A supercritical fluid (SCF) is a substance at a temperature and pressure above its critical point, where distinct liquid and gas phases do not exist, but below the pressure required to compress it into a solid. It can effuse through porous solids like a gas, overcoming the mass transfer limitations that slow liquid transport through such materials. SCFs are superior to gases in their ability to dissolve materials like liquids or solids. Near the critical point, small changes in pressure or temperature result in large changes in density, allowing many properties of a supercritical fluid to be "fine-tuned".

Supercritical fluids occur in the atmospheres of the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, the terrestrial planet Venus, and probably in those of the ice giants Uranus and Neptune. Supercritical water is found on Earth, such as the water issuing from black smokers, a type of hydrothermal vent. SCFs are used as a substitute for organic solvents in a range of industrial and laboratory processes, most commonly carbon dioxide for decaffeination and water for steam boilers for power generation. Some substances are soluble in the supercritical state of a solvent (e.g., carbon dioxide) but insoluble in the gaseous or liquid state—or vice versa. This can be used to extract a substance and transport it elsewhere in solution before depositing it in the desired place by allowing or inducing a phase transition in the solvent.

Properties

Supercritical fluids generally have properties between those of a gas and a liquid. In Table 1, the critical properties are shown for some substances that are commonly used as supercritical fluids.

| Solvent | Molecular mass (g/mol) |

Critical temperature (K) |

Critical pressure (MPa (atm)) |

Critical density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 44.01 | 304.1 | 7.38 (72.8) | 0.469 |

| Water (H2O) | 18.015 | 647.096 | 22.064 (217.755) | 0.322 |

| Methane (CH4) | 16.04 | 190.4 | 4.60 (45.4) | 0.162 |

| Ethane (C2H6) | 30.07 | 305.3 | 4.87 (48.1) | 0.203 |

| Propane (C3H8) | 44.09 | 369.8 | 4.25 (41.9) | 0.217 |

| Ethylene (C2H4) | 28.05 | 282.4 | 5.04 (49.7) | 0.215 |

| Propylene (C3H6) | 42.08 | 364.9 | 4.60 (45.4) | 0.232 |

| Methanol (CH3OH) | 32.04 | 512.6 | 8.09 (79.8) | 0.272 |

| Ethanol (C2H5OH) | 46.07 | 513.9 | 6.14 (60.6) | 0.276 |

| Acetone (C3H6O) | 58.08 | 508.1 | 4.70 (46.4) | 0.278 |

| Nitrous oxide (N2O) | 44.013 | 306.57 | 7.35 (72.5) | 0.452 |

Table 2 shows density, diffusivity and viscosity for typical liquids, gases and supercritical fluids.

| Density (kg/m3) | Viscosity (μPa·s) | Diffusivity (mm2/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gases | 1 | 10 | 1–10 |

| Supercritical fluids | 100–1000 | 50–100 | 0.01–0.1 |

| Liquids | 1000 | 500–1000 | 0.001 |

Also, there is no surface tension in a supercritical fluid, as there is no liquid/gas phase boundary. By changing the pressure and temperature of the fluid, the properties can be "tuned" to be more liquid-like or more gas-like. One of the most important properties is the solubility of material in the fluid. Solubility in a supercritical fluid tends to increase with density of the fluid (at constant temperature). Since density increases with pressure, solubility tends to increase with pressure. The relationship with temperature is a little more complicated. At constant density, solubility will increase with temperature. However, close to the critical point, the density can drop sharply with a slight increase in temperature. Therefore, close to the critical temperature, solubility often drops with increasing temperature, then rises again.

Mixtures

Typically, supercritical fluids are completely miscible with each other, so that a binary mixture forms a single gaseous phase if the critical point of the mixture is exceeded. However, exceptions are known in systems where one component is much more volatile than the other, which in some cases form two immiscible gas phases at high pressure and temperatures above the component critical points. This behavior has been found in systems such as N2-NH3, NH3-CH4, SO2-N2 and n-butane-H2O.

The critical point of a binary mixture can be estimated as the arithmetic mean of the critical temperatures and pressures of the two components,

where χi denotes the mole fraction of component i.

For greater accuracy, the critical point can be calculated using equations of state, such as the Peng–Robinson, or group-contribution methods. Other properties, such as density, can also be calculated using equations of state.

Phase diagram

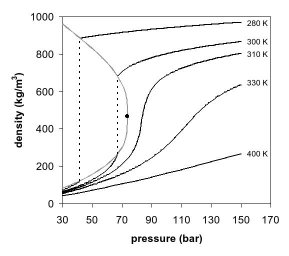

Figures 1 and 2 show two-dimensional projections of a phase diagram. In the pressure-temperature phase diagram (Fig. 1) the boiling curve separates the gas and liquid region and ends in the critical point, where the liquid and gas phases disappear to become a single supercritical phase.

The appearance of a single phase can also be observed in the density-pressure phase diagram for carbon dioxide (Fig. 2). At well below the critical temperature, e.g., 280 K, as the pressure increases, the gas compresses and eventually (at just over 40 bar) condenses into a much denser liquid, resulting in the discontinuity in the line (vertical dotted line). The system consists of 2 phases in equilibrium, a dense liquid and a low density gas. As the critical temperature is approached (300 K), the density of the gas at equilibrium becomes higher, and that of the liquid lower. At the critical point (304.1 K (31.0 °C; 87.7 °F) and 7.38 MPa (73.8 bar)), there is no difference in density, and the two phases become one fluid phase. Thus, above the critical temperature a gas cannot be liquefied by pressure. At slightly above the critical temperature (310 K), in the vicinity of the critical pressure, the line is almost vertical. A small increase in pressure causes a large increase in the density of the supercritical phase. Many other physical properties also show large gradients with pressure near the critical point, e.g. viscosity, the relative permittivity and the solvent strength, which are all closely related to the density. At higher temperatures, the fluid starts to behave more like an ideal gas, with a more linear density/pressure relationship, as can be seen in Figure 2. For carbon dioxide at 400 K, the density increases almost linearly with pressure.

Many pressurized gases are actually supercritical fluids. For example, nitrogen has a critical point of 126.2 K (−147.0 °C; −232.5 °F) and 3.4 MPa (34 bar). Therefore, nitrogen (or compressed air) in a gas cylinder above this pressure is actually a supercritical fluid. These are more often known as permanent gases. At room temperature, they are well above their critical temperature, and therefore behave as a nearly ideal gas, similar to CO2 at 400 K above. However, they cannot be liquified by mechanical pressure unless cooled below their critical temperature, requiring gravitational pressure such as within gas giants to produce a liquid or solid at high temperatures. Above the critical temperature, elevated pressures can increase the density enough that the SCF exhibits liquid-like density and behaviour. At very high pressures, an SCF can be compressed into a solid because the melting curve extends to the right of the critical point in the P/T phase diagram. While the pressure required to compress supercritical CO2 into a solid can be, depending on the temperature, as low as 570 MPa, that required to solidify supercritical water is 14,000 MPa.

The Fisher–Widom line, the Widom line, or the Frenkel line are thermodynamic concepts that allow to distinguish liquid-like and gas-like states within the supercritical fluid.

History

In 1822, Baron Charles Cagniard de la Tour discovered the critical point of a substance in his famous cannon barrel experiments. Listening to discontinuities in the sound of a rolling flint ball in a sealed cannon filled with fluids at various temperatures, he observed the critical temperature. Above this temperature, the densities of the liquid and gas phases become equal and the distinction between them disappears, resulting in a single supercritical fluid phase.

In recent years, a significant effort has been devoted to investigation of various properties of supercritical fluids. Supercritical fluids have found application in a variety of fields, ranging from the extraction of floral fragrance from flowers to applications in food science such as creating decaffeinated coffee, functional food ingredients, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, polymers, powders, bio- and functional materials, nano-systems, natural products, biotechnology, fossil and bio-fuels, microelectronics, energy and environment. Much of the excitement and interest of the past decade is due to the enormous progress made in increasing the power of relevant experimental tools. The development of new experimental methods and improvement of existing ones continues to play an important role in this field, with recent research focusing on dynamic properties of fluids.

Natural occurrence

Hydrothermal circulation

Hydrothermal circulation occurs within the Earth's crust wherever fluid becomes heated and begins to convect. These fluids are thought to reach supercritical conditions under a number of different settings, such as in the formation of porphyry copper deposits or high temperature circulation of seawater in the sea floor. At mid-ocean ridges, this circulation is most evident by the appearance of hydrothermal vents known as "black smokers". These are large (metres high) chimneys of sulfide and sulfate minerals which vent fluids up to 400 °C. The fluids appear like great black billowing clouds of smoke due to the precipitation of dissolved metals in the fluid. It is likely that at that depth many of these vent sites reach supercritical conditions, but most cool sufficiently by the time they reach the sea floor to be subcritical. One particular vent site, Turtle Pits, has displayed a brief period of supercriticality at the vent site. A further site, Beebe, in the Cayman Trough, is thought to display sustained supercriticality at the vent orifice.

Planetary atmospheres

The atmosphere of Venus is 96.5% carbon dioxide and 3.5% nitrogen. The surface pressure is 9.3 megapascals (1,350 psi) and the surface temperature is 735 K (462 °C; 863 °F), above the critical points of both major constituents and making the surface atmosphere a supercritical fluid.

The interior atmospheres of the Solar System's four giant planets are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium at temperatures well above their critical points. The gaseous outer atmospheres of the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn transition smoothly into the dense liquid interior, while the nature of the transition zones of the ice giants Neptune and Uranus is unknown. Theoretical models of extrasolar planet Gliese 876 d have posited an ocean of pressurized, supercritical fluid water with a sheet of solid high pressure water ice at the bottom.

Applications

Supercritical fluid extraction

The advantages of supercritical fluid extraction (compared with liquid extraction) are that it is relatively rapid because of the low viscosities and high diffusivities associated with supercritical fluids. Alternative solvents to supercritical fluids may be poisonous, flammable or an environmental hazard to a much larger extent than water or carbon dioxide are. The extraction can be selective to some extent by controlling the density of the medium, and the extracted material is easily recovered by simply depressurizing, allowing the supercritical fluid to return to gas phase and evaporate leaving little or no solvent residues. Carbon dioxide is the most common supercritical solvent. It is used on a large scale for the decaffeination of green coffee beans, the extraction of hops for beer production, and the production of essential oils and pharmaceutical products from plants. A few laboratory test methods include the use of supercritical fluid extraction as an extraction method instead of using traditional solvents.

Supercritical fluid decomposition

Supercritical water can be used to decompose biomass via supercritical water gasification of biomass. This type of biomass gasification can be used to produce hydrocarbon fuels for use in an efficient combustion device or to produce hydrogen for use in a fuel cell. In the latter case, hydrogen yield can be much higher than the hydrogen content of the biomass due to steam reforming where water is a hydrogen-providing participant in the overall reaction.

Dry-cleaning

Supercritical carbon dioxide (SCD) can be used instead of PERC (perchloroethylene) or other undesirable solvents for dry-cleaning. Supercritical carbon dioxide sometimes intercalates into buttons, and, when the SCD is depressurized, the buttons pop, or break apart. Detergents that are soluble in carbon dioxide improve the solvating power of the solvent. CO2-based dry cleaning equipment uses liquid CO2, not supercritical CO2, to avoid damage to the buttons.

Supercritical fluid chromatography

Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) can be used on an analytical scale, where it combines many of the advantages of high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography (GC). It can be used with non-volatile and thermally labile analytes (unlike GC) and can be used with the universal flame ionization detector (unlike HPLC), as well as producing narrower peaks due to rapid diffusion. In practice, the advantages offered by SFC have not been sufficient to displace the widely used HPLC and GC, except in a few cases such as chiral separations and analysis of high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons. For manufacturing, efficient preparative simulated moving bed units are available. The purity of the final products is very high, but the cost makes it suitable only for very high-value materials such as pharmaceuticals.

Chemical reactions

Changing the conditions of the reaction solvent can allow separation of phases for product removal, or single phase for reaction. Rapid diffusion accelerates diffusion controlled reactions. Temperature and pressure can tune the reaction down preferred pathways, e.g., to improve yield of a particular chiral isomer. There are also significant environmental benefits over conventional organic solvents. Industrial syntheses that are performed at supercritical conditions include those of polyethylene from supercritical ethene, isopropyl alcohol from supercritical propene, 2-butanol from supercritical butene, and ammonia from a supercritical mix of nitrogen and hydrogen. Other reactions were, in the past, performed industrially in supercritical conditions, including the synthesis of methanol and thermal (non-catalytic) oil cracking. Because of the development of effective catalysts, the required temperatures of those two processes have been reduced and are no longer supercritical.

Impregnation and dyeing

Impregnation is, in essence, the converse of extraction. A substance is dissolved in the supercritical fluid, the solution flowed past a solid substrate, and is deposited on or dissolves in the substrate. Dyeing, which is readily carried out on polymer fibres such as polyester using disperse (non-ionic) dyes, is a special case of this. Carbon dioxide also dissolves in many polymers, considerably swelling and plasticising them and further accelerating the diffusion process.

Nano and micro particle formation

The formation of small particles of a substance with a narrow size distribution is an important process in the pharmaceutical and other industries. Supercritical fluids provide a number of ways of achieving this by rapidly exceeding the saturation point of a solute by dilution, depressurization or a combination of these. These processes occur faster in supercritical fluids than in liquids, promoting nucleation or spinodal decomposition over crystal growth and yielding very small and regularly sized particles. Recent supercritical fluids have shown the capability to reduce particles up to a range of 5–2000 nm.

Generation of pharmaceutical cocrystals

Supercritical fluids act as a new medium for the generation of novel crystalline forms of APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) named as pharmaceutical cocrystals. Supercritical fluid technology offers a new platform that allows a single-step generation of particles that are difficult or even impossible to obtain by traditional techniques. The generation of pure and dried new cocrystals (crystalline molecular complexes comprising the API and one or more conformers in the crystal lattice) can be achieved due to unique properties of SCFs by using different supercritical fluid properties: supercritical CO2 solvent power, anti-solvent effect and its atomization enhancement.

Supercritical drying

Supercritical drying is a method of removing solvent without surface tension effects. As a liquid dries, the surface tension drags on small structures within a solid, causing distortion and shrinkage. Under supercritical conditions there is no surface tension, and the supercritical fluid can be removed without distortion. Supercritical drying is used in the manufacturing process of aerogels and drying of delicate materials such as archaeological samples and biological samples for electron microscopy.

Supercritical water electrolysis

Electrolysis of water in a supercritical state reduces the overpotentials found in other electrolysers, thereby improving the electrical efficiency of the production of oxygen and hydrogen.

Increased temperature reduces thermodynamic barriers and increases kinetics. No bubbles of oxygen or hydrogen are formed on the electrodes, therefore no insulating layer is formed between catalyst and water, reducing the ohmic losses. The gas-like properties provide rapid mass transfer.

Supercritical water oxidation

Supercritical water oxidation uses supercritical water as a medium in which to oxidize hazardous waste, eliminating production of toxic combustion products that burning can produce.

The waste product to be oxidised is dissolved in the supercritical water along with molecular oxygen (or an oxidising agent that gives up oxygen upon decomposition, e.g. hydrogen peroxide) at which point the oxidation reaction occurs.

Supercritical water hydrolysis

Supercritical hydrolysis is a method of converting all biomass polysaccharides as well the associated lignin into low molecular compounds by contacting with water alone under supercritical conditions. The supercritical water, acts as a solvent, a supplier of bond-breaking thermal energy, a heat transfer agent and as a source of hydrogen atoms. All polysaccharides are converted into simple sugars in near-quantitative yield in a second or less. The aliphatic inter-ring linkages of lignin are also readily cleaved into free radicals that are stabilized by hydrogen originating from the water. The aromatic rings of the lignin are unaffected under short reaction times so that the lignin-derived products are low molecular weight mixed phenols. To take advantage of the very short reaction times needed for cleavage a continuous reaction system must be devised. The amount of water heated to a supercritical state is thereby minimized.

Supercritical water gasification

Supercritical water gasification is a process of exploiting the beneficial effect of supercritical water to convert aqueous biomass streams into clean water and gases like H2, CH4, CO2, CO etc.

Supercritical desalination

The solubility of dissolved ions drops precipitously once a fluid becomes supercritical. This effect can be used to precipitate salts from high salinity desalination streams, with solubility of different salts decreasing rapidly as water approaches supercritical temperatures. Complex cycle design can enable selective precipitation and improved heat recovery. Some very saline water sources like produced water also have high hydrocarbon content, which can be oxidized by supercritical desalination.

Supercritical fluid in power generation

The efficiency of a heat engine is ultimately dependent on the temperature difference between heat source and sink (Carnot cycle). To improve efficiency of power stations the operating temperature must be raised. Using water as the working fluid, this takes it into supercritical conditions. Efficiencies can be raised from about 39% for subcritical operation to about 45% using current technology. Many coal-fired supercritical steam generators are operational all over the world. Supercritical carbon dioxide is also proposed as a working fluid, which would have the advantage of lower critical pressure than water, but issues with corrosion are not yet fully solved. One proposed application is the Allam cycle.

Supercritical water reactors (SCWRs) are proposed advanced nuclear systems that offer similar thermal efficiency gains.

Biodiesel production

Conversion of vegetable oil to biodiesel is via a transesterification reaction, where a triglyceride is converted to the methyl esters (of the fatty acids) plus glycerol. This is usually done using methanol and caustic or acid catalysts, but can be achieved using supercritical methanol without a catalyst. The method of using supercritical methanol for biodiesel production was first studied by Saka and his coworkers. This has the advantage of allowing a greater range and water content of feedstocks (in particular, used cooking oil), the product does not need to be washed to remove catalyst, and is easier to design as a continuous process.

Enhanced oil recovery and carbon capture and storage

Supercritical carbon dioxide is used to enhance oil recovery in mature oil fields. At the same time, there is the possibility of using "clean coal technology" to combine enhanced recovery methods with carbon sequestration. The CO2 is separated from other flue gases, compressed to the supercritical state, and injected into geological storage, possibly into existing oil fields to improve yields.

At present, only schemes isolating fossil CO2 from natural gas actually use carbon storage, (e.g., Sleipner gas field), but there are many plans for future CCS schemes involving pre- or post-combustion CO2. There is also the possibility to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere by using biomass to generate power and sequestering the CO2 produced.

Enhanced geothermal system

The use of supercritical carbon dioxide, instead of water, has been examined as a geothermal working fluid.

Refrigeration

Supercritical carbon dioxide is also emerging as a useful high-temperature refrigerant, being used in new, CFC/HFC-free domestic heat pumps making use of the transcritical cycle. These systems are undergoing continuous development with supercritical carbon dioxide heat pumps already being successfully marketed in Asia. The EcoCute systems from Japan are some of the first commercially successful high-temperature domestic water heat pumps.

Supercritical fluid deposition

Supercritical fluids can be used to deposit functional nanostructured films and nanometer-size particles of metals onto surfaces. The high diffusivities and concentrations of precursor in the fluid as compared to the vacuum systems used in chemical vapour deposition allow deposition to occur in a surface reaction rate limited regime, providing stable and uniform interfacial growth. This is crucial in developing more powerful electronic components, and metal particles deposited in this way are also powerful catalysts for chemical synthesis and electrochemical reactions. Additionally, due to the high rates of precursor transport in solution, it is possible to coat high surface area particles which under chemical vapour deposition would exhibit depletion near the outlet of the system and also be likely to result in unstable interfacial growth features such as dendrites. The result is very thin and uniform films deposited at rates much faster than atomic layer deposition, the best other tool for particle coating at this size scale.

Antimicrobial properties

CO2 at high pressures has antimicrobial properties. While its effectiveness has been shown for various applications, the mechanisms of inactivation have not been fully understood although they have been investigated for more than 60 years.