In physics, a state of matter is one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist. Four states of matter are observable in everyday life: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. Many intermediate states are known to exist, such as liquid crystal, and some states only exist under extreme conditions, such as Bose–Einstein condensates, neutron-degenerate matter, and quark–gluon plasma, which only occur, respectively, in situations of extreme cold, extreme density, and extremely high energy. For a complete list of all exotic states of matter, see the list of states of matter.

Historically, the distinction is made based on qualitative differences in properties. Matter in the solid state maintains a fixed volume and shape, with component particles (atoms, molecules or ions) close together and fixed into place. Matter in the liquid state maintains a fixed volume, but has a variable shape that adapts to fit its container. Its particles are still close together but move freely. Matter in the gaseous state has both variable volume and shape, adapting both to fit its container. Its particles are neither close together nor fixed in place. Matter in the plasma state has variable volume and shape, and contains neutral atoms as well as a significant number of ions and electrons, both of which can move around freely.

The term phase is sometimes used as a synonym for state of matter, but a system can contain several immiscible phases of the same state of matter.

Four fundamental states

Solid

In a solid, constituent particles (ions, atoms, or molecules) are closely packed together. The forces between particles are so strong that the particles cannot move freely but can only vibrate. As a result, a solid has a stable, definite shape, and a definite volume. Solids can only change their shape by an outside force, as when broken or cut.

In crystalline solids, the particles (atoms, molecules, or ions) are packed in a regularly ordered, repeating pattern. There are various different crystal structures, and the same substance can have more than one structure (or solid phase). For example, iron has a body-centred cubic structure at temperatures below 912 °C (1,674 °F), and a face-centred cubic structure between 912 and 1,394 °C (2,541 °F). Ice has fifteen known crystal structures, or fifteen solid phases, which exist at various temperatures and pressures.

Glasses and other non-crystalline, amorphous solids without long-range order are not thermal equilibrium ground states; therefore they are described below as nonclassical states of matter.

Solids can be transformed into liquids by melting, and liquids can be transformed into solids by freezing. Solids can also change directly into gases through the process of sublimation, and gases can likewise change directly into solids through deposition.

Liquid

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. The volume is definite if the temperature and pressure are constant. When a solid is heated above its melting point, it becomes liquid, given that the pressure is higher than the triple point of the substance. Intermolecular (or interatomic or interionic) forces are still important, but the molecules have enough energy to move relative to each other and the structure is mobile. This means that the shape of a liquid is not definite but is determined by its container. The volume is usually greater than that of the corresponding solid, the best known exception being water, H2O. The highest temperature at which a given liquid can exist is its critical temperature.

Gas

A gas is a compressible fluid. Not only will a gas conform to the shape of its container but it will also expand to fill the container.

In a gas, the molecules have enough kinetic energy so that the effect of intermolecular forces is small (or zero for an ideal gas), and the typical distance between neighboring molecules is much greater than the molecular size. A gas has no definite shape or volume, but occupies the entire container in which it is confined. A liquid may be converted to a gas by heating at constant pressure to the boiling point, or else by reducing the pressure at constant temperature.

At temperatures below its critical temperature, a gas is also called a vapor, and can be liquefied by compression alone without cooling. A vapor can exist in equilibrium with a liquid (or solid), in which case the gas pressure equals the vapor pressure of the liquid (or solid).

A supercritical fluid (SCF) is a gas whose temperature and pressure are above the critical temperature and critical pressure respectively. In this state, the distinction between liquid and gas disappears. A supercritical fluid has the physical properties of a gas, but its high density confers solvent properties in some cases, which leads to useful applications. For example, supercritical carbon dioxide is used to extract caffeine in the manufacture of decaffeinated coffee.

Plasma

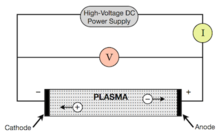

Like a gas, plasma does not have definite shape or volume. Unlike gases, plasmas are electrically conductive, produce magnetic fields and electric currents, and respond strongly to electromagnetic forces. Positively charged nuclei swim in a "sea" of freely-moving disassociated electrons, similar to the way such charges exist in conductive metal, where this electron "sea" allows matter in the plasma state to conduct electricity.

A gas is usually converted to a plasma in one of two ways, e.g., either from a huge voltage difference between two points, or by exposing it to extremely high temperatures. Heating matter to high temperatures causes electrons to leave the atoms, resulting in the presence of free electrons. This creates a so-called partially ionised plasma. At very high temperatures, such as those present in stars, it is assumed that essentially all electrons are "free", and that a very high-energy plasma is essentially bare nuclei swimming in a sea of electrons. This forms the so-called fully ionised plasma.

The plasma state is often misunderstood, and although not freely existing under normal conditions on Earth, it is quite commonly generated by either lightning, electric sparks, fluorescent lights, neon lights or in plasma televisions. The Sun's corona, some types of flame, and stars are all examples of illuminated matter in the plasma state.

Phase transitions

A state of matter is also characterized by phase transitions. A phase transition indicates a change in structure and can be recognized by an abrupt change in properties. A distinct state of matter can be defined as any set of states distinguished from any other set of states by a phase transition. Water can be said to have several distinct solid states. The appearance of superconductivity is associated with a phase transition, so there are superconductive states. Likewise, ferromagnetic states are demarcated by phase transitions and have distinctive properties. When the change of state occurs in stages the intermediate steps are called mesophases. Such phases have been exploited by the introduction of liquid crystal technology.

The state or phase of a given set of matter can change depending on pressure and temperature conditions, transitioning to other phases as these conditions change to favor their existence; for example, solid transitions to liquid with an increase in temperature. Near absolute zero, a substance exists as a solid. As heat is added to this substance it melts into a liquid at its melting point, boils into a gas at its boiling point, and if heated high enough would enter a plasma state in which the electrons are so energized that they leave their parent atoms.

Forms of matter that are not composed of molecules and are organized by different forces can also be considered different states of matter. Superfluids (like Fermionic condensate) and the quark–gluon plasma are examples.

In a chemical equation, the state of matter of the chemicals may be shown as (s) for solid, (l) for liquid, and (g) for gas. An aqueous solution is denoted (aq). Matter in the plasma state is seldom used (if at all) in chemical equations, so there is no standard symbol to denote it. In the rare equations that plasma is used it is symbolized as (p).

Non-classical states

Glass

Glass is a non-crystalline or amorphous solid material that exhibits a glass transition when heated towards the liquid state. Glasses can be made of quite different classes of materials: inorganic networks (such as window glass, made of silicate plus additives), metallic alloys, ionic melts, aqueous solutions, molecular liquids, and polymers. Thermodynamically, a glass is in a metastable state with respect to its crystalline counterpart. The conversion rate, however, is practically zero.

Crystals with some degree of disorder

A plastic crystal is a molecular solid with long-range positional order but with constituent molecules retaining rotational freedom; in an orientational glass this degree of freedom is frozen in a quenched disordered state.

Similarly, in a spin glass magnetic disorder is frozen.

Liquid crystal states

Liquid crystal states have properties intermediate between mobile liquids and ordered solids. Generally, they are able to flow like a liquid, but exhibiting long-range order. For example, the nematic phase consists of long rod-like molecules such as para-azoxyanisole, which is nematic in the temperature range 118–136 °C (244–277 °F). In this state the molecules flow as in a liquid, but they all point in the same direction (within each domain) and cannot rotate freely. Like a crystalline solid, but unlike a liquid, liquid crystals react to polarized light.

Other types of liquid crystals are described in the main article on these states. Several types have technological importance, for example, in liquid crystal displays.

Magnetically ordered

Transition metal atoms often have magnetic moments due to the net spin of electrons that remain unpaired and do not form chemical bonds. In some solids the magnetic moments on different atoms are ordered and can form a ferromagnet, an antiferromagnet or a ferrimagnet.

In a ferromagnet—for instance, solid iron—the magnetic moment on each atom is aligned in the same direction (within a magnetic domain). If the domains are also aligned, the solid is a permanent magnet, which is magnetic even in the absence of an external magnetic field. The magnetization disappears when the magnet is heated to the Curie point, which for iron is 768 °C (1,414 °F).

An antiferromagnet has two networks of equal and opposite magnetic moments, which cancel each other out so that the net magnetization is zero. For example, in nickel(II) oxide (NiO), half the nickel atoms have moments aligned in one direction and half in the opposite direction.

In a ferrimagnet, the two networks of magnetic moments are opposite but unequal, so that cancellation is incomplete and there is a non-zero net magnetization. An example is magnetite (Fe3O4), which contains Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions with different magnetic moments.

A quantum spin liquid (QSL) is a disordered state in a system of interacting quantum spins which preserves its disorder to very low temperatures, unlike other disordered states. It is not a liquid in physical sense, but a solid whose magnetic order is inherently disordered. The name "liquid" is due to an analogy with the molecular disorder in a conventional liquid. A QSL is neither a ferromagnet, where magnetic domains are parallel, nor an antiferromagnet, where the magnetic domains are antiparallel; instead, the magnetic domains are randomly oriented. This can be realized e.g. by geometrically frustrated magnetic moments that cannot point uniformly parallel or antiparallel. When cooling down and settling to a state, the domain must "choose" an orientation, but if the possible states are similar in energy, one will be chosen randomly. Consequently, despite strong short-range order, there is no long-range magnetic order.

Microphase-separated

Copolymers can undergo microphase separation to form a diverse array of periodic nanostructures, as shown in the example of the styrene-butadiene-styrene block copolymer shown at right. Microphase separation can be understood by analogy to the phase separation between oil and water. Due to chemical incompatibility between the blocks, block copolymers undergo a similar phase separation. However, because the blocks are covalently bonded to each other, they cannot demix macroscopically as water and oil can, and so instead the blocks form nanometre-sized structures. Depending on the relative lengths of each block and the overall block topology of the polymer, many morphologies can be obtained, each its own phase of matter.

Ionic liquids also display microphase separation. The anion and cation are not necessarily compatible and would demix otherwise, but electric charge attraction prevents them from separating. Their anions and cations appear to diffuse within compartmentalized layers or micelles instead of freely as in a uniform liquid.

Low-temperature states

Superconductor

Superconductors are materials which have zero electrical resistivity, and therefore perfect conductivity. This is a distinct physical state which exists at low temperature, and the resistivity increases discontinuously to a finite value at a sharply-defined transition temperature for each superconductor.

A superconductor also excludes all magnetic fields from its interior, a phenomenon known as the Meissner effect or perfect diamagnetism. Superconducting magnets are used as electromagnets in magnetic resonance imaging machines.

The phenomenon of superconductivity was discovered in 1911, and for 75 years was only known in some metals and metallic alloys at temperatures below 30 K. In 1986 so-called high-temperature superconductivity was discovered in certain ceramic oxides, and has now been observed in temperatures as high as 164 K.

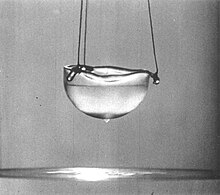

Superfluid

Close to absolute zero, some liquids form a second liquid state described as superfluid because it has zero viscosity (or infinite fluidity; i.e., flowing without friction). This was discovered in 1937 for helium, which forms a superfluid below the lambda temperature of 2.17 K (−270.98 °C; −455.76 °F). In this state it will attempt to "climb" out of its container. It also has infinite thermal conductivity so that no temperature gradient can form in a superfluid. Placing a superfluid in a spinning container will result in quantized vortices.

These properties are explained by the theory that the common isotope helium-4 forms a Bose–Einstein condensate (see next section) in the superfluid state. More recently, Fermionic condensate superfluids have been formed at even lower temperatures by the rare isotope helium-3 and by lithium-6.

Bose–Einstein condensate

In 1924, Albert Einstein and Satyendra Nath Bose predicted the "Bose–Einstein condensate" (BEC), sometimes referred to as the fifth state of matter. In a BEC, matter stops behaving as independent particles, and collapses into a single quantum state that can be described with a single, uniform wavefunction.

In the gas phase, the Bose–Einstein condensate remained an unverified theoretical prediction for many years. In 1995, the research groups of Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman, of JILA at the University of Colorado at Boulder, produced the first such condensate experimentally. A Bose–Einstein condensate is "colder" than a solid. It may occur when atoms have very similar (or the same) quantum levels, at temperatures very close to absolute zero, −273.15 °C (−459.67 °F).

Fermionic condensate

A fermionic condensate is similar to the Bose–Einstein condensate but composed of fermions. The Pauli exclusion principle prevents fermions from entering the same quantum state, but a pair of fermions can behave as a boson, and multiple such pairs can then enter the same quantum state without restriction.

Rydberg molecule

One of the metastable states of strongly non-ideal plasma are condensates of excited atoms. These atoms can also turn into ions and electrons if they reach a certain temperature. In April 2009, Nature reported the creation of Rydberg molecules from a Rydberg atom and a ground state atom, confirming that such a state of matter could exist. The experiment was performed using ultracold rubidium atoms.

Quantum Hall state

A quantum Hall state gives rise to quantized Hall voltage measured in the direction perpendicular to the current flow. A quantum spin Hall state is a theoretical phase that may pave the way for the development of electronic devices that dissipate less energy and generate less heat. This is a derivation of the Quantum Hall state of matter.

Photonic matter

Photonic matter is a phenomenon where photons interacting with a gas develop apparent mass, and can interact with each other, even forming photonic "molecules". The source of mass is the gas, which is massive. This is in contrast to photons moving in empty space, which have no rest mass, and cannot interact.

Dropleton

A "quantum fog" of electrons and holes that flow around each other and even ripple like a liquid, rather than existing as discrete pairs.

High-energy states

Degenerate matter

Under extremely high pressure, as in the cores of dead stars, ordinary matter undergoes a transition to a series of exotic states of matter collectively known as degenerate matter, which are supported mainly by quantum mechanical effects. In physics, "degenerate" refers to two states that have the same energy and are thus interchangeable. Degenerate matter is supported by the Pauli exclusion principle, which prevents two fermionic particles from occupying the same quantum state. Unlike regular plasma, degenerate plasma expands little when heated, because there are simply no momentum states left. Consequently, degenerate stars collapse into very high densities. More massive degenerate stars are smaller, because the gravitational force increases, but pressure does not increase proportionally.

Electron-degenerate matter is found inside white dwarf stars. Electrons remain bound to atoms but are able to transfer to adjacent atoms. Neutron-degenerate matter is found in neutron stars. Vast gravitational pressure compresses atoms so strongly that the electrons are forced to combine with protons via inverse beta-decay, resulting in a superdense conglomeration of neutrons. Normally free neutrons outside an atomic nucleus will decay with a half life of approximately 10 minutes, but in a neutron star, the decay is overtaken by inverse decay. Cold degenerate matter is also present in planets such as Jupiter and in the even more massive brown dwarfs, which are expected to have a core with metallic hydrogen. Because of the degeneracy, more massive brown dwarfs are not significantly larger. In metals, the electrons can be modeled as a degenerate gas moving in a lattice of non-degenerate positive ions.

Quark matter

In regular cold matter, quarks, fundamental particles of nuclear matter, are confined by the strong force into hadrons that consist of 2–4 quarks, such as protons and neutrons. Quark matter or quantum chromodynamical (QCD) matter is a group of phases where the strong force is overcome and quarks are deconfined and free to move. Quark matter phases occur at extremely high densities or temperatures, and there are no known ways to produce them in equilibrium in the laboratory; in ordinary conditions, any quark matter formed immediately undergoes radioactive decay.

Strange matter is a type of quark matter that is suspected to exist inside some neutron stars close to the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit (approximately 2–3 solar masses), although there is no direct evidence of its existence. In strange matter, part of the energy available manifests as strange quarks, a heavier analogue of the common down quark. It may be stable at lower energy states once formed, although this is not known.

Quark–gluon plasma is a very high-temperature phase in which quarks become free and able to move independently, rather than being perpetually bound into particles, in a sea of gluons, subatomic particles that transmit the strong force that binds quarks together. This is analogous to the liberation of electrons from atoms in a plasma. This state is briefly attainable in extremely high-energy heavy ion collisions in particle accelerators, and allows scientists to observe the properties of individual quarks, and not just theorize. Quark–gluon plasma was discovered at CERN in 2000. Unlike plasma, which flows like a gas, interactions within QGP are strong and it flows like a liquid.

At high densities but relatively low temperatures, quarks are theorized to form a quark liquid whose nature is presently unknown. It forms a distinct color-flavor locked (CFL) phase at even higher densities. This phase is superconductive for color charge. These phases may occur in neutron stars but they are presently theoretical.

Color-glass condensate

Color-glass condensate is a type of matter theorized to exist in atomic nuclei traveling near the speed of light. According to Einstein's theory of relativity, a high-energy nucleus appears length contracted, or compressed, along its direction of motion. As a result, the gluons inside the nucleus appear to a stationary observer as a "gluonic wall" traveling near the speed of light. At very high energies, the density of the gluons in this wall is seen to increase greatly. Unlike the quark–gluon plasma produced in the collision of such walls, the color-glass condensate describes the walls themselves, and is an intrinsic property of the particles that can only be observed under high-energy conditions such as those at RHIC and possibly at the Large Hadron Collider as well.

Very high energy states

Various theories predict new states of matter at very high energies. An unknown state has created the baryon asymmetry in the universe, but little is known about it. In string theory, a Hagedorn temperature is predicted for superstrings at about 1030 K, where superstrings are copiously produced. At Planck temperature (1032 K), gravity becomes a significant force between individual particles. No current theory can describe these states and they cannot be produced with any foreseeable experiment. However, these states are important in cosmology because the universe may have passed through these states in the Big Bang.

The gravitational singularity predicted by general relativity to exist at the center of a black hole is not a phase of matter; it is not a material object at all (although the mass-energy of matter contributed to its creation) but rather a property of spacetime. Because spacetime breaks down there, the singularity should not be thought of as a localized structure, but as a global, topological feature of spacetime. It has been argued that elementary particles are fundamentally not material, either, but are localized properties of spacetime. In quantum gravity, singularities may in fact mark transitions to a new phase of matter.

Other proposed states

Supersolid

A supersolid is a spatially ordered material (that is, a solid or crystal) with superfluid properties. Similar to a superfluid, a supersolid is able to move without friction but retains a rigid shape. Although a supersolid is a solid, it exhibits so many characteristic properties different from other solids that many argue it is another state of matter.

String-net liquid

In a string-net liquid, atoms have apparently unstable arrangement, like a liquid, but are still consistent in overall pattern, like a solid. When in a normal solid state, the atoms of matter align themselves in a grid pattern, so that the spin of any electron is the opposite of the spin of all electrons touching it. But in a string-net liquid, atoms are arranged in some pattern that requires some electrons to have neighbors with the same spin. This gives rise to curious properties, as well as supporting some unusual proposals about the fundamental conditions of the universe itself.

Superglass

A superglass is a phase of matter characterized, at the same time, by superfluidity and a frozen amorphous structure.

Arbitrary definition

Although multiple attempts have been made to create a unified account, ultimately the definitions of what states of matter exist and the point at which states change are arbitrary. Some authors have suggested that states of matter are better thought of as a spectrum between a solid and plasma instead of being rigidly defined.