Keratin (/ˈkɛrətɪn/) is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as scleroproteins. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, horns, claws, hooves, and the outer layer of skin among vertebrates. Keratin also protects epithelial cells from damage or stress. Keratin is extremely insoluble in water and organic solvents. Keratin monomers assemble into bundles to form intermediate filaments, which are tough and form strong unmineralized epidermal appendages found in reptiles, birds, amphibians, and mammals. Excessive keratinization participate in fortification of certain tissues such as in horns of cattle and rhinos, and armadillos' osteoderm. The only other biological matter known to approximate the toughness of keratinized tissue is chitin. Keratin comes in two types, the primitive, softer forms found in all vertebrates and harder, derived forms found only among sauropsids (reptiles and birds).

Spider silk is classified as keratin, although production of the protein may have evolved independently of the process in vertebrates.

Examples of occurrence

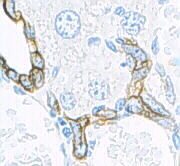

Alpha-keratins (α-keratins) are found in all vertebrates. They form the hair (including wool), the outer layer of skin, horns, nails, claws and hooves of mammals, and the slime threads of hagfish. The baleen plates of filter-feeding whales are also made of keratin. Keratin filaments are abundant in keratinocytes in the hornified layer of the epidermis; these are proteins which have undergone keratinization. They are also present in epithelial cells in general. For example, mouse thymic epithelial cells react with antibodies for keratin 5, keratin 8, and keratin 14. These antibodies are used as fluorescent markers to distinguish subsets of mouse thymic epithelial cells in genetic studies of the thymus.

The harder beta-keratins (β-keratins) are found only in the sauropsids, that is all living reptiles and birds. They are found in the nails, scales, and claws of reptiles, in some reptile shells (Testudines, such as tortoise, turtle, terrapin), and in the feathers, beaks, and claws of birds. These keratins are formed primarily in beta sheets. However, beta sheets are also found in α-keratins. Recent scholarship has shown that sauropsid β-keratins are fundamentally different from α-keratins at a genetic and structural level. The new term corneous beta protein (CBP) has been proposed to avoid confusion with α-keratins.

Keratins (also described as cytokeratins) are polymers of type I and type II intermediate filaments that have been found only in chordates (vertebrates, amphioxi, urochordates). Nematodes and many other non-chordate animals seem to have only type VI intermediate filaments, fibers that structure the nucleus.

Genes

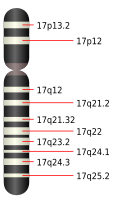

The human genome encodes 54 functional keratin genes, located in two clusters on chromosomes 12 and 17. This suggests that they originated from a series of gene duplications on these chromosomes.

The keratins include the following proteins of which KRT23, KRT24, KRT25, KRT26, KRT27, KRT28, KRT31, KRT32, KRT33A, KRT33B, KRT34, KRT35, KRT36, KRT37, KRT38, KRT39, KRT40, KRT71, KRT72, KRT73, KRT74, KRT75, KRT76, KRT77, KRT78, KRT79, KRT8, KRT80, KRT81, KRT82, KRT83, KRT84, KRT85 and KRT86 have been used to describe keratins past 20.

Protein structure

The first sequences of keratins were determined by Israel Hanukoglu and Elaine Fuchs (1982, 1983). These sequences revealed that there are two distinct but homologous keratin families, which were named type I and type II keratins. By analysis of the primary structures of these keratins and other intermediate filament proteins, Hanukoglu and Fuchs suggested a model in which keratins and intermediate filament proteins contain a central ~310 residue domain with four segments in α-helical conformation that are separated by three short linker segments predicted to be in beta-turn conformation. This model has been confirmed by the determination of the crystal structure of a helical domain of keratins.

Type 1 and 2 Keratins

The human genome has 54 functional annotated Keratin genes, 28 are in the Keratin type 1 family, and 26 are in the Keratin type 2 family.

Fibrous keratin molecules supercoil to form a very stable, left-handed superhelical motif to multimerise, forming filaments consisting of multiple copies of the keratin monomer.

The major force that keeps the coiled-coil structure is hydrophobic interactions between apolar residues along the keratins helical segments.

Limited interior space is the reason why the triple helix of the (unrelated) structural protein collagen, found in skin, cartilage and bone, likewise has a high percentage of glycine. The connective tissue protein elastin also has a high percentage of both glycine and alanine. Silk fibroin, considered a β-keratin, can have these two as 75–80% of the total, with 10–15% serine, with the rest having bulky side groups. The chains are antiparallel, with an alternating C → N orientation. A preponderance of amino acids with small, nonreactive side groups is characteristic of structural proteins, for which H-bonded close packing is more important than chemical specificity.

Disulfide bridges

In addition to intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, the distinguishing feature of keratins is the presence of large amounts of the sulfur-containing amino acid cysteine, required for the disulfide bridges that confer additional strength and rigidity by permanent, thermally stable crosslinking—in much the same way that non-protein sulfur bridges stabilize vulcanized rubber. Human hair is approximately 14% cysteine. The pungent smells of burning hair and skin are due to the volatile sulfur compounds formed. Extensive disulfide bonding contributes to the insolubility of keratins, except in a small number of solvents such as dissociating or reducing agents.

The more flexible and elastic keratins of hair have fewer interchain disulfide bridges than the keratins in mammalian fingernails, hooves and claws (homologous structures), which are harder and more like their analogs in other vertebrate classes. Hair and other α-keratins consist of α-helically coiled single protein strands (with regular intra-chain H-bonding), which are then further twisted into superhelical ropes that may be further coiled. The β-keratins of reptiles and birds have β-pleated sheets twisted together, then stabilized and hardened by disulfide bridges.

Thiolated polymers (=thiomers) can form disulfide bridges with cysteine substructures of keratins getting covalently attached to these proteins. Thiomers exhibit therefore high binding properties to keratins found in hair, on skin and on the surface of many cell types.

Filament formation

It has been proposed that keratins can be divided into 'hard' and 'soft' forms, or 'cytokeratins' and 'other keratins'. That model is now understood to be correct. A new nuclear addition in 2006 to describe keratins takes this into account.

Keratin filaments are intermediate filaments. Like all intermediate filaments, keratin proteins form filamentous polymers in a series of assembly steps beginning with dimerization; dimers assemble into tetramers and octamers and eventually, if the current hypothesis holds, into unit-length-filaments (ULF) capable of annealing end-to-end into long filaments.

Pairing

| A (neutral-basic) | B (acidic) | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| keratin 1, keratin 2 | keratin 9, keratin 10 | stratum corneum, keratinocytes |

| keratin 3 | keratin 12 | cornea |

| keratin 4 | keratin 13 | stratified epithelium |

| keratin 5 | keratin 14, keratin 15 | stratified epithelium |

| keratin 6 | keratin 16, keratin 17 | squamous epithelium |

| keratin 7 | keratin 19 | ductal epithelia |

| keratin 8 | keratin 18, keratin 20 | simple epithelium |

Cornification

Cornification is the process of forming an epidermal barrier in stratified squamous epithelial tissue. At the cellular level, cornification is characterised by:

- production of keratin

- production of small proline-rich (SPRR) proteins and transglutaminase which eventually form a cornified cell envelope beneath the plasma membrane

- terminal differentiation

- loss of nuclei and organelles, in the final stages of cornification

Metabolism ceases, and the cells are almost completely filled by keratin. During the process of epithelial differentiation, cells become cornified as keratin protein is incorporated into longer keratin intermediate filaments. Eventually the nucleus and cytoplasmic organelles disappear, metabolism ceases and cells undergo a programmed death as they become fully keratinized. In many other cell types, such as cells of the dermis, keratin filaments and other intermediate filaments function as part of the cytoskeleton to mechanically stabilize the cell against physical stress. It does this through connections to desmosomes, cell–cell junctional plaques, and hemidesmosomes, cell-basement membrane adhesive structures.

Cells in the epidermis contain a structural matrix of keratin, which makes this outermost layer of the skin almost waterproof, and along with collagen and elastin gives skin its strength. Rubbing and pressure cause thickening of the outer, cornified layer of the epidermis and form protective calluses, which are useful for athletes and on the fingertips of musicians who play stringed instruments. Keratinized epidermal cells are constantly shed and replaced.

These hard, integumentary structures are formed by intercellular cementing of fibers formed from the dead, cornified cells generated by specialized beds deep within the skin. Hair grows continuously and feathers molt and regenerate. The constituent proteins may be phylogenetically homologous but differ somewhat in chemical structure and supermolecular organization. The evolutionary relationships are complex and only partially known. Multiple genes have been identified for the β-keratins in feathers, and this is probably characteristic of all keratins.

Silk

The silk fibroins produced by insects and spiders are often classified as keratins, though it is unclear whether they are phylogenetically related to vertebrate keratins.

Silk found in insect pupae, and in spider webs and egg casings, also has twisted β-pleated sheets incorporated into fibers wound into larger supermolecular aggregates. The structure of the spinnerets on spiders' tails, and the contributions of their interior glands, provide remarkable control of fast extrusion. Spider silk is typically about 1 to 2 micrometers (μm) thick, compared with about 60 μm for human hair, and more for some mammals. The biologically and commercially useful properties of silk fibers depend on the organization of multiple adjacent protein chains into hard, crystalline regions of varying size, alternating with flexible, amorphous regions where the chains are randomly coiled. A somewhat analogous situation occurs with synthetic polymers such as nylon, developed as a silk substitute. Silk from the hornet cocoon contains doublets about 10 μm across, with cores and coating, and may be arranged in up to 10 layers, also in plaques of variable shape. Adult hornets also use silk as a glue, as do spiders.

Glue

Glues made from partially-hydrolysed keratin include hoof glue and horn glue.

Clinical significance

Abnormal growth of keratin can occur in a variety of conditions including keratosis, hyperkeratosis and keratoderma.

Mutations in keratin gene expression can lead to, among others:

- Alopecia areata

- Epidermolysis bullosa simplex

- Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens

- Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis

- Steatocystoma multiplex

- Keratosis pharyngis

- Rhabdoid cell formation in large cell lung carcinoma with rhabdoid phenotype

Several diseases, such as athlete's foot and ringworm, are caused by infectious fungi that feed on keratin.

Keratin is highly resistant to digestive acids if ingested. Cats regularly ingest hair as part of their grooming behavior, leading to the gradual formation of hairballs that may be expelled orally or excreted. In humans, trichophagia may lead to Rapunzel syndrome, an extremely rare but potentially fatal intestinal condition.