| Hypercholesterolemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypercholesterolaemia, high cholesterol |

| |

| Xanthelasma palpebrarum, yellowish patches consisting of cholesterol deposits above the eyelids. These are more common in people with familial hypercholesterolemia. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

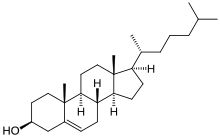

Hypercholesterolemia, also called high cholesterol, is the presence of high levels of cholesterol in the blood. It is a form of hyperlipidemia (high levels of lipids in the blood), hyperlipoproteinemia (high levels of lipoproteins in the blood), and dyslipidemia (any abnormalities of lipid and lipoprotein levels in the blood).

Elevated levels of non-HDL cholesterol and LDL in the blood may be a consequence of diet, obesity, inherited (genetic) diseases (such as LDL receptor mutations in familial hypercholesterolemia), or the presence of other diseases such as type 2 diabetes and an underactive thyroid.

Cholesterol is one of three major classes of lipids which all animal cells use to construct their membranes and is thus manufactured by all animal cells. Plant cells do manufacture phytosterols (similar to cholesterol), but in rather small quantities. It is also the precursor of the steroid hormones and bile acids. Since cholesterol is insoluble in water, it is transported in the blood plasma within protein particles (lipoproteins). Lipoproteins are classified by their density: very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL) and high density lipoprotein (HDL). All the lipoproteins carry cholesterol, but elevated levels of the lipoproteins other than HDL (termed non-HDL cholesterol), particularly LDL-cholesterol, are associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. In contrast, higher levels of HDL cholesterol are protective.

Avoiding trans fats and replacing saturated fats in adult diets with polyunsaturated fats are recommended dietary measures to reduce total blood cholesterol and LDL in adults. In people with very high cholesterol (e.g., familial hypercholesterolemia), diet is often not sufficient to achieve the desired lowering of LDL, and lipid-lowering medications are usually required. If necessary, other treatments such as LDL apheresis or even surgery (for particularly severe subtypes of familial hypercholesterolemia) are performed. About 34 million adults in the United States have high blood cholesterol.

Signs and symptoms

Although hypercholesterolemia itself is asymptomatic, longstanding elevation of serum cholesterol can lead to atherosclerosis (hardening of arteries). Over a period of decades, elevated serum cholesterol contributes to formation of atheromatous plaques in the arteries. This can lead to progressive narrowing of the involved arteries. Alternatively smaller plaques may rupture and cause a clot to form and obstruct blood flow. A sudden blockage of a coronary artery may result in a heart attack. A blockage of an artery supplying the brain can cause a stroke. If the development of the stenosis or occlusion is gradual, blood supply to the tissues and organs slowly diminishes until organ function becomes impaired. At this point tissue ischemia (restriction in blood supply) may manifest as specific symptoms. For example, temporary ischemia of the brain (commonly referred to as a transient ischemic attack) may manifest as temporary loss of vision, dizziness and impairment of balance, difficulty speaking, weakness or numbness or tingling, usually on one side of the body. Insufficient blood supply to the heart may cause chest pain, and ischemia of the eye may manifest as transient visual loss in one eye. Insufficient blood supply to the legs may manifest as calf pain when walking, while in the intestines it may present as abdominal pain after eating a meal.

Some types of hypercholesterolemia lead to specific physical findings. For example, familial hypercholesterolemia (Type IIa hyperlipoproteinemia) may be associated with xanthelasma palpebrarum (yellowish patches underneath the skin around the eyelids), arcus senilis (white or gray discoloration of the peripheral cornea), and xanthomata (deposition of yellowish cholesterol-rich material) of the tendons, especially of the fingers. Type III hyperlipidemia may be associated with xanthomata of the palms, knees and elbows.

Causes

Hypercholesterolemia is typically due to a combination of environmental and genetic factors. Environmental factors include weight, diet, and stress. Loneliness is also a risk factor.

Medical conditions and treatments

A number of other conditions can also increase cholesterol levels including diabetes mellitus type 2, obesity, alcohol use, monoclonal gammopathy, dialysis therapy, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome and anorexia nervosa. Several medications and classes of medications may interfere with lipid metabolism: thiazide diuretics, ciclosporin, glucocorticoids, beta blockers, retinoic acid, antipsychotics), certain anticonvulsants and medications for HIV as well as interferons.

Genetics

Genetic contributions are usually due to the additive effects of multiple genes ("polygenic"), though occasionally may be due to a single gene defect such as in the case of familial hypercholesterolaemia. In familial hypercholesterolemia, mutations may be present in the APOB gene (autosomal dominant), the autosomal recessive LDLRAP1 gene, autosomal dominant familial hypercholesterolemia (HCHOLA3) variant of the PCSK9 gene, or the LDL receptor gene. Familial hypercholesterolemia affects about one in 250 individuals.

Diet

Diet has an effect on blood cholesterol, but the size of this effect varies between individuals. Moreover, when dietary cholesterol intake goes down, production (principally by the liver) typically increases, so that blood cholesterol changes can be modest or even elevated. This compensatory response may explain hypercholesterolemia in anorexia nervosa. A 2016 review found tentative evidence that dietary cholesterol is associated with higher blood cholesterol. Trans fats have been shown to reduce levels of HDL while increasing levels of LDL. LDL and total cholesterol also increases by very high fructose intake.

As of 2018 there appears to be a modest positive, dose-related relationship between cholesterol intake and LDL cholesterol.

Diagnosis

| Interpretation of cholesterol levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cholesterol type | mmol/L | mg/dL | interpretation |

| total cholesterol | <5.2 | <200 | desirable |

| 5.2–6.2 | 200–239 | borderline | |

| >6.2 | >240 | high | |

| LDL cholesterol | <2.6 | <100 | most desirable |

| 2.6–3.3 | 100–129 | good | |

| 3.4–4.1 | 130–159 | borderline high | |

| 4.1–4.9 | 160–189 | high and undesirable | |

| >4.9 | >190 | very high | |

| HDL cholesterol | <1.0 | <40 | undesirable; risk increased |

| 1.0–1.5 | 41–59 | okay, but not optimal | |

| >1.55 | >60 | good; risk lowered | |

Cholesterol is measured in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) of blood in the United States and some other countries. In the United Kingdom, most European countries and Canada, millimoles per liter of blood (mmol/Ll) is the measure.

For healthy adults, the UK National Health Service recommends upper limits of total cholesterol of 5 mmol/L, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) of 3 mmol/L. For people at high risk of cardiovascular disease, the recommended limit for total cholesterol is 4 mmol/L, and 2 mmol/L for LDL.

In the United States, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute within the National Institutes of Health classifies total cholesterol of less than 200 mg/dL as “desirable,” 200 to 239 mg/dL as “borderline high,” and 240 mg/dL or more as “high”.

No absolute cutoff between normal and abnormal cholesterol levels exists, and interpretation of values must be made in relation to other health conditions and risk factors.

Higher levels of total cholesterol increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, particularly coronary heart disease. Levels of LDL or non-HDL cholesterol both predict future coronary heart disease; which is the better predictor is disputed. High levels of small dense LDL may be particularly adverse, although measurement of small dense LDL is not advocated for risk prediction. In the past, LDL and VLDL levels were rarely measured directly due to cost. Levels of fasting triglycerides were taken as an indicator of VLDL levels (generally about 45% of fasting triglycerides is composed of VLDL), while LDL was usually estimated by the Friedewald formula:

LDL total cholesterol – HDL – (0.2 x fasting triglycerides).

However, this equation is not valid on nonfasting blood samples or if fasting triglycerides are elevated >4.5 mmol/L (> ∼400 mg/dL). Recent guidelines have, therefore, advocated the use of direct methods for measurement of LDL wherever possible. It may be useful to measure all lipoprotein subfractions ( VLDL, IDL, LDL, and HDL) when assessing hypercholesterolemia and measurement of apolipoproteins and lipoprotein (a) can also be of value. Genetic screening is now advised if a form of familial hypercholesterolemia is suspected.

Classification

Classically, hypercholesterolemia was categorized by lipoprotein electrophoresis and the Fredrickson classification. Newer methods, such as "lipoprotein subclass analysis", have offered significant improvements in understanding the connection with atherosclerosis progression and clinical consequences. If the hypercholesterolemia is hereditary (familial hypercholesterolemia), more often a family history of premature, earlier onset atherosclerosis is found.

Screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2008 strongly recommends routine screening for men 35 years and older and women 45 years and older for lipid disorders and the treatment of abnormal lipids in people who are at increased risk of coronary heart disease. They also recommend routinely screening men aged 20 to 35 years and women aged 20 to 45 years if they have other risk factors for coronary heart disease. In 2016 they concluded that testing the general population under the age of 40 without symptoms is of unclear benefit.

In Canada, screening is recommended for men 40 and older and women 50 and older. In those with normal cholesterol levels, screening is recommended once every five years. Once people are on a statin further testing provides little benefit except to possibly determine compliance with treatment.

Treatment

Treatment recommendations have been based on four risk levels for heart disease. For each risk level, LDL cholesterol levels representing goals and thresholds for treatment and other action are made. The higher the risk category, the lower the cholesterol thresholds.

| Risk category | Criteria for risk category | Consider lifestyle modifications | Consider medication | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of risk factors† |

|

10-year risk of myocardial ischemia |

mmol/litre | mg/dL | mmol/litre | mg/dL | |

| High | Prior heart disease | OR | >20% | >2.6 | >100 | >2.6 | >100 |

| Moderately high | 2 or more | AND | 10–20% | >3.4 | >130 | >3.4 | >130 |

| Moderate | 2 or more | AND | <10% | >3.4 | >130 | >4.1 | >160 |

| Low | 0 or 1 | >4.1 | >160 | >4.9 | >190 | ||

| †Risk factors include cigarette smoking, hypertension (BP ≥140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medication), low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL), family history of premature heart disease, and age (men ≥45 years; women ≥55 years). | |||||||

For those at high risk, a combination of lifestyle modification and statins has been shown to decrease mortality.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle changes recommended for those with high cholesterol include: smoking cessation, limiting alcohol consumption, increasing physical activity, and maintaining a healthy weight.

Overweight or obese individuals can lower blood cholesterol by losing weight – on average a kilogram of weight loss can reduce LDL cholesterol by 0.8 mg/dl.

Diet

Eating a diet with a high proportion of vegetables, fruit, dietary fibre, and low in fats results in a modest decrease in total cholesterol.

Eating dietary cholesterol causes a small but significant rise in serum cholesterol, the magnitude of which can be predicted using the Keys and Hegsted equations. Dietary limits for cholesterol were proposed in United States, but not in Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia. Consequently, in 2015 the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee in the United States removed its recommendation of limiting cholesterol intake.

A 2020 Cochrane review found replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat resulted in a small decrease in cardiovascular disease by decreasing blood cholesterol. Other reviews have not found an effect from saturated fats on cardiovascular disease. Trans fats are recognized as a potential risk factor for cholesterol-related cardiovascular disease, and avoiding them in an adult diet is recommended.

The National Lipid Association recommends that people with familial hypercholesterolemia restrict intakes of total fat to 25–35% of energy intake, saturated fat to less than 7% of energy intake, and cholesterol to less than 200 mg per day. Changes in total fat intake in low calorie diets do not appear to affect blood cholesterol.

Increasing soluble fiber consumption has been shown to reduce levels of LDL cholesterol, with each additional gram of soluble fiber reducing LDL by an average of 2.2 mg/dL (0.057 mmol/L). Increasing consumption of whole grains also reduces LDL cholesterol, with whole grain oats being particularly effective. Inclusion of 2 g per day of phytosterols and phytostanols and 10 to 20 g per day of soluble fiber decreases dietary cholesterol absorption. A diet high in fructose can raise LDL cholesterol levels in the blood.

Medication

Statins are the typically used medications, in addition to healthy lifestyle interventions. Statins can reduce total cholesterol by about 50% in the majority of people, and are effective in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease in both people with and without pre-existing cardiovascular disease. In people without cardiovascular disease, statins have been shown to reduce all-cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal coronary heart disease, and strokes. Greater benefit is observed with the use of high-intensity statin therapy. Statins may improve quality of life when used in people without existing cardiovascular disease (i.e. for primary prevention). Statins decrease cholesterol in children with hypercholesterolemia, but no studies as of 2010 show improved outcomes and diet is the mainstay of therapy in childhood.

Other agents that may be used include fibrates, nicotinic acid, and cholestyramine. These, however, are only recommended if statins are not tolerated or in pregnant women. Injectable antibodies against the protein PCSK9 (evolocumab, bococizumab, alirocumab) can reduce LDL cholesterol and have been shown to reduce mortality.

Guidelines

In the USA, guidelines exist from the National Cholesterol Education Program (2004) and a joint body of professional societies led by the American Heart Association.

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has made recommendations for the treatment of elevated cholesterol levels, published in 2008, and a new guideline appeared in 2014 that covers the prevention of cardiovascular disease in general.

The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society published guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias in 2011.

Specific populations

Among people whose life expectancy is relatively short, hypercholesterolemia is not a risk factor for death by any cause including coronary heart disease. Among people older than 70, hypercholesterolemia is not a risk factor for being hospitalized with myocardial infarction or angina. There are also increased risks in people older than 85 in the use of statin drugs. Because of this, medications which lower lipid levels should not be routinely used among people with limited life expectancy.

The American College of Physicians recommends for hypercholesterolemia in people with diabetes:

- Lipid-lowering therapy should be used for secondary prevention of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity for all adults with known coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes.

- Statins should be used for primary prevention against macrovascular complications in adults with type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors.

- Once lipid-lowering therapy is initiated, people with type 2 diabetes mellitus should be taking at least moderate doses of a statin.

- For those people with type 2 diabetes who are taking statins, routine monitoring of liver function tests or muscle enzymes is not recommended except in specific circumstances.

Alternative medicine

According to a survey in 2002, alternative medicine was used in an attempt to treat cholesterol by 1.1% of U.S. adults. Consistent with previous surveys, this one found the majority of individuals (55%) used it in conjunction with conventional medicine. A systematic review of the effectiveness of herbal medicines utilized in traditional chinese medicine had inconclusive results due to the poor methodological quality of the included studies. A review of trials of phytosterols and/or phytostanols, average dose 2.15 g/day, reported an average of 9% lowering of LDL-cholesterol. In 2000, the Food and Drug Administration approved the labeling of foods containing specified amounts of phytosterol esters or phytostanol esters as cholesterol-lowering; in 2003, an FDA Interim Health Claim Rule extended that label claim to foods or dietary supplements delivering more than 0.8 g/day of phytosterols or phytostanols. Some researchers, however, are concerned about diet supplementation with plant sterol esters and draw attention to lack of long-term safety data.

Epidemiology

Rates of high total cholesterol in the United States in 2010 are just over 13%, down from 17% in 2000.

Average total cholesterol in the United Kingdom is 5.9 mmol/L, while in rural China and Japan, average total cholesterol is 4 mmol/L. Rates of coronary artery disease are high in Great Britain, but low in rural China and Japan.

Research directions

Gene therapy is being studied as a potential treatment.