The Holocene extinction, or Anthropocene extinction, is the ongoing extinction event during the Holocene epoch. The extinctions span numerous families of plants and animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, and affecting not just terrestrial species but also large sectors of marine life. With widespread degradation of biodiversity hotspots, such as coral reefs and rainforests, as well as other areas, the vast majority of these extinctions are thought to be undocumented, as the species are undiscovered at the time of their extinction, which goes unrecorded. The current rate of extinction of species is estimated at 100 to 1,000 times higher than natural background extinction rates, and is increasing.

During the past 100–200 years, biodiversity loss and species extinction have accelerated, to the point that most conservation biologists now believe that human activity has either produced a period of mass extinction, or is on the cusp of doing so. As such, after the "Big Five" mass extinctions, the Holocene extinction event has also been referred to as the sixth mass extinction or sixth extinction; given the recent recognition of the Capitanian mass extinction, the term seventh mass extinction has also been proposed for the Holocene extinction event.

The Holocene extinction follows the extinction of many large (megafaunal) animals during the preceding Late Pleistocene as part of the Quaternary extinction event. Megafauna outside of the African mainland, which did not evolve alongside humans, proved highly sensitive to the introduction of human predation, and many died out shortly after early humans began spreading and hunting across the Earth. Many African species have also gone extinct in the Holocene, along with species in North America, South America, and Australia, but – with some exceptions – the megafauna of the Eurasian mainland was largely unaffected until a few hundred years ago. These extinctions, occurring near the Pleistocene–Holocene boundary, are sometimes referred to as the Quaternary extinction event.

The most popular theory is that human overhunting of species added to existing stress conditions as the Holocene extinction coincides with human colonization of many new areas around the world. Although there is debate regarding how much human predation and habitat loss affected their decline, certain population declines have been directly correlated with the onset of human activity, such as the extinction events of New Zealand and Hawaii. Aside from humans, climate change may have been a driving factor in the megafaunal extinctions, especially at the end of the Pleistocene.

In the twentieth century, human numbers quadrupled, and the size of the global economy increased twenty-five-fold. This Great Acceleration or Anthropocene epoch has also accelerated species extinction. Ecologically, humanity is now an unprecedented "global superpredator", which consistently preys on the adults of other apex predators, takes over other species' essential habitats and displaces them, and has worldwide effects on food webs. There have been extinctions of species on every land mass and in every ocean: there are many famous examples within Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, North and South America, and on smaller islands.

Overall, the Holocene extinction can be linked to the human impact on the environment. The Holocene extinction continues into the 21st century, with human population growth, increasing per capita consumption (especially by the super-affluent), and meat production, among others, being the primary drivers of mass extinction. Deforestation, overfishing, ocean acidification, the destruction of wetlands, and the decline in amphibian populations, among others, are a few broader examples of global biodiversity loss.

Background

Mass extinctions are characterized by the loss of at least 75% of species within a geologically short period of time. The Holocene extinction is also known as the "sixth extinction", as it is possibly the sixth mass extinction event, after the Ordovician–Silurian extinction events, the Late Devonian extinction, the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, and the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

The Holocene is the current geological epoch.

Overview

There is no general agreement on where the Holocene, or anthropogenic, extinction begins, and the Quaternary extinction event, which includes climate change resulting in the end of the last ice age, ends, or if they should be considered separate events at all. The Holocene extinction is mainly caused by human activities. Some have suggested that anthropogenic extinctions may have begun as early as when the first modern humans spread out of Africa between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago; this is supported by rapid megafaunal extinction following recent human colonisation in Australia, New Zealand and Madagascar. In many cases, it is suggested that even minimal hunting pressure was enough to wipe out large fauna, particularly on geographically isolated islands. Only during the most recent parts of the extinction have plants also suffered large losses.

Extinction rate

The contemporary rate of extinction of species is estimated at 100 to 1,000 times higher than the background extinction rate, the historically typical rate of extinction (in terms of the natural evolution of the planet); also, the current rate of extinction is 10 to 100 times higher than in any of the previous mass extinctions in the history of Earth. One scientist estimates the current extinction rate may be 10,000 times the background extinction rate, although most scientists predict a much lower extinction rate than this outlying estimate. Theoretical ecologist Stuart Pimm stated that the extinction rate for plants is 100 times higher than normal.

Some contend that contemporary extinction has yet to reach the level of the previous five mass extinctions, and that this comparison downplays how severe the first five mass extinctions were. John Briggs argues that there is inadequate data to determine the real rate of extinctions, and shows that estimates of current species extinctions varies enormously, ranging from 1.5 species to 40,000 species going extinct due to human activities each year. Both papers from Barnosky et al. (2011) and Hull et al. (2015) point out that the real rate of extinction during previous mass extinctions is unknown, both as only some organisms leave fossil remains, and as the temporal resolution of the fossil layer is larger than the time frame of the extinction events. However, all these authors agree that there is a modern biodiversity crisis with population declines affecting numerous species, and that a future anthropogenic mass extinction event is a big risk. The 2011 study by Barnosky et al. confirms that "current extinction rates are higher than would be expected from the fossil record" and adds that anthropogenic ecological stressors, including climate change, habitat fragmentation, pollution, overfishing, overhunting, invasive species and expanding human biomass will intensify and accelerate extinction rates in the future without significant mitigation efforts.

In The Future of Life (2002), Edward Osborne Wilson of Harvard calculated that, if the current rate of human disruption of the biosphere continues, one-half of Earth's higher lifeforms will be extinct by 2100. A 1998 poll conducted by the American Museum of Natural History found that 70% of biologists acknowledge an ongoing anthropogenic extinction event.

In a pair of studies published in 2015, extrapolation from observed extinction of Hawaiian snails led to the conclusion that 7% of all species on Earth may have been lost already. A 2021 study published in the journal Frontiers in Forests and Global Change found that only around 3% of the planet's terrestrial surface is ecologically and faunally intact, meaning areas with healthy populations of native animal species and little to no human footprint.

The 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, published by the United Nations' Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), posits that roughly one million species of plants and animals face extinction within decades as the result of human actions. Organized human existence is jeopardized by increasingly rapid destruction of the systems that support life on Earth, according to the report, the result of one of the most comprehensive studies of the health of the planet ever conducted. Moreover, the 2021 Economics of Biodiversity review, published by the UK government, asserts that "biodiversity is declining faster than at any time in human history." According to a 2022 study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, a survey of more than 3,000 experts says that the extent of the mass extinction might be greater than previously thought, and estimates that roughly 30% of species "have been globally threatened or driven extinct since the year 1500." In a 2022 report, IPBES listed unsustainable fishing, hunting and logging as being some of the primary drivers of the global extinction crisis. A 2022 study published in Science Advances suggests that between 13% and 27% of terrestrial vertebrate species will go extinct by 2100, much of this through anthropogenic land conversion, climate change and co-extinctions.

Attribution

We are currently, in a systematic manner, exterminating all non-human living beings.

—Anne Larigauderie, IPBES executive secretary

There is widespread consensus among scientists that human activity is accelerating the extinction of many animal species through the destruction of habitats, the consumption of animals as resources, and the elimination of species that humans view as threats or competitors. Rising extinction trends impacting numerous animal groups including mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians have prompted some scientists to declare a biodiversity crisis.

Scientific debate

Characterisation of recent extinction as a mass extinction has been debated among scientists. Stuart Pimm, for example, asserts that the sixth mass extinction "is something that hasn't happened yet – we are on the edge of it." Several studies posit that the earth has entered a sixth mass extinction event, including a 2015 paper by Barnosky et al. and a November 2017 statement titled "World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice", led by eight authors and signed by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries which asserted that, among other things, "we have unleashed a mass extinction event, the sixth in roughly 540 million years, wherein many current life forms could be extirpated or at least committed to extinction by the end of this century." The World Wide Fund for Nature's 2020 Living Planet Report says that wildlife populations have declined by 68% since 1970 as a result of overconsumption, population growth and intensive farming, which is further evidence that humans have unleashed a sixth mass extinction event; however, this finding has been disputed by one 2020 study, which posits that this major decline was primarily driven by a few extreme outlier populations, and that when these outliers are removed, the trend shifts to that of a decline between the 1980s and 2000s, but a roughly positive trend after 2000. A 2021 report in Frontiers in Conservation Science which cites both of the aforementioned studies, says "population sizes of vertebrate species that have been monitored across years have declined by an average of 68% over the last five decades, with certain population clusters in extreme decline, thus presaging the imminent extinction of their species," and asserts "that we are already on the path of a sixth major extinction is now scientifically undeniable." A January 2022 review article published in Biological Reviews builds upon previous studies documenting biodiversity decline to assert that a sixth mass extinction event caused by anthropogenic activity is currently underway. A December 2022 study published in Science Advances states that "the planet has entered the sixth mass extinction" and warns that current anthropogenic trends, particularly regarding climate and land-use changes, could result in the loss of more than a tenth of plant and animal species by the end of the century.

According to the UNDP's 2020 Human Development Report, The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene:

The planet's biodiversity is plunging, with a quarter of species facing extinction, many within decades. Numerous experts believe we are living through, or on the cusp of, a mass species extinction event, the sixth in the history of the planet and the first to be caused by a single organism—us.

The 2022 Living Planet Report found that vertebrate wildlife populations have plummeted by an average of almost 70% since 1970, with agriculture and fishing being the primary drivers of this decline.

Some scientists, including Rodolfo Dirzo and Paul R. Ehrlich, contend that the sixth mass extinction is largely unknown to most people globally, and is also misunderstood by many in the scientific community. They say it is not the disappearance of species, which gets the most attention, that is at the heart of the crisis, but "the existential threat of myriad population extinctions."

Anthropocene

The abundance of species extinctions considered anthropogenic, or due to human activity, has sometimes (especially when referring to hypothesized future events) been collectively called the "Anthropocene extinction". Anthropocene is a term introduced in 2000. Some now postulate that a new geological epoch has begun, with the most abrupt and widespread extinction of species since the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago.

The term "anthropocene" is being used more frequently by scientists, and some commentators may refer to the current and projected future extinctions as part of a longer Holocene extinction. The Holocene–Anthropocene boundary is contested, with some commentators asserting significant human influence on climate for much of what is normally regarded as the Holocene Epoch. Other commentators place the Holocene–Anthropocene boundary at the industrial revolution and also say that "[f]ormal adoption of this term in the near future will largely depend on its utility, particularly to earth scientists working on late Holocene successions."

It has been suggested that human activity has made the period starting from the mid-20th century different enough from the rest of the Holocene to consider it a new geological epoch, known as the Anthropocene, a term which was considered for inclusion in the timeline of Earth's history by the International Commission on Stratigraphy in 2016. In order to constitute the Holocene as an extinction event, scientists must determine exactly when anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions began to measurably alter natural atmospheric levels on a global scale, and when these alterations caused changes to global climate. Using chemical proxies from Antarctic ice cores, researchers have estimated the fluctuations of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) gases in the Earth's atmosphere during the late Pleistocene and Holocene epochs. Estimates of the fluctuations of these two gases in the atmosphere, using chemical proxies from Antarctic ice cores, generally indicate that the peak of the Anthropocene occurred within the previous two centuries: typically beginning with the Industrial Revolution, when the highest greenhouse gas levels were recorded.

Human ecology

A 2015 article in Science suggested that humans are unique in ecology as an unprecedented "global superpredator", regularly preying on large numbers of fully grown terrestrial and marine apex predators, and with a great deal of influence over food webs and climatic systems worldwide. Although significant debate exists as to how much human predation and indirect effects contributed to prehistoric extinctions, certain population crashes have been directly correlated with human arrival. Human activity has been the main cause of mammalian extinctions since the Late Pleistocene. A 2018 study published in PNAS found that since the dawn of human civilization, the biomass of wild mammals has decreased by 83%. The biomass decrease is 80% for marine mammals, 50% for plants and 15% for fish. Currently, livestock make up 60% of the biomass of all mammals on earth, followed by humans (36%) and wild mammals (4%). As for birds, 70% are domesticated, such as poultry, whereas only 30% are wild.

Historic extinction

Human activity

Activities contributing to extinctions

Extinction of animals, plants, and other organisms caused by human actions may go as far back as the late Pleistocene, over 12,000 years ago. There is a correlation between megafaunal extinction and the arrival of humans. Over the past 125,000 years, the average body size of wildlife has fallen by 14% as human actions eradicated megafauna on all continents with the exception of Africa.

Human civilization was founded on and grew from agriculture. The more land used for farming, the greater the population a civilization could sustain, and subsequent popularization of farming led to widespread habitat conversion.

Habitat destruction by humans, thus replacing the original local ecosystems, is a major driver of extinction. The sustained conversion of biodiversity rich forests and wetlands into poorer fields and pastures (of lesser carrying capacity for wild species), over the last 10,000 years, has considerably reduced the Earth's carrying capacity for wild birds and mammals, among other organisms, in both population size and species count.

Other, related human causes of the extinction event include deforestation, hunting, pollution, the introduction in various regions of non-native species, and the widespread transmission of infectious diseases spread through livestock and crops.

Agriculture and climate change

Recent investigations into the practice of landscape burning during the Neolithic Revolution have a major implication for the current debate about the timing of the Anthropocene and the role that humans may have played in the production of greenhouse gases prior to the Industrial Revolution. Studies of early hunter-gatherers raise questions about the current use of population size or density as a proxy for the amount of land clearance and anthropogenic burning that took place in pre-industrial times. Scientists have questioned the correlation between population size and early territorial alterations. Ruddiman and Ellis' research paper in 2009 makes the case that early farmers involved in systems of agriculture used more land per capita than growers later in the Holocene, who intensified their labor to produce more food per unit of area (thus, per laborer); arguing that agricultural involvement in rice production implemented thousands of years ago by relatively small populations created significant environmental impacts through large-scale means of deforestation.

While a number of human-derived factors are recognized as contributing to rising atmospheric concentrations of CH4 (methane) and CO2 (carbon dioxide), deforestation and territorial clearance practices associated with agricultural development may have contributed most to these concentrations globally in earlier millennia. Scientists that are employing a variance of archaeological and paleoecological data argue that the processes contributing to substantial human modification of the environment spanned many thousands of years on a global scale and thus, not originating as late as the Industrial Revolution. Palaeoclimatologist William Ruddiman has argued that in the early Holocene 11,000 years ago, atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane levels fluctuated in a pattern which was different from the Pleistocene epoch before it. He argued that the patterns of the significant decline of CO2 levels during the last ice age of the Pleistocene inversely correlate to the Holocene where there have been dramatic increases of CO2 around 8000 years ago and CH4 levels 3000 years after that. The correlation between the decrease of CO2 in the Pleistocene and the increase of it during the Holocene implies that the causation of this spark of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere was the growth of human agriculture during the Holocene.

Climate change

One of the main theories explaining early Holocene extinctions is historic climate change. The climate change theory has suggested that a change in climate near the end of the late Pleistocene stressed the megafauna to the point of extinction. Some scientists favor abrupt climate change as the catalyst for the extinction of the mega-fauna at the end of the Pleistocene, most who believe increased hunting from early modern humans also played a part, with others even suggesting that the two interacted. However, the annual mean temperature of the current interglacial period for the last 10,000 years is no higher than that of previous interglacial periods, yet some of the same megafauna survived similar temperature increases. In the Americas, a controversial explanation for the shift in climate is presented under the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis, which states that the impact of comets cooled global temperatures.

A 2020 study published in Science Advances found that human population size and/or specific human activities, not climate change, caused rapidly rising global mammal extinction rates during the past 126,000 years. Around 96% of all mammalian extinctions over this time period are attributable to human impacts. According to Tobias Andermann, lead author of the study, "these extinctions did not happen continuously and at constant pace. Instead, bursts of extinctions are detected across different continents at times when humans first reached them. More recently, the magnitude of human driven extinctions has picked up the pace again, this time on a global scale."

Megafaunal extinction

Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance. They do so by their movement between the time they consume the nutrient and the time they release it through elimination (or, to a much lesser extent, through decomposition after death). In South America's Amazon Basin, it is estimated that such lateral diffusion was reduced over 98% following the megafaunal extinctions that occurred roughly 12,500 years ago. Given that phosphorus availability is thought to limit productivity in much of the region, the decrease in its transport from the western part of the basin and from floodplains (both of which derive their supply from the uplift of the Andes) to other areas is thought to have significantly impacted the region's ecology, and the effects may not yet have reached their limits. The extinction of the mammoths allowed grasslands they had maintained through grazing habits to become birch forests. The new forest and the resulting forest fires may have induced climate change. Such disappearances might be the result of the proliferation of modern humans.

Large populations of megaherbivores have the potential to contribute greatly to the atmospheric concentration of methane, which is an important greenhouse gas. Modern ruminant herbivores produce methane as a byproduct of foregut fermentation in digestion, and release it through belching or flatulence. Today, around 20% of annual methane emissions come from livestock methane release. In the Mesozoic, it has been estimated that sauropods could have emitted 520 million tons of methane to the atmosphere annually, contributing to the warmer climate of the time (up to 10 °C warmer than at present). This large emission follows from the enormous estimated biomass of sauropods, and because methane production of individual herbivores is believed to be almost proportional to their mass.

Recent studies have indicated that the extinction of megafaunal herbivores may have caused a reduction in atmospheric methane. One study examined the methane emissions from the bison that occupied the Great Plains of North America before contact with European settlers. The study estimated that the removal of the bison caused a decrease of as much as 2.2 million tons per year. Another study examined the change in the methane concentration in the atmosphere at the end of the Pleistocene epoch after the extinction of megafauna in the Americas. After early humans migrated to the Americas about 13,000 BP, their hunting and other associated ecological impacts led to the extinction of many megafaunal species there. Calculations suggest that this extinction decreased methane production by about 9.6 million tons per year. This suggests that the absence of megafaunal methane emissions may have contributed to the abrupt climatic cooling at the onset of the Younger Dryas. The decrease in atmospheric methane that occurred at that time, as recorded in ice cores, was 2–4 times more rapid than any other decrease in the last half million years, suggesting that an unusual mechanism was at work.

Disease

The hyperdisease hypothesis, proposed by Ross MacPhee in 1997, states that the megafaunal die-off was due to an indirect transmission of diseases by newly arriving humans. According to MacPhee, aboriginals or animals travelling with them, such as domestic dogs or livestock, introduced one or more highly virulent diseases into new environments whose native population had no immunity to them, eventually leading to their extinction. K-selection animals, such as the now-extinct megafauna, are especially vulnerable to diseases, as opposed to r-selection animals who have a shorter gestation period and a higher population size. Humans are thought to be the sole cause as other earlier migrations of animals into North America from Eurasia did not cause extinctions. A related theory proposes that a highly contagious prion disease similar to chronic wasting disease or scrapie that was capable of infecting a large number of species was the culprit. Animals weakened by this "superprion" would also have easily become reservoirs of viral and bacterial diseases as they succumbed to neurological degeneration from the prion, causing a cascade of different diseases to spread among various mammal species. This theory could potentially explain the prevalence of heterozygosity at codon 129 of the prion protein gene in humans, which has been speculated to be the result of natural selection against homozygous genotypes that were more susceptible to prion disease and thus potentially a tell-tale of a major prion pandemic that affected humans of or younger than reproductive age far in the past and disproportionately killed before they could reproduce those with homozygous genotypes at codon 129.

There are many problems with this theory, as this disease would have to meet several criteria: it has to be able to sustain itself in an environment with few hosts; it has to have a high infection rate; and be extremely lethal, with a mortality rate of 50–75%. Disease has to be very virulent to kill off all the individuals in a species, and even such a virulent disease as West Nile fever is unlikely to have caused extinction. However, diseases have been the cause for some extinctions. The introduction of avian malaria and avipoxvirus, for example, has greatly decreased the populations of the endemic birds of Hawaii, with some going extinct

Contemporary extinction

History

Contemporary human overpopulation and continued population growth, along with per-capita consumption growth, prominently in the past two centuries, are regarded as the underlying causes of extinction. Inger Andersen, the executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, stated that "we need to understand that the more people there are, the more we put the Earth under heavy pressure. As far as biodiversity is concerned, we are at war with nature."

Some scholars assert that the emergence of capitalism as the dominant economic system has accelerated ecological exploitation and destruction, and has also exacerbated mass species extinction. CUNY professor David Harvey, for example, posits that the neoliberal era "happens to be the era of the fastest mass extinction of species in the Earth's recent history". Major lobbying organizations representing corporations in the agriculture, fisheries, forestry and paper, mining, and oil and gas industries, including the United States Chamber of Commerce, have been pushing back against legislation that could address the extinction crisis. A 2022 report by the climate think tank InfluenceMap stated that "although industry associations, especially in the US, appear reluctant to discuss the biodiversity crisis, they are clearly engaged on a wide range of policies with significant impacts on biodiversity loss."

The loss of animal species from ecological communities, defaunation, is primarily driven by human activity. This has resulted in empty forests, ecological communities depleted of large vertebrates. This is not to be confused with extinction, as it includes both the disappearance of species and declines in abundance. Defaunation effects were first implied at the Symposium of Plant-Animal Interactions at the University of Campinas, Brazil in 1988 in the context of Neotropical forests. Since then, the term has gained broader usage in conservation biology as a global phenomenon.

Big cat populations have severely declined over the last half-century and could face extinction in the following decades. According to 2011 IUCN estimates: lions are down to 25,000, from 450,000; leopards are down to 50,000, from 750,000; cheetahs are down to 12,000, from 45,000; tigers are down to 3,000 in the wild, from 50,000. A December 2016 study by the Zoological Society of London, Panthera Corporation and Wildlife Conservation Society showed that cheetahs are far closer to extinction than previously thought, with only 7,100 remaining in the wild, existing within only 9% of their historic range. Human pressures are to blame for the cheetah population crash, including prey loss due to overhunting by people, retaliatory killing from farmers, habitat loss and the illegal wildlife trade.

We are seeing the effects of 7 billion people on the planet. At present rates, we will lose the big cats in 10 to 15 years.

— Naturalist Dereck Joubert, co-founder of the National Geographic Big Cats Initiative

The term pollinator decline refers to the reduction in abundance of insect and other animal pollinators in many ecosystems worldwide beginning at the end of the twentieth century, and continuing into the present day. Pollinators, which are necessary for 75% of food crops, are declining globally in both abundance and diversity. A 2017 study led by Radboud University's Hans de Kroon indicated that the biomass of insect life in Germany had declined by three-quarters in the previous 25 years. Participating researcher Dave Goulson of Sussex University stated that their study suggested that humans are making large parts of the planet uninhabitable for wildlife. Goulson characterized the situation as an approaching "ecological Armageddon", adding that "if we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse." A 2019 study found that over 40% of insect species are threatened with extinction. The most significant drivers in the decline of insect populations are associated with intensive farming practices, along with pesticide use and climate change. The world's insect population decreases by around 1 to 2 per cent per year.

We have driven the rate of biological extinction, the permanent loss of species, up several hundred times beyond its historical levels, and are threatened with the loss of a majority of all species by the end of the 21st century.

— Peter Raven, former president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), in the foreword to their publication AAAS Atlas of Population and Environment

Various species are predicted to become extinct in the near future, among them some species of rhinoceros, primates and pangolins. Others, including several species of giraffe, are considered "vulnerable" and are experiencing significant population declines from anthropogenic impacts including hunting, deforestation and conflict. Hunting alone threatens bird and mammalian populations around the world. The direct killing of megafauna for meat and body parts is the primary driver of their destruction, with 70% of the 362 megafauna species in decline as of 2019. Mammals in particular have suffered such severe losses as the result of human activity that it could take several million years for them to recover. Contemporary assessments have discovered that roughly 41% of amphibians, 25% of mammals, 21% of reptiles and 14% of birds are threatened with extinction, which could disrupt ecosystems on a global scale and eliminate billions of years of phylogenetic diversity. 189 countries, which are signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Rio Accord), have committed to preparing a Biodiversity Action Plan, a first step at identifying specific endangered species and habitats, country by country.

For the first time since the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, we face a global mass extinction of wildlife. We ignore the decline of other species at our peril – for they are the barometer that reveals our impact on the world that sustains us.

— Mike Barrett, director of science and policy at WWF's UK branch

A 2023 study published in Current Biology concluded that current biodiversity loss rates could reach a tipping point and inevitably trigger a total ecosystem collapse.

Recent extinction

Recent extinctions are more directly attributable to human influences, whereas prehistoric extinctions can be attributed to other factors, such as global climate change. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) characterises 'recent' extinction as those that have occurred past the cut-off point of 1500, and at least 875 plant and animal species have gone extinct since that time and 2009. Some species, such as the Père David's deer and the Hawaiian crow, are extinct in the wild, and survive solely in captive populations. Other populations are only locally extinct (extirpated), still existent elsewhere, but reduced in distribution, as with the extinction of gray whales in the Atlantic, and of the leatherback sea turtle in Malaysia.

Humans are rapidly driving the largest vertebrate animals towards extinction, and in the process interrupting a 66-million-year-old feature of ecosystems, the relationship between diet and body mass, which researchers suggest could have unpredictable consequences. A 2019 study published in Nature Communications found that rapid biodiversity loss is impacting larger mammals and birds to a much greater extent than smaller ones, with the body mass of such animals expected to shrink by 25% over the next century. Another 2019 study published in Biology Letters found that extinction rates are perhaps much higher than previously estimated, in particular for bird species.

The 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services lists the primary causes of contemporary extinctions in descending order: (1) changes in land and sea use (primarily agriculture and overfishing respectively); (2) direct exploitation of organisms such as hunting; (3) anthropogenic climate change; (4) pollution and (5) invasive alien species spread by human trade. This report, along with the 2020 Living Planet Report by the WWF, both project that climate change will be the leading cause in the next several decades.

A June 2020 study published in PNAS posits that the contemporary extinction crisis "may be the most serious environmental threat to the persistence of civilization, because it is irreversible" and that its acceleration "is certain because of the still fast growth in human numbers and consumption rates." The study found that more than 500 vertebrate species are poised to be lost in the next two decades.

Habitat destruction

Humans both create and destroy crop cultivar and domesticated animal varieties. Advances in transportation and industrial farming has led to monoculture and the extinction of many cultivars. The use of certain plants and animals for food has also resulted in their extinction, including silphium and the passenger pigeon. It was estimated in 2012 that 13 percent of Earth's ice-free land surface is used as row-crop agricultural sites, 26 percent used as pastures, and 4 percent urban-industrial areas.

In March 2019, Nature Climate Change published a study by ecologists from Yale University, who found that over the next half century, human land use will reduce the habitats of 1,700 species by up to 50%, pushing them closer to extinction. That same month PLOS Biology published a similar study drawing on work at the University of Queensland, which found that "more than 1,200 species globally face threats to their survival in more than 90% of their habitat and will almost certainly face extinction without conservation intervention".

Since 1970, the populations of migratory freshwater fish have declined by 76%, according to research published by the Zoological Society of London in July 2020. Overall, around one in three freshwater fish species are threatened with extinction due to human-driven habitat degradation and overfishing.

Some scientists and academics assert that industrial agriculture and the growing demand for meat is contributing to significant global biodiversity loss as this is a significant driver of deforestation and habitat destruction; species-rich habitats, such as the Amazon region and Indonesia being converted to agriculture. A 2017 study by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) found that 60% of biodiversity loss can be attributed to the vast scale of feed crop cultivation required to rear tens of billions of farm animals. Moreover, a 2006 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Livestock's Long Shadow, also found that the livestock sector is a "leading player" in biodiversity loss. More recently, in 2019, the IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services attributed much of this ecological destruction to agriculture and fishing, with the meat and dairy industries having a very significant impact. Since the 1970s food production has soared in order to feed a growing human population and bolster economic growth, but at a huge price to the environment and other species. The report says some 25% of the earth's ice-free land is used for cattle grazing. A 2020 study published in Nature Communications warned that human impacts from housing, industrial agriculture and in particular meat consumption are wiping out a combined 50 billion years of earth's evolutionary history (defined as phylogenetic diversity) and driving to extinction some of the "most unique animals on the planet," among them the Aye-aye lemur, the Chinese crocodile lizard and the pangolin. Said lead author Rikki Gumbs:

We know from all the data we have for threatened species, that the biggest threats are agriculture expansion and the global demand for meat. Pasture land, and the clearing of rainforests for production of soy, for me, are the largest drivers – and the direct consumption of animals.

Urbanisation has also been cited as a significant driver of biodiversity loss, particularly of plant life. A 1999 study of local plant extirpations in Great Britain found that urbanisation contributed at least as much to local plant extinction as did agriculture.

Climate change

Climate change is expected to be a major driver of extinctions from the 21st century. Rising levels of carbon dioxide are resulting in influx of this gas into the ocean, increasing its acidity. Marine organisms which possess calcium carbonate shells or exoskeletons experience physiological pressure as the carbonate reacts with acid. For example, this is already resulting in coral bleaching on various coral reefs worldwide, which provide valuable habitat and maintain a high biodiversity. Marine gastropods, bivalves and other invertebrates are also affected, as are the organisms that feed on them. Some studies have suggested that it is not climate change that is driving the current extinction crisis, but the demands of contemporary human civilization on nature. However, a rise in average global temperatures greater than 5.2 °C is projected to cause a mass extinction similar to the "Big Five" mass extinction events of the Phanerozoic, even without other anthropogenic impacts on biodiversity.

Overexploitation

Overhunting can reduce the local population of game animals by more than half, as well as reducing population density, and may lead to extinction for some species. Populations located nearer to villages are significantly more at risk of depletion. Several conservationist organizations, among them IFAW and HSUS, assert that trophy hunters, particularly from the United States, are playing a significant role in the decline of giraffes, which they refer to as a "silent extinction".

The surge in the mass killings by poachers involved in the illegal ivory trade along with habitat loss is threatening African elephant populations. In 1979, their populations stood at 1.7 million; at present there are fewer than 400,000 remaining. Prior to European colonization, scientists believe Africa was home to roughly 20 million elephants. According to the Great Elephant Census, 30% of African elephants (or 144,000 individuals) disappeared over a seven-year period, 2007 to 2014. African elephants could become extinct by 2035 if poaching rates continue.

Fishing has had a devastating effect on marine organism populations for several centuries even before the explosion of destructive and highly effective fishing practices like trawling. Humans are unique among predators in that they regularly prey on other adult apex predators, particularly in marine environments; bluefin tuna, blue whales, North Atlantic right whales and over fifty species of sharks and rays are vulnerable to predation pressure from human fishing, in particular commercial fishing. A 2016 study published in Science concludes that humans tend to hunt larger species, and this could disrupt ocean ecosystems for millions of years. A 2020 study published in Science Advances found that around 18% of marine megafauna, including iconic species such as the Great white shark, are at risk of extinction from human pressures over the next century. In a worst-case scenario, 40% could go extinct over the same time period. According to a 2021 study published in Nature, 71% of oceanic shark and ray populations have been destroyed by overfishing (the primary driver of ocean defaunation) from 1970 to 2018, and are nearing the "point of no return" as 24 of the 31 species are now threatened with extinction, with several being classified as critically endangered. Almost two thirds of sharks and rays around coral reefs are threatened with extinction from overfishing, with 14 of 134 species being critically endangered.

If this pattern goes unchecked, the future oceans would lack many of the largest species in today’s oceans. Many large species play critical roles in ecosystems and so their extinctions could lead to ecological cascades that would influence the structure and function of future ecosystems beyond the simple fact of losing those species.

— Jonathan Payne, associate professor and chair of geological sciences at Stanford University

Disease

The decline of amphibian populations has also been identified as an indicator of environmental degradation. As well as habitat loss, introduced predators and pollution, Chytridiomycosis, a fungal infection accidentally spread by human travel, globalization and the wildlife trade, has caused severe population drops of over 500 amphibian species, and perhaps 90 extinctions, including (among many others) the extinction of the golden toad in Costa Rica, the Gastric-brooding frog in Australia, the Rabb's fringe-limbed treefrog and the extinction of the Panamanian golden frog in the wild. Chytrid fungus has spread across Australia, New Zealand, Central America and Africa, including countries with high amphibian diversity such as cloud forests in Honduras and Madagascar. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans is a similar infection currently threatening salamanders. Amphibians are now the most endangered vertebrate group, having existed for more than 300 million years through three other mass extinctions.

Millions of bats in the US have been dying off since 2012 due to a fungal infection known as white-nose syndrome that spread from European bats, who appear to be immune. Population drops have been as great as 90% within five years, and extinction of at least one bat species is predicted. There is currently no form of treatment, and such declines have been described as "unprecedented" in bat evolutionary history by Alan Hicks of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Between 2007 and 2013, over ten million beehives were abandoned due to colony collapse disorder, which causes worker bees to abandon the queen. Though no single cause has gained widespread acceptance by the scientific community, proposals include infections with Varroa and Acarapis mites; malnutrition; various pathogens; genetic factors; immunodeficiencies; loss of habitat; changing beekeeping practices; or a combination of factors.

By region

Megafauna were once found on every continent of the world, but are now almost exclusively found on the continent of Africa. In some regions, megafauna experienced population crashes and trophic cascades shortly after the earliest human settlers. Worldwide, 178 species of the world's largest mammals died out between 52,000 and 9,000 BC; it has been suggested that a higher proportion of African megafauna survived because they evolved alongside humans. The timing of South American megafaunal extinction appears to precede human arrival, although the possibility that human activity at the time impacted the global climate enough to cause such an extinction has been suggested.

Africa

Africa experienced the smallest decline in megafauna compared to the other continents. This is presumably due to the idea that Afroeurasian megafauna evolved alongside humans, and thus developed a healthy fear of them, unlike the comparatively tame animals of other continents.

Eurasia

Unlike other continents, the megafauna of Eurasia went extinct over a relatively long period of time, possibly due to climate fluctuations fragmenting and decreasing populations, leaving them vulnerable to over-exploitation, as with the steppe bison (Bison priscus). The warming of the arctic region caused the rapid decline of grasslands, which had a negative effect on the grazing megafauna of Eurasia. Most of what once was mammoth steppe was converted to mire, rendering the environment incapable of supporting them, notably the woolly mammoth.

In the western Mediterranean region, anthropogenic forest degradation began around 4,000 BP, during the Chalcolithic, and became especially pronounced during the Roman era. The reasons for the decline of forest ecosystems stem from agriculture, grazing, and mining. During the twilight years of the Western Roman Empire, forests in northwestern Europe rebounded from losses incurred throughout the Roman period, though deforestation on a large scale resumed once again around 800 BP, during the High Middle Ages.

In southern China, human land use is believed to have permanently altered the trend of vegetation dynamics in the region, which was previously governed by temperature. This is evidenced by high fluxes of charcoal from that time interval.

Americas

There has been a debate as to the extent to which the disappearance of megafauna at the end of the last glacial period can be attributed to human activities by hunting, or even by slaughter of prey populations. Discoveries at Monte Verde in South America and at Meadowcroft Rock Shelter in Pennsylvania have caused a controversy regarding the Clovis culture. There likely would have been human settlements prior to the Clovis culture, and the history of humans in the Americas may extend back many thousands of years before the Clovis culture. The amount of correlation between human arrival and megafauna extinction is still being debated: for example, in Wrangel Island in Siberia the extinction of dwarf woolly mammoths (approximately 2000 BCE) did not coincide with the arrival of humans, nor did megafaunal mass extinction on the South American continent, although it has been suggested climate changes induced by anthropogenic effects elsewhere in the world may have contributed.

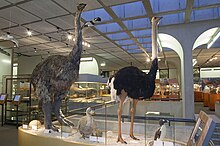

Comparisons are sometimes made between recent extinctions (approximately since the industrial revolution) and the Pleistocene extinction near the end of the last glacial period. The latter is exemplified by the extinction of large herbivores such as the woolly mammoth and the carnivores that preyed on them. Humans of this era actively hunted the mammoth and the mastodon, but it is not known if this hunting was the cause of the subsequent massive ecological changes, widespread extinctions and climate changes.

The ecosystems encountered by the first Americans had not been exposed to human interaction, and may have been far less resilient to human made changes than the ecosystems encountered by industrial era humans. Therefore, the actions of the Clovis people, despite seeming insignificant by today's standards could indeed have had a profound effect on the ecosystems and wild life which was entirely unused to human influence.

In the Yukon, the mammoth steppe ecosystem collapsed between 13,500 and 10,000 BP, though wild horses and woolly mammoths somehow persisted in the region for millennia after this collapse. In what is now Texas, a drop in local plant and animal biodiversity occurred during the Younger Dryas cooling, though while plant diversity recovered after the Younger Dryas, animal diversity did not. In the Channel Islands, multiple terrestrial species went extinct around the same time as human arrival, but direct evidence for an anthropogenic cause of their extinction remains lacking. In the montane forests of the Colombian Andes, spores of coprophilous fungi indicate megafaunal extinction occurred in two waves, the first occurring around 22,900 BP and the second around 10,990 BP. A 2023 study of megafaunal extinctions in the Junín Plateau of Peru found that the timing of the disappearance of megafauna was concurrent with a large uptick in fire activity attributed to human actions, implicating humans as the cause of their local extinction on the plateau.

Australia

Australia was once home to a large assemblage of megafauna, with many parallels to those found on the African continent today. Australia's fauna is characterised by primarily marsupial mammals, and many reptiles and birds, all existing as giant forms until recently. Humans arrived on the continent very early, about 50,000 years ago. The extent human arrival contributed is controversial; climatic drying of Australia 40,000–60,000 years ago was an unlikely cause, as it was less severe in speed or magnitude than previous regional climate change which failed to kill off megafauna. Extinctions in Australia continued from original settlement until today in both plants and animals, whilst many more animals and plants have declined or are endangered.

Due to the older timeframe and the soil chemistry on the continent, very little subfossil preservation evidence exists relative to elsewhere. However, continent-wide extinction of all genera weighing over 100 kilograms, and six of seven genera weighing between 45 and 100 kilograms occurred around 46,400 years ago (4,000 years after human arrival) and the fact that megafauna survived until a later date on the island of Tasmania following the establishment of a land bridge suggest direct hunting or anthropogenic ecosystem disruption such as fire-stick farming as likely causes. The first evidence of direct human predation leading to extinction in Australia was published in 2016.

A 2021 study found that the rate of extinction of Australia's megafauna is rather unusual, with some generalistic species having gone extinct earlier while highly specialised ones having become extinct later or even still surviving today. A mosaic cause of extinction with different anthropogenic and environmental pressures has been proposed.

Caribbean

Human arrival in the Caribbean around 6,000 years ago is correlated with the extinction of many species. These include many different genera of ground and arboreal sloths across all islands. These sloths were generally smaller than those found on the South American continent. Megalocnus were the largest genus at up to 90 kilograms (200 lb), Acratocnus were medium-sized relatives of modern two-toed sloths endemic to Cuba, Imagocnus also of Cuba, Neocnus and many others.

Macaronesia

The arrival of the first human settlers in the Azores saw the introduction of invasive plants and livestock to the archipelago, resulting in the extinction of at least two plant species on Pico Island. On Faial Island, the decline of Prunus lusitanica has been hypothesised by some scholars to have been related to the tree species being endozoochoric, with the extirpation or extinction of various bird species drastically limiting its seed dispersal. Lacustrine ecosystems were ravaged by human colonisation, as evidenced by hydrogen isotopes from C30 fatty acids recording hypoxic bottom waters caused by eutrophication in Lake Funda on Flores Island beginning between 1500 and 1600 AD.

The arrival of humans on the archipelago of Madeira caused the extinction of approximately two-thirds of its endemic bird species, with two non-endemic birds also being locally extirpated from the archipelago. Of thirty-four land snail species collected in a subfossil sample from eastern Madeira Island, nine became extinct following the arrival of humans. On the Desertas Islands, of forty-five land snail species known to exist before human colonisation, eighteen are extinct and five are no longer present on the islands. Eurya stigmosa, whose extinction is typically attributed to climate change following the end of the Pleistocene rather than humans, may have survived until the colonisation of the archipelago by the Portuguese and gone extinct as a result of human activity. Introduced mice have been implicated as a leading driver of extinction on Madeira following its discovery by humans.

In the Canary Islands, native thermophilous woodlands were decimated and two tree taxa were driven extinct following the arrival of its first humans, primarily as a result of increased fire clearance and soil erosion and the introduction of invasive pigs, goats, and rats. Invasive species introductions accelerated during the Age of Discovery when Europeans first settled the Macaronesian archipelago. The archipelago's laurel forests, though still negatively impacted, fared better due to being less suitable for human economic use.

Cabo Verde, like the Canary Islands, witnessed precipitous deforestation upon the arrival of European settlers and various invasive species brought by them in the archipelago, with the archipelago's thermophilous woodlands suffering the greatest destruction. Introduced species, overgrazing, increased fire incidence, and soil degradation have been attributed as the chief causes of Cabo Verde's ecological devastation.

Pacific

Archaeological and paleontological digs on 70 different Pacific islands suggested that numerous species became extinct as people moved across the Pacific, starting 30,000 years ago in the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomon Islands. It is currently estimated that among the bird species of the Pacific, some 2000 species have gone extinct since the arrival of humans, representing a 20% drop in the biodiversity of birds worldwide.

The first human settlers of the Hawaiian islands are thought to have arrived between 300 and 800 CE, with European arrival in the 16th century. Hawaii is notable for its endemism of plants, birds, insects, mollusks and fish; 30% of its organisms are endemic. Many of its species are endangered or have gone extinct, primarily due to accidentally introduced species and livestock grazing. Over 40% of its bird species have gone extinct, and it is the location of 75% of extinctions in the United States. Extinction has increased in Hawaii over the last 200 years and is relatively well documented, with extinctions among native snails used as estimates for global extinction rates.

Madagascar

Within 500 years of the arrival of humans between 2,500 and 2,000 years ago, nearly all of Madagascar's distinct, endemic and geographically isolated megafauna became extinct. The largest animals, of more than 150 kilograms (330 lb), were extinct very shortly after the first human arrival, with large and medium-sized species dying out after prolonged hunting pressure from an expanding human population moving into more remote regions of the island around 1000 years ago. The eight or more species of elephant birds, giant flightless ratites in the genera Aepyornis, Vorombe, and Mullerornis, are extinct from over-hunting, as well as 17 species of lemur, known as giant, subfossil lemurs. Some of these lemurs typically weighed over 150 kilograms (330 lb), and their fossils have provided evidence of human butchery on many species. Smaller fauna experienced initial increases due to decreased competition, and then subsequent declines over the last 500 years. All fauna weighing over 10 kilograms (22 lb) died out. The primary reasons for the decline of Madagascar's biota, which at the time was already stressed by natural aridification, were human hunting, herding, farming, and forest clearing, all of which persist and threaten Madagascar's remaining taxa today. The natural ecosystems of Madagascar as a whole were further impacted by the much greater incidence of fire as a result of anthropogenic fire production; evidence from Lake Amparihibe on the island of Nosy Be indicates a shift in local vegetation from intact rainforest to a fire-disturbed patchwork of grassland and woodland between 1300 and 1000 BP.

New Zealand

New Zealand is characterised by its geographic isolation and island biogeography, and had been isolated from mainland Australia for 80 million years. It was the last large land mass to be colonised by humans. The arrival of Polynesian settlers circa 12th century resulted in the extinction of all of the islands' megafaunal birds within several hundred years. The moa, large flightless ratites, became extinct within 200 years of the arrival of human settlers. The Polynesians also introduced the Polynesian rat. This may have put some pressure on other birds but at the time of early European contact (18th century) and colonisation (19th century) the bird life was prolific. With them, the Europeans brought various invasive species including ship rats, possums, cats and mustelids which devastated native bird life, some of which had adapted flightlessness and ground nesting habits, and had no defensive behavior as a result of having no native mammalian predators. The kakapo, the world's biggest parrot, which is flightless, now only exists in managed breeding sanctuaries. New Zealand's national emblem, the kiwi, is on the endangered bird list.

Mitigation

Stabilizing human populations, reining in capitalism and decreasing economic demands and shifting them to economic activities with low impacts on biodiversity, transitioning to plant-based diets, and increasing the number and size of terrestrial and marine protected areas are the keys to avoiding or limiting biodiversity loss and a possible sixth mass extinction. Rodolfo Dirzo and Paul R. Ehrlich suggest that "the one fundamental, necessary, 'simple' cure, ... is reducing the scale of the human enterprise." According to a 2021 paper published in Frontiers in Conservation Science, humanity almost certainly faces a "ghastly future" of mass extinction, biodiversity collapse, climate change and their impacts unless major efforts to change human industry and activity are rapidly undertaken.

Reducing human population growth has been suggested as a means of mitigating climate change and the biodiversity crisis, although many scholars believe it has been largely ignored in mainstream policy discourse. An alternative proposal is greater agricultural efficiency & sustainability. Lots of non-arable land can be made into arable land good for growing food crops. Mushrooms have also been known to repair damaged soil.

A 2018 article in Science advocated for the global community to designate 30 percent of the planet by 2030, and 50 percent by 2050, as protected areas in order to mitigate the contemporary extinction crisis. It highlighted that the human population is projected to grow to 10 billion by the middle of the century, and consumption of food and water resources is projected to double by this time. A 2022 report published in Science warned that 44% of earth's terrestrial surface, or 64 million square kilometres (24.7 million square miles), must be conserved and made "ecologically sound" in order to prevent further biodiversity loss.

In November 2018, the UN's biodiversity chief Cristiana Pașca Palmer urged people around the world to put pressure on governments to implement significant protections for wildlife by 2020. She called biodiversity loss a "silent killer" as dangerous as global warming, but said it had received little attention by comparison. "It’s different from climate change, where people feel the impact in everyday life. With biodiversity, it is not so clear but by the time you feel what is happening, it may be too late." In January 2020, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity drafted a Paris-style plan to stop biodiversity and ecosystem collapse by setting the deadline of 2030 to protect 30% of the earth's land and oceans and to reduce pollution by 50%, with the goal of allowing for the restoration of ecosystems by 2050. The world failed to meet the Aichi Biodiversity targets for 2020 set by the convention during a summit in Japan in 2010. Of the 20 biodiversity targets proposed, only six were "partially achieved" by the deadline. It was called a global failure by Inger Andersen, head of the United Nations Environment Programme:

"From COVID-19 to massive wildfires, floods, melting glaciers and unprecedented heat, our failure to meet the Aichi (biodiversity) targets — protect our our home — has very real consequences. We can no longer afford to cast nature to the side."

Some scientists have proposed keeping extinctions below 20 per year for the next century as a global target to reduce species loss, which is the biodiversity equivalent of the 2 °C climate target, although it is still much higher than the normal background rate of two per year prior to anthropogenic impacts on the natural world.

An October 2020 report on the "era of pandemics" from IPBES found that many of the same human activities that contribute to biodiversity loss and climate change, including deforestation and the wildlife trade, have also increased the risk of future pandemics. The report offers several policy options to reduce such risk, such as taxing meat production and consumption, cracking down on the illegal wildlife trade, removing high disease-risk species from the legal wildlife trade, and eliminating subsidies to businesses which are harmful to the environment. According to marine zoologist John Spicer, "the COVID-19 crisis is not just another crisis alongside the biodiversity crisis and the climate change crisis. Make no mistake, this is one big crisis – the greatest that humans have ever faced."

In December 2022, nearly every country on earth, with the United States and the Holy See being the only exceptions, signed onto the agreement formulated at the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP 15) which includes protecting 30% of land and oceans by 2030 and 22 other targets intended to mitigate the extinction crisis. The agreement is weaker than the Aichi Targets of 2010. It was criticized by some countries for being rushed and not going far enough to protect endangered species.