From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Buddhism,

once thought of as a mysterious religion from the East, has now become

very popular in the West, and is one of the largest religions in the

United States.

As Buddhism does not require any formal "conversion", American

Buddhists can easily incorporate dharma practice into their normal

routines and traditions. The result is that American Buddhists come from

every ethnicity, nationality and religious tradition. In 2012,

U-T San Diego estimated U.S. practitioners at 1.2 million people, of whom 40% are living in

Southern California. In terms of percentage,

Hawaii has the most Buddhists at 8% of the population due to its large

Asian American community.

The term

American Buddhism can be used to describe Buddhist groups within the U.S, which are largely made up of converts. This contrasts with many Buddhist groups in Asia, which are largely made up of people who were born into the faith.

Covering 15 acres (61,000 m²), California's Hsi Lai Temple is one of the largest Buddhist temples in the western hemisphere.

Services at the Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, Los Angeles, around 1925.

US States by Population of Buddhists

Hawaii has the largest Buddhist population, amounting to 8% of the total Buddhist population of the United States.

California

follows Hawaii with 2%. Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut,

Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan,

Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, South Dakota,

Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming have 1%

buddhist population.

Buddhism in American Overseas territories

The following is the percentage of Buddhists in the U.S. territories as of 2010:

Types of Buddhism in the United States

Buddhist American scholar Charles Prebish states there are three broad types of American Buddhism:

- The oldest and largest of these is "immigrant" or "ethnic

Buddhism", those Buddhist traditions that arrived in America along with

immigrants who were already practitioners and that largely remained with

those immigrants and their descendants.

- The next oldest and arguably the most visible group Prebish refers

to as "import Buddhists", because they came to America largely in

response to interested American converts who sought them out, either by

going abroad or by supporting foreign teachers; this is sometimes also

called "elite Buddhism" because its practitioners, especially early

ones, tended to come from social elites.

- A trend in Buddhism is "export" or "evangelical Buddhist" groups

based in another country who actively recruit members in the US from

various backgrounds. Modern Buddhism is not just an American phenomenon.

Nichiren: Soka Gakkai International

Soka Gakkai International (SGI) is perhaps the most successful of Japan's

new religious movements that grew around the world after the end of

World War II.

Soka Gakkai, which means "Value Creation Society," is one of three sects of

Nichiren Buddhism that came to the United States during the 20th century. The SGI expanded rapidly in the US, attracting non-

Asian minority converts, chiefly

African Americans and

Latino, as well as the support of celebrities, such as

Tina Turner,

Herbie Hancock, and

Orlando Bloom. Because of a rift with

Nichiren Shōshū in 1991, the SGI has no

priests of its own. Its main religious practice is chanting the mantra

Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō and sections of the

Lotus Sutra. Unlike trends such as

Zen,

Vipassanā, and

Tibetan Buddhism, Soka Gakkai Buddhists do not practice meditative techniques other than chanting. An SGI

YouTube series called "Buddhist in America" has over a quarter million views in total as of 2015.

Immigrant Buddhism

Chùa Huệ Quang Buddhist Temple, a Vietnamese American temple in Garden Grove

Wat Buddharangsi Buddhist Temple of Miami

Buddhism was introduced into the USA by Asian immigrants in the 19th century, when significant numbers of immigrants from

East Asia began to arrive in the New World. In the United States, immigrants from

China entered around 1820, but began to arrive in large numbers following the 1849

California Gold Rush.

Huishen

Chinese immigration

The first

Buddhist temple in America was built in 1853 in

San Francisco by the Sze Yap Company, a

Chinese American

fraternal society. Another society, the Ning Yeong Company, built a

second in 1854; by 1875, there were eight temples, and by 1900

approximately 400 Chinese temples on the west coast of the United

States, most of them containing some Buddhist elements. Unfortunately a

casualty of

racism, these temples were often the subject of suspicion and ignorance by the rest of the population, and were dismissively called

joss houses.

Japanese and Korean immigration

The

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 curtailed growth of the Chinese American population, but large-scale immigration from

Japan began in the late 1880s and from

Korea around 1903. In both cases, immigration was at first primarily to

Hawaii. Populations from other Asian Buddhist countries followed, and in each case, the new communities established

Buddhist temples

and organizations. For instance, the first Japanese temple in Hawaii

was built in 1896 near Paauhau by the Honpa Hongwanji branch of

Jodo Shinshu.

In 1898, Japanese missionaries and immigrants established a Young Men's

Buddhist Association, and the Rev. Sōryū Kagahi was dispatched from

Japan to be the first Buddhist missionary in Hawaii. The first Japanese Buddhist temple in the continental U.S. was built in

San Francisco in 1899, and the first in

Canada was built at the Ishikawa Hotel in

Vancouver in 1905. The first

Buddhist clergy

to take up residence in the continental U.S. were Shuye Sonoda and

Kakuryo Nishimjima, missionaries from Japan who arrived in 1899.

Contemporary Immigrant Buddhism

Japanese Buddhism

Buddhist Churches of America

The

Buddhist Churches of America and the

Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii are immigrant Buddhist organizations in the United States. The BCA is an affiliate of Japan's Nishi Hongwanji, a sect of

Jōdo Shinshū, which is, in turn, a form of

Pure Land Buddhism.

Tracing its roots to the Young Men's Buddhist Association founded in

San Francisco at the end of the 19th century and the Buddhist Mission of

North America founded in 1899,

it took its current form in 1944. All of the Buddhist Mission's

leadership, along with almost the entire Japanese American population,

had been interned during

World War II. The name

Buddhist Churches of America was adopted at

Topaz War Relocation Center in

Utah;

the word "church" was used similar to a Christian house of worship.

After internment ended, some members returned to the West Coast and

revitalized churches there, while a number of others moved to the

Midwest

and built new churches. During the 1960s and 1970s, the BCA was in a

growth phase and was very successful at fund-raising. It also published

two periodicals, one in

Japanese and one in

English.

However, since 1980, BCA membership declined. The 36 temples in the

state of Hawaii of the Honpa Hongwanji Mission have a similar history.

While a majority of the Buddhist Churches of America's membership are

ethnically Japanese,

some members have non-Asian backgrounds. Thus, it has limited aspects

of export Buddhism. As involvement by its ethnic community declined,

internal discussions advocated attracting the broader public.

Taiwanese Buddhism

Another US Buddhist institution is

Hsi Lai Temple in

Hacienda Heights, California. Hsi Lai is the American headquarters of

Fo Guang Shan, a modern Buddhist group in

Taiwan.

Hsi Lai was built in 1988 at a cost of $10 million and is often

described as the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere.

Although it caters primarily to Chinese Americans, it also has regular

services and outreach programs in English. Hsi Lai was at the center of a

campaign finance controversy by Vice President

Al Gore.

Import Buddhism

While

Asian immigrants were arriving, some American intellectuals examined

Buddhism, based primarily on information from British colonies in India

and East Asia.

In the last century, numbers of Asian Buddhist masters and

teachers have immigrated to the U.S. in order to propagate their beliefs

and practices. Most have belonged to three major Buddhist traditions or

cultures:

Zen,

Tibetan, and

Theravadan.

Early translations

Theosophical Society

An early American to publicly convert to Buddhism was

Henry Steel Olcott. Olcott, a former U.S. army colonel during the

Civil War, had grown interested in reports of supernatural phenomena that were popular in the late 19th century. In 1875, he,

Helena Blavatsky, and

William Quan Judge founded the

Theosophical Society,

dedicated to the study of the occult and influenced by Hindu and

Buddhist scriptures. The leaders claimed to believe that they were in

contact, via visions and messages, with a secret order of

adepts called the "Himalayan Brotherhood" or "the Masters". In 1879, Olcott and Blavatsky travelled to India and in 1880, to

Sri Lanka,

where they were met enthusiastically by local Buddhists, who saw them

as allies against an aggressive Christian missionary movement. On May

25, Olcott and Blavatsky took the

pancasila

vows of a lay Buddhist before a monk and a large crowd. Although most

of the Theosophists appear to have counted themselves as Buddhists, they

held idiosyncratic beliefs that separated them from known Buddhist

traditions; only Olcott was enthusiastic about following mainstream

Buddhism. He returned twice to Sri Lanka, where he promoted Buddhist

education, and visited Japan and

Burma. Olcott authored a

Buddhist Catechism, stating his view of the basic tenets of the religion.

Paul Carus

Several publications increased knowledge of Buddhism in 19th-century America. In 1879,

Edwin Arnold, an English aristocrat, published

The Light of Asia, an epic poem he had written about the life and teachings of

the Buddha,

expounded with much wealth of local color and not a little felicity of

versification. The book became immensely popular in the United States,

going through eighty editions and selling more than 500,000 copies.

Paul Carus, a German American philosopher and

theologian, was at work on a more scholarly prose treatment of the same subject. Carus was the director of

Open Court Publishing Company, an academic publisher specializing in

philosophy,

science, and

religion, and editor of

The Monist, a journal with a similar focus, both based in

La Salle, Illinois. In 1894, Carus published

The Gospel of Buddha,

compiled from a variety of Asian texts which, true to its name,

presented the Buddha's story in a form resembling the Christian

Gospels.

Early converts

In a brief ceremony conducted by Dharmapala,

Charles T. Strauss, a New York businessman of Jewish descent, became one of the first to formally convert to Buddhism on American soil. A few fledgling attempts at establishing a Buddhism for Americans followed. Appearing with little fanfare in 1887:

The Buddhist Ray, a

Santa Cruz, California-based

magazine published and edited by Phillangi Dasa, born Herman Carl (or

Carl Herman) Veetering (or Vettering), a recluse about whom little is

known. The

Ray's tone was "ironic, light, saucy, self-assured ... one-hundred-percent American Buddhist".

It ceased publication in 1894. In 1900 six white San Franciscans,

working with Japanese Jodo Shinshu missionaries, established the Dharma

Sangha of Buddha and published a bimonthly magazine,

The Light of Dharma. In Illinois, Paul Carus wrote more books about Buddhism and set portions of Buddhist scripture to Western classical music.

Dwight Goddard

One American who attempted to establish an American Buddhist movement was

Dwight Goddard

(1861–1939). Goddard was a Christian missionary to China when he first

came in contact with Buddhism. In 1928, he spent a year living at a Zen

monastery in Japan. In 1934, he founded "The Followers of Buddha, an

American Brotherhood", with the goal of applying the traditional

monastic structure of Buddhism more strictly than Senzaki and Sokei-an.

The group was largely unsuccessful: no Americans were recruited to join

as monks and attempts failed to attract a Chinese

Chan

(Zen) master to come to the United States. However, Goddard's efforts

as an author and publisher bore considerable fruit. In 1930, he began

publishing

ZEN: A Buddhist Magazine. In 1932, he collaborated with

D. T. Suzuki, on a translation of the

Lankavatara Sutra. That same year, he published the first edition of

A Buddhist Bible, an anthology of Buddhist scriptures focusing on those used in Chinese and Japanese Zen.

Zen

Japanese Rinzai

Zen

was introduced to the United States by Japanese priests who were sent

to serve local immigrant groups. A small group also came to study the

American culture and way of life.

Early Rinzai-teachers

In 1893,

Soyen Shaku was invited to speak at the

World Parliament of Religions held in

Chicago.

In 1905, Shaku was invited to stay in the United States by a wealthy

American couple. He lived for nine months near San Francisco, where he

established a small

zendo in the Alexander and Ida Russell home and gave regular

zazen lessons, making him the first Zen Buddhist priest to teach in

North America.

Shaku was followed by

Nyogen Senzaki, a young monk from Shaku's home temple in

Japan.

Senzaki briefly worked for the Russells and then as a hotel porter,

manager and eventually, owner. In 1922 Senzaki rented a hall and gave an

English talk on a paper by Shaku; his periodic talks at different

locations became known as the "floating zendo". Senzaki established an

itinerant sitting hall from

San Francisco to

Los Angeles in California, where he taught until his death in 1958.

Sokatsu Shaku, one of Shaku's senior students, arrived in late 1906, founding a Zen meditation center called

Ryomokyo-kai. One of his disciples,

Shigetsu Sasaki, better known under his monastic name Sokei-an, came to New York to teach. In 1931, his small group incorporated as the

Buddhist Society of America, later renamed the First Zen Institute of America. By the late 1930s, one of his most active supporters was

Ruth Fuller Everett, an American socialite and the mother-in-law of

Alan Watts. Shortly before Sokei-an's death in 1945, he and Everett would wed, at which point she took the name

Ruth Fuller Sasaki.

D.T. Suzuki

D.T. Suzuki had a great literary impact. Through English language essays and books, such as

Essays in Zen Buddhism (1927), he became a visible expositor of Zen Buddhism and its unofficial ambassador to Western readers. In 1951,

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki returned to the United States to take a visiting professorship at

Columbia University, where his open lectures attracted many members of the literary, artistic, and cultural elite.

Beat Zen

In the mid-1950s, writers associated with the

Beat Generation took a serious interest in Zen, including

Gary Snyder,

Jack Kerouac,

Allen Ginsberg, and

Kenneth Rexroth, which increased its visibility. Prior to that,

Philip Whalen had interest as early as 1946, and D. T. Suzuki began lecturing on Buddhism at Columbia in 1950. By 1958, anticipating Kerouac's publication of

The Dharma Bums by three months,

Time magazine said, "Zen Buddhism is growing more chic by the minute."

Contemporary Rinzai

The Zen Buddhist Temple in Chicago, part of the Buddhist Society for Compassionate Wisdom

In 1998

Sherry Chayat, born in Brooklyn, became the first American woman to receive transmission in the Rinzai school of Buddhism.

Soyu Matsuoka

In the 1930s Soyu Matsuoka-roshi was sent to America by Sōtōshū, to

establish the Sōtō Zen tradition in the United States. He established

the Chicago Buddhist Temple in 1949. Matsuoka-roshi also served as

superintendent and abbot of the Long Beach Zen Buddhist Temple and Zen

Center. He relocated from Chicago to establish a temple at Long Beach in

1971 after leaving the Zen Buddhist Temple of Chicago to his dharma

heir Kongo Richard Langlois, Roshi. He returned to

Chicago in 1995, where he died in 1998.

Shunryu Suzuki

Sōtō Zen priest Shunryu Suzuki (no relation to

D.T. Suzuki),

who was the son of a Sōtō priest, was sent to San Francisco in the late

1950s on a three-year temporary assignment to care for an established

Japanese congregation at the Sōtō temple, Soko-ji. Suzuki also taught zazen or sitting meditation which soon attracted American students and "

beatniks", who formed a core of students who in 1962 would create the

San Francisco Zen Center and its eventual network of highly influential Zen centers across the country, including the

Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, the first Buddhist monastery in the Western world. He provided innovation and creativity during San Francisco's

countercultural movement of the 1960s but he died in 1971. His low-key teaching style was described in the popular book

Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, a compilation of his talks.

White Plum Sangha

Taizan Maezumi arrived as a young priest to serve at Zenshuji, the North American

Sōtō sect headquarters in Los Angeles, in 1956. Maezumi received dharma transmission (

shiho)

from Baian Hakujun Kuroda, his father and high-ranked Sōtō priest, in

1955. By the mid-1960s he had formed a regular zazen group. In 1967, he

and his supporters founded the

Zen Center of Los Angeles. Further, he received teaching permission (

inka) from Koryu Osaka – a

Rinzai teacher – and from

Yasutani Hakuun of the Sanbo Kyodan. Maezumi, in turn, had several American dharma heirs, such as

Bernie Glassman,

John Daido Loori,

Charlotte Joko Beck, and

Dennis Genpo Merzel. His successors and their network of centers became the

White Plum Sangha. In 2006

Merle Kodo Boyd, born in Texas, became the first African-American woman ever to receive Dharma transmission in Zen Buddhism.

Sanbo Kyodan

Sanbo Kyodan

is a contemporary Japanese Zen lineage which had an impact in the West

disproportionate to its size in Japan. It is rooted in the reformist

teachings of

Harada Daiun Sogaku (1871–1961) and his disciple

Yasutani Hakuun (1885–1971), who argued that the existing Zen institutions of Japan (

Sōtō and

Rinzai sects) had become complacent and were generally unable to convey real

Dharma.

Philip Kapleau

Sanbo Kyodan's first American member was Philip Kapleau, who first

traveled to Japan in 1945 as a court reporter for the war crimes trials.

In 1953, he returned to Japan, where he met with

Nakagawa Soen, a protégé of

Nyogen Senzaki. In 1965, he published a book,

The Three Pillars of Zen, which recorded a set of talks by Yasutani outlining his approach to practice, along with transcripts of

dokusan interviews and some additional texts. In 1965 Kapleau returned to America and, in 1966, established the

Rochester Zen Center in

Rochester, New York.

In 1967, Kapleau had a falling-out with Yasutani over Kapleau's moves

to Americanize his temple, after which it became independent of Sanbo

Kyodan. One of Kapleau's early disciples was

Toni Packer, who left Rochester in 1981 to found a nonsectarian meditation center, not specifically Buddhist or Zen.

Robert Aitken

Robert Aitken was introduced to Zen as a prisoner in Japan during

World War II. After returning to the United States, he studied with

Nyogen Senzaki in

Los Angeles in the early 1950s. In 1959, while still a Zen student, he founded the

Diamond Sangha, a zendo in

Honolulu, Hawaii.

Aitken became a dharma heir of Yamada's, authored more than ten books,

and developed the Diamond Sangha into an international network with

temples in the United States, Argentina, Germany, and Australia. In

1995, he and his organization split with Sanbo Kyodan in response to

reorganization of the latter following Yamada's death. The

Pacific Zen Institute led by

John Tarrant, Aitken's first Dharma successor, continues as an independent Zen line.

Chinese Chán

There are also Zen teachers of Chinese Chán, Korean Seon, and Vietnamese Thien.

Hsuan Hua

In 1962, Hsuan Hua moved to San Francisco's

Chinatown, where, in addition to Zen, he taught Chinese Pure Land,

Tiantai,

Vinaya, and

Vajrayana Buddhism. Initially, his students were mostly ethnic Chinese, but he eventually attracted a range of followers.

Sheng-yen

Sheng-yen first visited the United States in 1978 under the sponsorship of the

Buddhist Association of the United States, an organization of Chinese American Buddhists. In 1980, he founded the Chán Meditation Society in

Queens, New York.

In 1985, he founded the Chung-hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies in

Taiwan, which sponsors Chinese Zen activities in the United States.

Korean Seon

Hye Am (1884–1985) brought lineage Dharma to the United States. Hye Am's Dharma successor, Myo Vong founded the Western Son Academy (1976), and his Korean disciple,

Pohwa

Sunim, founded World Zen Fellowship (1994) which includes various Zen

centers in the United States, such as the Potomac Zen Sangha, the

Patriarchal Zen Society and the Baltimore Zen Center.

Recently, many Korean Buddhist monks have come to the United

States to spread the Dharma. They are establishing temples and zen

(Korean, 'Seon') centers all around the United States. For example,

Hyeonho established the Goryosah Temple in Los Angeles in 1979, and Muil

Woohak founded the Budzen Center in New York.

Vietnamese Thien

Vietnamese Zen (

Thiền) teachers in America include Thich

Thien-An and Thich

Nhat Hanh. Thich

Thien-An came to America in 1966 as a visiting professor at

UCLA and taught traditional Thien meditation.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Tibetan Buddhism

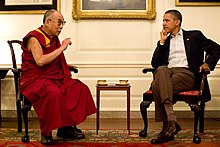

Perhaps the most widely visible Buddhist leader in the world is

Tenzin Gyatso, the current

Dalai Lama, who first visited the United States in 1979. As the exiled political leader of

Tibet, he has become a popular cause célèbre, attracting celebrity religious followers such as

Richard Gere and

Adam Yauch. His early life was depicted in Hollywood films such as

Kundun and

Seven Years in Tibet. An early Western-born Tibetan Buddhist monk was

Robert A. F. Thurman, now an academic supporter of the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama maintains a North American headquarters in

Ithaca, New York.

The Dalai Lama's family has strong ties to America. His brother

Thubten Norbu fled China after being asked to assassinate his brother. He was himself a Lama, the

Takster Rinpoche, and an abbot of the

Kumbum Monastery in Tibet's

Amdo region. He settled in

Bloomington, Indiana,

where he later founded the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center

and Kumbum Chamtse Ling Temple. Since the death of the Takster Rinpoche

it has served as a Kumbum of the West, with the current Arija Rinpochere

serving as its leader.

Dilowa Gegen (Diluu Khudagt) was the first lama to immigrate to

the United States in 1949 as a political refugee and joined Owen

Lattimore's Mongolia Project. He was born in Tudevtei, Zavkhan, Mongolia

and was one of the leading figures in declaration of independence of

Mongolia. He was exiled from Mongolia, the reason remains unrevealed

until today. After arriving in the US, he joined Johns Hopkins

University and founded a monastery in New Jersey.

The first Tibetan Buddhist lama to have American students was

Geshe Ngawang Wangyal, a Kalmyk-Mongolian of the

Gelug lineage, who came to the United States in 1955 and founded the "Lamaist Buddhist Monastery of America" in

New Jersey in 1958. Among his students were the future western scholars

Robert Thurman,

Jeffrey Hopkins,

Alexander Berzin and

Anne C. Klein. Other early arrivals included

Dezhung Rinpoche, a

Sakya lama who settled in

Seattle, in 1960, and

Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche, the first

Nyingma teacher in America, who arrived in the US in 1968 and established the "Tibetan Nyingma Meditation Center" in

Berkeley, California in 1969.

The best-known Tibetan Buddhist lama to live in the United States was

Chögyam Trungpa. Trungpa, part of the

Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, moved to

England in 1963, founded a temple in

Scotland, and then relocated to

Barnet, Vermont, and then

Boulder, Colorado

by 1970. He established what he named Dharmadhatu meditation centers,

eventually organized under a national umbrella group called

Vajradhatu (later to become

Shambhala International). He developed a series of secular techniques he called

Shambhala Training. Following Trungpa's death, his followers at the

Shambhala Mountain Center built the

Great Stupa of Dharmakaya, a traditional reliquary monument, near

Red Feather Lakes, Colorado consecrated in 2001.

There are four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism: the Gelug, the

Kagyu, the

Nyingma, and the

Sakya. Of these, the greatest impact in the West was made by the Gelug, led by the Dalai Lama, and the Kagyu, specifically its

Karma Kagyu branch, led by the

Karmapa. As of the early 1990s, there were several significant strands of Kagyu practice in the United States: Chögyam Trungpa's

Shambhala movement;

Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, a network of centers affiliated directly with the Karmapa's North American seat in

Woodstock, New York; a network of centers founded by

Kalu Rinpoche.

The Drikung Kagyu lineage also has an established presence in the

United States. Khenchen Konchog Gyaltsen arrived in the US in 1982 and

planted the seeds for many Drikung centers across the country. He also

paved the way for the arrival of Garchen Rinpoche, who established the

Garchen Buddhist Institute in Chino Valley, Arizona.

Diamond Way Buddhism founded by

Ole Nydahl and representing Karmapa is also active in the US.

Sravasti Abbey is the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery for Western monks and nuns in the U.S., established in Washington State by Bhikshuni

Thubten Chodron in 2003. It is situated on 300 acres of forest and meadows, 11 miles (18 km) outside of

Newport, Washington,

near the Idaho state line. It is open to visitors who want to learn

about community life in a Tibetan Buddhist monastic setting. The name

Sravasti Abbey was chosen by the

Dalai Lama. Bhikshuni

Thubten Chodron had suggested the name, as Sravasti was the place in India where the

Buddha spent 25

rains retreats (varsa

in Sanskrit and yarne in Tibetan), and communities of both nuns and

monks had resided there. This seemed auspicious to ensure the Buddha’s

teachings would be abundantly available to both male and female

monastics at the monastery.

Sravasti Abbey is notable because it is home to a growing group of fully ordained

bhikshunis

(Buddhist nuns) practicing in the Tibetan tradition. This is special

because the tradition of full ordination for women was not transmitted

from India to Tibet. Ordained women practicing in the Tibetan tradition

usually hold a novice ordination. Venerable

Thubten Chodron,

while faithfully following the teachings of her Tibetan teachers, has

arranged for her students to seek full ordination as bhikshunis in

Taiwan.

In January 2014, the Abbey, which then had seven bhikshunis and three novices, formally began its first winter

varsa

(three-month monastic retreat), which lasted until April 13, 2014. As

far as the Abbey knows, this was the first time a Western bhikshuni

sangha practicing in the Tibetan tradition had done this ritual in the

United States and in English. On April 19, 2014 the Abbey held its first

kathina ceremony to mark the end of the varsa. Also in 2014 the Abbey held its first

Pavarana rite at the end of the varsa.

In October 2015 the Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering was held

at the Abbey for the first time; it was the 21st such gathering.

In 2010 the first Tibetan Buddhist

nunnery in North America was established in Vermont, called Vajra Dakini Nunnery, offering novice ordination.

The abbot of this nunnery is an American woman named Khenmo Drolma who

is the first "bhikkhunni," a fully ordained Buddhist nun, in the

Drikung Kagyu tradition of Buddhism, having been ordained in Taiwan in 2002.

She is also the first westerner, male or female, to be installed as a

Buddhist abbot, having been installed as abbot of Vajra Dakini Nunnery

in 2004.

Theravada

Theravada is best known for

Vipassana, roughly translated as "insight meditation", which is an ancient meditative practice described in the

Pali Canon of the

Theravada

school of Buddhism and similar scriptures. Vipassana also refers to a

distinct movement which was begun in the 20th century by reformers such

as

Mahāsi Sayādaw, a

Burmese monk. Mahāsi Sayādaw was a Theravada

bhikkhu

and Vipassana is rooted in the Theravada teachings, but its goal is to

simplify ritual and other peripheral activities in order to make

meditative practice more effective and available both to monks and to

laypeople.

American Theravada Buddhists

Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery, Asalha Puja 2014

In 1965, monks from

Sri Lanka established the

Washington Buddhist Vihara in

Washington, DC,

the first Theravada monastic community in the United States. The Vihara

was accessible to English-speakers with Vipassana meditation part of

its activities. However, the direct influence of the Vipassana movement

would not reach the U.S. until a group of Americans returned there in

the early 1970s after studying with Vipassana masters in Asia.

Goldstein and Kornfield met in 1974 while teaching at the

Naropa Institute in

Colorado.

The next year, Goldstein, Kornfield, and Salzberg, who had very

recently returned from Calcutta, along with Jacqueline Schwarz, founded

the

Insight Meditation Society on an 80-acre (324,000 m²) property near

Barre, Massachusetts. IMS hosted visits by Māhāsi Sayādaw, Munindra, Ajahn Chah, and Dipa Ma. In 1981, Kornfield moved to

California, where he founded another Vipassana center,

Spirit Rock Meditation Center, in

Marin County. In 1985,

Larry Rosenberg founded the

Cambridge Insight Meditation Center in

Cambridge, Massachusetts. Another Vipassana center is the

Vipassana Metta Foundation, located on

Maui.

In 1989, the Insight Meditation Center established the

Barre Center for Buddhist Studies near the IMS headquarters, to promote scholarly investigation of Buddhism. Its director is

Mu Soeng, a former Korean Zen monk.

In 1997 Dhamma Cetiya Vihara in Boston

was founded by Ven. Gotami of Thailand, then a 10 precept nun. Ven.

Gotami received full ordination in 2000, at which time her dwelling

became America's first Theravada Buddhist bhikkhuni vihara. "Vihara"

translates as monastery or nunnery, and may be both dwelling and

community center where one or more bhikkhus or bhikkhunis offer

teachings on Buddhist scriptures, conduct traditional ceremonies, teach

meditation, offer counseling and other community services, receive alms,

and reside. More recently established Theravada bhikkhuni viharas

include: Mahapajapati Monastery

where several nuns (bhikkhunis and novices) live together in the desert

of southern California near Joshua Tree, founded by Ven. Gunasari

Bhikkhuni of Burma in 2008; Aranya Bodhi Hermitage

founded by Ven. Tathaaloka Bhikkhuni in the forest near Jenner, CA,

with Ven. Sobhana Bhikkhuni as Prioress, which opened officially in July

2010, where several bhikkhunis reside together along with trainees and

lay supporters; and Sati Saraniya

in Ontario, founded by Ven. Medhanandi in appx 2009, where two

bhikkhunis reside. (There are also quiet residences of individual

bhikkhunis where they may receive visitors and give teachings, such as

the residence of Ven. Amma Thanasanti Bhikkhuni

in 2009-2010 in Colorado Springs; and the Los Angeles residence of Ven.

Susila Bhikkhuni; and the residence of Ven. Wimala Bhikkhuni in the

mid-west.)

In 2010, in Northern California, 4 novice nuns were given the full

bhikkhuni ordination in the Thai Theravada tradition, which included the double ordination ceremony.

Bhante Gunaratana and other monks and nuns were in attendance. It was the first such ordination ever in the Western hemisphere.

S. N. Goenka

S. N. Goenka was a Burmese-born meditation teacher of the Vipassana movement. His teacher, Sayagyi

U Ba Khin

of Burma, was a contemporary of Māhāsi Sayādaw's, and taught a style of

Buddhism with similar emphasis on simplicity and accessibility to

laypeople. Goenka established a method of instruction popular in Asia

and throughout the world. In 1981, he established the

Vipassana Research Institute in

Igatpuri, India and his students built several centers in North America.

Association of American Buddhists

The

Association of American Buddhists was a group which promotes

Buddhism through publications, ordination of

monks, and classes.

Organized in 1960 by American practitioners of

Theravada,

Mahayana, and

Vajrayana

Buddhism, it does not espouse any particular school or schools of

Buddhism. It respects all Buddhist traditions as equal, and encourages

unity of Buddhism in thought and practice. It states that a different,

American, form of Buddhism is possible, and that the cultural forms

attached to the older schools of Buddhism need not necessarily be

followed by westerners.

Women and Buddhism

Rita

M. Gross, a feminist religious scholar, claims that many people

converted to Buddhism in the 1960s and '70s as an attempt to combat

traditional American values. However, in their conversion, they have

created a new form of Buddhism distinctly Western in thought and

practice.

Democratization and the rise of women in leadership positions have been

among the most influential characteristics of American Buddhism.

However, another one of these characteristics is rationalism, which has

allowed Buddhists to come to terms with the scientific and technological

advances of the 21st century. Engagement in social issues, such as

global warming, domestic violence, poverty and discrimination, has also

shaped Buddhism in America. Privatization of ritual practices into home

life has embodied Buddhism in America. The idea of living in the

“present life” rather than focusing on the future or the past is also

another characteristic of American Buddhism.

American Buddhism was able to embed these new religious ideals

into such a historically rich religious tradition and culture due to the

high conversion rate in the late 20th century. Three important factors

led to this conversion in America: the importance of religion, societal

openness, and spirituality. American culture places a large emphasis on

having a personal religious identity as a spiritual and ethical

foundation. During the 1960s and onward, society also became more open

to other religious practices outside of Protestantism, allowing more

people to explore Buddhism. People also became more interested in

spiritual and experiential religion rather than the traditional

institutional religions of the time.

The mass conversion of the 60s and 70s was also occurring

alongside the second-wave feminist movement. While many of the women who

became Buddhists at this time were drawn to its “gender neutral”

teachings, in reality Buddhism is a traditionally patriarchal religion. These two conflicting ideas caused “uneasiness” with American Buddhist women.

This uneasiness was further justified after 1983, when some male

Buddhist teachers were exposed as “sexual adventurers and abusers of

power.”

This spurred action among women in the American Buddhist community.

After much dialogue within the community, including a series of

conferences entitled “The Feminine in Buddhism,” Sandy Boucher, a

feminist-Buddhist teacher, interviewed over one hundred Buddhist women.

She determined from their experiences and her own that American

Buddhism has “the possibility for the creation of a religion fully

inclusive of women’s realities, in which women hold both institutional

and spiritual leadership.”

In recent years, there is a strong presence of women in American Buddhism, and many women are even in leadership roles.

This also may be due to the fact that American Buddhism tends to stress

democratization over the traditional hierarchical structure of Buddhism

in Asia.

One study of Theravada Buddhist centers in the U.S., however, found

that although men and women thought that Buddhist teachings were

gender-blind, there were still distinct gender roles in the

organization, including more male guest teachers and more women

volunteering as cooks and cleaners.

In 2006, for the first time in American history, a Buddhist ordination was held where an American woman (

Sister Khanti-Khema) took the

Samaneri (novice) vows with an American monk (

Bhante Vimalaramsi) presiding. This was done for the Buddhist American Forest Tradition at the Dhamma Sukha Meditation Center in Missouri.

Contemporary developments

Engaged Buddhism

Socially

engaged Buddhism has developed in Buddhism in the West. While some critics

assert the term is redundant, as it is mistaken to believe that

Buddhism in the past has not affected and been affected by the

surrounding society, others have suggested that Buddhism is sometimes

seen as too passive toward public life. This is particularly true in the

West, where almost all converts to Buddhism come to it outside of an

existing family or community tradition. Engaged Buddhism is an attempt

to apply Buddhist values to larger social problems, including

war and

environmental concerns. The term was coined by

Thich Nhat Hanh, during his years as a peace activist in

Vietnam.

The

Buddhist Peace Fellowship was founded in 1978 by

Robert Aitken, Anne Aitken, Nelson Foster, and others and received early assistance from

Gary Snyder,

Jack Kornfield, and Joanna Macy.

Another engaged Buddhist group is the

Zen Peacemaker Order, founded in 1996 by

Bernie Glassman and

Sandra Jishu Holmes.

In 2007, the American Buddhist scholar-monk, Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi, was

invited to write an editorial essay for the Buddhist magazine

Buddhadharma. In his essay, he called attention to the narrowly inward

focus of American Buddhism, which has been pursued to the neglect of the

active dimension of Buddhist compassion expressed through programs of

social engagement. Several of Ven. Bodhi’s students who read the essay

felt a desire to follow up on his suggestions. After a few rounds of

discussions, they resolved to form a Buddhist relief organization

dedicated to alleviating the suffering of the poor and disadvantaged in

the developing world. At the initial meetings, seeking a point of focus,

they decided to direct their relief efforts at the problem of global

hunger, especially by supporting local efforts by those in developing

countries to achieve self-sufficiency through improved food

productivity. Contacts were made with leaders and members of other

Buddhist communities in the greater New York area, and before long

Buddhist Global Relief emerged as an inter-denominational organization

comprising people of different Buddhist groups who share the vision of a

Buddhism actively committed to the task of alleviating social and

economic suffering.

Misconduct

A number of groups and individuals have been implicated in scandals.

Sandra Bell has analysed the scandals at Vajradhatu and the San

Francisco Zen Center and concluded that these kinds of scandals are most

likely to occur in organisations that are in transition between the

pure forms of

charismatic authority that brought them into being and more rational, corporate forms of organization".

Ford states that no one can express the "hurt and dismay" these

events brought to each center, and that the centers have in many cases

emerged stronger because they no longer depend on a "single charismatic

leader".

Robert Sharf also mentions charisma from which institutional

power is derived, and the need to balance charismatic authority with

institutional authority.

Elaborate analyses of these scandals are made by Stuart Lachs, who

mentions the uncritical acceptance of religious narratives, such as

lineages and dharma transmission, which aid in giving uncritical

charismatic powers to teachers and leaders.

Following is a partial list from reliable sources, limited to the United States and by no means all-inclusive.

Accreditation

Definitions and policies may differ greatly between different schools

or sects: for example, "many, perhaps most" Soto priests "see no

distinction between ordination and Dharma transmission". Disagreement

and misunderstanding exist on this point, among lay practitioners and

Zen teachers alike.

James Ford writes,

[S]urprising numbers of people use the titles Zen teacher, master, roshi and sensei

without any obvious connections to Zen [...] Often they obfuscate their

Zen connections, raising the very real question whether they have any

authentic relationship to the Zen world at all. In my studies I've run

across literally dozens of such cases.

James Ford claims that about eighty percent of authentic teachers in the United States belong to the

American Zen Teachers Association or the

Soto Zen Buddhist Association

and are listed on their websites. This can help a prospective student

sort out who is a "normative stream" teacher from someone who is perhaps

not, but of course twenty percent do not participate.

Demographics of Buddhism in the United States

Numbers of Buddhists

Accurate

counts of Buddhists in the United States are difficult.

Self-description has pitfalls. Because Buddhism is a cultural concept,

individuals who self-describe as Buddhists may have little knowledge or

commitment to Buddhism as a religion or practice; on the other hand,

others may be deeply involved in meditation and committed to the

Dharma, but may refuse the label "Buddhist". In the 1990s,

Robert A. F. Thurman estimated there were 5 to 6 million Buddhists in America.

In 2008, the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life Religious Landscape survey and the

American Religious Identification Survey

estimated Buddhists at 0.7 percent and 0.5 percent of the American

population, respectively. ARIS estimated that the number of adherents

rose by 170 percent between 1990 and 2000, reaching 1.2 million

followers in 2008. According to William Wilson Quinn "by all indications that remarkable rate of growth continues unabated." But according to

Robert Thurman,

Scholars are unsure whether the

reports are accurate, as Americans who might dabble in various forms of

Buddhism may not identify themselves as Buddhist on a survey. That makes

it difficult to quantify the number of Buddhists in the United States.

Others argued, in 2012, that Buddhists made up 1 percent of the American population (about three million people).

Demographics of Import Buddhists

A

sociological survey conducted in 1999 found that relative to the US

population as a whole, import Buddhists (i.e., those who are not

Buddhist by birth) are proportionately more likely to be white, upper

middle class, highly educated, and left-leaning in their political

views. In terms of race, only 10% of survey respondents indicated they

were a race other than white, a matter that has been cause of some

concern among Buddhist leaders. Nearly a third of the respondents were

college graduates, and more than half held advanced degrees.

Politically, 60% identified themselves as

Democrats, and

Green Party affiliations outnumbered

Republicans by 3 to 1. Import Buddhists were also proportionately more likely to have come from

Catholic, and especially

Jewish

backgrounds. More than half of these adherents came to Buddhism through

reading books on the topic, with the rest coming by way of martial arts

and friends or acquaintances. The average age of the respondents was

46. Daily meditation was their most commonly cited Buddhist practice,

with most meditating 30 minutes a day or more.

In 2015 a Pew Foundation survey found 67% of American Buddhists were raised in a religion other than Buddhism. 61% said their spouse has a religion other than Buddhism.

The survey was conducted only in English and Spanish, and may

under-estimate Buddhist immigrants who speak Asian languages. A 2012 Pew

study found Buddhism is practiced by 15% of surveyed Chinese Americans,

6% of Koreans, 25% of Japanese, 43% of Vietnamese and 1% of Filipinos.

Ethnic divide

Only

about a third (32%) of Buddhists in the United States are Asian; a

majority (53%) are white. Buddhism in the America is primarily made up

of native-born adherents, whites and converts.

Discussion about Buddhism in America has sometimes focused on the

issue of the visible ethnic divide separating ethnic Buddhist

congregations from import Buddhist groups.

Although many Zen and Tibetan Buddhist temples were founded by Asians,

they now attract fewer Asian-Americans. With the exception of

Sōka Gakkai,

almost all active Buddhist groups in America are either ethnic or

import Buddhism based on the demographics of their membership. There is

often limited contact between Buddhists of different ethnic groups.

However, the cultural divide should not necessarily be seen as

pernicious. It is often argued that the differences between Buddhist

groups arise benignly from the differing needs and interests of those

involved. Convert Buddhists tend to be interested in

meditation and

philosophy,

in some cases eschewing the trappings of religiosity altogether. On the

other hand, for immigrants and their descendants, preserving tradition

and maintaining a social framework assume a much greater relative

importance, making their approach to religion naturally more

conservative. Further, based on a survey of Asian-American Buddhists in

San Francisco, "many Asian-American Buddhists view non-Asian Buddhism as

still in a formative, experimental stage" and yet they believe that it

"could eventually mature into a religious expression of exceptional

quality".

Additional questions come from the demographics within import

Buddhism. The majority of American converts practicing at Buddhist

centers are white, often from

Christian or

Jewish

backgrounds. Only Sōka Gakkai has attracted significant numbers of

African-American or Latino members. A variety of ideas have been

broached regarding the nature, causes, and significance of this racial

uniformity. Journalist Clark Strand noted

- …that it has tried to recruit [African-Americans] at all makes Sōka Gakkai International utterly unique in American Buddhism.

Strand, writing for

Tricycle

(an American Buddhist journal) in 2004, notes that SGI has specifically

targeted African-Americans, Latinos and Asians, and other writers have

noted that this approach has begun to spread, with Vipassana and

Theravada retreats aimed at non-white practitioners led by a handful of

specific teachers.

A question is the degree of importance ascribed to

discrimination, which is suggested to be mostly unconscious, on the part

of white converts toward potential minority converts. To some extent, the

racial divide indicates a class divide, because convert Buddhists tend to be more educated. Among African American Buddhists who commented on the dynamics of the racial divide in convert Buddhism are

Jan Willis and

Charles R. Johnson.

A Pew study shows that Americans tend to be less biased towards

Buddhists when compared to other religions, such as Christianity, to

which 18% of people were biased, when only 14% were biased towards

Buddhists. American Buddhists are often not raised as Buddhists, with

32% of American Buddhists being raised Protestant, and 22% being raised

Catholic, which means that over half of the American Buddhists were

converted at some point in time. Also, Buddhism has had to adapt to

America in order to garner more followers so that the concept would not

seem so foreign, so they adopted "Catholic" words such as "worship" and

"churches."

Buddhist education in the United States

The

University of the West is affiliated with Hsi Lai Temple and was previously Hsi Lai University.

Soka University of America,

in Aliso Viejo California, was founded by the Sōka Gakkai as a secular

school committed to philosophic Buddhism. The City of Ten Thousand

Buddhas is the site of

Dharma Realm Buddhist University, a four-year college teaching courses primarily related to Buddhism but including some general-interest subjects. The

Institute of Buddhist Studies

in Berkeley, California, in addition to offering a master's degree in

Buddhist Studies acts as the ministerial training arm of the Buddhist

Churches of America and is affiliated with the

Graduate Theological Union. The school moved into the Jodo Shinshu Center in Berkeley.

The first Buddhist

high school in the United States,

Developing Virtue Secondary School, was founded in 1981 by the

Dharma Realm Buddhist Association at their branch monastery in the

City of Ten Thousand Buddhas in

Ukiah, California. In 1997, the Purple Lotus Buddhist School offered elementary-level classes in

Union City, California, affiliated with the

True Buddha School; it added a middle school in 1999 and a high school in 2001. Another Buddhist high school, Tinicum Art and Science now The Lotus School of Liberal Arts |url=

http://Lotusla.org, which combines Zen practice and traditional liberal arts, opened in

Ottsville, Pennsylvania in 1998. It is associated informally with the World Shim Gum Do Association in Boston. The

Pacific Buddhist Academy opened in

Honolulu,

Hawaii in 2003. It shares a campus with the

Hongwanji Mission School, an elementary and middle school; both schools affiliated with the Honpa Hongwanji Jodo Shinshu mission.

Juniper Foundation, founded in 2003, holds that Buddhist methods must become integrated into modern culture just as they were in other cultures. Juniper Foundation calls its approach "Buddhist training for modern life"

and it emphasizes meditation, balancing emotions, cultivating

compassion and developing insight as four building blocks of Buddhist

training.