In mathematics and physics, scattering theory is a framework for studying and understanding the scattering of waves and particles. Wave scattering corresponds to the collision and scattering of a wave with some material object, for instance sunlight scattered by rain drops to form a rainbow. Scattering also includes the interaction of billiard balls on a table, the Rutherford scattering (or angle change) of alpha particles by gold nuclei, the Bragg scattering (or diffraction) of electrons and X-rays by a cluster of atoms, and the inelastic scattering of a fission fragment as it traverses a thin foil. More precisely, scattering consists of the study of how solutions of partial differential equations, propagating freely "in the distant past", come together and interact with one another or with a boundary condition, and then propagate away "to the distant future". The direct scattering problem is the problem of determining the distribution of scattered radiation/particle flux basing on the characteristics of the scatterer. The inverse scattering problem is the problem of determining the characteristics of an object (e.g., its shape, internal constitution) from measurement data of radiation or particles scattered from the object.

Since its early statement for radiolocation, the problem has found vast number of applications, such as echolocation, geophysical survey, nondestructive testing, medical imaging and quantum field theory, to name just a few.

Conceptual underpinnings

The concepts used in scattering theory go by different names in different fields. The object of this section is to point the reader to common threads.

Composite targets and range equations

When the target is a set of many scattering centers whose relative position varies unpredictably, it is customary to think of a range equation whose arguments take different forms in different application areas. In the simplest case consider an interaction that removes particles from the "unscattered beam" at a uniform rate that is proportional to the incident flux of particles per unit area per unit time, i.e. that

where Q is an interaction coefficient and x is the distance traveled in the target.

The above ordinary first-order differential equation has solutions of the form:

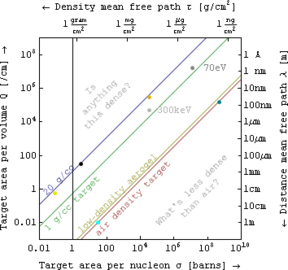

where Io is the initial flux, path length Δx ≡ x − xo, the second equality defines an interaction mean free path λ, the third uses the number of targets per unit volume η to define an area cross-section σ, and the last uses the target mass density ρ to define a density mean free path τ. Hence one converts between these quantities via Q = 1/λ = ησ = ρ/τ, as shown in the figure at left.

In electromagnetic absorption spectroscopy, for example, interaction coefficient (e.g. Q in cm−1) is variously called opacity, absorption coefficient, and attenuation coefficient. In nuclear physics, area cross-sections (e.g. σ in barns or units of 10−24 cm2), density mean free path (e.g. τ in grams/cm2), and its reciprocal the mass attenuation coefficient (e.g. in cm2/gram) or area per nucleon are all popular, while in electron microscopy the inelastic mean free path[1] (e.g. λ in nanometers) is often discussed[2] instead.

In theoretical physics

In mathematical physics, scattering theory is a framework for studying and understanding the interaction or scattering of solutions to partial differential equations. In acoustics, the differential equation is the wave equation, and scattering studies how its solutions, the sound waves, scatter from solid objects or propagate through non-uniform media (such as sound waves, in sea water, coming from a submarine). In the case of classical electrodynamics, the differential equation is again the wave equation, and the scattering of light or radio waves is studied. In particle physics, the equations are those of Quantum electrodynamics, Quantum chromodynamics and the Standard Model, the solutions of which correspond to fundamental particles.

In regular quantum mechanics, which includes quantum chemistry, the relevant equation is the Schrödinger equation, although equivalent formulations, such as the Lippmann-Schwinger equation and the Faddeev equations, are also largely used. The solutions of interest describe the long-term motion of free atoms, molecules, photons, electrons, and protons. The scenario is that several particles come together from an infinite distance away. These reagents then collide, optionally reacting, getting destroyed or creating new particles. The products and unused reagents then fly away to infinity again.

(The atoms and molecules are effectively particles for our purposes. Also, under everyday circumstances, only photons are being created and destroyed.) The solutions reveal which directions the products are most likely to fly off to and how quickly. They also reveal the probability of various reactions, creations, and decays occurring. There are two predominant techniques of finding solutions to scattering problems: partial wave analysis, and the Born approximation.

Elastic and inelastic scattering

The term "elastic scattering" implies that the internal states of the scattered particles do not change, and hence they emerge unchanged from the scattering process. In inelastic scattering, by contrast, the particles' internal state is changed, which may amount to exciting some of the electrons of a scattering atom, or the complete annihilation of a scattering particle and the creation of entirely new particles.

The example of scattering in quantum chemistry is particularly instructive, as the theory is reasonably complex while still having a good foundation on which to build an intuitive understanding. When two atoms are scattered off one another, one can understand them as being the bound state solutions of some differential equation. Thus, for example, the hydrogen atom corresponds to a solution to the Schrödinger equation with a negative inverse-power (i.e., attractive Coulombic) central potential. The scattering of two hydrogen atoms will disturb the state of each atom, resulting in one or both becoming excited, or even ionized, representing an inelastic scattering process.

The term "deep inelastic scattering" refers to a special kind of scattering experiment in particle physics.

The mathematical framework

In mathematics, scattering theory deals with a more abstract formulation of the same set of concepts. For example, if a differential equation is known to have some simple, localized solutions, and the solutions are a function of a single parameter, that parameter can take the conceptual role of time. One then asks what might happen if two such solutions are set up far away from each other, in the "distant past", and are made to move towards each other, interact (under the constraint of the differential equation) and then move apart in the "future". The scattering matrix then pairs solutions in the "distant past" to those in the "distant future".

Solutions to differential equations are often posed on manifolds. Frequently, the means to the solution requires the study of the spectrum of an operator on the manifold. As a result, the solutions often have a spectrum that can be identified with a Hilbert space, and scattering is described by a certain map, the S matrix, on Hilbert spaces. Spaces with a discrete spectrum correspond to bound states in quantum mechanics, while a continuous spectrum is associated with scattering states. The study of inelastic scattering then asks how discrete and continuous spectra are mixed together.

An important, notable development is the inverse scattering transform, central to the solution of many exactly solvable models.