considered juveniles at the time of their crimes: The People's Republic

of China (PRC), Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United States, and Yemen. The PRC, Pakistan, the United States, Yemen and Iran have since raised the minimum age to 18.

Amnesty International has recorded 61 verified executions since then,

in several countries, of both juveniles and adults who had been

convicted of committing their offences as juveniles. The PRC does not allow for the execution of those under 18, but child executions have reportedly taken place.

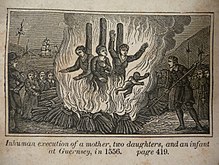

Mother

Catherine Cauchés (center) and her two daughters Guillemine Gilbert

(left) and Perotine Massey (right) with her infant son burning for

heresy

One of the youngest children ever to be executed was the infant son

of Perotine Massey on or around 18 July 1556. His mother was one of the Guernsey Martyrs

who was executed for heresy, and his father had previously fled the

island. At less than one day old, he was ordered to be burned by Bailiff

Hellier Gosselin, with the advice of priests nearby who said the boy

should burn due to having inherited moral stain from his mother, who had

given birth during her execution.

Starting in 1642 within the then British American colonies until present day, an estimated 365

juvenile offenders were executed by the British Colonial authorities

and subsequently by State authorities and the federal government of the

United States. The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005).

In Prussia, children under the age of 14 were exempted from the death penalty in 1794. The capital punishment was cancelled by the Electorate of Bavaria in 1751 for children under the age of 11 and by the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1813 for children and youth under 16 years. In Prussia, the exemption was extended to youth under the age of 16 in 1851. For the first time, all juveniles were excluded for the death penalty by the North German Confederation in 1870, which was continued by the German Empire in 1872. In Nazi Germany, capital punishment was reinstated for juveniles between 16 and 17 years in 1939. This was broadened to children and youth from age 12 to 17 in 1943. The death penalty for juveniles was abolished by West Germany, also generally, in 1949 and by East Germany in 1952.

In the Hereditary Lands, Austrian Silesia, Bohemia and Moravia within the Habsburg Monarchy, capital punishment for children under the age of 11 was no longer foreseen by 1768.

The death penalty was, also for juveniles, nearly abolished in 1787

except for emergency or military law, which is unclear in regard of

those. It was reintroduced for juveniles above 14 years by 1803, where it was kept by general criminal law in 1852 and this exemption was also introduced by the same year and similarly the exemption in the military law by 1855 into all of the Austrian Empire.

In the Helvetic Republic,

the death penalty for children and youth under the age of 16 was

abolished in 1799 but the country was already dissolved in 1803.

Between 2005 and May 2008, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan

and Yemen were reported to have executed child offenders, the largest

number occurring in Iran.

During Hassan Rouhani's

current tenure as president of Iran since 2013, at least 3,602 death

sentences have been carried out. This includes the executions of 34

juvenile offenders.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles under article 37(a), has been signed by all countries and subsequently ratified by all signatories with the exceptions of Somalia and the United States (despite the US Supreme Court decisions abolishing the practice). The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to a jus cogens of customary international law. A majority of countries are also party to the U.N. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

(whose Article 6.5 also states that "Sentence of death shall not be

imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of

age...").

Iran, despite its ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,

was the world's largest executioner of juvenile offenders, for which it

has been the subject of broad international condemnation; the country's

record is the focus of the Stop Child Executions Campaign.

But on 10 February 2012, Iran's parliament changed controversial laws

relating to the execution of juveniles. In the new legislation the age

of 18 (solar year) would be applied to accused of both genders and

juvenile offenders must be sentenced pursuant to a separate law

specifically dealing with juveniles.

Based on the Islamic law which now seems to have been revised, girls at

the age of 9 and boys at 15 of lunar year (11 days shorter than a solar

year) are deemed fully responsible for their crimes. Iran accounted for two-thirds of the global total of such executions, and currently has approximately 140 people considered as juveniles awaiting execution for crimes committed (up from 71 in 2007). The past executions of Mahmoud Asgari, Ayaz Marhoni

and Makwan Moloudzadeh became the focus of Iran's child capital

punishment policy and the judicial system that hands down such

sentences.

Saudi Arabia also executes criminals who were minors at the time of the offence. In 2013, Saudi Arabia was the center of an international controversy after it executed Rizana Nafeek, a Sri Lankan domestic worker, who was believed to have been 17 years old at the time of the crime. Saudi Arabia banned execution for minors, except for terrorism cases, in April 2020.

Japan has not executed juvenile criminals after August 1997, when they executed Norio Nagayama, a spree killer who had been convicted of shooting four people dead in the late 1960s. Nagayama's case created the eponymously named Nagayama standards,

which take into account factors such as the number of victims,

brutality and social impact of the crimes. The standards have been used

in determining whether to apply the death sentence in murder cases. Teruhiko Seki,

convicted of murdering four family members including a 4-year-old

daughter and raping a 15-year-old daughter of a family in 1992, became

the second inmate to be hanged for a crime committed as a minor in the

first such execution in 20 years after Nagayama on 19 December 2017. Takayuki Otsuki,

who was convicted of raping and strangling a 23-year-old woman and

subsequently strangling her 11-month-old daughter to death on 14 April

1999, when he was 18, is another inmate sentenced to death, and his

request for retrial has been rejected by the Supreme Court of Japan.

There is evidence that child executions are taking place in the parts of Somalia controlled by the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). In October 2008, a girl, Aisha Ibrahim Dhuhulow was buried up to her neck at a football stadium, then stoned to death in front of more than 1,000 people. Somalia's established Transitional Federal Government announced in November 2009 (reiterated in 2013) that it plans to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This move was lauded by UNICEF as a welcome attempt to secure children's rights in the country.

Methods

The following methods of execution were used by various countries in 2019:

- Hanging (Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Sudan, Pakistan, Palestinian National Authority, Yemen, Egypt, India, Myanmar, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Syria, UAE, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Liberia, Chad)

- Shooting (the People's Republic of China, Republic of China, Vietnam, Belarus, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, North Korea, Indonesia, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Yemen, and in the US states of Oklahoma and Utah).

- Lethal injection (United States, Guatemala, Thailand, the People's Republic of China, Vietnam)

- Beheading (Saudi Arabia)

- Stoning (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Nigeria, Sudan, Iran)

- Electrocution and gas inhalation (some U.S. states, but only if the prisoner requests it or if lethal injection is unavailable)

- Inert gas asphyxiation (Some U.S states, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama)

Public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of

the general public may voluntarily attend". This definition excludes the

presence of a small number of witnesses randomly selected to assure

executive accountability.

While today the great majority of the world considers public executions

to be distasteful and most countries have outlawed the practice,

throughout much of history executions were performed publicly as a means

for the state to demonstrate "its power before those who fell under its

jurisdiction be they criminals, enemies, or political opponents".

Additionally, it afforded the public a chance to witness "what was

considered a great spectacle".

Social historians note that beginning in the 20th century in the

U.S. and western Europe death in general became increasingly shielded

from public view, occurring more and more behind the closed doors of the

hospital. Executions were likewise moved behind the walls of the penitentiary. The last formal public executions occurred in 1868 in Britain, in 1936 in the U.S. and in 1939 in France.

According to Amnesty International, in 2012, "public executions were known to have been carried out in Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia and Somalia". There have been reports of public executions carried out by state and non-state actors in Hamas-controlled Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen. Executions which can be classified as public were also carried out in the U.S. states of Florida and Utah as of 1992.

Capital crime

Crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity such as genocide

are usually punishable by death in countries retaining capital

punishment. Death sentences for such crimes were handed down and carried

out during the Nuremberg Trials in 1946 and the Tokyo Trials in 1948, but the current International Criminal Court does not use capital punishment. The maximum penalty available to the International Criminal Court is life imprisonment.

Murder

Intentional homicide is punishable by death in most countries

retaining capital punishment, but generally provided it involves an aggravating factor required by statute or judicial precedents.

Drug trafficking

A sign at the Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport warns arriving travelers that drug trafficking is a capital crime in the Republic of China (photo taken in 2005)

Many countries provide the death penalty for drug trafficking, drug dealing, drug possession and related offences, mostly in Asia and some African countries. Among countries who regularly execute drug offenders are China, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Singapore.

Other offences

Other crimes that are punishable by death in some countries include terrorism, treason, espionage, crimes against the state, such as attempting to overthrow government (most countries with the death penalty), political protests (Saudi Arabia), rape (China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Brunei, etc.), economic crimes (China, Iran), human trafficking (China), corruption (China, Iran), kidnapping (China, Bangladesh etc.), separatism (China), adultery (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, Qatar, Brunei, etc.), bestiality (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Iran), sodomy (Saudi Arabia, Iran, UAE, Qatar, Brunei, Nigeria etc.), and religious Hudud offences such as apostasy (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Sudan, etc.), blasphemy (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Nigeria), Moharebeh (Iran), drinking alcohol (Iran), Witchcraft and Sorcery (Saudi Arabia), arson (Algeria, Tunisia, Mali, Mauritania etc.), and hirabah/brigandage/armed and/or aggravated robbery, (Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kenya, Zambia, Ghana, Ethiopia, etc.).

Controversy and debate

Capital punishment is controversial. Death penalty opponents regard the death penalty as inhumane and criticize it for its irreversibility. They argue also that capital punishment lacks deterrent effect, discriminates against minorities and the poor, and that it encourages a "culture of violence". There are many organizations worldwide, such as Amnesty International, and country-specific, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), that have abolition of the death penalty as a fundamental purpose.

Advocates of the death penalty argue that it deters crime, is a good tool for police and prosecutors in plea bargaining, makes sure that convicted criminals do not offend again, and is a just penalty.

Retribution

Execution of a war criminal in 1946

Supporters of the death penalty argued that death penalty is morally

justified when applied in murder especially with aggravating elements

such as for murder of police officers, child murder, torture murder, multiple homicide and mass killing such as terrorism, massacre and genocide. This argument is strongly defended by New York Law School's Professor Robert Blecker, who says that the punishment must be painful in proportion to the crime. Eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant

defended a more extreme position, according to which every murderer

deserves to die on the grounds that loss of life is incomparable to any

jail term.

Some abolitionists argue that retribution is simply revenge and

cannot be condoned. Others while accepting retribution as an element of

criminal justice nonetheless argue that life without parole

is a sufficient substitute. It is also argued that the punishing of a

killing with another death is a relatively unique punishment for a

violent act, because in general violent crimes are not punished by

subjecting the perpetrator to a similar act (e.g. rapists are not

punished by corporal punishment).

Human rights

Abolitionists believe capital punishment is the worst violation of human rights, because the right to life is the most important, and capital punishment violates it without necessity and inflicts to the condemned a psychological torture. Human rights activists oppose the death penalty, calling it "cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment". Amnesty International considers it to be "the ultimate irreversible denial of Human Rights". Albert Camus wrote in a 1956 book called Reflections on the Guillotine, Resistance, Rebellion & Death:

An execution is not simply death. It is just as different from the privation of life as a concentration camp is from prison. [...] For there to be an equivalency, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death on him and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster is not encountered in private life.

In the classic doctrine of natural rights as expounded by for instance Locke and Blackstone, on the other hand, it is an important idea that the right to life can be forfeited. As John Stuart Mill explained in a speech given in Parliament against an amendment to abolish capital punishment for murder in 1868:

And we may imagine somebody asking how we can teach people not to inflict suffering by ourselves inflicting it? But to this I should answer – all of us would answer – that to deter by suffering from inflicting suffering is not only possible, but the very purpose of penal justice. Does fining a criminal show want of respect for property, or imprisoning him, for personal freedom? Just as unreasonable is it to think that to take the life of a man who has taken that of another is to show want of regard for human life. We show, on the contrary, most emphatically our regard for it, by the adoption of a rule that he who violates that right in another forfeits it for himself, and that while no other crime that he can commit deprives him of his right to live, this shall.

Non-painful execution

Trends in most of the world have long been to move to private and less painful executions. France developed the guillotine for this reason in the final years of the 18th century, while Britain banned hanging, drawing, and quartering in the early 19th century. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by kicking a stool or a bucket, which causes death by suffocation, was replaced by long drop "hanging" where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar, Shah of Persia (1896–1907) introduced throat-cutting and blowing from a gun

(close-range cannon fire) as quick and relatively painless alternatives

to more torturous methods of executions used at that time. In the United States, electrocution and gas inhalation were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging, but have been almost entirely superseded by lethal injection. A small number of countries still employ slow hanging methods, decapitation, and stoning.

A study of executions carried out in the United States between

1977 and 2001 indicated that at least 34 of the 749 executions, or 4.5%,

involved "unanticipated problems or delays that caused, at least

arguably, unnecessary agony for the prisoner or that reflect gross

incompetence of the executioner". The rate of these "botched executions"

remained steady over the period of the study. A separate study published in The Lancet in 2005 found that in 43% of cases of lethal injection, the blood level of hypnotics was insufficient to guarantee unconsciousness. However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2008 (Baze v. Rees) and again in 2015 (Glossip v. Gross) that lethal injection does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

Wrongful execution

Capital punishment was abolished in the United Kingdom in part because of the case of Timothy Evans, who was executed in 1950 after being wrongfully convicted of two murders that had in fact been committed by his neighbour.

It is frequently argued that capital punishment leads to miscarriage of justice through the wrongful execution of innocent persons. Many people have been proclaimed innocent victims of the death penalty.

Some have claimed that as many as 39 executions have been carried

out in the face of compelling evidence of innocence or serious doubt

about guilt in the US from 1992 through 2004. Newly available DNA evidence prevented the pending execution of more than 15 death row inmates during the same period in the US, but DNA evidence is only available in a fraction of capital cases. As of 2017,

159 prisoners on death row have been exonerated by DNA or other

evidence, which is seen as an indication that innocent prisoners have

almost certainly been executed.

The National Coalition to

Abolish the Death Penalty claims that between 1976 and 2015, 1,414

prisoners in the United States have been executed while 156 sentenced to

death have had their death sentences vacated, indicating that more than

one in ten death row inmates were wrongly sentenced.

It is impossible to assess how many have been wrongly executed, since

courts do not generally investigate the innocence of a dead defendant,

and defense attorneys tend to concentrate their efforts on clients whose

lives can still be saved; however, there is strong evidence of

innocence in many cases.

Improper procedure may also result in unfair executions. For example, Amnesty International argues that in Singapore "the Misuse of Drugs Act

contains a series of presumptions which shift the burden of proof from

the prosecution to the accused. This conflicts with the universally

guaranteed right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty".

Singapore's Misuse of Drugs Act presumes one is guilty of possession of

drugs if, as examples, one is found to be present or escaping from a

location "proved or presumed to be used for the purpose of smoking or

administering a controlled drug", if one is in possession of a key to a

premises where drugs are present, if one is in the company of another

person found to be in possession of illegal drugs, or if one tests

positive after being given a mandatory urine drug screening.

Urine drug screenings can be given at the discretion of police, without

requiring a search warrant. The onus is on the accused in all of the

above situations to prove that they were not in possession of or

consumed illegal drugs.

Racial, ethnic and social class bias

Opponents of the death penalty argue that this punishment is being

used more often against perpetrators from racial and ethnic minorities

and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, than against those criminals

who come from a privileged background; and that the background of the

victim also influences the outcome.

Researchers have shown that white Americans are more likely to support

the death penalty when told that it is mostly applied to African

Americans,

and that more stereotypically black-looking or darkskinned defendants

are more likely to be sentenced to death if the case involves a white

victim.

In Alabama in 2019, a death row inmate named Domineque Ray was

denied his imam in the room during his execution, instead only offered a

Christian chaplain.

After filing a complaint, a federal court of appeals ruled 5–4 against

Ray's request. The majority cited the "last-minute" nature of the

request, and the dissent stated that the treatment went against the core

principle of denominational neutrality.

In July 2019, two Shiite men, Ali Hakim al-Arab, 25, and Ahmad al-Malali, 24, were executed in Bahrain, despite the protests from the United Nations and rights group. Amnesty International stated that the executions were being carried out on confessions of “terrorism crimes” that were obtained through torture.

International views

Same-sex intercourse illegal:

Death penalty in legislation, but not applied

The United Nations introduced a resolution during the General Assembly's 62nd sessions in 2007 calling for a universal ban.

The approval of a draft resolution by the Assembly's third committee,

which deals with human rights issues, voted 99 to 52, with 33

abstentions, in favour of the resolution on 15 November 2007 and was put

to a vote in the Assembly on 18 December.

Again in 2008, a large majority of states from all regions

adopted, on 20 November in the UN General Assembly (Third Committee), a

second resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of the death

penalty; 105 countries voted in favour of the draft resolution, 48 voted

against and 31 abstained.

A range of amendments proposed by a small minority of pro-death

penalty countries were overwhelmingly defeated. It had in 2007 passed a

non-binding resolution (by 104 to 54, with 29 abstentions) by asking its

member states for "a moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing

the death penalty".

Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union affirms the prohibition on capital punishment in the EU

A number of regional conventions prohibit the death penalty, most

notably, the Sixth Protocol (abolition in time of peace) and the 13th

Protocol (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights. The same is also stated under the Second Protocol in the American Convention on Human Rights,

which, however has not been ratified by all countries in the Americas,

most notably Canada and the United States. Most relevant operative

international treaties do not require its prohibition for cases of

serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

This instead has, in common with several other treaties, an optional

protocol prohibiting capital punishment and promoting its wider

abolition.

Several international organizations have made the abolition of

the death penalty (during time of peace) a requirement of membership,

most notably the European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe. The EU and the Council of Europe are willing to accept a moratorium as an interim measure. Thus, while Russia

is a member of the Council of Europe, and the death penalty remains

codified in its law, it has not made use of it since becoming a member

of the Council – Russia has not executed anyone since 1996. With the

exception of Russia (abolitionist in practice), Kazakhstan (abolitionist for ordinary crimes only), and Belarus (retentionist), all European countries are classified as abolitionist.

Latvia abolished de jure the death penalty for war crimes in 2012, becoming the last EU member to do so.

The Protocol no.13 calls for the abolition of the death penalty

in all circumstances (including for war crimes). The majority of

European countries have signed and ratified it. Some European countries

have not done this, but all of them except Belarus and Kazakhstan have

now abolished the death penalty in all circumstances (de jure, and Russia de facto). Poland is the most recent country to ratify the protocol, on 28 August 2013.

Signatories to the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR: parties in dark green, signatories in light green, non-members in grey

The Protocol no.6 which prohibits the death penalty during peacetime

has been ratified by all members of the European Council, except Russia

(which has signed, but not ratified).

There are also other international abolitionist instruments, such as the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which has 81 parties;

and the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish

the Death Penalty (for the Americas; ratified by 13 states).

In Turkey, over 500 people were sentenced to death after the 1980 Turkish coup d'état. About 50 of them were executed, the last one 25 October 1984. Then there was a de facto moratorium on the death penalty in Turkey. As a move towards EU membership, Turkey made some legal changes. The death penalty was removed from peacetime law by the National Assembly in August 2002, and in May 2004 Turkey amended its constitution

in order to remove capital punishment in all circumstances. It ratified

Protocol no. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights in February

2006. As a result, Europe is a continent free of the death penalty in

practice, all states but Russia, which has entered a moratorium, having

ratified the Sixth Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights,

with the sole exception of Belarus, which is not a member of the Council of Europe. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

has been lobbying for Council of Europe observer states who practise

the death penalty, the U.S. and Japan, to abolish it or lose their

observer status. In addition to banning capital punishment for EU member

states, the EU has also banned detainee transfers in cases where the

receiving party may seek the death penalty.

Sub-Saharan African countries that have recently abolished the death penalty include Burundi, which abolished the death penalty for all crimes in 2009, and Gabon which did the same in 2010. On 5 July 2012, Benin

became part of the Second Optional Protocol to the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibits the use

of the death penalty.

The newly created South Sudan

is among the 111 UN member states that supported the resolution passed

by the United Nations General Assembly that called for the removal of

the death penalty, therefore affirming its opposition to the practice.

South Sudan, however, has not yet abolished the death penalty and stated

that it must first amend its Constitution, and until that happens it

will continue to use the death penalty.

Among non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch

are noted for their opposition to capital punishment. A number of such

NGOs, as well as trade unions, local councils and bar associations

formed a World Coalition Against the Death Penalty in 2002.

Religious views

The world's major faiths have differing views depending on the religion, denomination, sect and/or the individual adherent. As an example, the world's largest Christian denomination, Catholicism, opposes capital punishment in all cases, whereas both the Baha'i and Islamic faiths support capital punishment.