Aesthetics[a] is the branch of philosophy that studies beauty, taste, and related phenomena. In a broad sense, it includes the philosophy of art, which examines the nature of art, artistic creativity, the meanings of artworks, and audience appreciation.

Aesthetic properties are features that influence the aesthetic appeal of objects. They include aesthetic values, which express positive or negative qualities, like the contrast between beauty and ugliness. Philosophers debate whether aesthetic properties have objective existence or depend on the subjective experiences of observers. According to a common view, aesthetic experiences are associated with disinterested pleasure detached from practical concerns. Taste is a subjective sensitivity to aesthetic qualities, and differences in taste can lead to disagreements about aesthetic judgments.

Artworks are artifacts or performances typically created by humans, encompassing diverse forms such as painting, music, dance, architecture, and literature. Some definitions focus on their intrinsic aesthetic qualities, while others understand art as a socially constructed category. Art interpretation and criticism seek to identify the meanings of artworks. Discussions focus on elements such as what an artwork represents, which emotions it expresses, and what the author's underlying intent was.

Diverse fields investigate aesthetic phenomena, examining their roles in ethics, religion, and everyday life as well as the psychological processes involved in aesthetic experiences. Comparative aesthetics analyzes the similarities and differences between traditions such as Western, Indian, Chinese, Islamic, and African aesthetics. Aesthetic thought has its roots in antiquity but only emerged as a distinct field of inquiry in the 18th century when philosophers systematically engaged with its foundational concepts.

Definition

Aesthetics, sometimes spelled esthetics, is the systematic study of beauty, art, and taste. As a branch of philosophy, it examines which types of aesthetic phenomena there are, how people experience them, and how objects evoke them. This field also investigates the nature of aesthetic judgments, the meaning of artworks, and the problem of art criticism. Key questions in aesthetics include "What is art?", "Can aesthetic judgments be objective?", and "How is aesthetic value related to other values?". One characterization distinguishes between three main approaches to aesthetics: the study of aesthetic concepts and judgments, the study of aesthetic experiences and other mental responses, and the study of the nature and features of aesthetic objects. In a slightly different sense, the term aesthetics can also refer to particular theories of beauty or to beautiful appearances.

Aesthetics is closely related to the philosophy of art and the two terms are often used interchangeably since both involve the philosophical study of aesthetic phenomena. One difference is that the philosophy of art focuses on art, whereas the scope of aesthetics also includes other domains, such as beauty in nature and everyday life. This leads some theorists to argue that the philosophy of art is a subfield of aesthetics. However, the precise relation between the two fields is disputed and another characterization holds that the philosophy of art is the broader discipline. This view argues that aesthetics mainly addresses aesthetic properties, while the philosophy of art also investigates non-aesthetic features of artworks, belonging to fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of language, and ethics.

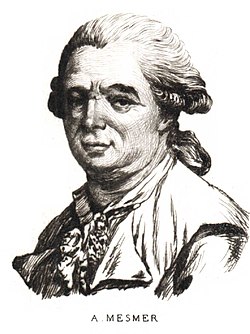

Even though the philosophical study of aesthetic problems originated in antiquity, it was not until the 18th century that aesthetics emerged as a distinct branch of philosophy when philosophers engaged in systematic inquiry into its principles. The term "aesthetics" was coined by the German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten in 1735, initially defined as the study of sensibility or sensations of beautiful objects. The term comes from the ancient Greek words aisthetikos, meaning 'perceptible things', aisthesthai, meaning 'perceive, see', and aisthesis, meaning 'sensation, perception'. The earliest known use in the English language happened in a translation by W. Hooper in the 1770s.

Basic concepts

The domain of the aesthetic encompasses a variety of properties, objects, experiences, and judgments associated with beauty and artistic expression. However, the exact boundaries of this domain are disputed—it is controversial whether there is a group of essential features shared by all aesthetic phenomena or whether they are more loosely related through family resemblances. Another central topic concerns the relation between different aesthetic concepts, for example, whether the concept "aesthetic object" is defined through the concept of "aesthetic experience".

Aesthetic properties and objects

Aesthetic properties of an object are features that shape its aesthetic appeal or factors that influence aesthetic evaluations. For instance, when an art critic describes an artwork as great, vivid, or amusing, they express aesthetic properties of this artwork. Some aesthetic properties focus on aesthetic value in general, like beautiful and ugly, while others center on more specific forms of value, such as graceful and elegant. Aesthetic properties can also refer to perceptual qualities of objects like balanced and vivid, to representational aspects like realistic and distorted, or to emotional responses such as joyful and angry.

The precise distinction between aesthetic and non-aesthetic properties is disputed. According to one proposal, aesthetic properties require a specific aesthetic sensitivity in addition to the sensory perception of non-aesthetic properties, going beyond simple colors, shapes, and sounds. Aesthetic properties are associated with evaluations, but not all are intrinsically good or bad. For example, being a realistic representation may be aesthetically good in some artistic contexts and bad in others.

The school of realism argues that aesthetic properties are objective, mind-independent features of reality. A related proposal asserts that they are emergent properties dependent on non-aesthetic properties. According to this view, the beauty of a painting may emerge from the right combination of colors and shapes. A different position holds that aesthetic properties are response-dependent, for example, that features of objects only qualify as aesthetic properties if they evoke aesthetic experiences in observers. The terms "aesthetic property" and "aesthetic quality" are often used interchangeably to refer to aspects such as beauty, sublimity, and grandeur. However, some philosophers distinguish the two, associating aesthetic properties with objective features and aesthetic qualities with subjective experiences and emotional responses.

An aesthetic object is an object with aesthetic properties. One interpretation suggests that aesthetic objects are material entities that evoke aesthetic experiences. According to this view, if a person admires an oil painting then the physical canvas and paint make up the aesthetic object. Another interpretation, associated with the school of phenomenology, argues that aesthetic objects are not material but intentional objects. Intentional objects are part of the content of experiences and their existence depends on the perceiver. An intentional object may accurately reflect a material object, as in the case of veridical perceptions, but can also fail to do so, which happens during perceptual illusions. The phenomenological perspective focuses on the intentional object given in experience rather than the material object considered independently of the perceiver.

Aesthetic values and beauty

Aesthetic values are a special type of aesthetic properties. They express the sensory appeal of an object as a qualitative measure of its aesthetic merit. Aesthetic values contrast with values in other domains, such as moral, epistemic, religious, and economic values. Beauty is usually considered the main aesthetic value, but not the only one. For example, the sublime is another value of things that inspire a feeling of awe and fear. Further suggested values include charm, elegance, harmony, and grace. Historically, pre-modern philosophers typically rejected the idea of multiple distinct aesthetic values. They tended to argue that beauty alone encompasses all that is aesthetically commendable and serves as a unifying concept of the whole domain of aesthetics. Aesthetic values are either positive, like beautiful and sublime, or negative, such as clumsy and boring. Various attempts have been made to explain why some objects have positive aesthetic values, proposing features like unity, intensity, and the right level of complexity.

The aesthetic value of beauty is often singled out as a central topic of aesthetics. It is a key aspect of human experience, influencing both personal decisions and cultural developments. Often-cited examples of beautiful objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans, and artworks. As a positive value, beauty contrasts with ugliness as its negative counterpart. Beauty is typically understood as a quality of objects that involves balance or harmony and evokes admiration or pleasure when perceived, but its precise definition is debated.

Various theoretical disputes surround the nature of beauty and its role in aesthetics. Some theories understand beauty as an objective feature of external objects. Others emphasize its subjective nature, linking it to personal experience and perception. They argue that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder" rather than in the perceived object. Another central debate concerns the features that all beautiful objects have in common. The so-called classical conception of beauty is rooted in classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. Focusing on objective features, it asserts that beauty is an harmonious arrangement of parts into a coherent whole. Aesthetic hedonism, by contrast, is a subjective theory holding that a thing is beautiful if it acts as a source of aesthetic pleasure. Other conceptions define beautiful objects in terms of intrinsic value, the manifestation of ideal forms, or as what evokes love and passion.

Aesthetic experiences, attitude, and pleasure

An aesthetic experience is an appreciation of beauty or an awareness of other aesthetic features. In its most typical form, it is a sensory perception of a natural object or an artwork. However, it can also take other forms, such as aesthetic imagination of fictional objects described in literature. Internalist theories, like Monroe Beardsley's view, explain aesthetic experience from a first-person perspective, focusing on aspects internal to the experience, such as focus and intensity. By contrast, externalist theories, such as George Dickie's position, argue that the key element of aesthetic experiences comes from the experienced external objects and their aesthetic properties.

Diverse features are associated with aesthetic experiences, but it is controversial whether any of them are essential. Aesthetic experiences usually appreciate an object for its own sake because of its sensory properties, resulting in aesthetic pleasure from a positive evaluation of the object. This pleasure is typically said to be detached from practical concerns and can involve selfless absorption, allowing imaginative freedom or free play of mental faculties in addition to sensory perception. Some theorists associate this free play with an absence of conceptual activity. Aesthetic experiences may also be normative, meaning that certain responses are appropriate, like the positive appreciation of beauty, but others are not, such as the positive appreciation of ugliness.

A central aspect of aesthetic experience is the aesthetic attitude—a special way of observing or engaging with art and nature. This attitude involves a form of pure appreciation of perceptual qualities detached from personal desires and practical concerns. It is disinterested in this sense by engaging with an object for its own sake without ulterior motives or practical consequences. For example, the experience of a violent storm through the aesthetic attitude may focus on its intricate patterns of lightning and thunder rather than preparing for its immediate dangers. One characterization understands the aesthetic attitude as a natural form of apprehension that occurs on its own in certain situations. Another outlook holds that the aesthetic attitude is a voluntary stance people can choose to adopt towards any object. There is debate about the extent and type of emotional engagement a disinterested stance requires, for instance, whether fear during a horror movie can be disinterested.

The aesthetic attitude is sometimes contrasted with other attitudes, such as the practical attitude, which is interested in usefulness and seeks to utilize or manipulate objects to achieve specific goals. Similarly, it differs from the scientific attitude, which aims to explain phenomena and acquire factual knowledge about the world. Some philosophers, such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Martin Heidegger, suggest that the aesthetic attitude can reveal aspects of reality obscured in other attitudes.

Aesthetic experience is further associated with aesthetic pleasure—a form of enjoyment in response to natural and artistic beauty. It is typically characterized as disinterested pleasure. It contrasts with interested pleasure that arises from the satisfaction of desires, such as the joy of achieving a personal goal or indulging in a particular type of food one craved. Another difference is that aesthetic pleasure does not depend on the existence of the enjoyed object, like enjoying the beauty of a sunset in a dream. The joy in achieving a personal goal, by contrast, would be frustrated if one discovered that the achievement was merely a dream. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant argue that aesthetic pleasure is pre-conceptual, meaning that it arises from a free interplay between imagination and understanding rather than from cognitive judgments or conceptual analysis. Some theorists distinguish refined from unrefined aesthetic pleasures based on whether the pleasure is evoked by a cultivated taste or an immediate, instinctual response.

Aesthetic pleasure is central to the characterization of various aesthetic phenomena, which are said to involve or evoke such pleasure. However, the view that aesthetic pleasure is the defining characteristic of the entire aesthetic domain is controversial. It faces challenges in explaining phenomena such as the sublime, drama, tragedy, and various forms of modern art, which may evoke diverse emotions not primarily linked to pleasure.

Aesthetic judgments and taste

Aesthetic judgments are assessments of the aesthetic features and values of objects, expressed in statements like "this music is beautiful". They can apply both to natural objects and artworks. Aesthetic judgments also include assessments about how or why an object has aesthetic value without explicitly determine its overall aesthetic worth, as in the statement "this music is balanced". Many debates in aesthetics concern the nature of aesthetic judgments, in particular, whether they can be as objective and universal as empirical judgments made by natural scientists. Subjectivists argue that aesthetic judgments express personal feelings and dislikes without universal validity. This view is contested by objectivists, who hold that aesthetic judgments describe objective features that are independent of the particular preferences of the judging individual. Intermediate views suggest that the standards of aesthetic judgment are grounded in stable shared dispositions rather than variable individual preferences, resulting in a form of subjective universality. This position is reflected in Kant's view, which identifies four core features of aesthetic judgments: they are subjective, universal, disinterested, and involve an interplay of sense, imagination, and understanding.

Philosophers such as Francis Hutcheson and David Hume argue that there are general aesthetic principles or universal criteria that are applied when making aesthetic judgments. Particularists, by contrast, assert that the unique nature of each aesthetic object requires a case-by-case evaluation that cannot be fully subsumed under general principles. A related debate between rationalism and the immediacy thesis concerns whether aesthetic judgments are mediated through concept application and reasoning or emerge directly from sensory intuition.

Aesthetic judgments rely on taste, which is a sensitivity to aesthetic qualities, a capacity to feel aesthetic pleasure, or an ability to discern beauty and other aesthetic qualities. Taste is a type of preference expressed in immediate reactions and is sometimes understood as an inner sense or cognitive faculty. Differences in taste are often used to explain why people disagree about aesthetic judgments and why the judgments of some people, such as art critics with extensive experience and a refined sense, carry more weight than those of casual observers. Taste varies both between cultures and between individuals within a culture.[e] However, there are also some cross-cultural agreements. Various philosophers argue that taste can be learned to some extent and that the judgments of experienced observers follow similar standards, suggesting the existence of social norms of right and wrong aesthetic assessments.

The term "aesthetic universal" refers to aspects of taste and other aesthetic phenomena that are shared across different cultures and societies, indicating common features of human nature underlying aesthetics. Suggested general tendencies include the dispositions to engage in artistic expressions or to derive aesthetic pleasure from appreciating these expressions. The existence of more specific shared tendencies is debated. An example is the idea that humans generally find savanna-like landscapes with open grassy plains and scattered trees pleasing.

Art

Art is a central topic of aesthetics and the main subject of the philosophy of art. It encompasses diverse forms, including painting, sculpture, music, dance, literature, and theater. This field covers both artworks and the skills or activities involved in their creation. Artworks are artifacts or performances typically created by humans. They differ in this respect from naturally occurring aesthetic objects, like landscapes and sunsets.

Definitions

A central debate in the philosophy of art concerns the definition of art or how to distinguish it from non-art. There are diverse theories, each offering a unique perspective about the nature of art.

Essentialist approaches argue that there is an essence or a set of inherent features shared by all artworks and only by them. They often define artworks in terms of other aesthetic concepts, such as representation, beauty, or aesthetic experience. An early object-centered approach, first proposed by Plato, characterizes artworks as representations that seek to reflect or imitate certain aspects of reality. Another definition suggests that artworks are objects designed to evoke aesthetic experiences or pleasure. A related approach proposes that all artworks have certain aesthetic properties in common, such as beauty. Aesthetic formalism argues that specific formal features, such as a "significant form", are the hallmark of art. Artist-centered approaches see artistic activity as the essential aspect of artworks. One conception understands artworks as special vehicles through which artists express emotions and other mental states.

Conventionalist definitions view art as a socially constructed category. This means that it does not primarily depend on the inherent properties of objects, for example, what they represent or what forms they have. Instead, art is defined by social and cultural agreements, which are subject to change. A key motivation for this approach has been the emergence of modern art, which has challenged many earlier conceptions. Conventionalist definitions can explain, for instance, that even mundane ready-made objects like a urinal are considered art if conventions say so. Institutional theories argue that the conventions are set by social institutions of the art world. Because of this social dependence, an object considered art in one society may not be art in another society. Historical theories, another form of conventionalism, assert that the category of art depends on established traditions and historical contexts. They claim that an object becomes part of this category if it stands in the right relation to these traditions, for example, by being created in an artistic context and resembling other recognized artworks.

There are also hybrid theories that combine elements from other theories. For instance, one approach holds that an object is an artwork if it either meets certain aesthetic standards or is conventionally regarded as art. The diversity of proposed definitions and the difficulties in reconciling them have led some philosophers to argue against the existence of precise criteria. Some conclude that a definition is strictly impossible. Others provide vague characterizations, suggesting that the domain of art is characterized by overlapping similarities, known as family resemblance.

Ontology and categories

The ontology of art seeks to discern the fundamental categories of being to which all artworks belong. Universalists argue that artworks are universals—general or repeatable entities that can have several instances at the same time. For example, a novel can have many copies, a film can have many screenings, and a photo can have many prints. One version of this view distinguishes artworks as types from their instances, which are considered tokens of this type. Particularists reject the idea that artworks are universals, arguing instead that they are particulars or unique concrete entities. For them, if there are several instances then the artwork is the collection or sum of all instances. According to this view, Alfred Stieglitz's photograph The Steerage is not a type underlying its prints but rather the collection or sum of all prints together.

A similar discussion addresses whether artworks are material objects, which exist independent of observers, or intentional objects, which exist in the experience of observers. Pluralists argue that different types of artworks belong to distinct ontological categories. Contextualists accept this view and further propose that the ontological category depends on the context of discussion. Deflationism is skeptical about the fundamental existence of artworks in any form. It acknowledges that the term art may be practically useful in everyday language but rejects that it refers to any fundamental entities of reality.

Artworks are categorized in various ways. Some distinctions focus on the medium used to express artistic ideas. For example, paintings typically use paint, such as oil or acryl paint, which is distributed on a surface, whereas dance involves bodily movements. Similarly, music is performed using instruments and voice to produce sounds, and literature relies on language. Hybrid forms like opera and film combine several of these elements. Another distinction is between performance works and object works. Performance works, like a song performed on stage, are dynamically enacted in time, whereas object works, like a painting, have a more static nature. Artworks can also be classified by style, such as impressionism and surrealism, and by their intended purpose, like political and religious art.

Meaning

The meaning of an artwork is what is involved in understanding it or comprehending what it communicates, encompassing factors such as representation and expression. Certain aspects of meaning may be directly accessible while others require in-depth interpretation, for example, to grasp symbolic or metaphorical elements. Understanding influences aesthetic experience and for certain artworks, a comprehensive understanding may be required to fully appreciate them. One approach to the analysis of meaning is the distinction between form and content. Content refers to what is presented, such as the depicted topic, expressed ideas, and conceptual messages. Form refers to how the content is presented, such as medium, technique, composition, and style. Form encompasses diverse modes of presentation in different art forms, like color and spatial arrangement in painting, harmony and rhythm in music, and narrative voice and plot structure in literature.

Representation and expression

Representation is a depiction of real or imagined entities. For example, a portrait painting represents a person, while a fantasy novel represents an imaginary chain of events. Similarity is a crucial element in many forms of artistic representation, meaning that the artwork resembles the depicted entity. However, representation can also happen through other means, such as conventional symbols and established codes. It is particularly prevalent in some art forms and styles, such as classical art and realism. Since antiquity, representation has been a key concept in theories of art, such as Plato's idea of defining art as imitation. However, it is controversial whether representation plays a central role in all art forms, including music and abstract modern art.

Expression is the conveyance of psychological states, such as emotions, moods, and attitudes. For example, a painter may depict a barren landscape in muted colors to express sadness, while a musician might use a fast tempo and upbeat melody to convey excitement. The expressed mental states often align with the artist's personal experience. However, this is not necessarily the case and artists may explore psychological states they observed in others or entirely fictional experiences. An artwork can express a mental state like sadness by evoking it in the experience of the audience. Alternatively, the expression can also happen if observers recognize the presence of sadness in the artwork even if they do not personally feel it. Expression theories consider expression a core feature of artworks. They characterize artworks as expressions of the artist's mind, focusing on creativity and originality in the manifestation of aesthetic experiences.

Interpretation and criticism

The process of interpretation is the attempt to uncover the meaning of an artwork to understand its significance and value. In the widest sense, interpretation encompasses any way of assigning meaning, including obvious descriptions of depicted entities and explanations of literal word meanings. In philosophy of art, the term is typically used in a more narrow sense for assignments of meaning that involve deeper analysis and creative thought. Interpretations aim to discover underlying aspects that are relevant to the understanding and appreciation of the artwork. The terms interpretation and criticism are sometimes used interchangeably. However, criticism is typically associated with more components, like a general description of the criticized artwork and a classification of style and genre. Criticism also explains the art-historical background and evaluates positive and negative qualities.

Critics sometimes propose conflicting interpretations of the same artwork. According to critical monism, there is only one comprehensive correct interpretation, implying that conflicting interpretations cannot both be correct. Critical pluralism, by contrast, asserts that there can be different but equally valid interpretations and that it is not always possible to determine which of two conflicting interpretations is superior. A similar issue involves whether interpretations can be true or false in an objective sense.

Various frameworks of interpretation have been proposed. According to intentionalism, the meaning of an artwork is determined by the author's intent—their reasons and motives that led to the creation of the artwork. This typically involves analyzing the ideas the artist aimed to express but can also include a biographical analysis to learn about psychological and social circumstances in the artist's life.

Intentionalism is a controversial theory, termed intentional fallacy by its critics. Some objections point to cases where the author's intention cannot be known, where the author themselves cannot be identified, or where no traditional author exists, as artworks created by artificial intelligence. In these cases, meaning would be inaccessible or non-existent. Other objections assert that an artist may fail to accurately express their intention or may manifest unintended aesthetic features, suggesting that an artwork can contain both less and more than the artist intended.

An alternative to intentionalism argues that meaning is determined by artistic, stylistic, linguistic, and other cultural conventions. For example, linguistic conventions determine the literal meanings of words and thereby influence the overall meaning of a poem. Another framework holds that meaning is shaped by how the audience, rather than the author, interprets or would interprets the intention underlying the work. Artistic formalism proposes a different approach by focusing interpretation exclusively on formal or perceptual features of artworks.

Aestheticism and instrumentalism are theories about the value of art. Aestheticism asserts that the primary value of art lies in its intrinsic aesthetic merits, independent of any external purposes. This idea of the autonomy of art is expressed in the slogan "art for art's sake". Strong forms of aestheticism not only disregard external purposes but see them as detrimental influences that undermine artistic integrity. Instrumentalism, by contrast, explains the value of art by the effects it has on other domains. It understands art as a means to things such as moral education, spiritual growth, therapeutic benefits, and social cohesion.

The individual arts

The individual arts are diverse practices or disciplines in the domain of art. They encompass a wide range of fields, including traditionally established forms such as painting, music, and literature, as well as newer types like video games. One classification divides them into visual arts, literary arts, and performance arts. However, the boundaries between these categories are not always clear, and alternative classifications have been proposed.

Painting is a visual art in which a painter applies colors to a surface. It allows for a diverse range of motives and styles, and is often considered a paradigm form of art. The representation of real entities plays a central role in many forms of painting, ranging from landscapes and people to historic events. This process involves artistic choices that go beyond simple replication, such as guiding the viewer's attention to specific aspects or highlighting important but easily overlooked features. The issue of representation is also crucial in photography, a visual art shaped by technological developments in camera design and editing processes. A key topic in the philosophy of photography concerns its mechanical manner of authentically representing real objects, frequently drawing parallels and distinctions with painting. The status of photographs as true artworks is disputed, with critics arguing that the mechanical nature of capturing images lacks the necessary artistic creativity.

Music is a performance art in which sounds are combined to create aesthetic patterns, relying on aspects such as melody and rhythm. Unlike painting and photography, music is typically less associated with objective representation, having a closer link to the expression of emotions. A key discussion in the philosophy of music revolves around the definition of music or the criteria under which a combination of sounds is music. Proposals range from objective criteria, such as the organization of sounds, to subjective criteria, like the way sounds are interpreted or experienced. Dance is another performance art in which dancers perform a series of bodily movements, often following a choreography. It is typically accompanied by music and shares with music an emphasis on expressive features.

Architecture is the art or craft of designing and building, encompassing a wide range of structures from monuments and cathedrals to skyscrapers and residential homes. It typically combines aesthetic with functional goals, seeking to create buildings that are both visually appealing and practically useful. This dual nature is a central topic of the philosophy of architecture, with one theory suggesting that mere buildings can be distinguished from artistic architecture by the presence of decorative elements. Sculpture is another art form that, like architecture, involves the creation of three-dimensional works. Sculptures are usually static objects made of robust materials like stone, metal, and wood. However, the field of sculpture is broader and covers diverse three-dimensional objects, including kinetic sculptures. Key discussions in the philosophy of sculpture address the definition, representational aspects, and aesthetic features of sculptures as well as the influence of the chosen material.

Literature has language as its primary medium. In its widest sense, literature encompasses any written document. However, the term is typically used in a more narrow sense in aesthetics for forms of writing that belong to the high arts, such as poems, novels, and drama. Literature as an art is often characterized by its deliberate, elaborate, and organized use of language, but there is no universally accepted demarcation between artistic literature and other forms of writing. Poetry is a distinct form of literature often written in verses composed of several lines that may follow specific patterns, such as meter and rhyme. Many poems are characterized by a deliberate economical use of language that seeks to evoke specific experiences while being difficult to paraphrase.

Theater is a performance art that combines elements from other art forms. It typically includes a carefully prepared set or stage where actors perform, usually incorporating storytelling and sound design to create immersive experiences. Theater is performed before a live audience, which can create a sense of immediacy that is less prevalent in related art forms, such as film. Film also integrates aspects from various artistic disciplines but relies more heavily on technological means of recording and editing. Films can involve actors but may also include animated characters or document real-life events. They are normally the result of collaborative efforts of many people, which complicates the identification of a singular author in the traditional sense.

Video games are a more recent form of art. Like theater and film, they usually blend visual, auditory, and narrative elements. They typically stand out through their emphasis on player interaction, allowing active exploration of and engagement with the game world. The status of films and video games as serious forms of art is disputed. Proponents tend to emphasize their aesthetic qualities, while critics often point to their association with mass production and popular culture as counterarguments. For video games, a related debate centers on the elements of competition and winning, questioning whether these elements run counter to the spirit of art.

In various fields

Aesthetic phenomena are investigated in diverse fields. They cover the relation between aesthetics and other branches of philosophy, scientific inquiry using empirical methods, comparisons of different artistic traditions, and the study of aesthetic elements in specific areas of life.

Ethics

Ethics is the branch of philosophy that studies moral phenomena in general and right behavior in particular. Artworks can have various ethical consequences by influencing how people feel, perceive, and evaluate their circumstances. For example, artworks can glorify violence and reinforce biases, just as they can inspire empathy and challenge societal norms. As a result, art is also relevant to the field of politics since it can steer political sentiment to legitimize authority or mobilize resistance, thereby influencing voter attitudes. However, artworks can also explore morally relevant topics without expressing a clear positive or negative evaluation.

Since both ethics and aesthetics deal with values, philosophers seek to clarify the relation between moral and aesthetic values, proposing diverse theories of their interaction. Ethicism asserts that the moral value of an artwork can increase its aesthetic value, while ethical defects may undermine its artistic merit. This view is reversed by immoralism, which suggests that in some cases, moral flaws enhance aesthetic experience. Autonomism rejects both positions, arguing that these domains of evaluation are independent.

Psychology and related fields

Scientific approaches rooted in psychology and related fields employ empirical methods to conduct inquiries and justify hypotheses. The psychology of aesthetics examines the mental processes involved in the perception and appreciation of beauty and art, using methods such as experimentation, observation, and surveys.

Experimental aesthetics is an early and influential approach pioneered by Gustav Fechner. It follows a bottom-up methodology that starts with human sensation, investigating preferences to simple physical stimuli, such as basic colors and shapes. Gestalt psychology relies on a more holistic outlook, examining how composition and object placement influence aesthetic experience, like the relation between balanced organization and a sense of calm. Some works, such as Daniel Berlyne's approach, shift the focus from perception to emotion, suggesting that features like novelty and complexity cause arousal and that the right amount of arousal is pleasurable.

Psychological analysis also examines the temporal structure of aesthetic experiences of art. One outlook identifies two phases: an initial first impression in which the observer forms a rough general idea of the artwork's topic, structure, and meaning, followed by a focal analysis of more specific features. Research further explores how circumstances influence aesthetic experience, like the contrast between encountering a painting in a museum or a shopping mall. In addition to physical circumstances, social and personal factors also influence aesthetic experience, such as group dynamics, prior knowledge, and the motivation for seeking the experience.

Evolutionary psychology analyzes mental phenomena as products of natural selection. It asserts that genetic variations responsible for new capacities are passed on to future generations if they enhance survival and reproduction. Adopting this approach, evolutionary aesthetics interprets beauty and other aesthetic experiences as adaptive traits that serve diverse functions. Examples are aesthetic preferences for environments conducive to survival, such as landscapes resembling the African savannah, and sexual selection by identifying genetically fit mates. By focusing on the relatively permanent biological nature of humans, evolutionary psychology sees aesthetic values as universal or transcultural patterns of taste and appreciation, contrasting with theories in the philosophy of art that understand aesthetic values as cultural constructs.

Neuroaesthetics applies neuroscientific insights and methods to study the relation between brain activity and aesthetic experience. Aesthetic experiences arise from diverse brain processes responsible for organizing sensory stimuli, forming cognitive interpretations, and generating emotional responses. Neuroaesthetics examines these processes using various methods, including neuroimaging techniques like fMRI. In one type of experiment, participants view diverse artworks, some considered beautiful and others ugly. By comparing brain responses measured through neuroimaging, researchers can discern, for example, that the brain area known as the orbitofrontal cortex is more active when viewing beautiful paintings.

Cognitive science employs an interdisciplinary approach to study mental phenomena by examining how they access and transform information. An influential theory, suggested by Ernst Gombrich, analyzes aesthetic experience through the interplay of low-level and high-level information processes: human sensation provides low-level information, which is organized and interpreted using high-level conceptual background knowledge. Specific frameworks in cognitive science have also been used to analyze aesthetic phenomena. For instance, the modularity of mind—the hypothesis that the mind is composed of mental modules that function independently—has been employed to explain that paintings can represent real objects by triggering the same mental modules responsible for the recognition of real objects.

Comparative aesthetics

Comparative aesthetics examines diverse aesthetic traditions, analyzing the similarities and differences in their standards of beauty and theoretical approaches. For example, the focus in Western aesthetics on high art and its separation from everyday affairs is not common in most other traditions, for which art is typically closely integrated with practical functions in everyday life, including religion and moral education. Artistic differences between different traditions also encompass dominant media, common styles, and chosen motifs.

The comparison of cultural products from different traditions presents various conceptual challenges associated with tradition-specific aesthetic concepts and standards of evaluation. The uncritical application of standards from one tradition to evaluate the works of another can result in cultural imperialism. However, these differences also provide opportunities to artists and philosophers to incorporate new elements and explore novel perspectives.

Indian aesthetics draws a close connection between artistic activity and religious practice. It argues that artistic expression is a spiritual endeavor that should be informed by knowledge of the self and reality, express devotion to the divine, and avoid attachments to the fruits of the activity. Indian aesthetics analyzes art in terms of basic life emotions, called rasas, such as delight, humor, sadness, and anger. It sees art as a play that imitates reality by conveying experiences of the rasas. Its focus is on the universal expressions of human emotional life rather than person-specific feelings. This school of thought identifies artistic creativity as the ability to harness the full potential of the medium, like colors, sounds, and words, to convey experiential universals. For the audience, it recommends an aesthetic attitude characterized by a psychic distance from private concerns to transcend the personal self and become receptive to universal elements.

Chinese aesthetics emphasizes the spontaneous nature of artistic creativity and its connection to the moral and spiritual domains. It argues that art should foster harmony within society and align with the natural order of the universe. In this role, art is both self-expression and self-cultivation aimed to promote social well-being. The main focus of Chinese aesthetics is on poetry, painting, and calligraphy, known as the three perfections. This tradition influenced Japanese aesthetics, which is characterized by its interest in nature. Different art styles in this tradition are shaped by religious outlooks, particularly Shinto and Buddhism. Japanese theories of art stress the interrelation between the experience of the artist and the response of the audience.

Islamic philosophers see art as a means of communicating philosophical and religious truths, making them accessible to the general public without requiring abstract theoretical thought. Thinkers such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna argued that imagination rather than reasoning underlies artistic creation and appreciation. According to this view, art imitates reality and evokes emotions to convey underlying truths and positively influence behavior. Religious teachings play a central role in Islamic aesthetics. For example, the belief that Allah is transcendent and boundless has resulted in the avoidance of figurative depictions and the emphasis on abstract art forms.

African aesthetics emphasizes the intuitive and emotional nature of art, highlighting its communal function in social life. Early scholarship on this tradition was typically conducted from an ethnocentric perspective using Western aesthetic standards to interpret and evaluate African art. This usually resulted in the portrayal of African artworks as exotic curiosities that lack the sophistication of high art. The emergence of indigenous scholarship in the 20th century sought to correct this interpretation, arguing that the emphasis on moral, emotional, and intuitive aspects reflects different artistic standards rather than a deficiency. This school of thought, often associated with the concept of Négritude, focuses on the importance of feelings in contrast to abstraction and intellectual analysis.

Environment, everyday life, and religion

Environmental aesthetics deals with the appreciation of nature, including elements such as forests, mountain ranges, rivers, and flowers. It encompasses both transient appearances, such as the fleeting beauty of a landscape during sunset, and enduring aspects, such as the majesty of a centuries-old tree. This field focuses on sensory and formal qualities associated with beauty and related aesthetic qualities. It contrasts in this respect with the philosophy of art, which typically emphasizes the interpretation of underlying meanings associated with expression and representation. However, some approaches to environmental aesthetics also consider the impact of background knowledge on the aesthetic experience of nature. For instance, ecological awareness of the intricate relationships within an ecosystem can shape the appreciation of a woodland environment by understanding it as a habitat of diverse species.

In its broadest sense, environmental aesthetics encompasses the appreciation of any environment, including those created by humans. This inquiry is closely associated with everyday aesthetics, which examines aesthetic phenomena encountered in daily life. Everyday aesthetics covers both public and private environments, ranging from modern cities and industrial sites to private homes and backyards, as well as personal adornments and consumer products, such as clothing, hairstyles, industrial design, and web design. The aesthetics of popular art, a related discipline, investigates aesthetic qualities in popular culture and compares the evaluative standards of popular art with high or fine art. For example, it studies the contrast between commercial mass art and experimental avant-garde and explores specific types of popular art, such as kitsch.

Art plays a central role in the field of religion and manifests in many forms, including paintings, sculptures, architecture, music, dance, and literature. Its key characteristic comes from its religious function, such as conveying theological and moral teachings, representing symbolic truths, inspiring religious experiences, and aiding devotional practices. Religious art is part of all major religions and was the dominant art form during ancient and medieval times. However, its influence began to wane in the modern period due to secularization. This shift is also reflected in developments in the philosophy of art that introduced a focus on disinterestedness and the autonomy of aesthetic experience from external purposes, including religious goals.

Others

Various theories of aesthetics are associated with specific philosophical schools of thought. Marxist aesthetics examines the relation between art, class structure, and social ideology, exploring how art can enforce or challenge established power hierarchies. Feminist aesthetics criticizes male biases in aesthetic theory and artistic practice while exploring alternatives. It investigates unfair social institutions and aesthetic standards that disadvantage women and exclude them from the art world. An example is the male gaze—a cultural phenomenon that treats women as objects of male spectatorship rather than as artistic creators. Postmodern aesthetics is a diverse movement that challenges established concepts and theories in the field of aesthetics. It typically rejects the focus on disinterested pleasure, the autonomy of art from other domains, and the distinction between high and popular art. It tends to promote a pluralism that embraces diversity, playfulness, and irony.

The term mathematical beauty refers to aesthetic qualities of abstract mathematical concepts and theories. For instance, a mathematical proof may be considered beautiful if it demonstrates a profound insight in an effective manner or reveals an underlying unity of seemingly disparate mathematical ideas.

Computer art involves the use of computers in the creation of artworks. It can take many forms, ranging from minor digital enhancements of existing artworks to entirely new creations generated using complex algorithms. Its abstract nature based on symbolic representation and manipulation of electronic signals distinguishes computer art from traditional forms of art, which rely on more tangible media. This medium offers new artistic possibilities, such as virtual reality and interactivity. Rapid developments in artificial intelligence in the 21st century have significantly impacted computer art. They include the emergence of generative models—systems that are trained on existing media to create new texts, images, music, or videos in response to verbal descriptions of the intended result. Examples include ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, MuseNet, and RunwayML.

Meta-aesthetics examines the fundamental assumptions and concepts underlying aesthetics. It asks about the existence of aesthetic facts, the meaning of aesthetic statements, and the ways of acquiring aesthetic knowledge. A central meta-aesthetic debate between realism and anti-realism addresses whether there are mind-independent aesthetic facts. A related discussion between cognitivism and non-cognitivism considers whether aesthetic statements can be objectively true or primarily express personal emotions.

History

Ancient

Aesthetics has its roots in ancient thought, which typically interpreted beauty as a metaphysical phenomenon associated with the order of the cosmos. In ancient Greek philosophy, early explorations of the nature of beauty are found in Pythagorean philosophy in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. This tradition proposed that beauty arises from the proportion and harmony between different elements, an idea later also examined by the Stoics. Plato (427–347 BCE) analyzed pure beauty as an immutable form that exists independent of matter. He argued that material entities are beautiful if they participate in the form of beauty. Plato understood art as a craft that seeks to imitate and represent material entities. He acknowledged that art has some didactic value but was overall critical of it, asserting that its derivative nature, based on imitation of sensible features, cannot lead to true knowledge.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) examined aesthetics through the lens of poetry. He agreed with Plato's idea that art is a form of imitation but adopted a more positive outlook, proposing that it can reveal universal truths. Aristotle suggested that successful artistic imitation is pleasurable and can have therapeutic or cathartic effects. By linking this pleasure to beauty, he tried to explain why the imitation of unpleasurable phenomena, like tragic stories, can be enjoyable. Also influenced by Plato, Plotinus (204–270 CE) argued that beauty is not based on sensory symmetries or simple proportions but embodies an underlying order, harmony, and unity associated with the ultimate source of creation.

In ancient India, the Natya Shastra, traditionally attributed to Bharata (c. 200 BCE–200 CE), formulated the rasa theory of art. This theory posits that the goal of art is to convey fundamental life emotions as experiential universals of human existence. In ancient China, the philosophy of art was shaped by Confucianism. It emphasized self-cultivation and the relation between nature and human culture.

Medieval

During the medieval period, the rise of Christianity led Western aesthetic thinkers to blend ancient Greek thought with religious teachings, often in the form of philosophical theology. Influenced by Plato and Plotinus, Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) explored the distinction between artistic creation, which transforms matter, and divine creation, which brings forth existence out of nothing. He thought that all beauty originates from God and analyzed it in terms of unity, equality, number, proportion, and order. Thomas Aquinas defined beauty as what brings pleasure upon perception. For him, the mind plays a central role in this process since beauty lies in the immaterial form of the perceived object that the mind recognizes in the sensory data. Aquinas saw beauty as a basic category of being and identified it with proportion, radiance, and integrity.

An integration of Greek philosophy and religious thought also happened in the Islamic world. Al-Farabi (c. 878–950 CE) associated beauty with pleasure and saw it as a degree of perfection and a divine attribute of Allah. Avicenna (980–1037 CE) distinguished sensible from intelligible beauty and explored psychological processes underlying aesthetic judgments, such as the role of imagination.

Meanwhile in India, the rasa theory of art expanded to also encompass devotional practices, including efforts to portray or evoke profound religious experiences of the union with the divine. For example, Abhinavagupta (c. 950–1025 CE) elaborated the spiritual dimension of the rasa theory, drawing a sharp distinction between ordinary worldly emotions and rasas as transcendent aesthetic emotions.

In Chinese thought, Xie He (c. 5th to 6th centuries CE) combined Daoist and Confucian ideas, suggesting that artists align with the natural order of the universe and spontaneously express the movement of life in their artworks. He also proposed a set of basic principles of painting. Guo Xi (c. 1020–1090 CE) argued that artworks reflect the moral character and spiritual outlook of the artist, which he saw as a central factor of the artwork's aesthetic value. During this period, the growing influence of Buddhism on Chinese aesthetic thought led to an artistic shift from objective reality to subjective experiences as a result of Buddhist teachings on the illusory nature of reality.

The medieval period in the West came to an end with the emergence of the Renaissance starting in the 15th century. This change led to the revival of classical aesthetic ideals while secularization paved the way for rationalist inquiries into general laws of beauty and empiricist analyses of sensory and emotional experiences in the subsequent Age of Enlightenment.

Modern and contemporary

Modern aesthetics emerged in the 18th century as philosophers systematically engaged with its foundational concepts while carefully formulating and critiquing major positions. A key step in this process happened through the philosophy of Alexander Baumgarten (1714–1762), who first conceived aesthetics as a distinct field of inquiry: the science of sensory cognitions or the study of what is sensed and imagined. In British philosophy, Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) followed ideas of the third Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713) and provided an early theory of taste, conceptualizing it as an inner sense responsible for aesthetic apprehension. This outlook inspired David Hume (1711–1776) to develop a subjective theory of beauty, understanding it as a pleasurable sentiment caused by perceptions. He integrated this perspective with the existence of intersubjective standards of beauty as principles of taste governing which objects are experienced as beautiful.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) expanded Hume's idea that aesthetic judgments are both subjective and universally valid, arguing that the underlying pleasure must be disinterested to follow universal standards. According to Kant, this type of pleasure comes from a free play in which the mental faculties of imagination and understanding harmoniously interact. In response to earlier theories by Edmund Burke (1729–1797), Kant also examined the sublime as a distinct aesthetic quality.

Kant's thought inspired diverse developments in German philosophy. Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) saw art as a unifying phenomenon that synthesizes different basic human drives in a type of play. F. W. J. von Schelling (1775–1854) shared a similar perspective, arguing that art reconciles opposites and reveals the underlying unity of the self and nature. G. W. F. Hegel (1770–1831) explored aesthetics through his philosophical system of absolute idealism, seeing artistic beauty as the sensory manifestation of ideas. He analyzed art history from antiquity to his present day as a series of progressive stages of this manifestation.

Combining Kantian and Indian philosophy, Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) saw disinterested aesthetic experience as a suspension of the will, resulting in a temporary peace of mind by interrupting the cycle of striving and suffering. He inspired the Chinese philosopher Wang Guowei (1877–1927), who integrated Schopenhauer's ideas with Buddhist thought. Wang viewed the goal of art as the creation of worlds within the world, which are open to disinterested reflection. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) rejected the disinterestedness of aesthetic experience and the autonomy of art from other domains. Instead, he considered art an expression of the struggle between opposing life forces and saw art as a vehicle of transformation and life affirmation.

Following the thought of Karl Marx (1818–1883), Marxist aesthetic philosophers like Leon Trotsky (1879–1940) and Georg Lukács (1885–1971) examined how art reflects and shapes social ideologies and power hierarchies. Drawing from Marxist ideas, Theodor Adorno (1903–1969) critiqued the commodification of art and explored its ability to express alienation and challenge societal norms. Also adopting a Marxist perspective, Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) studied how advances in technological reproducibility transform art.

Romanticist thought, expressed in the works of J. W. von Goethe (1749–1832), William Wordsworth (1770–1850), and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), emphasized artistic originality, creativity, and the expression of profound feelings. It saw artworks as products of human genius that defy rule-based understanding. This school of thought inspired the theory of expressionism, which asserts that the primary function of art is to communicate emotions and other mental states. It was explored by thinkers such as Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), Benedetto Croce (1866–1952), and R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943). Intentionalism, a closely related position, focuses on the author's intent as the source of meaning of artworks. Monroe Beardsley (1915–1985) opposed this view, arguing that meaning is not fixed by the author's intent. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and Carl Jung (1875–1961) interpreted art through a psychoanalytic perspective as expressions of the unconscious, an approach also later explored by Richard Wollheim (1923–2005).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, aestheticism became a prominent view in English-speaking philosophy. For example, Walter Pater (1839–1894) and Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) proposed that art is an end in itself without an ulterior purpose. Pragmatists rejected this outlook and the idea that aesthetic experience is disinterested. For instance, John Dewey (1859–1952) proposed that the value of art lies in the unique experiences it provides, which can lead to individual and societal improvements. Formalism became another influential theory of art in the early 20th century. It dismisses the focus on expressive and representational aspects and argues instead that artworks are defined by formal features, like the arrangement of perceptual qualities. Clive Bell (1881–1964), a major proponent of this view, termed this arrangement "significant form".

The emergence of Dadaism and conceptual art challenged traditional definitions of art based on intrinsic features of artworks. As a result, anti-essentialism, which understands art as a social construct without an inherent essence, gained prominence in the second half of the 20th century, exemplified in the theories of Frank Sibley (1923–1996) and Nelson Goodman (1906–1998). These developments inspired Arthur C. Danto (1924–2013) and George Dickie (1926–2020) to propose institutional definitions, arguing that social conventions set by the art world determine which objects are artworks. Mary Mothersill (1923–2008) challenged these developments. She aimed to restore earlier conceptions of beauty associated with Aquinas, Hume, and Kant, focusing on the apprehension of aesthetic qualities.

In continental philosophy, the school of phenomenology explored diverse aspects of the immediate experience of art. For example, it examined how artworks can depict unreal objects, how imagination is involved in the process, and how art can reveal features of reality. This tradition is closely related to existentialist aesthetics, which views artworks as expressions of human freedom that can authentically portray central aspects of the human condition. The philosophy of Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) influenced both traditions. He criticized the focus on disinterested pleasure found in modern philosophy of art, arguing that artworks can reveal truths about human existence and provide new perspectives of understanding. Heidegger's student Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002) further explored the relation between art and truth, examining aesthetic experience and traditional theories through phenomenological analysis and hermeneutic interpretation.

Postmodern thinkers, like Roland Barthes (1915–1980) and Jacques Derrida (1930–2004), challenged the separation of art from everyday life and the idea that artworks have a stable meaning or universal value. They suggested instead that artistic merit depends on historical and cultural contexts. Starting in the 1970s, feminist perspectives in aesthetics challenged male-centric theories and practices within aesthetic philosophy and the art world. For example, Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986) and Luce Irigaray (1930–present) explored how feminine perspectives are marginalized by masculine standards.