From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Photovoltaic SUDI shade is an autonomous and mobile station in France that provides energy for electric cars using solar energy.

Solar PV has specific advantages as an energy source: once installed, its operation generates no pollution and no

greenhouse gas emissions, it shows simple scalability in respect of power needs and silicon has large availability in the Earth’s crust.

PV systems have the major disadvantage that the power output

works best with direct sunlight, so about 10-25% is lost if a tracking

system is not used. Dust, clouds, and other obstructions in the atmosphere also diminish the power output.

Another important issue is the concentration of the production in the

hours corresponding to main insolation, which do not usually match the

peaks in demand in human activity cycles.

Unless current societal patterns of consumption and electrical networks

adjust to this scenario, electricity still needs to be stored for later

use or made up by other power sources, usually hydrocarbons.

Photovoltaic systems have long been used in specialized applications, and stand-alone and

grid-connected PV systems have been in use since the 1990s. They were first mass-produced in 2000, when German environmentalists and the

Eurosolar organization got government funding for a ten thousand roof program.

Advances in technology and increased manufacturing scale have in

any case reduced the cost, increased the reliability, and increased the

efficiency of photovoltaic installations.

Net metering and financial incentives, such as preferential

feed-in tariffs for solar-generated electricity, have supported solar PV installations in many countries. More than

100 countries now use solar PV.

After

hydro and

wind powers,

PV is the third renewable energy source in terms of global capacity. At

the end of 2016, worldwide installed PV capacity increased to more than

300

gigawatts (GW), covering approximately two percent of global

electricity demand.

China, followed by

Japan and the

United States, is the fastest growing market, while

Germany remains the world's largest producer, with solar PV providing seven percent of annual domestic electricity consumption. With current technology (as of 2013), photovoltaics

recoups the energy needed to manufacture them in 1.5 years in Southern Europe and 2.5 years in Northern Europe.

Etymology

The term "photovoltaic" comes from the

Greek φῶς (

phōs) meaning "light", and from "volt", the unit of electro-motive force, the

volt, which in turn comes from the last name of the

Italian physicist

Alessandro Volta, inventor of the battery (

electrochemical cell). The term "photo-voltaic" has been in use in English since 1849.

Solar cells

Photovoltaic

power potential map estimates, how much kWh of electricity can be

produced from a 1 kWp free-standing c-Si modules, optimally inclined

towards the Equator. The resulting long-term average (daily or yearly)

is calculated based on the time-series weather data of at least recent

10 years. The map is published by the World Bank and provided by

Solargis.

Photovoltaics are best known as a method for generating electric power by using

solar cells to convert energy from the sun into a flow of electrons by the

photovoltaic effect.

Solar photovoltaic power generation has long been seen as a

clean energy

technology which draws upon the planet’s most plentiful and widely

distributed renewable energy source – the sun. Cells require protection

from the environment and are usually packaged tightly in solar panels.

Photovoltaic power capacity is measured as maximum power output under standardized test conditions (STC) in "W

p" (

watts peak).

The actual power output at a particular point in time may be less than

or greater than this standardized, or "rated", value, depending on

geographical location, time of day, weather conditions, and other

factors. Solar photovoltaic array

capacity factors are typically under 25%, which is lower than many other industrial sources of electricity.

Current developments

For best performance, terrestrial PV systems aim to maximize the time they face the sun.

Solar trackers

was achieve this by moving PV panels to follow the sun. The increase

can be by as much as 20% in winter and by as much as 50% in summer.

Static mounted systems can be optimized by analysis of the

sun path.

Panels are often set to latitude tilt, an angle equal to the latitude,

but performance can be improved by adjusting the angle for summer or

winter. Generally, as with other semiconductor devices, temperatures

above room temperature reduce the performance of photovoltaics.

A number of solar panels may also be mounted vertically above each other in a tower, if the

zenith distance of the

Sun

is greater than zero, and the tower can be turned horizontally as a

whole and each panels additionally around a horizontal axis. In such a

tower the panels can follow the Sun exactly. Such a device may be

described as a

ladder mounted on a turnable disk. Each step of that ladder is the middle axis of a rectangular

solar panel.

In case the zenith distance of the Sun reaches zero, the "ladder" may

be rotated to the north or the south to avoid a solar panel producing a

shadow on a lower solar panel. Instead of an exactly vertical tower one

can choose a tower with an axis directed to the

polar star, meaning that it is parallel to the rotation axis of the

Earth.

In this case the angle between the axis and the Sun is always larger

than 66 degrees. During a day it is only necessary to turn the panels

around this axis to follow the Sun. Installations may be ground-mounted

(and sometimes integrated with farming and grazing) or built into the roof or walls of a building (

building-integrated photovoltaics).

Another recent development involves the makeup of solar cells.

Perovskite is a very inexpensive material which is being used to replace the expensive

crystalline silicon

which is still part of a standard PV cell build to this day. Michael

Graetzel, Director of the Laboratory of Photonics and Interfaces at EPFL

says, "Today, efficiency has peaked at 18 percent, but it's expected to

get even higher in the future." This is a significant claim, as 20% efficiency is typical among solar panels which use more expensive materials.

Efficiency

Best Research-Cell Efficiencies

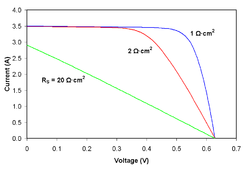

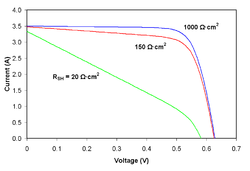

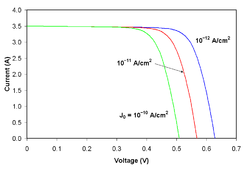

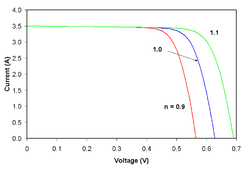

Electrical efficiency (also called conversion efficiency) is a

contributing factor in the selection of a photovoltaic system. However,

the most efficient solar panels are typically the most expensive, and

may not be commercially available. Therefore, selection is also driven

by cost efficiency and other factors.

The electrical efficiency of a PV cell is a

physical property which represents how much electrical power a cell can produce for a given

insolation.

The basic expression for maximum efficiency of a photovoltaic cell is

given by the ratio of output power to the incident solar power

(radiation flux times area)

The efficiency is measured under ideal laboratory conditions and

represents the maximum achievable efficiency of the PV material. Actual

efficiency is influenced by the output Voltage, current, junction

temperature, light intensity and spectrum.

The most efficient type of solar cell to date is a multi-junction concentrator solar cell with an efficiency of 46.0% produced by

Fraunhofer ISE in December 2014. The highest efficiencies achieved without concentration include a material by

Sharp Corporation at 35.8% using a proprietary triple-junction manufacturing technology in 2009, and Boeing Spectrolab (40.7% also using a triple-layer design). The US company

SunPower produces cells that have an efficiency of 21.5%, well above the market average of 12–18%.

There is an ongoing effort to increase the conversion efficiency

of PV cells and modules, primarily for competitive advantage. In order

to increase the efficiency of solar cells, it is important to choose a

semiconductor material with an appropriate

band gap

that matches the solar spectrum. This will enhance the electrical and

optical properties. Improving the method of charge collection is also

useful for increasing the efficiency. There are several groups of

materials that are being developed. Ultrahigh-efficiency devices

(η>30%)

are made by using GaAs and GaInP2 semiconductors with multijunction

tandem cells. High-quality, single-crystal silicon materials are used to

achieve high-efficiency, low cost cells (η>20%).

Recent developments in Organic photovoltaic cells (OPVs) have

made significant advancements in power conversion efficiency from 3% to

over 15% since their introduction in the 1980s.

To date, the highest reported power conversion efficiency ranges from

6.7% to 8.94% for small molecule, 8.4%–10.6% for polymer OPVs, and 7% to

21% for perovskite OPVs.

OPVs are expected to play a major role in the PV market. Recent

improvements have increased the efficiency and lowered cost, while

remaining environmentally-benign and renewable.

Several companies have begun embedding

power optimizers into PV modules called

smart modules. These modules perform

maximum power point tracking

(MPPT) for each module individually, measure performance data for

monitoring, and provide additional safety features. Such modules can

also compensate for shading effects, wherein a shadow falling across a

section of a module causes the electrical output of one or more strings

of cells in the module to decrease.

One of the major causes for the decreased performance of cells is

overheating. The efficiency of a solar cell declines by about 0.5% for

every 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature. This means that a 100

degree increase in surface temperature could decrease the efficiency of a

solar cell by about half. Self-cooling solar cells are one solution to

this problem. Rather than using energy to cool the surface, pyramid and

cone shapes can be formed from

silica, and attached to the surface of a solar panel. Doing so allows visible light to reach the

solar cells, but reflects

infrared rays (which carry heat).

Growth

Solar photovoltaics is growing rapidly and worldwide installed capacity reached about 300

gigawatts (GW) by the end of 2016. Since 2000, installed capacity has seen a growth factor of about 57.

The total power output of the world’s PV capacity in a calendar year in

2014 is now beyond 200 TWh of electricity. This represents 1% of

worldwide electricity demand. More than 100

countries use solar PV.

China, followed by

Japan and the

United States is now the fastest growing market, while

Germany remains the world's largest producer, contributing more than 7% to its national electricity demands.

Photovoltaics is now, after hydro and wind power, the third most

important renewable energy source in terms of globally installed

capacity.

Several market research and financial companies foresee record-breaking global installation of more than 50 GW in 2015.

China is predicted to take the lead from Germany and to become the

world's largest producer of PV power by installing another targeted

17.8 GW in 2015. India is expected to install 1.8 GW, doubling its annual installations.

By 2018, worldwide photovoltaic capacity is projected to doubled or

even triple to 430 GW. Solar Power Europe (formerly known as EPIA) also

estimates that photovoltaics will meet 10% to 15% of Europe's energy

demand in 2030.

In 2017 a study in

Science estimated that by 2030 global PV installed capacities will be between 3,000 and 10,000 GW. The EPIA/

Greenpeace

Solar Generation Paradigm Shift Scenario (formerly called Advanced

Scenario) from 2010 shows that by the year 2030, 1,845 GW of PV systems

could be generating approximately 2,646 TWh/year of electricity around

the world. Combined with

energy use efficiency

improvements, this would represent the electricity needs of more than

9% of the world's population. By 2050, over 20% of all electricity could

be provided by photovoltaics.

Michael Liebreich, from

Bloomberg New Energy Finance,

anticipates a tipping point for solar energy. The costs of power from

wind and solar are already below those of conventional electricity

generation in some parts of the world, as they have fallen sharply and

will continue to do so. He also asserts, that the electrical grid has

been greatly expanded worldwide, and is ready to receive and distribute

electricity from renewable sources. In addition, worldwide electricity

prices came under strong pressure from renewable energy sources, that

are, in part, enthusiastically embraced by consumers.

Deutsche Bank sees a "second gold rush" for the photovoltaic industry to come.

Grid parity has already been reached in at least 19 markets by January 2014. Photovoltaics will prevail beyond

feed-in tariffs, becoming more competitive as deployment increases and prices continue to fall.

In June 2014

Barclays

downgraded bonds of U.S. utility companies. Barclays expects more

competition by a growing self-consumption due to a combination of

decentralized PV-systems and residential

electricity storage.

This could fundamentally change the utility's business model and

transform the system over the next ten years, as prices for these

systems are predicted to fall.

Top 10 PV countries in 2015 (MW)

Installed and Total Solar Power Capacity in 2015 (MW)

| 1 |

China China |

43,530 |

15,150

|

| 2 |

Germany Germany |

39,700 |

1,450

|

| 3 |

Japan Japan |

34,410 |

11,000

|

| 4 |

United States United States |

25,620 |

7,300

|

| 5 |

Italy Italy |

18,920 |

300

|

| 6 |

United Kingdom United Kingdom |

8,780 |

3,510

|

| 7 |

France France |

6,580 |

879

|

| 8 |

Spain Spain |

5,400 |

56

|

| 9 |

Australia Australia |

5,070 |

935

|

| 10 |

India India |

5,050 |

2,000

|

|

Data: IEA-PVPS Snapshot of Global PV 1992–2015 report, March 2015

|

Environmental impacts of photovoltaic technologies

Types of impacts

While solar photovoltaic (PV) cells are promising for clean

energy production, their deployment is hindered by production costs,

material availability, and toxicity.

Data required to investigate their impact are sometimes affected by a

rather large amount of uncertainty. The values of human labor and water

consumption, for example, are not precisely assessed due to the lack of

systematic and accurate analyses in the scientific literature.

Life cycle assessment

(LCA) is one method of determining environmental impacts from PV. Many

studies have been done on the various types of PV including

first generation, second generation, and

third generation.

Usually these PV LCA studies select a cradle to gate system boundary

because often at the time the studies are conducted, it is a new

technology not commercially available yet and their required balance of

system components and disposal methods are unknown.

A traditional LCA can look at many different impact categories ranging from

global warming potential, eco-toxicity, human toxicity, water depletion, and many others.

Most LCAs of PV have focused on two categories: carbon dioxide

equivalents per kWh and energy pay-back time (EPBT). The EPBT is

defined as " the time needed to compensate for the total renewable- and

non-renewable- primary energy required during the life cycle of a PV

system". A 2015 review of EPBT from first and second generation PV

suggested that there was greater variation in embedded energy than in

efficiency of the cells implying that it was mainly the embedded energy

that needs to reduce to have a greater reduction in EPBT. One difficulty

in determining impacts due to PV is to determine if the wastes are

released to the air, water, or soil during the manufacturing phase. Research is underway to try to understand emissions and releases during the lifetime of PV systems.

Impacts from first-generation PV

Crystalline silicon modules are the most extensively studied PV type in terms of LCA since they are the most commonly used.

Mono-crystalline silicon photovoltaic systems (mono-si) have an average efficiency of 14.0%.

The cells tend to follow a structure of front electrode,

anti-reflection film, n-layer, p-layer, and back electrode, with the sun

hitting the front electrode. EPBT ranges from 1.7 to 2.7 years. The cradle to gate of CO

2-eq/kWh ranges from 37.3 to 72.2 grams.

Techniques to produce

multi-crystalline silicon

(multi-si) photovoltaic cells are simpler and cheaper than mono-si,

however tend to make less efficient cells, an average of 13.2%. EPBT ranges from 1.5 to 2.6 years. The cradle to gate of CO

2-eq/kWh ranges from 28.5 to 69 grams.

Some studies have looked beyond EPBT and GWP to other environmental

impacts. In one such study, conventional energy mix in Greece was

compared to multi-si PV and found a 95% overall reduction in impacts

including carcinogens, eco-toxicity, acidification, eutrophication, and

eleven others.

Impacts from second generation

Cadmium telluride (CdTe) is one of the fastest-growing

thin film based solar cells

which are collectively known as second generation devices. This new

thin film device also shares similar performance restrictions (

Shockley-Queisser efficiency limit)

as conventional Si devices but promises to lower the cost of each

device by both reducing material and energy consumption during

manufacturing. Today the global market share of CdTe is 5.4%, up from

4.7% in 2008. This technology’s highest power conversion efficiency is 21%.

The cell structure includes glass substrate (around 2 mm), transparent

conductor layer, CdS buffer layer (50–150 nm), CdTe absorber and a metal

contact layer.

CdTe PV systems require less energy input in their production

than other commercial PV systems per unit electricity production. The

average CO2-eq/kWh is around 18 grams (cradle to gate). CdTe

has the fastest EPBT of all commercial PV technologies, which varies

between 0.3 and 1.2 years.

Copper Indium Gallium Diselenide (CIGS) is a thin film solar cell based on the copper indium diselenide (CIS) family of chalcopyrite

semiconductors.

CIS and CIGS are often used interchangeably within the CIS/CIGS

community. The cell structure includes soda lime glass as the substrate,

Mo layer as the back contact, CIS/CIGS as the absorber layer, cadmium

sulfide (CdS) or Zn (S,OH)x as the buffer layer, and ZnO:Al as the

front contact.

CIGS is approximately 1/100th the thickness of conventional silicon

solar cell technologies. Materials necessary for assembly are readily

available, and are less costly per watt of solar cell. CIGS based solar

devices resist performance degradation over time and are highly stable

in the field.

Reported global warming potential impacts of CIGS range from 20.5 – 58.8 grams CO

2-eq/kWh of electricity generated for different

solar irradiation (1,700 to 2,200 kWh/m

2/y) and power conversion efficiency (7.8 – 9.12%). EPBT ranges from 0.2 to 1.4 years, while harmonized value of EPBT was found 1.393 years. Toxicity is an issue within the buffer layer of CIGS modules because it contains cadmium and gallium. CIS modules do not contain any heavy metals.

Impacts from third generation

Third-generation PVs are designed to combine the advantages of

both the first and second generation devices and they do not have

Shockley-Queisser limit, a theoretical limit for first and second generation PV cells. The thickness of a third generation device is less than 1 µm.

One emerging alternative and promising technology is based on an

organic-inorganic hybrid solar cell made of methylammonium lead halide

perovskites.

Perovskite PV cells have progressed rapidly over the past few years and have become one of the most attractive areas for PV research.

The cell structure includes a metal back contact (which can be made of

Al, Au or Ag), a hole transfer layer (spiro-MeOTAD, P3HT, PTAA, CuSCN,

CuI, or NiO), and absorber layer (CH

3NH

3PbIxBr

3-x, CH

3NH

3PbIxCl

3-x or CH

3NH

3PbI

3), an electron transport layer (TiO, ZnO, Al

2O

3 or SnO

2) and a top contact layer (fluorine doped tin oxide or tin doped indium oxide).

There are a limited number of published studies to address the environmental impacts of perovskite solar cells.

The major environmental concern is the lead used in the absorber layer.

Due to the instability of perovskite cells lead may eventually be

exposed to fresh water during the use phase. These LCA studies looked

at human and ecotoxicity of perovskite solar cells and found they were

surprisingly low and may not be an environmental issue. Global warming potential of perovskite PVs were found to be in the range of 24–1500 grams CO2-eq/kWh

electricity production. Similarly, reported EPBT of the published paper

range from 0.2 to 15 years. The large range of reported values

highlight the uncertainties associated with these studies. Celik et al.

(2016) critically discussed the assumptions made in perovskite PV LCA

studies.

Two new promising thin film technologies are

copper zinc tin sulfide (Cu

2ZnSnS

4 or CZTS),

zinc phosphide (Zn

3P

2) and single-walled carbon nano-tubes (SWCNT).

These thin films are currently only produced in the lab but may be

commercialized in the future. The manufacturing of CZTS and (Zn

3P

2)

processes are expected to be similar to those of current thin film

technologies of CIGS and CdTe, respectively. While the absorber layer of

SWCNT PV is expected to be synthesized with CoMoCAT method. by Contrary to established thin films such as CIGS and CdTe, CZTS, Zn

3P

2,

and SWCNT PVs are made from earth abundant, nontoxic materials and have

the potential to produce more electricity annually than the current

worldwide consumption. While CZTS and Zn

3P

2

offer good promise for these reasons, the specific environmental

implications of their commercial production are not yet known. Global

warming potential of CZTS and Zn

3P

2 were found 38 and 30 grams CO

2-eq/kWh while their corresponding EPBT were found 1.85 and 0.78 years, respectively. Overall, CdTe and Zn

3P

2 have similar environmental impacts but can slightly outperform CIGS and CZTS.

Celik et al. performed the first LCA study on environmental impacts of

SWCNT PVs, including a laboratory-made 1% efficient device and an

aspirational 28% efficient four-cell tandem device and interpreted the

results by using mono-Si as a reference point.

the results show that compared to monocrystalline Si (mono-Si), the

environmental impacts from 1% SWCNT was ∼18 times higher due mainly to

the short lifetime of three years. However, even with the same short

lifetime, the 28% cell had lower environmental impacts than mono-Si.

Organic and

polymer photovoltaic

(OPV) are a relatively new area of research. The tradition OPV cell

structure layers consist of a semi-transparent electrode, electron

blocking layer, tunnel junction, holes blocking layer, electrode, with

the sun hitting the transparent electrode. OPV replaces silver with

carbon as an electrode material lowering manufacturing cost and making

them more environmentally friendly. OPV are flexible, low weight, and work well with roll-to roll manufacturing for mass production.

OPV uses "only abundant elements coupled to an extremely low embodied

energy through very low processing temperatures using only ambient

processing conditions on simple printing equipment enabling energy

pay-back times". Current efficiencies range from 1–6.5%, however theoretical analyses show promise beyond 10% efficiency.

Many different configurations of OPV exist using different

materials for each layer. OPV technology rivals existing PV technologies

in terms of EPBT even if they currently present a shorter operational

lifetime. A 2013 study analyzed 12 different configurations all with 2%

efficiency, the EPBT ranged from 0.29–0.52 years for 1 m² of PV. The average CO2-eq/kWh for OPV is 54.922 grams.

Economics

Source: Apricus

Source: Apricus

|

There have been major changes in the underlying costs, industry

structure and market prices of solar photovoltaics technology, over the

years, and gaining a coherent picture of the shifts occurring across the

industry value chain globally is a challenge. This is due to: "the

rapidity of cost and price changes, the complexity of the PV supply

chain, which involves a large number of manufacturing processes, the

balance of system (BOS) and installation costs associated with complete

PV systems, the choice of different distribution channels, and

differences between regional markets within which PV is being deployed".

Further complexities result from the many different policy support

initiatives that have been put in place to facilitate photovoltaics

commercialisation in various countries.

The PV industry has seen dramatic drops in module prices since

2008. In late 2011, factory-gate prices for crystalline-silicon

photovoltaic modules dropped below the $1.00/W mark. The $1.00/W

installed cost, is often regarded in the PV industry as marking the

achievement of

grid parity

for PV. Technological advancements, manufacturing process improvements,

and industry re-structuring, mean that further price reductions are

likely in coming years.

As of 2017 power-purchase agreement prices for solar farms below

$0.05/kWh are common in the United States and the lowest bids in several

international countries were about $0.03/kWh.

Financial incentives for photovoltaics, such as

feed-in tariffs,

have often been offered to electricity consumers to install and operate

solar-electric generating systems. Government has sometimes also

offered incentives in order to encourage the PV industry to achieve the

economies of scale

needed to compete where the cost of PV-generated electricity is above

the cost from the existing grid. Such policies are implemented to

promote national or territorial

energy independence,

high tech job creation and reduction of

carbon dioxide emissions

which cause climate change. Due to economies of scale solar panels get

less costly as people use and buy more—as manufacturers increase

production to meet demand, the cost and price is expected to drop in the

years to come.

Solar cell efficiencies vary from 6% for amorphous silicon-based solar cells to 44.0% with multiple-junction

concentrated photovoltaics. Solar cell energy conversion efficiencies for commercially available photovoltaics are around 14–22%.

Concentrated photovoltaics (CPV) may reduce cost by concentrating up to

1,000 suns (through magnifying lens) onto a smaller sized photovoltaic

cell. However, such concentrated solar power requires sophisticated heat

sink designs, otherwise the photovoltaic cell overheats, which reduces

its efficiency and life. To further exacerbate the concentrated cooling

design, the heat sink must be passive, otherwise the power required for

active cooling would reduce the overall efficiency and economy.

Crystalline silicon solar cell prices have fallen from $76.67/Watt in 1977 to an estimated $0.74/Watt in 2013. This is seen as evidence supporting

Swanson's law, an observation similar to the famous

Moore's Law that states that solar cell prices fall 20% for every doubling of industry capacity.

As of 2011, the price of PV modules has fallen by 60% since the

summer of 2008, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates,

putting solar power for the first time on a competitive footing with the

retail price of electricity in a number of sunny countries; an

alternative and consistent price decline figure of 75% from 2007 to 2012

has also been published,

though it is unclear whether these figures are specific to the United

States or generally global. The levelised cost of electricity (

LCOE) from PV is competitive with conventional electricity sources in an expanding list of geographic regions, particularly when the time of generation is included, as electricity is worth more during the day than at night.

There has been fierce competition in the supply chain, and further

improvements in the levelised cost of energy for solar lie ahead, posing

a growing threat to the dominance of fossil fuel generation sources in

the next few years. As time progresses, renewable energy technologies generally get cheaper, while fossil fuels generally get more expensive:

The less solar power costs, the

more favorably it compares to conventional power, and the more

attractive it becomes to utilities and energy users around the globe.

Utility-scale solar power can now be delivered in California at prices

well below $100/MWh ($0.10/kWh) less than most other peak generators,

even those running on low-cost natural gas. Lower solar module costs

also stimulate demand from consumer markets where the cost of solar

compares very favorably to retail electric rates.

As of 2011, the cost of PV has fallen well below that of nuclear

power and is set to fall further. The average retail price of solar

cells as monitored by the Solarbuzz group fell from $3.50/watt to

$2.43/watt over the course of 2011.

For large-scale installations, prices below $1.00/watt

were achieved. A module price of 0.60 Euro/watt ($0.78/watt) was

published for a large scale 5-year deal in April 2012.

By the end of 2012, the "best in class" module price had dropped to $0.50/watt, and was expected to drop to $0.36/watt by 2017.

In many locations, PV has reached grid parity, which is usually

defined as PV production costs at or below retail electricity prices

(though often still above the power station prices for coal or gas-fired

generation without their distribution and other costs). However, in

many countries there is still a need for more access to capital to

develop PV projects. To solve this problem

securitization has been proposed and used to accelerate development of solar photovoltaic projects. For example,

SolarCity offered, the first U.S.

asset-backed security in the solar industry in 2013.

Photovoltaic power is also generated during a time of day that is

close to peak demand (precedes it) in electricity systems with high use

of air conditioning. More generally, it is now evident that, given a

carbon price of $50/ton, which would raise the price of coal-fired power

by 5c/kWh, solar PV will be cost-competitive in most locations. The

declining price of PV has been reflected in rapidly growing

installations, totaling about 23 GW in 2011. Although some consolidation

is likely in 2012, due to support cuts in the large markets of Germany

and Italy, strong growth seems likely to continue for the rest of the

decade. Already, by one estimate, total investment in renewables for

2011 exceeded investment in carbon-based electricity generation.

In the case of self consumption payback time is calculated based

on how much electricity is not brought from the grid. Additionally,

using PV solar power to charge DC batteries, as used in Plug-in Hybrid

Electric Vehicles and Electric Vehicles, leads to greater efficiencies.

Traditionally, DC generated electricity from solar PV must be converted

to AC for buildings, at an average 10% loss during the conversion. An

additional efficiency loss occurs in the transition back to DC for

battery driven devices and vehicles, and using various interest rates

and energy price changes were calculated to find present values that

range from $2,057 to $8,213 (analysis from 2009).

For example, in Germany with electricity prices of 0.25 euro/kWh and

Insolation of 900 kWh/kW one kW

p will save 225 euro per year and with installation cost of 1700 euro/kW

p means that the system will pay back in less than 7 years.

Manufacturing

Overall the

manufacturing process of creating solar photovoltaics is simple in that it does

not require the culmination of many complex or moving parts. Because of the

solid state nature of PV systems they often have relatively long lifetimes,

anywhere from 10 to 30 years. To increase electrical output of a PV

system, the manufacturer must simply add more photovoltaic components and

because of this economies of scale are important for manufacturers as costs

decrease with increasing output.

While there are many types of PV systems known to be effective,

crystalline silicon PV accounted for around 90% of the worldwide

production of PV in 2013. Manufacturing silicon PV systems has several

steps. First, polysilicon is processed from mined quartz until it is

very pure (semi-conductor grade). This is melted down when small amounts

of

boron,

a group III element, are added to make a p-type semiconductor rich in

electron holes. Typically using a seed crystal, an ingot of this

solution is grown from the liquid polycrystalline. The ingot may also be

cast in a mold. Wafers of this semiconductor material are cut from the

bulk material with wire saws, and then go through surface etching before

being cleaned. Next, the wafers are placed into a phosphorus vapor

deposition furnace which lays a very thin layer of phosphorus, a group V

element, which creates an n-type semiconducting surface. To reduce

energy losses, an anti-reflective coating is added to the surface, along

with electrical contacts. After finishing the cell, cells are connected

via electrical circuit according to the specific application and

prepared for shipping and installation.

Crystalline silicon photovoltaics are only one type of PV, and

while they represent the majority of solar cells produced currently

there are many new and promising technologies that have the potential to

be scaled up to meet future energy needs. As of 2018, crystalline

silicon cell technology serves as the basis for several PV module types,

including monocrystalline, multicrystalline, mono PERC, and bifacial.

Another newer technology, thin-film PV, are manufactured by

depositing semiconducting layers on substrate in vacuum. The substrate

is often glass or stainless-steel, and these semiconducting layers are

made of many types of materials including cadmium telluride (CdTe),

copper indium diselenide (CIS), copper indium gallium diselenide (CIGS),

and amorphous silicon (a-Si). After being deposited onto the substrate

the semiconducting layers are separated and connected by electrical

circuit by laser-scribing. Thin-film photovoltaics now make up around

20% of the overall production of PV because of the reduced materials

requirements and cost to manufacture modules consisting of thin-films as

compared to silicon-based wafers.

Other emerging PV technologies include organic, dye-sensitized,

quantum-dot, and Perovskite photovoltaics. OPVs fall into the thin-film

category of manufacturing, and typically operate around the 12%

efficiency range which is lower than the 12–21% typically seen by

silicon based PVs. Because organic photovoltaics require very high

purity and are relatively reactive they must be encapsulated which

vastly increases cost of manufacturing and meaning that they are not

feasible for large scale up. Dye-sensitized PVs are similar in

efficiency to OPVs but are significantly easier to manufacture. However

these dye-sensitized photovoltaics present storage problems because the

liquid electrolyte is toxic and can potentially permeate the plastics

used in the cell. Quantum dot solar cells are quantum dot sensitized

DSSCs and are solution processed meaning they are potentially scalable,

but currently they peak at 12% efficiency. Perovskite solar cells are a

very efficient solar energy converter and have excellent optoelectric

properties for photovoltaic purposes, but they are expensive and

difficult to manufacture.

Applications

Photovoltaic systems

A photovoltaic system, or solar PV system is a power system designed

to supply usable solar power by means of photovoltaics. It consists of

an arrangement of several components, including solar panels to absorb

and directly convert sunlight into electricity, a solar inverter to

change the electric current from DC to AC, as well as mounting, cabling

and other electrical accessories. PV systems range from small,

roof-top mounted or

building-integrated systems with capacities from a few to several tens of

kilowatts, to large utility-scale

power stations of hundreds of

megawatts. Nowadays, most PV systems are

grid-connected, while

stand-alone systems only account for a small portion of the market.

-

- Rooftop and building integrated systems

Rooftop PV on half-timbered house

- Photovoltaic arrays are often associated with buildings: either

integrated into them, mounted on them or mounted nearby on the ground. Rooftop PV systems

are most often retrofitted into existing buildings, usually mounted on

top of the existing roof structure or on the existing walls.

Alternatively, an array can be located separately from the building but

connected by cable to supply power for the building. Building-integrated photovoltaics

(BIPV) are increasingly incorporated into the roof or walls of new

domestic and industrial buildings as a principal or ancillary source of

electrical power.

Roof tiles with integrated PV cells are sometimes used as well.

Provided there is an open gap in which air can circulate, rooftop

mounted solar panels can provide a passive cooling effect on buildings

during the day and also keep accumulated heat in at night.

Typically, residential rooftop systems have small capacities of around

5–10 kW, while commercial rooftop systems often amount to several

hundreds of kilowatts. Although rooftop systems are much smaller than

ground-mounted utility-scale power plants, they account for most of the

worldwide installed capacity.

-

- Concentrator photovoltaics

- Concentrator photovoltaics

(CPV) is a photovoltaic technology that contrary to conventional

flat-plate PV systems uses lenses and curved mirrors to focus sunlight

onto small, but highly efficient, multi-junction (MJ) solar cells. In addition, CPV systems often use solar trackers

and sometimes a cooling system to further increase their efficiency.

Ongoing research and development is rapidly improving their

competitiveness in the utility-scale segment and in areas of high solar insolation.

-

- Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector

- Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector (PVT) are systems that convert solar radiation into thermal and electrical energy. These systems combine a solar PV cell, which converts sunlight into electricity, with a solar thermal collector,

which captures the remaining energy and removes waste heat from the PV

module. The capture of both electricity and heat allow these devices to

have higher exergy and thus be more overall energy efficient than solar PV or solar thermal alone.

- Many utility-scale solar farms have been constructed all over the world. As of 2015, the 579-megawatt (MWAC) Solar Star is the world's largest photovoltaic power station, followed by the Desert Sunlight Solar Farm and the Topaz Solar Farm, both with a capacity of 550 MWAC, constructed by US-company First Solar, using CdTe modules, a thin-film PV technology.

All three power stations are located in the Californian desert. Many

solar farms around the world are integrated with agriculture and some

use innovative solar tracking systems that follow the sun's daily path

across the sky to generate more electricity than conventional

fixed-mounted systems. There are no fuel costs or emissions during

operation of the power stations.

- Developing countries

where many villages are often more than five kilometers away from grid

power are increasingly using photovoltaics. In remote locations in India

a rural lighting program has been providing solar powered LED lighting to replace kerosene lamps. The solar powered lamps were sold at about the cost of a few months' supply of kerosene. Cuba is working to provide solar power for areas that are off grid. More complex applications of off-grid solar energy use include 3D printers. RepRap 3D printers have been solar powered with photovoltaic technology, which enables distributed manufacturing for sustainable development.

These are areas where the social costs and benefits offer an excellent

case for going solar, though the lack of profitability has relegated

such endeavors to humanitarian efforts. However, in 1995 solar rural electrification

projects had been found to be difficult to sustain due to unfavorable

economics, lack of technical support, and a legacy of ulterior motives

of north-to-south technology transfer.

- Until a decade or so ago, PV was used frequently to power

calculators and novelty devices. Improvements in integrated circuits and

low power liquid crystal displays

make it possible to power such devices for several years between

battery changes, making PV use less common. In contrast, solar powered

remote fixed devices have seen increasing use recently in locations

where significant connection cost makes grid power prohibitively

expensive. Such applications include solar lamps, water pumps, parking meters, emergency telephones, trash compactors, temporary traffic signs, charging stations, and remote guard posts and signals.

- In May 2008, the Far Niente Winery in Oakville, CA pioneered the

world's first "floatovoltaic" system by installing 994 photovoltaic

solar panels onto 130 pontoons and floating them on the winery's

irrigation pond. The floating system generates about 477 kW of peak

output and when combined with an array of cells located adjacent to the

pond is able to fully offset the winery's electricity consumption.

The primary benefit of a floatovoltaic system is that it avoids the

need to sacrifice valuable land area that could be used for another

purpose. In the case of the Far Niente Winery, the floating system saved

three-quarters of an acre that would have been required for a

land-based system. That land area can instead be used for agriculture.

Another benefit of a floatovoltaic system is that the panels are kept

at a lower temperature than they would be on land, leading to a higher

efficiency of solar energy conversion. The floating panels also reduce

the amount of water lost through evaporation and inhibit the growth of

algae.

- PV has traditionally been used for electric power in space. PV

is rarely used to provide motive power in transport applications, but is

being used increasingly to provide auxiliary power in boats and cars.

Some automobiles are fitted with solar-powered air conditioning to limit

interior temperatures on hot days. A self-contained solar vehicle would have limited power and utility, but a solar-charged electric vehicle allows use of solar power for transportation. Solar-powered cars, boats and airplanes have been demonstrated, with the most practical and likely of these being solar cars. The Swiss solar aircraft, Solar Impulse 2, achieved the longest non-stop solo flight in history and completed the first solar-powered aerial circumnavigation of the globe in 2016.

-

- Telecommunication and signaling

- Solar PV power is ideally suited for telecommunication

applications such as local telephone exchange, radio and TV

broadcasting, microwave and other forms of electronic communication

links. This is because, in most telecommunication application, storage

batteries are already in use and the electrical system is basically DC.

In hilly and mountainous terrain, radio and TV signals may not reach as

they get blocked or reflected back due to undulating terrain. At these

locations, low power transmitters (LPT) are installed to receive and retransmit the signal for local population.

Part of Juno's solar array

- Solar panels on spacecraft

are usually the sole source of power to run the sensors, active heating

and cooling, and communications. A battery stores this energy for use

when the solar panels are in shadow. In some, the power is also used

for spacecraft propulsion—electric propulsion. Spacecraft were one of the earliest applications of photovoltaics, starting with the silicon solar cells used on the Vanguard 1 satellite, launched by the US in 1958. Since then, solar power has been used on missions ranging from the MESSENGER probe to Mercury, to as far out in the solar system as the Juno probe to Jupiter. The largest solar power system flown in space is the electrical system of the International Space Station.

To increase the power generated per kilogram, typical spacecraft solar

panels use high-cost, high-efficiency, and close-packed rectangular multi-junction solar cells made of gallium arsenide (GaAs) and other semiconductor materials.

- Photovoltaics may also be incorporated as energy conversion

devices for objects at elevated temperatures and with preferable

radiative emissivities such as heterogeneous combustors.

Advantages

The 122

PW

of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface is plentiful—almost 10,000

times more than the 13 TW equivalent of average power consumed in 2005

by humans.

This abundance leads to the suggestion that it will not be long before

solar energy will become the world's primary energy source. Additionally, solar electric generation has the highest power density (global mean of 170 W/m

2) among renewable energies.

Solar power is pollution-free during use, which enables it to cut

down on pollution when it is substituted for other energy sources. For

example,

MIT estimated that 52,000 people per year die prematurely in the U.S. from coal-fired power plant pollution and all but one of these deaths could be prevented from using PV to replace coal.

Production end-wastes and emissions are manageable using existing

pollution controls. End-of-use recycling technologies are under

development and policies are being produced that encourage recycling from producers.

PV installations can operate for 100 years or even more with little maintenance or intervention after their initial set-up, so after the initial

capital cost of building any solar power plant,

operating costs are extremely low compared to existing power technologies.

Grid-connected solar electricity can be used locally thus

reducing transmission/distribution losses (transmission losses in the US

were approximately 7.2% in 1995).

Compared to fossil and nuclear energy sources, very little

research money has been invested in the development of solar cells, so

there is considerable room for improvement. Nevertheless, experimental

high efficiency solar cells already have efficiencies of over 40% in case of concentrating photovoltaic cells and efficiencies are rapidly rising while mass-production costs are rapidly falling.

In some states of the United States, much of the investment in a

home-mounted system may be lost if the home-owner moves and the buyer

puts less value on the system than the seller. The city of

Berkeley

developed an innovative financing method to remove this limitation, by

adding a tax assessment that is transferred with the home to pay for the

solar panels. Now known as

PACE, Property Assessed Clean Energy, 30 U.S. states have duplicated this solution.

There is evidence, at least in California, that the presence of a

home-mounted solar system can actually increase the value of a home.

According to a paper published in April 2011 by the Ernest Orlando

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory titled An Analysis of the Effects

of Residential Photovoltaic Energy Systems on Home Sales Prices in

California:

The research finds strong evidence

that homes with PV systems in California have sold for a premium over

comparable homes without PV systems. More specifically, estimates for

average PV premiums range from approximately $3.9 to $6.4 per installed

watt (DC) among a large number of different model specifications, with

most models coalescing near $5.5/watt. That value corresponds to a

premium of approximately $17,000 for a relatively new 3,100 watt PV

system (the average size of PV systems in the study).

Limitations

-

- Pollution and Energy in Production

PV has been a well-known method of generating clean, emission free

electricity. PV systems are often made of PV modules and inverter

(changing DC to AC). PV modules are mainly made of PV cells, which has

no fundamental difference to the material for making computer chips. The

process of producing PV cells (computer chips) is energy intensive and

involves highly poisonous and environmental toxic chemicals. There are

few PV manufacturing plants around the world producing PV modules with

energy produced from PV. This measure greatly reduces the carbon

footprint during the manufacturing process. Managing the chemicals used

in the manufacturing process is subject to the factories' local laws and

regulations.

-

- Impact on Electricity Network

With the increasing levels of rooftop photovoltaic systems, the

energy flow becomes 2-way. When there is more local generation than

consumption, electricity is exported to the grid. However, electricity

network traditionally is not designed to deal with the 2- way energy

transfer. Therefore, some technical issues may occur. For example, in

Queensland Australia, there have been more than 30% of households with

rooftop PV by the end of 2017. The famous Californian 2020 duck curve

appears very often for a lot of communities from 2015 onwards. An

over-voltage issue may come out as the electricity flows from these PV

households back to the network.

There are solutions to manage the over voltage issue, such as

regulating PV inverter power factor, new voltage and energy control

equipment at electricity distributor level, re-conductor the electricity

wires, demand side management, etc. There are often limitations and

costs related to these solutions.

-

- Implication onto Electricity Bill Management and Energy Investment

There is no silver bullet in electricity or energy demand and bill

management, because customers (sites) have different specific

situations, e.g. different comfort/convenience needs, different

electricity tariffs, or different usage patterns. Electricity tariff may

have a few elements, such as daily access and metering charge, energy

charge (based on kWh, MWh) or peak demand charge (e.g. a price for the

highest 30min energy consumption in a month). PV is a promising option

for reducing energy charge when electricity price is reasonably high and

continuously increasing, such as in Australia and Germany. However, for

sites with peak demand charge in place, PV may be less attractive if

peak demands mostly occur in the late afternoon to early evening, for

example residential communities. Overall, energy investment is largely

an economical decision and it is better to make investment decisions

based on systematical evaluation of options in operational improvement,

energy efficiency, onsite generation and energy storage.

![{\displaystyle I_{D}=I_{0}\left\{\exp \left[{\frac {V_{j}}{nV_{T}}}\right]-1\right\}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0b50e360bdf5d4b6a17729bcfddff18aba2151d9)