Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and airbrushes, can be used.

In art, the term painting describes both the act and the result of the action (the final work is called "a painting"). The support for paintings includes such surfaces as walls, paper, canvas, wood, glass, lacquer, pottery, leaf, copper and concrete, and the painting may incorporate multiple other materials, including sand, clay, paper, plaster, gold leaf, and even whole objects.

Painting is an important form in the visual arts, bringing in elements such as drawing, composition, gesture (as in gestural painting), narration (as in narrative art), and abstraction. Paintings can be naturalistic and representational (as in still life and landscape painting), photographic, abstract, narrative, symbolistic (as in Symbolist art), emotive (as in Expressionism), and/or political in nature (as in Artivism).

A portion of the history of painting in both Eastern and Western art is dominated by religious art. Examples of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery, to Biblical scenes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, to scenes from the life of Buddha (or other images of Eastern religious origin).

Elements of painting

Color and tone

Color, made up of hue, saturation, and value, dispersed over a surface is the essence of painting, just as pitch and rhythm are the essence of music. Color is highly subjective, but has observable psychological effects, although these can differ from one culture to the next. Black is associated with mourning in the West, but in the East, white is. Some painters, theoreticians, writers, and scientists, including Goethe, Kandinsky, and Newton, have written their own color theory.

Moreover, the use of language is only an abstraction for a color equivalent. The word "red", for example, can cover a wide range of variations from the pure red of the visible spectrum of light. There is not a formalized register of different colors in the way that there is agreement on different notes in music, such as F or C♯. For a painter, color is not simply divided into basic (primary) and derived (complementary or mixed) colors (like red, blue, green, brown, etc.).

Painters deal practically with pigments, so "blue" for a painter can be any of the blues: phthalocyanine blue, Prussian blue, indigo, Cobalt blue, ultramarine, and so on. Psychological and symbolical meanings of color are not, strictly speaking, means of painting. Colors only add to the potential, derived context of meanings, and because of this, the perception of a painting is highly subjective. The analogy with music is quite clear—sound in music (like a C note) is analogous to "light" in painting, "shades" to dynamics, and "coloration" is to painting as the specific timbre of musical instruments is to music. These elements do not necessarily form a melody (in music) of themselves; rather, they can add different contexts to it.

Non-traditional elements

Modern artists have extended the practice of painting considerably to include, as one example, collage, which began with Cubism and is not painting in the strict sense. Some modern painters incorporate different materials such as metal, plastic, sand, cement, straw, leaves or wood for their texture. Examples of this are the works of Jean Dubuffet and Anselm Kiefer. There is a growing community of artists who use computers to "paint" color onto a digital "canvas" using programs such as Adobe Photoshop, Corel Painter, and many others. These images can be printed onto traditional canvas if required.

Rhythm

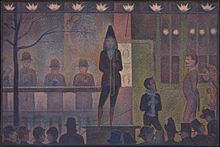

Jean Metzinger's mosaic-like Divisionist technique had its parallel in literature; a characteristic of the alliance between Symbolist writers and Neo-Impressionist artists:

I ask of divided brushwork not the objective rendering of light, but iridescences and certain aspects of color still foreign to painting. I make a kind of chromatic versification and for syllables, I use strokes which, variable in quantity, cannot differ in dimension without modifying the rhythm of a pictorial phraseology destined to translate the diverse emotions aroused by nature. (Jean Metzinger, circa 1907)

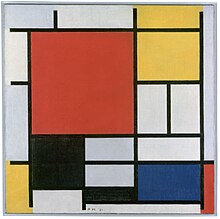

Rhythm, for artists such as Piet Mondrian, is important in painting as it is in music. If one defines rhythm as "a pause incorporated into a sequence", then there can be rhythm in paintings. These pauses allow creative force to intervene and add new creations—form, melody, coloration. The distribution of form or any kind of information is of crucial importance in the given work of art, and it directly affects the aesthetic value of that work. This is because the aesthetic value is functionality dependent, i.e. the freedom (of movement) of perception is perceived as beauty. Free flow of energy, in art as well as in other forms of "techne", directly contributes to the aesthetic value.

Music was important to the birth of abstract art since music is abstract by nature—it does not try to represent the exterior world, but expresses in an immediate way the inner feelings of the soul. Wassily Kandinsky often used musical terms to identify his works; he called his most spontaneous paintings "improvisations" and described more elaborate works as "compositions". Kandinsky theorized that "music is the ultimate teacher," and subsequently embarked upon the first seven of his ten Compositions. Hearing tones and chords as he painted, Kandinsky theorized that (for example), yellow is the color of middle C on a brassy trumpet; black is the color of closure, and the end of things; and that combinations of colors produce vibrational frequencies, akin to chords played on a piano. In 1871 the young Kandinsky learned to play the piano and cello. Kandinsky's stage design for a performance of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition illustrates his "synaesthetic" concept of a universal correspondence of forms, colors and musical sounds.

Music defines much of modernist abstract painting. Jackson Pollock underscores that interest with his 1950 painting Autumn Rhythm (Number 30).

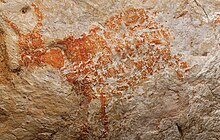

History

Until 2018, the oldest known paintings were believed to be about 32,000 years old, at the Grotte Chauvet in France. They are engraved and painted using red ochre and black pigment, and they show horses, rhinoceros, lions, buffalo, mammoth, abstract designs and what are possibly partial human figures. Cave paintings were then found in Indonesia in the Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave believed to be 40,000 years old. However, the earliest evidence of the act of painting has been discovered in two rock-shelters in Arnhem Land, in northern Australia. In the lowest layer of material at these sites, there are used pieces of ochre estimated to be 60,000 years old. Archaeologists have also found a fragment of rock painting preserved in a limestone rock-shelter in the Kimberley region of North-Western Australia, that is dated 40,000 years old. There are examples of cave paintings all over the world—in Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, China, Australia, Mexico, etc. In Western cultures, oil painting and watercolor painting have rich and complex traditions in style and subject matter. In the East, ink and color ink historically predominated the choice of media, with equally rich and complex traditions.

The invention of photography had a major impact on painting. In the decades after the first photograph was produced in 1829, photographic processes improved and became more widely practiced, depriving painting of much of its historic purpose to provide an accurate record of the observable world. A series of art movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—notably Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, and Dadaism—challenged the Renaissance view of the world. Eastern and African painting, however, continued a long history of stylization and did not undergo an equivalent transformation at the same time.

Modern and Contemporary art has moved away from the historic value of craft and documentation in favour of concept. This has not deterred the majority of living painters from continuing to practice painting either as a whole or part of their work. The vitality and versatility of painting in the 21st century defy the previous "declarations" of its demise. In an epoch characterized by the idea of pluralism, there is no consensus as to a representative style of the age. Artists continue to make important works of art in a wide variety of styles and aesthetic temperaments—their merits are left to the public and the marketplace to judge.

Aesthetics and theory

Aesthetics is the study of art and beauty; it was an important issue for 18th- and 19th-century philosophers such as Kant and Hegel. Classical philosophers like Plato and Aristotle also theorized about art and painting in particular. Plato disregarded painters (as well as sculptors) in his philosophical system; he maintained that painting cannot depict the truth—it is a copy of reality (a shadow of the world of ideas) and is nothing but a craft, similar to shoemaking or iron casting. By the time of Leonardo, painting had become a closer representation of the truth than painting was in Ancient Greece. Leonardo da Vinci, on the contrary, said that "Italian: La Pittura è cosa mentale" ("English: painting is a thing of the mind"). Kant distinguished between Beauty and the Sublime, in terms that clearly gave priority to the former. Although he did not refer to painting in particular, this concept was taken up by painters such as J.M.W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich.

Hegel recognized the failure of attaining a universal concept of beauty and, in his aesthetic essay, wrote that painting is one of the three "romantic" arts, along with Poetry and Music, for its symbolic, highly intellectual purpose. Painters who have written theoretical works on painting include Kandinsky and Paul Klee. In his essay, Kandinsky maintains that painting has a spiritual value, and he attaches primary colors to essential feelings or concepts, something that Goethe and other writers had already tried to do.

Iconography is the study of the content of paintings, rather than their style. Erwin Panofsky and other art historians first seek to understand the things depicted, before looking at their meaning for the viewer at the time, and finally analyzing their wider cultural, religious, and social meaning.

In 1890, the Parisian painter Maurice Denis famously asserted: "Remember that a painting—before being a warhorse, a naked woman or some story or other—is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order." Thus, many 20th-century developments in painting, such as Cubism, were reflections on the means of painting rather than on the external world—nature—which had previously been its core subject. Recent contributions to thinking about painting have been offered by the painter and writer Julian Bell. In his book What is Painting?, Bell discusses the development, through history, of the notion that paintings can express feelings and ideas. In Mirror of The World, Bell writes:

A work of art seeks to hold your attention and keep it fixed: a history of art urges it onwards, bulldozing a highway through the homes of the imagination.

Painting media

Different types of paint are usually identified by the medium that the pigment is suspended or embedded in, which determines the general working characteristics of the paint, such as viscosity, miscibility, solubility, drying time, etc.

Oil

Oil painting is the process of painting with pigments that are bound with a medium of drying oil, such as linseed oil, which was widely used in early modern Europe. Often the oil was boiled with a resin such as pine resin or even frankincense; these were called 'varnishes' and were prized for their body and gloss. Oil paint eventually became the principal medium used for creating artworks as its advantages became widely known. The transition began with Early Netherlandish painting in northern Europe, and by the height of the Renaissance oil painting techniques had almost completely replaced tempera paints in the majority of Europe.

Pastel

Pastel is a painting medium in the form of a stick, consisting of pure powdered pigment and a binder. The pigments used in pastels are the same as those used to produce all colored art media, including oil paints; the binder is of a neutral hue and low saturation. The color effect of pastels is closer to the natural dry pigments than that of any other process. Because the surface of a pastel painting is fragile and easily smudged, its preservation requires protective measures such as framing under glass; it may also be sprayed with a fixative. Nonetheless, when made with permanent pigments and properly cared for, a pastel painting may endure unchanged for centuries. Pastels are not susceptible, as are paintings made with a fluid medium, to the cracking and discoloration that result from changes in the color, opacity, or dimensions of the medium as it dries.

Acrylic

Acrylic paint is fast drying paint containing pigment suspension in acrylic polymer emulsion. Acrylic paints can be diluted with water, but become water-resistant when dry. Depending on how much the paint is diluted (with water) or modified with acrylic gels, media, or pastes, the finished acrylic painting can resemble a watercolor or an oil painting, or have its own unique characteristics not attainable with other media. The main practical difference between most acrylics and oil paints is the inherent drying time. Oils allow for more time to blend colors and apply even glazes over under-paintings. This slow drying aspect of oil can be seen as an advantage for certain techniques, but may also impede the artist's ability to work quickly.

Watercolor

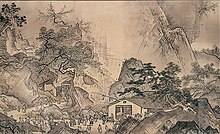

Watercolor is a painting method in which the paints are made of pigments suspended in a water-soluble vehicle. The traditional and most common support for watercolor paintings is paper; other supports include papyrus, bark papers, plastics, vellum or leather, fabric, wood and canvas. In East Asia, watercolor painting with inks is referred to as brush painting or scroll painting. In Chinese, Korean, and Japanese painting it has been the dominant medium, often in monochrome black or browns. India, Ethiopia and other countries also have long traditions. Finger-painting with watercolor paints originated in China. Watercolor pencils (water-soluble color pencils) may be used either wet or dry.

Ink

Ink paintings are done with a liquid that contains pigments and/or dyes and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing with a pen, brush, or quill. Ink can be a complex medium, composed of solvents, pigments, dyes, resins, lubricants, solubilizers, surfactants, particulate matter, fluorescers, and other materials. The components of inks serve many purposes; the ink's carrier, colorants, and other additives control flow and thickness of the ink and its appearance when dry.

Hot wax or encaustic

Encaustic painting, also known as hot wax painting, involves using heated beeswax to which colored pigments are added. The liquid/paste is then applied to a surface—usually prepared wood, though canvas and other materials are often used. The simplest encaustic mixture can be made from adding pigments to beeswax, but there are several other recipes that can be used—some containing other types of waxes, damar resin, linseed oil, or other ingredients. Pure, powdered pigments can be purchased and used, though some mixtures use oil paints or other forms of pigment. Metal tools and special brushes can be used to shape the paint before it cools, or heated metal tools can be used to manipulate the wax once it has cooled onto the surface. Other materials can be encased or collaged into the surface, or layered, using the encaustic medium to adhere it to the surface.

The technique was the normal one for ancient Greek and Roman panel paintings, and remained in use in the Eastern Orthodox icon tradition.

Fresco

Fresco is any of several related mural painting types, done on plaster on walls or ceilings. The word fresco comes from the Italian word affresco [afˈfresːko], which derives from the Latin word for fresh. Frescoes were often made during the Renaissance and other early time periods. Buon fresco technique consists of painting in pigment mixed with water on a thin layer of wet, fresh lime mortar or plaster, for which the Italian word for plaster, intonaco, is used. A secco painting, in contrast, is done on dry plaster (secco is "dry" in Italian). The pigments require a binding medium, such as egg (tempera), glue or oil to attach the pigment to the wall.

Gouache

Gouache is a water-based paint consisting of pigment and other materials designed to be used in an opaque painting method. Gouache differs from watercolor in that the particles are larger, the ratio of pigment to water is much higher, and an additional, inert, white pigment such as chalk is also present. This makes gouache heavier and more opaque, with greater reflective qualities. Like all watermedia, it is diluted with water.

Enamel

Enamels are made by painting a substrate, typically metal, with powdered glass; minerals called color oxides provide coloration. After firing at a temperature of 750–850 degrees Celsius (1380–1560 degrees Fahrenheit), the result is a fused lamination of glass and metal. Unlike most painted techniques, the surface can be handled and wetted Enamels have traditionally been used for decoration of precious objects, but have also been used for other purposes. Limoges enamel was the leading centre of Renaissance enamel painting, with small religious and mythological scenes in decorated surrounds, on plaques or objects such as salts or caskets. In the 18th century, enamel painting enjoyed a vogue in Europe, especially as a medium for portrait miniatures. In the late 20th century, the technique of porcelain enamel on metal has been used as a durable medium for outdoor murals.

Spray paint

Aerosol paint (also called spray paint) is a type of paint that comes in a sealed pressurized container and is released in a fine spray mist when depressing a valve button. A form of spray painting, aerosol paint leaves a smooth, evenly coated surface. Standard sized cans are portable, inexpensive and easy to store. Aerosol primer can be applied directly to bare metal and many plastics.

Speed, portability and permanence also make aerosol paint a common graffiti medium. In the late 1970s, street graffiti writers' signatures and murals became more elaborate and a unique style developed as a factor of the aerosol medium and the speed required for illicit work. Many now recognize graffiti and street art as a unique art form and specifically manufactured aerosol paints are made for the graffiti artist. A stencil protects a surface, except the specific shape to be painted. Stencils can be purchased as movable letters, ordered as professionally cut logos or hand-cut by artists.

Tempera

Tempera, also known as egg tempera, is a permanent, fast-drying painting medium consisting of colored pigment mixed with a water-soluble binder medium (usually a glutinous material such as egg yolk or some other size). Tempera also refers to the paintings done in this medium. Tempera paintings are very long-lasting, and examples from the first centuries CE still exist. Egg tempera was a primary method of painting until after 1500 when it was superseded by the invention of oil painting. A paint commonly called tempera (though it is not) consisting of pigment and glue size is commonly used and referred to by some manufacturers in America as poster paint.

Water miscible oil paint

Water miscible oil paints (also called "water soluble" or "water-mixable") is a modern variety of oil paint engineered to be thinned and cleaned up with water, rather than having to use chemicals such as turpentine. It can be mixed and applied using the same techniques as traditional oil-based paint, but while still wet it can be effectively removed from brushes, palettes, and rags with ordinary soap and water. Its water solubility comes from the use of an oil medium in which one end of the molecule has been altered to bind loosely to water molecules, as in a solution.

Digital painting

Digital painting is a method of creating an art object (painting) digitally and/or a technique for making digital art on the computer. As a method of creating an art object, it adapts traditional painting medium such as acrylic paint, oils, ink, watercolor, etc. and applies the pigment to traditional carriers, such as woven canvas cloth, paper, polyester, etc. by means of computer software driving industrial robotic or office machinery (printers). As a technique, it refers to a computer graphics software program that uses a virtual canvas and virtual painting box of brushes, colors, and other supplies. The virtual box contains many instruments that do not exist outside the computer, and which give a digital artwork a different look and feel from an artwork that is made the traditional way. Furthermore, digital painting is not 'computer-generated' art as the computer does not automatically create images on the screen using some mathematical calculations. On the other hand, the artist uses his own painting technique to create a particular piece of work on the computer.

Painting styles

Style is used in two senses: It can refer to the distinctive visual elements, techniques, and methods that typify an individual artist's work. It can also refer to the movement or school that an artist is associated with. This can stem from an actual group that the artist was consciously involved with or it can be a category in which art historians have placed the painter. The word 'style' in the latter sense has fallen out of favor in academic discussions about contemporary painting, though it continues to be used in popular contexts. Such movements or classifications include the following:

Western

Modernism

Modernism describes both a set of cultural tendencies and an array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism. The term encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization, and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an emerging fully industrialized world. A salient characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness. This often led to experiments with form, and work that draws attention to the processes and materials used (and to the further tendency of abstraction).

Impressionism

The first example of modernism in painting was impressionism, a school of painting that initially focused on work done, not in studios, but outdoors (en plein air). Impressionist paintings demonstrated that human beings do not see objects, but instead see light itself. The school gathered adherents despite internal divisions among its leading practitioners and became increasingly influential. Initially rejected from the most important commercial show of the time, the government-sponsored Paris Salon, the Impressionists organized yearly group exhibitions in commercial venues during the 1870s and 1880s, timing them to coincide with the official Salon. A significant event of 1863 was the Salon des Refusés, created by Emperor Napoleon III to display all of the paintings rejected by the Paris Salon.

Abstract styles

Abstract painting uses a visual language of form, colour and line to create a composition that may exist with a degree of independence from visual references in the world. Abstract expressionism was an American post-World War II art movement that combined the emotional intensity and self-denial of the German Expressionists with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools—such as Futurism, Bauhaus and Cubism, and the image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic and, some feel, nihilistic.

Action painting, sometimes called gestural abstraction, is a style of painting in which paint is spontaneously dribbled, splashed or smeared onto the canvas, rather than being carefully applied. The resulting work often emphasizes the physical act of painting itself as an essential aspect of the finished work or concern of its artist. The style was widespread from the 1940s until the early 1960s, and is closely associated with abstract expressionism (some critics have used the terms "action painting" and "abstract expressionism" interchangeably).

Other modernist styles include:

Outsider art

The term outsider art was coined by art critic Roger Cardinal in 1972 as an English synonym for art brut (French: [aʁ bʁyt], "raw art" or "rough art"), a label created by French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art created outside the boundaries of official culture; Dubuffet focused particularly on art by insane-asylum inmates. Outsider art has emerged as a successful art marketing category (an annual Outsider Art Fair has taken place in New York since 1992). The term is sometimes misapplied as a catch-all marketing label for art created by people outside the mainstream "art world," regardless of their circumstances or the content of their work.

Photorealism

Photorealism is the genre of painting based on using the camera and photographs to gather information and then from this information, creating a painting that appears to be very realistic like a photograph. The term is primarily applied to paintings from the United States art movement that began in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As a full-fledged art movement, Photorealism evolved from Pop Art and as a counter to Abstract Expressionism.

Hyperrealism is a genre of painting and sculpture resembling a high-resolution photograph. Hyperrealism is a fully-fledged school of art and can be considered an advancement of Photorealism by the methods used to create the resulting paintings or sculptures. The term is primarily applied to an independent art movement and art style in the United States and Europe that has developed since the early 2000s.

Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that began in the early 1920s, and is best known for the artistic and literary production of those affiliated with the Surrealist Movement. Surrealist artworks feature the element of surprise, the uncanny, the unconscious, unexpected juxtapositions and non-sequitur; however, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost, with the works being an artifact. Leader André Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement.

Surrealism developed out of the Dada activities of World War I and the most important center of the movement was Paris. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, eventually affecting the visual arts, literature, film and music of many countries, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy and social theory.

East Asian

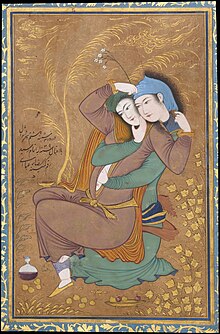

Islamic

Indian

- Oriya school

- Bengal school

- Kangra

- Madhubani

- Mysore

- Rajput

- Mughal

- Samikshavad

- Tanjore

- Warli

- Kerala mural painting

African

Contemporary art

1950s |

1960s |

1980s |

1990s |

2000s |

Types of painting

Allegory

Allegory is a figurative mode of representation conveying meaning other than the literal. Allegory communicates its message by means of symbolic figures, actions, or symbolic representation. Allegory is generally treated as a figure of rhetoric, but an allegory does not have to be expressed in language: it may be addressed to the eye and is often found in realistic painting. An example of a simple visual allegory is the image of the grim reaper. Viewers understand that the image of the grim reaper is a symbolic representation of death.

Bodegón

In Spanish art, a bodegón is a still life painting depicting pantry items, such as victuals, game, and drink, often arranged on a simple stone slab, and also a painting with one or more figures, but significant still life elements, typically set in a kitchen or tavern. Starting in the Baroque period, such paintings became popular in Spain in the second quarter of the 17th century. The tradition of still life painting appears to have started and was far more popular in the contemporary Low Countries, today Belgium and Netherlands (then Flemish and Dutch artists), than it ever was in southern Europe. Northern still lifes had many subgenres: the breakfast piece was augmented by the trompe-l'œil, the flower bouquet, and the vanitas. In Spain, there were much fewer patrons for this sort of thing, but a type of breakfast piece did become popular, featuring a few objects of food and tableware laid on a table.

Figure painting

A figure painting is a work of art in any of the painting media with the primary subject being the human figure, whether clothed or nude. Figure painting may also refer to the activity of creating such a work. The human figure has been one of the contrast subjects of art since the first Stone Age cave paintings, and has been reinterpreted in various styles throughout history. Some artists well known for figure painting are Peter Paul Rubens, Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet.

Illustration painting

Illustration paintings are those used as illustrations in books, magazines, and theater or movie posters and comic books. Today, there is a growing interest in collecting and admiring the original artwork. Various museum exhibitions, magazines, and art galleries have devoted space to the illustrators of the past. In the visual art world, illustrators have sometimes been considered less important in comparison with fine artists and graphic designers. But as the result of computer game and comic industry growth, illustrations are becoming valued as popular and profitable artworks that can acquire a wider market than the other two, especially in Korea, Japan, Hong Kong and the United States.

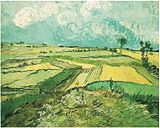

Landscape painting

Landscape painting is a term that covers the depiction of natural scenery such as mountains, valleys, trees, rivers, and forests, and especially art where the main subject is a wide view, with its elements arranged into a coherent composition. In other works landscape backgrounds for figures can still form an important part of the work. The sky is almost always included in the view, and weather is often an element of the composition. Detailed landscapes as a distinct subject are not found in all artistic traditions and develop when there is already a sophisticated tradition of representing other subjects. The two main traditions spring from Western painting and Chinese art, going back well over a thousand years in both cases.

Portrait painting

Portrait paintings are representations of a person, in which the face and its expression is predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. The art of the portrait flourished in Ancient Greek and especially Roman sculpture, where sitters demanded individualized and realistic portraits, even unflattering ones. One of the best-known portraits in the Western world is Leonardo da Vinci's painting titled Mona Lisa, which is thought to be a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo.

Still life

A still life is a work of art depicting mostly inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects—which may be either natural (food, flowers, plants, rocks, or shells) or man-made (drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, coins, pipes, and so on). With origins in the Middle Ages and Ancient Greek/Roman art, still life paintings give the artist more leeway in the arrangement of design elements within a composition than do paintings of other types of subjects such as landscape or portraiture. Still life paintings, particularly before 1700, often contained religious and allegorical symbolism relating to the objects depicted. Some modern still life breaks the two-dimensional barrier and employs three-dimensional mixed media, and uses found objects, photography, computer graphics, as well as video and sound.