The economic history of the United Kingdom relates the economic development in the British state from the absorption of Wales into the Kingdom of England after 1535 to the modern United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland of the early 21st century.

Scotland, England, and Wales shared a monarch from 1601 but their economies were run separately until they were unified in the 1707 Act of Union. Ireland was incorporated in the United Kingdom economy between 1800 and 1922; from 1922 the Irish Free State (the modern Republic of Ireland) became independent and set its own economic policy.

Great Britain, and England in particular, became one of the most prosperous economic regions in the world between the late 1600s and early 1800s as a result of being the birthplace of the industrial revolution that began in the mid-eighteenth century. The developments brought by industrialization resulted in Britain becoming the premier European and global economic, political, and military power for more than a century. As the first to industrialize, Britain's industrialists revolutionized areas like manufacturing, communication, and transportation through innovations such as the steam engine (for pumps, factories, railway locomotives and steamships), textile equipment, tool-making, the Telegraph, and pioneered the railway system. With these many new technologies Britain manufactured much of the equipment and products used by other nations, becoming known as the "workshop of the world". Its businessmen were leaders in international commerce and banking, trade and shipping. Its markets included both areas that were independent and those that were part of the rapidly expanding British Empire, which by the early 1900s had become the largest empire in history. After 1840, the economic policy of mercantilism was abandoned and replaced by free trade, with fewer tariffs, quotas or restrictions, first outlined by British economist Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations. Britain's globally dominant Royal Navy protected British commercial interests, shipping and international trade, while the British legal system provided a system for resolving disputes relatively inexpensively, and the City of London functioned as the economic capital and focus of the world economy.

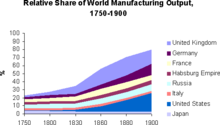

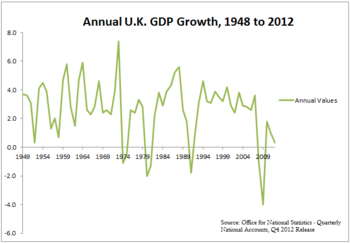

Between 1870 and 1900, economic output per head of the United Kingdom rose by 50 per cent (from about £28 per capita to £41 in 1900: an annual average increase in real incomes of 1% p.a.), growth which was associated with a significant rise in living standards. However, and despite this significant economic growth, some economic historians have suggested that Britain experienced a relative economic decline in the last third of the nineteenth century as industrial expansion occurred in the United States and Germany. In 1870, Britain's output per head was the second highest in the world, surpassed only by Australia. In 1914, British income per capita was the world's third highest, exceeded only by New Zealand and Australia; these three countries shared a common economic, social and cultural heritage. In 1950, British output per head was still 30 per cent over that of the average of the six founder members of the EEC, but within 20 years it had been overtaken by the majority of western European economies.

The response of successive British governments to this problematic performance was to seek economic growth stimuli within what became the European Union; Britain entered the European Community in 1973. Thereafter the United Kingdom's relative economic performance improved substantially to the extent that, on the eve of the 2007 financial crisis, British income per capita exceeded, albeit marginally, that of France and Germany; furthermore, there was a significant reduction in the gap in income per capita terms between the UK and USA.

16th–17th centuries

During 16th and 17th century many fundamental economic changes occurred, these resulted in rising incomes and paved the way to the industrialisation. After 1600, the North Sea Region took over the role of the leading economic centre of Europe from the Mediterranean, which prior to this date, particularly in northern Italy, had been the most highly developed part of Europe. Great Britain, together with the Low Countries, profited more in the long run from the expansion of trade in the Atlantic and Asia than the pioneers of this trade, Spain and Portugal, fundamentally because of the success of the mainly privately owned enterprises in these two Northern countries in contrast to the arguably less successful state-owned economic systems in Iberia.

Following the Black Death in the mid 14th century, and the agricultural depression of the late 15th century, the population began to increase. The export of woollen products resulted in an economic upturn with products exported to mainland Europe. Henry VII negotiated the favourable Intercursus Magnus treaty in 1496.

The high wages and abundance of available land seen in the late 15th century and early 16th century were temporary. When the population recovered, low wages and a land shortage returned. Historians in the early 20th century characterized the economic in terms of general decline, manorial reorganization, and agricultural contraction. Later historians dropped those themes and stressed the transitions between medieval forms and Tudor progress.

John Leland left rich descriptions of the local economies he witnessed during his travels 1531 to 1560. He described markets, ports, industries, buildings and transport links. He showed some small towns were expanding, through new commercial and industrial opportunities, especially cloth manufacture. He found other towns in decline, and suggested that investment by entrepreneurs and benefactors had enabled some small towns to prosper. Taxation was a negative factor in economic growth, since it was imposed, not on consumption, but on capital investments.

According to Derek Hirst, outside of politics and religion, the 1640s and 1650s saw a revived economy characterized by growth in manufacturing, the elaboration of financial and credit instruments, and the commercialization Of communication. The gentry found time for leisure activities, such as horse racing and bowling. In the high culture important innovations included the development of a mass market for music, increased scientific research, and an expansion of publishing. All the trends were discussed in depth at the newly established coffee houses.

Growth in money supply

Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the New World exported large quantities of silver and gold to Europe, some of which added to the English money supply. There were multiple results that all expanded the English economy, according to Dr. Nuno Palma of the University of Manchester. The key features of the growth pattern included specialisation and structural change, and increases in market participation. The new supply of specie (silver and gold) increased the money supply. Instead of promissory notes paid off by future promissory notes, business transactions were supported by specie. This reduced transaction costs, increased the coverage of the market, and opened incentives and opportunities to participate in cash transaction. Demand arose for luxury goods from Asia, such as silk and pepper, which created new markets. The increased supply of specie made tax collection easier, allowing the government to build up fiscal capacity and provide for public goods.

Various inflationary pressures existed; some were due to an influx of New World gold and a rising population. Inflation had a negative effect on the real wealth of most families. It set the stage for social upheaval as the gap between the rich and poor widening. This was a period of significant change for the majority of the rural population, with manorial land owners introducing enclosure measures.

Exports

Exports increased significantly, especially within the British empire. Mostly privately owned companies traded with the colonies in the West Indies, Northern America and India.

The Company of Merchant Adventurers of London brought together London's leading overseas merchants in a regulated company in the early 15th century, in the nature of a guild. Its members' main business was the export of cloth, especially white (undyed) woollen broadcloth. This enabled them to import a large range of foreign goods. Given the trade conditions of the time, England came up with a public policy to increase Armenian merchant's involvement in English trade to pursue its commercial interests. Accordingly, in 1688 a trade agreement was signed in London between English East India Company and Kjoja Panos Kalantar. Armenian merchants received privileges to carry out commercial activities in England. England, in its turn, wanted to change the main trade route from Europe to Asia, and from now on, Armenians, instead of overlanding in Arabia or Persia, used England. With this agreement, England wanted to take over the control that Dutch and France had at that time on world exports.

Wool industry

Woollen cloth was the chief export and most important employer after agriculture. The golden era of the Wiltshire woollen industry was in the reign of Henry VIII. In the medieval period, raw wool had been exported, but now England had an industry, based on its 11 million sheep. London and towns purchased wool from dealers, and send it to rural households where family labour turned it into cloth. They washed the wool, carded it and spun it into thread, which was then turned into cloth on a loom. Export merchants, known as Merchant Adventurers, exported woollens into the Netherlands and Germany, as well as other lands. The arrival of Huguenots from France brought in new skills that expanded the industry.

Government intervention proved a disaster in the early 17th century. A new company convinced Parliament to transfer to them the monopoly held by the old, well-established Company of Merchant Adventurers. Arguing that the export of unfinished cloth was much less profitable than the export of the finished product, the new company got Parliament to ban the export of unfinished cloth. There was massive dislocation marketplace, as large unsold quantities built up, prices fell, and unemployment rose. Worst of all, the Dutch retaliated and refused to import any finished cloth from England. Exports fell by a third. Quickly the ban was lifted, and the Merchant Adventurers got its monopoly back. However, the trade losses became permanent.

Diets

Diet depended largely upon social class. The rich ate meat—beef, pork, venison and white bread; the poor ate coarse dark bread, with a little meat, notably at Christmas. Game poaching supplemented the diet of the rural poor. Everyone drank ale or cider as water was often too impure to drink. Fruits and vegetables were seldom eaten. Rich spices were used by the wealthy to offset the smells of stale salted meat. The potato had yet to become part of the diet. The rich enjoyed desserts such as pastries, tarts, cakes, and crystallized fruit, and syrup.

Among the rich private hospitality was an important item in their budget. Entertaining a royal party for a few weeks could be ruinous to a nobleman. Inns existed for travellers but restaurants were not known.

Both the rich and the poor had diets with nutritional deficiency. The lack of vegetables and fruits in their diets caused a deficiency in vitamin C, sometimes resulting in scurvy.

Trade and industry flourished in the 16th century, making England more prosperous and improving the standard of living of the upper and middle classes. However, the lower classes did not benefit much and did not always have enough food. As the English population was fed by its own agricultural produce, a series of bad harvests in the 1590s caused widespread distress.

In the 17th century the food supply improved. England had no food crises from 1650 to 1725, a period when France was unusually vulnerable to famines. Historians point out that oat and barley prices in England did not always increase following a failure of the wheat crop, but did so in France.

Poverty

About one-third of the population lived in poverty, with the wealthy expected to give alms to assist the impotent poor. Tudor law was harsh on the able-bodied poor, those physically fit but unable to find work. Those who left their parishes in order to locate work were termed vagabonds and could be subjected to punishments, often suffering whipping and being put in the stocks. This treatment was inflicted to encourage them to return to their "mother parish."

18th century

The trading nation

The 18th century was prosperous as entrepreneurs extended the range of their business around the globe. By the 1720s Britain was one of the most prosperous countries in the world, and Daniel Defoe boasted: "We are the most diligent nation in the world. Vast trade, rich manufactures, mighty wealth, universal correspondence, and happy success have been constant companions of England, and given us the title of an industrious people."

While the other major powers were primarily motivated toward territorial gains, and protection of their dynasties (such as the Habsburg , Rurik dynasty and Prussia's House of Hohenzollern), Britain had a different set of primary interests. Its main diplomatic goal (besides protecting the homeland from invasion) was building a worldwide trading network for its merchants, manufacturers, shippers and financiers. This required a hegemonic Royal Navy so powerful that no rival could sweep its ships from the world's trading routes, or invade the British Isles. The London government enhanced the private sector by incorporating numerous privately financed London-based companies for establishing trading posts and opening import-export businesses across the world. Each was given a monopoly of trade to the specified geographical region. The first enterprise was the Muscovy Company set up in 1555 to trade with Russia. Other prominent enterprises included the East India Company, and the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa had been set up in 1662 to trade in gold, ivory and slaves in Africa; it was reestablished as the Royal African Company in 1672 and focused on the Atlantic slave trade. British involvement in each of the four major wars, 1740 to 1783, paid off handsomely in terms of trade. Even the loss of the Thirteen Colonies was made up by a very favourable trading relationship with the new United States of America. Britain gained dominance in the trade with India, and largely dominated the highly lucrative slave, sugar, and commercial trades originating in West Africa and the West Indies. Exports soared from £6.5 million in 1700, to £14.7 million in 1760 and £43.2 million in 1800. Other powers set up similar monopolies on a much smaller scale; only the Netherlands emphasised trade as much as England.

Most of the companies earned good profits, and enormous personal fortunes were created in India. However, there was one major fiasco that caused heavy losses. The South Sea Bubble was a business enterprise that exploded in scandal. The South Sea Company was a private business corporation supposedly set up much like the other trading companies, with a focus on South America. Its actual purpose was to renegotiate previous high-interest government loans amounting to £31 million through market manipulation and speculation. It issued stock four times in 1720 that reached about 8,000 investors. Prices kept soaring every day, from £130 a share to £1,000, with insiders making huge paper profits. The Bubble collapsed overnight, ruining many speculators. Investigations showed bribes had reached into high places—even to the king. His chief minister Robert Walpole managed to wind it down with minimal political and economic damage, although some losers fled to exile or committed suicide.

The age of mercantilism

The basis of the British Empire was founded in the age of mercantilism, an economic theory that stressed maximising the trade outside the empire, and trying to weaken rival empires. The 18th century British Empire was based upon the preceding English overseas possessions, which began to take shape in the late 16th and early 17th century, with the English settlement of islands of the West Indies such as Trinidad and Tobago, the Bahamas, the Leeward Islands, Barbados, Jamaica, and Bermuda, and of Virginia, one of the Thirteen Colonies which in 1776 became the United States, as well as of the Maritime provinces of what is now Canada. The sugar plantation islands of the Caribbean, where slavery became the basis of the economy, comprised England's most lucrative colonies. The American colonies also used slave labour in the farming of tobacco, indigo, and rice in the south. England, and later Great Britain's, American empire was slowly expanded by war and colonisation. Victory over the French during the Seven Years' War gave Great Britain control over what is now eastern Canada.

Mercantilism was the basic policy imposed by Britain on its colonies. Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants—and kept others out—by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximise exports from and minimise imports to the realm. The Navigation Acts of the late 17th century provided the legal foundation for Mercantilist policy. They required all trade to be carried in English ships, manned by English crews (this later encompassed all Britons after the Acts of Union 1707 united Scotland with England). Colonists were required to send their produce and raw materials first of all to Britain, where the surplus was then sold-on by British merchants to other colonies in the British empire or bullion-earning external markets. The colonies were forbidden to trade directly with other nations or rival empires. The goal was to maintain the North American and Caribbean colonies as dependent agricultural economies geared towards producing raw materials for export to Britain. The growth of native industry was discouraged, in order to keep the colonies dependent on Britain for their finished goods.

The government had to fight smuggling—which became a favourite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch. The goal of mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a superb Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. Thus the British Navy captured New Amsterdam (New York City) in 1664. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.

Manufacturing

Besides woollens, cotton, silk and linen cloth manufacturing became important after 1600, as did coal and iron.

In 1709, Abraham Darby I established a coke-fired blast furnace to produce cast iron, replacing charcoal, although continuing to use blast furnaces. The ensuing availability of inexpensive iron was one of the factors leading to the Industrial Revolution. Toward the end of the 18th century, cast iron began to replace wrought iron for certain purposes, because it was cheaper. Carbon content in iron was not implicated as the reason for the differences in properties of wrought iron, cast iron, and steel until the 18th century.

The Industrial Revolution

In period loosely dated from the 1770s to the 1820s, Britain experienced an accelerated process of economic change that transformed a largely agrarian economy into the world's first industrial economy. This phenomenon is known as the "industrial revolution", since the changes were far-reaching and permanent throughout many areas of Britain, especially in the developing cities.

Economic, institutional, and social changes were fundamental to the emergence of the industrial revolution. Whereas absolutism remained the normal form of governance through most parts of Europe, in the UK a fundamentally different power balance was created after the revolutions of 1640 and 1688. The new institutional setup ensured property rights and political safety and thereby supported the emergence of an economically prosperous middle class. Another factor is the change in marriage patterns through this period. Marrying later allowed young people to acquire more education, thereby building up more human capital in the population. These changes enhanced the already relatively developed labour and financial markets, paving the way for the industrial revolution starting in the mid-18th century.

Great Britain provided the legal and cultural foundations that enabled entrepreneurs to pioneer the industrial revolution. Starting in the later part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great Britain's previously manual labour and draft-animal–based economy towards machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. Factories pulled thousands from low productivity work in agriculture to high productivity urban jobs.

The introduction of steam power fuelled primarily by coal, wider utilisation of water wheels and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialisation. The historian Emma Griffin has placed particular emphasis on the role of the steam engine in the making of Britain's industrial revolution.

According to Max Weber, the foundations of this process of change can be traced back to the Puritan Ethic of the Puritans of the 17th century. This produced modern personalities attuned to innovation and committed to a work ethic, inspiring landed and merchant elites alive to the benefits of modernization, and a system of agriculture able to produce increasingly cheap food supplies. To this must be added the influence of religious nonconformity, which increased literacy and inculcated a "Protestant work ethic" amongst skilled artisans.

A long run of good harvests, starting in the first half of the 18th century, resulted in an increase in disposable income and a consequent rising demand for manufactured goods, particularly textiles. The invention of the flying shuttle by John Kay enabled wider cloth to be woven faster, but also created a demand for yarn that could not be fulfilled. Thus, the major technological advances associated with the industrial revolution were concerned with spinning. James Hargreaves created the Spinning Jenny, a device that could perform the work of a number of spinning wheels. However, while this invention could be operated by hand, the water frame, invented by Richard Arkwright, could be powered by a water wheel. Indeed, Arkwright is credited with the widespread introduction of the factory system in Britain, and is the first example of the successful mill owner and industrialist in British history. The water frame was, however, soon supplanted by the spinning mule (a cross between a water frame and a jenny) invented by Samuel Crompton. Mules were later constructed in iron by Messrs. Horrocks of Stockport.

As they were water powered, the first mills were constructed in rural locations by streams or rivers. Workers villages were created around them, such as New Lanark Mills in Scotland. These spinning mills resulted in the decline of the domestic system, in which spinning with old slow equipment was undertaken in rural cottages.

The steam engine was invented and became a power supply that soon surpassed waterfalls and horsepower. The first practicable steam engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen, and was used for pumping water out of mines. A much more powerful steam engine was invented by James Watt; it had a reciprocating engine capable of powering machinery. The first steam-driven textile mills began to appear in the last quarter of the 18th century, and this transformed the industrial revolution into an urban phenomenon, greatly contributing to the appearance and rapid growth of industrial towns.

The progress of the textile trade soon outstripped the original supplies of raw materials. By the turn of the 19th century, imported American cotton had replaced wool in the North West of England, though wool remained the chief textile in Yorkshire. Textiles have been identified as the catalyst in technological change in this period. The application of steam power stimulated the demand for coal; the demand for machinery and rails stimulated the iron industry; and the demand for transportation to move raw material in and finished products out stimulated the growth of the canal system, and (after 1830) the railway system.

Such an unprecedented degree of economic growth was not sustained by domestic demand alone. The application of technology and the factory system created such levels of mass production and cost efficiency that enabled British manufacturers to export inexpensive cloth and other items worldwide.

Walt Rostow has posited the 1790s as the "take-off" period for the industrial revolution. This means that a process previously responding to domestic and other external stimuli began to feed upon itself, and became an unstoppable and irreversible process of sustained industrial and technological expansion.

In the late 18th century and early 19th century a series of technological advances led to the Industrial Revolution. Britain's position as the world's pre-eminent trader helped fund research and experimentation. The nation also had some of the world's greatest reserves of coal, the main fuel of the new revolution.

It was also fuelled by a rejection of mercantilism in favour of the predominance of Adam Smith's capitalism. The fight against Mercantilism was led by a number of liberal thinkers, such as Richard Cobden, Joseph Hume, Francis Place and John Roebuck.

Some have stressed the importance of natural or financial resources that Britain received from its many overseas colonies or that profits from the British slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean helped fuel industrial investment, citing "bigger markets for British goods, larger profits to British investors, more and cheaper raw materials for emerging industrial sectors, and more incentives for British consumers than were offered by domestic industries or other foreign markets".

The Industrial Revolution saw a rapid transformation in the British economy and society. Previously, large industries had to be near forests or rivers for power. The use of coal-fuelled engines allowed them to be placed in large urban centres. These new factories proved far more efficient at producing goods than the cottage industry of a previous era. These manufactured goods were sold around the world, and raw materials and luxury goods were imported to Britain.

Empire

During the Industrial Revolution the empire became less important and less well-regarded. The British defeat in the American War of Independence (1775–1783) deprived it of its largest and most developed colonies. This loss brought a realisation that colonies were not particularly economically beneficial to the home economy. It was realised that the costs of occupation of colonies often exceeded the financial return to the taxpayer. In other words, formal empire afforded no great economic benefit when trade would continue whether the overseas political entities were nominally sovereign or not. The American Revolution helped demonstrate this by showing that Britain could still control trade with the colonies without having to pay for their defence and governance. This encouraged the British to grant their colonies self-government, starting with Canada, which became unified and largely independent in 1867, and Australia, which followed suit in 1901.

Napoleonic Wars

Critical to British success in confronting Napoleon was its superior economic situation. It was able to mobilize the nation's industrial and financial resources and apply them to defeating the First French Empire. With a population of 16 million Britain was barely half the size of France with 30 million. In terms of soldiers, the French numerical advantage was offset by British subsidies that paid for a large proportion of the Austrian and Russian soldiers, peaking at about 450,000 in 1813.

Most important, the British national output remained strong. Textiles and iron grew sharply. Iron production expanded as demand for cannon and munitions was insatiable. Agricultural prices soared—it was a golden age for agriculture even as food shortages appeared here and there. There were riots in Cornwall, Devon, and Somerset during the food shortages of 1800–01. Mobs forced merchants to hand over their stocks, as the food was distributed to the hungry by popular committees. Wells concludes that the disturbances indicate deep social grievances that extended far beyond the immediate food shortages. Overall, however, crop production grew 50% between 1795 and 1815.

The system of smuggling finished products into the continent undermined French efforts to ruin the British economy by cutting off markets. The well-organized business sector channelled products into what the military needed. Not only did British cloth provide for British uniforms, it clothed the allies as well and indeed the French soldiers too. Britain used its economic power to expand the Royal Navy, doubling the number of frigates and increasing the number of large ships of the line by 50%, while increasing the roster of sailors from 15,000 to 133,000 in eight years after the war began in 1793. France, meanwhile, saw its navy shrink by more than half.

The British budget in 1814 reached £66 million, including £10 million for the Navy, £40 million for the Army, £10 million for the Allies, and £38 million as interest on the national debt. The national debt soared to £679 million, more than double the GDP. It was willingly supported by hundreds of thousands of investors and tax payers, despite the higher taxes on land and a new income tax. The whole cost of the war came to £831 million. By contrast the French financial system was inadequate and Napoleon's forces had to rely in part on requisitions from conquered lands.

Long-term favourable impact

O'Brien examines the long-term economic impact of the wars of 1793–1815, and finds them generally favourable, except for damage to the working class. The economy was not damaged by the diversion of manpower to the army and navy; in terms of destruction and enforced transfer of national wealth, Britain came out ahead. British control of the oceans proved optimal in creating a liberal free-trade global economy, and helped Britain gain the lion's share of the world's carrying trade and financial support services. The effects were positive for agriculture and most industries, apart from construction. The rate of capital formation was slowed somewhat and national income perhaps would have grown even faster without war. The most negative impact was a drop in living standards for the urban working classes.

19th century

19th century Britain was the world's richest and most advanced economy while 19th century Ireland experienced the worst famine in Europe in that century. Real GDP per person almost doubled in the 90 years between 1780 and 1870, when it reached $3263 per capita. This was one third greater than GDP per person in the United States, and 70% more than both France and Germany. The economy was the most industrialized in the world, with one-third of the population employed in manufacturing by 1870 (concurrently one-sixth of the workforce in the United States was employed in manufacturing). The level of quantifiable steam power (in both industry and railroad travel), was gauged at 7,600 hp in 1880, only excelled by the United States. Urbanization was so intense that by 1901 80% of the British population lived in towns. The number of towns with a population over 50,000 reached 32 between 1847 and 1850, double that of Germany and almost five times that of the United States. By 1901 there were 74 British towns which met the 50,000 minimum threshold.

Free trade

Free trade was intellectually established by 1780 and implemented in the 1840s, thanks to the unusually strong influence of political theorists such as Adam Smith. They convincingly argued that the old policy of mercantilism held back the British economy, which if unfettered was poised to dominate world trade. As predicted, British dominance of world trade was apparent by the 1850s.

After 1840, Britain committed its economy to free trade, with few barriers or tariffs. This was most evident in the repeal in 1846 of the Corn Laws, which had imposed stiff tariffs on imported grain. The end of these laws opened the British market to unfettered competition, grain prices fell, and food became more plentiful in Britain, the main island of the then United Kingdom. The same was not true in Ireland where the 1840s saw the worst famine in Europe in that century. By re-introducing income taxes in 1842 at the rate of 7 pence on the pound for incomes over £150, the government of Sir Robert Peel was able to compensate for loss of revenue and repeal import duties on over 700 items.

From 1815 to 1870, Britain reaped the benefits of being the world's first modern, industrialised nation. It described itself as 'the workshop of the world', meaning that its finished goods were produced so efficiently and cheaply that they could often undersell comparable, locally manufactured goods in almost any other market. If political conditions in a particular overseas market were stable enough, Britain could dominate its economy through free trade alone without having to resort to formal rule or mercantilism. Britain was even supplying half the needs in manufactured goods of such nations as Germany, France, Belgium, and the United States. By 1820, 30% of Britain's exports went to its Empire, rising slowly to 35% by 1910. Until the latter 19th century, India remained Britain's economic jewel in terms of both imports and exports. In 1867, when British exports to her Empire totaled £50 million, £21 million of that was earned from India's market alone. Second to India, but far behind, was Australia, whose imports from Britain totaled £8 million, followed by Canada (£5.8 million), Hong Kong (£2.5 million), Singapore (£2 million), and New Zealand (£1.6 million). While these figures were undoubtedly significant, they represented just over a third of total British exports, the same proportion as over forty years before.

Apart from coal, iron, tin and kaolin most raw materials had to be imported so that, in the 1830s, the main imports were (in order): raw cotton (from the American South), sugar (from the West Indies), wool, silk, tea (from China), timber (from Canada), wine, flax, hides and tallow. By 1900, Britain's global share had soared to 22.8% of total imports. By 1922, its global share was 14.9% of total exports and 28.8% of manufactured exports.

However, while in the 1890s Britain persisted in its free trade policy its major rivals, the U.S. and Germany, turned to high and moderately high tariffs respectively. American heavy industry grew faster than Britain and by the 1890s was competing with British machinery and other products in the world market.

In the decades before the First World War, Britain's exports were elastic to (increasing) foreign tariffs, with one study estimating that Britain's exports would have been 57% higher in 1902, under the counterfactual scenario of worldwide free trade.

Imperialism of Free Trade

Historians agree that in the 1840s, Britain adopted a free-trade policy, meaning open markets and no tariffs throughout the empire. The debate among historians involves what the implications of free trade actually were. "The Imperialism of Free Trade" is a highly influential 1952 article by John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson. They argued that the New Imperialism of the 1880s, especially the Scramble for Africa, was a continuation of a long-term policy in which informal empire, based on the principles of free trade, was favoured over formal imperial control. The article helped launch the Cambridge School of historiography. Gallagher and Robinson used the British experience to construct a framework for understanding European imperialism that swept away the all-or-nothing thinking of previous historians. They found that European leaders rejected the notion that "imperialism" had to be based upon formal, legal control by one government over a colonial region. Much more important was informal influence in independent areas. According to Wm. Roger Louis, "In their view, historians have been mesmerized by formal empire and maps of the world with regions colored red. The bulk of British emigration, trade, and capital went to areas outside the formal British Empire. Key to their thinking is the idea of empire 'informally if possible and formally if necessary.'" Oron Hale says that Gallagher and Robinson looked at the British involvement in Africa where they, "found few capitalists, less capital, and not much pressure from the alleged traditional promoters of colonial expansion. Cabinet decisions to annex or not to annex were made, usually on the basis of political or geopolitical considerations."

Reviewing the debate from the end of the 20th century, historian Martin Lynn argues that Gallagher and Robinson exaggerated the impact. He says that Britain achieved its goal of increasing its economic interests in many areas, "but the broader goal of 'regenerating' societies and thereby creating regions tied as 'tributaries' to British economic interests was not attained." The reasons were:

the aim to reshape the world through free trade and its extension overseas owed more to the misplaced optimism of British policy-makers and their partial views of the world than to an understanding of the realities of the mid-19th century globe ... the volumes of trade and investment...the British were able to generate remained limited ... Local economies and local regimes proved adept at restricting the reach of British trade and investment. Local impediments to foreign inroads, the inhabitants' low purchasing power, the resilience of local manufacturing, and the capabilities of local entrepreneurs meant that these areas effectively resisted British economic penetration.

Agriculture

A free market for imported foodstuffs, the driving factor behind the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws, reaped long-term benefits for consumers in Great Britain as world agricultural production increased. Consumers in Ireland, where there was severe famine in the 1840s, did not benefit to the same extent. At first agriculture in Great Britain, through its superior productivity, was able to weather and even thrive following the repeal of the Corn Laws, contrary to the dire warnings of the landowners who had warned of immediate agricultural ruin. By the 1870s, the global price of grain began to fall dramatically following the opening up of the Midwestern United States and interior of Canada to mechanized cultivation. Combined with lower global transportation costs, the average price of a quarter of grain fell from 56s in the years 1867–71, to 27s 3d per quarter in 1894–98. This lowered the cost of living and enabled Britain to meet the demands of a quickly growing population (grain imports tripled in volume between 1870 and 1914, while the population grew 43% between 1871 and 1901). It also caused the Great Depression of British Agriculture in the countryside by the late 1870s, where a series of bad harvests combined with the far cheaper price of foreign grain induced a long decline for the British agricultural sector. Wheat-producing areas like East Anglia were especially hard hit, with overall wheat cultivation down from 13% of agricultural output in 1870, to 4% in 1900. Landowners argued for a re-introduction of the Corn Laws to protect domestic farming, but this was rebuffed by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, who argued that returning to protectionism would endanger British manufacturing supremacy.

In addition to the general slump in demand, greater mechanization in British agriculture, typified by the introduction of steam-powered threshing machines, mowers, and reapers, increased unemployment for rural workers. The result was an acceleration of migration from country to town, where jobs in factories, domestic service, and other occupations offered better wages and more opportunities. The male workforce of the countryside decreased by 40% between 1861 and 1901, while agriculture as a percentage of the national wealth fell from 20.3% in 1851 to just 6.4% by 1901. The depression did not apply only to foodstuffs, but also to wool producers, a once vital sector undercut by a flood of cheap wool imports from Australia and New Zealand. Only select types of produce where freshness was imperative, like milk and meat, enjoyed strong domestic demand in the late 19th century.

The declining profitability of agriculture in the latter decades of the 19th century left British landowners hard pressed to maintain their accustomed lifestyles. The connection between land ownership and wealth which had for centuries underpinned the British aristocracy began an inexorable decline. Rents fell some 26% between the mid-1870s and mid-1890s, just as the amount of land under cultivation fell some 19%. 88% of British millionaires between the years 1809–1879 were defined as landowners; the proportion fell to 33% in the years 1880–1914, as a new class of plutocrats emerged from industry and finance.

Recessions

Britain's 19th century economic growth was beset by frequent and sometimes severe recessions. The Post-Napoleonic depression following the end of the Wars in 1815 was induced by several years of poor harvests, which were aggravated by the Corn Laws of 1815. This law set high tariffs on imported foodstuffs, keeping the cost of grain artificially high while wages were declining. As early as 1816, the high cost of grain caused famine and unrest in areas such as East Anglia and the North of England, where rioters seized grain stores and attacked the homes of suspected profiteers and merchants. The high food prices caused an overall slump in consumption and consequently in industrial production and employment. The discontent of the workers culminated in the disastrous confrontation with the authorities at the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, when British cavalry rode headfirst into a crowd of 60,000 to 80,000 protesters in Manchester, killing 5 and wounding as many as 700 people.

The recession of the "Hungry Forties" was similar in its nature to that of the 1820s. Like that of the years following 1815, the 1840s recession was caused by a series of bad harvests, this time from a blight affecting potatoes facilitated by unusually wet and cold conditions in Northern Europe. Ireland, where the population was heavily dependent on potatoes for subsistence, was the worst affected. On mainland Britain, regions of the Scottish Highlands and the Outer Hebrides were worst affected by the potato blight (some parts were depopulated by as much as 50%). The Corn Laws inhibited the ability of the British government to import food for the starving in Ireland and Scotland, which led the Tory Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel to defy the landed interests in Parliament and force the abolition of the Corn Laws in June 1846. The abolition was only accomplished in phases through 1849, by which time Ireland and the Highlands had lost much of their populations to famine or emigration. Relief funding by the British government for the famine in Ireland was dramatically cut in 1847 because of the financial crisis that year. Many blamed the crisis on Peel's wider economic policy but the repeal of the Corn Laws, combined with the astronomic growth of the railways, served to lift Britain out of recession in the 1850s, providing the basis for steady growth in population and output over the next few decades.

Railways

The British invented the modern railway system and exported it to the world. This emerged from Britain's elaborate system of canals and roadways, which both used horses to haul coal. Domestic consumption in household heaths remained an important market though coal also fired the new steam engines installed in textile factories. Britain furthermore had the engineers and entrepreneurs needed to create and finance a railway system. In 1815, George Stephenson invented the modern steam locomotive, launching a technological race: bigger, more powerful locomotives using higher and higher steam pressures. Stephenson's key innovation came when he integrated all the components of a railways system in 1825 by opening the Stockton and Darlington line. It demonstrated it was commercially feasible to have a system of usable length. London poured money into railway building—a veritable bubble, but one with permanent value.

Thomas Brassey brought British railway engineering to the world, with construction crews that in the 1840s employed 75,000 men across Europe. Every nation copied the British model. Brassey expanded throughout the British Empire and Latin America. His companies invented and improved thousands of mechanical devices, and developed the science of civil engineering to build roadways, tunnels and bridges.

The telegraph, although invented and developed separately, proved essential for the internal communications of the railways. They allowed slower trains to pull over as express trains raced through; made it possible to use a single track for two-way traffic, and to locate where repairs were needed.

In the early period, recognition of the potential of the railways along with led to a period of speculation and investment referred to as Railway Mania. The boom years were 1836 and 1845–47, when Parliament authorized 8,000 miles of railways with a projected future total of £200 million; that about equalled one year of Britain's GDP. Once a charter was obtained, there was little government regulation, as laissez faire and private ownership had become accepted practices. Britain had a superior financial system based in London that funded both the railways in Britain and also in many other parts of the world, including the United States, up until 1914.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859) designed the first major railway, the Great Western, built originally in the 1830s to cover the 100 miles from London to Bristol. Even more important was the highly controversial George Hudson. He became Britain's "railway king" by merging numerous short lines. Since there was no government agency supervising the railways, Hudson set up a system that all the lines adopted called the Railway Clearing House. It made interconnections easy for people and freight by standardizing routines for transferring freight and people between companies, and loaning out freight cars. By 1849 Hudson controlled nearly 30% of Britain's trackage. Hudson did away with accountants and manipulated funds—paying large dividends out of capital because profits were quite low, but no one knew that until his system collapsed and the railway bubble of the late 1840s burst.

By 1850 Britain had a well integrated, well engineered system that provided fast, on-time, inexpensive movement of freight and people to every city and most rural districts. Freight rates had plunged to a penny a ton mile for coal. The system directly or indirectly employed tens of thousands of engineers, conductors, mechanics, repairmen, accountants, station agents and managers, bringing a new level of business sophistication that could be applied to many other industries, and helping many small and large businesses to expand their role in the industrial revolution. Thus railways had a tremendous impact on industrialization. By lowering transportation costs, they reduced costs for all industries moving supplies and finished goods, and they increased demand for the production of all the inputs needed for the railway system itself. The system kept growing; by 1880, there were 13,500 locomotives which each carried 97,800 passengers a year, or 31,500 tons of freight.

Second Industrial Revolution

During the First Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant as the dominant figure in the capitalist system. In the later decades of the 19th century, when the ultimate control and direction of large industry came into the hands of financiers, industrial capitalism gave way to financial capitalism and the corporation. The establishment of behemoth industrial empires, whose assets were controlled and managed by men divorced from production, was a dominant feature of this third phase. By the middle of the 19th century, as the world's only fully industrialized nation, British output represented just under half the total of the world's industrial capacity.

New products and services were also introduced which greatly increased international trade. Improvements in steam engine design and the wide availability of cheap iron (and after 1870 steel) meant that slow, sailing ships could be replaced with steamships, such as Brunel's SS Great Western. Electricity and chemical industries became important although Britain lagged behind the U.S. and Germany.

Amalgamation of industrial cartels into larger corporations, mergers and alliances of separate firms, and technological advancement (particularly the increased use of electric power and internal combustion engines fuelled by petrol) were mixed blessings for British business during the late Victorian era. The ensuing development of more intricate and efficient machines along with mass production techniques greatly expanded output and lowered production costs. As a result, production often exceeded domestic demand. Among the new conditions, more markedly evident in Britain, the forerunner of Europe's industrial states, were the long-term effects of the severe Long Depression of 1873–1896, which had followed fifteen years of great economic instability. Businesses in practically every industry suffered from lengthy periods of low — and falling — profit rates and price deflation after 1873.

By the 1870s, financial houses in London had achieved an unprecedented level of control over industry. This contributed to increasing concerns among policy-makers over the protection of British investments overseas — particularly those in the securities of foreign governments and in foreign-government-backed development activities, such as railways. Although it had been official British policy to support such investments, with the large expansion of these investments in the 1860s, and the economic and political instability of many areas of investment (such as Egypt), calls upon the government for methodical protection became increasingly pronounced in the years leading up to the Crystal Palace Speech. At the end of the Victorian era, the service sector (banking, insurance and shipping, for example) began to gain prominence at the expense of manufacturing. During the late 18th century the United Kingdom experienced stronger increases in the service sector than in the industrial sector; industry grew by only 2 per cent, whereas the service sector employment increased by 9 per cent.

Foreign trade

Foreign trade tripled in volume between 1870 and 1914; most of the activity occurred with other industrialised countries. Britain ranked as the world's largest trading nation in 1860, but by 1913 it had lost ground to both the United States and Germany: British and German exports in the latter year each totalled $2.3 billion, and those of the United States exceeded $2.4 billion. Although her own exports were diminishing in comparison to her rivals, Britain remained the world's largest trading nation by a significant margin: in 1914 her import and export totals were larger by a third compared to Germany, and larger by 50 per cent compared to the United States. Britain was a top importer of foodstuffs, raw materials, and finished goods, much of which were re-exported to Europe or the United States. In 1880 Britain purchased about half the world total in traded tea, coffee, and wheat, and just under half of the world's meat exports. In that same year, more than 50 per cent of world shipping was British owned, while British shipyards were constructing about four fifths of the world's new vessels in the 1890s.[112]

Its extensive trading contacts, investments in agriculture, and merchant shipping fleet enabled it to trade in a great volume of commodities remotely - transactions were concluded with foreign clients from London or other British cities over distant commodities like coffee, tea, cotton, rubber, and sugar. Proportionally, even though trade volumes trebled between 1870 and 1914, the British share of the world market was actually shrinking. In 1880, 23 per cent of world trade was British-owned - by 1910 it was 17 per cent. As foreign trade increased, so in proportion did the amount of it going outside the Continent. In 1840, £7.7 million of its export and £9.2 million of its import trade was done outside Europe; in 1880 the figures were £38.4 million and £73 million. Europe's economic contacts with the wider world were multiplying, much as Britain's had been doing for years. In many cases, colonial control followed private investment, particularly in raw materials and agriculture. Intercontinental trade between North and South constituted a higher proportion of global trade in this era than in the late 20th century period of globalisation.[

American invasion and British response

The American "invasion" of some sections of the British home market for manufactured goods prompted a commercial response. Tariffs, despite sustained political campaign for Protection in the first decade of the twentieth century, were only imposed generally after the collapse of the world trade in 1930. In this competitive milieu, British businessmen modernised their operations; for example, manufactures of boots and shoes faced increasing imports of American footwear and Americans entered the market for shoe-making machinery. British shoe-makers realised that to meet this competition it was necessary to re-examine their traditional methods of work, labour utilisation, and industrial relations; they also had to be more responsive to the demands of fashion.

Export of capital

The City of London strengthened its position as the world's financial capital, the export of capital was a major base of the British economy 1880 to 1913, the "golden era" of international finance. By 1913 about 50% of capital investment throughout the world had been raised in London, making Britain the largest exporter of capital by a wide margin. Although the British trade deficit widened (£27 million in 1851, by 1911 it was £134 million), earnings from investment and financial services more than closed the gap and generated a substantial Balance of Payments surplus. Part of the reason for the initial boom in financial services was because manufacturing became less profitable beginning in the 1880s, due to the largely depressed world market of these years, combined with the expansion of manufacturing in the United States and Germany. With foreign competition in some manufacturing sectors fiercer than in mid-century, British industrialists and financiers more profitably invested increasing quantities of capital abroad. In 1911, income from overseas investments amounted to £188 million; income from services like insurance, shipping, and banking totalled some £152 million. It is indicative of the notable shift to financial services that between 1900 and 1913 total British investment abroad doubled, increasing from £2 billion to £4 billion. In the late nineteenth century, Britain's foreign investment raised its merchandise exports to capital-receiving countries, since, at the time, Britain was both the world's workshop and the world's creditor.

British overseas investment was especially impressive in the independent nations of Latin America, which were eager for infrastructure improvements, such as railways and ports, that were often built by British contracting firms, and telegraph and telephone systems. Contemporaneously, British merchants dominated international trade in Latin America. Inevitably, not all these investments paid off; for example, many British investors suffered substantial losses after investing in railway companies in the United States that went bankrupt, while even some mining ventures in the Sudan also proved unprofitable.

Business practices

Big business grew much more slowly in Britain than in the United States, with the result that by the late 19th century the much larger American corporations were growing faster and could undersell the smaller competitors in Britain. A key was the vertical integration. In the United States, the typical firm expanded by reaching backward into the supply chain and forward into the distribution system. In the Ford Motor Company, raw iron and coal went in one end, and Model Ts were delivered by local dealers at the other end, British firms did not try to own the sources of raw materials, they bought on the market. Instead of setting up their own distribution system they worked with well-established wholesalers. The British businessmen were much more comfortable and a smaller niche, even though it made it much harder to lower costs and prices. Furthermore, the Americans had a rapidly growing home market, and Investment Capital was much more readily available. British businessmen typically used their savings not to expand their business but to purchase highly prestigious country estates – they looked to the landed country gentry for their role model, whereas Americans looked to the multi-millionaires. Crystal Palace hosted a world class industrial exhibition in 1851 in London. It was a marvelous display of the latest achievements in material progress, clearly demonstrating British superiority. The Americans were impressed, and repeatedly opened world–class industrial exhibits. By contrast, the British never repeated their success. In 1886 British sociologist Herbert Spencer commented: "Absorbed by his activities, and spurred on by his unrestricted ambitions, the American is a less happy being than the inhabitant of a country where the possibilities of success are very much smaller."

Organization

As industrialisation took effect in the late 18th and early 19th century, the United Kingdom possessed a strong national government that provided a standard currency, an efficient legal system, efficient taxation, and effective support for overseas enterprise both within the British Empire and in independent nations. Parliament repealed medieval laws that restricted business enterprise, such as specification of how many threads could be in a woollen cloth, or regulating interest rates. Taxation fell primarily on landed wealth, not accumulated capital nor income. In 1825 Parliament repealed the Bubble Act of 1720 and facilitated capital accumulation. After the General Enclosure Act of 1801, farming became more productive and feed the growing urban industrial workforce. The Navigation Acts remained important into the 1820s, and enforced by the Royal Navy, facilitated international trade. The road system was developed through government-sponsored local turnpikes. However, there were few examples of government-financed canals, and none of railroads, unlike early major transport projects in Japan, in Russia, or in the mid-nineteenth century USA.

Evidence from Lever Brothers, Royal Dutch Shell, and Burroughs Wellcome indicates that after 1870 individual entrepreneurship by top leaders was critical in fostering the growth of direct foreign investment and the rise to prominence of multinational corporations. In 1929, the first modern multinational company emerged when a merger of Dutch Margarine Unie and British soapmaker Lever Brothers resulted in Unilever. With 250,000 people employed, and in terms of market value, Unilever was the largest industrial company in Europe. However, after 1945 the importance of entrepreneurship declined in British business.

Accounting

New business practices in the areas of management and accounting made possible the more efficient operation of large companies. For example, in steel, coal, and iron companies 19th-century accountants used sophisticated, fully integrated accounting systems to calculate output, yields, and costs to satisfy management information requirements. South Durham Steel and Iron, was a large horizontally integrated company that operated mines, mills, and shipyards. Its management used traditional accounting methods with the goal of minimizing production costs, and thus raising its profitability. By contrast one of its competitors, Cargo Fleet Iron introduced mass production milling techniques through the construction of modern plants. Cargo Fleet set high production goals and developed an innovative but complicated accounting system to measure and report all costs throughout the production process. However, problems in obtaining coal supplies and the failure to meet the firm's production goals forced Cargo Fleet to drop its aggressive system and return to the sort of approach South Durham Steel was using.

Imperialism

After the loss of the American colonies in 1776, Britain built a "Second British Empire", based in colonies in India, Asia, Australia, Canada. The crown jewel was India, where in the 1750s a private British company, with its own army, the East India Company (or "John Company"), took control of parts of India. The 19th century saw Company rule extended across India after expelling the Dutch, French and Portuguese. By the 1830s the company was a government and had given up most of its business in India, but it was still privately owned. Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 the government closed down the company and took control of British India and the company's Presidency Armies.

Free trade (with no tariffs and few trade barriers) was introduced in the 1840s. Protected by the overwhelming power of the Royal Navy, the economic empire included very close economic ties with independent nations in Latin America. The informal economic empire has been called "The Imperialism of Free Trade."

Numerous independent entrepreneurs expanded the Empire, such as Stamford Raffles of the East India Company who founded the port of Singapore in 1819. Businessmen eager to sell Indian opium in the vast China market led to the Opium War (1839–1842) and the establishment of British colonies at Hong Kong. One adventurer, James Brooke, set himself up as the Rajah of the Kingdom of Sarawak in North Borneo in 1842; his realm joined the Empire in 1888. Cecil Rhodes set up an economic empire of diamonds in South Africa that proved highly profitable. There were great riches in gold and diamonds but this venture led to expensive wars with the Dutch settlers known as Boers.

The possessions of the East India Company in India, under the direct rule of the Crown from 1857 —known as British India— was the centrepiece of the Empire, and because of an efficient taxation system it paid its own administrative expenses as well as the cost of the large British Indian Army. In terms of trade, however, India turned only a small profit for British business. However, transfers to the British government was massive: in 1801 unrequited (unpaid, or paid from Indian-collected revenue) was about 30% of British domestic savings available for capital formation in Britain.

There was pride and glory in the Empire, as talented young Britons vied for positions in the Indian Civil Service and for similar overseas career opportunities. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was a vital economic and military link. Britain continued to expand their control in areas strategically important to the link with India, including Egypt and Cyprus.

Cain and Hopkins argue that the phases of expansion abroad were closely linked with the development of the domestic economy. Therefore, the shifting balance of social and political forces under imperialism and the varying intensity of Britain's economic and political rivalry with other powers need to be understood with reference to domestic policies. Gentlemen capitalists, representing Britain's landed gentry and London's service sectors and financial institutions, largely shaped and controlled Britain's imperial enterprises in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Industrial leaders played a lesser role and found themselves dependent on the gentlemen capitalists.

Long Depression

The last and longest lasting of the 19th century recessions was the Long Depression, which began with the financial Panic of 1873 and induced a twenty three-year period of worldwide anemic growth and recession cycles which only ended in the late 1890s. The bursting of a railroad speculation bubble in the United States, heavily financed via London, was a major factor in the initial shock. British foreign investment fell sharply, but it took some years for record high domestic investments to fall as well. The initial Depression lasted between 1873 and 1879, and was marked above all by price deflation, and therefore declining profitability for industrialists and financiers. Shrinking returns and a generally unfavorable economic climate meant that investment as a percentage of Britain's National wealth, both overseas and at home, fell from an average of 12.6% between 1870 and 1874, to 9.7% between 1875 and 1896. The sluggish world market, which was at its weakest in the 1880s, was keenly felt in the export-reliant economy of the UK. British quinquennial export averages did not return to their pre-1873 levels (£235 million between 1870 and 1874) until 1895–99, slumping to £192 million in 1879. The recovery, moreover, was weaker than the mid-century growth in exports, because British manufactures were struggling to compete with domestically produced products in nations like Germany and the United States, where steep exclusionary tariffs had been enforced in response to the economic crisis. Prices on commodities in Britain fell as much as 40% in the 1870s, with a downward pressure on wages which led to a general perception among the working classes of financial hardship and decline.

To a great extent, Britain's economic difficulties were symptomatic of structural weaknesses that were beginning to manifest themselves by the 1870s. Economists have explained the relative slowdown in growth during the latter 19th century in terms of the Neoclassical growth model, in which the momentum from decades of growth was reaching an inevitable slow down. Endogenous growth theory suggests that this slowdown was attributable to national institutions and conditions, such as entrepreneurship, natural resources, and outward investment, rather than subject to a naturally occurring external model. It is not surprising then, that countries with markedly larger natural resources, and larger populations to draw from, should have overtaken the UK in terms of production by the end of the nineteenth century. Britain depended on imports to supplement her deficiencies of some natural resources, but the high cost of shipping made this impracticable when competing against the resource-rich giant, the United States. The result was clearly measured: the UK averaged 1.8% annual growth between 1873 and 1913, while the United States and Germany averaged 4.8% and 3.9% per annum respectively. Historians have criticized cultural and educational factors for contributing to a decline in the "entrepreneurial spirit" which had characterized the Industrial Revolution. The offspring of first and second-generation industrialists in the late 19th-century, raised in privilege and educated at aristocratically dominated public schools, showed little interest in adopting their father's occupations because of the stigma attached to working in manufacturing or "trade". Moreover, the curricula of the public schools and universities was overwhelmingly centered on the study of Classics, which left students ill-prepared to innovate in the manufacturing world. Many turned away from industry and entered the more "gentlemanly" financial sector, the law courts, or the civil service of the Empire.

However, the statistical evidence counters any of perception of economic stagnation in the latter 19th century: the employed labour force grew, unemployment in the years 1874–1890 only averaged 4.9%, and productivity continued to rise after the 1870s recession, albeit at a lower annual rate of 1%, compared to 2% in the years preceding the Panic of 1873. Moreover, because of the decline in prices overall, living standards improved markedly during the "Long Depression" decades. Real GDP per capita fluctuated by the year, but as a whole rose steadily from $3870 in 1873 to $5608 by 1900, exceeding all nations in terms of per capita wealth except Australia and the United States. The heavy investment levels of pre-1873 began to yield returns, so that British income from abroad surpassed outward investment and created a steady surplus to support the widening balance of trade. The export of capital investment, even though it occupied a smaller percentage of the national wealth, recovered briskly beginning in 1879, reaching record highs in the following decade (£56.15 million between 1876 and 1895, compared to £33.74 between 1851 and 1874). The trend towards investing British capital abroad in the late 19th century (about 35% of British assets were held abroad by 1913) has been blamed for essentially starving native industry of investment which could have been used to maintain competitiveness and increase productivity.

One of the causes for the 1873 panic was attributed to overproduction in industry. British industrialists believed they had produced more than could be sold on saturated domestic and overseas markets, so they began to lobby the British government and public opinion to expand the British Empire. According to this theory, Britain's trade deficit could be corrected, and excess production absorbed, by these new markets. The result was the Scramble for Africa, the aggressive competition for territory between Britain and her European competitors which occurred in the 1880s.

1900–1945

By 1900, the United States and Germany had experienced industrialisation on a scale comparable to that achieved in the United Kingdom and were also developing large-scale manufacturing companies; Britain's comparative economic advantage had lessened. The City of London remained the financial and commercial capital of the world, until challenged by New York after 1918.

1900–1914

The Edwardian era (1901–1910) stands out as a period of peace and plenty. There were no severe depressions and prosperity was widespread. Britain's growth rate, manufacturing output, and GDP (but not GDP per capita) fell behind its rivals the United States, and Germany. Nevertheless, the nation still led the world in trade, finance and shipping, and had strong bases in manufacturing and mining. Growth in the mining sector was strong and the coal industry played a significant role as the focus of the world's energy market; this prominence was to be challenged after the First World War by the growth of the oil industry and continuing development of the internal combustion engine. Although the relative contribution of the agricultural sector was becoming less important, productivity in the British agriculture sector was relatively high.

By international standards, and across all sectors of the United Kingdom, the British services sectors exhibited high labour factor productivity and, especially, total factor productivity; as was to be even more the case one hundred years later, it was the services sectors that provided the British economy's relative advantage in 1900.

It has been suggested that the industrial sector was slow to adjust to global changes, and that there was a striking preference for leisure over industrial entrepreneurship among the elite. In 1910, the British Empire's share of world industrial capacity stood at 15%, just behind Germany's 16%, and less than half of the United States' 35%. Despite signs of relative weakness in certain sectors of the UK economy, the major achievements of the Edwardian years should be underlined. The city was the financial centre of the world—far more efficient and wide-ranging than New York, Paris or Berlin. British investment abroad doubled in the Edwardian years, from £2 billion in 1900 to £4 billion in 1913. Britain had built up a vast reserve of overseas credits in its formal Empire, as well as in its informal empire in Latin America and other nations. The British held huge financial holdings in the United States, especially in railways. These assets proved vital in paying for supplies in the first years of the World War. Social amenities, especially in urban centres, were accumulating – prosperity was highly visible. Among the working class there was a growing demand for access to a greater say in government, but the level of industrial unrest on economic issues only became significant about 1908. In large part, it was the demands of the coal miners and railway workers, as articulated by their trade unions, that prompted a high level of strike activity in the years immediately before the First World War.

Labour Movement

The rise of a powerful, concerted, and politically effective labour movement was one of the major socio-economic phenomena of the Edwardian years in the UK. Trade union membership more than doubled during this time, from 2 million people in 1901 to 4.1 million in 1913. The Labour Party for the first time gained an active foothold in Parliament with the election of 30 Labour MPs in the 1906 General Election, enabling greater advocacy for the interests of the working classes as a whole.

Inflation and stagnating wages began in 1908, which precipitated greater discontent among the working classes, particularly as the prosperity enjoyed by the middle and upper classes was becoming ever more visible. In that year, strikes increased precipitously, mainly in the cotton and shipbuilding industries where job-cuts had occurred. In 1910, with unemployment reaching a record-low of 3 per cent, unions were emboldened by their bargaining power to make demands for higher wages and job stability. Strikes erupted throughout the nation - in the coal mining country of Wales and northeast England, the latter also experiencing a sustained railway workers' strike. In 1911 the National Transport Workers' Federation organized the first nationwide railway workers' strike, along with a general dockworker's strike in ports throughout the country. In Liverpool, the summertime strikes of the dock and transport workers culminated in a series of conflicts with the authorities between 13 and 15 August, leading to the death of two men and over 350 injured. In 1912 the National coal strike and another wave of transportation strikes cost the British economy an estimated 40 million working days.

The major demands of the labour movement during these years were wage-rises, a national minimum wage, and greater stability in employment. The Liberal government in London did make some concessions in response to the demands of organized labour, most notably with the Trade Boards Act 1909, which empowered boards to set minimum wage requirements for workers, oversee working conditions, and limit working hours. At first this applied to a very limited number of industries like lace-making and finishing, but in 1912 boards were created for the coal mining industry and within a few years all "sweated labour" occupations were overseen by such boards, guaranteeing minimum wages and safer work environments. The coal strike of 1912 was so disruptive that the British government guaranteed a minimum wage for miners with separate legislation, the Coal Mines (Minimum Wage) Act 1912.

Tariff Reform

In Edwardian Britain, proposals for more protectionist tariff policies which had begun in the 1890s became a mass political movement with high visibility. The Tariff Reform League, founded in 1903 and headed by Britain's most outspoken champion of protectionism, Joseph Chamberlain, pushed for the implementation of tariffs to protect British goods in domestic and Imperial markets. Tariff reformers like Chamberlain were worried by what was seen as a deluge of American and German products entering the domestic market; they argued that part of the reason for the success of the U.S. and German economies were the national tariffs each imposed to protect fledgling industries from foreign competition. Without tariffs, it was claimed, vulnerable young industries like electrical goods, automobiles, and chemicals would never gain traction in Britain.

A major goal of the Tariff Reform League was the foundation of an Imperial Customs Union, which would create a closed trade bloc in the British Empire and, it was hoped, fully integrate the economies of Britain and her overseas possessions. Under such an arrangement, Britain would maintain a reciprocal relationship whereby she would purchase raw materials from her colonies, the profits of which would allow them to buy finished goods from Britain, enriching both sides. Although it was a highly publicized and well-funded campaign, Tariff Reform never gained traction with the public at large. The defeat of Chamberlain's Liberal Unionist Party in the 1906 General Election, which returned a huge majority for free-trade stalwarts in the Liberal and Labour parties, was a resounding blow to the movement's electoral hopes, although the campaign itself persisted through the rest of the Edwardian period.

First World War