From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Anorexia nervosa |

|---|

| Other names | Anorexia |

|---|

|

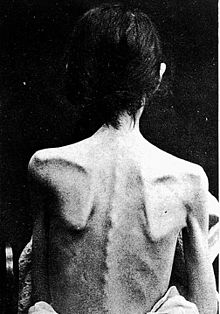

"Miss

A—" depicted in 1866 and in 1870 after treatment. She was one of the

earliest case studies of anorexia. From the published medical papers of Sir William Gull.

|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, Clinical psychology |

|---|

| Symptoms | Low weight, fear of gaining weight, strong desire to be thin, food restrictions body image disturbance |

|---|

| Complications | Osteoporosis, infertility, heart damage, suicide |

|---|

| Usual onset | Teen years to young adulthood |

|---|

| Causes | Unknown |

|---|

| Risk factors | Family history, high-level athletics, modelling, substance use disorder, dancing |

|---|

| Differential diagnosis | Body dysmorphic disorder, bulimia nervosa, hyperthyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, dysphagia, cancer |

|---|

| Treatment | Cognitive behavioral therapy, hospitalisation to restore weight |

|---|

| Prognosis | 5% risk of death over 10 years |

|---|

| Frequency | 2.9 million (2015) |

|---|

| Deaths | 600 (2015)

|

|---|

Anorexia nervosa, often referred to simply as anorexia, is an eating disorder characterized by low weight, food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin. Anorexia is a term of Greek origin: an- (ἀν-, prefix denoting negation) and orexis (ὄρεξις, "appetite"), translating literally to "a loss of appetite"; the adjective nervosa indicating the functional and non-organic nature of the disorder. Anorexia nervosa

was coined by Gull in 1873 but, despite literal translation, the

symptom of hunger is frequently present and the pathological control of

this instinct is a source of satisfaction for the patients.

Individuals with anorexia nervosa commonly see themselves as overweight, although they are in fact underweight. The DSM-5 describes this perceptual symptom as "disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced". In research and clinical settings, this symptom is called "body image disturbance". Individuals with anorexia nervosa also often deny that they have a problem with low weight. They may weigh themselves frequently, eat small amounts, and only eat certain foods. Some exercise excessively, force themselves to vomit (in the "anorexia purging" subtype), or use laxatives to lose weight and control body shapes. Medical complications may include osteoporosis, infertility, and heart damage, among others. Women will often stop having menstrual periods.

In extreme cases, patients with anorexia nervosa who continually refuse

significant dietary intake and weight restoration interventions, and

are declared incompetent to make decisions by a psychiatrist, may be fed

by force under restraint via nasogastric tube after asking their parents or proxies to make the decision for them.

The cause of anorexia is currently unknown. There appear to be some genetic components with identical twins more often affected than fraternal twins. Cultural factors also appear to play a role, with societies that value thinness having higher rates of the disease.

Additionally, it occurs more commonly among those involved in

activities that value thinness, such as high-level athletics, modeling,

and dancing. Anorexia often begins following a major life-change or stress-inducing event. The diagnosis requires a significantly low weight and the severity of disease is based on body mass index

(BMI) in adults with mild disease having a BMI of greater than 17,

moderate a BMI of 16 to 17, severe a BMI of 15 to 16, and extreme a BMI

less than 15. In children, a BMI for age percentile of less than the 5th percentile is often used.

Treatment of anorexia involves restoring the patient back to a

healthy weight, treating their underlying psychological problems, and

addressing behaviors that promote the problem. While medications do not help with weight gain, they may be used to help with associated anxiety or depression. Different therapy methods may be useful, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or an approach where parents assume responsibility for feeding their child, known as Maudsley family therapy. Sometimes people require admission to a hospital to restore weight. Evidence for benefit from nasogastric tube feeding is unclear;

such an intervention may be highly distressing for both anorexia

patients and healthcare staff when administered against the patient's

will under restraint. Some people with anorexia will have a single episode and recover while others may have recurring episodes over years. Many complications improve or resolve with the regaining of weight.

Globally, anorexia is estimated to affect 2.9 million people as of 2015. It is estimated to occur in 0.9% to 4.3% of women and 0.2% to 0.3% of men in Western countries at some point in their life.

About 0.4% of young women are affected in a given year and it is

estimated to occur ten times more commonly among women than men. Rates in most of the developing world are unclear. Often it begins during the teen years or young adulthood.

While anorexia became more commonly diagnosed during the 20th century

it is unclear if this was due to an increase in its frequency or simply

better diagnosis. In 2013, it directly resulted in about 600 deaths globally, up from 400 deaths in 1990. Eating disorders also increase a person's risk of death from a wide range of other causes, including suicide. About 5% of people with anorexia die from complications over a ten-year period, a nearly six times increased risk. The term "anorexia nervosa" was first used in 1873 by William Gull to describe this condition.

In recent years, evolutionary psychiatry as an emerging scientific discipline has been studying mental disorders

from an evolutionary perspective. It is still debated whether eating

disorders such as anorexia have evolutionary functions or if they are

problems resulting from a modern lifestyle.

Signs and symptoms

The back of a person with anorexia

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by attempts to lose weight to the point of starvation.

A person with anorexia nervosa may exhibit a number of signs and

symptoms, the type and severity of which may vary and be present but not

readily apparent.

Anorexia nervosa, and the associated malnutrition that results from self-imposed starvation, can cause complications in every major organ system in the body. Hypokalaemia, a drop in the level of potassium in the blood, is a sign of anorexia nervosa. A significant drop in potassium can cause abnormal heart rhythms, constipation, fatigue, muscle damage, and paralysis.

Signs and symptoms may be classified in physical, cognitive, affective, behavioral and perceptual:

Physical symptoms

Cognitive symptoms

- An obsession with counting calories and monitoring fat contents of food.

- Preoccupation with food, recipes, or cooking; may cook elaborate

dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves or consume a very

small portion.

- Admiration of thinner people.

- Thoughts of being fat or not thin enough

- An altered mental representation of one's body

- Difficulty in abstract thinking and problem solving

- Rigid and inflexible thinking

- Poor self-esteem

- Hypercriticism and clinical perfectionism

Affective symptoms

Behavioral symptoms

- Food restrictions despite being underweight or at a healthy weight.

- Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces, refusing to eat around others, and hiding or discarding of food.

- Purging (only in the anorexia purging subtype) with laxatives, diet pills, ipecac syrup, or diuretics to flush food out of their system after eating or engage in self-induced vomiting.

- Excessive exercise, including micro-exercising, for example making small persistent movements of fingers or toes.

- Self harming or self-loathing.

- Solitude: may avoid friends and family and become more withdrawn and secretive.

Perceptual symptoms

- Perception of self as overweight, in contradiction to an underweight reality (namely "body image disturbance" )

- Intolerance to cold and frequent complaints of being cold; body temperature may lower (hypothermia) in an effort to conserve energy due to malnutrition.

- Altered body schema (i.e. an implicit representation of the body evoked by acting)

- Altered interoception

Interoception

Interoception involves the conscious and unconscious sense of the internal state of the body, and it has an important role in homeostasis and regulation of emotions.

Aside from noticeable physiological dysfunction, interoceptive deficits

also prompt individuals with anorexia to concentrate on distorted

perceptions of multiple elements of their body image.

This exists in both people with anorexia and in healthy individuals due

to impairment in interoceptive sensitivity and interoceptive awareness.

Aside from weight gain and outer appearance, people with anorexia

also report abnormal bodily functions such as indistinct feelings of

fullness.

This provides an example of miscommunication between internal signals

of the body and the brain. Due to impaired interoceptive sensitivity,

powerful cues of fullness may be detected prematurely in highly

sensitive individuals, which can result in decreased calorie consumption

and generate anxiety surrounding food intake in anorexia patients.

People with anorexia also report difficulty identifying and describing

their emotional feelings and the inability to distinguish emotions from

bodily sensations in general, called alexithymia.

Interoceptive awareness and emotion are deeply intertwined, and could mutually impact each other in abnormalities.

Anorexia patients also exhibit emotional regulation difficulties that

ignite emotionally-cued eating behaviors, such as restricting food or

excessive exercising.

Impaired interoceptive sensitivity and interoceptive awareness can lead

anorexia patients to adapt distorted interpretations of weight gain

that are cued by physical sensations related to digestion (e.g.,

fullness).

Combined, these interoceptive and emotional elements could together

trigger maladaptive and negatively reinforced behavioral responses that

assist in the maintenance of anorexia.

In addition to metacognition, people with anorexia also have difficulty

with social cognition including interpreting others’ emotions, and

demonstrating empathy.

Abnormal interoceptive awareness and interoceptive sensitivity shown

through all of these examples have been observed so frequently in

anorexia that they have become key characteristics of the illness.

Comorbidity

Other

psychological issues may factor into anorexia nervosa. Some people have

a previous disorder which may increase their vulnerability to

developing an eating disorder and some develop them afterwards.

The presence of psychiatric comorbidity has been shown to affect the

severity and type of anorexia nervosa symptoms in both adolescents and

adults.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) are highly comorbid with AN. OCD is linked with more severe symptomatology and worse prognosis. The causality between personality disorders and eating disorders has yet to be fully established. Other comorbid conditions include depression, alcoholism, borderline and other personality disorders, anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Depression and anxiety are the most common comorbidities, and depression is associated with a worse outcome. Autism spectrum disorders occur more commonly among people with eating disorders than in the general population. Zucker et al. (2007) proposed that conditions on the autism spectrum make up the cognitive endophenotype underlying anorexia nervosa and appealed for increased interdisciplinary collaboration.

Causes

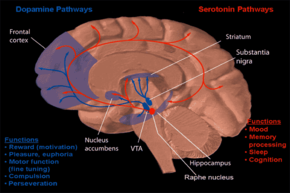

Dysregulation of the

serotonin pathways has been implicated in the cause and mechanism of anorexia.

There is evidence for biological, psychological, developmental, and

sociocultural risk factors, but the exact cause of eating disorders is

unknown.

Genetic

Genetic correlations of anorexia with psychiatric and metabolic traits.

Anorexia nervosa is highly heritable. Twin studies have shown a heritability rate of between 28 and 58%. First-degree relatives of those with anorexia have roughly 12 times the risk of developing anorexia. Association studies have been performed, studying 128 different polymorphisms related to 43 genes including genes involved in regulation of eating behavior, motivation and reward mechanics, personality traits and emotion. Consistent associations have been identified for polymorphisms associated with agouti-related peptide, brain derived neurotrophic factor, catechol-o-methyl transferase, SK3 and opioid receptor delta-1. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, may contribute to the development or maintenance of anorexia nervosa, though clinical research in this area is in its infancy.

A 2019 study found a genetic relationship with mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder and depression; and metabolic functioning with a negative correlation with fat mass, type 2 diabetes and leptin.

Environmental

Obstetric complications: prenatal and perinatal complications may factor into the development of anorexia nervosa, such as preterm birth, maternal anemia, diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, placental infarction, and neonatal heart abnormalities. Neonatal complications may also have an influence on harm avoidance, one of the personality traits associated with the development of AN.

Neuroendocrine dysregulation: altered signalling of peptides that facilitate communication between the gut, brain and adipose tissue, such as ghrelin, leptin, neuropeptide Y and orexin, may contribute to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa by disrupting regulation of hunger and satiety.

Gastrointestinal diseases:

people with gastrointestinal disorders may be more at risk of

developing disorders of eating practices than the general population,

principally restrictive eating disturbances. An association of anorexia nervosa with celiac disease has been found.

The role that gastrointestinal symptoms play in the development of

eating disorders seems rather complex. Some authors report that

unresolved symptoms prior to gastrointestinal disease diagnosis may

create a food aversion in these persons, causing alterations to their

eating patterns. Other authors report that greater symptoms throughout

their diagnosis led to greater risk. It has been documented that some

people with celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease

who are not conscious about the importance of strictly following their

diet, choose to consume their trigger foods to promote weight loss. On

the other hand, individuals with good dietary management may develop

anxiety, food aversion and eating disorders because of concerns around

cross contamination of their foods.

Some authors suggest that medical professionals should evaluate the

presence of an unrecognized celiac disease in all people with eating

disorder, especially if they present any gastrointestinal symptom (such

as decreased appetite, abdominal pain, bloating, distension, vomiting,

diarrhea or constipation), weight loss, or growth failure; and also

routinely ask celiac patients about weight or body shape concerns,

dieting or vomiting for weight control, to evaluate the possible

presence of eating disorders, especially in women.

Studies have hypothesized the continuance of disordered eating patterns may be epiphenomena of starvation. The results of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment

showed normal controls exhibit many of the behavioral patterns of AN

when subjected to starvation. This may be due to the numerous changes in

the neuroendocrine system, which results in a self-perpetuating cycle.

Anorexia nervosa is more likely to occur in a person's pubertal

years. Some explanatory hypotheses for the rising prevalence of eating

disorders in adolescence are "increase of adipose tissue in girls,

hormonal changes of puberty, societal expectations of increased

independence and autonomy that are particularly difficult for anorexic

adolescents to meet; [and] increased influence of the peer group and its

values."

Psychological

Early theories of the cause of anorexia linked it to childhood sexual abuse or dysfunctional families; evidence is conflicting, and well-designed research is needed. The fear of food is known as sitiophobia or cibophobia, and is part of the differential diagnosis.

Other psychological causes of anorexia include low self-esteem, feeling

like there is lack of control, depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Anorexic people are, in general, highly perfectionistic and most have obsessive compulsive personality traits which may facilitate sticking to a restricted diet.

It has been suggested that anorexic patients are rigid in their thought

patterns, and place a high level of importance upon being thin.

A risk factor for anorexia is trauma. Although the prevalence rates vary greatly, between 37% and 100%, there appears to be a link between traumatic events and eating disorder diagnosis.

Approximately 72% of individuals with anorexia report experiencing a

traumatic event prior to the onset of eating disorder symptoms, with

binge-purge subtype reporting the highest rates.

There are many traumatic events that may be risk factors for

development of anorexia, the first identified traumatic event predicting

anorexia was childhood sexual abuse.

However, other traumatic events, such as physical and emotional abuse

have also been found to be risk factors. Interpersonal, as opposed to

non-interpersonal trauma, has been seen as the most common type of

traumatic event, which can encompass sexual, physical, and emotional abuse.

Individuals who experience repeated trauma, like those who experience

trauma perpetrated by a caregiver or loved one, have increased symptom

severity of anorexia and a greater prevalence of comorbid psychiatric

diagnoses.

In individuals with anorexia, the prevalence rates for those who also

qualify for a PTSD diagnosis ranges from 4% to 52% in non-clinical

samples to 10% to 47% in clinical samples. A complicated symptom profile develops when trauma and anorexia meld;

the bodily experience of the individual is changed and intrusive

thoughts and sensations may be experienced.

Traumatic events can lead to intrusive and obsessive thoughts, and the

symptom of anorexia that has been most closely linked to a PTSD

diagnosis is increased obsessive thoughts pertaining to food. Similarly, impulsivity is linked to the purge and binge-purge subtypes of anorexia, trauma, and PTSD.

Emotional trauma (e.g., invalidation, chaotic family environment in

childhood) may lead to difficulty with emotions, particularly the

identification of and how physical sensations contribute to the

emotional response.

Trauma and traumatic events can disturb an individual’s sense of self

and affect their ability to thrive, especially within their bodies.

When trauma is perpetrated on an individual, it can lead to feelings of

not being safe within their own body; that their body is for others to

use and not theirs alone.

Individuals may experience a feeling of disconnection from their body

after a traumatic experience, leading to a desire to distance themselves

from the body. Trauma overwhelms individuals emotionally, physically,

and psychologically. Both physical and sexual abuse can lead to an individual seeing their body as belonging to an “other” and not to the “self”.

Individuals who feel as though they have no control over their bodies

due to trauma may use food as a means of control because the choice to

eat is an unmatched expression of control.

By exerting control over food, individuals can choose when to eat and

how much to eat. Individuals, particularly children experiencing abuse,

may feel a loss of control over their life, circumstances, and their own

bodies. Particularly sexual abuse, but also physical abuse, individuals

may feel that the body is not a safe place and an object over which

another has control. Starvation, in the case of anorexia, may also lead

to reduction in the body as a sexual object, making starvation a

solution. Restriction may also be a means by which the pain an

individual is experiencing can be communicated.

Sociological

Anorexia nervosa has been increasingly diagnosed since 1950; the increase has been linked to vulnerability and internalization of body ideals.

People in professions where there is a particular social pressure to be

thin (such as models and dancers) were more likely to develop anorexia, and those with anorexia have much higher contact with cultural sources that promote weight loss. This trend can also be observed for people who partake in certain sports, such as jockeys and wrestlers.

There is a higher incidence and prevalence of anorexia nervosa in

sports with an emphasis on aesthetics, where low body fat is

advantageous, and sports in which one has to make weight for

competition. Family group dynamics

can play a role in the cause of anorexia including negative expressed

emotion in overprotective families where blame is frequently experienced

among its members.

When there is a constant pressure from people to be thin, teasing and

bullying can cause low self-esteem and other psychological symptoms.

Media effects

Persistent

exposure to media that present body ideals may constitute a risk factor

for body dissatisfaction and anorexia nervosa. The cultural ideal for

body shape for men versus women continues to favor slender women and

athletic, V-shaped muscular men. A 2002 review found that, of the

magazines most popular among people aged 18 to 24 years, those read by

men, unlike those read by women, were more likely to feature ads and

articles on shape than on diet.

Body dissatisfaction and internalization of body ideals are risk

factors for anorexia nervosa that threaten the health of both male and

female populations.

Websites that stress the importance of attainment of body ideals

extol and promote anorexia nervosa through the use of religious

metaphors, lifestyle descriptions, "thinspiration" or "fitspiration"

(inspirational photo galleries and quotes that aim to serve as

motivators for attainment of body ideals). Pro-anorexia websites reinforce internalization of body ideals and the importance of their attainment.

The media portray a false view of what people truly look like. In

magazines and movies and even on billboards most of the actors/models

are digitally altered in multiple ways. People then strive to look like

these "perfect" role models when in reality they are not near perfection

themselves.

Mechanisms

Evidence from physiological, pharmacological and neuroimaging studies suggest serotonin

(also called 5-HT) may play a role in anorexia. While acutely ill,

metabolic changes may produce a number of biological findings in people

with anorexia that are not necessarily causative of the anorexic

behavior. For example, abnormal hormonal responses to challenges with

serotonergic agents have been observed during acute illness, but not

recovery. Nevertheless, increased cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (a metabolite of serotonin), and changes in anorectic behavior in response to acute tryptophan depletion (tryptophan is a metabolic precursor to serotonin) support a role in anorexia. The activity of the 5-HT2A receptors has been reported to be lower in patients with anorexia in a number of cortical regions, evidenced by lower binding potential of this receptor as measured by PET or SPECT,

independent of the state of illness. While these findings may be

confounded by comorbid psychiatric disorders, taken as a whole they

indicate serotonin in anorexia.

These alterations in serotonin have been linked to traits

characteristic of anorexia such as obsessiveness, anxiety, and appetite

dysregulation.

Neuroimaging studies investigating the functional connectivity

between brain regions have observed a number of alterations in networks

related to cognitive control, introspection, and sensory function.

Alterations in networks related to the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

may be related to excessive cognitive control of eating related

behaviors. Similarly, altered somatosensory integration and

introspection may relate to abnormal body image.

A review of functional neuroimaging studies reported reduced

activations in "bottom up" limbic region and increased activations in

"top down" cortical regions which may play a role in restrictive eating.

Compared to controls, recovered anorexics show reduced activation in the reward system in response to food, and reduced correlation between self reported liking of a sugary drink and activity in the striatum and anterior cingulate cortex. Increased binding potential of 11C radiolabelled raclopride in the striatum, interpreted as reflecting decreased endogenous dopamine due to competitive displacement, has also been observed.

Structural neuroimaging studies have found global reductions in

both gray matter and white matter, as well as increased cerebrospinal

fluid volumes. Regional decreases in the left hypothalamus, left inferior parietal lobe, right lentiform nucleus and right caudate have also been reported

in acutely ill patients. However, these alterations seem to be

associated with acute malnutrition and largely reversible with weight

restoration, at least in nonchronic cases in younger people. In contrast, some studies have reported increased orbitofrontal cortex volume in currently ill and in recovered patients, although findings are inconsistent. Reduced white matter integrity in the fornix has also been reported.

Diagnosis

A

diagnostic assessment includes the person's current circumstances,

biographical history, current symptoms, and family history. The

assessment also includes a mental state examination, which is an assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, focusing on views on weight and patterns of eating.

DSM-5

Anorexia nervosa is classified under the Feeding and Eating Disorders in the latest revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5). There is no specific BMI cut-off that defines low weight required for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.

The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa (all of which needing to be met for diagnosis) are:

- Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements leading to a low body weight. (Criterion A)

- Intense fear of gaining weight or persistent behaviors that interfere with gaining weight. (Criterion B)

- Disturbance in the way a person's weight or body shape is experienced or a lack of recognition about the risks of the low body weight. (Criterion C)

Relative to the previous version of the DSM (DSM-IV-TR), the 2013 revision (DSM5) reflects changes in the criteria for anorexia nervosa. Most notably, the amenorrhea (absent period) criterion was removed.

Amenorrhea was removed for several reasons: it does not apply to males,

it is not applicable for females before or after the age of

menstruation or taking birth control pills, and some women who meet the

other criteria for AN still report some menstrual activity.

Subtypes

There are two subtypes of AN:

- Binge-eating/purging type: patients with anorexia could show binge eating and purging behavior. It is different from bulimia nervosa

in terms of the individual's weight. An individual with

binge-eating/purging type anorexia is usually significantly underweight.

People with bulimia nervosa on the other hand can sometimes be normal-weight or overweight.

- Restricting type: the individual uses restricting food intake, fasting, diet pills, or exercise as a means for losing weight; they may exercise excessively to keep off weight or prevent weight gain, and some individuals eat only enough to stay alive. In the restrictive type, there are no recurrent episodes of binge-eating or purging present.

Levels of severity

Body mass index (BMI) is used by the DSM-5 as an indicator of the level of severity of anorexia nervosa. The DSM-5 states these as follows:

- Mild: BMI of greater than 17

- Moderate: BMI of 16–16.99

- Severe: BMI of 15–15.99

- Extreme: BMI of less than 15

Investigations

Medical

tests to check for signs of physical deterioration in anorexia nervosa

may be performed by a general physician or psychiatrist, including:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): a test of the white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets used to assess the presence of various disorders such as leukocytosis, leukopenia, thrombocytosis and anemia which may result from malnutrition.

- Urinalysis:

a variety of tests performed on the urine used in the diagnosis of

medical disorders, to test for substance abuse, and as an indicator of

overall health

- Chem-20: Chem-20 also known as SMA-20 a group of twenty separate chemical tests performed on blood serum. Tests include cholesterol, protein and electrolytes such as potassium, chlorine and sodium and tests specific to liver and kidney function.

- Glucose tolerance test:

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) used to assess the body's ability to

metabolize glucose. Can be useful in detecting various disorders such

as diabetes, an insulinoma, Cushing's Syndrome, hypoglycemia and polycystic ovary syndrome.

- Serum cholinesterase test: a test of liver enzymes (acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase) useful as a test of liver function and to assess the effects of malnutrition.

- Liver Function Test: A series of tests used to assess liver function some of the tests are also used in the assessment of malnutrition, protein deficiency, kidney function, bleeding disorders, and Crohn's Disease.

- Luteinizing hormone (LH) response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH): Tests the pituitary glands' response to GnRh, a hormone produced in the hypothalamus. Hypogonadism is often seen in anorexia nervosa cases.

- Creatine kinase (CK) test: measures the circulating blood levels of creatine kinase an enzyme found in the heart (CK-MB), brain (CK-BB) and skeletal muscle (CK-MM).

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test:

urea nitrogen is the byproduct of protein metabolism first formed in

the liver then removed from the body by the kidneys. The BUN test is

primarily used to test kidney function. A low BUN level may indicate the effects of malnutrition.

- BUN-to-creatinine ratio:

A BUN to creatinine ratio is used to predict various conditions. A high

BUN/creatinine ratio can occur in severe hydration, acute kidney

failure, congestive heart failure, and intestinal bleeding. A low

BUN/creatinine ratio can indicate a low protein diet, celiac disease, rhabdomyolysis, or cirrhosis of the liver.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG): measures electrical activity of the heart. It can be used to detect various disorders such as hyperkalemia.

- Electroencephalogram

(EEG): measures the electrical activity of the brain. It can be used to

detect abnormalities such as those associated with pituitary tumors.

- Thyroid screen: test used to assess thyroid functioning by checking

levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and

triiodothyronine (T3).

Differential diagnoses

A variety of medical and psychological conditions have been

misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa; in some cases the correct diagnosis

was not made for more than ten years.

The distinction between binge purging anorexia, bulimia nervosa and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders (ORFED)

is often difficult for non-specialist clinicians. A main factor

differentiating binge-purge anorexia from bulimia is the gap in physical

weight. Patients with bulimia nervosa are ordinarily at a healthy

weight, or slightly overweight. Patients with binge-purge anorexia are

commonly underweight.

Moreover, patients with the binge-purging subtype may be significantly

underweight and typically do not binge-eat large amounts of food. In contrast, those with bulimia nervosa tend to binge large amounts of food.

It is not unusual for patients with an eating disorder to "move

through" various diagnoses as their behavior and beliefs change over

time.

Treatment

There is no conclusive evidence that any particular treatment for anorexia nervosa works better than others.

Treatment for anorexia nervosa tries to address three main areas.

- Restoring the person to a healthy weight;

- Treating the psychological disorders related to the illness;

- Reducing or eliminating behaviors or thoughts that originally led to the disordered eating.

In some clinical settings a specific body image intervention is performed to reduce body dissatisfaction and body image disturbance.

Although restoring the person's weight is the primary task at hand,

optimal treatment also includes and monitors behavioral change in the

individual as well. There is some evidence that hospitalization might adversely affect long term outcome, but sometimes is necessary. Psychotherapy for individuals with AN is challenging as they may value being thin and may seek to maintain control and resist change. Initially, developing a desire to change is fundamental.

Despite no evidence for better treatment in adults patients, research

stated that family based therapy is the primary choice for adolescents

with AN.

Therapy

Family-based treatment (FBT) has been shown to be more successful than individual therapy for adolescents with AN. Various forms of family-based treatment have been proven to work in the treatment of adolescent AN including conjoint family therapy

(CFT), in which the parents and child are seen together by the same

therapist, and separated family therapy (SFT) in which the parents and

child attend therapy separately with different therapists.

Proponents of family therapy for adolescents with AN assert that it is

important to include parents in the adolescent's treatment.

A four- to five-year follow up study of the Maudsley family therapy, an evidence-based manualized model, showed full recovery at rates up to 90%. Although this model is recommended by the NIMH,

critics claim that it has the potential to create power struggles in an

intimate relationship and may disrupt equal partnerships. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is useful in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa.

One of the most known psychotherapy in the field is CBT-E, an enhanced

cognitive-behavior therapy specifically focus to eating disorder

psychopatology. Acceptance and commitment therapy is a third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapy which has shown promise in the treatment of AN. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) is also used in treating anorexia nervosa.

Schema-Focused Therapy (a form of CBT) was developed by Dr. Jeffrey

Young and is effective in helping patients identify origins and triggers

for disordered eating. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/20797222.2017.1326728

Diet

Diet is the

most essential factor to work on in people with anorexia nervosa, and

must be tailored to each person's needs. Food variety is important when

establishing meal plans as well as foods that are higher in energy

density. People must consume adequate calories, starting slowly, and increasing at a measured pace. Evidence of a role for zinc supplementation during refeeding is unclear.

Medication

Pharmaceuticals have limited benefit for anorexia itself.

There is a lack of good information from which to make recommendations

concerning the effectiveness of antidepressants in treating anorexia. Administration of olanzapine has been shown to result in a modest but statistically significant increase in body weight of anorexia nervosa patients.

Admission to hospital

AN has a high mortality

and patients admitted in a severely ill state to medical units are at

particularly high risk. Diagnosis can be challenging, risk assessment

may not be performed accurately, consent and the need for compulsion may

not be assessed appropriately, refeeding syndrome may be missed or poorly treated and the behavioural and family problems in AN may be missed or poorly managed. Guidelines published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommend that medical and psychiatric experts work together in managing severely ill people with AN.

Refeeding syndrome

The rate of refeeding can be difficult to establish, because the fear of refeeding syndrome

(RFS) can lead to underfeeding. It is thought that RFS, with falling

phosphate and potassium levels, is more likely to occur when BMI is

very low, and when medical comorbidities such as infection or cardiac

failure, are present. In those circumstances, it is recommended to

start refeeding slowly but to build up rapidly as long as RFS does not

occur. Recommendations on energy requirements vary, from 5–10

kcal/kg/day in the most medically compromised patients, who appear to

have the highest risk of RFS, to 1900 kcal/day.

Prognosis

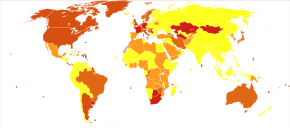

Deaths due to eating disorders per million persons in 2012

AN has the highest mortality rate of any psychological disorder. The mortality rate is 11 to 12 times greater than in the general population, and the suicide risk is 56 times higher. Half of women with AN achieve a full recovery, while an additional 20–30% may partially recover. Not all people with anorexia recover completely: about 20% develop anorexia nervosa as a chronic disorder. If anorexia nervosa is not treated, serious complications such as heart conditions and kidney failure can arise and eventually lead to death.

The average number of years from onset to remission of AN is seven for

women and three for men. After ten to fifteen years, 70% of people no

longer meet the diagnostic criteria, but many still continue to have

eating-related problems.

Alexithymia influences treatment outcome.

Recovery is also viewed on a spectrum rather than black and white.

According to the Morgan-Russell criteria, individuals can have a good,

intermediate, or poor outcome. Even when a person is classified as

having a "good" outcome, weight only has to be within 15% of average,

and normal menstruation must be present in females. The good outcome

also excludes psychological health. Recovery for people with anorexia

nervosa is undeniably positive, but recovery does not mean a return to

normal.

Complications

Anorexia

nervosa can have serious implications if its duration and severity are

significant and if onset occurs before the completion of growth,

pubertal maturation, or the attainment of peak bone mass.

Complications specific to adolescents and children with anorexia

nervosa can include the following:

Growth retardation may occur, as height gain may slow and can stop

completely with severe weight loss or chronic malnutrition. In such

cases, provided that growth potential is preserved, height increase can

resume and reach full potential after normal intake is resumed.

Height potential is normally preserved if the duration and severity of

illness are not significant or if the illness is accompanied by delayed

bone age (especially prior to a bone age of approximately 15 years), as hypogonadism

may partially counteract the effects of undernutrition on height by

allowing for a longer duration of growth compared to controls.

Appropriate early treatment can preserve height potential, and may even

help to increase it in some post-anorexic subjects, due to factors such

as long-term reduced estrogen-producing adipose tissue levels compared to premorbid levels.

In some cases, especially where onset is before puberty, complications

such as stunted growth and pubertal delay are usually reversible.

Anorexia nervosa causes alterations in the female reproductive

system; significant weight loss, as well as psychological stress and

intense exercise, typically results in a cessation of menstruation in women who are past puberty. In patients with anorexia nervosa, there is a reduction of the secretion of gonadotropin releasing hormone in the central nervous system, preventing ovulation.

Anorexia nervosa can also result in pubertal delay or arrest. Both

height gain and pubertal development are dependent on the release of

growth hormone and gonadotropins (LH and FSH) from the pituitary gland.

Suppression of gonadotropins in people with anorexia nervosa has been

documented. Typically, growth hormone (GH) levels are high, but levels of IGF-1,

the downstream hormone that should be released in response to GH are

low; this indicates a state of “resistance” to GH due to chronic

starvation. IGF-1 is necessary for bone formation, and decreased levels in anorexia nervosa contribute to a loss of bone density and potentially contribute to osteopenia or osteoporosis.

Anorexia nervosa can also result in reduction of peak bone mass.

Buildup of bone is greatest during adolescence, and if onset of anorexia

nervosa occurs during this time and stalls puberty, low bone mass may

be permanent.

Hepatic steatosis, or fatty infiltration of the liver, can also occur, and is an indicator of malnutrition in children. Neurological disorders that may occur as complications include seizures and tremors. Wernicke encephalopathy, which results from vitamin B1 deficiency, has been reported in patients who are extremely malnourished; symptoms include confusion, problems with the muscles responsible for eye movements and abnormalities in walking gait.

The most common gastrointestinal complications of anorexia nervosa are delayed stomach emptying and constipation, but also include elevated liver function tests, diarrhea, acute pancreatitis, heartburn, difficulty swallowing, and, rarely, superior mesenteric artery syndrome.

Delayed stomach emptying, or gastroparesis, often develops following

food restriction and weight loss; the most common symptom is bloating

with gas and abdominal distension, and often occurs after eating. Other

symptoms of gastroparesis include early satiety, fullness, nausea, and

vomiting. The symptoms may inhibit efforts at eating and recovery, but

can be managed by limiting high-fiber foods, using liquid nutritional

supplements, or using metoclopramide to increase emptying of food from the stomach. Gastroparesis generally resolves when weight is regained.

Cardiac complications

Anorexia nervosa increases the risk of sudden cardiac death, though the precise cause is unknown. Cardiac complications include structural and functional changes to the heart.

Some of these cardiovascular changes are mild and are reversible with

treatment, while others may be life-threatening. Cardiac complications

can include arrhythmias, abnormally slow heart beat, low blood pressure, decreased size of the heart muscle, reduced heart volume, mitral valve prolapse, myocardial fibrosis, and pericardial effusion.

Abnormalities in conduction and repolarization of the heart that can result from anorexia nervosa include QT prolongation, increased QT dispersion, conduction delays, and junctional escape rhythms.[162] Electrolyte abnormalities, particularly hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia,

can cause anomalies in the electrical activity of the heart, and result

in life-threatening arrhythmias. Hypokalemia most commonly results in

anorexic patients when restricting is accompanied by purging (induced

vomiting or laxative use). Hypotension (low blood pressure) is common,

and symptoms include fatigue and weakness. Orthostatic hypotension, a

marked decrease in blood pressure when standing from a supine position,

may also occur. Symptoms include lightheadedness upon standing,

weakness, and cognitive impairment, and may result in fainting or near-fainting. Orthostasis in anorexia nervosa indicates worsening cardiac function and may indicate a need for hospitalization.

Hypotension and orthostasis generally resolve upon recovery to a

normal weight. The weight loss in anorexia nervosa also causes atrophy of cardiac muscle. This leads to decreased ability to pump blood,

a reduction in the ability to sustain exercise, a diminished ability to

increase blood pressure in response to exercise, and a subjective

feeling of fatigue.

Some individuals may also have a decrease in cardiac

contractility. Cardiac complications can be life-threatening, but the

heart muscle generally improves with weight gain, and the heart

normalizes in size over weeks to months, with recovery. Atrophy of the heart muscle

is a marker of the severity of the disease, and while it is reversible

with treatment and refeeding, it is possible that it may cause

permanent, microscopic changes to the heart muscle that increase the

risk of sudden cardiac death. Individuals with anorexia nervosa may experience chest pain or palpitations;

these can be a result of mitral valve prolapse. Mitral valve prolapse

occurs because the size of the heart muscle decreases while the tissue

of the mitral valve

remains the same size. Studies have shown rates of mitral valve

prolapse of around 20 percent in those with anorexia nervosa, while the

rate in the general population is estimated at 2–4 percent.

It has been suggested that there is an association between mitral valve

prolapse and sudden cardiac death, but it has not been proven to be

causative, either in patients with anorexia nervosa or in the general

population.

Relapse

Rates of relapse after treatment range from 9–52% with many studies reporting a relapse rate of at least 25%.

Relapse occurs in approximately a third of people in hospital, and is

greatest in the first six to eighteen months after release from an

institution.

Epidemiology

Anorexia

is estimated to occur in 0.9% to 4.3% of women and 0.2% to 0.3% of men

in Western countries at some point in their life.

About 0.4% of young females are affected in a given year and it is

estimated to occur three to ten times less commonly in males. Rates in most of the developing world are unclear. Often it begins during the teen years or young adulthood.

The lifetime rate of atypical anorexia nervosa, a form of ED-NOS

in which the person loses a significant amount of weight and is at risk

for serious medical complications despite having a higher body-mass

index, is much higher, at 5–12%.

While anorexia became more commonly diagnosed during the 20th

century it is unclear if this was due to an increase in its frequency or

simply better diagnosis.

Most studies show that since at least 1970 the incidence of AN in adult

women is fairly constant, while there is some indication that the

incidence may have been increasing for girls aged between 14 and 20.

Underrepresentation

Eating

disorders are less reported in preindustrial, non-westernized countries

than in Western countries. In Africa, not including South Africa, the

only data presenting information about eating disorders occurs in case

reports and isolated studies, not studies investigating prevalence. Data

shows in research that in westernized civilizations, ethnic minorities

have very similar rates of eating disorders, contrary to the belief that

eating disorders predominantly occur in white people.

Men (and women) who might otherwise be diagnosed with anorexia may not meet the DSM IV criteria for BMI since they have muscle weight, but have very little fat. Male and female athletes are often overlooked as anorexic.

Research emphasizes the importance to take athletes' diet, weight and

symptoms into account when diagnosing anorexia, instead of just looking

at weight and BMI. For athletes, ritualized activities such as weigh-ins

place emphasis on gaining and losing large amounts of weight, which may

promote the development of eating disorders among them.

While women use diet pills, which is an indicator of unhealthy behavior

and an eating disorder, men use steroids, which contextualizes the

beauty ideals for genders. In a Canadian study, 4% of boys in grade nine used anabolic steroids. Anorexic men are sometimes referred to as manorexic.

Anorexia Nervosa and gender

Despite the stereotypes around eating disorders with women, one in three people with an eating disorder is male. This statistic may represent a minimum estimation. Due to the feminine stigma

attached to anorexia, many men are hesitant to seek help and remain

undiagnosed. Additionally, assessment tests are geared towards how

anorexia is experienced in women, leading to misconceptions around how

men experience anorexia. Some reports note a rise in men developing

anorexia, however this may be explained by men feeling better able to

seek help and wider recognition of the fact men experience eating disorders.

History

Two

images of an anorexic woman published in 1900 in "Nouvelle Iconographie

de la Salpêtrière". The case was titled "Un cas d'anorexie hysterique"

(A case of hysteric anorexia).

The history of anorexia nervosa begins with descriptions of religious fasting dating from the Hellenistic era

and continuing into the medieval period. The medieval practice of

self-starvation by women, including some young women, in the name of

religious piety and purity also concerns anorexia nervosa; it is

sometimes referred to as anorexia mirabilis. The earliest medical descriptions of anorexic illnesses are generally credited to English physician Richard Morton in 1689. Case descriptions fitting anorexic illnesses continued throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

The term "anorexia nervosa" was coined in 1873 by Sir William Gull, one of Queen Victoria's personal physicians. Gull published a seminal paper providing a number of detailed case descriptions of patients with anorexia nervosa. In the same year, French physician Ernest-Charles Lasègue similarly published details of a number of cases in a paper entitled De l'Anorexie hystérique.

In the late 19th century anorexia nervosa became widely accepted

by the medical profession as a recognized condition. Awareness of the

condition was largely limited to the medical profession until the latter

part of the 20th century, when German-American psychoanalyst Hilde Bruch published The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa in 1978. Despite major advances in neuroscience, Bruch's theories tend to dominate popular thinking. A further important event was the death of the popular singer and drummer Karen Carpenter in 1983, which prompted widespread ongoing media coverage of eating disorders.