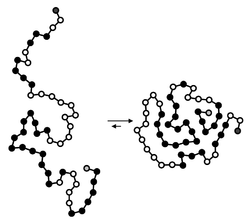

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein, after synthesis by a ribosome as a linear chain of amino acids, changes from an unstable random coil into a more ordered three-dimensional structure. This structure permits the protein to become biologically functional or active.

The folding of many proteins begins even during the translation of the polypeptide chain. The amino acids interact with each other to produce a well-defined three-dimensional structure, known as the protein's native state. This structure is determined by the amino-acid sequence or primary structure.

The correct three-dimensional structure is essential to function, although some parts of functional proteins may remain unfolded, indicating that protein dynamics are important. Failure to fold into a native structure generally produces inactive proteins, but in some instances, misfolded proteins have modified or toxic functionality. Several neurodegenerative and other diseases are believed to result from the accumulation of amyloid fibrils formed by misfolded proteins, the infectious varieties of which are known as prions. Many allergies are caused by the incorrect folding of some proteins because the immune system does not produce the antibodies for certain protein structures.

Denaturation of proteins is a process of transition from a folded to an unfolded state. It happens in cooking, burns, proteinopathies, and other contexts. Residual structure present, if any, in the supposedly unfolded state may form a folding initiation site and guide the subsequent folding reactions.

The duration of the folding process varies dramatically depending on the protein of interest. When studied outside the cell, the slowest folding proteins require many minutes or hours to fold, primarily due to proline isomerization, and must pass through a number of intermediate states, like checkpoints, before the process is complete. On the other hand, very small single-domain proteins with lengths of up to a hundred amino acids typically fold in a single step. Time scales of milliseconds are the norm, and the fastest known protein folding reactions are complete within a few microseconds. The folding time scale of a protein depends on its size, contact order, and circuit topology.

Understanding and simulating the protein folding process has been an important challenge for computational biology since the late 1960s.

Process of protein folding

Primary structure

The primary structure of a protein, its linear amino-acid sequence, determines its native conformation. The specific amino acid residues and their position in the polypeptide chain are the determining factors for which portions of the protein fold closely together and form its three-dimensional conformation. The amino acid composition is not as important as the sequence. The essential fact of folding, however, remains that the amino acid sequence of each protein contains the information that specifies both the native structure and the pathway to attain that state. This is not to say that nearly identical amino acid sequences always fold similarly. Conformations differ based on environmental factors as well; similar proteins fold differently based on where they are found.

Secondary structure

Formation of a secondary structure is the first step in the folding process that a protein takes to assume its native structure. Characteristic of secondary structure are the structures known as alpha helices and beta sheets that fold rapidly because they are stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds, as was first characterized by Linus Pauling. Formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds provides another important contribution to protein stability. α-helices are formed by hydrogen bonding of the backbone to form a spiral shape (refer to figure on the right). The β pleated sheet is a structure that forms with the backbone bending over itself to form the hydrogen bonds (as displayed in the figure to the left). The hydrogen bonds are between the amide hydrogen and carbonyl oxygen of the peptide bond. There exists anti-parallel β pleated sheets and parallel β pleated sheets where the stability of the hydrogen bonds is stronger in the anti-parallel β sheet as it hydrogen bonds with the ideal 180 degree angle compared to the slanted hydrogen bonds formed by parallel sheets.

Tertiary structure

The α-Helices and β-Sheets are commonly amphipathic, meaning they have a hydrophilic and a hydrophobic portion. This ability helps in forming tertiary structure of a protein in which folding occurs so that the hydrophilic sides are facing the aqueous environment surrounding the protein and the hydrophobic sides are facing the hydrophobic core of the protein. Secondary structure hierarchically gives way to tertiary structure formation. Once the protein's tertiary structure is formed and stabilized by the hydrophobic interactions, there may also be covalent bonding in the form of disulfide bridges formed between two cysteine residues. These non-covalent and covalent contacts take a specific topological arrangement in a native structure of a protein. Tertiary structure of a protein involves a single polypeptide chain; however, additional interactions of folded polypeptide chains give rise to quaternary structure formation.

Quaternary structure

Tertiary structure may give way to the formation of quaternary structure in some proteins, which usually involves the "assembly" or "coassembly" of subunits that have already folded; in other words, multiple polypeptide chains could interact to form a fully functional quaternary protein.

Driving forces of protein folding

Folding is a spontaneous process that is mainly guided by hydrophobic interactions, formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and it is opposed by conformational entropy. The folding time scale of an isolated protein depends on its size, contact order, and circuit topology. Inside cells, the process of folding often begins co-translationally, so that the N-terminus of the protein begins to fold while the C-terminal portion of the protein is still being synthesized by the ribosome; however, a protein molecule may fold spontaneously during or after biosynthesis. While these macromolecules may be regarded as "folding themselves", the process also depends on the solvent (water or lipid bilayer), the concentration of salts, the pH, the temperature, the possible presence of cofactors and of molecular chaperones.

Proteins will have limitations on their folding abilities by the restricted bending angles or conformations that are possible. These allowable angles of protein folding are described with a two-dimensional plot known as the Ramachandran plot, depicted with psi and phi angles of allowable rotation.

Hydrophobic effect

Protein folding must be thermodynamically favorable within a cell in order for it to be a spontaneous reaction. Since it is known that protein folding is a spontaneous reaction, then it must assume a negative Gibbs free energy value. Gibbs free energy in protein folding is directly related to enthalpy and entropy. For a negative delta G to arise and for protein folding to become thermodynamically favorable, then either enthalpy, entropy, or both terms must be favorable.

Minimizing the number of hydrophobic side-chains exposed to water is an important driving force behind the folding process. The hydrophobic effect is the phenomenon in which the hydrophobic chains of a protein collapse into the core of the protein (away from the hydrophilic environment). In an aqueous environment, the water molecules tend to aggregate around the hydrophobic regions or side chains of the protein, creating water shells of ordered water molecules. An ordering of water molecules around a hydrophobic region increases order in a system and therefore contributes a negative change in entropy (less entropy in the system). The water molecules are fixed in these water cages which drives the hydrophobic collapse, or the inward folding of the hydrophobic groups. The hydrophobic collapse introduces entropy back to the system via the breaking of the water cages which frees the ordered water molecules. The multitude of hydrophobic groups interacting within the core of the globular folded protein contributes a significant amount to protein stability after folding, because of the vastly accumulated van der Waals forces (specifically London Dispersion forces). The hydrophobic effect exists as a driving force in thermodynamics only if there is the presence of an aqueous medium with an amphiphilic molecule containing a large hydrophobic region. The strength of hydrogen bonds depends on their environment; thus, H-bonds enveloped in a hydrophobic core contribute more than H-bonds exposed to the aqueous environment to the stability of the native state.

In proteins with globular folds, hydrophobic amino acids tend to be interspersed along the primary sequence, rather than randomly distributed or clustered together. However, proteins that have recently been born de novo, which tend to be intrinsically disordered, show the opposite pattern of hydrophobic amino acid clustering along the primary sequence.

Chaperones

Molecular chaperones are a class of proteins that aid in the correct folding of other proteins in vivo. Chaperones exist in all cellular compartments and interact with the polypeptide chain in order to allow the native three-dimensional conformation of the protein to form; however, chaperones themselves are not included in the final structure of the protein they are assisting in. Chaperones may assist in folding even when the nascent polypeptide is being synthesized by the ribosome. Molecular chaperones operate by binding to stabilize an otherwise unstable structure of a protein in its folding pathway, but chaperones do not contain the necessary information to know the correct native structure of the protein they are aiding; rather, chaperones work by preventing incorrect folding conformations. In this way, chaperones do not actually increase the rate of individual steps involved in the folding pathway toward the native structure; instead, they work by reducing possible unwanted aggregations of the polypeptide chain that might otherwise slow down the search for the proper intermediate and they provide a more efficient pathway for the polypeptide chain to assume the correct conformations. Chaperones are not to be confused with folding catalyst proteins, which catalyze chemical reactions responsible for slow steps in folding pathways. Examples of folding catalysts are protein disulfide isomerases and peptidyl-prolyl isomerases that may be involved in formation of disulfide bonds or interconversion between cis and trans stereoisomers of peptide group. Chaperones are shown to be critical in the process of protein folding in vivo because they provide the protein with the aid needed to assume its proper alignments and conformations efficiently enough to become "biologically relevant". This means that the polypeptide chain could theoretically fold into its native structure without the aid of chaperones, as demonstrated by protein folding experiments conducted in vitro; however, this process proves to be too inefficient or too slow to exist in biological systems; therefore, chaperones are necessary for protein folding in vivo. Along with its role in aiding native structure formation, chaperones are shown to be involved in various roles such as protein transport, degradation, and even allow denatured proteins exposed to certain external denaturant factors an opportunity to refold into their correct native structures.

A fully denatured protein lacks both tertiary and secondary structure, and exists as a so-called random coil. Under certain conditions some proteins can refold; however, in many cases, denaturation is irreversible. Cells sometimes protect their proteins against the denaturing influence of heat with enzymes known as heat shock proteins (a type of chaperone), which assist other proteins both in folding and in remaining folded. Heat shock proteins have been found in all species examined, from bacteria to humans, suggesting that they evolved very early and have an important function. Some proteins never fold in cells at all except with the assistance of chaperones which either isolate individual proteins so that their folding is not interrupted by interactions with other proteins or help to unfold misfolded proteins, allowing them to refold into the correct native structure. This function is crucial to prevent the risk of precipitation into insoluble amorphous aggregates. The external factors involved in protein denaturation or disruption of the native state include temperature, external fields (electric, magnetic), molecular crowding, and even the limitation of space (i.e. confinement), which can have a big influence on the folding of proteins. High concentrations of solutes, extremes of pH, mechanical forces, and the presence of chemical denaturants can contribute to protein denaturation, as well. These individual factors are categorized together as stresses. Chaperones are shown to exist in increasing concentrations during times of cellular stress and help the proper folding of emerging proteins as well as denatured or misfolded ones.

Under some conditions proteins will not fold into their biochemically functional forms. Temperatures above or below the range that cells tend to live in will cause thermally unstable proteins to unfold or denature (this is why boiling makes an egg white turn opaque). Protein thermal stability is far from constant, however; for example, hyperthermophilic bacteria have been found that grow at temperatures as high as 122 °C, which of course requires that their full complement of vital proteins and protein assemblies be stable at that temperature or above.

The bacterium E. coli is the host for bacteriophage T4, and the phage encoded gp31 protein (P17313) appears to be structurally and functionally homologous to E. coli chaperone protein GroES and able to substitute for it in the assembly of bacteriophage T4 virus particles during infection. Like GroES, gp31 forms a stable complex with GroEL chaperonin that is absolutely necessary for the folding and assembly in vivo of the bacteriophage T4 major capsid protein gp23.

Fold switching

Some proteins have multiple native structures, and change their fold based on some external factors. For example, the KaiB protein switches fold throughout the day, acting as a clock for cyanobacteria. It has been estimated that around 0.5–4% of PDB (Protein Data Bank) proteins switch folds.

Protein misfolding and neurodegenerative disease

A protein is considered to be misfolded if it cannot achieve its normal native state. This can be due to mutations in the amino acid sequence or a disruption of the normal folding process by external factors. The misfolded protein typically contains β-sheets that are organized in a supramolecular arrangement known as a cross-β structure. These β-sheet-rich assemblies are very stable, very insoluble, and generally resistant to proteolysis. The structural stability of these fibrillar assemblies is caused by extensive interactions between the protein monomers, formed by backbone hydrogen bonds between their β-strands. The misfolding of proteins can trigger the further misfolding and accumulation of other proteins into aggregates or oligomers. The increased levels of aggregated proteins in the cell leads to formation of amyloid-like structures which can cause degenerative disorders and cell death. The amyloids are fibrillary structures that contain intermolecular hydrogen bonds which are highly insoluble and made from converted protein aggregates. Therefore, the proteasome pathway may not be efficient enough to degrade the misfolded proteins prior to aggregation. Misfolded proteins can interact with one another and form structured aggregates and gain toxicity through intermolecular interactions.

Aggregated proteins are associated with prion-related illnesses such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease), amyloid-related illnesses such as Alzheimer's disease and familial amyloid cardiomyopathy or polyneuropathy, as well as intracellular aggregation diseases such as Huntington's and Parkinson's disease. These age onset degenerative diseases are associated with the aggregation of misfolded proteins into insoluble, extracellular aggregates and/or intracellular inclusions including cross-β amyloid fibrils. It is not completely clear whether the aggregates are the cause or merely a reflection of the loss of protein homeostasis, the balance between synthesis, folding, aggregation and protein turnover. Recently the European Medicines Agency approved the use of Tafamidis or Vyndaqel (a kinetic stabilizer of tetrameric transthyretin) for the treatment of transthyretin amyloid diseases. This suggests that the process of amyloid fibril formation (and not the fibrils themselves) causes the degeneration of post-mitotic tissue in human amyloid diseases. Misfolding and excessive degradation instead of folding and function leads to a number of proteopathy diseases such as antitrypsin-associated emphysema, cystic fibrosis and the lysosomal storage diseases, where loss of function is the origin of the disorder. While protein replacement therapy has historically been used to correct the latter disorders, an emerging approach is to use pharmaceutical chaperones to fold mutated proteins to render them functional.

Experimental techniques for studying protein folding

While inferences about protein folding can be made through mutation studies, typically, experimental techniques for studying protein folding rely on the gradual unfolding or folding of proteins and observing conformational changes using standard non-crystallographic techniques.

X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is one of the more efficient and important methods for attempting to decipher the three dimensional configuration of a folded protein. To be able to conduct X-ray crystallography, the protein under investigation must be located inside a crystal lattice. To place a protein inside a crystal lattice, one must have a suitable solvent for crystallization, obtain a pure protein at supersaturated levels in solution, and precipitate the crystals in solution. Once a protein is crystallized, X-ray beams can be concentrated through the crystal lattice which would diffract the beams or shoot them outwards in various directions. These exiting beams are correlated to the specific three-dimensional configuration of the protein enclosed within. The X-rays specifically interact with the electron clouds surrounding the individual atoms within the protein crystal lattice and produce a discernible diffraction pattern. Only by relating the electron density clouds with the amplitude of the X-rays can this pattern be read and lead to assumptions of the phases or phase angles involved that complicate this method. Without the relation established through a mathematical basis known as Fourier transform, the "phase problem" would render predicting the diffraction patterns very difficult. Emerging methods like multiple isomorphous replacement use the presence of a heavy metal ion to diffract the X-rays into a more predictable manner, reducing the number of variables involved and resolving the phase problem.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectroscopy is a highly sensitive method for studying the folding state of proteins. Three amino acids, phenylalanine (Phe), tyrosine (Tyr) and tryptophan (Trp), have intrinsic fluorescence properties, but only Tyr and Trp are used experimentally because their quantum yields are high enough to give good fluorescence signals. Both Trp and Tyr are excited by a wavelength of 280 nm, whereas only Trp is excited by a wavelength of 295 nm. Because of their aromatic character, Trp and Tyr residues are often found fully or partially buried in the hydrophobic core of proteins, at the interface between two protein domains, or at the interface between subunits of oligomeric proteins. In this apolar environment, they have high quantum yields and therefore high fluorescence intensities. Upon disruption of the protein's tertiary or quaternary structure, these side chains become more exposed to the hydrophilic environment of the solvent, and their quantum yields decrease, leading to low fluorescence intensities. For Trp residues, the wavelength of their maximal fluorescence emission also depend on their environment.

Fluorescence spectroscopy can be used to characterize the equilibrium unfolding of proteins by measuring the variation in the intensity of fluorescence emission or in the wavelength of maximal emission as functions of a denaturant value. The denaturant can be a chemical molecule (urea, guanidinium hydrochloride), temperature, pH, pressure, etc. The equilibrium between the different but discrete protein states, i.e. native state, intermediate states, unfolded state, depends on the denaturant value; therefore, the global fluorescence signal of their equilibrium mixture also depends on this value. One thus obtains a profile relating the global protein signal to the denaturant value. The profile of equilibrium unfolding may enable one to detect and identify intermediates of unfolding. General equations have been developed by Hugues Bedouelle to obtain the thermodynamic parameters that characterize the unfolding equilibria for homomeric or heteromeric proteins, up to trimers and potentially tetramers, from such profiles. Fluorescence spectroscopy can be combined with fast-mixing devices such as stopped flow, to measure protein folding kinetics, generate a chevron plot and derive a Phi value analysis.

Circular dichroism

Circular dichroism is one of the most general and basic tools to study protein folding. Circular dichroism spectroscopy measures the absorption of circularly polarized light. In proteins, structures such as alpha helices and beta sheets are chiral, and thus absorb such light. The absorption of this light acts as a marker of the degree of foldedness of the protein ensemble. This technique has been used to measure equilibrium unfolding of the protein by measuring the change in this absorption as a function of denaturant concentration or temperature. A denaturant melt measures the free energy of unfolding as well as the protein's m value, or denaturant dependence. A temperature melt measures the denaturation temperature (Tm) of the protein. As for fluorescence spectroscopy, circular-dichroism spectroscopy can be combined with fast-mixing devices such as stopped flow to measure protein folding kinetics and to generate chevron plots.

Vibrational circular dichroism of proteins

The more recent developments of vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) techniques for proteins, currently involving Fourier transform (FT) instruments, provide powerful means for determining protein conformations in solution even for very large protein molecules. Such VCD studies of proteins can be combined with X-ray diffraction data for protein crystals, FT-IR data for protein solutions in heavy water (D2O), or quantum computations.

Protein nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Protein nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is able to collect protein structural data by inducing a magnet field through samples of concentrated protein. In NMR, depending on the chemical environment, certain nuclei will absorb specific radio-frequencies. Because protein structural changes operate on a time scale from ns to ms, NMR is especially equipped to study intermediate structures in timescales of ps to s. Some of the main techniques for studying proteins structure and non-folding protein structural changes include COSY, TOCSY, HSQC, time relaxation (T1 & T2), and NOE. NOE is especially useful because magnetization transfers can be observed between spatially proximal hydrogens are observed. Different NMR experiments have varying degrees of timescale sensitivity that are appropriate for different protein structural changes. NOE can pick up bond vibrations or side chain rotations, however, NOE is too sensitive to pick up protein folding because it occurs at larger timescale.

Because protein folding takes place in about 50 to 3000 s−1 CPMG Relaxation dispersion and chemical exchange saturation transfer have become some of the primary techniques for NMR analysis of folding. In addition, both techniques are used to uncover excited intermediate states in the protein folding landscape. To do this, CPMG Relaxation dispersion takes advantage of the spin echo phenomenon. This technique exposes the target nuclei to a 90 pulse followed by one or more 180 pulses. As the nuclei refocus, a broad distribution indicates the target nuclei is involved in an intermediate excited state. By looking at Relaxation dispersion plots the data collect information on the thermodynamics and kinetics between the excited and ground. Saturation Transfer measures changes in signal from the ground state as excited states become perturbed. It uses weak radio frequency irradiation to saturate the excited state of a particular nuclei which transfers its saturation to the ground state. This signal is amplified by decreasing the magnetization (and the signal) of the ground state.

The main limitations in NMR is that its resolution decreases with proteins that are larger than 25 kDa and is not as detailed as X-ray crystallography. Additionally, protein NMR analysis is quite difficult and can propose multiple solutions from the same NMR spectrum.

In a study focused on the folding of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis involved protein SOD1, excited intermediates were studied with relaxation dispersion and Saturation transfer. SOD1 had been previously tied to many disease causing mutants which were assumed to be involved in protein aggregation, however the mechanism was still unknown. By using Relaxation Dispersion and Saturation Transfer experiments many excited intermediate states were uncovered misfolding in the SOD1 mutants.

Dual-polarization interferometry

Dual polarisation interferometry is a surface-based technique for measuring the optical properties of molecular layers. When used to characterize protein folding, it measures the conformation by determining the overall size of a monolayer of the protein and its density in real time at sub-Angstrom resolution, although real-time measurement of the kinetics of protein folding are limited to processes that occur slower than ~10 Hz. Similar to circular dichroism, the stimulus for folding can be a denaturant or temperature.

Studies of folding with high time resolution

The study of protein folding has been greatly advanced in recent years by the development of fast, time-resolved techniques. Experimenters rapidly trigger the folding of a sample of unfolded protein and observe the resulting dynamics. Fast techniques in use include neutron scattering, ultrafast mixing of solutions, photochemical methods, and laser temperature jump spectroscopy. Among the many scientists who have contributed to the development of these techniques are Jeremy Cook, Heinrich Roder, Terry Oas, Harry Gray, Martin Gruebele, Brian Dyer, William Eaton, Sheena Radford, Chris Dobson, Alan Fersht, Bengt Nölting and Lars Konermann.

Proteolysis

Proteolysis is routinely used to probe the fraction unfolded under a wide range of solution conditions (e.g. fast parallel proteolysis (FASTpp).

Single-molecule force spectroscopy

Single molecule techniques such as optical tweezers and AFM have been used to understand protein folding mechanisms of isolated proteins as well as proteins with chaperones. Optical tweezers have been used to stretch single protein molecules from their C- and N-termini and unfold them to allow study of the subsequent refolding. The technique allows one to measure folding rates at single-molecule level; for example, optical tweezers have been recently applied to study folding and unfolding of proteins involved in blood coagulation. von Willebrand factor (vWF) is a protein with an essential role in blood clot formation process. It discovered – using single molecule optical tweezers measurement – that calcium-bound vWF acts as a shear force sensor in the blood. Shear force leads to unfolding of the A2 domain of vWF, whose refolding rate is dramatically enhanced in the presence of calcium. Recently, it was also shown that the simple src SH3 domain accesses multiple unfolding pathways under force.

Biotin painting

Biotin painting enables condition-specific cellular snapshots of (un)folded proteins. Biotin 'painting' shows a bias towards predicted Intrinsically disordered proteins.

Computational studies of protein folding

Computational studies of protein folding includes three main aspects related to the prediction of protein stability, kinetics, and structure. A 2013 review summarizes the available computational methods for protein folding.

Levinthal's paradox

In 1969, Cyrus Levinthal noted that, because of the very large number of degrees of freedom in an unfolded polypeptide chain, the molecule has an astronomical number of possible conformations. An estimate of 3300 or 10143 was made in one of his papers. Levinthal's paradox is a thought experiment based on the observation that if a protein were folded by sequential sampling of all possible conformations, it would take an astronomical amount of time to do so, even if the conformations were sampled at a rapid rate (on the nanosecond or picosecond scale). Based upon the observation that proteins fold much faster than this, Levinthal then proposed that a random conformational search does not occur, and the protein must, therefore, fold through a series of meta-stable intermediate states.

Energy landscape of protein folding

The configuration space of a protein during folding can be visualized as an energy landscape. According to Joseph Bryngelson and Peter Wolynes, proteins follow the principle of minimal frustration, meaning that naturally evolved proteins have optimized their folding energy landscapes, and that nature has chosen amino acid sequences so that the folded state of the protein is sufficiently stable. In addition, the acquisition of the folded state had to become a sufficiently fast process. Even though nature has reduced the level of frustration in proteins, some degree of it remains up to now as can be observed in the presence of local minima in the energy landscape of proteins.

A consequence of these evolutionarily selected sequences is that proteins are generally thought to have globally "funneled energy landscapes" (a term coined by José Onuchic) that are largely directed toward the native state. This "folding funnel" landscape allows the protein to fold to the native state through any of a large number of pathways and intermediates, rather than being restricted to a single mechanism. The theory is supported by both computational simulations of model proteins and experimental studies, and it has been used to improve methods for protein structure prediction and design. The description of protein folding by the leveling free-energy landscape is also consistent with the 2nd law of thermodynamics. Physically, thinking of landscapes in terms of visualizable potential or total energy surfaces simply with maxima, saddle points, minima, and funnels, rather like geographic landscapes, is perhaps a little misleading. The relevant description is really a high-dimensional phase space in which manifolds might take a variety of more complicated topological forms.

The unfolded polypeptide chain begins at the top of the funnel where it may assume the largest number of unfolded variations and is in its highest energy state. Energy landscapes such as these indicate that there are a large number of initial possibilities, but only a single native state is possible; however, it does not reveal the numerous folding pathways that are possible. A different molecule of the same exact protein may be able to follow marginally different folding pathways, seeking different lower energy intermediates, as long as the same native structure is reached. Different pathways may have different frequencies of utilization depending on the thermodynamic favorability of each pathway. This means that if one pathway is found to be more thermodynamically favorable than another, it is likely to be used more frequently in the pursuit of the native structure. As the protein begins to fold and assume its various conformations, it always seeks a more thermodynamically favorable structure than before and thus continues through the energy funnel. Formation of secondary structures is a strong indication of increased stability within the protein, and only one combination of secondary structures assumed by the polypeptide backbone will have the lowest energy and therefore be present in the native state of the protein. Among the first structures to form once the polypeptide begins to fold are alpha helices and beta turns, where alpha helices can form in as little as 100 nanoseconds and beta turns in 1 microsecond.

There exists a saddle point in the energy funnel landscape where the transition state for a particular protein is found. The transition state in the energy funnel diagram is the conformation that must be assumed by every molecule of that protein if the protein wishes to finally assume the native structure. No protein may assume the native structure without first passing through the transition state. The transition state can be referred to as a variant or premature form of the native state rather than just another intermediary step. The folding of the transition state is shown to be rate-determining, and even though it exists in a higher energy state than the native fold, it greatly resembles the native structure. Within the transition state, there exists a nucleus around which the protein is able to fold, formed by a process referred to as "nucleation condensation" where the structure begins to collapse onto the nucleus.

Modeling of protein folding

De novo or ab initio techniques for computational protein structure prediction can be used for simulating various aspects of protein folding. Molecular dynamics (MD) was used in simulations of protein folding and dynamics in silico. First equilibrium folding simulations were done using implicit solvent model and umbrella sampling. Because of computational cost, ab initio MD folding simulations with explicit water are limited to peptides and small proteins. MD simulations of larger proteins remain restricted to dynamics of the experimental structure or its high-temperature unfolding. Long-time folding processes (beyond about 1 millisecond), like folding of larger proteins (>150 residues) can be accessed using coarse-grained models.

Several large-scale computational projects, such as Rosetta@home, Folding@home and Foldit, target protein folding.

Long continuous-trajectory simulations have been performed on Anton, a massively parallel supercomputer designed and built around custom ASICs and interconnects by D. E. Shaw Research. The longest published result of a simulation performed using Anton as of 2011 was a 2.936 millisecond simulation of NTL9 at 355 K. Such simulations are currently able to unfold and refold small proteins (<150 amino acids residues) in equilibrium and predict how mutations affect folding kinetics and stability.

In 2020 a team of researchers that used AlphaFold, an artificial intelligence (AI) protein structure prediction program developed by DeepMind placed first in CASP, a long-standing structure prediction contest. The team achieved a level of accuracy much higher than any other group. It scored above 90% for around two-thirds of the proteins in CASP's global distance test (GDT), a test that measures the degree of similarity between the structure predicted by a computational program, and the empirical structure determined experimentally in a lab. A score of 100 is considered a complete match, within the distance cutoff used for calculating GDT.

AlphaFold's protein structure prediction results at CASP were described as "transformational" and "astounding". Some researchers noted that the accuracy is not high enough for a third of its predictions, and that it does not reveal the physical mechanism of protein folding for the protein folding problem to be considered solved. Nevertheless, it is considered a significant achievement in computational biology and great progress towards a decades-old grand challenge of biology, predicting the structure of proteins.