| Cognitive rehabilitation therapy | |

|---|---|

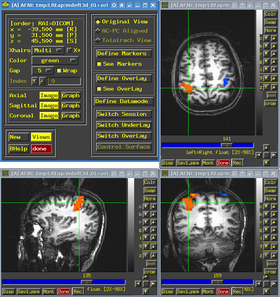

Effects of cognitive rehabilitation therapy, assessed using fMRI. |

Cognitive rehabilitation refers to a wide range of evidence-based interventions designed to improve cognitive functioning in brain-injured or otherwise cognitively impaired individuals to restore normal functioning, or to compensate for cognitive deficits. It entails an individualized program of specific skills training and practice plus metacognitive strategies. Metacognitive strategies include helping the patient increase self-awareness regarding problem-solving skills by learning how to monitor the effectiveness of these skills and self-correct when necessary.

Cognitive rehabilitation therapy (offered by a trained therapist) is a subset of Cognitive Rehabilitation (community-based rehabilitation, often in traumatic brain injury; provided by rehabilitation professionals) and has been shown to be effective for individuals who had a stroke in the left or right hemisphere. or brain trauma. A computer-assisted type of cognitive rehabilitation therapy called cognitive remediation therapy has been used to treat schizophrenia, ADHD, and major depressive disorder.

Cognitive rehabilitation builds upon brain injury strategies involving memory, executive functions, activities planning and "follow through" (e.g., memory, task sequencing, lists).

It may also be recommended for traumatic brain injury, the primary population for which it was developed in the university medical and rehabilitation communities, such as that sustained by U.S. Representative Gabby Giffords, according to Dr. Gregory J. O'Shanick of the Brain Injury Association of America. Her new doctor has confirmed that it will be part of her rehabilitation. Cognitive rehabilitation may be part of a comprehensive community services program and integrated into residential services, such as supported living, supported employment, family support, professional education, home health (as personal assistance), recreation, or education programs in the community.

Cognitive rehabilitation for spatial neglect following stroke

The current body of evidence is uncertain on the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation for reducing the disabling effects of neglect and increasing independence remains unproven. However, there is limited evidence that cognitive rehabilitation may have an immediate beneficial effect on tests of neglect. Overall, no rehabilitation approach can be supported by evidence for spatial neglect.

Assessments

According to the standard text by Sohlberg and Mateer:

Individuals and families respond differently to different interventions, in different ways, at different times after injury. Premorbid functioning, personality, social support, and environmental demands are but a few of the factors that can profoundly influence outcome. In this variable response to treatment, cognitive rehabilitation is no different from treatment for cancer, diabetes, heart disease, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injury, psychiatric disorders, or any other injury or disease process for which variable response to different treatments is the norm.

Nevertheless, many different statistical analyses of the benefits of this therapy have been carried out. One study made in 2002 analyzed 47 treatment comparisons and reported "a differential benefit in favor of cognitive rehabilitation in 37 of 47 (78.7%) comparisons, with no comparison demonstrating a benefit in favor of the alternative treatment condition."

An internal study conducted by the Tricare Management Agency in 2009 is cited by the US Department of Defense as its reason for refusing to pay for this therapy for veterans who have had traumatic brain injury. According to Tricare, "There is insufficient, evidence-based research available to conclude that cognitive rehabilitation therapy is beneficial in treating traumatic brain injury." The ECRI Institute, whose report serves as the basis for this decision by the Department of Defense, has summed up their own findings this way:

Citing this 2009 assessment, US Department of Defense, one of the federal agencies not responsible for health care decisions in the US, has declared that cognitive rehabilitation therapy is scientifically unproved and should refer their concerns to the US Department of Health and Human Services, US Budget and Management, and/or the Government Accountability Office (GAO). As a result, it refuses to cover the cost of cognitive rehabilitation for brain-injured veterans. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness studies, together with an analysis of personnel and veterans' services for new our emerging groups in head and brain injuries, are recommended.In our report, we carried out several meta-analyses using data from 18 randomized controlled trials. Based on data from these studies, we were able to conclude the following:

- Adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury who receive social skills training perform significantly better on measures of social communication than patients who receive no treatment.

- Adults with traumatic brain injury who receive comprehensive cognitive rehabilitation therapy report significant improvement on measures of quality of life compared to patients who receive a less intense form of therapy.

The strength of the evidence supporting our conclusions was low due to the small number of studies that addressed the outcomes of interest. Further, the evidence was too weak to draw any definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation therapy for treating deficits related to the following cognitive areas: attention, memory, visuospacial skills, and executive function. The following factors contributed to the weakness of the evidence: differences in the outcomes assessed in the studies, differences in the types of cognitive rehabilitation therapy methods/strategies employed across studies, differences in the control conditions, and/or insufficient number of studies addressing an outcome.