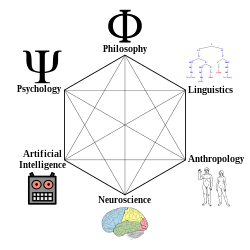

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition (in a broad sense). Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include perception, memory, attention, reasoning, language, and emotion. To understand these faculties, cognitive scientists borrow from fields such as psychology, philosophy, artificial intelligence, neuroscience, linguistics, and anthropology. The typical analysis of cognitive science spans many levels of organization, from learning and decision-making to logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization. One of the fundamental concepts of cognitive science is that "thinking can best be understood in terms of representational structures in the mind and computational procedures that operate on those structures."

History

The cognitive sciences began as an intellectual movement in the 1950s, called the cognitive revolution. Cognitive science has a prehistory traceable back to ancient Greek philosophical texts (see Plato's Meno and Aristotle's De Anima).

The modern culture of cognitive science can be traced back to the early cyberneticists in the 1930s and 1940s, such as Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts, who sought to understand the organizing principles of the mind. McCulloch and Pitts developed the first variants of what are now known as artificial neural networks, models of computation inspired by the structure of biological neural networks.

Another precursor was the early development of the theory of computation and the digital computer in the 1940s and 1950s. Kurt Gödel, Alonzo Church, Claude Shannon, Alan Turing, and John von Neumann were instrumental in these developments. The modern computer, or Von Neumann machine, would play a central role in cognitive science, both as a metaphor for the mind, and as a tool for investigation.

The first instance of cognitive science experiments being done at an academic institution took place at MIT Sloan School of Management, established by J.C.R. Licklider working within the psychology department and conducting experiments using computer memory as models for human cognition. In 1959, Noam Chomsky published a scathing review of B. F. Skinner's book Verbal Behavior. At the time, Skinner's behaviorist paradigm dominated the field of psychology within the United States. Most psychologists focused on functional relations between stimulus and response, without positing internal representations. Chomsky argued that in order to explain language, we needed a theory like generative grammar, which not only attributed internal representations but characterized their underlying order.

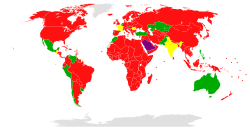

The term cognitive science was coined by Christopher Longuet-Higgins in his 1973 commentary on the Lighthill report, which concerned the then-current state of artificial intelligence research. In the same decade, the journal Cognitive Science and the Cognitive Science Society were founded. The founding meeting of the Cognitive Science Society was held at the University of California, San Diego in 1979, which resulted in cognitive science becoming an internationally visible enterprise. In 1972, Hampshire College started the first undergraduate education program in Cognitive Science, led by Neil Stillings. In 1982, with assistance from Professor Stillings, Vassar College became the first institution in the world to grant an undergraduate degree in Cognitive Science. In 1986, the first Cognitive Science Department in the world was founded at the University of California, San Diego.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, as access to computers increased, artificial intelligence research expanded. Researchers such as Marvin Minsky would write computer programs in languages such as LISP to attempt to formally characterize the steps that human beings went through, for instance, in making decisions and solving problems, in the hope of better understanding human thought, and also in the hope of creating artificial minds. This approach is known as "symbolic AI".

Eventually the limits of the symbolic AI research program became apparent. For instance, it seemed to be unrealistic to comprehensively list human knowledge in a form usable by a symbolic computer program. The late 80s and 90s saw the rise of neural networks and connectionism as a research paradigm. Under this point of view, often attributed to James McClelland and David Rumelhart, the mind could be characterized as a set of complex associations, represented as a layered network. Critics argue that there are some phenomena which are better captured by symbolic models, and that connectionist models are often so complex as to have little explanatory power. Recently symbolic and connectionist models have been combined, making it possible to take advantage of both forms of explanation. While both connectionism and symbolic approaches have proven useful for testing various hypotheses and exploring approaches to understanding aspects of cognition and lower level brain functions, neither are biologically realistic and therefore, both suffer from a lack of neuroscientific plausibility. Connectionism has proven useful for exploring computationally how cognition emerges in development and occurs in the human brain, and has provided alternatives to strictly domain-specific / domain general approaches. For example, scientists such as Jeff Elman, Liz Bates, and Annette Karmiloff-Smith have posited that networks in the brain emerge from the dynamic interaction between them and environmental input.

Recent developments in quantum computation, including the ability to run quantum circuits on quantum computers such as IBM Quantum Platform, has accelerated work using elements from quantum mechanics in cognitive models.

Principles

Levels of analysis

A central tenet of cognitive science is that a complete understanding of the mind/brain cannot be attained by studying only a single level. An example would be the problem of remembering a phone number and recalling it later. One approach to understanding this process would be to study behavior through direct observation, or naturalistic observation. A person could be presented with a phone number and be asked to recall it after some delay of time; then the accuracy of the response could be measured. Another approach to measure cognitive ability would be to study the firings of individual neurons while a person is trying to remember the phone number. Neither of these experiments on its own would fully explain how the process of remembering a phone number works. Even if the technology to map out every neuron in the brain in real-time were available and it were known when each neuron fired it would still be impossible to know how a particular firing of neurons translates into the observed behavior. Thus an understanding of how these two levels relate to each other is imperative. Francisco Varela, in The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, argues that "the new sciences of the mind need to enlarge their horizon to encompass both lived human experience and the possibilities for transformation inherent in human experience". On the classic cognitivist view, this can be provided by a functional level account of the process. Studying a particular phenomenon from multiple levels creates a better understanding of the processes that occur in the brain to give rise to a particular behavior. Marr gave a famous description of three levels of analysis:

- The computational theory, specifying the goals of the computation;

- Representation and algorithms, giving a representation of the inputs and outputs and the algorithms which transform one into the other; and

- The hardware implementation, or how algorithm and representation may be physically realized.

Interdisciplinary nature

Cognitive science is an interdisciplinary field with contributors from various fields, including psychology, neuroscience, linguistics, philosophy of mind, computer science, anthropology and biology. Cognitive scientists work collectively in hope of understanding the mind and its interactions with the surrounding world much like other sciences do. The field regards itself as compatible with the physical sciences and uses the scientific method as well as simulation or modeling, often comparing the output of models with aspects of human cognition. Similarly to the field of psychology, there is some doubt whether there is a unified cognitive science, which have led some researchers to prefer 'cognitive sciences' in plural.

Many, but not all, who consider themselves cognitive scientists hold a functionalist view of the mind—the view that mental states and processes should be explained by their function – what they do. According to the multiple realizability account of functionalism, even non-human systems such as robots and computers can be ascribed as having cognition.

Cognitive science, the term

The term "cognitive" in "cognitive science" is used for "any kind of mental operation or structure that can be studied in precise terms" (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999). This conceptualization is very broad, and should not be confused with how "cognitive" is used in some traditions of analytic philosophy, where "cognitive" has to do only with formal rules and truth-conditional semantics.

The earliest entries for the word "cognitive" in the OED take it to mean roughly "pertaining to the action or process of knowing". The first entry, from 1586, shows the word was at one time used in the context of discussions of Platonic theories of knowledge. Most in cognitive science, however, presumably do not believe their field is the study of anything as certain as the knowledge sought by Plato.

Scope

Cognitive science is a large field, and covers a wide array of topics on cognition. However, it should be recognized that cognitive science has not always been equally concerned with every topic that might bear relevance to the nature and operation of minds. Classical cognitivists have largely de-emphasized or avoided social and cultural factors, embodiment, emotion, consciousness, animal cognition, and comparative and evolutionary psychologies. However, with the decline of behaviorism, internal states such as affects and emotions, as well as awareness and covert attention became approachable again. For example, situated and embodied cognition theories take into account the current state of the environment as well as the role of the body in cognition. With the newfound emphasis on information processing, observable behavior was no longer the hallmark of psychological theory, but the modeling or recording of mental states.

Below are some of the main topics that cognitive science is concerned with; see List of cognitive science topics for a more exhaustive list.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) involves the study of cognitive phenomena in machines. One of the practical goals of AI is to implement aspects of human intelligence in computers. Computers are also widely used as a tool with which to study cognitive phenomena. Computational modeling uses simulations to study how human intelligence may be structured. (See § Computational modeling.)

There is some debate in the field as to whether the mind is best viewed as a huge array of small but individually feeble elements (i.e. neurons), or as a collection of higher-level structures such as symbols, schemes, plans, and rules. The former view uses connectionism to study the mind, whereas the latter emphasizes symbolic artificial intelligence. One way to view the issue is whether it is possible to accurately simulate a human brain on a computer without accurately simulating the neurons that make up the human brain.

Attention

Attention is the selection of important information. The human mind is bombarded with millions of stimuli and it must have a way of deciding which of this information to process. Attention is sometimes seen as a spotlight, meaning one can only shine the light on a particular set of information. Experiments that support this metaphor include the dichotic listening task (Cherry, 1957) and studies of inattentional blindness (Mack and Rock, 1998). In the dichotic listening task, subjects are bombarded with two different messages, one in each ear, and told to focus on only one of the messages. At the end of the experiment, when asked about the content of the unattended message, subjects cannot report it.

The psychological construct of attention is sometimes confused with the concept of intentionality due to some degree of semantic ambiguity in their definitions. At the beginning of experimental research on attention, Wilhelm Wundt defined this term as "that psychical process, which is operative in the clear perception of the narrow region of the content of consciousness." His experiments showed the limits of attention in space and time, which were 3-6 letters during an exposition of 1/10 s. Because this notion develops within the framework of the original meaning during a hundred years of research, the definition of attention would reflect the sense when it accounts for the main features initially attributed to this term – it is a process of controlling thought that continues over time. While intentionality is the power of minds to be about something, attention is the concentration of awareness on some phenomenon during a period of time, which is necessary to elevate the clear perception of the narrow region of the content of consciousness and which is feasible to control this focus in mind.

The significance of knowledge about the scope of attention for studying cognition is that it defines the intellectual functions of cognition such as apprehension, judgment, reasoning, and working memory. The development of attention scope increases the set of faculties responsible for the mind relies on how it perceives, remembers, considers, and evaluates in making decisions. The ground of this statement is that the more details (associated with an event) the mind may grasp for their comparison, association, and categorization, the closer apprehension, judgment, and reasoning of the event are in accord with reality. According to Latvian professor Sandra Mihailova and professor Igor Val Danilov, the more elements of the phenomenon (or phenomena ) the mind can keep in the scope of attention simultaneously, the more significant number of reasonable combinations within that event it can achieve, enhancing the probability of better understanding features and particularity of the phenomenon (phenomena). For example, three items in the focal point of consciousness yield six possible combinations (3 factorial) and four items – 24 (4 factorial) combinations. The number of reasonable combinations becomes significant in the case of a focal point with six items with 720 possible combinations (6 factorial).

Bodily processes related to cognition

Embodied cognition approaches to cognitive science emphasize the role of body and environment in cognition. This includes both neural and extra-neural bodily processes, and factors that range from affective and emotional processes, to posture, motor control, proprioception, and kinaesthesis, to autonomic processes that involve heartbeat and respiration, to the role of the enteric gut microbiome. It also includes accounts of how the body engages with or is coupled to social and physical environments. 4E cognition includes a broad range of views about brain-body-environment interaction, from causal embeddedness to stronger claims about how the mind extends to include tools and instruments, as well as the role of social interactions, action-oriented processes, and affordances. 4E theories range from those closer to classic cognitivism (so-called "weak" embodied cognition) to stronger extended and enactive versions that are sometimes referred to as radical embodied cognitive science.

A hypothesis of pre-perceptual multimodal integration supports embodied cognition approaches and converges two competing naturalist and constructivist viewpoints about cognition and the development of emotions. According to this hypothesis supported by empirical data, cognition and emotion development are initiated by the association of affective cues with stimuli responsible for triggering the neuronal pathways of simple reflexes. This pre-perceptual multimodal integration can succeed owing to neuronal coherence in mother-child dyads beginning from pregnancy. These cognitive-reflex and emotion-reflex stimuli conjunctions further form simple innate neuronal assemblies, shaping the cognitive and emotional neuronal patterns in statistical learning that are continuously connected with the neuronal pathways of reflexes.

Knowledge and processing of language

The ability to learn and understand language is an extremely complex process. Language is acquired within the first few years of life, and all humans under normal circumstances are able to acquire language proficiently. A major driving force in the theoretical linguistic field is discovering the nature that language must have in the abstract in order to be learned in such a fashion. Some of the driving research questions in studying how the brain itself processes language include: (1) To what extent is linguistic knowledge innate or learned?, (2) Why is it more difficult for adults to acquire a second-language than it is for infants to acquire their first-language?, and (3) How are humans able to understand novel sentences?

The study of language processing ranges from the investigation of the sound patterns of speech to the meaning of words and whole sentences. Linguistics often divides language processing into orthography, phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Many aspects of language can be studied from each of these components and from their interaction.

The study of language processing in cognitive science is closely tied to the field of linguistics. Linguistics was traditionally studied as a part of the humanities, including studies of history, art and literature. In the last fifty years or so, more and more researchers have studied knowledge and use of language as a cognitive phenomenon, the main problems being how knowledge of language can be acquired and used, and what precisely it consists of. Linguists have found that, while humans form sentences in ways apparently governed by very complex systems, they are remarkably unaware of the rules that govern their own speech. Thus linguists must resort to indirect methods to determine what those rules might be, if indeed rules as such exist. In any event, if speech is indeed governed by rules, they appear to be opaque to any conscious consideration.

Learning and development

Learning and development are the processes by which we acquire knowledge and information over time. Infants are born with little or no knowledge (depending on how knowledge is defined), yet they rapidly acquire the ability to use language, walk, and recognize people and objects. Research in learning and development aims to explain the mechanisms by which these processes might take place.

A major question in the study of cognitive development is the extent to which certain abilities are innate or learned. This is often framed in terms of the nature and nurture debate. The nativist view emphasizes that certain features are innate to an organism and are determined by its genetic endowment. The empiricist view, on the other hand, emphasizes that certain abilities are learned from the environment. Although clearly both genetic and environmental input is needed for a child to develop normally, considerable debate remains about how genetic information might guide cognitive development. In the area of language acquisition, for example, some (such as Steven Pinker) have argued that specific information containing universal grammatical rules must be contained in the genes, whereas others (such as Jeffrey Elman and colleagues in Rethinking Innateness) have argued that Pinker's claims are biologically unrealistic. They argue that genes determine the architecture of a learning system, but that specific "facts" about how grammar works can only be learned as a result of experience.

Memory

Memory allows us to store information for later retrieval. Memory is often thought of as consisting of both a long-term and short-term store. Long-term memory allows us to store information over prolonged periods (days, weeks, years). We do not yet know the practical limit of long-term memory capacity. Short-term memory allows us to store information over short time scales (seconds or minutes).

Memory is also often grouped into declarative and procedural forms. Declarative memory—grouped into subsets of semantic and episodic forms of memory—refers to our memory for facts and specific knowledge, specific meanings, and specific experiences (e.g. "Are apples food?", or "What did I eat for breakfast four days ago?"). Procedural memory allows us to remember actions and motor sequences (e.g. how to ride a bicycle) and is often dubbed implicit knowledge or memory .

Cognitive scientists study memory just as psychologists do, but tend to focus more on how memory bears on cognitive processes, and the interrelationship between cognition and memory. One example of this could be, what mental processes does a person go through to retrieve a long-lost memory? Or, what differentiates between the cognitive process of recognition (seeing hints of something before remembering it, or memory in context) and recall (retrieving a memory, as in "fill-in-the-blank")?

Perception and action

Perception is the ability to take in information via the senses, and process it in some way. Vision and hearing are two dominant senses that allow us to perceive the environment. Some questions in the study of visual perception, for example, include: (1) How are we able to recognize objects?, (2) Why do we perceive a continuous visual environment, even though we only see small bits of it at any one time? One tool for studying visual perception is by looking at how people process optical illusions. The image on the right of a Necker cube is an example of a bistable percept, that is, the cube can be interpreted as being oriented in two different directions.

The study of haptic (tactile), olfactory, and gustatory stimuli also fall into the domain of perception.

Action is taken to refer to the output of a system. In humans, this is accomplished through motor responses. Spatial planning and movement, speech production, and complex motor movements are all aspects of action.

Consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of states or objects either internal to one's self or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of explanations, analyses, and debate among philosophers, scientists, and theologians. Opinions differ about what exactly needs to be studied, or can even be considered consciousness. In some explanations, it is synonymous with mind, and at other times, an aspect of it.

In the past, consciousness meant one's "inner life": the world of introspection, private thought, imagination, and volition. Today, it often includes any kind of cognition, experience, feeling, or perception. It may be awareness, awareness of awareness, metacognition, or self-awareness, either continuously changing or not. There is also a medical definition that helps, for example, to discern "coma" from other states. The disparate range of research, notions, and speculations raises some curiosity about whether the right questions are being asked.

Examples of the range of descriptions, definitions and explanations are: ordered distinction between self and environment, simple wakefulness, one's sense of selfhood or soul explored by "looking within", being a metaphorical "stream" of contents, or being a mental state, mental event, or mental process of the brain.Research methods

Many different methodologies are used to study cognitive science. As the field is highly interdisciplinary, research often cuts across multiple areas of study, drawing on research methods from psychology, neuroscience, computer science and systems theory.

Behavioral experiments

In order to have a description of what constitutes intelligent behavior, one must study behavior itself. This type of research is closely tied to that in cognitive psychology and psychophysics. By measuring behavioral responses to different stimuli, one can understand something about how those stimuli are processed. Lewandowski & Strohmetz (2009) reviewed a collection of innovative uses of behavioral measurement in psychology including behavioral traces, behavioral observations, and behavioral choice. Behavioral traces are pieces of evidence that indicate behavior occurred, but the actor is not present (e.g., litter in a parking lot or readings on an electric meter). Behavioral observations involve the direct witnessing of the actor engaging in the behavior (e.g., watching how close a person sits next to another person). Behavioral choices are when a person selects between two or more options (e.g., voting behavior, choice of a punishment for another participant).

- Reaction time. The time between the presentation of a stimulus and an appropriate response can indicate differences between two cognitive processes, and can indicate some things about their nature. For example, if in a search task the reaction times vary proportionally with the number of elements, then it is evident that this cognitive process of searching involves serial instead of parallel processing.

- Psychophysical responses. Psychophysical experiments are an

old psychological technique, which has been adopted by cognitive

psychology. They typically involve making judgments of some physical

property, e.g. the loudness of a sound. Correlation of subjective scales

between individuals can show cognitive or sensory biases as compared to

actual physical measurements. Some examples include:

- sameness judgments for colors, tones, textures, etc.

- threshold differences for colors, tones, textures, etc.

- Eye tracking. This methodology is used to study a variety of cognitive processes, most notably visual perception and language processing. The fixation point of the eyes is linked to an individual's focus of attention. Thus, by monitoring eye movements, we can study what information is being processed at a given time. Eye tracking allows us to study cognitive processes on extremely short time scales. Eye movements reflect online decision making during a task, and they provide us with some insight into the ways in which those decisions may be processed.

Brain imaging

Brain imaging involves analyzing activity within the brain while performing various tasks. This allows us to link behavior and brain function to help understand how information is processed. Different types of imaging techniques vary in their temporal (time-based) and spatial (location-based) resolution. Brain imaging is often used in cognitive neuroscience.

- Single-photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography. SPECT and PET use radioactive isotopes, which are injected into the subject's bloodstream and taken up by the brain. By observing which areas of the brain take up the radioactive isotope, we can see which areas of the brain are more active than other areas. PET has similar spatial resolution to fMRI, but it has extremely poor temporal resolution.

- Electroencephalography. EEG measures the electrical fields generated by large populations of neurons in the cortex by placing a series of electrodes on the scalp of the subject. This technique has an extremely high temporal resolution, but a relatively poor spatial resolution.

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging. fMRI measures the relative amount of oxygenated blood flowing to different parts of the brain. More oxygenated blood in a particular region is assumed to correlate with an increase in neural activity in that part of the brain. This allows us to localize particular functions within different brain regions. fMRI has moderate spatial and temporal resolution.

- Optical imaging. This technique uses infrared transmitters and receivers to measure the amount of light reflectance by blood near different areas of the brain. Since oxygenated and deoxygenated blood reflects light by different amounts, we can study which areas are more active (i.e., those that have more oxygenated blood). Optical imaging has moderate temporal resolution, but poor spatial resolution. It also has the advantage that it is extremely safe and can be used to study infants' brains.

- Magnetoencephalography. MEG measures magnetic fields resulting from cortical activity. It is similar to EEG, except that it has improved spatial resolution since the magnetic fields it measures are not as blurred or attenuated by the scalp, meninges and so forth as the electrical activity measured in EEG is. MEG uses SQUID sensors to detect tiny magnetic fields.

Computational modeling

Computational models require a mathematically and logically formal representation of a problem. Computer models are used in the simulation and experimental verification of different specific and general properties of intelligence. Computational modeling can help us understand the functional organization of a particular cognitive phenomenon. Approaches to cognitive modeling can be categorized as: (1) symbolic, on abstract mental functions of an intelligent mind by means of symbols; (2) subsymbolic, on the neural and associative properties of the human brain; and (3) across the symbolic–subsymbolic border, including hybrid.

- Symbolic modeling evolved from the computer science paradigms using the technologies of knowledge-based systems, as well as a philosophical perspective (e.g. "Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence" (GOFAI)). They were developed by the first cognitive researchers and later used in information engineering for expert systems. Since the early 1990s it was generalized in systemics for the investigation of functional human-like intelligence models, such as personoids, and, in parallel, developed as the SOAR environment. Recently, especially in the context of cognitive decision-making, symbolic cognitive modeling has been extended to the socio-cognitive approach, including social and organizational cognition, interrelated with a sub-symbolic non-conscious layer.

- Subsymbolic modeling includes connectionist/neural network models. Connectionism relies on the idea that the mind/brain is composed of simple nodes and its problem-solving capacity derives from the connections between them. Neural nets are textbook implementations of this approach. Some critics of this approach feel that while these models approach biological reality as a representation of how the system works, these models lack explanatory powers because, even in systems endowed with simple connection rules, the emerging high complexity makes them less interpretable at the connection-level than they apparently are at the macroscopic level.

- Other approaches gaining in popularity include (1) dynamical systems theory, (2) mapping symbolic models onto connectionist models (Neural-symbolic integration or hybrid intelligent systems), and (3) and Bayesian models, which are often drawn from machine learning.

All the above approaches tend either to be generalized to the form of integrated computational models of a synthetic/abstract intelligence (i.e. cognitive architecture) in order to be applied to the explanation and improvement of individual and social/organizational decision-making and reasoning or to focus on single simulative programs (or microtheories/"middle-range" theories) modelling specific cognitive faculties (e.g. vision, language, categorization etc.).

Neurobiological methods

Research methods borrowed directly from neuroscience and neuropsychology can also help us to understand aspects of intelligence. These methods allow us to understand how intelligent behavior is implemented in a physical system.

Key findings

Cognitive science has given rise to models of human cognitive bias and risk perception, and has been influential in the development of behavioral finance, part of economics. It has also given rise to a new theory of the philosophy of mathematics (related to denotational mathematics), and many theories of artificial intelligence, persuasion and coercion. It has made its presence known in the philosophy of language and epistemology as well as constituting a substantial wing of modern linguistics. Fields of cognitive science have been influential in understanding the brain's particular functional systems (and functional deficits) ranging from speech production to auditory processing and visual perception. It has made progress in understanding how damage to particular areas of the brain affect cognition, and it has helped to uncover the root causes and results of specific dysfunction, such as dyslexia, anopsia, and hemispatial neglect.

Notable researchers

| Name | Year of birth | Year of contribution | Contribution(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| David Chalmers | 1966 | 1995 | Dualism, hard problem of consciousness |

| Daniel Dennett | 1942 | 1987 | Offered a computational systems perspective (multiple drafts model) |

| John Searle | 1932 | 1980 | Chinese room |

| Douglas Hofstadter | 1945 | 1979 | Gödel, Escher, Bach |

| Jerry Fodor | 1935 | 1968, 1975 | Functionalism |

| Alan Baddeley | 1934 | 1974 | Baddeley's model of working memory |

| Marvin Minsky | 1927 | 1970s, early 1980s | Wrote computer programs in languages such as LISP to attempt to formally characterize the steps that human beings go through, such as making decisions and solving problems |

| Christopher Longuet-Higgins | 1923 | 1973 | Coined the term cognitive science |

| Noam Chomsky | 1928 | 1959 | Published a review of B.F. Skinner's book Verbal Behavior which began cognitivism against then-dominant behaviorism |

| George Miller | 1920 | 1956 | Wrote about the capacities of human thinking through mental representations |

| Herbert Simon | 1916 | 1956 | Co-created Logic Theory Machine and General Problem Solver with Allen Newell, EPAM (Elementary Perceiver and Memorizer) theory, organizational decision-making |

| John McCarthy | 1927 | 1955 | Coined the term artificial intelligence and organized the famous Dartmouth conference in Summer 1956, which started AI as a field |

| McCulloch and Pitts | 1930s–1940s | Developed early artificial neural networks | |

| Lila R. Gleitman | 1929 | 1970s-2010s | Wide-ranging contributions to understanding the cognition of language acquisition, including syntactic bootstrapping theory |

| Eleanor Rosch | 1938 | 1976 | Development of the Prototype Theory of categorisation |

| Philip N. Johnson-Laird | 1936 | 1980 | Introduced the idea of mental models in cognitive science |

| Dedre Gentner | 1944 | 1983 | Development of the Structure-mapping Theory of analogical reasoning |

| Allen Newell | 1927 | 1990 | Development of the field of Cognitive architecture in cognitive modelling and artificial intelligence |

| Annette Karmiloff-Smith | 1938 | 1992 | Integrating neuroscience and computational modelling into theories of cognitive development |

| David Marr (neuroscientist) | 1945 | 1990 | Proponent of the Three-Level Hypothesis of levels of analysis of computational systems |

| Peter Gärdenfors | 1949 | 2000 | Creator of the conceptual space framework used in cognitive modelling and artificial intelligence. |

| Linda B. Smith | 1951 | 1993 | Together with Esther Thelen, created a dynamical systems approach to understanding cognitive development |

Some of the more recognized names in cognitive science are usually either the most controversial or the most cited. Within philosophy, some familiar names include Daniel Dennett, who writes from a computational systems perspective, John Searle, known for his controversial Chinese room argument, and Jerry Fodor, who advocates functionalism.

Others include David Chalmers, who advocates Dualism and is also known for articulating the hard problem of consciousness, and Douglas Hofstadter, famous for writing Gödel, Escher, Bach, which questions the nature of words and thought.

In the realm of linguistics, Noam Chomsky and George Lakoff have been influential (both have also become notable as political commentators). In artificial intelligence, Marvin Minsky, Herbert A. Simon, and Allen Newell are prominent.

Popular names in the discipline of psychology include George A. Miller, James McClelland, Philip Johnson-Laird, Lawrence Barsalou, Vittorio Guidano, Howard Gardner and Steven Pinker. Anthropologists Dan Sperber, Edwin Hutchins, Bradd Shore, James Wertsch and Scott Atran, have been involved in collaborative projects with cognitive and social psychologists, political scientists and evolutionary biologists in attempts to develop general theories of culture formation, religion, and political association.

Computational theories (with models and simulations) have also been developed, by David Rumelhart, James McClelland and Philip Johnson-Laird.

Epistemics

Epistemics is a term coined in 1969 by the University of Edinburgh with the foundation of its School of Epistemics. Epistemics is to be distinguished from epistemology in that epistemology is the philosophical theory of knowledge, whereas epistemics signifies the scientific study of knowledge.

Christopher Longuet-Higgins has defined it as "the construction of formal models of the processes (perceptual, intellectual, and linguistic) by which knowledge and understanding are achieved and communicated." In his 1978 essay "Epistemics: The Regulative Theory of Cognition", Alvin I. Goldman claims to have coined the term "epistemics" to describe a reorientation of epistemology. Goldman maintains that his epistemics is continuous with traditional epistemology and the new term is only to avoid opposition. Epistemics, in Goldman's version, differs only slightly from traditional epistemology in its alliance with the psychology of cognition; epistemics stresses the detailed study of mental processes and information-processing mechanisms that lead to knowledge or beliefs.

In the mid-1980s, the School of Epistemics was renamed as The Centre for Cognitive Science (CCS). In 1998, CCS was incorporated into the University of Edinburgh's School of Informatics.

Binding problem in cognitive science

One of the core aims of cognitive science is to achieve an integrated theory of cognition. This requires integrative mechanisms explaining how the information processing that occurs simultaneously in spatially segregated (sub-)cortical areas in the brain is coordinated and bound together to give rise to coherent perceptual and symbolic representations. One approach is to solve this "Binding problem" (that is, the problem of dynamically representing conjunctions of informational elements, from the most basic perceptual representations ("feature binding") to the most complex cognitive representations, like symbol structures ("variable binding")), by means of integrative synchronization mechanisms. In other words, one of the coordinating mechanisms appears to be the temporal (phase) synchronization of neural activity based on dynamical self-organizing processes in neural networks, described by the Binding-by-synchrony (BBS) Hypothesis from neurophysiology. Connectionist cognitive neuroarchitectures have been developed that use integrative synchronization mechanisms to solve this binding problem in perceptual cognition and in language cognition. In perceptual cognition the problem is to explain how elementary object properties and object relations, like the object color or the object form, can be dynamically bound together or can be integrated to a representation of this perceptual object by means of a synchronization mechanism ("feature binding", "feature linking"). In language cognition the problem is to explain how semantic concepts and syntactic roles can be dynamically bound together or can be integrated to complex cognitive representations like systematic and compositional symbol structures and propositions by means of a synchronization mechanism ("variable binding") (see also the "Symbolism vs. connectionism debate" in connectionism).

However, despite significant advances in understanding the integrated theory of cognition (specifically the Binding problem), the debate on this issue of beginning cognition is still in progress. From the different perspectives noted above, this problem can be reduced to the issue of how organisms at the simple reflexes stage of development overcome the threshold of the environmental chaos of sensory stimuli: electromagnetic waves, chemical interactions, and pressure fluctuations. The so-called Primary Data Entry (PDE) thesis poses doubts about the ability of such an organism to overcome this cue threshold on its own. In terms of mathematical tools, the PDE thesis underlines the insuperable high threshold of the cacophony of environmental stimuli (the stimuli noise) for young organisms at the onset of life. It argues that the temporal (phase) synchronization of neural activity based on dynamical self-organizing processes in neural networks, any dynamical bound together or integration to a representation of the perceptual object by means of a synchronization mechanism can not help organisms in distinguishing relevant cue (informative stimulus) for overcome this noise threshold.