Desires can be grouped into various types according to a few basic distinctions. Intrinsic desires concern what the subject wants for its own sake while instrumental desires are about what the subject wants for the sake of something else. Occurrent desires are either conscious or otherwise causally active, in contrast to standing desires, which exist somewhere in the back of one's mind. Propositional desires are directed at possible states of affairs while object-desires are directly about objects. Various authors distinguish between higher desires associated with spiritual or religious goals and lower desires, which are concerned with bodily or sensory pleasures. Desires play a role in many different fields. There is disagreement whether desires should be understood as practical reasons or whether we can have practical reasons without having a desire to follow them. According to fitting-attitude theories of value, an object is valuable if it is fitting to desire this object or if we ought to desire it. Desire-satisfaction theories of well-being state that a person's well-being is determined by whether that person's desires are satisfied.

Marketing and advertising companies have used psychological research on how desire is stimulated to find more effective ways to induce consumers into buying a given product or service. Techniques include creating a sense of lack in the viewer or associating the product with desirable attributes. Desire plays a key role in art. The theme of desire is at the core of romance novels, which often create drama by showing cases where human desire is impeded by social conventions, class, or cultural barriers. Melodrama films use plots that appeal to the heightened emotions of the audience by showing "crises of human emotion, failed romance or friendship", in which desire is thwarted or unrequited.

Theories

Theories of desire aim to define desires in terms of their essential features. A great variety of features are ascribed to desires, like that they are propositional attitudes, that they lead to actions, that their fulfillment tends to bring pleasure, etc. Across the different theories of desires, there is a broad agreement about what these features are. Their disagreement concerns which of these features belong to the essence of desires and which ones are merely accidental or contingent. Traditionally, the two most important theories define desires in terms of dispositions to cause actions or concerning their tendency to bring pleasure upon being fulfilled. An important alternative of more recent origin holds that desiring something means seeing the object of desire as valuable.

General features

A great variety of features is ascribed to desires. They are usually seen as attitudes toward conceivable states of affairs, often referred to as propositional attitudes. They differ from beliefs, which are also commonly seen as propositional attitudes, by their direction of fit. Both beliefs and desires are representations of the world. But while beliefs aim at truth, i.e. to represent how the world actually is, desires aim to change the world by representing how the world should be. These two modes of representation have been termed mind-to-world and world-to-mind direction of fit respectively. Desires can be either positive, in the sense that the subject wants a desirable state to be the case, or negative, in the sense that the subject wants an undesirable state not to be the case. It is usually held that desires come in varying strengths: some things are desired more strongly than other things. We desire things in regard to some features they have but usually not in regard to all of their features.

Desires are also closely related to agency: we normally try to realize our desires when acting. It is usually held that desires by themselves are not sufficient for actions: they have to be combined with beliefs. The desire to own a new mobile phone, for example, can only result in the action of ordering one online if paired with the belief that ordering it would contribute to the desire being fulfilled.he fulfillment of desires is normally experienced as pleasurable in contrast to the negative experience of failing to do so. But independently of whether the desire is fulfilled or not, there is a sense in which the desire presents its object in a favorable light, as something that appears to be good. Besides causing actions and pleasures, desires also have various effects on the mental life. One of these effects is to frequently move the subject's attention to the object of desire, specifically to its positive features. Another effect of special interest to psychology is the tendency of desires to promote reward-based learning, for example, in the form of operant conditioning.

Action-based theories

Action-based or motivational theories have traditionally been dominant. They can take different forms but they all have in common that they define desires as structures that incline us toward actions. This is especially relevant when ascribing desires, not from a first-person perspective, but from a third-person perspective. Action-based theories usually include some reference to beliefs in their definition, for example, that "to desire that P is to be disposed to bring it about that P, assuming one's beliefs are true". Despite their popularity and their usefulness for empirical investigations, action-based theories face various criticisms. These criticisms can roughly be divided into two groups. On the one hand, there are inclinations to act that are not based on desires. Evaluative beliefs about what we should do, for example, incline us toward doing it, even if we do not want to do it. There are also mental disorders that have a similar effect, like the tics associated with Tourette syndrome. On the other hand, there are desires that do not incline us toward action. These include desires for things we cannot change, for example, a mathematician's desire that the number Pi be a rational number. In some extreme cases, such desires may be very common, for example, a totally paralyzed person may have all kinds of regular desires but lacks any disposition to act due to the paralysis.

Pleasure-based theories

It is one important feature of desires that their fulfillment is pleasurable. Pleasure-based or hedonic theories use this feature as part of their definition of desires. According to one version, "to desire p is ... to be disposed to take pleasure in it seeming that p and displeasure in it seeming that not-p". Hedonic theories avoid many of the problems faced by action-based theories: they allow that other things besides desires incline us to actions and they have no problems explaining how a paralyzed person can still have desires. But they also come with new problems of their own. One is that it is usually assumed that there is a causal relation between desires and pleasure: the satisfaction of desires is seen as the cause of the resulting pleasure. But this is only possible if cause and effect are two distinct things, not if they are identical. Apart from this, there may also be bad or misleading desires whose fulfillment does not bring the pleasure they originally seemed to promise.

Value-based theories

Value-based theories are of more recent origin than action-based theories and hedonic theories. They identify desires with attitudes toward values. Cognitivist versions, sometimes referred to as desire-as-belief theses, equate desires with beliefs that something is good, thereby categorizing desires as one type of belief. But such versions face the difficulty of explaining how we can have beliefs about what we should do despite not wanting to do it. A more promising approach identifies desires not with value-beliefs but with value-seemings. On this view, to desire to have one more drink is the same as it seeming good to the subject to have one more drink. But such a seeming is compatible with the subject having the opposite belief that having one more drink would be a bad idea. A closely related theory is due to T. M. Scanlon, who holds that desires are judgments of what we have reasons to do. Critics have pointed out that value-based theories have difficulties explaining how animals, like cats or dogs, can have desires, since they arguably cannot represent things as being good in the relevant sense.

Others

A great variety of other theories of desires have been proposed. Attention-based theories take the tendency of attention to keep returning to the desired object as the defining feature of desires. Learning-based theories define desires in terms of their tendency to promote reward-based learning, for example, in the form of operant conditioning. Functionalist theories define desires in terms of the causal roles played by internal states while interpretationist theories ascribe desires to persons or animals based on what would best explain their behavior. Holistic theories combine various of the aforementioned features in their definition of desires.

Types

Desires can be grouped into various types according to a few basic distinctions. Something is desired intrinsically if the subject desires it for its own sake. Otherwise, the desire is instrumental or extrinsic. Occurrent desires are causally active while standing desires exist somewhere in the back of one's mind. Propositional desires are directed at possible states of affairs, in contrast to object-desires, which are directly about objects.

Intrinsic and instrumental

The distinction between intrinsic and instrumental or extrinsic desires is central to many issues concerning desires. Something is desired intrinsically if the subject desires it for its own sake. Pleasure is a common object of intrinsic desires. According to psychological hedonism, it is the only thing desired intrinsically. Intrinsic desires have a special status in that they do not depend on other desires. They contrast with instrumental desires, in which something is desired for the sake of something else. For example, Haruto enjoys movies, which is why he has an intrinsic desire to watch them. But in order to watch them, he has to step into his car, navigate through the traffic to the nearby cinema, wait in line, pay for the ticket, etc. He desires to do all these things as well, but only in an instrumental manner. He would not do all these things were it not for his intrinsic desire to watch the movie. It is possible to desire the same thing both intrinsically and instrumentally at the same time. So if Haruto was a driving enthusiast, he might have both an intrinsic and an instrumental desire to drive to the cinema. Instrumental desires are usually about causal means to bring the object of another desire about. Driving to the cinema, for example, is one of the causal requirements for watching the movie there. But there are also constitutive means besides causal means. Constitutive means are not causes but ways of doing something. Watching the movie while sitting in seat 13F, for example, is one way of watching the movie, but not an antecedent cause. Desires corresponding to constitutive means are sometimes termed "realizer desires".

Occurrent and standing

Occurrent desires are desires that are currently active. They are either conscious or at least have unconscious effects, for example, on the subject's reasoning or behavior. Desires we engage in and try to realize are occurrent. But we have many desires that are not relevant to our present situation and do not influence us currently. Such desires are called standing or dispositional. They exist somewhere in the back of our minds and are different from not desiring at all despite lacking causal effects at the moment. If Dhanvi is busy convincing her friend to go hiking this weekend, for example, then her desire to go hiking is occurrent. But many of her other desires, like to sell her old car or to talk with her boss about a promotion, are merely standing during this conversation. Standing desires remain part of the mind even while the subject is sound asleep. It has been questioned whether standing desires should be considered desires at all in a strict sense. One motivation for raising this doubt is that desires are attitudes toward contents but a disposition to have a certain attitude is not automatically an attitude itself. Desires can be occurrent even if they do not influence our behavior. This is the case, for example, if the agent has a conscious desire to do something but successfully resists it. This desire is occurrent because it plays some role in the agents mental life, even if it is not action-guiding.

Propositional desires and object-desires

The dominant view is that all desires are to be understood as propositional attitudes. But a contrasting view allows that at least some desires are directed not at propositions or possible states of affairs but directly at objects. This difference is also reflected on a linguistic level. Object-desires can be expressed through a direct object, for example, Louis desires an omelet. Propositional desires, on the other hand, are usually expressed through a that-clause, for example, Arielle desires that she has an omelet for breakfast. Propositionalist theories hold that direct-object-expressions are just a short form for that-clause-expressions while object-desire-theorists contend that they correspond to a different form of desire. One argument in favor of the latter position is that talk of object-desire is very common and natural in everyday language. But one important objection to this view is that object-desires lack proper conditions of satisfaction necessary for desires. Conditions of satisfaction determine under which situations a desire is satisfied. Arielle's desire is satisfied if the that-clause expressing her desire has been realized, i.e. she is having an omelet for breakfast. But Louis's desire is not satisfied by the mere existence of omelets nor by his coming into possession of an omelet at some indeterminate point in his life. So it seems that, when pressed for the details, object-desire-theorists have to resort to propositional expressions to articulate what exactly these desires entail. This threatens to collapse object-desires into propositional desires.

Higher and lower

In religion and philosophy, a distinction is sometimes made between higher and lower desires. Higher desires are commonly associated with spiritual or religious goals in contrast to lower desires, sometimes termed passions, which are concerned with bodily or sensory pleasures. This difference is closely related to John Stuart Mill's distinction between the higher pleasures of the mind and the lower pleasures of the body. In some religions, all desires are outright rejected as a negative influence on our well-being. The second Noble Truth in Buddhism, for example, states that desiring is the cause of all suffering. A related doctrine is also found in the Hindu tradition of karma yoga, which recommends that we act without a desire for the fruits of our actions, referred to as "Nishkam Karma". But other strands in Hinduism explicitly distinguish lower or bad desires for worldly things from higher or good desires for closeness or oneness with God. This distinction is found, for example, in the Bhagavad Gita or in the tradition of bhakti yoga. A similar line of thought is present in the teachings of Christianity. In the doctrine of the seven deadly sins, for example, various vices are listed, which have been defined as perverse or corrupt versions of love. Explicit reference to bad forms of desiring is found, for example, in the sins of lust, gluttony and greed. The seven sins are contrasted with the seven virtues, which include the corresponding positive counterparts. A desire for God is explicitly encouraged in various doctrines. Existentialists sometimes distinguish between authentic and inauthentic desires. Authentic desires express what the agent truly wants from deep within. An agent wants something inauthentically, on the other hand, if the agent is not fully identified with this desire, despite having it.

Roles

Desire is a quite fundamental concept. As such, it is relevant for many different fields. Various definitions and theories of other concepts have been expressed in terms of desires. Actions depend on desires and moral praiseworthiness is sometimes defined in terms of being motivated by the right desire. A popular contemporary approach defines value as that which it is fitting to desire. Desire-satisfaction theories of well-being state that a person's well-being is determined by whether that person's desires are satisfied. It has been suggested that to prefer one thing to another is just to have a stronger desire for the former thing. An influential theory of personhood holds that only entities with higher-order desires can be persons.

Action, practical reasons and morality

Desires play a central role in actions as what motivates them. It is usually held that a desire by itself is not sufficient: it has to be combined with a belief that the action in question would contribute to the fulfillment of the desire. The notion of practical reasons is closely related to motivation and desire. Some philosophers, often from a Humean tradition, simply identify an agent's desires with the practical reasons he has. A closely related view holds that desires are not reasons themselves but present reasons to the agent. A strength of these positions is that they can give a straightforward explanation of how practical reasons can act as motivation. But an important objection is that we may have reasons to do things without a desire to do them. This is especially relevant in the field of morality. Peter Singer, for example, suggests that most people living in developed countries have a moral obligation to donate a significant portion of their income to charities. Such an obligation would constitute a practical reason to act accordingly even for people who feel no desire to do so.

A closely related issue in morality asks not what reasons we have but for what reasons we act. This idea goes back to Immanuel Kant, who holds that doing the right thing is not sufficient from the moral perspective. Instead, we have to do the right thing for the right reason. He refers to this distinction as the difference between legality (Legalität), i.e. acting in accordance with outer norms, and morality (Moralität), i.e. being motivated by the right inward attitude. On this view, donating a significant portion of one's income to charities is not a moral action if the motivating desire is to improve one's reputation by convincing other people of one's wealth and generosity. Instead, from a Kantian perspective, it should be performed out of a desire to do one's duty. These issues are often discussed in contemporary philosophy under the terms of moral praiseworthiness and blameworthiness. One important position in this field is that the praiseworthiness of an action depends on the desire motivating this action.

Value and well-being

It is common in axiology to define value in relation to desire. Such approaches fall under the category of fitting-attitude theories. According to them, an object is valuable if it is fitting to desire this object or if we ought to desire it. This is sometimes expressed by saying that the object is desirable, appropriately desired or worthy of desire. Two important aspects of this type of position are that it reduces values to deontic notions, or what we ought to feel, and that it makes values dependent on human responses and attitudes. Despite their popularity, fitting-attitude theories of value face various theoretical objections. An often-cited one is the wrong kind of reason problem, which is based on the consideration that facts independent of the value of an object may affect whether this object ought to be desired. In one thought experiment, an evil demon threatens the agent to kill her family unless she desires him. In such a situation, it is fitting for the agent to desire the demon in order to save her family, despite the fact that the demon does not possess positive value.

Well-being is usually considered a special type of value: the well-being of a person is what is ultimately good for this person. Desire-satisfaction theories are among the major theories of well-being. They state that a person's well-being is determined by whether that person's desires are satisfied: the higher the number of satisfied desires, the higher the well-being. One problem for some versions of desire theory is that not all desires are good: some desires may even have terrible consequences for the agent. Desire theorists have tried to avoid this objection by holding that what matters are not actual desires but the desires the agent would have if she was fully informed.

Preferences

Desires and preferences are two closely related notions: they are both conative states that determine our behavior. The difference between the two is that desires are directed at one object while preferences concern a comparison between two alternatives, of which one is preferred to the other. The focus on preferences instead of desires is very common in the field of decision theory. It has been argued that desire is the more fundamental notion and that preferences are to be defined in terms of desires. For this to work, desire has to be understood as involving a degree or intensity. Given this assumption, a preference can be defined as a comparison of two desires. That Nadia prefers tea over coffee, for example, just means that her desire for tea is stronger than her desire for coffee. One argument for this approach is due to considerations of parsimony: a great number of preferences can be derived from a very small number of desires. One objection to this theory is that our introspective access is much more immediate in cases of preferences than in cases of desires. So it is usually much easier for us to know which of two options we prefer than to know the degree with which we desire a particular object. This consideration has been used to suggest that maybe preference, and not desire, is the more fundamental notion.

Persons, personhood and higher-order desires

Personhood is what persons have. There are various theories about what constitutes personhood. Most agree that being a person has to do with having certain mental abilities and is connected to having a certain moral and legal status. An influential theory of persons is due to Harry Frankfurt. He defines persons in terms of higher-order desires. Many of the desires we have, like the desire to have ice cream or to take a vacation, are first-order desires. Higher-order desires, on the other hand, are desires about other desires. They are most prominent in cases where a person has a desire he does not want to have. A recovering addict, for example, may have both a first-order desire to take drugs and a second-order desire of not following this first-order desire. Or a religious ascetic may still have sexual desires while at the same time wanting to be free of these desires. According to Frankfurt, having second-order volitions, i.e. second-order desires about which first-order desires are followed, is the mark of personhood. It is a form of caring about oneself, of being concerned with who one is and what one does. Not all entities with a mind have higher-order volitions. Frankfurt terms them "wantons" in contrast to "persons". On his view, animals and maybe also some human beings are wantons.

Formation

Both psychology and philosophy are interested in where desires come from or how they form. An important distinction for this investigation is between intrinsic desires, i.e. what the subject wants for its own sake, and instrumental desires, i.e. what the subject wants for the sake of something else. Instrumental desires depend for their formation and existence on other desires. For example, Aisha has a desire to find a charging station at the airport. This desire is instrumental because it is based on another desire: to keep her mobile phone from dying. Without the latter desire, the former would not have come into existence. As an additional requirement, a possibly unconscious belief or judgment is necessary to the effect that the fulfillment of the instrumental desire would somehow contribute to the fulfillment of the desire it is based on. Instrumental desires usually pass away after the desires they are based on cease to exist. But defective cases are possible where, often due to absentmindedness, the instrumental desire remains. Such cases are sometimes termed "motivational inertia". Something like this might be the case when the agent finds himself with a desire to go to the kitchen, only to realize upon arriving that he does not know what he wants there.

Intrinsic desires, on the other hand, do not depend on other desires. Some authors hold that all or at least some intrinsic desires are inborn or innate, for example, desires for pleasure or for nutrition. But other authors suggest that even these relatively basic desires may depend to some extent on experience: before we can desire a pleasurable object, we have to learn, through a hedonic experience of this object for example, that it is pleasurable. But it is also conceivable that reason by itself generates intrinsic desires. On this view, reasoning to the conclusion that it would be rational to have a certain intrinsic desire causes the subject to have this desire. It has also been proposed that instrumental desires may be transformed into intrinsic desires under the right conditions. This could be possible through processes of reward-based learning. The idea is that whatever reliably predicts the fulfillment of intrinsic desires may itself become the object of an intrinsic desire. So a baby may initially only instrumentally desire its mother because of the warmth, hugs and milk she provides. But over time, this instrumental desire may become an intrinsic desire.

The death-of-desire thesis holds that desires cannot continue to exist once their object is realized. This would mean that an agent cannot desire to have something if he believes that he already has it. One objection to the death-of-desire thesis comes from the fact that our preferences usually do not change upon desire-satisfaction. So if Samuel prefers to wear dry clothes rather than wet clothes, he would continue to hold this preference even after having come home from a rainy day and having changed his clothes. This would indicate against the death-of-desire thesis that no change on the level of the agent's conative states takes place.

Philosophy

In philosophy, desire has been identified as a philosophical problem since Antiquity. In The Republic, Plato argues that individual desires must be postponed in the name of the higher ideal. In De Anima, Aristotle claims that desire is implicated in animal interactions and the propensity of animals to motion; at the same time, he acknowledges that reasoning also interacts with desire.

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) proposed the concept of psychological hedonism, which asserts that the "fundamental motivation of all human action is the desire for pleasure." Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) had a view which contrasted with Hobbes, in that "he saw natural desires as a form of bondage" that are not chosen by a person of their own free will. David Hume (1711–1776) claimed that desires and passions are non-cognitive, automatic bodily responses, and he argued that reasoning is "capable only of devising means to ends set by [bodily] desire".

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) called any action based on desires a hypothetical imperative, which means they are a command of reason, applying only if one desires the goal in question. Kant also established a relation between the beautiful and pleasure in Critique of Judgment. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel claimed that "self-consciousness is desire".

Because desire can cause humans to become obsessed and embittered, it has been called one of the causes of woe for mankind.

Religion

Buddhism

In Buddhism, craving (see taṇhā) is thought to be the cause of all suffering that one experiences in human existence. The eradication of craving leads one to ultimate happiness, or Nirvana. However, desire for wholesome things is seen as liberating and enhancing. While the stream of desire for sense-pleasures must be cut eventually, a practitioner on the path to liberation is encouraged by the Buddha to "generate desire" for the fostering of skillful qualities and the abandoning of unskillful ones.

For an individual to effect his or her liberation, the flow of sense-desire must be cut completely; however, while training, he or she must work with motivational processes based on skillfully applied desire. According to the early Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha stated that monks should "generate desire" for the sake of fostering skillful qualities and abandoning unskillful ones.

Christianity

Within Christianity, desire is seen as something that can either lead a person towards God or away from him. Desire is not considered to be a bad thing in and of itself; rather, it is a powerful force within the human that, once submitted to the Lordship of Christ, can become a tool for good, for advancement, and for abundant living.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, the Rig Veda's creation myth Nasadiya Sukta states regarding the one (ekam) spirit: "In the beginning there was Desire (kama) that was first seed of mind. Poets found the bond of being in non-being in their heart's thought".

Psychology

Neuropsychology

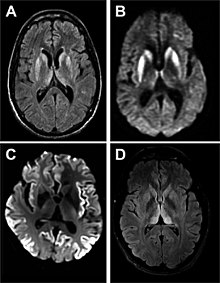

While desires are often classified as emotions by laypersons, psychologists often describe desires as ur-emotions, or feelings that do not quite fit the category of basic emotions. For psychologists, desires arise from bodily structures and functions (e.g., the stomach needing food and the blood needing oxygen). On the other hand, emotions arise from a person's mental state. A 2008 study by the University of Michigan indicated that, while humans experience desire and fear as psychological opposites, they share the same brain circuit. A 2008 study entitled "The Neural Correlates of Desire" showed that the human brain categorizes stimuli according to its desirability by activating three different brain areas: the superior orbitofrontal cortex, the mid-cingulate cortex, and the anterior cingulate cortex.

In affective neuroscience, "desire" and "wanting" are operationally defined as motivational salience; the form of "desire" or "wanting" associated with a rewarding stimulus (i.e., a stimulus which acts as a positive reinforcer, such as palatable food, an attractive mate, or an addictive drug) is called "incentive salience" and research has demonstrated that incentive salience, the sensation of pleasure, and positive reinforcement are all derived from neuronal activity within the reward system. Studies have shown that dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens shell and endogenous opioid signaling in the ventral pallidum are at least partially responsible for mediating an individual's desire (i.e., incentive salience) for a rewarding stimulus and the subjective perception of pleasure derived from experiencing or "consuming" a rewarding stimulus (e.g., pleasure derived from eating palatable food, sexual pleasure from intercourse with an attractive mate, or euphoria from using an addictive drug). Research also shows that the orbitofrontal cortex has connections to both the opioid and dopamine systems, and stimulating this cortex is associated with subjective reports of pleasure.

Psychoanalysis

Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, who is best known for his theories of the unconscious mind and the defense mechanism of repression and for creating the clinical practice of psychoanalysis, proposed the notion of the Oedipus complex, which argues that desire for the mother creates neuroses in their sons. Freud used the Greek myth of Oedipus to argue that people desire incest and must repress that desire. He claimed that children pass through several stages, including a stage in which they fixate on the mother as a sexual object. That this "complex" is universal has long since been disputed. Even if it were true, that would not explain those neuroses in daughters, but only in sons. While it is true that sexual confusion can be aberrative in a few cases, there is no credible evidence to suggest that it is a universal scenario. While Freud was correct in labeling the various symptoms behind most compulsions, phobias and disorders, he was largely incorrect in his theories regarding the etiology of what he identified.

French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan (1901–1981) argues that desire first occurs during a "mirror phase" of a baby's development, when the baby sees an image of wholeness in a mirror which gives them a desire for that being. As a person matures, Lacan claims that they still feel separated from themselves by language, which is incomplete, and so a person continually strives to become whole. He uses the term "jouissance" to refer to the lost object or feeling of absence (see manque) which a person believes to be unobtainable. Gilles Deleuze rejects the idea, defended by Lacan and other psychoanalysts, that desire is a form of lack related to incompleteness or a lost object. Instead, he holds that it should be understood as a positive reality in the form of an affirmative vital force.

Marketing

In the field of marketing, desire is the human appetite for a given object of attention. Desire for a product is stimulated by advertising, which attempts to give buyers a sense of lack or wanting. In store retailing, merchants attempt to increase the desire of the buyer by showcasing the product attractively, in the case of clothes or jewellery, or, for food stores, by offering samples. With print, TV, and radio advertising, desire is created by giving the potential buyer a sense of lacking ("Are you still driving that old car?") or by associating the product with desirable attributes, either by showing a celebrity using or wearing the product, or by giving the product a "halo effect" by showing attractive models with the product. Nike's "Just Do It" ads for sports shoes are appealing to consumers' desires for self-betterment.

In some cases, the potential buyer already has the desire for the product before they enter the store, as in the case of a decorating buff entering their favorite furniture store. The role of the salespeople in these cases is simply to guide the customer towards making a choice; they do not have to try to "sell" the general idea of making a purchase, because the customer already wants the products. In other cases, the potential buyer does not have a desire for the product or service, and so the company has to create the sense of desire. An example of this situation is for life insurance. Most young adults are not thinking about dying, so they are not naturally thinking about how they need to have accidental death insurance. Life insurance companies, though, are attempting to create a desire for life insurance with advertising that shows pictures of children and asks "If anything happens to you, who will pay for the children's upkeep?".

Marketing theorists call desire the third stage in the hierarchy of effects, which occurs when the buyer develops a sense that if they felt the need for the type of product in question, the advertised product is what would quench their desire.

Artworks

Texts

The theme of desire is at the core of the written fictions, especially romance novels. Novels which are based around the theme of desire, which can range from a long aching feeling to an unstoppable torrent, include Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert; Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez; Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov; Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, and Dracula by Bram Stoker. Brontë's characterization of Jane Eyre depicts her as torn by an inner conflict between reason and desire, because "customs" and "conventionalities" stand in the way of her romantic desires. E.M. Forster's novels use homoerotic codes to describe same-sex desire and longing. Close male friendships with subtle homoerotic undercurrents occur in every novel, which subverts the conventional, heterosexual plot of the novels. In the Gothic-themed Dracula, Stoker depicts the theme of desire which is coupled with fear. When the character Lucy is seduced by Dracula, she describes her sensations in the graveyard as a mixture of fear and blissful emotion.

Poet W. B. Yeats depicts the positive and negative aspects of desire in his poems such as "The Rose for the World", "Adam's Curse", "No Second Troy", "All Things can Tempt me", and "Meditations in Time of Civil War". Some poems depict desire as a poison for the soul; Yeats worked through his desire for his beloved, Maud Gonne, and realized that "Our longing, our craving, our thirsting for something other than Reality is what dissatisfies us". In "The Rose for the World", he admires her beauty, but feels pain because he cannot be with her. In the poem "No Second Troy", Yeats overflows with anger and bitterness because of their unrequited love. Poet T. S. Eliot dealt with the themes of desire and homoeroticism in his poetry, prose and drama. Other poems on the theme of desire include John Donne's poem "To His Mistress Going to Bed", Carol Ann Duffy's longings in "Warming Her Pearls"; Ted Hughes' "Lovesong" about the savage intensity of desire; and Wendy Cope's humorous poem "Song".

Philippe Borgeaud's novels analyse how emotions such as erotic desire and seduction are connected to fear and wrath by examining cases where people are worried about issues of impurity, sin, and shame.

Films

Just as desire is central to the written fiction genre of romance, it is the central theme of melodrama films, which are a subgenre of the drama film. Like drama, a melodrama depends mostly on in-depth character development, interaction, and highly emotional themes. Melodramatic films tend to use plots that appeal to the heightened emotions of the audience. Melodramatic plots often deal with "crises of human emotion, failed romance or friendship, strained familial situations, tragedy, illness, neuroses, or emotional and physical hardship." Film critics sometimes use the term "pejoratively to connote an unrealistic, bathos-filled, campy tale of romance or domestic situations with stereotypical characters (often including a central female character) that would directly appeal to feminine audiences." Also called "women's movies", "weepies", tearjerkers, or "chick flicks".

"Melodrama… is Hollywood's fairly consistent way of treating desire and subject identity", as can be seen in well-known films such as Gone with the Wind, in which "desire is the driving force for both Scarlett and the hero, Rhett". Scarlett desires love, money, the attention of men, and the vision of being a virtuous "true lady". Rhett Butler desires to be with Scarlett, which builds to a burning longing that is ultimately his undoing, because Scarlett keeps refusing his advances; when she finally confesses her secret desire, Rhett is worn out and his longing is spent.

In Cathy Cupitt's article on "Desire and Vision in Blade Runner", she argues that film, as a "visual narrative form, plays with the voyeuristic desires of its audience". Focusing on the dystopian 1980s science fiction film Blade Runner, she calls the film an "Object of Visual Desire", in which it plays to an "expectation of an audience's delight in visual texture, with the 'retro-fitted' spectacle of the post-modern city to ogle" and with the use of the "motif of the 'eye'". In the film, "desire is a key motivating influence on the narrative of the film, both in the 'real world', and within the text."