The Game of Life, also known simply as Life, is a cellular automaton devised by the British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. It is a zero-player game, meaning that its evolution is determined by its initial state, requiring no further input. One interacts with the Game of Life by creating an initial configuration and observing how it evolves. It is Turing complete and can simulate a universal constructor or any other Turing machine.

Rules

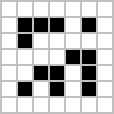

The universe of the Game of Life is an infinite, two-dimensional orthogonal grid of square cells, each of which is in one of two possible states, live or dead (or populated and unpopulated, respectively). Every cell interacts with its eight neighbours, which are the cells that are horizontally, vertically, or diagonally adjacent. At each step in time, the following transitions occur:

- Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbours dies, as if by underpopulation.

- Any live cell with two or three live neighbours lives on to the next generation.

- Any live cell with more than three live neighbours dies, as if by overpopulation.

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes a live cell, as if by reproduction.

These rules, which compare the behavior of the automaton to real life, can be condensed into the following:

- Any live cell with two or three live neighbours survives.

- Any dead cell with three live neighbours becomes a live cell.

- All other live cells die in the next generation. Similarly, all other dead cells stay dead.

The initial pattern constitutes the seed of the system. The first generation is created by applying the above rules simultaneously to every cell in the seed, live or dead; births and deaths occur simultaneously, and the discrete moment at which this happens is sometimes called a tick. Each generation is a pure function of the preceding one. The rules continue to be applied repeatedly to create further generations.

Origins

Stanislaw Ulam, while working at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in the 1940s, studied the growth of crystals, using a simple lattice network as his model. At the same time, John von Neumann, Ulam's colleague at Los Alamos, was working on the problem of self-replicating systems. Von Neumann's initial design was founded upon the notion of one robot building another robot. This design is known as the kinematic model. As he developed this design, von Neumann came to realize the great difficulty of building a self-replicating robot, and of the great cost in providing the robot with a "sea of parts" from which to build its replicant. Neumann wrote a paper entitled "The general and logical theory of automata" for the Hixon Symposium in 1948. Ulam was the one who suggested using a discrete system for creating a reductionist model of self-replication. Ulam and von Neumann created a method for calculating liquid motion in the late 1950s. The driving concept of the method was to consider a liquid as a group of discrete units and calculate the motion of each based on its neighbors' behaviors. Thus was born the first system of cellular automata. Like Ulam's lattice network, von Neumann's cellular automata are two-dimensional, with his self-replicator implemented algorithmically. The result was a universal copier and constructor working within a cellular automaton with a small neighborhood (only those cells that touch are neighbors; for von Neumann's cellular automata, only orthogonal cells), and with 29 states per cell. Von Neumann gave an existence proof that a particular pattern would make endless copies of itself within the given cellular universe by designing a 200,000 cell configuration that could do so. This design is known as the tessellation model, and is called a von Neumann universal constructor.

Motivated by questions in mathematical logic and in part by work on simulation games by Ulam, among others, John Conway began doing experiments in 1968 with a variety of different two-dimensional cellular automaton rules. Conway's initial goal was to define an interesting and unpredictable cellular automaton. According to Martin Gardner, Conway experimented with different rules, aiming for rules that would allow for patterns to "apparently" grow without limit, while keeping it difficult to prove that any given pattern would do so. Moreover, some "simple initial patterns" should "grow and change for a considerable period of time" before settling into a static configuration or a repeating loop. Conway later wrote that the basic motivation for Life was to create a "universal" cellular automaton.

The game made its first public appearance in the October 1970 issue of Scientific American, in Martin Gardner's "Mathematical Games" column, which was based on personal conversations with Conway. Theoretically, the Game of Life has the power of a universal Turing machine: anything that can be computed algorithmically can be computed within the Game of Life. Gardner wrote, "Because of Life's analogies with the rise, fall and alterations of a society of living organisms, it belongs to a growing class of what are called 'simulation games' (games that resemble real-life processes)."

Since its publication, the Game of Life has attracted much interest because of the surprising ways in which the patterns can evolve. It provides an example of emergence and self-organization. A version of Life that incorporates random fluctuations has been used in physics to study phase transitions and nonequilibrium dynamics. The game can also serve as a didactic analogy, used to convey the somewhat counter-intuitive notion that design and organization can spontaneously emerge in the absence of a designer. For example, philosopher Daniel Dennett has used the analogy of the Game of Life "universe" extensively to illustrate the possible evolution of complex philosophical constructs, such as consciousness and free will, from the relatively simple set of deterministic physical laws which might govern our universe.

The popularity of the Game of Life was helped by its coming into being at the same time as increasingly inexpensive computer access. The game could be run for hours on these machines, which would otherwise have remained unused at night. In this respect, it foreshadowed the later popularity of computer-generated fractals. For many, the Game of Life was simply a programming challenge: a fun way to use otherwise wasted CPU cycles. For some, however, the Game of Life had more philosophical connotations. It developed a cult following through the 1970s and beyond; current developments have gone so far as to create theoretic emulations of computer systems within the confines of a Game of Life board.

Examples of patterns

Many different types of patterns occur in the Game of Life, which are classified according to their behaviour. Common pattern types include: still lifes, which do not change from one generation to the next; oscillators, which return to their initial state after a finite number of generations; and spaceships, which translate themselves across the grid.

The earliest interesting patterns in the Game of Life were discovered without the use of computers. The simplest still lifes and oscillators were discovered while tracking the fates of various small starting configurations using graph paper, blackboards, and physical game boards, such as those used in Go. During this early research, Conway discovered that the R-pentomino failed to stabilize in a small number of generations. In fact, it takes 1103 generations to stabilize, by which time it has a population of 116 and has generated six escaping gliders; these were the first spaceships ever discovered.

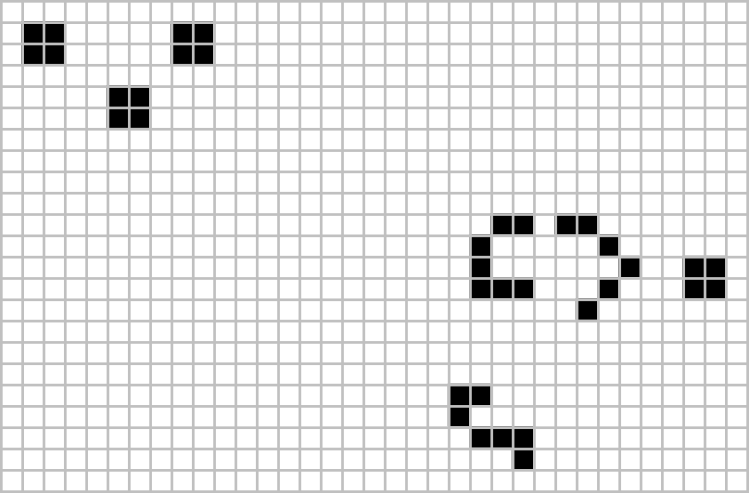

Frequently occurring examples (in that they emerge frequently from a random starting configuration of cells) of the three aforementioned pattern types are shown below, with live cells shown in black and dead cells in white. Period refers to the number of ticks a pattern must iterate through before returning to its initial configuration.

The pulsar is the most common period-3 oscillator. The great majority of naturally occurring oscillators have a period of 2, like the blinker and the toad, but oscillators of many periods are known to exist, and oscillators of periods 4, 8, 14, 15, 30, and a few others have been seen to arise from random initial conditions. Patterns which evolve for long periods before stabilizing are called Methuselahs, the first-discovered of which was the R-pentomino. Diehard is a pattern that eventually disappears, rather than stabilizing, after 130 generations, which is conjectured to be maximal for patterns with seven or fewer cells. Acorn takes 5206 generations to generate 633 cells, including 13 escaped gliders.

Conway originally conjectured that no pattern can grow indefinitely—i.e. that for any initial configuration with a finite number of living cells, the population cannot grow beyond some finite upper limit. In the game's original appearance in "Mathematical Games", Conway offered a prize of fifty dollars to the first person who could prove or disprove the conjecture before the end of 1970. The prize was won in November by a team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led by Bill Gosper; the "Gosper glider gun" produces its first glider on the 15th generation, and another glider every 30th generation from then on. For many years, this glider gun was the smallest one known. In 2015, a gun called the "Simkin glider gun", which releases a glider every 120th generation, was discovered that has fewer live cells but which is spread out across a larger bounding box at its extremities.

Smaller patterns were later found that also exhibit infinite growth. All three of the patterns shown below grow indefinitely. The first two create a single block-laying switch engine: a configuration that leaves behind two-by-two still life blocks as it translates itself across the game's universe. The third configuration creates two such patterns. The first has only ten live cells, which has been proven to be minimal. The second fits in a five-by-five square, and the third is only one cell high.

|

|

Later discoveries included other guns, which are stationary, and which produce gliders or other spaceships; puffer trains, which move along leaving behind a trail of debris; and rakes, which move and emit spaceships. Gosper also constructed the first pattern with an asymptotically optimal quadratic growth rate, called a breeder or lobster, which worked by leaving behind a trail of guns.

It is possible for gliders to interact with other objects in interesting ways. For example, if two gliders are shot at a block in a specific position, the block will move closer to the source of the gliders. If three gliders are shot in just the right way, the block will move farther away. This sliding block memory can be used to simulate a counter. It is possible to construct logic gates such as AND, OR, and NOT using gliders. It is possible to build a pattern that acts like a finite-state machine connected to two counters. This has the same computational power as a universal Turing machine, so the Game of Life is theoretically as powerful as any computer with unlimited memory and no time constraints; it is Turing complete. In fact, several different programmable computer architectures have been implemented in the Game of Life, including a pattern that simulates Tetris.

Furthermore, a pattern can contain a collection of guns that fire gliders in such a way as to construct new objects, including copies of the original pattern. A universal constructor can be built which contains a Turing complete computer, and which can build many types of complex objects, including more copies of itself.

In 2018, the first truly elementary knightship, Sir Robin, was discovered by Adam P. Goucher. A knightship is a spaceship that moves two squares left for every one square it moves down (like a knight in chess), as opposed to moving orthogonally or along a 45° diagonal. This is the first new spaceship movement pattern for an elementary spaceship found in forty-eight years. "Elementary" means that it cannot be decomposed into smaller interacting patterns such as gliders and still lifes.

Undecidability

Many patterns in the Game of Life eventually become a combination of still lifes, oscillators, and spaceships; other patterns may be called chaotic. A pattern may stay chaotic for a very long time until it eventually settles to such a combination.

The Game of Life is undecidable, which means that given an initial pattern and a later pattern, no algorithm exists that can tell whether the later pattern is ever going to appear. This is a corollary of the halting problem: the problem of determining whether a given program will finish running or continue to run forever from an initial input.

Indeed, since the Game of Life includes a pattern that is equivalent to a universal Turing machine (UTM), this deciding algorithm, if it existed, could be used to solve the halting problem by taking the initial pattern as the one corresponding to a UTM plus an input, and the later pattern as the one corresponding to a halting state of the UTM. It also follows that some patterns exist that remain chaotic forever. If this were not the case, one could progress the game sequentially until a non-chaotic pattern emerged, then compute whether a later pattern was going to appear.

Self-replication

On May 18, 2010, Andrew J. Wade announced a self-constructing pattern, dubbed "Gemini", that creates a copy of itself while destroying its parent. This pattern replicates in 34 million generations, and uses an instruction tape made of gliders oscillating between two stable configurations made of Chapman–Greene construction arms. These, in turn, create new copies of the pattern, and destroy the previous copy. Gemini is also a spaceship, and is the first spaceship constructed in the Game of Life that is an oblique spaceship, which is a spaceship that is neither orthogonal nor purely diagonal. In December 2015, diagonal versions of the Gemini were built.

On November 23, 2013, Dave Greene built the first replicator in the Game of Life that creates a complete copy of itself, including the instruction tape.

In October 2018, Adam P. Goucher finished his construction of the 0E0P metacell, a metacell capable of self-replication. This differed from previous metacells, such as the OTCA metapixel by Brice Due, which only worked with already constructed copies near them. The 0E0P metacell works by using construction arms to create copies that simulate the programmed rule. The actual simulation of the Game of Life or other Moore neighbourhood rules is done by simulating an equivalent rule using the von Neumann neighbourhood with more states. The name 0E0P is short for "Zero Encoded by Zero Population", which indicates that instead of a metacell being in an "off" state simulating empty space, the 0E0P metacell removes itself when the cell enters that state, leaving a blank space.

Iteration

From most random initial patterns of living cells on the grid, observers will find the population constantly changing as the generations tick by. The patterns that emerge from the simple rules may be considered a form of mathematical beauty. Small isolated subpatterns with no initial symmetry tend to become symmetrical. Once this happens, the symmetry may increase in richness, but it cannot be lost unless a nearby subpattern comes close enough to disturb it. In a very few cases, the society eventually dies out, with all living cells vanishing, though this may not happen for a great many generations. Most initial patterns eventually burn out, producing either stable figures or patterns that oscillate forever between two or more states; many also produce one or more gliders or spaceships that travel indefinitely away from the initial location. Because of the nearest-neighbour based rules, no information can travel through the grid at a greater rate than one cell per unit time, so this velocity is said to be the cellular automaton speed of light and denoted c.

Algorithms

Early patterns with unknown futures, such as the R-pentomino, led computer programmers to write programs to track the evolution of patterns in the Game of Life. Most of the early algorithms were similar: they represented the patterns as two-dimensional arrays in computer memory. Typically, two arrays are used: one to hold the current generation, and one to calculate its successor. Often 0 and 1 represent dead and live cells, respectively. A nested for loop considers each element of the current array in turn, counting the live neighbours of each cell to decide whether the corresponding element of the successor array should be 0 or 1. The successor array is displayed. For the next iteration, the arrays may swap roles so that the successor array in the last iteration becomes the current array in the next iteration, or one may copy the values of the second array into the first array then update the second array from the first array again.

A variety of minor enhancements to this basic scheme are possible, and there are many ways to save unnecessary computation. A cell that did not change at the last time step, and none of whose neighbours changed, is guaranteed not to change at the current time step as well, so a program that keeps track of which areas are active can save time by not updating inactive zones.

To avoid decisions and branches in the counting loop, the rules can be rearranged from an egocentric approach of the inner field regarding its neighbours to a scientific observer's viewpoint: if the sum of all nine fields in a given neighbourhood is three, the inner field state for the next generation will be life; if the all-field sum is four, the inner field retains its current state; and every other sum sets the inner field to death.

To save memory, the storage can be reduced to one array plus two line buffers. One line buffer is used to calculate the successor state for a line, then the second line buffer is used to calculate the successor state for the next line. The first buffer is then written to its line and freed to hold the successor state for the third line. If a toroidal array is used, a third buffer is needed so that the original state of the first line in the array can be saved until the last line is computed.

In principle, the Game of Life field is infinite, but computers have finite memory. This leads to problems when the active area encroaches on the border of the array. Programmers have used several strategies to address these problems. The simplest strategy is to assume that every cell outside the array is dead. This is easy to program but leads to inaccurate results when the active area crosses the boundary. A more sophisticated trick is to consider the left and right edges of the field to be stitched together, and the top and bottom edges also, yielding a toroidal array. The result is that active areas that move across a field edge reappear at the opposite edge. Inaccuracy can still result if the pattern grows too large, but there are no pathological edge effects. Techniques of dynamic storage allocation may also be used, creating ever-larger arrays to hold growing patterns. The Game of Life on a finite field is sometimes explicitly studied; some implementations, such as Golly, support a choice of the standard infinite field, a field infinite only in one dimension, or a finite field, with a choice of topologies such as a cylinder, a torus, or a Möbius strip.

Alternatively, programmers may abandon the notion of representing the Game of Life field with a two-dimensional array, and use a different data structure, such as a vector of coordinate pairs representing live cells. This allows the pattern to move about the field unhindered, as long as the population does not exceed the size of the live-coordinate array. The drawback is that counting live neighbours becomes a hash-table lookup or search operation, slowing down simulation speed. With more sophisticated data structures this problem can also be largely solved.

For exploring large patterns at great time depths, sophisticated algorithms such as Hashlife may be useful. There is also a method for implementation of the Game of Life and other cellular automata using arbitrary asynchronous updates whilst still exactly emulating the behaviour of the synchronous game. Source code examples that implement the basic Game of Life scenario in various programming languages, including C, C++, Java and Python can be found at Rosetta Code.

Variations

Since the Game of Life's inception, new, similar cellular automata have been developed. The standard Game of Life is symbolized as B3/S23. A cell is born if it has exactly three neighbours, survives if it has two or three living neighbours, and dies otherwise. The first number, or list of numbers, is what is required for a dead cell to be born. The second set is the requirement for a live cell to survive to the next generation. Hence B6/S16 means "a cell is born if there are six neighbours, and lives on if there are either one or six neighbours". Cellular automata on a two-dimensional grid that can be described in this way are known as Life-like cellular automata. Another common Life-like automaton, Highlife, is described by the rule B36/S23, because having six neighbours, in addition to the original game's B3/S23 rule, causes a birth. HighLife is best known for its frequently occurring replicators.

Additional Life-like cellular automata exist. The vast majority of these 218 different rules produce universes that are either too chaotic or too desolate to be of interest, but a large subset do display interesting behavior. A further generalization produces the isotropic rulespace, with 2102 possible cellular automaton rules (the Game of Life again being one of them). These are rules that use the same square grid as the Life-like rules and the same eight-cell neighbourhood, and are likewise invariant under rotation and reflection. However, in isotropic rules, the positions of neighbour cells relative to each other may be taken into account in determining a cell's future state—not just the total number of those neighbours.

Some variations on the Game of Life modify the geometry of the universe as well as the rule. The above variations can be thought of as a two-dimensional square, because the world is two-dimensional and laid out in a square grid. One-dimensional square variations, known as elementary cellular automata, and three-dimensional square variations have been developed, as have two-dimensional hexagonal and triangular variations. A variant using aperiodic tiling grids has also been made.

Conway's rules may also be generalized such that instead of two states, live and dead, there are three or more. State transitions are then determined either by a weighting system or by a table specifying separate transition rules for each state; for example, Mirek's Cellebration's multi-coloured Rules Table and Weighted Life rule families each include sample rules equivalent to the Game of Life.

Patterns relating to fractals and fractal systems may also be observed in certain Life-like variations. For example, the automaton B1/S12 generates four very close approximations to the Sierpinski triangle when applied to a single live cell. The Sierpinski triangle can also be observed in the Game of Life by examining the long-term growth of an infinitely long single-cell-thick line of live cells, as well as in Highlife, Seeds (B2/S), and Wolfram's Rule 90.

Immigration is a variation that is very similar to the Game of Life, except that there are two on states, often expressed as two different colours. Whenever a new cell is born, it takes on the on state that is the majority in the three cells that gave it birth. This feature can be used to examine interactions between spaceships and other objects within the game. Another similar variation, called QuadLife, involves four different on states. When a new cell is born from three different on neighbours, it takes the fourth value, and otherwise, like Immigration, it takes the majority value. Except for the variation among on cells, both of these variations act identically to the Game of Life.

Music

Various musical composition techniques use the Game of Life, especially in MIDI sequencing. A variety of programs exist for creating sound from patterns generated in the Game of Life.

Notable programs

Computers have been used to follow Game of Life configurations since it was first publicized. When John Conway was first investigating how various starting configurations developed, he tracked them by hand using a go board with its black and white stones. This was tedious and prone to errors. The first interactive Game of Life program was written in an early version of ALGOL 68C for the PDP-7 by M. J. T. Guy and S. R. Bourne. The results were published in the October 1970 issue of Scientific American, along with the statement: "Without its help, some discoveries about the game would have been difficult to make."

A color version of the Game of Life was written by Ed Hall in 1976 for Cromemco microcomputers, and a display from that program filled the cover of the June 1976 issue of Byte. The advent of microcomputer-based color graphics from Cromemco has been credited with a revival of interest in the game.

Two early implementations of the Game of Life on home computers were by Malcolm Banthorpe written in BBC BASIC. The first was in the January 1984 issue of Acorn User magazine, and Banthorpe followed this with a three-dimensional version in the May 1984 issue. Susan Stepney, Professor of Computer Science at the University of York, followed this up in 1988 with Life on the Line, a program that generated one-dimensional cellular automata.

There are now thousands of Game of Life programs online, so a full list will not be provided here. The following is a small selection of programs with some special claim to notability, such as popularity or unusual features. Most of these programs incorporate a graphical user interface for pattern editing and simulation, the capability for simulating multiple rules including the Game of Life, and a large library of interesting patterns in the Game of Life and other cellular automaton rules.

- Golly is a cross-platform (Windows, Macintosh, Linux, iOS, and Android) open-source simulation system for the Game of Life and other cellular automata (including all Life-like cellular automata, the Generations family of cellular automata from Mirek's Cellebration, and John von Neumann's 29-state cellular automaton) by Andrew Trevorrow and Tomas Rokicki. It includes the Hashlife algorithm for extremely fast generation, and Lua or Python scriptability for both editing and simulation.

- Mirek's Cellebration is a freeware one- and two-dimensional cellular automata viewer, explorer, and editor for Windows. It includes powerful facilities for simulating and viewing a wide variety of cellular automaton rules, including the Game of Life, and a scriptable editor.

- Xlife is a cellular-automaton laboratory by Jon Bennett. The standard UNIX X11 Game of Life simulation application for a long time, it has also been ported to Windows. It can handle cellular automaton rules with the same neighbourhood as the Game of Life, and up to eight possible states per cell.

- Dr. Blob's Organism is a Shoot 'em up based on Conway's Life. In the game, Life continually generates on a group of cells within a "petri dish". The patterns formed are smoothed and rounded to look like a growing amoeba spewing smaller ones (actually gliders). Special "probes" zap the "blob" to keep it from overflowing the dish while destroying its nucleus.

Google implemented an easter egg of the Game of Life in 2012. Users who search for the term are shown an implementation of the game in the search results page.