Universal basic income (UBI), also called unconditional basic income, citizen's basic income, basic income guarantee, basic living stipend, guaranteed annual income, universal income security program or universal demogrant, is a sociopolitical financial transfer concept in which all citizens of a given population regularly receive a legally stipulated and equal financial grant paid by the government without a means test. A basic income can be implemented nationally, regionally, or locally. If the level is sufficient to meet a person's basic needs (i.e., at or above the poverty line), it is sometimes called a full basic income; if it is less than that amount, it may be called a partial basic income.

There are several welfare arrangements that can be viewed as related to basic income. Many countries have something like a basic income for children. Pension may be partly similar to basic income. There are also quasi-basic income systems, like Bolsa Familia in Brazil, which is conditional and concentrated on the poor, or the Thamarat Program in Sudan, which was introduced by the transitional government to ease the effects of the economic crisis inherited from the Bashir regime. The Alaska Permanent Fund is essentially a partial basic income, which averages $1,600 annually per resident (in 2019 currency). The negative income tax (NIT) can be viewed as a basic income in which citizens receive less and less money until this effect is reversed the more a person earns.

Several political discussions are related to the basic income debate, including those regarding automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and the future of the necessity of work. A key issue in these debates is whether automation and AI will significantly reduce the number of available jobs and whether a basic income could help prevent or alleviate such problems by allowing everyone to benefit from a society's wealth, as well as whether a UBI could be a stepping stone to a resource-based or post-scarcity economy. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted some countries to send direct payments to citizens.

History

Antiquity

In an early example, Trajan, emperor of Rome from 98–117 AD, personally gave 650 denarii (equivalent to perhaps US$260 in 2002) to all common Roman citizens who applied.

16th to 18th century

In his Utopia (1516), English statesman and philosopher Sir Thomas More depicts a society in which every person receives a guaranteed income. Spanish scholar Johannes Ludovicus Vives (1492–1540) proposed that the municipal government should be responsible for securing a subsistence minimum to all its residents "not on the grounds of justice but for the sake of a more effective exercise of morally required charity." Vives also argued that to qualify for poor relief, the recipient must "deserve the help he or she gets by proving his or her willingness to work." In the late 18th century, English Radical Thomas Spence and English-born American philosopher Thomas Paine both had ideas in the same direction.

Paine authored Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), the two most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution. He is also the author of Agrarian Justice, published in 1797. In it, he proposed concrete reforms to abolish poverty. In particular, he proposed a universal social insurance system comprising old-age pensions and disability support and universal stakeholder grants for young adults, funded by a 10% inheritance tax focused on land.

Early 20th century

Around 1920, support for basic income started growing, primarily in England.

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) argued for a new social model that combined the advantages of socialism and anarchism, and that basic income should be a vital component in that new society.

Dennis and Mabel Milner, a Quaker married couple of the Labour Party, published a short pamphlet entitled "Scheme for a State Bonus" (1918) that argued for the "introduction of an income paid unconditionally on a weekly basis to all citizens of the United Kingdom." They considered it a moral right for everyone to have the means to subsistence, and thus it should not be conditional on work or willingness to work.

C. H. Douglas was an engineer who became concerned that most British citizens could not afford to buy the goods that were produced, despite the rising productivity in British industry. His solution to this paradox was a new social system he called social credit, a combination of monetary reform and basic income.

In 1944 and 1945, the Beveridge Committee, led by the British economist William Beveridge, developed a proposal for a comprehensive new welfare system of social insurance, means-tested benefits, and unconditional allowances for children. Committee member Lady Rhys-Williams argued that the incomes for adults should be more like a basic income. She was also the first to develop the negative income tax model. Her son Brandon Rhys Williams proposed a basic income to a parliamentary committee in 1982, and soon after that in 1984, the Basic Income Research Group, now the Citizen's Basic Income Trust, began to conduct and disseminate research on basic income.

Late 20th century

In his 1964 State of the Union address, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced legislation to fight the "war on poverty". Johnson believed in expanding the federal government's roles in education and health care as poverty reduction strategies. In this political climate the idea of a guaranteed income for every American also took root. Notably, a document, signed by 1200 economists, called for a guaranteed income for every American. Six ambitious basic income experiments started up on the related concept of negative income tax. Succeeding President Richard Nixon explained its purpose as "to provide both a safety net for the poor and a financial incentive for welfare recipients to work." Congress eventually approved a guaranteed minimum income for the elderly and the disabled.

In the mid-1970s the main competitor to basic income and negative income tax, the Earned income tax credit (EITC), or its advocates, won over enough legislators for the US Congress to pass laws on that policy. In 1986, the Basic Income European Network, later renamed to Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), was founded, with academic conferences every second year. Other advocates included the green political movement, as well as activists and some groups of unemployed people.

In the latter part of the 20th century, discussions were held around automatization and jobless growth, the possibility of combining economic growth with ecological sustainable development, and how to reform the welfare state bureaucracy. Basic income was interwoven in these and many other debates. During the BIEN academic conferences there were papers about basic income from a wide variety of perspectives, including economics, sociology, and human right approaches.

21st century

In recent years the idea has come to the forefront more than before. The Swiss referendum about basic income in Switzerland 2016 was covered in media worldwide, despite its rejection. Famous business people like Elon Musk and Andrew Yang have lent their support, as have high-profile politicians like Jeremy Corbyn.

In the US Democratic Party primaries, a newcomer, Andrew Yang, touted basic income as his core policy. His policy, referred to as a "Freedom Dividend", would have provided American citizens US$1000 a month.

Response to COVID-19

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic impact, basic income and similar proposals such as helicopter money and cash transfers were increasingly discussed across the world. Most countries have implemented forms of partial unemployment schemes, which effectively subsidized workers' incomes without work requirement. Some countries like the United States, Spain, Hong Kong and Japan introduced direct cash transfers to citizens.

In Europe, a petition calling for an "emergency basic income" gathered more than 200,000 signatures, and polls suggested widespread support in public opinion for it. Unlike the various stimulus packages of the US administration, the EU's stimulus plans did not include any form of income-support policies.

Basic income vs negative income tax

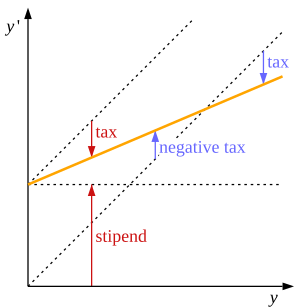

The diagram shows a basic income/negative tax system combined with flat income tax (the same percentage in tax for every income level).

Y is here the pre-tax salary given by the employer and y' is the net income.

Negative income tax

For low earnings there is no income tax in the negative income tax system. They receive money, in the form of a negative income tax, but they don't pay any tax. Then, as their labour income increases, this benefit, this money from the state, gradually decreases. That decrease is to be seen as a mechanism for the poor, instead of the poor paying tax.

Basic income

That is however not the case in the corresponding basic income system in the diagram. There everyone typically pays income taxes. But on the other hand everyone also gets the same amount in basic income.

But the net income is the same

But, as the orange line in the diagram shows, the net income is anyway the same. No matter how much or how little one earns, the amount of money one gets in one's pocket is the same, regardless of which of these two systems is used.

Basic income and negative income tax are generally seen to be similar in economic net effects, but there are some differences:

- Psychological. Philip Harvey accepts that "both systems would have the same redistributive effect and tax earned income at the same marginal rate" but does not agree that "the two systems would be perceived by taxpayers as costing the same".

- Tax profile. Tony Atkinson made a distinction based on whether the tax profile was flat (for basic income) or variable (for NIT).

- Timing. Philippe Van Parijs states that "the economic equivalence between the two programs should not hide that the fact that they have different effects on recipients because of the different timing of payments: ex-ante in Basic Income, ex-post in Negative Income Tax".

Perspectives and arguments

Basic income and automation

There is a prevailing opinion that we are in an era of technological unemployment – that technology is increasingly making skilled workers obsolete.

Prof. Mark MacCarthy (2014)

One central rationale for basic income is the belief that automation and robotisation could lead to a world with fewer paid jobs. U.S. presidential candidate and nonprofit founder Andrew Yang has stated that automation caused the loss of 4 million manufacturing jobs and advocated for a UBI (which he calls a Freedom Dividend) of $1,000/month rather than worker retraining programs. Yang has stated that he is heavily influenced by Martin Ford. Ford, in his turn, believes that the emerging technologies will fail to deliver a lot of employment; on the contrary, because the new industries will "rarely, if ever, be highly labor-intensive". Similar ideas have been debated many times before in history—that "the machines will take the jobs"—so the argument is not new. But what is quite new is the existence of several academic studies that do indeed forecast a future with substantially less employment, in the decades to come. Additionally, President Barack Obama has stated that he believes that the growth of artificial intelligence will lead to increased discussion around the idea of "unconditional free money for everyone".

Basic income and economics

Some proponents of UBI have argued that basic income could increase economic growth because it would sustain people while they invest in education to get higher-skilled and well-paid jobs. However, there is also a discussion of basic income within the degrowth movement, which argues against economic growth.

The cost of basic income is one of the biggest questions in the public debate as well as in the research. But the cost depends on many things. It first and foremost depends on the level of the basic income as such, and it also depends on many technical points regarding exactly how it is constructed. According to Karl Widerquist it also depends heavily on what one means with the concept of "cost".

Basic income and work

Many critics of basic income argue that people in general will work less, which in turn means less tax revenue and less money for the state and local governments. Although it is difficult to know for sure what will happen if a whole country introduces basic income, there are nevertheless some studies who have attempted to look at this question.

- In negative income tax experiments in the United States in the 1970 there was a five percent decline in the hours worked. The work reduction was largest for second earners in two-earner households and weakest for primary earners. The reduction in hours was higher when the benefit was higher.

- In the Mincome experiment in rural Dauphin, Manitoba, also in the 1970s, there were slight reductions in hours worked during the experiment. However, the only two groups who worked significantly less were new mothers, and teenagers working to support their families. New mothers spent this time with their infant children, and working teenagers put significant additional time into their schooling.

- A study from 2017 showed no evidence that people worked less because of the Iranian subsidy reform (a basic income-reform).

Regarding the question of basic income vs jobs there is also the aspect of so-called welfare traps. Proponents of basic income often argue that with a basic income, unattractive jobs would necessarily have to be better paid and their working conditions improved, so that people still do them without need, reducing these traps.

Philosophy and morality

By definition, universal basic income does not make a distinction between "deserving" and "undeserving" individuals when making payments. Opponents argue that this lack of discrimination is unfair: "Those who genuinely choose idleness or unproductive activities cannot expect those who have committed to doing productive work to subsidize their livelihood. Responsibility is central to fairness." Proponents argue that this lack of discrimination is a way to reduce social stigma.

Basic income, health and poverty

The first comprehensive systematic review of the health impact of basic income (or rather unconditional cash transfers in general) in low- and middle-income countries, a study which included 21 studies of which 16 were randomized controlled trials, found a clinically meaningful reduction in the likelihood of being sick by an estimated 27%. Unconditional cash transfers, according to the study, may also improve food security and dietary diversity. Children in recipient families are also more likely to attend school and the cash transfers may increase money spent on health care.

The Canadian Medical Association passed a motion in 2015 in clear support of basic income and for basic income trials in Canada.

Academics on basic income

Economists

- James Meade advocated for a social dividend scheme funded by publicly owned productive assets.

- Bertrand Russell argued for a basic income alongside public ownership as a means of shortening the average working day and achieving full employment.

- Guy Standing has proposed financing a social dividend from a democratically accountable sovereign wealth fund built up primarily from the proceeds of a tax on rentier income derived from ownership or control of assets—physical, financial, and intellectual. Standing also generally argues that basic income would be a much simpler and more transparent welfare system.

- Douglas Rushkoff, a professor of Media Theory and Digital Economics at the City University of New York, has stated that he sees basic income as a sophisticated way for corporations to get richer at the expense of public money.

- Milton Friedman, world famous economist, supported UBI by reasoning that it would help to reduce poverty. He said: "The virtue of [a negative income tax] is precisely that it treats everyone the same way. [...] [T]here's none of this unfortunate discrimination among people."

- Eric Maskin has stated that "a minimum income makes sense, but not at the cost of eliminating Social Security and Medicare".

- Simeon Djankov, professor at the London School of Economics, argues the costs of a generous system are prohibitive.

- Ailsa McKay, a Scottish economist, has argued that basic income is a way to promote gender equality. She has specifically argued that "social policy reform should take account of all gender inequalities and not just those relating to the traditional labor market" and that "the citizens' basic income model can be a tool for promoting gender-neutral social citizenship rights".

Other academics

- Erik Olin Wright argues that basic income will empower labor by giving the workers greater bargaining power.

- Harry Shutt proposed basic income and other measures to make most or all businesses collective rather than private. These measures would create a post-capitalist economic system.

- Philippe Van Parijs, a Belgian philosopher, has argued that basic income at the highest sustainable level is needed to support real freedom, or the freedom to do whatever one "might want to do".

- Karl Widerquist and others have proposed a theory of freedom in which basic income is needed to protect the power to refuse work.

- Frances Fox Piven argues that an income guarantee would benefit all workers by liberating them from the anxiety that results from the "tyranny of wage slavery" and provide opportunities for people to pursue different occupations and develop untapped potentials for creativity.

- André Gorz, a French sociologist, saw basic income as a necessary adaptation to the increasing automation of work, yet basic income also enables workers to overcome alienation in work and life and to increase their amount of leisure time.

Pilot programs and experiments

Since the 1960s, but in particular since 2010, several pilot programs and experiments on basic income have been conducted. Some examples include:

1960s−1970s

- Experiments with negative income tax in United States and Canada in the 1960s and 1970s.

- The province of Manitoba, Canada experimented with Mincome, a basic guaranteed income, in the 1970s. In the town of Dauphin, Manitoba, labor only decreased by 13%, much less than expected.

2000−2009

- The basic income grant in Namibia, launched in 2008 and ended in 2009.

- An independent pilot implemented in São Paulo, Brazil launched in 2009.

2010−2019

- Basic income trials run in 2011-2012 in several villages in India, whose government has proposed a guaranteed basic income for all citizens. It was found that basic income in the region raised the education rate of young people by 25%.

- Iran introduced a national basic income program in autumn 2010. It is paid to all citizens and replaces the gasoline subsidies, electricity and some food products, that the country applied for years to reduce inequalities and poverty. The sum corresponded in 2012 to approximately US$40 per person per month, US$480 per year for a single person and US$2,300 for a family of five people.

- In Spain, the ingreso mínimo vital, the income guarantee system, is an economic benefit guaranteed by the social security in Spain, but in 2016 was considered in need of reform.

- The GiveDirectly experiment in a disadvantaged village of Nairobi, Kenya, the longest-running basic income pilot as of November 2017, which is set to run for 12 years.

- A project called Eight in a village in Fort Portal, Uganda, that a nonprofit organization launched in January 2017, which provides income for 56 adults and 88 children through mobile money.

- A two-year pilot the Finnish government began in January 2017 which involved 2,000 subjects. In April 2018, the Finnish government rejected a request for funds to extend and expand the program from Kela (Finland's social security agency).

- An experiment in the city of Utrecht in the Netherlands, launched in early 2017, that is testing different rates of aid.

- A three-year basic income pilot that the Ontario provincial government, Canada, launched in the cities of Hamilton, Thunder Bay and Lindsay in July 2017. Although called basic income, it was only made available to those with a low income and funding would be removed if they obtained employment, making it more related to the current welfare system than true basic income. The pilot project was canceled on 31 July 2018 by the newly elected Progressive Conservative government under Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

- In Israel, in 2018 a non-profit initiative GoodDollar started with an objective to build a global economic framework for providing universal, sustainable and scalable basic income through new digital asset technology of blockchain. The non-profit aims to launch a peer-to-peer money transfer network in which money can be distributed to those most in need, regardless of their location, based on the principles of UBI. The project raised US$1 million from eToro.

- The Rythu Bandhu scheme is a welfare scheme started in the state of Telangana, India, in May 2018, aimed at helping farmers. Each farm owner receives 4,000 INR per acre twice a year for rabi and kharif harvests. To finance the program a budget allocation of 120 billion INR (US$1.6 million as of June 2020) was made in the 2018–2019 state budget.

2020−present

- Swiss non-profit Social Income started paying out basic incomes in the form of mobile money in 2020 to people in need in Sierra Leone. Contributions finance the international initiative from people worldwide, who donate 1% of their monthly paychecks.

- In May 2020 Spain introduced minimum basic income, reaching about 2% of the population, in response to COVID-19 in order to "fight a spike in poverty due to the coronavirus pandemic". It is expected to cost state coffers three billion euros ($3.5 billion) a year."

- In August 2020, a project in Germany started that gives a 1,200 Euros monthly basic income in a lottery system to citizens who apply online. The crowdsourced project will last three years and be compared against 1,380 people who do not receive basic income.

- In October 2020, HudsonUP was launched in Hudson, New York, by The Spark of Hudson and Humanity Forward Foundation to give $500 monthly basic income to 25 residents. It will last five years and be compared against 50 people who are not receiving basic income.

- In May 2021 the government of Wales, which has devolved powers in matters of Social Welfare within the UK, announced the trialling of a universal basic income scheme to "see whether the promises that basic income holds out are genuinely delivered".

Examples of payments with similarities

Alaska Permanent Fund

The Permanent Fund of Alaska in the United States provides a kind of yearly basic income based on the oil and gas revenues of the state to nearly all state residents. More precisely the fund resembles a sovereign wealth fund, investing resource revenues into bonds, stocks, and other conservative investment options with the intent to generate renewable revenue for future generations. The fund has had a noticeable yet diminishing effect on reducing poverty among rural Alaska Indigenous people, notably in the elderly population. However, the payment is not high enough to cover basic expenses (it has never exceeded $2,100) and is not a fixed, guaranteed amount. For these reasons, it is not considered a basic income.

Macau

Macau's Wealth Partaking Scheme provides some annual basic income to permanent residents, funded by revenues from the city's casinos. However, the amount disbursed is not sufficient to cover basic living expenses, so it is not considered a basic income.

Bolsa Familia

Bolsa Família is a large social welfare program in Brazil that provides money to many low-income families in the country. The system is related to basic income, but has more conditions, like asking the recipients to keep their children in school until graduation. As of March 2020, the program covers 13.8 million families, and pays an average of $34 per month, in a country where the minimum wage is $190 per month.

Other similar welfare programs

- Pension: A payment which in some countries is guaranteed to all citizens above a certain age. The difference from true basic income is that it is restricted to people over a certain age.

- Child benefit: A program similar to pensions but restricted to parents of children, usually allocated based on the number of children.

- Conditional cash transfer: A regular payment given to families, but only to the poor. It is usually dependent on basic conditions such as sending their children to school or having them vaccinated. Programs include Bolsa Família in Brazil and Programa Prospera in Mexico.

- Guaranteed minimum income differs from a basic income in that it is restricted to those in search of work and possibly other restrictions, such as savings being below a certain level. Example programs are unemployment benefits in the UK, the revenu de solidarité active in France and citizens' income in Italy.

- Full and partial basic income: When the level of the basic income is high enough for people to live purely from that income, it is sometimes referred to as a "full basic income". If not, it is often referred to as a "partial basic income". No country has yet introduced either to all its citizens.

Petitions, polls and referenda

- 2008: An official petition for basic income was launched in Germany by Susanne Wiest. The petition was accepted, and Susanne Wiest was invited for a hearing at the German parliament's Commission of Petitions. After the hearing, the petition was closed as "unrealizable."

- 2013–2014: A European Citizens' Initiative collected 280,000 signatures demanding that the European Commission study the concept of an unconditional basic income.

- 2015: A citizen's initiative in Spain received 185,000 signatures, short of the required number to mandate that the Spanish parliament discuss the proposal.

- 2016: The world's first universal basic income referendum in Switzerland on 5 June 2016 was rejected with a 76.9% majority. Also in 2016, a poll showed that 58% of the EU's population is aware of basic income, and 65% would vote in favour of the idea.

- 2017: Politico/Morning Consult asked 1,994 Americans about their opinions on several political issues including national basic income; 43% either "strongly supported" or "somewhat supported" the idea.

- 2018: The results of a poll by Gallup conducted last year between September and October were published. 48% of respondents supported universal basic income.

- 2019: In November, an Austrian initiative received approximately 70,000 signatures but failed to reach the 100,000 signatures needed for a parliamentary discussion. The initiative was started by Peter Hofer. His proposal suggested a basic income of €1,200 for every Austrian citizen.

- 2020: A study by Oxford University found that 71% of Europeans are now in favour of basic income. The study was conducted in March, with 12,000 respondents and in 27 EU-member states and the UK. A YouGov-poll likewise found a majority for universal basic income in United Kingdom and a poll by University of Chicago found that 51% of Americans aged 18–36 support a monthly basic income of $1,000. In the UK there was also a letter, signed by over 170 MPs and Lords from multiple political parties, calling on the government to introduce a universal basic income during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 2020: A Pew Research Center Survey, conducted online in August 2020, of 11,000 U.S. adults found that a majority (54%) oppose the federal government providing a guaranteed income of $1,000 per month to all adults, while 45% support it.

- 2020: In a poll by Hill-HarrisX, 55% of Americans voted in favour of UBI in August, up from 49% in September 2019 and 43% in February 2019.

- 2020: The results of an online survey of 2,031 participants conducted in 2018 in Germany were published: 51% were either "very much in favor" or "in favor" of UBI being introduced.

- 2021: A Change.org petition calling for monthly stimulus checks in the amount of $2,000 per adult and $1,000 per child for the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic had received almost 3 million signatures.

See also

- Citizen's dividend

- Economic, social and cultural rights

- Equality of outcome

- Estovers – Allowance out of an estate

- FairTax § monthly tax rebate

- Geolibertarianism

- Global basic income

- Guaranteed minimum income

- Happiness economics

- Humanistic economics

- Involuntary unemployment

- Job guarantee

- Left-libertarianism

- Limitarianism (ethical)

- List of advocates of basic income

- List of basic income models

- Living wage

- Moral universalism

- New Cuban economy

- Old Age Security

- Post-work society

- Quatinga Velho

- Rationing

- Redistribution of income and wealth

- Social safety net

- Speenhamland system

- "The Triple Revolution"

- Universal basic services

- Universal Credit

- Universal value

- Universalism

- Wage subsidy

- Welfare capitalism

- Workfare

- Working time