From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Antisemitism in Christianity, a form of religious antisemitism, is the feeling of hostility which some Christian Churches, Christian groups, and ordinary Christians have towards the Jewish religion and the Jewish people.

Antisemitic Christian rhetoric and the antipathy towards Jews which result from it both date back to the early years of Christianity and they are derived from pagan anti-Jewish attitudes, which were reinforced by the belief that the Jews had killed Christ. Christians imposed ever-increasing anti-Jewish measures over the ensuing centuries, including acts of ostracism, humiliation, expropriation, violence, and murder, measures which culminated in The Holocaust.

Christian antisemitism has been attributed to numerous factors which include theological differences, the competition between Church and Synagogue, the Christian drive for converts,

a misunderstanding of Jewish beliefs and practices, and the perception

that Judaism was hostile towards Christianity. For two millennia, these

attitudes were reinforced in Christian preaching, art and popular

teachings, all of which expressed contempt for Jews as well as statutes which were designed to humiliate and stigmatise Jews.

Modern antisemitism has primarily been described as hatred against Jews as a race and its most recent expression is rooted in 18th-century racial theories, while anti-Judaism is rooted in hostility towards the Jewish religion, but in Western Christianity, anti-Judaism effectively merged into antisemitism during the 12th century. Scholars have debated how Christian antisemitism played a role in the Nazi Third Reich, World War II and the Holocaust. The Holocaust has forced many Christians to reflect on the relationship between Christian theology, Christian practices, and how they contributed to it.

Early differences between Christianity and Judaism

The legal status of Christianity and Judaism differed within the Roman Empire: Because the practice of Judaism was restricted to the Jewish people and Jewish proselytes, its followers were generally exempt from following the obligations that were imposed on followers of other religions by the Roman imperial cult and since the reign of Julius Caesar, it enjoyed the status of a "licit religion", but occasional persecutions still occurred, for example in 19 Tiberius expelled the Jews from Rome, as Claudius did again in 49. Christianity however was not restricted to one people, and because Jewish Christians were excluded from the synagogue (see Council of Jamnia), they also lost the protected status that was granted to Judaism, even though that protection still had its limits (see Titus Flavius Clemens (consul), Rabbi Akiva, and Ten Martyrs).

From the reign of Nero onwards, who is said by Tacitus to have blamed the Great Fire of Rome on Christians, the practice of Christianity was criminalized and Christians were frequently persecuted, but the persecution differed from region to region. Comparably, Judaism suffered setbacks due to the Jewish-Roman wars, and these setbacks are remembered in the legacy of the Ten Martyrs. Robin Lane Fox

traces the origin of much of the later hostility to this early period

of persecution, when the Roman authorities commonly tested the faith of

suspected Christians by forcing them to pay homage to the deified

emperor. Jews were exempt from this requirement as long as they paid the

Fiscus Judaicus,

and Christians (many or mostly of Jewish origin) would say that they

were Jewish but refused to pay the tax. This had to be confirmed by the

local Jewish authorities, who were likely to refuse to accept the

Christians as fellow Jews, often leading to their execution. The Birkat haMinim was often brought forward as support for this charge that the Jews were responsible for the Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire.[citation needed] In the 3rd century systematic persecution of Christians began and lasted until Constantine's conversion to Christianity. In 390 Theodosius I made Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire. While pagan cults and Manichaeism

were suppressed, Judaism retained its legal status as a licit religion,

though anti-Jewish violence still occurred. In the 5th century, some

legal measures worsened the status of the Jews in the Roman Empire.

Another point of contention for Christians concerning Judaism,

according to the modern KJV of the Protestant Bible, is attributed more

to a religious bias, rather than an issue of race or being a "Semite".

Paul (a Benjamite Hebrew) clarifies this point in the letter to the Galatians where he makes plain his declaration″

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there

is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus. And if ye be Christ's, then are ye Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise.″ Further Paul states: ″ Brethren, I speak after the manner of men; Though it be but a man's

covenant, yet if it be confirmed, no man disannulleth, or addeth

thereto. Now to Abraham and his seed were the promises

made. He saith not, And to seeds, as of many; but as of one, And to thy

seed, which is Christ.″ Many misled Christians read Matthew 23, John

8:44, Revelations 2:9, 3:9, and wrongly believe that the term "Jew"

means a Hebrew or a Semite...it does not, rather, it refers to the

religious belief in Judaism.

Issues arising from the New Testament

Jesus as the Messiah

In Judaism, Jesus was not recognized as the Messiah, which Christians interpreted as His rejection, as a failed Jewish Messiah claimant and a false prophet. However, since Jews traditionally believe that the messiah has not yet come and the Messianic Age is not yet present, the total rejection of Jesus as either the messiah or a deity has never been a central issue in Judaism.

Criticism of the Pharisees

Many New Testament passages criticise the Pharisees

and it has been argued that these passages have shaped the way that

Christians viewed Jews. Like most Bible passages, however, they can be

and have been interpreted in a variety of ways.

Mainstream Talmudic Rabbinical Judaism today directly descends from the Pharisees whom Jesus often criticized. During Jesus' life and at the time of his execution, the Pharisees were only one of several Jewish groups such as the Sadducees, Zealots, and Essenes who mostly died out not long after the period; indeed, Jewish scholars such as Harvey Falk and Hyam Maccoby have suggested that Jesus was himself a Pharisee. In the sermon on the mount,

for example, Jesus says "The Pharisees sit in Moses seat, therefore do

what they say ..". Arguments by Jesus and his disciples against certain

groups of Pharisees and what he saw as their hypocrisy were most likely

examples of disputes among Jews and internal to Judaism that were common

at the time, see for example Hillel and Shammai.

Recent studies on antisemitism in the New Testament

Professor Lillian C. Freudmann, author of Antisemitism in the New Testament (University Press of America,

1994) has published a detailed study of the description of Jews in the

New Testament, and the historical effects that such passages have had in

the Christian community throughout history. Similar studies of such

verses have been made by both Christian and Jewish scholars, including

Professors Clark Williamsom (Christian Theological Seminary), Hyam Maccoby (The Leo Baeck Institute), Norman A. Beck (Texas Lutheran College), and Michael Berenbaum

(Georgetown University). Most rabbis feel that these verses are

antisemitic, and many Christian scholars, in America and Europe, have

reached the same conclusion. Another example is John Dominic Crossan's 1995 book, titled Who Killed Jesus? Exposing the Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Gospel Story of the Death of Jesus.

Some biblical scholars have also been accused of holding antisemitic beliefs. Bruce J. Malina, a founding member of The Context Group,

has come under criticism for going as far as to deny the Semitic

ancestry of modern Israelis. He then ties this back to his work on

first-century cultural anthropology.

Jewish deicide

Jewish deicide is the belief that the Jews as a people will always be collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus, even through the successive generations following his death, also known as the blood curse.

A Biblical justification for the charge of Jewish deicide is derived

from Matthew 27:24–25, where a crowd of Jewish people told Pilate that

they and their children would be responsible for Jesus' death. The Catholic Church has repudiated this teaching, as well as several other Christian denominations. Most members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints accept the Jewish deicide.

Church Fathers

After Paul's death, Christianity emerged as a separate religion, and Pauline Christianity

emerged as the dominant form of Christianity, especially after Paul,

James and the other apostles agreed on a compromise set of requirements. Some Christians continued to adhere to aspects of Jewish law, but they were few in number and often considered heretics by the Church. One example is the Ebionites, who seems to have denied the virgin birth of Jesus, the physical Resurrection of Jesus, and most of the books that were later canonized as the New Testament. For example, the Ethiopian Orthodox still continue Old Testament practices such as the Sabbath. As late as the 4th century Church Father John Chrysostom complained that some Christians were still attending Jewish synagogues.

The Church Fathers identified Jews and Judaism with heresy and declared the people of Israel to be extra Deum (lat. "outside of God"). Peter of Antioch referred to Christians that refused to worship religious images as having "Jewish minds". In the early second century AD, the heretic Marcion of Sinope (c. 85 – c. 160 AD) declared that the Jewish God was a different God, inferior to the Christian one, and rejected the Jewish scriptures as the product of a lesser deity.

Marcion's teachings, which were extremely popular, rejected Judaism not

only as an incomplete revelation, but as a false one as well, but, at the same time, allowed less blame to be placed on the Jews personally for having not recognized Jesus,

since, in Marcion's worldview, Jesus was not sent by the lesser Jewish

God, but by the supreme Christian God, whom the Jews had no reason to

recognize.

In combating Marcion, orthodox apologists conceded that Judaism was an incomplete and inferior religion to Christianity, while also defending the Jewish scriptures as canonical. The Church Father Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240 AD) had a particularly intense personal dislike towards the Jews and argued that the Gentiles had been chosen by God to replace the Jews, because they were worthier and more honorable. Origen of Alexandria (c. 184 – c. 253) was more knowledgeable about Judaism than any of the other Church Fathers, having studied Hebrew, met Rabbi Hillel the Younger, consulted and debated with Jewish scholars, and been influenced by the allegorical interpretations of Philo of Alexandria. Origen defended the canonicity of the Old Testament and defended Jews of the past as having been chosen by God for their merits.

Nonetheless, he condemned contemporary Jews for not understanding their

own Law, insisted that Christians were the "true Israel", and blamed

the Jews for the death of Christ. He did, however, maintain that Jews would eventually attain salvation in the final apocatastasis. Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170 – c. 235 AD) wrote that the Jews had "been darkened in the eyes of your soul with a darkness utter and everlasting."

Patristic bishops of the patristic era such as Augustine argued that the Jews should be left alive and suffering as a perpetual reminder of their murder of Christ. Like his anti-Jewish teacher, Ambrose of Milan, he defined Jews as a special subset of those damned to hell. As "Witness People", he sanctified collective punishment for the Jewish deicide

and enslavement of Jews to Catholics: "Not by bodily death, shall the

ungodly race of carnal Jews perish ... 'Scatter them abroad, take away

their strength. And bring them down O Lord'". Augustine claimed to "love" the Jews but as a means to convert them to Christianity. Sometimes he identified all Jews with the evil Judas and developed the doctrine (together with Cyprian) that there was "no salvation outside the Church".

Other Church Fathers, such as John Chrysostom, went further in their condemnation. The Catholic editor Paul Harkins wrote that St. John Chrysostom's

anti-Jewish theology "is no longer tenable (..) For these objectively

unchristian acts he cannot be excused, even if he is the product of his

times." John Chrysostom held, as most Church Fathers did, that the sins

of all Jews were communal and endless, to him his Jewish neighbours were

the collective representation of all alleged crimes of all preexisting

Jews. All Church Fathers applied the passages of the New Testament

concerning the alleged advocation of the crucifixion of Christ to all

Jews of his day, the Jews were the ultimate evil. However, John

Chrysostom went so far to say that because Jews rejected the Christian God in human flesh, Christ, they therefore deserved to be killed: "grew fit for slaughter." In citing the New Testament,[Luke 19:27]

he claimed that Jesus was speaking about Jews when he said, "as for

these enemies of mine who did not want me to reign over them, bring them

here and slay them before me."

St. Jerome identified Jews with Judas Iscariot

and the immoral use of money ("Judas is cursed, that in Judas the Jews

may be accursed... their prayers turn into sins"). Jerome's homiletical

assaults, that may have served as the basis for the anti-Jewish Good Friday liturgy,

contrasts Jews with the evil, and that "the ceremonies of the Jews are

harmful and deadly to Christians", whoever keeps them was doomed to the devil:

"My enemies are the Jews; they have conspired in hatred against Me,

crucified Me, heaped evils of all kinds upon Me, blasphemed Me."

Ephraim the Syrian

wrote polemics against Jews in the 4th century, including the repeated

accusation that Satan dwells among them as a partner. The writings were

directed at Christians who were being proselytized by Jews. Ephraim

feared that they were slipping back into Judaism; thus, he portrayed the

Jews as enemies of Christianity, like Satan, to emphasize the contrast

between the two religions, namely, that Christianity was Godly and true

and Judaism was Satanic and false. Like John Chrysostom, his objective

was to dissuade Christians from reverting to Judaism by emphasizing what

he saw as the wickedness of the Jews and their religion.

Middle Ages

Bernard of Clairvaux

said "For us the Jews are Scripture's living words, because they remind

us of what Our Lord suffered. They are not to be persecuted, killed, or

even put to flight."

Jews were subjected to a wide range of legal disabilities

and restrictions in Medieval Europe. Jews were excluded from many

trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by

the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were

barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even

these at times forbidden. Jews' association to money lending would carry

on throughout history in the stereotype of Jews being greedy and

perpetuating capitalism.

In the later medieval period, the number of Jews who were

permitted to reside in certain places was limited; they were

concentrated in ghettos,

and they were also not allowed to own land; they were forced to pay

discriminatory taxes whenever they entered cities or districts other

than their own. The Oath More Judaico,

the form of oath required from Jewish witnesses, developed bizarre or

humiliating forms in some places, e.g. in the Swabian law of the 13th

century, the Jew would be required to stand on the hide of a sow or a

bloody lamb.

The Fourth Lateran Council

which was held in 1215 was the first council to proclaim that Jews were

required to wear something which distinguished them as Jews (the same

requirement was also imposed on Muslims).

On many occasions, Jews were accused of blood libels, the supposed drinking of the blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist.

Sicut Judaeis

Sicut Judaeis

(the "Constitution for the Jews") was the official position of the

papacy regarding Jews throughout the Middle Ages and later. The first bull was issued in about 1120 by Calixtus II, intended to protect Jews who suffered during the First Crusade, and was reaffirmed by many popes, even until the 15th century although they were not always strictly upheld.

The bull forbade, besides other things, Christians from coercing

Jews to convert, or to harm them, or to take their property, or to

disturb the celebration of their festivals, or to interfere with their

cemeteries, on pain of excommunication.

Popular antisemitism

Antisemitism in popular European Christian culture escalated beginning in the 13th century. Blood libels and host desecration

drew popular attention and led to many cases of persecution against

Jews. Many believed Jews poisoned wells to cause plagues. In the case of

blood libel it was widely believed that the Jews would kill a child

before Easter and needed Christian blood to bake matzo. Throughout

history if a Christian child was murdered accusations of blood libel

would arise no matter how small the Jewish population. The Church often

added to the fire by portraying the dead child as a martyr who had been

tortured and child had powers like Jesus was believed to. Sometimes the

children were even made into Saints. Antisemitic imagery such as Judensau and Ecclesia et Synagoga recurred in Christian art and architecture. Anti-Jewish Easter holiday customs such as the Burning of Judas continue to present time.

In Iceland, one of the hymns repeated in the days leading up to Easter includes the lines,

- The righteous Law of Moses

- The Jews here misapplied,

- Which their deceit exposes,

- Their hatred and their pride.

- The judgement is the Lord's.

- When by falsification

- The foe makes accusation,

- It's His to make awards.

Persecutions and expulsions

During the Middle Ages in Europe persecutions and formal expulsions

of Jews were liable to occur at intervals, although this was also the

case for other minority communities, regardless of whether they were

religious or ethnic. There were particular outbursts of riotous

persecution during the Rhineland massacres of 1096 in Germany accompanying the lead-up to the First Crusade,

many involving the crusaders as they travelled to the East. There were

many local expulsions from cities by local rulers and city councils. In

Germany the Holy Roman Emperor

generally tried to restrain persecution, if only for economic reasons,

but he was often unable to exert much influence. In the Edict of Expulsion, King Edward I

expelled all the Jews from England in 1290 (only after ransoming some

3,000 among the most wealthy of them), on the accusation of usury and undermining loyalty to the dynasty. In 1306 there was a wave of persecution in France, and there were widespread Black Death Jewish persecutions as the Jews were blamed by many Christians for the plague, or spreading it. As late as 1519, the Imperial city of Regensburg took advantage of the recent death of Emperor Maximilian I to expel its 500 Jews.

Expulsion of Jews from Spain

The largest expulsion of Jews followed the Reconquista or the reunification of Spain, and it preceded the expulsion of the Muslims who would not convert, in spite of the protection of their religious rights promised by the Treaty of Granada (1491). On 31 March 1492 Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the rulers of Spain who financed Christopher Columbus'

voyage to the New World just a few months later in 1492, declared that

all Jews in their territories should either convert to Christianity or

leave the country. While some converted, many others left for Portugal, France, Italy (including the Papal States), Netherlands, Poland, the Ottoman Empire, and North Africa. Many of those who had fled to Portugal were later expelled by King Manuel in 1497 or left to avoid forced conversion and persecution.

Renaissance to the 17th century

Cum Nimis Absurdum

On 14 July 1555, Pope Paul IV issued papal bull Cum nimis absurdum which revoked all the rights of the Jewish community and placed religious and economic restrictions on Jews in the Papal States, renewed anti-Jewish legislation and subjected Jews to various degradations and restrictions on their personal freedom.

The bull established the Roman Ghetto

and required Jews of Rome, which had existed as a community since

before Christian times and which numbered about 2,000 at the time, to

live in it. The Ghetto was a walled quarter with three gates that were

locked at night. Jews were also restricted to one synagogue per city.

Paul IV's successor, Pope Pius IV, enforced the creation of other ghettos in most Italian towns, and his successor, Pope Pius V, recommended them to other bordering states.

Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther at first made overtures towards the Jews, believing that the "evils" of Catholicism

had prevented their conversion to Christianity. When his call to

convert to his version of Christianity was unsuccessful, he became

hostile to them.

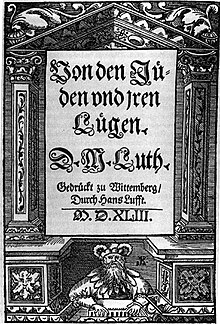

In his book On the Jews and Their Lies,

Luther excoriates them as "venomous beasts, vipers, disgusting scum,

canders, devils incarnate." He provided detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them, calling for their permanent oppression

and expulsion, writing "Their private houses must be destroyed and

devastated, they could be lodged in stables. Let the magistrates burn

their synagogues and let whatever escapes be covered with sand and mud.

Let them be forced to work, and if this avails nothing, we will be

compelled to expel them like dogs in order not to expose ourselves to

incurring divine wrath and eternal damnation from the Jews and their

lies." At one point he wrote: "...we are at fault in not slaying

them..." a passage that "may be termed the first work of modern

antisemitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."

Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a

continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism. In his final sermon

shortly before his death, however, Luther preached: "We want to treat

them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become

converted and would receive the Lord."

18th century

In accordance with the anti-Jewish precepts of the Russian Orthodox Church, Russia's discriminatory policies towards Jews intensified when the partition of Poland in the 18th century resulted, for the first time in Russian history, in the possession of land with a large Jewish population. This land was designated as the Pale of Settlement from which Jews were forbidden to migrate into the interior of Russia. In 1772 Catherine II, the empress of Russia, forced the Jews living in the Pale of Settlement to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.

19th century

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, the Roman Catholic

Church still incorporated strong antisemitic elements, despite

increasing attempts to separate anti-Judaism (opposition to the Jewish

religion on religious grounds) and racial antisemitism. Brown University

historian David Kertzer, working from the Vatican archive, has argued in his book The Popes Against the Jews

that in the 19th and early 20th centuries the Roman Catholic Church

adhered to a distinction between "good antisemitism" and "bad

antisemitism". The "bad" kind promoted hatred of Jews because of their

descent. This was considered un-Christian because the Christian message

was intended for all of humanity regardless of ethnicity; anyone could

become a Christian. The "good" kind criticized alleged Jewish conspiracies

to control newspapers, banks, and other institutions, to care only

about accumulation of wealth, etc. Many Catholic bishops wrote articles

criticizing Jews on such grounds, and, when they were accused of

promoting hatred of Jews, they would remind people that they condemned

the "bad" kind of antisemitism. Kertzer's work is not without critics.

Scholar of Jewish-Christian relations Rabbi David G. Dalin, for example, criticized Kertzer in the Weekly Standard for using evidence selectively.

Opposition to the French Revolution

The counter-revolutionary Catholic royalist Louis de Bonald stands out among the earliest figures to explicitly call for the reversal of Jewish emancipation in the wake of the French Revolution. Bonald's attacks on the Jews are likely to have influenced Napoleon's decision to limit the civil rights of Alsatian Jews. Bonald's article Sur les juifs

(1806) was one of the most venomous screeds of its era and furnished a

paradigm which combined anti-liberalism, a defense of a rural society,

traditional Christian antisemitism, and the identification of Jews with

bankers and finance capital, which would in turn influence many

subsequent right-wing reactionaries such as Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux, Charles Maurras, and Édouard Drumont, nationalists such as Maurice Barrès and Paolo Orano, and antisemitic socialists such as Alphonse Toussenel.

Bonald furthermore declared that the Jews were an "alien" people, a

"state within a state", and should be forced to wear a distinctive mark

to more easily identify and discriminate against them.

In the 1840s, the popular counter-revolutionary Catholic journalist Louis Veuillot

propagated Bonald's arguments against the Jewish "financial

aristocracy" along with vicious attacks against the Talmud and the Jews

as a "deicidal people" driven by hatred to "enslave" Christians. Gougenot des Mousseaux's Le Juif, le judaïsme et la judaïsation des peuples chrétiens (1869) has been called a "Bible of modern antisemitism" and was translated into German by Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.

Between 1882 and 1886 alone, French priests published twenty

antisemitic books blaming France's ills on the Jews and urging the

government to consign them back to the ghettos, expel them, or hang them

from the gallows.

In Italy the Jesuit priest Antonio Bresciani's highly popular novel 1850 novel L'Ebreo di Verona (The Jew of Verona) shaped religious antisemitism for decades, as did his work for La Civiltà Cattolica, which he helped launch.

Pope Pius VII (1800–1823) had the walls of the Jewish ghetto in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were emancipated by Napoleon, and Jews were restricted to the ghetto through the end of the Papal States in 1870. Official Catholic organizations, such as the Jesuits,

banned candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is

clear that their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have

belonged to the Catholic Church" until 1946.

20th century

In

Russia, under the Tsarist regime, antisemitism intensified in the early

years of the 20th century and was given official favour when the secret

police forged the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document purported to be a transcription of a plan by Jewish elders to achieve global domination. Violence against the Jews in the Kishinev pogrom in 1903 was continued after the 1905 revolution by the activities of the Black Hundreds. The Beilis Trial of 1913 showed that it was possible to revive the blood libel accusation in Russia.

Catholic writers such as Ernest Jouin, who published the Protocols

in French, seamlessly blended racial and religious antisemitism, as in

his statement that "from the triple viewpoint of race, of nationality,

and of religion, the Jew has become the enemy of humanity." Pope Pius XI praised Jouin for "combating our mortal [Jewish] enemy" and appointed him to high papal office as a protonotary apostolic.

WWI to the eve of WWII

In 1916, in the midst of the First World War, American Jews petitioned Pope Benedict XV on behalf of the Polish Jews.

Nazi antisemitism

During a meeting with Roman Catholic Bishop Wilhelm Berning [de] of Osnabrück On April 26, 1933, Hitler declared:

“I have been attacked because of my handling of the Jewish question.

The Catholic Church considered the Jews pestilent for fifteen hundred

years, put them in ghettos, etc., because it recognized the Jews for

what they were. In the epoch of liberalism the danger was no longer

recognized. I am moving back toward the time in which a

fifteen-hundred-year-long tradition was implemented. I do not set race

over religion, but I recognize the representatives of this race as

pestilent for the state and for the Church, and perhaps I am thereby

doing Christianity a great service by pushing them out of schools and

public functions.”

The transcript of the discussion does not contain any response by Bishop Berning. Martin Rhonheimer

does not consider this unusual because in his opinion, for a Catholic

Bishop in 1933 there was nothing particularly objectionable "in this

historically correct reminder".

The Nazis used Martin Luther's book, On the Jews and Their Lies (1543), to justify their claim

that their ideology was morally righteous. Luther even went so far as

to advocate the murder of Jews who refused to convert to Christianity by

writing that "we are at fault in not slaying them."

Archbishop Robert Runcie

asserted that: "Without centuries of Christian antisemitism, Hitler's

passionate hatred would never have been so fervently echoed... because

for centuries Christians have held Jews collectively responsible for the

death of Jesus.

On Good Friday Jews, have in times past, cowered behind locked doors

with fear of a Christian mob seeking 'revenge' for deicide. Without the

poisoning of Christian minds through the centuries, the Holocaust is

unthinkable." The dissident Catholic priest Hans Küng

has written that "Nazi anti-Judaism was the work of godless,

anti-Christian criminals. But it would not have been possible without

the almost two thousand years' pre-history of 'Christian'

anti-Judaism..." The consensus among historians is that Nazism as a whole was either unrelated or actively opposed to Christianity, and Hitler was strongly critical of it, although Germany remained mostly Christian during the Nazi era.

The document Dabru Emet was issued by over 220 rabbis and intellectuals from all branches of Judaism in 2000 as a statement about Jewish-Christian relations. This document states,

"Nazism

was not a Christian phenomenon. Without the long history of Christian

anti-Judaism and Christian violence against Jews, Nazi ideology could

not have taken hold nor could it have been carried out. Too many

Christians participated in, or were sympathetic to, Nazi atrocities

against Jews. Other Christians did not protest sufficiently against

these atrocities. But Nazism itself was not an inevitable outcome of

Christianity."

According to American historian Lucy Dawidowicz, antisemitism has a long history within Christianity. The line of "antisemitic descent" from Luther, the author of On the Jews and Their Lies, to Hitler is "easy to draw." In her The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945,

she contends that Luther and Hitler were obsessed by the "demonologized

universe" inhabited by Jews. Dawidowicz writes that the similarities

between Luther's anti-Jewish writings and modern antisemitism are no

coincidence, because they derived from a common history of Judenhass, which can be traced to Haman's advice to Ahasuerus. Although modern German antisemitism also has its roots in German nationalism and the liberal revolution of 1848, Christian antisemitism she writes is a foundation that was laid by the Roman Catholic Church and "upon which Luther built."

Collaborating Christians

Opposition to the Holocaust

The Confessing Church

was, in 1934, the first Christian opposition group. The Catholic Church

officially condemned the Nazi theory of racism in Germany in 1937 with

the encyclical "Mit brennender Sorge", signed by Pope Pius XI, and Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber led the Catholic opposition, preaching against racism.

Many individual Christian clergy and laypeople of all denominations had to pay for their opposition with their lives, including:

By the 1940s, few Christians were willing to publicly oppose Nazi

policy, but many Christians secretly helped save the lives of Jews.

There are many sections of Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Museum, Yad Vashem, which are dedicated to honoring these "Righteous Among the Nations".

Pope Pius XII

Before he became Pope, Cardinal Pacelli addressed the International Eucharistic Congress in Budapest

on 25–30 May 1938 during which he made reference to the Jews "whose

lips curse [Christ] and whose hearts reject him even today"; at this

time antisemitic laws were in the process of being formulated in

Hungary.

The 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge was issued by Pope Pius XI, but drafted by the future Pope Pius XII

and read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches, it condemned

Nazi ideology and has been characterized by scholars as the "first

great official public document to dare to confront and criticize Nazism" and "one of the greatest such condemnations ever issued by the Vatican."

In the summer of 1942, Pius explained to his college of Cardinals

the reasons for the great gulf that existed between Jews and Christians

at the theological level: "Jerusalem has responded to His call and

to His grace with the same rigid blindness and stubborn ingratitude that

has led it along the path of guilt to the murder of God." Historian Guido Knopp describes these comments of Pius as being "incomprehensible" at a time when "Jerusalem was being murdered by the million". This traditional adversarial relationship with Judaism would be reversed in Nostra aetate, which was issued during the Second Vatican Council.

Prominent members of the Jewish community have contradicted the

criticisms of Pius and spoke highly of his efforts to protect Jews. The Israeli historian Pinchas Lapide

interviewed war survivors and concluded that Pius XII "was instrumental

in saving at least 700,000, but probably as many as 860,000 Jews from

certain death at Nazi hands". Some historians dispute this estimate.

"White Power" movement

The Christian Identity movement, the Ku Klux Klan and other White supremacist

groups have expressed antisemitic views. They claim that their

antisemitism is based on purported Jewish control of the media, control

of international banks, involvement in radical left-wing politics, and the Jews' promotion of multiculturalism, anti-Christian groups, liberalism and perverse organizations. They rebuke charges of racism

by claiming that Jews who share their views maintain membership in

their organizations. A racial belief which is common among these groups,

but not universal among them, is an alternative history doctrine concerning the descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel. In some of its forms, this doctrine absolutely denies the view that modern Jews have any ethnic connection to the Israel of the Bible. Instead, according to extreme forms of this doctrine, the true Israelites and the true humans are the members of the Adamic (white) race. These groups are often rejected and they are not even considered Christian groups by mainstream Christian denominations and the vast majority of Christians around the world.

Post World War II antisemitism

Antisemitism

remains a substantial problem in Europe and to a greater or lesser

degree, it also exists in many other nations, including Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, and tensions between some Muslim immigrants and Jews have increased across Europe. The US State Department reports that antisemitism has increased dramatically in Europe and Eurasia since 2000.

While it has been on the decline since the 1940s, a measurable amount of antisemitism still exists in the United States, although acts of violence are rare. For example, the influential Evangelical preacher Billy Graham and the then-president Richard Nixon were caught on tape in the early 1970s while they were discussing matters like how to address the Jews' control of the American media. This belief in Jewish conspiracies and domination of the media was similar to those of Graham's former mentors: William Bell Riley chose Graham to succeed him as the second president of Northwestern Bible and Missionary Training School and evangelist Mordecai Ham led the meetings where Graham first believed in Christ. Both held strongly antisemitic views. The 2001 survey by the Anti-Defamation League

reported 1432 acts of antisemitism in the United States that year. The

figure included 877 acts of harassment, including verbal intimidation,

threats and physical assaults. A minority of American churches engage in anti-Israel activism, including support for the controversial BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions)

movement. While not directly indicative of antisemitism, this activism

often conflates the Israeli government's treatment of Palestinians with

that of Jesus, thereby promoting the antisemitic doctrine of Jewish guilt. Many Christian Zionists are also accused of antisemitism, such as John Hagee, who argued that the Jews brought the Holocaust upon themselves by angering God.

Relations between Jews and Christians have dramatically improved

since the 20th century. According to a global poll which was conducted

in 2014 by the Anti-Defamation League, a Jewish group which is devoted to fighting antisemitism and other forms of racism,

data was collected from 102 countries with regard to their population's

attitudes towards Jews and it revealed that only 24% of the world's

Christians held views which were considered antisemitic according to the

ADL's index, compared to 49% of the world's Muslims.

Anti-Judaism

Many Christians do not consider anti-Judaism to be antisemitism. They regard anti-Judaism as a disagreement with the tenets of Judaism

by religiously sincere people, while they regard antisemitism as an

emotional bias or hatred which does not specifically target the religion

of Judaism. Under this approach, anti-Judaism is not regarded as

antisemitism because it does not involve actual hostility towards the

Jewish people, instead, anti-Judaism only rejects the religious beliefs

of Judaism.

Others believe that anti-Judaism is rejection of Judaism as a religion or opposition to Judaism's beliefs and practices essentially because of their source in Judaism or because a belief or practice is associated with the Jewish people. (But see supersessionism)

The position that "Christian theological anti-Judaism is a

phenomenon which is distinct from modern antisemitism, which is rooted

in economic and racial thought, so that Christian teachings should not

be held responsible for antisemitism" has been articulated, among other people, by Pope John Paul II in 'We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah,' and the Jewish declaration on Christianity, Dabru Emet. Several scholars, including Susannah Heschel, Gavin I Langmuir and Uriel Tal have challenged this position, by arguing that anti-Judaism directly led to modern antisemitism.

Although some Christians did consider anti-Judaism to be contrary

to Christian teaching in the past, this view was not widely expressed

by Christian leaders and lay people. In many cases, the practical

tolerance towards the Jewish religion and Jews prevailed. Some Christian

groups condemned verbal anti-Judaism, particularly in their early

years.

Conversion of Jews

Some Jewish organizations have denounced evangelistic and missionary

activities which specifically target Jews by labeling them antisemitic.

The Southern Baptist Convention

(SBC), the largest Protestant Christian denomination in the U.S., has

explicitly rejected suggestions that it should back away from seeking to

convert Jews, a position which critics have called antisemitic, but a

position which Baptists

believe is consistent with their view that salvation is solely found

through faith in Christ. In 1996 the SBC approved a resolution calling

for efforts to seek the conversion of Jews "as well as the salvation of

'every kindred and tongue and people and nation.'"

Most Evangelicals

agree with the SBC's position, and some of them also support efforts

which specifically seek the Jews' conversion. Additionally, these

Evangelical groups are among the most pro-Israel groups. (For more information, see Christian Zionism.) One controversial group which has received a considerable amount of support from some Evangelical churches is Jews for Jesus, which claims that Jews can "complete" their Jewish faith by accepting Jesus as the Messiah.

The Presbyterian Church (USA), the United Methodist Church, and the United Church of Canada have ended their efforts to convert Jews. While Anglicans do not, as a rule, seek converts from other Christian denominations,

the General Synod has affirmed that "the good news of salvation in

Jesus Christ is for all and must be shared with all including people

from other faiths or of no faith and that to do anything else would be

to institutionalize discrimination".

The Roman Catholic Church

formerly operated religious congregations which specifically aimed to

convert Jews. Some of these congregations were actually founded by

Jewish converts, like the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion, whose members were nuns and ordained priests. Many Catholic saints were specifically noted for their missionary zeal to convert Jews, such as Vincent Ferrer. After the Second Vatican Council, many missionary orders which aimed to convert Jews to Christianity no longer actively sought to missionize (or proselytize) them. However, Traditionalist Roman Catholic

groups, congregations and clergymen continue to advocate the

missionizing of Jews according to traditional patterns, sometimes with

success (e.g., the Society of St. Pius X which has notable Jewish converts among its faithful, many of whom have become traditionalist priests).

The Church's Ministry Among Jewish People (CMJ) is one of the ten official mission agencies of the Church of England. The Society for Distributing Hebrew Scriptures is another organisation, but it is not affiliated with the established Church.

There are several prophecies concerning the conversion of the Jewish people to Christianity in the scriptures of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). The Book of Mormon teaches that the Jewish people need to believe in Jesus to be gathered to Israel. The Doctrine & Covenants

teaches that the Jewish people will be converted to Christianity during

the second coming when Jesus appears to them and shows them his wounds. It teaches that if the Jewish people do not convert to Christianity, then the world would be cursed. Early LDS prophets, such as Brigham Young and Wildord Woodruff, taught that Jewish people could not be truly converted because of the curse which resulted from Jewish deicide. However, after the establishment of the state of Israel, many LDS

members felt that it was time for the Jewish people to start converting

to Mormonism.

During the 1950s, the LDS Church established several missions which

specifically targeted Jewish people in several cities in the United

States.

After the LDS church began to give the priesthood to all males

regardless of race in 1978, it also started to deemphasize the

importance of race with regard to conversion.

This led to a void of doctrinal teachings that resulted in a spectrum

of views in how LDS members interpret scripture and previous teachings. According to research which was conducted by Armand Mauss,

most LDS members believe that the Jewish people will need to be

converted to Christianity in order to be forgiven for the crucifixion of

Jesus Christ.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has also been criticized for baptizing deceased Jewish Holocaust victims.

In 1995, in part as a result of public pressure, church leaders

promised to put new policies into place that would help the church to

end the practice, unless it was specifically requested or approved by

the surviving spouses, children or parents of the victims. However, the practice has continued, including the baptism of the parents of Holocaust survivor and Jewish rights advocate Simon Wiesenthal.

Reconciliation between Judaism and Christian groups

In recent years, there has been much to note in the way of reconciliation between some Christian groups and the Jews.