|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /priˈɡæbəlɪn/ |

| Trade names | Lyrica, others[2] |

| Synonyms | 3-Isobutyl GABA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605045 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability |

Physical: Moderate[1] Psychological: Moderate[1] |

| Addiction liability |

Low[1] |

| Routes of administration |

By mouth |

| Drug class | Gabapentinoid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High (≥90% rapidly absorbed; administration with food has no significant effect on bioavailability)[3] |

| Protein binding | <1 class="reference" id="cite_ref-pmid20818832_4-0" sup="">[4] |

Common side effects include: sleepiness, confusion, trouble with memory, poor motor coordination, dry mouth, problem with vision, and weight gain.[11] Potentially serious side effects include angioedema, drug misuse, and an increased suicide risk.[11] When pregabalin is taken at high doses over a long period of time, addiction may occur, but if taken at usual doses the risk of addiction is low.[1] Pregabalin is a gabapentinoid and acts by inhibiting certain calcium channels.[18][19]

Parke-Davis developed pregabalin as a successor to gabapentin and was brought to market by Pfizer after the company acquired Warner-Lambert.[20][21] There is to be no generic version available in the United States until 2018.[22] A generic version is available in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and Germany.[23][24][25] In the US it costs about 300–400 USD per month.[11] Pregabalin is a Schedule V controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (CSA).

Medical uses

Box of 150 mg Lyrica (pregabalin) capsules from Finland

Seizures

Pregabalin is useful when added to other treatments, when those other treatments are not controlling partial epilepsy.[26] Its use alone is less effective than some other seizure medications.[27] It is unclear how it compares to gabapentin for this use.[27]Neuropathic pain

The European Federation of Neurological Societies recommends pregabalin as a first line agent for the treatment of pain associated with diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and central neuropathic pain.[28] A minority obtain substantial benefit, and a larger number obtain moderate benefit.[29] Other first line agents, including gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants, are given equal weight as first line agents and, unlike pregabalin, are available as less expensive generics.[30]Pregabalin is not recommended for certain other types of neuropathic pain such as trigeminal neuralgia[31] and its use in cancer-associated neuropathic pain is controversial.[31] There is no evidence for its use in the prevention of migraines and gabapentin has been found not to be useful.[32] It has been examined for the prevention of post-surgical chronic pain, but its utility for this purpose is controversial.[33][34]

Pregabalin is generally not regarded as efficacious in the treatment of acute pain.[29] In trials examining the utility of pregabalin for the treatment of acute post-surgical pain, no effect on overall pain levels was observed, but people did require less morphine and had fewer opioid-related side effects.[33][35] Several possible mechanisms for pain improvement have been discussed.[12]

Anxiety disorders

The World Federation of Biological Psychiatry recommends pregabalin as one of several first line agents for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, but recommends other agents such as SSRIs as first line treatment for obsessive–compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.[36] It appears to have anxiolytic effects similar to benzodiazepines with less risk of dependence.[37][38]The effects of pregabalin appear after 1 week of use and is similar in effectiveness to lorazepam, alprazolam, and venlafaxine, but pregabalin has demonstrated superiority by producing more consistent therapeutic effects for psychosomatic anxiety symptoms.[39] Long-term trials have shown continued effectiveness without the development of tolerance, and, in addition, unlike benzodiazepines, it has a beneficial effect on sleep and sleep architecture, characterized by the enhancement of slow-wave sleep.[39] It produces less severe cognitive and psychomotor impairment compared to those drugs; it also has a low potential for abuse and dependence and may be preferred over the benzodiazepines for these reasons.[39][40]

Other uses

Evidence finds little benefit and significant risk in those with chronic low back pain.[41]Side effects

Pregabalin has been shown to produce therapeutic effects that are similar to other controlled substances. In a study with recreational users of sedative and hypnotic drugs, a 450 mg dose of pregabalin resulted in subjective ratings of a "good drug effect" and "high" and "liking" similar to 30 mg of diazepam. In clinical studies, pregabalin showed a side effect profile similar to other central nervous system depressants.[42]Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of pregabalin include:[43][44]

- Very common (>10% of patients): dizziness, drowsiness.

- Common (1–10% of patients): blurred vision, diplopia, increased appetite and subsequent weight gain, euphoria, confusion, vivid dreams, changes in libido (increase or decrease), irritability, ataxia, attention changes, feeling high, abnormal coordination, memory impairment, tremors, dysarthria, parasthesia, vertigo, dry mouth and constipation, vomiting and flatulence, erectile dysfunction, fatigue, peripheral edema, feeling the effects of drunkenness, abnormal walking, asthenia, nasopharyngitis, increased creatine kinase level.

- Infrequent (0.1–1% of patients): depression, lethargy, agitation, anorgasmia, hallucinations, myoclonus, hypoaesthesia, hyperaesthesia, tachycardia, excessive salivation, hypoglycaemia, sweating, flushing, rash, muscle cramp, myalgia, arthralgia, urinary incontinence, dysuria, thrombocytopenia, kidney calculus

- Rare (<0 .1="" a="" href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutropenia" of="" patients="" title="Neutropenia">neutropenia

Withdrawal symptoms

Following abrupt or rapid discontinuation of pregabalin, some people reported symptoms suggestive of physical dependence. The FDA determined that the substance dependence profile of pregabalin, as measured by a patient physical withdrawal checklist, was quantitatively less than benzodiazepines.[42] Even people who have discontinued short term and or long term use of pregabalin have experienced withdrawal symptoms, including insomnia, headache, nausea, anxiety, diarrhea, flu like symptoms, nervousness, major depression, pain, convulsions, hyperhidrosis and dizziness.[46]Pregnancy

It is unclear if it is safe for use in pregnancy with some studies showing potential harm.[47]Overdose

Several renal failure patients developed myoclonus while receiving pregabalin, apparently as a result of gradual accumulation of the drug. Acute overdosage may be manifested by somnolence, tachycardia and hypertonicity. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of pregabalin may be measured to monitor therapy or to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients.[48][49][50]Interactions

No interactions have been demonstrated in vivo. The manufacturer notes some potential pharmacological interactions with opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, ethanol (alcohol), and other drugs that depress the central nervous system. ACE inhibitors may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of pregabalin. Pregabalin may enhance the fluid-retaining effect of anti-diabetic agents (Thiazolidinedione).[51]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Pregabalin is not a GABAA or GABAB receptor agonist.

Pregabalin is a gabapentinoid, or a ligand of the auxiliary α2δ subunit site of certain voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs), and thereby acts as an inhibitor of α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs.[52][18] There are two drug-binding α2δ subunits, α2δ-1 and α2δ-2, and pregabalin shows similar affinity for (and hence lack of selectivity between) these two sites.[18] Pregabalin is selective in its binding to the α2δ VDCC subunit.[52][53] Despite the fact that pregabalin is a GABA analogue,[54] it does not bind to the GABA receptors, does not convert into GABA or a GABA receptor agonist in vivo, and does not directly modulate GABA transport or metabolism.[52][19] However, pregabalin has been found to produce a dose-dependent increase in the brain expression of L-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the enzyme responsible for synthesizing GABA, and hence may have some indirect GABAergic effects by increasing GABA levels in the brain.[55][55][56][57] There is currently no evidence that the effects of pregabalin are mediated by any mechanism other than inhibition of α2δ-containing VDCCs.[58][52] In accordance, inhibition of α2δ-1-containing VDCCs by pregabalin appears to be responsible for its anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects.[52][58]

The endogenous α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, which closely resemble pregabalin and the other gabapentinoids in chemical structure, are apparent ligands of the α2δ VDCC subunit with similar affinity as the gabapentinoids (e.g., IC50 = 71 nM for L-isoleucine), and are present in human cerebrospinal fluid at micromolar concentrations (e.g., 12.9 µM for L-leucine, 4.8 µM for L-isoleucine).[59] It has been theorized that they may be the endogenous ligands of the subunit and that they may competitively antagonize the effects of gabapentinoids.[59][60] In accordance, while gabapentinoids like pregabalin and gabapentin have nanomolar affinities for the α2δ subunit, their potencies in vivo are in the low micromolar range, and competition for binding by endogenous L-amino acids has been said to likely be responsible for this discrepancy.[58]

Pregabalin was found to possess 6-fold higher affinity than gabapentin for α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs in one study.[17][61] However, another study found that pregabalin and gabapentin had similar affinities for the human recombinant α2δ-1 subunit (Ki = 32 nM and 40 nM, respectively).[62] In any case, pregabalin is 2 to 4 times as potent as an analgesic than gabapentin[54][63] and, in animals, appears to be 3 to 10 times as potent as gabapentin as an anticonvulsant.[54][63]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Pregabalin is absorbed from the intestines by an active transport process mediated via the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1, SLC7A5), a transporter for amino acids such as L-leucine and L-phenylalanine.[18][52][64] Very few (less than 10 drugs) are known to be transported by this transporter.[65] Unlike gabapentin, which is transported solely by the LAT1,[64][4] pregabalin seems to be transported not only by the LAT1 but also by other carriers.[18] The LAT1 is easily saturable, so the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin are dose-dependent, with diminished bioavailability and delayed peak levels at higher doses.[18] In contrast, this is not the case for pregabalin, which shows linear pharmacokinetics and no saturation of absorption.[18]The oral bioavailability of pregabalin is greater than or equal to 90% across and beyond its entire clinical dose range (75 to 900 mg/day).[4] Food does not significantly influence the oral bioavailability of pregabalin.[4] Pregabalin is rapidly absorbed when administered on an empty stomach, with a Tmax (time to peak levels) of generally less than or equal to 1 hour at doses of 300 mg or less.[18][3] However, food has been found to substantially delay the absorption of pregabalin and to significantly reduce peak levels without affecting the bioavailability of the drug; Tmax values for pregabalin of 0.6 hours in a fasted state and 3.2 hours in a fed state (5-fold difference), and the Cmax is reduced by 25–31% in a fed versus fasted state.[4]

Distribution

Pregabalin crosses the blood–brain barrier and enters the central nervous system.[52] However, due to its low lipophilicity,[4] pregabalin requires active transport across the blood–brain barrier. The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier[68] and transports pregabalin across into the brain.[64][52][66][67] Pregabalin has been shown to cross the placenta in rats and is present in the milk of lactating rats.[3] In humans, the volume of distribution of an orally administered dose of pregabalin is approximately 0.56 L/kg.[3] Pregabalin is not significantly bound to plasma proteins (<1 class="reference" id="cite_ref-pmid20818832_4-6" sup="">[4]Metabolism

Pregabalin undergoes little or no metabolism.[18][4][69] In experiments using nuclear medicine techniques, it was revealed that approximately 98% of the radioactivity recovered in the urine was unchanged pregabalin.[3] The major metabolite is N-methylpregabalin.[3]Elimination

Pregabalin is eliminated renally in the urine, mainly in its unchanged form.[4][3] It has a relatively short elimination half-life, with a reported value 6.3 hours.[4] Because of its short elimination half-life, pregabalin is administered 2 to 3 times per day to maintain therapeutic levels.[4] The renal clearance of pregabalin is 73 mL/minute.[70]Chemistry

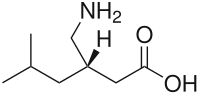

Chemical structures of GABA, pregabalin and two other gabapentinoids, gabapentin and phenibut.

Pregabalin is a 3-substituted derivative of GABA; hence, it is a GABA analogue, as well as a γ-amino acid.[71][53] Specifically, pregabalin is (S)-(+)-3-isobutyl-GABA.[72][73][74] Pregabalin also closely resembles the α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, and this may be of greater relevance in relation to its pharmacodynamics than its structural similarity to GABA.[59][60][72]

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of pregabalin have been described.[75][76]History

Pregabalin was synthesized in 1990 as an anticonvulsant. It was invented by medicinal chemist Richard Bruce Silverman at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.[77] Silverman is best known for identifying the drug pregabalin as a possible treatment for epileptic seizures.[78] During 1988 to 1990, Ryszard Andruszkiewicz, a visiting research fellow, synthesized a series of molecules for Silverman.[79] One looked particularly promising.[80] The molecule was effectively shaped for transportation into the brain, where it activated L-glutamic acid decarboxylase, an enzyme. Silverman hoped that the enzyme would increase production of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA and block convulsions.[78] Eventually, the set of molecules were sent to Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals for testing. The drug was approved in the European Union in 2004. The US received FDA approval for use in treating epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, and postherpetic neuralgia in December 2004. Pregabalin then appeared on the US market under the brand name Lyrica in fall of 2005.[81]Society and culture

Cost

In the United States as of april 2018 the cost is between 6.29 and 8.39 USD per 150 mg capsule.[82]Legal status

- United States: During clinical trials a small number of users (~4%) reported euphoria after use, which led to its control in the US.[83] The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classified pregabalin as a depressant and placed pregabalin, including its salts, and all products containing pregabalin into Schedule V of the Controlled Substances Act.

- Norway: Pregabalin is in prescription Schedule B, alongside benzodiazepines.

- United Kingdom: On January 14, 2016 the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) wrote a letter to Home Office ministers recommending that both drugs be reclassified as a Class C drug and scheduled under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001 (as amended) as Schedule 3. The letter warns there is a risk of addiction for both drugs, as well as misuse and diversion.[89][90][91] Recreational users of pregabalin in Belfast, Northern Ireland call the drug "Budweisers" because it induces a state similar to drunkenness.[89]

Approval

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved pregabalin for adjunctive therapy for adults with partial onset seizures, management of postherpetic neuralgia and neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury and diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and the treatment of fibromyalgia.[92] Pregabalin has also been approved in the European Union and Russia (but not in US) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.[39][93]Marketing

Since 2008, Pfizer has engaged in extensive direct-to-consumer advertising campaigns to promote its branded product Lyrica for fibromyalgia and diabetic nerve pain indications. In January 2016, the company spent a record amount, $24.6 million for a single drug on TV ads, reaching global revenues of $14 billion, more than half in the United States.[94]Up until 2009, Pfizer promoted Lyrica for other uses which had not been approved by medical regulators. For Lyrica and three other drugs, Pfizer was fined a record amount of US$2.3 billion by the Department of Justice,[95][96][97] after pleading guilty to advertising and branding "with the intent to defraud or mislead." Pfizer illegally promoted the drugs, with doctors "invited to consultant meetings, many in resort locations; Attendees expenses were paid; they received a fee just for being there", according to prosecutor Michael Loucks.[95][96]