A definite integral of a function can be represented as the signed area of the region bounded by its graph.

In mathematics, an integral assigns numbers to functions in a way that can describe displacement, area, volume, and other concepts that arise by combining infinitesimal data. Integration is one of the two main operations of calculus, with its inverse operation, differentiation, being the other. Given a function f of a real variable x and an interval [a, b] of the real line, the definite integral

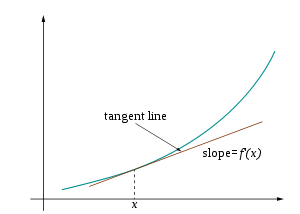

The operation of integration, up to an additive constant, is the inverse of the operation of differentiation. For this reason, the term integral may also refer to the related notion of the antiderivative, a function F whose derivative is the given function f. In this case, it is called an indefinite integral and is written:

History

Pre-calculus integration

The first documented systematic technique capable of determining integrals is the method of exhaustion of the ancient Greek astronomer Eudoxus (ca. 370 BC), which sought to find areas and volumes by breaking them up into an infinite number of divisions for which the area or volume was known. This method was further developed and employed by Archimedes in the 3rd century BC and used to calculate areas for parabolas and an approximation to the area of a circle.A similar method was independently developed in China around the 3rd century AD by Liu Hui, who used it to find the area of the circle. This method was later used in the 5th century by Chinese father-and-son mathematicians Zu Chongzhi and Zu Geng to find the volume of a sphere (Shea 2007; Katz 2004, pp. 125–126).

The next significant advances in integral calculus did not begin to appear until the 17th century. At this time, the work of Cavalieri with his method of Indivisibles, and work by Fermat, began to lay the foundations of modern calculus, with Cavalieri computing the integrals of xn up to degree n = 9 in Cavalieri's quadrature formula. Further steps were made in the early 17th century by Barrow and Torricelli, who provided the first hints of a connection between integration and differentiation. Barrow provided the first proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus. Wallis generalized Cavalieri's method, computing integrals of x to a general power, including negative powers and fractional powers.

Newton and Leibniz

The major advance in integration came in the 17th century with the independent discovery of the fundamental theorem of calculus by Newton and Leibniz. The theorem demonstrates a connection between integration and differentiation. This connection, combined with the comparative ease of differentiation, can be exploited to calculate integrals. In particular, the fundamental theorem of calculus allows one to solve a much broader class of problems. Equal in importance is the comprehensive mathematical framework that both Newton and Leibniz developed. Given the name infinitesimal calculus, it allowed for precise analysis of functions within continuous domains. This framework eventually became modern calculus, whose notation for integrals is drawn directly from the work of Leibniz.Formalization

While Newton and Leibniz provided a systematic approach to integration, their work lacked a degree of rigour. Bishop Berkeley memorably attacked the vanishing increments used by Newton, calling them "ghosts of departed quantities". Calculus acquired a firmer footing with the development of limits. Integration was first rigorously formalized, using limits, by Riemann. Although all bounded piecewise continuous functions are Riemann-integrable on a bounded interval, subsequently more general functions were considered—particularly in the context of Fourier analysis—to which Riemann's definition does not apply, and Lebesgue formulated a different definition of integral, founded in measure theory (a subfield of real analysis). Other definitions of integral, extending Riemann's and Lebesgue's approaches, were proposed. These approaches based on the real number system are the ones most common today, but alternative approaches exist, such as a definition of integral as the standard part of an infinite Riemann sum, based on the hyperreal number system.Historical notation

Isaac Newton used a small vertical bar above a variable to indicate integration, or placed the variable inside a box. The vertical bar was easily confused with or x′, which are used to indicate differentiation, and the box notation was difficult for printers to reproduce, so these notations were not widely adopted.The modern notation for the indefinite integral was introduced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1675 (Burton 1988, p. 359; Leibniz 1899, p. 154). He adapted the integral symbol, ∫, from the letter ſ (long s), standing for summa (written as ſumma; Latin for "sum" or "total"). The modern notation for the definite integral, with limits above and below the integral sign, was first used by Joseph Fourier in Mémoires of the French Academy around 1819–20, reprinted in his book of 1822 (Cajori 1929, pp. 249–250; Fourier 1822, §231).

Applications

Integrals are used extensively in many areas of mathematics as well as in many other areas that rely on mathematics.For example, in probability theory, integrals are used to determine the probability of some random variable falling within a certain range. Moreover, the integral under an entire probability density function must equal 1, which provides a test of whether a function with no negative values could be a density function or not.

Integrals can be used for computing the area of a two-dimensional region that has a curved boundary, as well as computing the volume of a three-dimensional object that has a curved boundary.

Integrals are also used in physics, in areas like kinematics to find quantities like displacement, time, and velocity. For example, in rectilinear motion, the displacement of an object over the time interval

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) is given by:

is given by:

is the velocity expressed as a function of time. The work done by a force

is the velocity expressed as a function of time. The work done by a force  (given as a function of position) from an initial position

(given as a function of position) from an initial position  to a final position

to a final position  is:

is:

Terminology and notation

Standard

The integral with respect to x of a real-valued function f(x) of a real variable x on the interval [a, b] is written as.

If the integral goes from a finite value a to the upper limit infinity, the integral expresses the limit of the integral from a to a value b as b goes to infinity. If the value of the integral gets closer and closer to a finite value, the integral is said to converge to that value. If not, the integral is said to diverge.

When the limits are omitted, as in

There are several extensions of the notation for integrals to encompass integration on unbounded domains and/or in multiple dimensions (see later sections of this article).

Meaning of the symbol dx

Historically, the symbol dx was taken to represent an infinitesimally "small piece" of the independent variable x to be multiplied by the integrand and summed up in an infinite sense. While this notion is still heuristically useful, later mathematicians have deemed infinitesimal quantities to be untenable from the standpoint of the real number system. In introductory calculus, the expression dx is therefore not assigned an independent meaning; instead, it is viewed as part of the symbol for integration and serves as its delimiter on the right side of the expression being integrated.In more sophisticated contexts, dx can have its own significance, the meaning of which depending on the particular area of mathematics being discussed. When used in one of these ways, the original Leibnitz notation is co-opted to apply to a generalization of the original definition of the integral. Some common interpretations of dx include: an integrator function in Riemann-Stieltjes integration (indicated by dα(x) in general), a measure in Lebesgue theory (indicated by dμ in general), or a differential form in exterior calculus (indicated by

in general). In the last case, even the letter d has an independent meaning — as the exterior derivative operator on differential forms.

in general). In the last case, even the letter d has an independent meaning — as the exterior derivative operator on differential forms.Conversely, in advanced settings, it is not uncommon to leave out dx when only the simple Riemann integral is being used, or the exact type of integral is immaterial. For instance, one might write

to express the linearity of the integral, a property shared by the Riemann integral and all generalizations thereof.

to express the linearity of the integral, a property shared by the Riemann integral and all generalizations thereof.

Variants

In modern Arabic mathematical notation, a reflected integral symbolor

.

Interpretations of the integral

Integrals appear in many practical situations. If a swimming pool is rectangular with a flat bottom, then from its length, width, and depth we can easily determine the volume of water it can contain (to fill it), the area of its surface (to cover it), and the length of its edge (to rope it). But if it is oval with a rounded bottom, all of these quantities call for integrals. Practical approximations may suffice for such trivial examples, but precision engineering (of any discipline) requires exact and rigorous values for these elements.

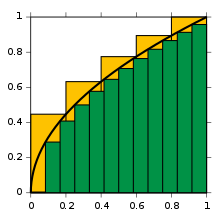

Approximations to integral of √x from 0 to 1, with 5 ■ (yellow) right endpoint partitions and 12 ■ (green) left endpoint partitions

To start off, consider the curve y = f(x) between x = 0 and x = 1 with f(x) = √x (see figure). We ask: what is the area under the function f, in the interval from 0 to 1?

We call this (yet unknown) area the (definite) integral of f. The notation for this integral will be

The key idea is the transition from adding finitely many differences of approximation points multiplied by their respective function values to using infinitely many fine, or infinitesimal steps. When this transition is completed in the above example, it turns out that the area under the curve within the stated bounds is 2/3.

The notation

Historically, after the failure of early efforts to rigorously interpret infinitesimals, Riemann formally defined integrals as a limit of weighted sums, so that the dx suggested the limit of a difference (namely, the interval width). Shortcomings of Riemann's dependence on intervals and continuity motivated newer definitions, especially the Lebesgue integral, which is founded on an ability to extend the idea of "measure" in much more flexible ways. Thus the notation

Formal definitions

There are many ways of formally defining an integral, not all of which are equivalent. The differences exist mostly to deal with differing special cases which may not be integrable under other definitions, but also occasionally for pedagogical reasons. The most commonly used definitions of integral are Riemann integrals and Lebesgue integrals.

Riemann integral

The Riemann integral is defined in terms of Riemann sums of functions with respect to tagged partitions of an interval. Let [a, b] be a closed interval of the real line; then a tagged partition of [a, b] is a finite sequenceFor all ε > 0 there exists δ > 0 such that, for any tagged partition [a, b] with mesh less than δ, we have

Lebesgue integral

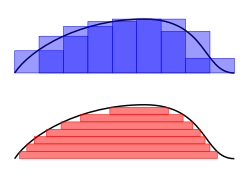

Riemann–Darboux's integration (top) and Lebesgue integration (bottom)

It is often of interest, both in theory and applications, to be able to pass to the limit under the integral. For instance, a sequence of functions can frequently be constructed that approximate, in a suitable sense, the solution to a problem. Then the integral of the solution function should be the limit of the integrals of the approximations. However, many functions that can be obtained as limits are not Riemann-integrable, and so such limit theorems do not hold with the Riemann integral. Therefore, it is of great importance to have a definition of the integral that allows a wider class of functions to be integrated.

Such an integral is the Lebesgue integral, that exploits the following fact to enlarge the class of integrable functions: if the values of a function are rearranged over the domain, the integral of a function should remain the same. Thus Henri Lebesgue introduced the integral bearing his name, explaining this integral thus in a letter to Paul Montel:

I have to pay a certain sum, which I have collected in my pocket. I take the bills and coins out of my pocket and give them to the creditor in the order I find them until I have reached the total sum. This is the Riemann integral. But I can proceed differently. After I have taken all the money out of my pocket I order the bills and coins according to identical values and then I pay the several heaps one after the other to the creditor. This is my integral.As Folland (1984, p. 56) puts it, "To compute the Riemann integral of f, one partitions the domain [a, b] into subintervals", while in the Lebesgue integral, "one is in effect partitioning the range of f ". The definition of the Lebesgue integral thus begins with a measure, μ. In the simplest case, the Lebesgue measure μ(A) of an interval A = [a, b] is its width, b − a, so that the Lebesgue integral agrees with the (proper) Riemann integral when both exist. In more complicated cases, the sets being measured can be highly fragmented, with no continuity and no resemblance to intervals.

Using the "partitioning the range of f " philosophy, the integral of a non-negative function f : R → R should be the sum over t of the areas between a thin horizontal strip between y = t and y = t + dt. This area is just μ{ x : f(x) > t} dt. Let f∗(t) = μ{ x : f(x) > t}. The Lebesgue integral of f is then defined by

A general measurable function f is Lebesgue-integrable if the sum of the absolute values of the areas of the regions between the graph of f and the x-axis is finite:

Other integrals

Although the Riemann and Lebesgue integrals are the most widely used definitions of the integral, a number of others exist, including:- The Darboux integral, which is constructed using Darboux sums and is equivalent to a Riemann integral, meaning that a function is Darboux-integrable if and only if it is Riemann-integrable. Darboux integrals have the advantage of being simpler to define than Riemann integrals.

- The Riemann–Stieltjes integral, an extension of the Riemann integral.

- The Lebesgue–Stieltjes integral, further developed by Johann Radon, which generalizes the Riemann–Stieltjes and Lebesgue integrals.

- The Daniell integral, which subsumes the Lebesgue integral and Lebesgue–Stieltjes integral without the dependence on measures.

- The Haar integral, used for integration on locally compact topological groups, introduced by Alfréd Haar in 1933.

- The Henstock–Kurzweil integral, variously defined by Arnaud Denjoy, Oskar Perron, and (most elegantly, as the gauge integral) Jaroslav Kurzweil, and developed by Ralph Henstock.

- The Itô integral and Stratonovich integral, which define integration with respect to semimartingales such as Brownian motion.

- The Young integral, which is a kind of Riemann–Stieltjes integral with respect to certain functions of unbounded variation.

- The rough path integral, which is defined for functions equipped with some additional "rough path" structure and generalizes stochastic integration against both semimartingales and processes such as the fractional Brownian motion.

Properties

Linearity

The collection of Riemann-integrable functions on a closed interval [a, b] forms a vector space under the operations of pointwise addition and multiplication by a scalar, and the operation of integrationLinearity, together with some natural continuity properties and normalisation for a certain class of "simple" functions, may be used to give an alternative definition of the integral. This is the approach of Daniell for the case of real-valued functions on a set X, generalized by Nicolas Bourbaki to functions with values in a locally compact topological vector space. See (Hildebrandt 1953) for an axiomatic characterisation of the integral.

Inequalities

A number of general inequalities hold for Riemann-integrable functions defined on a closed and bounded interval [a, b] and can be generalized to other notions of integral (Lebesgue and Daniell).- Upper and lower bounds. An integrable function f on [a, b], is necessarily bounded on that interval. Thus there are real numbers m and M so that m ≤ f (x) ≤ M for all x in [a, b]. Since the lower and upper sums of f over [a, b] are therefore bounded by, respectively, m(b − a) and M(b − a), it follows that

- Inequalities between functions. If f(x) ≤ g(x) for each x in [a, b] then each of the upper and lower sums of f is bounded above by the upper and lower sums, respectively, of g. Thus

-

This is a generalization of the above inequalities, as M(b − a) is the integral of the constant function with value M over [a, b].- In addition, if the inequality between functions is strict, then the inequality between integrals is also strict. That is, if f(x) < g(x) for each x in [a, b], then

- Subintervals. If [c, d] is a subinterval of [a, b] and f(x) is non-negative for all x, then

- Products and absolute values of functions. If f and g are two functions, then we may consider their pointwise products and powers, and absolute values:

-

If f is Riemann-integrable on [a, b] then the same is true for |f|, and

Moreover, if f and g are both Riemann-integrable then fg is also Riemann-integrable, and

This inequality, known as the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, plays a prominent role in Hilbert space theory, where the left hand side is interpreted as the inner product of two square-integrable functions f and g on the interval [a, b].

- Hölder's inequality. Suppose that p and q are two real numbers, 1 ≤ p, q ≤ ∞ with 1/p + 1/q = 1, and f and g are two Riemann-integrable functions. Then the functions |f|p and |g|q are also integrable and the following Hölder's inequality holds:

-

For p = q = 2, Hölder's inequality becomes the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

- Minkowski inequality. Suppose that p ≥ 1 is a real number and f and g are Riemann-integrable functions. Then | f |p, | g |p and | f + g |p are also Riemann-integrable and the following Minkowski inequality holds:

-

- An analogue of this inequality for Lebesgue integral is used in construction of Lp spaces.

Conventions

In this section, f is a real-valued Riemann-integrable function. The integral- Reversing limits of integration. If a > b then define

- Integrals over intervals of length zero. If a is a real number then

- Additivity of integration on intervals. If c is any element of [a, b], then

Fundamental theorem of calculus

The fundamental theorem of calculus is the statement that differentiation and integration are inverse operations: if a continuous function is first integrated and then differentiated, the original function is retrieved. An important consequence, sometimes called the second fundamental theorem of calculus, allows one to compute integrals by using an antiderivative of the function to be integrated.Statements of theorems

Fundamental theorem of calculus

Let f be a continuous real-valued function defined on a closed interval [a, b]. Let F be the function defined, for all x in [a, b], bySecond fundamental theorem of calculus

Let f be a real-valued function defined on a closed interval [a, b] that admits an antiderivative F on [a, b]. That is, f and F are functions such that for all x in [a, b],Calculating integrals

The second fundamental theorem allows many integrals to be calculated explicitly. For example, to calculate the integralExtensions

Improper integrals

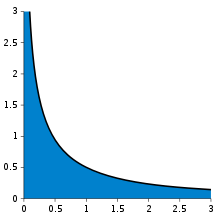

A "proper" Riemann integral assumes the integrand is defined and finite on a closed and bounded interval, bracketed by the limits of integration. An improper integral occurs when one or more of these conditions is not satisfied. In some cases such integrals may be defined by considering the limit of a sequence of proper Riemann integrals on progressively larger intervals.

If the interval is unbounded, for instance at its upper end, then the improper integral is the limit as that endpoint goes to infinity.

Multiple integration

Double integral as volume under a surface

Just as the definite integral of a positive function of one variable represents the area of the region between the graph of the function and the x-axis, the double integral of a positive function of two variables represents the volume of the region between the surface defined by the function and the plane that contains its domain. For example, a function in two dimensions depends on two real variables, x and y, and the integral of a function f over the rectangle R given as the Cartesian product of two intervals

![R=[a,b]\times [c,d]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3493a3bdcd7bd76960bb3d7b766bd6c6b1c4b3ee) can be written

can be written

Line integrals

A line integral sums together elements along a curve.

The concept of an integral can be extended to more general domains of integration, such as curved lines and surfaces. Such integrals are known as line integrals and surface integrals respectively. These have important applications in physics, as when dealing with vector fields.

A line integral (sometimes called a path integral) is an integral where the function to be integrated is evaluated along a curve. Various different line integrals are in use. In the case of a closed curve it is also called a contour integral.

The function to be integrated may be a scalar field or a vector field. The value of the line integral is the sum of values of the field at all points on the curve, weighted by some scalar function on the curve (commonly arc length or, for a vector field, the scalar product of the vector field with a differential vector in the curve). This weighting distinguishes the line integral from simpler integrals defined on intervals. Many simple formulas in physics have natural continuous analogs in terms of line integrals; for example, the fact that work is equal to force, F, multiplied by displacement, s, may be expressed (in terms of vector quantities) as:

Surface integrals

The definition of surface integral relies on splitting the surface into small surface elements.

A surface integral is a definite integral taken over a surface (which may be a curved set in space); it can be thought of as the double integral analog of the line integral. The function to be integrated may be a scalar field or a vector field. The value of the surface integral is the sum of the field at all points on the surface. This can be achieved by splitting the surface into surface elements, which provide the partitioning for Riemann sums.

For an example of applications of surface integrals, consider a vector field v on a surface S; that is, for each point x in S, v(x) is a vector. Imagine that we have a fluid flowing through S, such that v(x) determines the velocity of the fluid at x. The flux is defined as the quantity of fluid flowing through S in unit amount of time. To find the flux, we need to take the dot product of v with the unit surface normal to S at each point, which will give us a scalar field, which we integrate over the surface:

Contour integrals

In complex analysis, the integrand is a complex-valued function of a complex variable z instead of a real function of a real variable x. When a complex function is integrated along a curve in the complex plane, the integral is denoted as follows

in the complex plane, the integral is denoted as follows

.

Integrals of differential forms

A differential form is a mathematical concept in the fields of multivariable calculus, differential topology, and tensors. Differential forms are organized by degree. For example, a one-form is a weighted sum of the differentials of the coordinates, such as:A differential two-form is a sum of the form

measure oriented areas parallel to the coordinate two-planes. The symbol

measure oriented areas parallel to the coordinate two-planes. The symbol  denotes the wedge product, which is similar to the cross product

in the sense that the wedge product of two forms representing oriented

lengths represents an oriented area. A two-form can be integrated over

an oriented surface, and the resulting integral is equivalent to the

surface integral giving the flux of

denotes the wedge product, which is similar to the cross product

in the sense that the wedge product of two forms representing oriented

lengths represents an oriented area. A two-form can be integrated over

an oriented surface, and the resulting integral is equivalent to the

surface integral giving the flux of  .

.Unlike the cross product, and the three-dimensional vector calculus, the wedge product and the calculus of differential forms makes sense in arbitrary dimension and on more general manifolds (curves, surfaces, and their higher-dimensional analogs). The exterior derivative plays the role of the gradient and curl of vector calculus, and Stokes' theorem simultaneously generalizes the three theorems of vector calculus: the divergence theorem, Green's theorem, and the Kelvin-Stokes theorem.

Summations

The discrete equivalent of integration is summation. Summations and integrals can be put on the same foundations using the theory of Lebesgue integrals or time scale calculus.Computation

Analytical

The most basic technique for computing definite integrals of one real variable is based on the fundamental theorem of calculus. Let f(x) be the function of x to be integrated over a given interval [a, b]. Then, find an antiderivative of f; that is, a function F such that F′ = f on the interval. Provided the integrand and integral have no singularities on the path of integration, by the fundamental theorem of calculus,The most difficult step is usually to find the antiderivative of f. It is rarely possible to glance at a function and write down its antiderivative. More often, it is necessary to use one of the many techniques that have been developed to evaluate integrals. Most of these techniques rewrite one integral as a different one which is hopefully more tractable. Techniques include:

- Integration by substitution

- Integration by parts

- Inverse function integration

- Changing the order of integration

- Integration by trigonometric substitution

- Tangent half-angle substitution

- Integration by partial fractions

- Integration by reduction formulae

- Integration using parametric derivatives

- Integration using Euler's formula

- Euler substitution

- Differentiation under the integral sign

- Contour integration

Computations of volumes of solids of revolution can usually be done with disk integration or shell integration.

Specific results which have been worked out by various techniques are collected in the list of integrals.

Symbolic

Many problems in mathematics, physics, and engineering involve integration where an explicit formula for the integral is desired. Extensive tables of integrals have been compiled and published over the years for this purpose. With the spread of computers, many professionals, educators, and students have turned to computer algebra systems that are specifically designed to perform difficult or tedious tasks, including integration. Symbolic integration has been one of the motivations for the development of the first such systems, like Macsyma.A major mathematical difficulty in symbolic integration is that in many cases, a closed formula for the antiderivative of a rather simple-looking function does not exist. For instance, it is known that the antiderivatives of the functions exp(x2), xx and (sin x)/x cannot be expressed in the closed form involving only rational and exponential functions, logarithm, trigonometric functions and inverse trigonometric functions, and the operations of multiplication and composition; in other words, none of the three given functions is integrable in elementary functions, which are the functions which may be built from rational functions, roots of a polynomial, logarithm, and exponential functions. The Risch algorithm provides a general criterion to determine whether the antiderivative of an elementary function is elementary, and, if it is, to compute it. Unfortunately, it turns out that functions with closed expressions of antiderivatives are the exception rather than the rule. Consequently, computerized algebra systems have no hope of being able to find an antiderivative for a randomly constructed elementary function. On the positive side, if the 'building blocks' for antiderivatives are fixed in advance, it may be still be possible to decide whether the antiderivative of a given function can be expressed using these blocks and operations of multiplication and composition, and to find the symbolic answer whenever it exists. The Risch algorithm, implemented in Mathematica and other computer algebra systems, does just that for functions and antiderivatives built from rational functions, radicals, logarithm, and exponential functions.

Some special integrands occur often enough to warrant special study. In particular, it may be useful to have, in the set of antiderivatives, the special functions (like the Legendre functions, the hypergeometric function, the gamma function, the incomplete gamma function and so on — see Symbolic integration for more details). Extending the Risch's algorithm to include such functions is possible but challenging and has been an active research subject.

More recently a new approach has emerged, using D-finite functions, which are the solutions of linear differential equations with polynomial coefficients. Most of the elementary and special functions are D-finite, and the integral of a D-finite function is also a D-finite function. This provides an algorithm to express the antiderivative of a D-finite function as the solution of a differential equation.

This theory also allows one to compute the definite integral of a D-function as the sum of a series given by the first coefficients, and provides an algorithm to compute any coefficient.

Numerical

Some integrals found in real applications can be computed by closed-form antiderivatives. Others are not so accommodating. Some antiderivatives do not have closed forms, some closed forms require special functions that themselves are a challenge to compute, and others are so complex that finding the exact answer is too slow. This motivates the study and application of numerical approximations of integrals. This subject, called numerical integration or numerical quadrature, arose early in the study of integration for the purpose of making hand calculations. The development of general-purpose computers made numerical integration more practical and drove a desire for improvements. The goals of numerical integration are accuracy, reliability, efficiency, and generality, and sophisticated modern methods can vastly outperform a naive method by all four measures.Consider, for example, the integral

| x | −2.00 | −1.50 | −1.00 | −0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f(x) | 2.22800 | 2.45663 | 2.67200 | 2.32475 | 0.64400 | −0.92575 | −0.94000 | −0.16963 | 0.83600 | |||||||||

| x | −1.75 | −1.25 | −0.75 | −0.25 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 1.25 | 1.75 | ||||||||||

| f(x) | 2.33041 | 2.58562 | 2.62934 | 1.64019 | −0.32444 | −1.09159 | −0.60387 | 0.31734 | ||||||||||

Numerical quadrature methods: ■ Rectangle, ■ Trapezoid, ■ Romberg, ■ Gauss

Using the left end of each piece, the rectangle method sums 16 function values and multiplies by the step width, h, here 0.25, to get an approximate value of 3.94325 for the integral. The accuracy is not impressive, but calculus formally uses pieces of infinitesimal width, so initially this may seem little cause for concern. Indeed, repeatedly doubling the number of steps eventually produces an approximation of 3.76001. However, 218 pieces are required, a great computational expense for such little accuracy; and a reach for greater accuracy can force steps so small that arithmetic precision becomes an obstacle.

A better approach replaces the rectangles used in a Riemann sum with trapezoids. The trapezoid rule is almost as easy to calculate; it sums all 17 function values, but weights the first and last by one half, and again multiplies by the step width. This immediately improves the approximation to 3.76925, which is noticeably more accurate. Furthermore, only 210 pieces are needed to achieve 3.76000, substantially less computation than the rectangle method for comparable accuracy. The idea behind the trapezoid rule, that more accurate approximations to the function yield better approximations to the integral, can be carried further. Simpson's rule approximates the integrand by a piecewise quadratic function. Riemann sums, the trapezoid rule, and Simpson's rule are examples of a family of quadrature rules called Newton–Cotes formulas. The degree n Newton–Cotes quadrature rule approximates the polynomial on each subinterval by a degree n polynomial. This polynomial is chosen to interpolate the values of the function on the interval. Higher degree Newton-Cotes approximations can be more accurate, but they require more function evaluations (already Simpson's rule requires twice the function evaluations of the trapezoid rule), and they can suffer from numerical inaccuracy due to Runge's phenomenon. One solution to this problem is Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature, in which the integrand is approximated by expanding it in terms of Chebyshev polynomials. This produces an approximation whose values never deviate far from those of the original function.

Romberg's method builds on the trapezoid method to great effect. First, the step lengths are halved incrementally, giving trapezoid approximations denoted by T(h0), T(h1), and so on, where hk+1 is half of hk. For each new step size, only half the new function values need to be computed; the others carry over from the previous size (as shown in the table above). But the really powerful idea is to interpolate a polynomial through the approximations, and extrapolate to T(0). With this method a numerically exact answer here requires only four pieces (five function values). The Lagrange polynomial interpolating {hk,T(hk)}k = 0...2 = {(4.00,6.128), (2.00,4.352), (1.00,3.908)} is 3.76 + 0.148h2, producing the extrapolated value 3.76 at h = 0.

Gaussian quadrature often requires noticeably less work for superior accuracy. In this example, it can compute the function values at just two x positions, ±2 ⁄ √3, then double each value and sum to get the numerically exact answer. The explanation for this dramatic success lies in the choice of points. Unlike Newton–Cotes rules, which interpolate the integrand at evenly spaced points, Gaussian quadrature evaluates the function at the roots of a set of orthogonal polynomials. An n-point Gaussian method is exact for polynomials of degree up to 2n − 1. The function in this example is a degree 3 polynomial, plus a term that cancels because the chosen endpoints are symmetric around zero. (Cancellation also benefits the Romberg method.)

In practice, each method must use extra evaluations to ensure an error bound on an unknown function; this tends to offset some of the advantage of the pure Gaussian method, and motivates the popular Gauss–Kronrod quadrature formulae. More broadly, adaptive quadrature partitions a range into pieces based on function properties, so that data points are concentrated where they are needed most.

The computation of higher-dimensional integrals (for example, volume calculations) makes important use of such alternatives as Monte Carlo integration.

A calculus text is no substitute for numerical analysis, but the reverse is also true. Even the best adaptive numerical code sometimes requires a user to help with the more demanding integrals. For example, improper integrals may require a change of variable or methods that can avoid infinite function values, and known properties like symmetry and periodicity may provide critical leverage. For example, the integral

is difficult to evaluate numerically because it is infinite at x = 0. However, the substitution u = √x transforms the integral into

is difficult to evaluate numerically because it is infinite at x = 0. However, the substitution u = √x transforms the integral into  , which has no singularities at all.

, which has no singularities at all.

![{\displaystyle \int _{a}^{b}f(x)dx=\left[F(x)\right]_{a}^{b}=F(b)-F(a)\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/432bdab4e0ff056495611f87fd2b28ba49098d86)

![\int _{a}^{b}\left[\int _{c}^{d}f(x,y)\,dy\right]\,dx.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/256270a484958e5779a7620acb794e26ee9fde16)

![{\displaystyle f:[a,b]\to \mathbb {R} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b592d102ccd1ba134d401c5b3ea177baaba3ffac)