Snell's law (also known as Snell–Descartes law and ibn-Sahl law and the law of refraction) is a formula used to describe the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction, when referring to light or other waves passing through a boundary between two different isotropic media, such as water, glass, or air. This law was named after the Dutch astronomer and mathematician Willebrord Snellius (also called Snell).

In optics, the law is used in ray tracing to compute the angles of incidence or refraction, and in experimental optics to find the refractive index of a material. The law is also satisfied in meta-materials, which allow light to be bent "backward" at a negative angle of refraction with a negative refractive index.

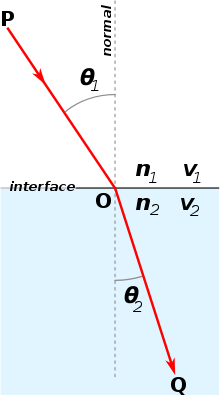

Snell's law states that, for a given pair of media, the ratio of the sines of the angle of incidence θ1 and angle of refraction θ2 is equal to the ratio of phase velocities (v1 / v2) in the two media, or equivalently, to the refractive indices (n2 / n1) of the two media.

The law follows from Fermat's principle of least time, which in turn follows from the propagation of light as waves.

History

Ptolemy, in Alexandria, Egypt, had found a relationship regarding refraction angles, but it was inaccurate for angles that were not small. Ptolemy was confident he had found an accurate empirical law, partially as a result of slightly altering his data to fit theory (see: confirmation bias). Alhazen, in his Book of Optics (1021), came closer to discovering the law of refraction, though he did not take this step.

The law eventually named after Snell was first accurately described by the Persian scientist Ibn Sahl at the Baghdad court in 984. In the manuscript On Burning Mirrors and Lenses, Sahl used the law to derive lens shapes that focus light with no geometric aberrations.

The law was rediscovered by Thomas Harriot in 1602, who however did not publish his results although he had corresponded with Kepler on this very subject. In 1621, the Dutch astronomer Willebrord Snellius (1580–1626)—Snell—derived a mathematically equivalent form, that remained unpublished during his lifetime. René Descartes independently derived the law using heuristic momentum conservation arguments in terms of sines in his 1637 essay Dioptrique, and used it to solve a range of optical problems. Rejecting Descartes' solution, Pierre de Fermat arrived at the same solution based solely on his principle of least time. Descartes assumed the speed of light was infinite, yet in his derivation of Snell's law he also assumed the denser the medium, the greater the speed of light. Fermat supported the opposing assumptions, i.e., the speed of light is finite, and his derivation depended upon the speed of light being slower in a denser medium. Fermat's derivation also utilized his invention of adequality, a mathematical procedure equivalent to differential calculus, for finding maxima, minima, and tangents.

In his influential mathematics book Geometry, Descartes solves a problem that was worked on by Apollonius of Perga and Pappus of Alexandria. Given n lines L and a point P(L) on each line, find the locus of points Q such that the lengths of the line segments QP(L) satisfy certain conditions. For example, when n = 4, given the lines a, b, c, and d and a point A on a, B on b, and so on, find the locus of points Q such that the product QA*QB equals the product QC*QD. When the lines are not all parallel, Pappus showed that the loci are conics, but when Descartes considered larger n, he obtained cubic and higher degree curves. To show that the cubic curves were interesting, he showed that they arose naturally in optics from Snell's law.

According to Dijksterhuis, "In De natura lucis et proprietate (1662) Isaac Vossius said that Descartes had seen Snell's paper and concocted his own proof. We now know this charge to be undeserved but it has been adopted many times since." Both Fermat and Huygens repeated this accusation that Descartes had copied Snell. In French, Snell's Law is called "la loi de Descartes" or "loi de Snell-Descartes."

In his 1678 Traité de la Lumière, Christiaan Huygens showed how Snell's law of sines could be explained by, or derived from, the wave nature of light, using what we have come to call the Huygens–Fresnel principle.

With the development of modern optical and electromagnetic theory, the ancient Snell's law was brought into a new stage. In 1962, Bloembergen showed that at the boundary of nonlinear medium, the Snell's law should be written in a general form. In 2008 and 2011, plasmonic metasurfaces were also demonstrated to change the reflection and refraction directions of light beam.

Explanation

Snell's law is used to determine the direction of light rays through refractive media with varying indices of refraction. The indices of refraction of the media, labeled , and so on, are used to represent the factor by which a light ray's speed decreases when traveling through a refractive medium, such as glass or water, as opposed to its velocity in a vacuum.

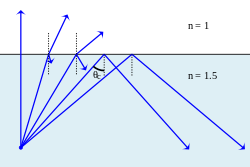

As light passes the border between media, depending upon the relative refractive indices of the two media, the light will either be refracted to a lesser angle, or a greater one. These angles are measured with respect to the normal line, represented perpendicular to the boundary. In the case of light traveling from air into water, light would be refracted towards the normal line, because the light is slowed down in water; light traveling from water to air would refract away from the normal line.

Refraction between two surfaces is also referred to as reversible because if all conditions were identical, the angles would be the same for light propagating in the opposite direction.

Snell's law is generally true only for isotropic or specular media (such as glass). In anisotropic media such as some crystals, birefringence may split the refracted ray into two rays, the ordinary or o-ray which follows Snell's law, and the other extraordinary or e-ray which may not be co-planar with the incident ray.

When the light or other wave involved is monochromatic, that is, of a single frequency, Snell's law can also be expressed in terms of a ratio of wavelengths in the two media, and :

Derivations and formula

Snell's law can be derived in various ways.

Derivation from Fermat's principle

Snell's law can be derived from Fermat's principle, which states that the light travels the path which takes the least time. By taking the derivative of the optical path length, the stationary point is found giving the path taken by the light. (There are situations of light violating Fermat's principle by not taking the least time path, as in reflection in a (spherical) mirror.) In a classic analogy, the area of lower refractive index is replaced by a beach, the area of higher refractive index by the sea, and the fastest way for a rescuer on the beach to get to a drowning person in the sea is to run along a path that follows Snell's law.

As shown in the figure to the right, assume the refractive index of medium 1 and medium 2 are and respectively. Light enters medium 2 from medium 1 via point O.

is the angle of incidence, is the angle of refraction with respect to the normal.

The phase velocities of light in medium 1 and medium 2 are

- and

- respectively.

is the speed of light in vacuum.

Let T be the time required for the light to travel from point Q through point O to point P.

where a, b, l and x are as denoted in the right-hand figure, x being the varying parameter.

To minimize it, one can differentiate :

- (stationary point)

Note that

and

Therefore,

Derivation from Huygens's principle

Alternatively, Snell's law can be derived using interference of all possible paths of light wave from source to observer—it results in destructive interference everywhere except extrema of phase (where interference is constructive)—which become actual paths.

Derivation from Maxwell's equations

Another way to derive Snell's Law involves an application of the general boundary conditions of Maxwell equations for electromagnetic radiation and induction.

Derivation from conservation of energy and momentum

Yet another way to derive Snell's law is based on translation symmetry considerations. For example, a homogeneous surface perpendicular to the z direction cannot change the transverse momentum. Since the propagation vector is proportional to the photon's momentum, the transverse propagation direction must remain the same in both regions. Assume without loss of generality a plane of incidence in the plane . Using the well known dependence of the wavenumber on the refractive index of the medium, we derive Snell's law immediately.

where is the wavenumber in vacuum. Although no surface is truly homogeneous at the atomic scale, full translational symmetry is an excellent approximation whenever the region is homogeneous on the scale of the light wavelength.

Vector form

Given a normalized light vector (pointing from the light source toward the surface) and a normalized plane normal vector , one can work out the normalized reflected and refracted rays, via the cosines of the angle of incidence and angle of refraction , without explicitly using the sine values or any trigonometric functions or angles:

Note: must be positive, which it will be if is the normal vector that points from the surface toward the side where the light is coming from, the region with index . If is negative, then points to the side without the light, so start over with replaced by its negative.

This reflected direction vector points back toward the side of the surface where the light came from.

Now apply Snell's law to the ratio of sines to derive the formula for the refracted ray's direction vector:

The formula may appear simpler in terms of renamed simple values and , avoiding any appearance of trig function names or angle names:

Example:

The cosine values may be saved and used in the Fresnel equations for working out the intensity of the resulting rays.

Total internal reflection is indicated by a negative radicand in the equation for , which can only happen for rays crossing into a less-dense medium ().

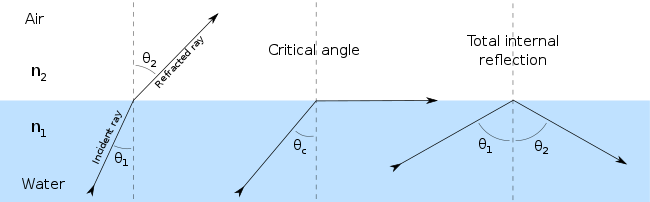

Total internal reflection and critical angle

When light travels from a medium with a higher refractive index to one with a lower refractive index, Snell's law seems to require in some cases (whenever the angle of incidence is large enough) that the sine of the angle of refraction be greater than one. This of course is impossible, and the light in such cases is completely reflected by the boundary, a phenomenon known as total internal reflection. The largest possible angle of incidence which still results in a refracted ray is called the critical angle; in this case the refracted ray travels along the boundary between the two media.

For example, consider a ray of light moving from water to air with an angle of incidence of 50°. The refractive indices of water and air are approximately 1.333 and 1, respectively, so Snell's law gives us the relation

which is impossible to satisfy. The critical angle θcrit is the value of θ1 for which θ2 equals 90°:

Dispersion

In many wave-propagation media, wave velocity changes with frequency or wavelength of the waves; this is true of light propagation in most transparent substances other than a vacuum. These media are called dispersive. The result is that the angles determined by Snell's law also depend on frequency or wavelength, so that a ray of mixed wavelengths, such as white light, will spread or disperse. Such dispersion of light in glass or water underlies the origin of rainbows and other optical phenomena, in which different wavelengths appear as different colors.

In optical instruments, dispersion leads to chromatic aberration; a color-dependent blurring that sometimes is the resolution-limiting effect. This was especially true in refracting telescopes, before the invention of achromatic objective lenses.

Lossy, absorbing, or conducting media

In a conducting medium, permittivity and index of refraction are complex-valued. Consequently, so are the angle of refraction and the wave-vector. This implies that, while the surfaces of constant real phase are planes whose normals make an angle equal to the angle of refraction with the interface normal, the surfaces of constant amplitude, in contrast, are planes parallel to the interface itself. Since these two planes do not in general coincide with each other, the wave is said to be inhomogeneous. The refracted wave is exponentially attenuated, with exponent proportional to the imaginary component of the index of refraction.