From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Galileo Galilei Simon Marius |

||||||||

| Discovery date | 8 January 1610[1] | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| Jupiter II | |||||||||

| Adjectives | Europan | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[3] | |||||||||

| Epoch 8 January 2004 | |||||||||

| Periapsis | 664862 km[a] | ||||||||

| Apoapsis | 676938 km[b] | ||||||||

Mean orbit radius

|

670900 km[2] | ||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.009[2] | ||||||||

| 3.551181 d[2] | |||||||||

Average orbital speed

|

13.740 km/s[2] | ||||||||

| Inclination | 0.470° (to Jupiter's equator)[2] | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Jupiter | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

Mean radius

|

1560.8±0.5 km (0.245 Earths)[4] | ||||||||

| 3.09×107 km2 (0.061 Earths)[c] | |||||||||

| Volume | 1.593×1010 km3 (0.015 Earths)[d] | ||||||||

| Mass | (4.799844±0.000013)×1022 kg (0.008 Earths)[4] | ||||||||

Mean density

|

3.013±0.005 g/cm3[4] | ||||||||

| 1.314 m/s2 (0.134 g)[e] | |||||||||

| 2.025 km/s[f] | |||||||||

| Synchronous[5] | |||||||||

| 0.1°[6] | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.67 ± 0.03[4] | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| 5.29 (opposition)[4] | |||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||

Surface pressure

|

0.1 µPa (10−12 bar)[8] | ||||||||

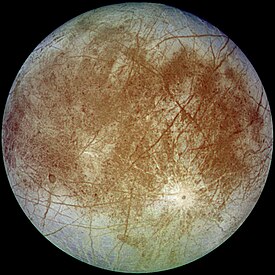

Europa

Slightly smaller than the Moon, Europa is primarily made of silicate rock and has a water-ice crust and probably an iron–nickel core. It has a tenuous atmosphere composed primarily of oxygen. Its surface is striated by cracks and streaks, whereas craters are relatively rare. It has the smoothest surface of any known solid object in the Solar System.[10] The apparent youth and smoothness of the surface have led to the hypothesis that a water ocean exists beneath it, which could conceivably serve as an abode for extraterrestrial life.[11] This hypothesis proposes that heat from tidal flexing causes the ocean to remain liquid and drives geological activity similar to plate tectonics.[12] On 8 September 2014, NASA reported finding evidence confirming earlier reports of plate tectonics in Europa's thick ice shell – the first sign of such geological activity on a world other than Earth.[13]

In December 2013, NASA reported the detection of "clay-like minerals" (specifically, phyllosilicates), often associated with "organic material" on the icy crust of Europa.[14] In addition, NASA announced, based on studies with the Hubble Space Telescope, that water vapor plumes were detected on Europa and were similar to water vapor plumes detected on Enceladus, moon of Saturn.[15]

The Galileo mission, launched in 1989, provided the bulk of current data on Europa. No spacecraft has yet landed on Europa, but its intriguing characteristics have led to several ambitious exploration proposals. The European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) is a mission to Europa that is due to launch in 2022.[16] NASA is planning a robotic mission that would be launched in the "mid-2020s".[17]

Discovery and naming

Europa, along with Jupiter's three other large moons, Io, Ganymede, and Callisto, was discovered by Galileo Galilei on 8 January 1610,[1] and possibly independently by Simon Marius. The first reported observation of Io and Europa was made by Galileo Galilei on 7 January 1610 using a 20×-magnification refracting telescope at the University of Padua. However, in that observation, Galileo could not separate Io and Europa due to the low magnification of his telescope, so that the two were recorded as a single point of light. Io and Europa were seen for the first time as separate bodies during Galileo's observations of the Jupiter system the following day, 8 January 1610 (used as the discovery date for Europa by the IAU).[1] It is named after a Phoenician noblewoman in Greek mythology, Europa, who was courted by Zeus and became the queen of Crete.[18]Like all the Galilean satellites, Europa is named after a lover of Zeus, the Greek counterpart of Jupiter, in this case Europa, daughter of the king of Tyre. The naming scheme was suggested by Simon Marius, who apparently discovered the four satellites independently, though Galileo accused Marius of plagiarism.[19][20] Marius attributed the proposal to Johannes Kepler.[19][20]

The names fell out of favor for a considerable time and were not revived in general use until the mid-20th century.[21] In much of the earlier astronomical literature, Europa is simply referred to by its Roman numeral designation as Jupiter II (a system also introduced by Galileo) or as the "second satellite of Jupiter". In 1892, the discovery of Amalthea, whose orbit lay closer to Jupiter than those of the Galilean moons, pushed Europa to the third position. The Voyager probes discovered three more inner satellites in 1979, so Europa is now considered Jupiter's sixth satellite, though it is still sometimes referred to as Jupiter II.[21]

Orbit and rotation

Europa orbits Jupiter in just over three and a half days, with an orbital radius of about 670,900 km. With an eccentricity of only 0.009, the orbit itself is nearly circular, and the orbital inclination relative to the Jovian equatorial plane is small, at 0.470°.[22] Like its fellow Galilean satellites, Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, with one hemisphere of Europa constantly facing Jupiter. Because of this, there is a sub-Jovian point on Europa's surface, from which Jupiter would appear to hang directly overhead. Europa's prime meridian is the line intersecting this point.[23] Research suggests the tidal locking may not be full, as a non-synchronous rotation has been proposed: Europa spins faster than it orbits, or at least did so in the past. This suggests an asymmetry in internal mass distribution and that a layer of subsurface liquid separates the icy crust from the rocky interior.[5]

The slight eccentricity of Europa's orbit, maintained by the gravitational disturbances from the other Galileans, causes Europa's sub-Jovian point to oscillate about a mean position. As Europa comes slightly nearer to Jupiter, Jupiter's gravitational attraction increases, causing Europa to elongate towards and away from it. As Europa moves slightly away from Jupiter, Jupiter's gravitational force decreases, causing Europa to relax back into a more spherical shape, and creating tides in its ocean. The orbital eccentricity of Europa is continuously pumped by its mean-motion resonance with Io.[24] Thus, the tidal flexing kneads Europa's interior and gives it a source of heat, possibly allowing its ocean to stay liquid while driving subsurface geological processes.[12][24] The ultimate source of this energy is Jupiter's rotation, which is tapped by Io through the tides it raises on Jupiter and is transferred to Europa and Ganymede by the orbital resonance.[24][25]

Scientists analyzing the unique cracks lining the icy face of Europa found evidence showing that this moon of Jupiter likely spun around a tilted axis at some point in time. If this hypothesis is correct, this tilt would be an explanation for many of Europa's features. Europa's immense network of crisscrossing cracks serves as a record of the stresses caused by massive tides in the moon's global ocean. Europa's tilt could influence calculations of how much of the moon's history is recorded in its frozen shell, how much heat is generated by tides in its ocean, and even how long the ocean has been liquid. The moon's ice layer must stretch to accommodate these changes. When there is too much stress, it cracks. A tilt in the moon's axis could suggest that Europa's cracks may be much more recent than previously thought. The reason is that the direction of the spin pole may change by as much as a few degrees per day, completing one precession period over several months. A tilt also could affect the estimates of the age of Europa's ocean. Tidal forces are thought to generate the heat that keeps Europa's ocean liquid, and a tilt in the spin axis might suggest that more heat is generated by tidal forces. This heat might help the ocean to remain liquid longer. Scientists did not specify when the tilt would have occurred and measurements have not been made of the tilt of Europa's axis.[26]

Physical characteristics

Europa is slightly smaller than the Moon. At just over 3,100 kilometres (1,900 mi) in diameter, it is the sixth-largest moon and fifteenth largest object in the Solar System. Though by a wide margin the least massive of the Galilean satellites, it is nonetheless more massive than all known moons in the Solar System smaller than itself combined.[27] Its bulk density suggests that it is similar in composition to the terrestrial planets, being primarily composed of silicate rock.[28]

Internal structure

It is believed that Europa has an outer layer of water around 100 km (62 mi) thick; some as frozen-ice upper crust, some as liquid ocean underneath the ice. Recent magnetic field data from the Galileo orbiter showed that Europa has an induced magnetic field through interaction with Jupiter's, which suggests the presence of a subsurface conductive layer.[29] The layer is likely a salty liquid water ocean. Portions of the crust are estimated to have undergone a rotation of nearly 80°, nearly flipping over (see true polar wander), which would be unlikely if the ice were solidly attached to the mantle.[30] Europa probably contains a metallic iron core.[31]Surface features

Europa is one of the smoothest objects in the Solar System when considering the lack of large scale features such as mountains or craters,[32] however on a smaller scale Europa's equator has been theorised to be covered in 10 metre tall icy spikes called penitentes caused by the effect of direct overhead sunlight on the equator melting vertical cracks.[33] The prominent markings crisscrossing Europa seem to be mainly albedo features, which emphasize low topography. There are few craters on Europa because its surface is tectonically active and young.[34][35] Europa's icy crust gives it an albedo (light reflectivity) of 0.64, one of the highest of all moons.[22][35] This would seem to indicate a young and active surface; based on estimates of the frequency of cometary bombardment that Europa probably endures, the surface is about 20 to 180 million years old.[36] There is currently no full scientific consensus among the sometimes contradictory explanations for the surface features of Europa.[37]

The radiation level at the surface of Europa is equivalent to a dose of about 5400 mSv (540 rem) per day,[38] an amount of radiation that would cause severe illness or death in human beings exposed for a single day.[39]

Lineae

Mosaic of Galileo images showing features indicative of tidal flexing: lineae, lenticulae (domes, pits) and Conamara Chaos.

Europa's most striking surface features are a series of dark streaks crisscrossing the entire globe, called lineae (English: lines). Close examination shows that the edges of Europa's crust on either side of the cracks have moved relative to each other. The larger bands are more than 20 km (12 mi) across, often with dark, diffuse outer edges, regular striations, and a central band of lighter material.[40] The most likely hypothesis states that these lineae may have been produced by a series of eruptions of warm ice as the Europan crust spread open to expose warmer layers beneath.[41] The effect would have been similar to that seen in Earth's oceanic ridges. These various fractures are thought to have been caused in large part by the tidal flexing exerted by Jupiter. Because Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, and therefore always maintains the same approximate orientation towards Jupiter, the stress patterns should form a distinctive and predictable pattern. However, only the youngest of Europa's fractures conform to the predicted pattern; other fractures appear to occur at increasingly different orientations the older they are. This could be explained if Europa's surface rotates slightly faster than its interior, an effect that is possible due to the subsurface ocean mechanically decoupling Europa's surface from its rocky mantle and the effects of Jupiter's gravity tugging on Europa's outer ice crust.[42] Comparisons of Voyager and Galileo spacecraft photos serve to put an upper limit on this hypothetical slippage. The full revolution of the outer rigid shell relative to the interior of Europa occurs over a minimum of 12,000 years.[43] Studies of Voyager and Galileo images have revealed evidence of subduction on Europa's surface, suggesting that, just as the cracks are analogous to ocean ridges,[44][45] so plates of icy crust analogous to tectonic plates on Earth are recycled into the molten interior. Together, the evidence for crustal spreading at bands [44] and convergence at other sites [45] marks the first evidence for plate tectonics on any world other than Earth. [13]

Other geological features

Craggy, 250 m high peaks and smooth plates are jumbled together in a close-up of Conamara Chaos.

Other features present on Europa are circular and elliptical lenticulae (Latin for "freckles"). Many are domes, some are pits and some are smooth, dark spots. Others have a jumbled or rough texture. The dome tops look like pieces of the older plains around them, suggesting that the domes formed when the plains were pushed up from below.[46]

One hypothesis states that these lenticulae were formed by diapirs of warm ice rising up through the colder ice of the outer crust, much like magma chambers in Earth's crust.[46] The smooth, dark spots could be formed by meltwater released when the warm ice breaks through the surface. The rough, jumbled lenticulae (called regions of "chaos"; for example, Conamara Chaos) would then be formed from many small fragments of crust embedded in hummocky, dark material, appearing like icebergs in a frozen sea.[47]

An alternative hypothesis suggest that lenticulae are actually small areas of chaos and that the claimed pits, spots and domes are artefacts resulting from over-interpretation of early, low-resolution Galileo images. The implication is that the ice is too thin to support the convective diapir model of feature formation. [48] [49]

In November 2011, a team of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and elsewhere presented evidence in the journal Nature suggesting that many "chaos terrain" features on Europa sit atop vast lakes of liquid water.[50][51] These lakes would be entirely encased in Europa's icy outer shell and distinct from a liquid ocean thought to exist farther down beneath the ice shell. Full confirmation of the lakes' existence will require a space mission designed to probe the ice shell either physically or indirectly, for example using radar.

Subsurface ocean

Scientists' consensus is that a layer of liquid water exists beneath Europa's surface, and that heat from tidal flexing allows the subsurface ocean to remain liquid.[12][52] Europa's surface temperature averages about 110 K (−160 °C; −260 °F) at the equator and only 50 K (−220 °C; −370 °F) at the poles, keeping Europa's icy crust as hard as granite.[7] The first hints of a subsurface ocean came from theoretical considerations of tidal heating (a consequence of Europa's slightly eccentric orbit and orbital resonance with the other Galilean moons). Galileo imaging team members argue for the existence of a subsurface ocean from analysis of Voyager and Galileo images.[52] The most dramatic example is "chaos terrain", a common feature on Europa's surface that some interpret as a region where the subsurface ocean has melted through the icy crust. This interpretation is extremely controversial. Most geologists who have studied Europa favor what is commonly called the "thick ice" model, in which the ocean has rarely, if ever, directly interacted with the present surface.[53] The different models for the estimation of the ice shell thickness give values between a few kilometers and tens of kilometers.[54] The best evidence for the thick-ice model is a study of Europa's large craters. The largest impact structures are surrounded by concentric rings and appear to be filled with relatively flat, fresh ice; based on this and on the calculated amount of heat generated by Europan tides, it is predicted that the outer crust of solid ice is approximately 10–30 km (6–19 mi) thick, including a ductile "warm ice" layer, which could mean that the liquid ocean underneath may be about 100 km (60 mi) deep.[36][55] This leads to a volume of Europa's oceans of 3 × 1018 m3, slightly more than two times the volume of Earth's oceans.The thin-ice model suggests that Europa's ice shell may be only a few kilometers thick. However, most planetary scientists conclude that this model considers only those topmost layers of Europa's crust that behave elastically when affected by Jupiter's tides. One example is flexure analysis, in which Europa's crust is modeled as a plane or sphere weighted and flexed by a heavy load. Models such as this suggest the outer elastic portion of the ice crust could be as thin as 200 metres (660 ft). If the ice shell of Europa is really only a few kilometers thick, this "thin ice" model would mean that regular contact of the liquid interior with the surface could occur through open ridges, causing the formation of areas of chaotic terrain.[54]

In late 2008, it was suggested Jupiter may keep Europa's oceans warm by generating large planetary tidal waves on Europa because of its small but non-zero obliquity. This previously unconsidered kind of tidal force generates so-called Rossby waves that travel quite slowly, at just a few kilometers per day, but can generate significant kinetic energy. For the current axial tilt estimate of 0.1 degree, the resonance from Rossby waves would store 7.3×1017 J of kinetic energy, which is two thousand times larger than that of the flow excited by the dominant tidal forces.[56][57] Dissipation of this energy could be the principal heat source of Europa's ocean.

The Galileo orbiter found that Europa has a weak magnetic moment, which is induced by the varying part of the Jovian magnetic field. The field strength at the magnetic equator (about 120 nT) created by this magnetic moment is about one-sixth the strength of Ganymede's field and six times the value of Callisto's.[58] The existence of the induced moment requires a layer of a highly electrically conductive material in Europa's interior. The most plausible candidate for this role is a large subsurface ocean of liquid saltwater.[31] Spectrographic evidence suggests that the dark, reddish streaks and features on Europa's surface may be rich in salts such as magnesium sulfate, deposited by evaporating water that emerged from within.[59] Sulfuric acid hydrate is another possible explanation for the contaminant observed spectroscopically.[60] In either case, because these materials are colorless or white when pure, some other material must also be present to account for the reddish color, and sulfur compounds are suspected.[61]

Plumes

Europa may have periodically occurring plumes of water 200 km (120 mi) high, or more than 20 times the height of Mt. Everest.[15][63][64] These plumes appear when Europa is at its farthest point from Jupiter, and are not seen when Europa is at its closest point to Jupiter, in agreement with tidal force modeling predictions.[65] The tidal forces are about 1,000 times stronger than the Moon's effect on Earth. The only other moon in the Solar System exhibiting water vapor plumes is Enceladus.[15] The estimated eruption rate at Europa is about 7000 kg/s[65] compared to about 200 kg/s for the plumes of Enceladus.[66][67]

Atmosphere

Observations with the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph of the Hubble Space Telescope, first described in 1995, revealed that Europa has a thin atmosphere composed mostly of molecular oxygen (O2).[68][69] The surface pressure of Europa's atmosphere is 0.1 μPa, or 10−12 times that of the Earth.[8] In 1997, the Galileo spacecraft confirmed the presence of a tenuous ionosphere (an upper-atmospheric layer of charged particles) around Europa created by solar radiation and energetic particles from Jupiter's magnetosphere,[70][71] providing evidence of an atmosphere.Unlike the oxygen in Earth's atmosphere, Europa's is not of biological origin. The surface-bounded atmosphere forms through radiolysis, the dissociation of molecules through radiation.[72] Solar ultraviolet radiation and charged particles (ions and electrons) from the Jovian magnetospheric environment collide with Europa's icy surface, splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen constituents. These chemical components are then adsorbed and "sputtered" into the atmosphere. The same radiation also creates collisional ejections of these products from the surface, and the balance of these two processes forms an atmosphere.[73] Molecular oxygen is the densest component of the atmosphere because it has a long lifetime; after returning to the surface, it does not stick (freeze) like a water or hydrogen peroxide molecule but rather desorbs from the surface and starts another ballistic arc. Molecular hydrogen never reaches the surface, as it is light enough to escape Europa's surface gravity.[74][75]

Observations of the surface have revealed that some of the molecular oxygen produced by radiolysis is not ejected from the surface. Because the surface may interact with the subsurface ocean (considering the geological discussion above), this molecular oxygen may make its way to the ocean, where it could aid in biological processes.[76] One estimate suggests that, given the turnover rate inferred from the apparent ~0.5 Gyr maximum age of Europa's surface ice, subduction of radiolytically generated oxidizing species might well lead to oceanic free oxygen concentrations that are comparable to those in terrestrial deep oceans.[77]

The molecular hydrogen that escapes Europa's gravity, along with atomic and molecular oxygen, forms a gas torus in the vicinity of Europa's orbit around Jupiter. This "neutral cloud" has been detected by both the Cassini and Galileo spacecraft, and has a greater content (number of atoms and molecules) than the neutral cloud surrounding Jupiter's inner moon Io. Models predict that almost every atom or molecule in Europa's torus is eventually ionized, thus providing a source to Jupiter's magnetospheric plasma. [78]

Exploration

Exploration of Europa began with the Jupiter flybys of Pioneer 10 and 11 in 1973 and 1974 respectively. The first closeup photos were of low resolution compared to later missions.

The two Voyager probes traveled through the Jovian system in 1979 providing more detailed images of Europa's icy surface. The images caused many scientists to speculate about the possibility of a liquid ocean underneath.

Starting in 1995, the Galileo spaceprobe began a Jupiter orbiting mission that lasted for eight years, until 2003, and provided the most detailed examination of the Galilean moons to date. It included the Galileo Europa Mission and Galileo Millennium Mission, with numerous close flybys of Europa.[79]

New Horizons imaged Europa in 2007, as it flew by the Jovian system while on its way to Pluto.

Future missions

Conjectures on extraterrestrial life have ensured a high profile for Europa and have led to steady lobbying for future missions.[80][81] The aims of these missions have ranged from examining Europa's chemical composition to searching for extraterrestrial life in its hypothesized subsurface oceans.[82][83] Robotic missions to Europa need to endure the high radiation environment around itself and Jupiter.[81] Europa receives about 5.40 Sv of radiation per day.[84]In 2011, a Europa mission was recommended by the U.S. Planetary Science Decadal Survey.[85] In response, NASA commissioned Europa lander concept studies in 2011, along with concepts for a Europa flyby (Europa Clipper), and a Europa orbiter.[86][87] The orbiter element option concentrates on the "ocean" science, while the multiple-flyby element (Clipper) concentrates on the chemistry and energy science. On 13 January 2014, the House Appropriations Committee announced a new bipartisan bill that includes $80 million funding to continue the Europa mission concept studies.[88][89]

- Europa Clipper — In July 2013 an updated concept for a flyby Europa mission called Europa Clipper was presented by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL).[90] The aim of Europa Clipper is to explore Europa in order to investigate its habitability, and to aid selecting sites for a future lander. The Europa Clipper would not orbit Europa, but instead orbit Jupiter and conduct 45 low-altitude flybys of Europa during its envisioned mission. The probe would carry an ice-penetrating radar, short-wave infrared spectrometer, topographical imager, and an ion- and neutral-mass spectrometer.

- Europa Orbiter — Its objective would be to characterize the extent of the ocean and its relation to the deeper interior. Instrument payload could include a radio subsystem, laser altimeter, magnetometer, Langmuir probe, and a mapping camera.[91][92]

- Europa Lander — It would investigate the moon's habitability and assess its astrobiological potential by confirming the existence and determining the characteristics of water within and below Europa's icy shell.[93]

Old proposals

In the early 2000s, Jupiter Europa Orbiter led by NASA and the Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter led by the ESA were proposed together as an Outer Planet Flagship Mission to Jupiter's icy moons, and called Europa Jupiter System Mission with a planned launch in 2020.[95] In 2009 it was given priority over Titan Saturn System Mission.[96] At that time, there was competition from other proposals.[97] Japan proposed Jupiter Magnetospheric Orbiter. Russia expressed interest in sending Europa Lander as part of the international effort.[98] The overall plan collapsed in the early 2010s.[94]

Jovian Europa Orbiter was an ESA Cosmic Vision concept study from 2007. Another concept was Ice Clipper,[99] which would have used an impactor similar to the Deep Impact mission—it would make a controlled crash into the surface of Europa, generating a plume of debris that would then be collected by a small spacecraft flying through the plume.[100][101]

Artist's concept of the cryobot (a thermal drill, seen upper left) and its deployed 'hydrobot' submersible

Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (JIMO) was a partially developed fission-powered spacecraft with ion thrusters that was cancelled in 2006.[81][102] It was part of Project Prometheus.[102] The Europa Lander Mission proposed a small nuclear-powered Europa lander for JIMO.[103] It would travel with the orbiter, which would also function as a communication relay to Earth.[103]

The Europa Orbiter received a go-ahead in 1999 but was canceled in 2002. This orbiter featured a special radar that would allow it to scan below the surface.[32]

More ambitious ideas have been put forward including an impactor in combination with a thermal drill to search for biosignatures that might be frozen in the shallow subsurface.[104][105]

Another proposal put forward in 2001 calls for a large nuclear-powered "melt probe" (cryobot) that would melt through the ice until it reached an ocean below.[81][106] Once it reached the water, it would deploy an autonomous underwater vehicle (hydrobot) that would gather information and send it back to Earth.[107] Both the cryobot and the hydrobot would have to undergo some form of extreme sterilization to prevent detection of Earth organisms instead of native life and to prevent contamination of the subsurface ocean.[108] This proposed mission has not yet reached a serious planning stage.[109]

Potential for extraterrestrial life

A black smoker in the Atlantic Ocean. Driven by geothermal energy, this and other types of hydrothermal vents create chemical disequilibria that can provide energy sources for life.

Europa has emerged as one of the top locations in the Solar System in terms of potential habitability and the possibility of hosting extraterrestrial life.[110] Life could exist in its under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean hydrothermal vents. Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to microbial life on Earth in the deep ocean.[82][111] So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa, but the likely presence of liquid water has spurred calls to send a probe there.[112]

Until the 1970s, life, at least as the concept is generally understood, was believed to be entirely dependent on energy from the Sun. Plants on Earth's surface capture energy from sunlight to photosynthesize sugars from carbon dioxide and water, releasing oxygen in the process, and are then consumed by oxygen-respiring animals, passing their energy up the food chain. Even life in the deep ocean, far below the reach of sunlight, was believed to obtain its nourishment either from the organic detritus raining down from the surface, or by eating animals that in turn depend on that stream of nutrients.[113] An environment's ability to support life was thus thought to depend on its access to sunlight.

This giant tube worm colony dwells beside a Pacific Ocean vent. Although the worms require oxygen (hence their blood-red color), methanogens and some other microbes in the vent communities do not.

However, in 1977, during an exploratory dive to the Galapagos Rift in the deep-sea exploration submersible Alvin, scientists discovered colonies of giant tube worms, clams, crustaceans, mussels, and other assorted creatures clustered around undersea volcanic features known as black smokers.[113] These creatures thrive despite having no access to sunlight, and it was soon discovered that they comprise an entirely independent food chain. Instead of plants, the basis for this food chain was a form of bacterium that derived its energy from oxidization of reactive chemicals, such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, that bubbled up from Earth's interior. This chemosynthesis revolutionized the study of biology by revealing that life need not be sunlight-dependent; it only requires water and an energy gradient in order to exist. It opened up a new avenue in astrobiology by massively expanding the number of possible extraterrestrial habitats.

Although the tube worms and other multicellular eukaryotic organisms around these hydrothermal vents respire oxygen and thus are indirectly dependent on photosynthesis, anaerobic chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea that inhabit these ecosystems provide a possible model for life in Europa's ocean.[77] The energy provided by tidal flexing drives active geological processes within Europa's interior, just as they do to a far more obvious degree on its sister moon Io. Although Europa, like the Earth, may possess an internal energy source from radioactive decay, the energy generated by tidal flexing would be several orders of magnitude greater than any radiological source.[114] However, such an energy source could never support an ecosystem as large and diverse as the photosynthesis-based ecosystem on Earth's surface.[115] Life on Europa could exist clustered around hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, or below the ocean floor, where endoliths are known to inhabit on Earth. Alternatively, it could exist clinging to the lower surface of Europa's ice layer, much like algae and bacteria in Earth's polar regions, or float freely in Europa's ocean.[116] However, if Europa's ocean were too cold, biological processes similar to those known on Earth could not take place. Similarly, if it were too salty, only extreme halophiles could survive in its environment.[116] In September 2009, planetary scientist Richard Greenberg calculated that cosmic rays impacting on Europa's surface convert some water ice into free oxygen (O2), which could then be absorbed into the ocean below as water wells up to fill cracks. Via this process, Greenberg estimates that Europa's ocean could eventually achieve an oxygen concentration greater than that of Earth's oceans within just a few million years. This would enable Europa to support not merely anaerobic microbial life but potentially larger, aerobic organisms such as fish.[117]

In 2006, Robert T. Pappalardo, an assistant professor in the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder said,

We've spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to understand if Mars was once a habitable environment. Europa today, probably, is a habitable environment. We need to confirm this ... but Europa, potentially, has all the ingredients for life ... and not just four billion years ago ... but today.[80]In November 2011, a team of researchers presented evidence in the journal Nature suggesting the existence of vast lakes of liquid water entirely encased in Europa's icy outer shell and distinct from a liquid ocean thought to exist farther down beneath the ice shell.[50][51] If confirmed, the lakes could be yet another potential habitat for life.

A paper published in March 2013 suggests that hydrogen peroxide is abundant across much of the surface of Jupiter's moon Europa.[118] The authors argue that if the peroxide on the surface of Europa mixes into the ocean below, it could be an important energy supply for simple forms of life, if life were to exist there. The scientists think hydrogen peroxide is an important factor for the habitability of the global liquid water ocean under Europa's icy crust because hydrogen peroxide decays to oxygen when mixed into liquid water.

On December 11, 2013, NASA reported the detection of "clay-like minerals" (specifically, phyllosilicates), often associated with organic materials, on the icy crust of Europa.[14] The presence of the minerals may have been the result of a collision with an asteroid or comet according to the scientists.[14]

Life on Earth could have been blasted into space by asteroid collisions and arrived on the moons of Jupiter in a process called lithopanspermia.[119]