The biological and geological future of Earth can be extrapolated based upon the estimated effects of several long-term influences. These include the chemistry at Earth's surface, the rate of cooling of the planet's interior, the gravitational interactions with other objects in the Solar System, and a steady increase in the Sun's luminosity. An uncertain factor in this extrapolation is the ongoing influence of technology introduced by humans, such as climate engineering,[2] which could cause significant changes to the planet.[3][4] The current Holocene extinction[5] is being caused by technology[6] and the effects may last for up to five million years.[7] In turn, technology may result in the extinction of humanity, leaving the planet to gradually return to a slower evolutionary pace resulting solely from long-term natural processes.[8][9]

Over time intervals of hundreds of millions of years, random celestial events pose a global risk to the biosphere, which can result in mass extinctions. These include impacts by comets or asteroids, and the possibility of a massive stellar explosion, called a supernova, within a 100-light-year radius of the Sun; known as a near-Earth supernova. Other large-scale geological events are more predictable. If the long-term effects of global warming are disregarded, Milankovitch theory predicts that the planet will continue to undergo glacial periods at least until the Quaternary glaciation comes to an end. These periods are caused by variations in eccentricity, axial tilt, and precession of the Earth's orbit.[10] As part of the ongoing supercontinent cycle, plate tectonics will probably result in a supercontinent in 250–350 million years. Some time in the next 1.5–4.5 billion years, the axial tilt of the Earth may begin to undergo chaotic variations, with changes in the axial tilt of up to 90°.[11]

The luminosity of the Sun will steadily increase, resulting in a rise in the solar radiation reaching the Earth. This will result in a higher rate of weathering of silicate minerals, which will cause a decrease in the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. In about 600 million years from now, the level of CO2 will fall below the level needed to sustain C3 carbon fixation photosynthesis used by trees. Some plants use the C4 carbon fixation method, allowing them to persist at CO

2 concentrations as low as 10 parts per million. However, the long-term trend is for plant life to die off altogether. The extinction of plants will be the demise of almost all animal life, since plants are the base of the food chain on Earth.[12]

In about one billion years, the solar luminosity will be 10% higher than at present. This will cause the atmosphere to become a "moist greenhouse", resulting in a runaway evaporation of the oceans. As a likely consequence, plate tectonics will come to an end, and with them the entire carbon cycle.[13] Following this event, in about 2−3 billion years, the planet's magnetic dynamo may cease, causing the magnetosphere to decay and leading to an accelerated loss of volatiles from the outer atmosphere. Four billion years from now, the increase in the Earth's surface temperature will cause a runaway greenhouse effect, heating the surface enough to melt it. By that point, all life on the Earth will be extinct.[14][15] The most probable fate of the planet is absorption by the Sun in about 7.5 billion years, after the star has entered the red giant phase and expanded beyond the planet's current orbit.

Human influence

Humans play a key role in the biosphere, with the large human population dominating many of Earth's ecosystems.[3] This has resulted in a widespread, ongoing mass extinction of other species during the present geological epoch, now known as the Holocene extinction. The large-scale loss of species caused by human influence since the 1950s has been called a biotic crisis, with an estimated 10% of the total species lost as of 2007.[6] At current rates, about 30% of species are at risk of extinction in the next hundred years.[16][DJS: Note this is in conflict with estimates of the number of spcecies on Earth and the rate humans are driving them extinct] The Holocene extinction event is the result of habitat destruction, the widespread distribution of invasive species, hunting, and climate change.[17][18] In the present day, human activity has had a significant impact on the surface of the planet. More than a third of the land surface has been modified by human actions, and humans use about 20% of global primary production.[4] The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased by close to 30% since the start of the Industrial Revolution.[3]The consequences of a persistent biotic crisis have been predicted to last for at least five million years.[7] It could result in a decline in biodiversity and homogenization of biotas, accompanied by a proliferation of species that are opportunistic, such as pests and weeds. Novel species may also emerge; in particular taxa that prosper in human-dominated ecosystems may rapidly diversify into many new species. Microbes are likely to benefit from the increase in nutrient-enriched environmental niches. No new species of existing large vertebrates are likely to arise and food chains will probably be shortened.[5][19]

There are multiple scenarios for known risks that can have a global impact on the planet. From the perspective of humanity, these can be subdivided into survivable risks and terminal risks. Risks that humanity pose to itself include climate change, the misuse of nanotechnology, a nuclear holocaust, warfare with a programmed superintelligence, a genetically engineered disease, or a disaster caused by a physics experiment. Similarly, several natural events may pose a doomsday threat, including a highly virulent disease, the impact of an asteroid or comet, runaway greenhouse effect, and resource depletion. There may also be the possibility of an infestation by an extraterrestrial lifeform.[20] The actual odds of these scenarios are difficult if not impossible to deduce.[8][9]

Should the human race become extinct, then the various features assembled by humanity will begin to decay. The largest structures have an estimated decay half-life of about 1,000 years. The last surviving structures would most likely be open pit mines, large landfills, major highways, wide canal cuts, and earth-fill flank dams. A few massive stone monuments like the pyramids at the Giza Necropolis or the sculptures at Mount Rushmore may still survive in some form after a million years.[9][a]

Random events

The Barringer Meteorite Crater in Flagstaff, Arizona, showing evidence of the impact of celestial objects upon the Earth

As the Sun orbits the Milky Way, wandering stars may approach close enough to have a disruptive influence on the Solar System.[21] A close stellar encounter may cause a significant reduction in the perihelion distances of comets in the Oort cloud—a spherical region of icy bodies orbiting within half a light year of the Sun.[22] Such an encounter can trigger a 40-fold increase in the number of comets reaching the inner Solar System. Impacts from these comets can trigger a mass extinction of life on Earth. These disruptive encounters occur at an average of once every 45 million years.[23] The mean time for the Sun to collide with another star in the solar neighborhood is approximately 3 × 1013 years, which is much longer than the estimated age of the Milky Way galaxy, at ~1.3 × 1010 years. This can be taken as an indication of the low likelihood of such an event occurring during the lifetime of the Earth.[24]

The energy release from the impact of an asteroid or comet with a diameter of 5–10 km (3.1–6.2 mi) or larger is sufficient to create a global environmental disaster and cause a statistically significant increase in the number of species extinctions. Among the deleterious effects resulting from a major impact event is a cloud of fine dust ejecta blanketing the planet, which lowers land temperatures by about 15 °C (27 °F) within a week and halts photosynthesis for several months. The mean time between major impacts is estimated to be at least 100 million years. During the last 540 million years, simulations demonstrated that such an impact rate is sufficient to cause 5–6 mass extinctions and 20–30 lower severity events. This matches the geologic record of significant extinctions during the Phanerozoic Eon. Such events can be expected to continue into the future.[25]

A supernova is a cataclysmic explosion of a star. Within the Milky Way galaxy, supernova explosions occur on average once every 40 years.[26] During the history of the Earth, multiple such events have likely occurred within a distance of 100 light years. Explosions inside this distance can contaminate the planet with radioisotopes and possibly impact the biosphere.[27] Gamma rays emitted by a supernova react with nitrogen in the atmosphere, producing nitrous oxides. These molecules cause a depletion of the ozone layer that protects the surface from ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. An increase in UV-B radiation of only 10–30% is sufficient to cause a significant impact to life; particularly to the phytoplankton that form the base of the oceanic food chain. A supernova explosion at a distance of 26 light years will reduce the ozone column density by half. On average, a supernova explosion occurs within 32 light years once every few hundred million years, resulting in a depletion of the ozone layer lasting several centuries.[28] Over the next two billion years, there will be about 20 supernova explosions and one gamma ray burst that will have a significant impact on the planet's biosphere.[29]

The incremental effect of gravitational perturbations between the planets causes the inner Solar System as a whole to behave chaotically over long time periods. This does not significantly affect the stability of the Solar System over intervals of a few million years or less, but over billions of years the orbits of the planets become unpredictable. Computer simulations of the Solar System's evolution over the next five billion years suggest that there is a small (less than 1%) chance that a collision could occur between Earth and either Mercury, Venus, or Mars.[30][31] During the same interval, the odds that the Earth will be scattered out of the Solar System by a passing star are on the order of one part in 105. In such a scenario, the oceans would freeze solid within several million years, leaving only a few pockets of liquid water about 14 km (8.7 mi) underground. There is a remote chance that the Earth will instead be captured by a passing binary star system, allowing the planet's biosphere to remain intact. The odds of this happening are about one chance in three million.[32]

Orbit and rotation

The gravitational perturbations of the other planets in the Solar System combine to modify the orbit of the Earth and the orientation of its spin axis. These changes can influence the planetary climate.[10][33][34][35] Despite such interactions, highly accurate simulations show that overall, Earth's orbit is likely to remain dynamically stable for billions of years into the future. In all 1,600 simulations, the planet's semimajor axis, eccentricity, and inclination remained nearly constant.[36]Glaciation

Historically, there have been cyclical ice ages in which glacial sheets periodically covered the higher latitudes of the continents. Ice ages may occur because of changes in ocean circulation and continentality induced by plate tectonics.[37] The Milankovitch theory predicts that glacial periods occur during ice ages because of astronomical factors in combination with climate feedback mechanisms. The primary astronomical drivers are a higher than normal orbital eccentricity, a low axial tilt (or obliquity), and the alignment of summer solstice with the aphelion.[10] Each of these effects occur cyclically. For example, the eccentricity changes over time cycles of about 100,000 and 400,000 years, with the value ranging from less than 0.01 up to 0.05.[38][39] This is equivalent to a change of the semiminor axis of the planet's orbit from 99.95% of the semimajor axis to 99.88%, respectively.[40]The Earth is passing through an ice age known as the quaternary glaciation, and is presently in the Holocene interglacial period. This period would normally be expected to end in about 25,000 years.[35] However, the increased rate of carbon dioxide release into the atmosphere by humans may delay the onset of the next glacial period until at least 50,000–130,000 years from now. On the other hand, a global warming period of finite duration (based on the assumption that fossil fuel use will cease by the year 2200) will probably only impact the glacial period for about 5,000 years. Thus, a brief period of global warming induced through a few centuries worth of greenhouse gas emission would only have a limited impact in the long term.[10]

Obliquity

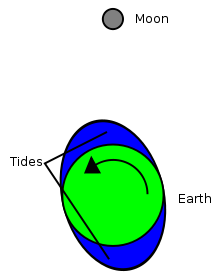

The rotational offset of the tidal bulge exerts a net torque on the Moon, boosting it while slowing the Earth's rotation. This image is not to scale.

The tidal acceleration of the Moon slows the rotation rate of the Earth and increases the Earth-Moon distance. Friction effects—between the core and mantle and between the atmosphere and surface—can dissipate the Earth's rotational energy. These combined effects are expected to increase the length of the day by more than 1.5 hours over the next 250 million years, and to increase the obliquity by about a half degree. The distance to the Moon will increase by about 1.5 Earth radii during the same period.[41]

Based on computer models, the presence of the Moon appears to stabilize the obliquity of the Earth, which may help the planet to avoid dramatic climate changes.[42] This stability is achieved because the Moon increases the precession rate of the Earth's spin axis, thereby avoiding resonances between the precession of the spin and precession of the planet's orbital plane (that is, the precession motion of the ecliptic).[43] However, as the semimajor axis of the Moon's orbit continues to increase, this stabilizing effect will diminish. At some point, perturbation effects will probably cause chaotic variations in the obliquity of the Earth, and the axial tilt may change by angles as high as 90° from the plane of the orbit. This is expected to occur between 1.5 and 4.5 billion years from now.[11]

A high obliquity would probably result in dramatic changes in the climate and may destroy the planet's habitability.[34] When the axial tilt of the Earth exceeds 54°, the yearly insolation at the equator is less than that at the poles. The planet could remain at an obliquity of 60° to 90° for periods as long as 10 million years.[44]

Geodynamics

Pangaea was the last supercontinent to form before the present.

Tectonics-based events will continue to occur well into the future and the surface will be steadily reshaped by tectonic uplift, extrusions, and erosion. Mount Vesuvius can be expected to erupt about 40 times over the next 1,000 years. During the same period, about five to seven earthquakes of magnitude 8 or greater should occur along the San Andreas Fault, while about 50 magnitude 9 events may be expected worldwide. Mauna Loa should experience about 200 eruptions over the next 1,000 years, and the Old Faithful Geyser will likely cease to operate. The Niagara Falls will continue to retreat upstream, reaching Buffalo in about 30,000–50,000 years.[9]

In 10,000 years, the post-glacial rebound of the Baltic Sea will have reduced the depth by about 90 m (300 ft). The Hudson Bay will decrease in depth by 100 m over the same period.[31] After 100,000 years, the island of Hawaii will have shifted about 9 km (5.6 mi) to the northwest. The planet may be entering another glacial period by this time.[9]

Continental drift

The theory of plate tectonics demonstrates that the continents of the Earth are moving across the surface at the rate of a few centimeters per year. This is expected to continue, causing the plates to relocate and collide. Continental drift is facilitated by two factors: the energy generation within the planet and the presence of a hydrosphere. With the loss of either of these, continental drift will come to a halt.[45] The production of heat through radiogenic processes is sufficient to maintain mantle convection and plate subduction for at least the next 1.1 billion years.[46]At present, the continents of North and South America are moving westward from Africa and Europe. Researchers have produced several scenarios about how this will continue in the future.[47] These geodynamic models can be distinguished by the subduction flux, whereby the oceanic crust moves under a continent. In the introversion model, the younger, interior, Atlantic ocean becomes preferentially subducted and the current migration of North and South America is reversed. In the extroversion model, the older, exterior, Pacific ocean remains preferentially subducted and North and South America migrate toward eastern Asia.[48][49]

As the understanding of geodynamics improves, these models will be subject to revision. In 2008, for example, a computer simulation was used to predict that a reorganization of the mantle convection will occur over the next 100 million years, causing a supercontinent composed of Africa, Eurasia, Australia, Antarctica and South America to form around Antarctica.[50]

Regardless of the outcome of the continental migration, the continued subduction process causes water to be transported to the mantle. After a billion years from the present, a geophysical model gives an estimate that 27% of the current ocean mass will have been subducted. If this process were to continue unmodified into the future, the subduction and release would reach an equilibrium after 65% of the current ocean mass has been subducted.[51]

Introversion

A rough approximation of Pangaea Ultima, one of the three models for a future supercontinent.

Christopher Scotese and his colleagues have mapped out the predicted motions several hundred million years into the future as part of the Paleomap Project.[47] In their scenario, 50 million years from now the Mediterranean sea may vanish and the collision between Europe and Africa will create a long mountain range extending to the current location of the Persian Gulf. Australia will merge with Indonesia, and Baja California will slide northward along the coast. New subduction zones may appear off the eastern coast of North and South America, and mountain chains will form along those coastlines. To the south, the migration of Antarctica to the north will cause all of its ice sheets to melt. This, along with the melting of the Greenland ice sheets, will raise the average ocean level by 90 m (300 ft). The inland flooding of the continents will result in climate changes.[47]

As this scenario continues, by 100 million years from the present the continental spreading will have reached its maximum extent and the continents will then begin to coalesce. In 250 million years, North America will collide with Africa while South America will wrap around the southern tip of Africa. The result will be the formation of a new supercontinent (sometimes called Pangaea Ultima), with the Pacific Ocean stretching across half the planet. The continent of Antarctica will reverse direction and return to the South Pole, building up a new ice cap.[52]

Extroversion

The first scientist to extrapolate the current motions of the continents was Canadian geologist Paul F. Hoffman of Harvard University. In 1992, Hoffman predicted that the continents of North and South America would continue to advance across the Pacific Ocean, pivoting about Siberia until they begin to merge with Asia. He dubbed the resulting supercontinent, Amasia.[53][54] Later, in the 1990s, Roy Livermore calculated a similar scenario. He predicted that Antarctica would start to migrate northward, and east Africa and Madagascar would move across the Indian Ocean to collide with Asia.[55]In an extroversion model, the closure of the Pacific Ocean would be complete in about 350 million years.[56] This marks the completion of the current supercontinent cycle, wherein the continents split apart and then rejoin each other about every 400–500 million years.[57] Once the supercontinent is built, plate tectonics may enter a period of inactivity as the rate of subduction drops by an order of magnitude. This period of stability could cause an increase in the mantle temperature at the rate of 30–100 °C (54–180 °F) every 100 million years, which is the minimum lifetime of past supercontinents. As a consequence, volcanic activity may increase.[49][56]

Supercontinent

The formation of a supercontinent can dramatically affect the environment. The collision of plates will result in mountain building, thereby shifting weather patterns. Sea levels may fall because of increased glaciation.[58] The rate of surface weathering can rise, resulting in an increase in the rate that organic material is buried. Supercontinents can cause a drop in global temperatures and an increase in atmospheric oxygen. This, in turn, can affect the climate, further lowering temperatures. All of these changes can result in more rapid biological evolution as new niches emerge.[59]The formation of a supercontinent insulates the mantle. The flow of heat will be concentrated, resulting in volcanism and the flooding of large areas with basalt. Rifts will form and the supercontinent will split up once more.[60] The planet may then experience a warming period, as occurred during the Cretaceous period.[59]

Solidification of the outer core

The iron-rich core region of the Earth is divided into a 1,220 km (760 mi) radius solid inner core and a 3,480 km (2,160 mi) radius liquid outer core.[61] The rotation of the Earth creates convective eddies in the outer core region that cause it to function as a dynamo.[62] This generates a magnetosphere about the Earth that deflects particles from the solar wind, which prevents significant erosion of the atmosphere from sputtering. As heat from the core is transferred outward toward the mantle, the net trend is for the inner boundary of the liquid outer core region to freeze, thereby releasing thermal energy and causing the solid inner core to grow.[63] This iron crystallization process has been ongoing for about a billion years. In the modern era, the radius of the inner core is expanding at an average rate of roughly 0.5 mm (0.02 in) per year, at the expense of the outer core.[64] Nearly all of the energy needed to power the dynamo is being supplied by this process of inner core formation.[65]The growth of the inner core may be expected to consume most of the outer core by some 3–4 billion years from now, resulting in a nearly solid core composed of iron and other heavy elements. The surviving liquid envelope will mainly consist of lighter elements that will undergo less mixing.[66] Alternatively, if at some point plate tectonics comes to an end, the interior will cool less efficiently, which may end the growth of the inner core. In either case, this can result in the loss of the magnetic dynamo. Without a functioning dynamo, the magnetic field of the Earth will decay in a geologically short time period of roughly 10,000 years.[67] The loss of the magnetosphere will cause an increase in erosion of light elements, particularly hydrogen, from the Earth's outer atmosphere into space, resulting in less favorable conditions for life.[68]

Solar evolution

The energy generation of the Sun is based upon thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium. This occurs in the core region of the star using the proton–proton chain reaction process. Because there is no convection in the solar core, the helium concentration builds up in that region without being distributed throughout the star. The temperature at the core of the Sun is too low for nuclear fusion of helium atoms through the triple-alpha process, so these atoms do not contribute to the net energy generation that is needed to maintain hydrostatic equilibrium of the Sun.[69]At present, nearly half the hydrogen at the core has been consumed, with the remainder of the atoms consisting primarily of helium. As the number of hydrogen atoms per unit mass decreases, so too does their energy output provided through nuclear fusion. This results in a decrease in pressure support, which causes the core to contract until the increased density and temperature bring the core pressure into equilibrium with the layers above. The higher temperature causes the remaining hydrogen to undergo fusion at a more rapid rate, thereby generating the energy needed to maintain the equilibrium.[69]

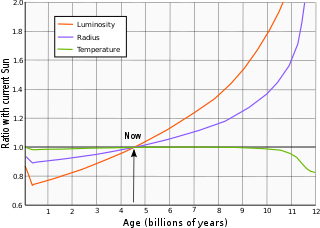

Evolution of the Sun's luminosity, radius and effective temperature compared to the present Sun. After Ribas (2010).[70]

The result of this process has been a steady increase in the energy output of the Sun. When the Sun first became a main sequence star, it radiated only 70% of the current luminosity. The luminosity has increased in a nearly linear fashion to the present, rising by 1% every 110 million years.[71] Likewise, in three billion years the Sun is expected to be 33% more luminous. The hydrogen fuel at the core will finally be exhausted in five billion years, when the Sun will be 67% more luminous than at present. Thereafter the Sun will continue to burn hydrogen in a shell surrounding its core, until the luminosity reaches 121% above the present value. This marks the end of the Sun's main sequence lifetime, and thereafter it will pass through the subgiant stage and evolve into a red giant.[1]

By this time, the collision of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies should be underway. Although this could result in the Solar System being ejected from the newly combined galaxy, it is considered unlikely to have any adverse effect on the Sun or its planets.[72][73]

Climate impact

The rate of weathering of silicate minerals will increase as rising temperatures speed up chemical processes. This in turn will decrease the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, as these weathering processes convert carbon dioxide gas into solid carbonates. Within the next 600 million years from the present, the concentration of CO2 will fall below the critical threshold needed to sustain C3 photosynthesis: about 50 parts per million. At this point, trees and forests in their current forms will no longer be able to survive,[74] the last living trees being evergreen conifers.[75] However, C4 carbon fixation can continue at much lower concentrations, down to above 10 parts per million. Thus plants using C4 photosynthesis may be able to survive for at least 0.8 billion years and possibly as long as 1.2 billion years from now, after which rising temperatures will make the biosphere unsustainable.[76][77][78] Currently, C4 plants represent about 5% of Earth's plant biomass and 1% of its known plant species.[79] For example, about 50% of all grass species (Poaceae) use the C4 photosynthetic pathway,[80] as do many species in the herbaceous family Amaranthaceae.[81]When the levels of carbon dioxide fall to the limit where photosynthesis is barely sustainable, the proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is expected to oscillate up and down. This will allow land vegetation to flourish each time the level of carbon dioxide rises due to tectonic activity and animal life. However, the long term trend is for the plant life on land to die off altogether as most of the remaining carbon in the atmosphere becomes sequestered in the Earth.[82] Some microbes are capable of photosynthesis at concentrations of CO

2 of a few parts per million, so these life forms would probably disappear only because of rising temperatures and the loss of the biosphere.[76]

Plants—and, by extension, animals—could survive longer by evolving other strategies such as requiring less CO

2 for photosynthetic processes, becoming carnivorous, adapting to desiccation, or associating with fungi. These adaptations are likely to appear near the beginning of the moist greenhouse (see further).[75]

The loss of plant life will also result in the eventual loss of oxygen as well as ozone due to the respiration of animals, chemical reactions in the atmosphere, and volcanic eruptions. This will result in less attenuation of DNA-damaging ultraviolet radiation,[75] as well as the death of animals; the first animals to disappear would be large mammals, followed by small mammals, birds, amphibians and large fish, reptiles and small fish, and finally invertebrates. Before this happened it's expected that life would concentrate at refugia of lower temperature such as high elevations where less land surface area is available, thus restricting population sizes. Smaller animals would survive better than larger ones because of lesser oxygen requirements, while birds would fare better than mammals thanks to their ability to travel large distances looking for colder temperatures.[12]

In their work The Life and Death of Planet Earth, authors Peter D. Ward and Donald Brownlee have argued that some form of animal life may continue even after most of the Earth's plant life has disappeared. Ward and Brownlee use fossil evidence from the Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada, to determine the climate of the Cambrian Explosion, and use it to predict the climate of the future when rising global temperatures caused by a warming Sun and declining oxygen levels result in the final extinction of animal life. Initially, they expect that some insects, lizards, birds and small mammals may persist, along with sea life. However, without oxygen replenishment by plant life, they believe that animals would probably die off from asphyxiation within a few million years. Even if sufficient oxygen were to remain in the atmosphere through the persistence of some form of photosynthesis, the steady rise in global temperature would result in a gradual loss of biodiversity.[82]

As temperatures continue to rise, the last animal life will be driven back toward the poles, and possibly underground. They would become primarily active during the polar night, aestivating during the polar day due to the intense heat. Much of the surface would become a barren desert and life would primarily be found in the oceans.[82] However, due to a decrease of the amount or organic matter coming to the oceans from the land as well as oxygen in the water,[75] life would disappear there too following a similar path to that on Earth's surface. This process would start with the loss of freshwater species and conclude with invertebrates,[12] particularly those that do not depend on living plants such as termites or those near hydrothermal vents such as worms of the genus Riftia.[75] As a result of these processes, multi-cellular lifeforms may be extinct in about 800 million years, and eukaryotes in 1.3 billion years, leaving only the prokaryotes.[83]

Loss of oceans

The atmosphere of Venus is in a "supergreenhouse" state.

One billion years from now, about 27% of the modern ocean will have been subducted into the mantle. If this process were allowed to continue uninterrupted, it would reach an equilibrium state where 65% of the current surface reservoir would remain at the surface.[51] Once the solar luminosity is 10% higher than its current value, the average global surface temperature will rise to 320 K (47 °C; 116 °F). The atmosphere will become a "moist greenhouse" leading to a runaway evaporation of the oceans.[84][85] At this point, models of the Earth's future environment demonstrate that the stratosphere would contain increasing levels of water. These water molecules will be broken down through photodissociation by solar ultraviolet radiation, allowing hydrogen to escape the atmosphere. The net result would be a loss of the world's sea water by about 1.1 billion years from the present.[86][87] This will be a simple dramatic step in annihilating all life on Earth.

There will be two variations of this future warming feedback: the "moist greenhouse" where water vapor dominates the troposphere while water vapor starts to accumulate in the stratosphere (if the oceans evaporate very quickly), and the "runaway greenhouse" where water vapor becomes a dominant component of the atmosphere (if the oceans evaporate too slowly). The Earth will undergo rapid warming that could send its surface temperature to over 900 °C (1,650 °F) as the atmosphere will be totally overwhelmed by water vapor, causing its entire surface to melt and killing all life, perhaps in about three billion years. In this ocean-free era, there will continue to be surface reservoirs as water is steadily released from the deep crust and mantle,[51] where it is estimated there is an amount of water equivalent to several times that currently present in the Earth's oceans.[88] Some water may be retained at the poles and there may be occasional rainstorms, but for the most part the planet would be a dry desert with large dunefields covering its equator, and a few salt flats on what was once the ocean floor, similar to the ones in the Atacama Desert in Chile.[13]

With no water to serve as a lubricant, plate tectonics would very likely stop and the most visible signs of geological activity would be shield volcanoes located above mantle hotspots.[85][75] In these arid conditions the planet may retain some microbial and possibly even multi-cellular life.[85] Most of these microbes will be halophiles and life could find refuge in the atmosphere as has been proposed that could have happened on Venus.[75] However, the increasingly extreme conditions will likely lead to the extinction of the prokaryotes between 1.6 billion years[83] and 2.8 billion years from now, with the last of them living in residual ponds of water at high latitudes and heights or in caverns with trapped ice. However, underground life could last longer.[12] What happens next depends on the level of tectonic activity. A steady release of carbon dioxide by volcanic eruption could cause the atmosphere to enter a "supergreenhouse" state like that of the planet Venus. But, as stated above, without surface water, plate tectonics would probably come to a halt and most of the carbonates would remain securely buried[13] until the Sun became a red giant and its increased luminosity heated the rock to the point of releasing the carbon dioxide.[88]

The loss of the oceans could be delayed until two billion years in the future if the total atmospheric pressure were to decline. A lower atmospheric pressure would reduce the greenhouse effect, thereby lowering the surface temperature. This could occur if natural processes were to remove the nitrogen from the atmosphere. Studies of organic sediments has shown that at least 100 kilopascals (0.99 atm) of nitrogen has been removed from the atmosphere over the past four billion years; enough to effectively double the current atmospheric pressure if it were to be released. This rate of removal would be sufficient to counter the effects of increasing solar luminosity for the next two billion years.[89]

By 2.8 billion years from now, the surface temperature of the Earth will have reached 422 K (149 °C; 300 °F), even at the poles. At this point, any remaining life will be extinguished due to the extreme conditions. If the Earth loses its surface water by this point, the planet will stay in the same conditions until the Sun becomes a red giant.[85] If this scenario doesn't happen, then in about 3–4 billion years the amount of water vapour in the lower atmosphere will rise to 40% and a moist greenhouse effect will commence[89] once the luminosity from the Sun reaches 35–40% more than its present-day value.[86] A "runaway greenhouse" effect will ensue, causing the atmosphere to heat up and raising the surface temperature to around 1,600 K (1,330 °C; 2,420 °F). This is sufficient to melt the surface of the planet.[87][85] However, most of the atmosphere will be retained until the Sun has entered the red giant stage.[90]

With the extinction of life, 2.8 billion years from now it is also expected that Earth biosignatures will disappear, to be replaced by signatures caused by non-biological processes.[75]

Red giant stage

The size of the current Sun (now in the main sequence) compared to its estimated size during its red giant phase

Once the Sun changes from burning hydrogen at its core to burning hydrogen around its shell, the core will start to contract and the outer envelope will expand. The total luminosity will steadily increase over the following billion years until it reaches 2,730 times the Sun's current luminosity at the age of 12.167 billion years. Most of Earth's atmosphere will be lost to space and its surface will consist of a lava ocean with floating continents of metals and metal oxides as well as icebergs of refractory materials, with its surface temperature reaching more than 2,400 K (2,130 °C; 3,860 °F).[91] The Sun will experience more rapid mass loss, with about 33% of its total mass shed with the solar wind. The loss of mass will mean that the orbits of the planets will expand. The orbital distance of the Earth will increase to at most 150% of its current value.[71]

The most rapid part of the Sun's expansion into a red giant will occur during the final stages, when the Sun will be about 12 billion years old. It is likely to expand to swallow both Mercury and Venus, reaching a maximum radius of 1.2 AU (180,000,000 km). The Earth will interact tidally with the Sun's outer atmosphere, which would serve to decrease Earth's orbital radius. Drag from the chromosphere of the Sun would also reduce the Earth's orbit. These effects will act to counterbalance the effect of mass loss by the Sun, and the Earth will probably be engulfed by the Sun.[71]

The drag from the solar atmosphere may cause the orbit of the Moon to decay. Once the orbit of the Moon closes to a distance of 18,470 km (11,480 mi), it will cross the Earth's Roche limit. This means that tidal interaction with the Earth would break apart the Moon, turning it into a ring system. Most of the orbiting ring will then begin to decay, and the debris will impact the Earth. Hence, even if the Earth is not swallowed up by the Sun, the planet may be left moonless.[92] The ablation and vaporization caused by its fall on a decaying trajectory towards the Sun may remove Earth's crust and mantle, leaving just its core, which will finally be destroyed after at most 200 years.[93][94] Following this event, Earth's sole legacy will be a very slight increase (0.01%) of the solar metallicity.[95]§IIC

Post red-giant stage

The Helix nebula, a planetary nebula similar to what the Sun will produce in 8 billion years.

After fusing helium in its core to carbon, the Sun will begin to collapse again, evolving into a compact white dwarf star after ejecting its outer atmosphere as a planetary nebula. In 50 billion years, if the Earth and Moon are not engulfed by the Sun, they will become tidelocked, with each showing only one face to the other.[96][97] Thereafter, the tidal action of the Sun will extract angular momentum from the system, causing the lunar orbit to decay and the Earth's spin to accelerate.[98]

In about 65 billion years, it estimated that the Moon may end up colliding with the Earth, assuming they are not destroyed by the red giant Sun, due to the remaining energy of the Earth–Moon system being sapped by the remnant Sun, causing the Moon to slowly move inwards toward the Earth.[99]

Over time intervals of around 30 trillion years, the Sun will undergo a close encounter with another star. As a consequence, the orbits of their planets can become disrupted, potentially ejecting them from the system entirely.[100] If Earth is not destroyed by the expanding red giant Sun in 7.6 billion years and not ejected from its orbit by a stellar encounter, its ultimate fate will be that it collides with the black dwarf Sun due to the decay of its orbit via gravitational radiation, in 1020 (100 quintillion) years.[101]