From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Descartes claimed that non-human animals could be explained reductively as

automata —

De homine, 1662.

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas

regarding the associations between phenomena which can be described in

terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena.

[1]

The Oxford Companion to Philosophy

suggests that reductionism is "one of the most used and abused terms in

the philosophical lexicon" and suggests a three part division:

[2]

- Ontological reductionism: a belief that the whole of reality consists of a minimal number of parts.

- Methodological reductionism: the scientific attempt to provide explanation in terms of ever smaller entities.

- Theory reductionism: the suggestion that a newer theory does

not replace or absorb an older one, but reduces it to more basic terms.

Theory reduction itself is divisible into three parts: translation,

derivation and explanation.[3]

Reductionism can be applied to any

phenomenon, including

objects,

explanations,

theories, and meanings.

[3][4] [5]

For the sciences, application of methodological reductionism attempts

explanation of entire systems in terms of their individual, constituent

parts and their interactions. For example, the temperature of a gas is

reduced to nothing but the average kinetic energy of its molecules in

motion.

Thomas Nagel speaks of

psychophysical reductionism (the attempted reduction of psychological phenomena to physics and chemistry), as do others and

physico-chemical reductionism (the attempted reduction of biology to physics and chemistry), again as do others.

[6] In a very simplified and sometimes contested form, such reductionism is said to imply that a system is

nothing but the sum of its parts.

[4][7]

However, a more nuanced opinion is that a system is composed entirely

of its parts, but the system will have features that none of the parts

have.

[8] "The point of mechanistic explanations is usually showing

how the higher level features arise from the parts."

[7]

Other definitions are used by other authors. For example, what

John Polkinghorne terms

conceptual or

epistemological reductionism

[4] is the definition provided by

Simon Blackburn[9] and by

Jaegwon Kim:

[10]

that form of reductionism concerning a program of replacing the facts

or entities entering statements claimed to be true in one type of

discourse with other facts or entities from another type, thereby

providing a relationship between them. Such an association is provided

where the same idea can be expressed by "levels" of explanation, with

higher levels reducible if need be to lower levels. This use of levels

of understanding in part expresses our human limitations in remembering

detail. However, "most philosophers would insist that our role in

conceptualizing reality [our need for an hierarchy of "levels" of

understanding] does not change the fact that different levels of

organization in reality do have different

properties."

[8]

Reductionism strongly represents a certain perspective of

causality.

In a reductionist framework, the phenomena that can be explained

completely in terms of relations between other more fundamental

phenomena, are termed

epiphenomena.

Often there is an implication that the epiphenomenon exerts no causal

agency on the fundamental phenomena that explain it. The epiphenomena

are sometimes said to be "nothing but" the outcome of the workings of

the fundamental phenomena, although the epiphenomena might be more

clearly and efficiently described in very different terms. There is a

tendency to avoid considering an epiphenomenon as being important in its

own right. This attitude may extend to cases where the fundamentals are

not obviously able to explain the epiphenomena, but are expected to by

the speaker. In this way, for example, morality can be deemed to be

"nothing but" evolutionary adaptation, and consciousness can be

considered "nothing but" the outcome of neurobiological processes.

Reductionism should be distinguished from

eliminationism:

reductionists do not deny the existence of phenomena, but explain them

in terms of another reality; eliminationists deny the existence of the

phenomena themselves. For example, eliminationists deny the existence of

life by their explanation in terms of physical and chemical processes.

Reductionism also does not preclude the existence of what might be termed

emergent phenomena,

but it does imply the ability to understand those phenomena completely

in terms of the processes from which they are composed. This

reductionist understanding is very different from

emergentism, which intends that what emerges in "emergence" is more than the sum of the processes from which it emerges.

[11]

Types

Most philosophers delineate three types of reductionism and anti-reductionism.

[2]

Ontological reductionism

Ontological

reductionism is the belief that reality is composed of a minimum number

of kinds of entities or substances. This claim is usually

metaphysical, and is most commonly a form of

monism, in effect claiming that all objects, properties and events are reducible to a single substance. (A

dualist

who is an ontological reductionist would believe that everything is

reducible to two substances — as one possible example, a dualist might

claim that reality is composed of "

matter" and "

spirit".)

Richard Jones divides ontological reductionism into two: the

reductionism of substances (e.g., the reduction of mind to matter) and

the reduction of the number of structures operating in nature (e.g., the

reduction of one physical force to another). This permits scientists

and philosophers to affirm the former while being anti-reductionists

regarding the latter.

[12]

Nancey Murphy

has claimed that there are two species of ontological reductionism: one

that denies that wholes are anything more than their parts; and the

stronger thesis of atomist reductionism that wholes are not "really

real". She admits that the phrase "really real" is apparently senseless

but nonetheless has tried to explicate the supposed difference between

the two.

[13]

Ontological reductionism denies the idea of ontological

emergence, and claims that emergence is an

epistemological phenomenon that only exists through analysis or description of a system, and does not exist fundamentally.

[14]

Ontological reductionism takes two different forms:

token ontological reductionism and

type ontological reductionism.

Token ontological reductionism is the idea that every item that

exists is a sum item. For perceivable items, it affirms that every

perceivable item is a sum of items with a lesser degree of complexity. Token ontological reduction of biological things to chemical things is

generally accepted.

Type ontological reductionism is the idea that every type of item is a

sum type of item, and that every perceivable type of item is a sum of

types of items with a lesser degree of complexity. Type ontological

reduction of biological things to chemical things is often rejected.

[15]

Michael Ruse has criticized ontological reductionism as an improper argument against

vitalism.

[16]

Methodological reductionism

Methodological

reductionism is the position that the best scientific strategy is to

attempt to reduce explanations to the smallest possible entities.

Methodological reductionism would thus include the claim that the atomic

explanation of a substance's boiling point is preferable to the

chemical explanation, and that an explanation based on even smaller

particles (

quarks and

leptons, perhaps) would be even better.

[citation needed]

Methodological reductionism, therefore, is the opinion that all

scientific theories either can or should be reduced to a single

super~theory through the process of theoretical reduction.

Theory reductionism

Theory reduction is the process by which one theory absorbs another. For example, both

Kepler's laws of the motion of the

planets and

Galileo's

theories of motion formulated for terrestrial objects are reducible to

Newtonian theories of mechanics because all the explanatory power of the

former are contained within the latter. Furthermore, the reduction is

considered to be beneficial because

Newtonian mechanics

is a more general theory—- that is, it explains more events than

Galileo's or Kepler's. Theoretical reduction, therefore, is the

reduction of one explanation or theory to another—- that is, it is the

absorption of one of our ideas about a particular item into another

idea.

In science

Reductionist thinking and methods form the basis for many of the well-developed topics of modern

science, including much of

physics,

chemistry and

cell biology.

Classical mechanics in particular is seen as a reductionist framework, and

statistical mechanics can be considered as a reconciliation of

macroscopic thermodynamic laws with the reductionist method of explaining macroscopic properties in terms of

microscopic components.

In science, reductionism implies that certain topics of study are

based on areas that study smaller spatial scales or organizational

units. While it is commonly accepted that the foundations of

chemistry are based in

physics, and

molecular biology

is based on chemistry, similar statements become controversial when one

considers less rigorously defined intellectual pursuits. For example,

claims that

sociology is based on

psychology, or that

economics is based on

sociology and

psychology

would be met with reservations. These claims are difficult to

substantiate even though there are obvious associations between these

topics (for instance, most would agree that

psychology can affect and inform

economics). The limit of reductionism's usefulness stems from

emergent properties of

complex systems, which are more common at certain levels of organization. For example, certain aspects of

evolutionary psychology and

sociobiology are rejected by some who claim that complex systems are inherently irreducible and that a

holistic method is needed to understand them.

Some strong reductionists believe that the behavioral sciences should

become "genuine" scientific disciplines based on genetic biology, and

on the systematic study of culture (see Richard Dawkins's concept of

memes). In his book

The Blind Watchmaker,

Dawkins introduced the term "hierarchical reductionism"

[17]

to describe the opinion that complex systems can be described with a

hierarchy of organizations, each of which is only described in terms of

objects one level down in the hierarchy. He provides the example of a

computer, which using hierarchical reductionism is explained in terms of

the operation of

hard drives, processors, and memory, but not on the level of

logic gates, or on the even simpler level of electrons in a

semiconductor medium.

Others argue that inappropriate use of reductionism limits our understanding of complex systems. In particular, ecologist

Robert Ulanowicz

says that science must develop techniques to study ways in which larger

scales of organization influence smaller ones, and also ways in which

feedback loops create structure at a given level, independently of

details at a lower level of organization. He advocates (and uses)

information theory as a framework to study

propensities in natural systems.

[18] Ulanowicz attributes these criticisms of reductionism to the philosopher

Karl Popper and biologist

Robert Rosen.

[19]

The idea that phenomena such as

emergence and work within the topic of

complex systems theory pose limits to reductionism has been advocated by

Stuart Kauffman.

[20] Emergence is especially relevant when systems exhibit historicity.

[21] Emergence is strongly related to

nonlinearity.

[22]

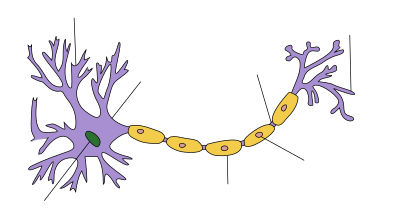

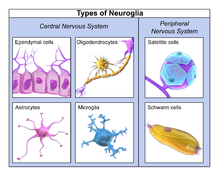

The limits of the application of reductionism are claimed to be

especially evident at levels of organization with higher amounts of

complexity, including living

cells,

[23] neural networks,

ecosystems,

society, and other systems formed from assemblies of large numbers of diverse components linked by multiple

feedback loops.

[23][24]

Nobel laureate Philip Warren Anderson used the idea that

symmetry breaking is an example of an emergent phenomenon in his 1972

Science paper "More is different" to make an argument about the limitations of reductionism.

[25] One observation he made was that the sciences can be arranged roughly in a linear hierarchy —

particle physics,

solid state physics,

chemistry,

molecular biology,

cellular biology,

physiology,

psychology,

social sciences —

in that the elementary entities of one science obeys the principles of

the science that precedes it in the hierarchy; yet this does not imply

that one science is just an applied version of the science that precedes

it. He writes that "At each stage, entirely new laws, concepts and

generalizations are necessary, requiring inspiration and creativity to

just as great a degree as in the previous one. Psychology is not applied

biology nor is biology applied chemistry."

Disciplines such as

cybernetics and

systems theory

imply non-reductionism, sometimes to the extent of explaining phenomena

at a given level of hierarchy in terms of phenomena at a higher level,

in a sense, the opposite of reductionism.

[26]

In mathematics

In

mathematics,

reductionism can be interpreted as the philosophy that all mathematics

can (or ought to) be based on a common foundation, which for modern

mathematics is usually

axiomatic set theory.

Ernst Zermelo

was one of the major advocates of such an opinion; he also developed

much of axiomatic set theory. It has been argued that the generally

accepted method of justifying mathematical

axioms by their usefulness in common practice can potentially weaken Zermelo's reductionist claim.

[27]

Jouko Väänänen has argued for

second-order logic as a foundation for mathematics instead of set theory,

[28] whereas others have argued for

category theory as a foundation for certain aspects of mathematics.

[29][30]

The

incompleteness theorems of

Kurt Gödel,

published during 1931, caused doubt about the attainability of an

axiomatic foundation for all of mathematics. Any such foundation would

have to include axioms powerful enough to describe the arithmetic of the

natural numbers (a subset of all mathematics). Yet Gödel proved that

for any self-consistent recursive axiomatic system powerful enough to

describe the arithmetic of the natural numbers, there are propositions

about the natural numbers that cannot be proved from the axioms, but

which we can prove in the natural language with which we described the

axioms. Such propositions are known as formally undecidable

propositions. For example, the

continuum hypothesis is undecidable in the

Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory as shown by

Cohen.

In religion

Religious

reductionism generally attempts to explain religion by explaining it in

terms of nonreligious causes. A few examples of reductionistic

explanations for the presence of religion are: that religion can be

reduced to humanity's conceptions of right and wrong, that religion is

fundamentally a primitive attempt at controlling our environments, that

religion is a way to explain the existence of a physical world, and that

religion confers an enhanced survivability for members of a group and

so is reinforced by

natural selection.

[31] Anthropologists

Edward Burnett Tylor and

James George Frazer employed some

religious reductionist arguments.

[32]

Sigmund Freud held that religion is nothing more than an illusion, or

even a mental illness, and Marx claimed that religion is "the sigh of

the oppressed," and the

opium of the people

providing only "the illusory happiness of the people," thus providing

two influential examples of reductionistic views against the idea of

religion.

In linguistics

Linguistic

reductionism is the idea that everything can be described or explained

by a language with a limited number of concepts, and combinations of

those concepts.

[33] An example is the language

Toki Pona.

In philosophy

The concept of

downward causation poses an alternative to reductionism within philosophy. This opinion is developed by

Peter Bøgh Andersen,

Claus Emmeche,

Niels Ole Finnemann, and

Peder Voetmann Christiansen,

among others. These philosophers explore ways in which one can talk

about phenomena at a larger-scale level of organization exerting causal

influence on a smaller-scale level, and find that some, but not all

proposed types of downward causation are compatible with science. In

particular, they find that constraint is one way in which downward

causation can operate.

[34] The notion of causality as constraint has also been explored as a way to shed light on scientific concepts such as

self-organization,

natural selection,

adaptation, and control.

[35]

Free will

Philosophers of the Enlightenment worked to insulate human free will from reductionism.

Descartes

separated the material world of mechanical necessity from the world of

mental free will. German philosophers introduced the concept of the "

noumenal" realm that is not governed by the deterministic laws of "

phenomenal" nature, where every event is completely determined by chains of causality.

[36] The most influential formulation was by

Immanuel Kant,

who distinguished between the causal deterministic framework the mind

imposes on the world—- the phenomenal realm—- and the world as it exists

for itself, the noumenal realm, which included free will. To insulate

theology from reductionism, 19th century post-Enlightenment German

theologians, especially

Friedrich Schleiermacher and

Albrecht Ritschl, used the

Romantic

method of basing religion on the human spirit, so that it is a person's

feeling or sensibility about spiritual matters that comprises religion.

[37]

Antireductionism

The anti-reductionist considers as minimum requirement upon the

reductionist: "At the very least the anti-reductionist is owed an

account of why the intuitions arise if they are not accurate."

[38]

A contrast to reductionism is

holism or

emergentism.

Holism is the idea that items can have properties, (emergent

properties), as a whole that are not explainable from the sum of their

parts. The principle of holism was summarized concisely by

Aristotle in the

Metaphysics: "The whole is more than the sum of its parts".

Alternatives

The development of

systems thinking has provided methods for describing issues in a

holistic rather than a reductionist way, and many scientists use a

holistic paradigm.

[39] When the terms are used in a scientific context, holism and reductionism refer primarily to what sorts of

models

or theories offer valid explanations of the natural world; the

scientific method of falsifying hypotheses, checking empirical data

against theory, is largely unchanged, but the method guides which

theories are considered. The conflict between reductionism and holism in

science is not universal—- it usually concerns whether or not a

holistic or reductionist method is appropriate in the context of

studying a specific system or phenomenon.

In many cases (such as the

kinetic theory

of gases), given a good understanding of the components of the system,

one can predict all the important properties of the system as a whole.

In other systems,

emergent properties of the system are said to be almost impossible to predict from knowledge of the parts of the system.

Complexity theory studies systems and properties of the latter type.

Alfred North Whitehead's

metaphysics opposed reductionism. He refers to this as the "fallacy of

the misplaced concreteness". His scheme was to frame a rational, general

understanding of phenomena, derived from our reality.

Sven Erik Jorgensen, an

ecologist, states both theoretical and practical arguments for a

holistic method in certain topics of science, especially

ecology.

He argues that many systems are so complex that it will not ever be

possible to describe all their details. Making an analogy to the

Heisenberg

uncertainty principle

in physics, he argues that many interesting and relevant ecological

phenomena cannot be replicated in laboratory conditions, and thus cannot

be measured or observed without influencing and changing the system in

some way. He also indicates the importance of interconnectedness in

biological systems. His opinion is that science can only progress by

outlining what questions are unanswerable and by using models that do

not attempt to explain everything in terms of smaller hierarchical

levels of organization, but instead model them on the scale of the

system itself, taking into account some (but not all) factors from

levels both higher and lower in the hierarchy.

[40]

Criticism

Fragmentalism is an alternative term for ontological reductionism,

[41] although

fragmentalism is frequently used in a

pejorative sense.

[42] Anti-realists use the term fragmentalism in arguments that the world does not exist of separable

entities, instead consisting of wholes. For example, advocates of this idea claim that:

The linear deterministic approach to nature and technology promoted a

fragmented perception of reality, and a loss of the ability to foresee,

to adequately evaluate, in all their complexity, global crises in

ecology, civilization and education.[43]

The term "fragmentalism" is usually applied to reductionist modes of thought, frequently with the related pejorative term of

scientism. This usage is popular amongst some ecological activists:

There is a need now to move away from scientism and the ideology of cause-and-effect determinism toward a radical empiricism, such as William James proposed, as an epistemology of science.[44]

These perspectives are not new and during the early twentieth century,

William James noted that rationalist science emphasized what he termed fragmentation and disconnection.

[45]

Such opinions also motivate many criticisms of the scientific method:

The scientific method only acknowledges monophasic consciousness. The

method is a specialized system that emphasizes studying small and

distinctive parts in isolation, which results in fragmented knowledge.[45]

An alternative usage of this term is in

cognitive psychology. Here,

George Kelly developed "constructive alternativism" as a form of

personal construct psychology,

this provided an alternative to what he considered "accumulative

fragmentalism". For this theory, knowledge is seen as the construction

of successful

mental models of the exterior world, rather than the accumulation of independent "nuggets of truth".

[46]