Green politics, or ecopolitics, is a political ideology that aims to foster an ecologically sustainable society often, but not always, rooted in environmentalism, nonviolence, social justice and grassroots democracy. It began taking shape in the Western world in the 1970s; since then, green parties have developed and established themselves in many countries around the globe and have achieved some electoral success.

The political term green was used initially in relation to die Grünen (German for "the Greens"), a green party formed in the late 1970s. The term political ecology is sometimes used in academic circles, but it has come to represent an interdisciplinary field of study as the academic discipline offers wide-ranging studies integrating ecological social sciences with political economy in topics such as degradation and marginalization, environmental conflict, conservation and control and environmental identities and social movements.

Supporters of green politics share many ideas with the conservation, environmental, feminist and peace movements. In addition to democracy and ecological issues, green politics is concerned with civil liberties, social justice, nonviolence, sometimes variants of localism and tends to support social progressivism. Green party platforms are largely considered left in the political spectrum. The green ideology has connections with various other ecocentric political ideologies, including ecofeminism, eco-socialism, degrowth and green anarchism, but to what extent these can be seen as forms of green politics is a matter of debate. As the left-wing green political philosophy developed, there also came into separate existence opposite movements on the right-wing that include ecological components such as eco-capitalism and green conservatism.

History

Influences

Adherents to green politics tend to consider it to be part of a higher worldview and not simply a political ideology. Green politics draws its ethical stance from a variety of sources, from the values of indigenous peoples, to the ethics of Mahatma Gandhi, Baruch Spinoza, and Jakob von Uexküll. These people influenced green thought in their advocacy of long-term seventh generation foresight, and on the personal responsibility of every individual to make moral choices.

Unease about adverse consequences of human actions on nature predates the modern concept of environmentalism. Social commentators as far apart as ancient Rome and China complained of air, water and noise pollution.

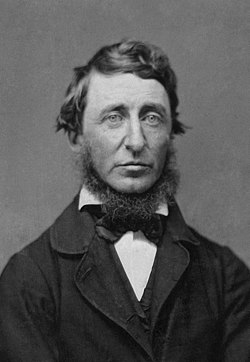

The philosophical roots of environmentalism can be traced back to enlightenment thinkers such as Rousseau in France, and later the author and naturalist Thoreau in America. Organised environmentalism began in late 19th-century Europe and the United States, as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution with its emphasis on unbridled economic expansion.

"Green politics" first began as conservation and preservation movements, such as the Sierra Club, founded in San Francisco in 1892.

Left-green platforms of the form that make up the green parties today draw terminology from the science of ecology, and policy from environmentalism, deep ecology, feminism, pacifism, anarchism, libertarian socialism, libertarian possibilism, social democracy, eco-socialism, and/or social ecology or green libertarianism. In the 1970s, as these movements grew in influence, green politics arose as a new philosophy which synthesized their goals. The Green Party political movement is not to be confused with the unrelated fact that in some far-right and fascist parties, nationalism has on occasion been tied into a sort of green politics which promotes environmentalism as a form of pride in the "motherland" according to a minority of authors.

Early development

In June 1970, a Dutch group called Kabouters won 5 of the 45 seats on the Amsterdam Gemeenteraad (City Council), as well as two seats each on councils in The Hague and Leeuwarden and one seat apiece in Arnhem, Alkmaar and Leiden. The Kabouters were an outgrowth of Provo's environmental White Plans and they proposed "Groene Plannen" ("Green Plans").

The first political party to be created with its basis in environmental issues was the United Tasmania Group, founded in Australia in March 1972 to fight against deforestation and the creation of a dam that would damage Lake Pedder; whilst it only gained three percent in state elections, it inspired the creation of Green parties all over the world. In May 1972, a meeting at Victoria University of Wellington launched the Values Party, the world's first countrywide green party to contest Parliamentary seats nationally. In November 1972, Europe's first green party, PEOPLE in the UK came into existence.

The German Green Party was not the first Green Party in Europe to have members elected nationally but the impression was created that they had been, because they attracted the most media attention: The German Greens, contended in their first national election in the 1980 federal election. They started as a provisional coalition of civic groups and political campaigns which, together, felt their interests were not expressed by the conventional parties. After contesting the 1979 European elections they held a conference which identified Four Pillars of the Green Party which all groups in the original alliance could agree as the basis of a common Party platform: welding these groups together as a single Party. This statement of principles has since been utilised by many Green Parties around the world. It was this party that first coined the term "Green" ("Grün" in German) and adopted the sunflower symbol. The term "Green" was coined by one of the founders of the German Green Party, Petra Kelly, after she visited Australia and saw the actions of the Builders Labourers Federation and their green ban actions. In the 1983 federal election, the Greens won 27 seats in the Bundestag.

Further developments

The first Canadian foray into green politics took place in the Maritimes when 11 independent candidates (including one in Montreal and one in Toronto) ran in the 1980 federal election under the banner of the Small Party. Inspired by Schumacher's Small is Beautiful, the Small Party candidates ran for the expressed purpose of putting forward an anti-nuclear platform in that election. It was not registered as an official party, but some participants in that effort went on to form the Green Party of Canada in 1983 (the Ontario Greens and British Columbia Greens were also formed that year). Green Party of Canada leader Elizabeth May was the instigator and one of the candidates of the Small Party and she was eventually elected as a member of the Green Party in 2011 Canadian federal election.

In Finland, the Green League became the first European Green Party to form part of a state-level Cabinet in 1995. The German Greens followed, forming a government with the Social Democratic Party of Germany (the "Red-Green Alliance") from 1998 to 2005. In 2001, they reached an agreement to end reliance on nuclear power in Germany, and agreed to remain in coalition and support the German government of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder in the 2001 Afghan War. This put them at odds with many Greens worldwide, but demonstrated that they were capable of difficult political tradeoffs.

In Latvia, Indulis Emsis, leader of the Green Party and part of the Union of Greens and Farmers, an alliance of a Nordic agrarian party and the Green Party, was Prime Minister of Latvia for ten months in 2004, making him the first Green politician to lead a country in the history of the world. In 2015, Emsis' party colleague, Raimonds Vējonis, was elected President of Latvia by the Latvian parliament. Vējonis became the first green head of state worldwide.

In the German state of Baden-Württenburg, the Green Party became the leader of the coalition with the Social Democrats after finishing second in the 2011 Baden-Württemberg state election. In the following state election, 2016, the Green Party became the strongest party for the first time in a German Landtag.

In 2016, the former leader of the Austrian Greens (1997 to 2008), Alexander Van der Bellen, officially running as an independent, won the 2016 Austrian presidential election, making him the second green head of state worldwide and the first directly elected by popular vote. Van der Bellen placed second in the election's first round with 21.3% of the vote, the best result for the Austrian Greens in their history. He won the second-round run-off against the far-right Freedom Party's Norbert Hofer with 53.8% of the votes, making him the first president of Austria who was not backed by either the People's Party or the Social Democratic Party.

Core tenets

According to Derek Wall, a prominent British green proponent, there are four pillars that define green politics:

In 1984, the Green Committees of Correspondence in the United States expanded the Four Pillars into Ten Key Values, which further included:

- Decentralization

- Community-based economics

- Post-patriarchal values (later translated to ecofeminism and Ethics of care)

- Respect for diversity

- Global responsibility

- Future focus

In 2001, the Global Greens were organized as an international green movement. The Global Greens Charter identified six guiding principles:

- Ecological wisdom

- Social justice

- Participatory democracy

- Nonviolence

- Sustainability

- Respect for diversity

Ecology

Economics

Green economics focuses on the importance of the health of the biosphere to human well-being. Consequently, most Greens distrust conventional capitalism, as it tends to emphasize economic growth while ignoring ecological health; the "full cost" of economic growth often includes damage to the biosphere, which is unacceptable according to green politics. Green economics considers such growth to be "uneconomic growth"— material increase that nonetheless lowers the overall quality of life. Green economics inherently takes a longer-term perspective than conventional economics, because such a loss in quality of life is often delayed. According to green economics, the present generation should not borrow from future generations, but rather attempt to achieve what Tim Jackson calls "prosperity without growth".

Some Greens refer to productivism, consumerism and scientism as "grey", as contrasted with "green", economic views. "Grey" approaches focus on behavioral changes.

Therefore, adherents to green politics advocate economic policies designed to safeguard the environment. Greens want governments to stop subsidizing companies that waste resources or pollute the natural world, subsidies that Greens refer to as "dirty subsidies". Some currents of green politics place automobile and agribusiness subsidies in this category, as they may harm human health. On the contrary, Greens look to a green tax shift that are seen to encourage both producers and consumers to make ecologically friendly choices.

Many aspects of green economics could be considered anti-globalist. According to many left-wing greens, economic globalization is considered a threat to well-being, which will replace natural environments and local cultures with a single trade economy, termed the global economic monoculture. This is not a universal policy of greens, as green liberals and green conservatives support a regulated free market economy with additional measures to advance sustainable development.

Since green economics emphasizes biospheric health and biodiversity, an issue outside the traditional left-right spectrum, different currents within green politics incorporate ideas from socialism and capitalism. Greens on the Left are often identified as eco-socialists, who merge ecology and environmentalism with socialism and Marxism and blame the capitalist system for environmental degradation, social injustice, inequality and conflict. eco-capitalists, on the other hand, believe that the free market system, with some modification, is capable of addressing ecological problems. This belief is documented in the business experiences of eco-capitalists in the book, The Gort Cloud that describes the gort cloud as the green community that supports eco-friendly businesses.

-

Tim Jackson, author of Prosperity Without Growth

-

-

-

Serge Latouche, theorist of degrowth

Participatory democracy

Since the beginning, green politics has emphasized local, grassroots-level political activity and decision-making. According to its adherents, it is crucial that citizens play a direct role in the decisions that influence their lives and their environment. Therefore, green politics seeks to increase the role of deliberative democracy, based on direct citizen involvement and consensus decision making, wherever it is feasible.

Green politics also encourages political action on the individual level, such as ethical consumerism, or buying things that are made according to environmentally ethical standards. Indeed, many green parties emphasize individual and grassroots action at the local and regional levels over electoral politics. Historically, green parties have grown at the local level, gradually gaining influence and spreading to regional or provincial politics, only entering the national arena when there is a strong network of local support.

In addition, many greens believe that governments should not levy taxes against strictly local production and trade. Some Greens advocate new ways of organizing authority to increase local control, including urban secession, bioregional democracy, and co-operative/local stakeholder ownership.

-

Michael Albert, theorist of participatory economics (participism)

-

-

Antonio Negri, theorist of Post-fordism and immaterial labour

Other issues

Although Greens in the United States "call for an end to the 'War on Drugs'" and "for the decriminalization of victimless crimes", they also call for developing "a firm approach to law enforcement that directly addresses violent crime, including trafficking in hard drugs". In Europe, some green parties have tended to support the creation of a democratic federal Europe, while others have opposed European integration.

In the spirit of nonviolence, green politics oppose the war on terrorism and the curtailment of civil rights, focusing instead on nurturing deliberative democracy in war-torn regions and the construction of a civil society with an increased role for women.

In keeping with their commitment to the preservation of diversity, greens are often committed to the maintenance and protection of indigenous communities, languages, and traditions. An example of this is the Irish Green Party's commitment to the preservation of the Irish Language. Some of the green movement has focused on divesting in fossil fuels. Academics Stand Against Poverty states "it is paradoxical for universities to remain invested in fossil fuel companies". Thomas Pogge says that the fossil fuel divestment movement can increase political pressure at events like the international climate change conference (COP). Alex Epstein of Forbes notes that it is hypocritical to ask for divestment without a boycott and that a boycott would be more effective. Some institutions that are leading by example in the academic area are Stanford University, Syracuse University, Sterling College and over 20 more. A number of cities, counties and religious institutions have also joined the movement to divest.

Green politics mostly opposes nuclear fission power and the buildup of persistent organic pollutants, supporting adherence to the precautionary principle, by which technologies are rejected unless they can be proven to not cause significant harm to the health of living things or the biosphere.

Green platforms generally favor tariffs on fossil fuels, restricting genetically modified organisms, and protections for ecoregions or communities.

The Green Party supports phasing out of nuclear power, coal, and incineration of waste. However, the Green Party in Finland has come out against its previous anti-nuclear stance and has stated that addressing global warming in the next 20 years is impossible without expanding nuclear power. These officials have proposed using nuclear-generated heat to heat buildings by replacing the use of coal and biomass to reach zero-emission outputs by 2040.

-

Naomi Klein has written about capitalism and climate.

-

Martha Nussbaum, Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago, is a proponent of the capabilities approach to animal rights.

-

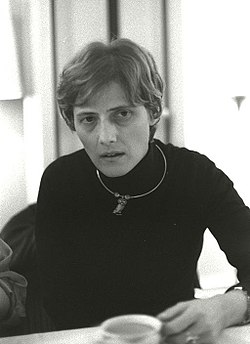

Anna Grodzka, Polish green LGBTQIA advocate

Organization

Local movements

Green ideology emphasizes participatory democracy and the principle of "thinking globally, acting locally." As such, the ideal Green Party is thought to grow from the bottom up, from neighborhood to municipal to (eco-)regional to national levels. The goal is to rule by a consensus decision making process.

Strong local coalitions are considered a prerequisite to higher-level electoral breakthroughs. Historically, the growth of Green parties has been sparked by a single issue where Greens can appeal to ordinary citizens' concerns. In Germany, for example, the Greens' early opposition to nuclear power won them their first successes in the federal elections.

Global organization

There is a growing level of global cooperation between Green parties. Global gatherings of Green Parties now happen. The first Planetary Meeting of Greens was held 30–31 May 1992, in Rio de Janeiro, immediately preceding the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held there. More than 200 Greens from 28 nations attended. The first formal Global Greens Gathering took place in Canberra, in 2001, with more than 800 Greens from 72 countries in attendance. The second Global Green Congress was held in São Paulo, Brazil, in May 2008, when 75 parties were represented.

Global Green networking dates back to 1990. Following the Planetary Meeting of Greens in Rio de Janeiro, a Global Green Steering Committee was created, consisting of two seats for each continent. In 1993 this Global Steering Committee met in Mexico City and authorized the creation of a Global Green Network including a Global Green Calendar, Global Green Bulletin, and Global Green Directory. The Directory was issued in several editions in the next years. In 1996, 69 Green Parties from around the world signed a common declaration opposing French nuclear testing in the South Pacific, the first statement of global greens on a current issue. A second statement was issued in December 1997, concerning the Kyoto climate change treaty.

At the 2001 Canberra Global Gathering delegates for Green Parties from 72 countries decided upon a Global Greens Charter which proposes six key principles. Over time, each Green Party can discuss this and organize itself to approve it, some by using it in the local press, some by translating it for their website, some by incorporating it into their manifesto, some by incorporating it into their constitution. This process is taking place gradually, with online dialogue enabling parties to say where they are up to with this process.

The Gatherings also agree on organizational matters. The first Gathering voted unanimously to set up the Global Green Network (GGN). The GGN is composed of three representatives from each Green Party. A companion organization was set up by the same resolution: Global Green Coordination (GGC). This is composed of three representatives from each Federation (Africa, Europe, The Americas, Asia/Pacific, see below). Discussion of the planned organization took place in several Green Parties prior to the Canberra meeting.[45] The GGC communicates chiefly by email. Any agreement by it has to be by unanimity of its members. It may identify possible global campaigns to propose to Green Parties worldwide. The GGC may endorse statements by individual Green Parties. For example, it endorsed a statement by the US Green Party on the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Thirdly, Global Green Gatherings are an opportunity for informal networking, from which joint campaigning may arise. For example, a campaign to protect the New Caledonian coral reef, by getting it nominated for World Heritage Status: a joint campaign by the New Caledonia Green Party, New Caledonian indigenous leaders, the French Green Party, and the Australian Greens. Another example concerns Ingrid Betancourt, the leader of the Green Party in Colombia, the Green Oxygen Party (Partido Verde Oxigeno). Ingrid Betancourt and the party's Campaign Manager, Claire Rojas, were kidnapped by a hard-line faction of FARC on 7 March 2002, while travelling in FARC-controlled territory. Betancourt had spoken at the Canberra Gathering, making many friends. As a result, Green Parties all over the world have organized, pressing their governments to bring pressure to bear. For example, Green Parties in African countries, Austria, Canada, Brazil, Peru, Mexico, France, Scotland, Sweden and other countries have launched campaigns calling for Betancourt's release. Bob Brown, the leader of the Australian Greens, went to Colombia, as did an envoy from the European Federation, Alain Lipietz, who issued a report. The four Federations of Green Parties issued a message to FARC. Ingrid Betancourt was rescued by the Colombian military in Operation Jaque in 2008.

Global Green Meetings

Separately from the Global Green Gatherings, Global Green Meetings take place. For instance, one took place on the fringe of the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. Green Parties attended from Australia, Taiwan, Korea, South Africa, Mauritius, Uganda, Cameroon, the Republic of Cyprus, Italy, France, Belgium, Germany, Finland, Sweden, Norway, the US, Mexico and Chile.

The Global Green Meeting discussed the situation of Green Parties on the African continent; heard a report from Mike Feinstein, former mayor of Santa Monica, about setting up a website of the GGN; discussed procedures for the better working of the GGC; and decided two topics on which the Global Greens could issue statements in the near future: Iraq and the 2003 WTO meeting in Cancun.

Green federations

Affiliated members in Asia, Pacific and Oceania form the Asia-Pacific Green Network. The member parties of the Global Greens are organised into four continental federations:

- Federation of Green Parties of Africa

- Federation of the Green Parties of the Americas / Federación de los Partidos Verdes de las Américas

- Asia-Pacific Green Network

- European Green Party

The European Federation of Green Parties formed itself as the European Green Party on 22 February 2004, in the run-up to European Parliament elections in June 2004, a further step in trans-national integration.