The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word corn in British English denoted all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The laws were designed to keep corn prices high to favour domestic farmers, and represented British mercantilism. The Corn Laws blocked the import of cheap corn, initially by simply forbidding importation below a set price, and later by imposing steep import duties, making it too expensive to import it from abroad, even when food supplies were short. The House of Commons passed the corn law bill on 10 March 1815, the House of Lords on 20 March and the bill received royal assent on 23 March 1815.

The Corn Laws enhanced the profits and political power associated with land ownership. The laws raised food prices and the costs of living for the British public, and hampered the growth of other British economic sectors, such as manufacturing, by reducing the disposable income of the British public.

The laws became the focus of opposition from urban groups who had far less political power than rural areas. The first two years of the Great Famine in Ireland of 1845–1852 forced a resolution because of the urgent need for new food supplies. The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, a Conservative, achieved repeal in 1846 with the support of the Whigs in Parliament, overcoming the opposition of most of his own party.

Economic historians see the repeal of the Corn Laws as a decisive shift toward free trade in Britain. According to one 2021 study, the repeal of the Corn Laws benefitted the bottom 90% of income earners in the United Kingdom economically, while causing income losses for the top 10% of income earners.

Origins

| Corn Act 1772 |

|---|

As a staple of life, as well as an important commodity of trade, corn and its traffic was long the subject of debate and of government regulation – the Tudors legislating against speculating in corn, and the Stuarts introducing import and export controls. Import had been regulated as early as 1670; and in 1689 traders were provided bounties for exporting rye, malt and wheat (all classified as corn at the time, the same commodities being taxed when imported into England). In 1773, "An act to regulate the importation and exportation of corn" (13 Geo. 3. c. 43) repealed Elizabethan controls on grain speculation; but also shut off exports and allowed imports when the price was above 48 shillings per quarter (thus compromising to allow for interests of producers and consumers alike). The issue however remained one of public debate (by figures such as Edmund Burke) into the 1790s; and amendments to the 1773 Act, favouring agricultural producers, were made in both 1791 and 1804.

In 1813, a House of Commons Committee recommended excluding foreign-grown corn until the price of domestically grown corn exceeded 80 shillings per quarter (8 bushels), or the equivalent in 2004 prices of around £1,102 per tonne of wheat. The political economist Thomas Malthus believed this to be a fair price, and that it would be dangerous for Britain to rely on imported corn because lower prices would reduce labourers' wages, and manufacturers would lose out due to the decrease of purchasing power of landlords and farmers.

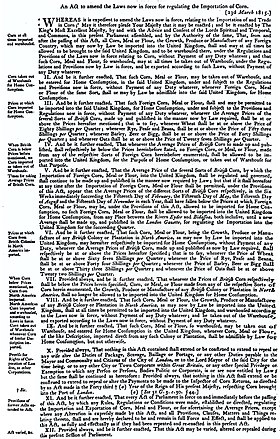

| Importation Act 1815 |

|---|

With the advent of peace when the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, corn prices decreased, and the Tory government of Lord Liverpool passed the 1815 Corn Law (officially An Act to amend the Laws now in force for regulating the Importation of Corn, or the Importation Act 1815, 55 Geo. 3. c. 26) to keep bread prices high. This resulted in serious rioting in London.

In 1816, the Year Without a Summer (caused by the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia) caused famine by disastrously reducing crop yields. Reduced standard of living and food shortages due to poor harvests led to riots. But the ceiling price of 80 shillings a quarter for domestic grain was so high that, between 1815 and 1848, it was never reached. David Ricardo, however, espoused free trade so that Britain could use its capital and population to its comparative advantage.

Opposition

In 1820, the Merchants' Petition, written by Thomas Tooke, was presented to the House of Commons. The petition demanded free trade and an end to protective tariffs. The Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, who claimed to be in favour of free trade, blocked the petition. He argued, speciously, that complicated restrictions made it difficult to repeal protectionist laws. He added, though, that he believed Britain's economic dominance grew in spite of, not because of, the protectionist system. In 1821, the President of the Board of Trade, William Huskisson, composed a Commons committee report which recommended a return to the "practically free" trade of the pre-1815 years.

| Importation Act 1822 |

|---|

| Importation of Corn Act 1828 |

|---|

The Importation Act 1822 (3 Geo. 4. c. 60) decreed that corn could be imported when the price of domestically harvested corn rose to 80/– (£4) per quarter but that the import of corn would again be prohibited when the price fell to 70/– per quarter. After this act was passed, the corn price never rose to 80/– until 1828. In 1827, the landlords rejected Huskisson's proposals for a sliding scale, and during the next year Huskisson and the new Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, devised a new sliding scale for the Importation of Corn Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4. c. 60) whereby, when domestic corn was 52/– (£2/12/–) per quarter or less, the duty would be 34/8 (£1/14/8), and when the price increased to 73/– (£3/13/–), the duty decreased to one shilling.

The Whig governments, in power for most of the years between 1830 and 1841, decided not to repeal the Corn Laws. However the Liberal Whig MP Charles Pelham Villiers proposed motions for repeal in the House of Commons every year from 1837 to 1845. In 1842, the majority against repeal was 303; by 1845 this had fallen to 132. Although he had spoken against repeal until 1845, Robert Peel voted in favour in 1846. In 1853, when Villiers was made a Privy Counsellor, The Times stated that "it was Mr Charles Villiers who practically originated the Free Trade movement".

In 1838, Villiers spoke at a meeting of 5,000 "working-class men" in Manchester. In 1840, under Villiers' direction, the Committee on Import Duties published a blue book examining the effects of the Corn Laws. Tens of thousands of copies were printed in pamphlet form by the Anti-Corn Law League, founded in 1838. The report was quoted in the major newspapers, reprinted in America, and published in an abridged form by The Spectator.

In the 1841 election, Sir Robert Peel became Prime Minister and Richard Cobden, a major proponent of free trade, was elected for the first time. Peel had studied the works of Adam Smith, David Hume and David Ricardo, and proclaimed in 1839: "I have read all that has been written by the gravest authorities on political economy on the subject of rent, wages, taxes, tithes." He voted against repeal each year from 1837 to 1845. In 1842, in response to the Blue book published by Villiers' 1840 Committee on Import Duties, Peel offered a concession by modifying the sliding scale. He reduced the maximum duty to 20/– if the price were to fall to 51/– or less. In 1842, Peel's fellow-Conservative Monckton Milnes said, at the time of this concession, that Villiers was "the solitary Robinson Crusoe sitting on the rock of Corn Law repeal".

According to historian Asa Briggs, the Anti-Corn Law League was a large, nationwide middle-class moral crusade with a Utopian vision; its leading advocate Richard Cobden promised that repeal would settle four great problems simultaneously:

First, it would guarantee the prosperity of the manufacturer by affording him outlets for his products. Second, it would relieve the Condition of England question by cheapening the price of food and ensuring more regular employment. Third, it would make English agriculture more efficient by stimulating demand for its products in urban and industrial areas. Fourth, it would introduce through mutually advantageous international trade a new era of international fellowship and peace. The only barrier to these four beneficent solutions was the ignorant self-interest of the landlords, the "bread-taxing oligarchy, unprincipled, unfeeling, rapacious and plundering."

The landlords claimed that manufacturers like Cobden wanted cheap food so that they could reduce wages and thus maximise their profits, an opinion shared by socialist Chartists. Karl Marx said: "The campaign for the abolition of the Corn Laws had begun and the workers' help was needed. The advocates of repeal therefore promised, not only a Big Loaf (which was to be doubled in size) but also the passing of the Ten Hours Bill" (to reduce working hours). In 1876, Thomas Carlyle commented on John Bright, co-founder of the League along with Cobden: "as for that party, Bright, Cobden and Co., 'Cheap and Nasty' was their watchword. It was folly to suppose good things were to be had cheap. The nation had been deluded."

The Anti-Corn Law League was agitating peacefully for repeal. They funded writers like William Cooke Taylor to travel the manufacturing regions of northern England to research their cause. Taylor published a number of books as an Anti-Corn Law propagandist, most notably, The Natural History of Society (1841), Notes of a tour in the manufacturing districts of Lancashire (1842), and Factories and the Factory System (1844). Cobden and the rest of the Anti-Corn Law League believed that cheap food meant greater real wages and Cobden praised a speech by a working man who said:

When provisions are high, the people have so much to pay for them that they have little or nothing left to buy clothes with; and when they have little to buy clothes with, there are few clothes sold; and when there are few clothes sold, there are too many to sell, they are very cheap; and when they are very cheap, there cannot be much paid for making them: and that, consequently, the manufacturing working man's wages are reduced, the mills are shut up, business is ruined, and general distress is spread through the country. But when, as now, the working man has the said 25s left in his pocket, he buys more clothing with it (ay, and other articles of comfort too), and that increases the demand for them, and the greater the demand ... makes them rise in price, and the rising price enables the working man to get higher wages and the masters better profits. This, therefore, is the way I prove that high provisions make lower wages, and cheap provisions make higher wages.

The magazine The Economist was founded in September 1843 by politician James Wilson with help from the Anti-Corn Law League; his son-in-law Walter Bagehot later became its editor.

Prelude to repeal

In February 1844, the Duke of Richmond initiated the Central Agricultural Protection Society (CAPS, commonly known as the "Anti-League") to campaign in favour of the Corn Laws.

In 1844, the agitation subsided as there were fruitful harvests. The situation changed in late 1845 with poor harvests and the Great Famine in Ireland; Britain experienced scarcity and Ireland starvation.[29] Nevertheless, Ireland continued to export substantial quantities of food to Great Britain despite its domestic privations. The problem in Ireland was not lack of food, but the price of it, which was beyond the reach of the poor. Peel argued in Cabinet that tariffs on grain should be rescinded by Order in Council until Parliament assembled to repeal the Corn Laws. His colleagues resisted this. On 22 November 1845 the Whig Leader of the Opposition Lord John Russell announced in an open letter to the electors in the City of London his support for immediate Corn Law repeal and called upon the government to take urgent action to avert famine.

The appearance of Russell's letter spurred Peel and the free-traders in his cabinet to press ahead with repeal measures over the objections of their protectionist colleagues. On 4 December 1845, an announcement appeared in The Times that the government had decided to recall Parliament in January 1846 to repeal the Corn Laws. Lord Stanley resigned from the Cabinet in protest. It quickly became clear to Peel that he would not be able to bring most of his own party with him in support of repeal and so on 11 December he resigned as Prime Minister in frustration. The Queen sent for Russell to form a government but, with the Whigs a minority in the Commons, he struggled to assemble the necessary support. Russell offered Cobden the post of Vice-President of the Board of Trade but he refused, preferring to remain an advocate of free trade outside the government. On 21 December Russell informed the Queen that he was unable to accept office. Later that same day Peel agreed to carry on as Prime Minister but, with the majority of his own party opposing his proposals, he was now dependent on the backing of the Whigs to carry repeal.

After Parliament was recalled the CAPS started a campaign of resistance. In the rural counties the CAPS was practically supplanting the local Conservative associations and in many areas the independent free holding farmers were resisting the most fiercely.

Repeal

| Importation Act 1846 |

|---|

In 1845 and 1846, the first two years of Great Famine in Ireland, there was a disastrous fall in food supplies. Prime Minister Peel called for repeal despite the opposition of most of his Conservative Party. The Anti-Corn Law League played a minor role in the passage of legislation—it had paved the way through its agitation but was now on the sidelines. On 27 January 1846, Peel gave his government's plan. He said that the Corn Laws would be abolished on 1 February 1849 after three years of gradual reductions of the tariff, leaving only a 1 shilling duty per quarter. Benjamin Disraeli and Lord George Bentinck emerged as the most forceful opponents of repeal in parliamentary debates, arguing that repeal would weaken landowners socially and politically and therefore destroy the "territorial constitution" of Britain by empowering commercial interests.

On the third reading of Peel's Bill of Repeal (Importation Act 1846) on 15 May, Members of Parliament (MPs) voted 327 votes to 229 (a majority of 98) to repeal the Corn Laws. On 25 June the Duke of Wellington persuaded the House of Lords to pass it. On that same night Peel's Irish Coercion Bill was defeated in the Commons by 292 to 219 by "a combination of Whigs, Radicals, and Tory protectionists." Peel subsequently resigned as Prime Minister. In his resignation speech he attributed the success of repeal to Cobden:

In reference to our proposing these measures, I have no wish to rob any person of the credit which is justly due to him for them. But I may say that neither the gentlemen sitting on the benches opposite, nor myself, nor the gentlemen sitting round me—I say that neither of us are the parties who are strictly entitled to the merit. There has been a combination of parties, and that combination of parties together with the influence of the Government, has led to the ultimate success of the measures. But, Sir, there is a name which ought to be associated with the success of these measures: it is not the name of the noble Lord, the member for London, neither is it my name. Sir, the name which ought to be, and which will be associated with the success of these measures is the name of a man who, acting, I believe, from pure and disinterested motives, has advocated their cause with untiring energy, and by appeals to reason, expressed by an eloquence, the more to be admired because it was unaffected and unadorned—the name which ought to be and will be associated with the success of these measures is the name of Richard Cobden. Without scruple, Sir, I attribute the success of these measures to him.

As a result, the Conservative Party divided and the Whigs formed a government with Russell as PM. Those Conservatives who were loyal to Peel were known as the Peelites and included the Earl of Aberdeen and William Ewart Gladstone. In 1859, the Peelites merged with the Whigs and the Radicals to form the Liberal Party. Disraeli became overall Conservative leader in 1868, although, when Prime Minister, he did not attempt to reintroduce protectionism.

Motivations

Scholars have advanced several explanations to resolve the puzzle of why Peel made the seemingly irrational decision to sacrifice his government to repeal the Corn Laws, a policy which he had long opposed. Lusztig (1995) argues that his actions were sensible when considered in the context of his concern for preserving aristocratic government and a limited franchise in the face of threats from popular unrest. Peel was concerned primarily with preserving the institutions of government, and he considered reform as an occasional necessary evil to preclude the possibility of much more radical or tumultuous actions. He acted to check the expansion of democracy by ameliorating conditions which could provoke democratic agitation. He also took care to ensure that the concessions would represent no threat to the British constitution.

According to Dartmouth College economic historian Douglas Irwin, Peel was influenced by economic ideas in his shift from protectionism to free trade in agriculture: "Economic ideas, and not the pressure of interests, were central to Peel's conversion to favor repeal of the Corn Laws."

Effects of repeal

The price of wheat during the two decades after 1850 averaged 52 shillings a quarter. Llewellyn Woodward argued that the high duty of corn mattered little because when British agriculture suffered from bad harvests, this was also true for foreign harvests and so the price of imported corn without the duty would not have been lower. However, the threat to British agriculture came about twenty-five years after repeal due to the development of cheaper shipping (both sail and steam), faster and thus cheaper transport by rail and steamboat, and the modernisation of agricultural machinery. The prairie farms of North America were thus able to export vast quantities of cheap grain, as were peasant farms in the Russian Empire with simpler methods but cheaper labour. Every wheat-growing country decided to increase tariffs in reaction to this, except Britain and Belgium.

In 1877, the price of British-grown wheat averaged 56/9 a quarter and for the rest of the 19th century it never reached within 10 shillings of that figure. In 1878 the price fell to 46/5. In 1886, the wheat price decreased to 31/– a quarter. By 1885, wheat-growing land declined by a million acres (4,000 km2, 281⁄2% of the previous amount) and the barley area had dwindled greatly also. Britain's dependence on imported grain during the 1830s was 2%; during the 1860s it was 24%; during the 1880s it was 45% (for wheat alone during the 1880s it was 65%). The 1881 census showed a decline of 92,250 in agricultural labourers in the ten years since 1871, with an increase of 53,496 urban labourers. Many of these had previously been farm workers who migrated to the cities to find employment, despite agricultural labourers' wages being higher than those of Europe. Agriculture's contribution to the national income was about 17% in 1871; by 1911 it was less than 7%.

Robert Ensor wrote that these years witnessed the ruin of British agriculture, "which till then had almost as conspicuously led the world, [and which] was thrown overboard in a storm like an unwanted cargo" due to "the sudden and overwhelming invasion ... by American prairie-wheat in the late seventies." Previously, agriculture had employed more people in Britain than any other industry and until 1880 it "retained a kind of headship", with its technology far ahead of most European farming, its cattle breeds superior, its cropping the most scientific and its yields the highest, with high wages leading to higher standard of living for agricultural workers than in comparable European countries. However, after 1877 wages declined and "farmers themselves sank into ever increasing embarrassments; bankruptcies and auctions followed each other; the countryside lost its most respected figures", with those who tended the land with greatest pride and conscience suffering most as the only chance of survival came in lowering standards. "For twenty years," Ensor claimed, "the only chance for any young or enterprising person on the countryside was to get out of it." The decline of agriculture also led to a fall in rural rents, especially in areas with arable land. Consequently, landowners, who until 1880 had been the richest class in the nation, were dethroned from this position. After they lost their economic leadership, the loss of their political leadership followed.

The Prime Minister at the time, Disraeli, had once been a staunch upholder of the Corn Laws and had predicted ruin for agriculture if they were repealed. However, unlike most other European governments, his government did not revive tariffs on imported cereals to save their farms and farmers. Despite calls from landowners to reintroduce the Corn Laws, Disraeli responded by saying that the issue was settled and that protection was impracticable. Ensor said that the difference between Britain and the Continent was due to the latter having conscription; rural men were thought to be the best suited as soldiers. But for Britain, with no conscript army, this did not apply. He also said that Britain staked its future on continuing to be "the workshop of the world" as the leading manufacturing nation. Robert Blake said that Disraeli was dissuaded from reviving protection due to the urban working class enjoying cheap imported food at a time of industrial depression and rising unemployment. Enfranchised by Disraeli in 1867, working men's votes were crucial in a general election and he did not want to antagonise them.

Although proficient farmers on good lands did well, farmers with mediocre skills or marginal lands were at a disadvantage. Many moved to the cities, and unprecedented numbers emigrated. Many emigrants were small under-capitalised grain farmers who were squeezed out by low prices and inability to increase production or adapt to the more complex challenge of raising livestock.

Similar patterns developed in Ireland, where cereal production was labour-intensive. The reduction of grain prices reduced the demand for agricultural labour in Ireland, and reduced the output of barley, oats, and wheat. These changes occurred at the same time that emigration was reducing the labour supply and increasing wage rates to levels too great for arable farmers to sustain.

Britain's reliance on imported food led to the danger of it being starved into submission during wartime. In 1914 Britain was dependent on imports for four-fifths of its wheat and 40% of its meat. During the First World War, the Germans in their U-boat campaign attempted to take advantage of this by sinking ships importing food into Britain, but they were eventually defeated. During the Second World War in the Battle of the Atlantic, Germany tried again to starve Britain into surrender, but again was unsuccessful.