Apollo 12 lunar module Intrepid prepares to descend towards the surface of the Moon. NASA photo.

The physical exploration of the Moon began when Luna 2, a space probe launched by the Soviet Union, made an impact on the surface of the Moon

on September 14, 1959. Prior to that the only available means of

exploration had been observation from Earth. The invention of the optical telescope brought about the first leap in the quality of lunar observations. Galileo Galilei

is generally credited as the first person to use a telescope for

astronomical purposes; having made his own telescope in 1609, the

mountains and craters on the lunar surface were among his first observations using it.

NASA's Apollo program was the first, and to date only, mission to successfully land humans on the Moon, which it did six times. The first landing took place in 1969, when astronauts placed scientific instruments and returned lunar samples to Earth.

Early history

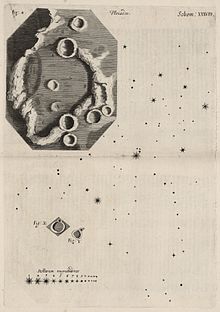

A study of the Moon from Robert Hooke's Micrographia, 1665

The ancient Greek philosopher Anaxagoras

(d. 428 BC) reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical

rocks, and that the latter reflected the light of the former. His

non-religious view of the heavens was one cause for his imprisonment and

eventual exile. In his little book On the Face in the Moon's Orb, Plutarch

suggested that the Moon had deep recesses in which the light of the Sun

did not reach and that the spots are nothing but the shadows of rivers

or deep chasms. He also entertained the possibility that the Moon was

inhabited.

Aristarchus went a step further and computed the distance from Earth, together with its size, obtaining a value of 20 times the Earth radius for the distance (the real value is 60; the Earth radius was roughly known since Eratosthenes).

Although the Chinese of the Han Dynasty (202 BC–202 AD) believed the Moon to be energy equated to qi,

their 'radiating influence' theory recognized that the light of the

Moon was merely a reflection of the Sun (mentioned by Anaxagoras above). This was supported by mainstream thinkers such as Jing Fang, who noted the sphericity of the Moon. Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song Dynasty

(960–1279) created an allegory equating the waxing and waning of the

Moon to a round ball of reflective silver that, when doused with white

powder and viewed from the side, would appear to be a crescent.

By 499 AD, the Indian astronomer Aryabhata mentioned in his Aryabhatiya that reflected sunlight is the cause behind the shining of the Moon.

The earliest surviving daguerrotype of the Moon by John W. Draper (1840)

Photo of the Moon made by Lewis Rutherfurd in 1865

Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi, a Persian astronomer, conducted various observations at the Al-Shammisiyyah observatory in Baghdad between 825 and 835 AD.

Using these observations, he estimated the Moon's diameter as 3,037 km

(equivalent to 1,519 km radius) and its distance from the Earth as

346,345 km (215,209 mi), which come close to the currently accepted

values. In the 11th century, the Islamic physicist, Alhazen, investigated moonlight, which he proved through experimentation originates from sunlight and correctly concluded that it "emits light from those portions of its surface which the sun's light strikes."

By the Middle Ages,

before the invention of the telescope, an increasing number of people

began to recognise the Moon as a sphere, though many believed that it

was "perfectly smooth". In 1609, Galileo Galilei drew one of the first telescopic drawings of the Moon in his book Sidereus Nuncius and noted that it was not smooth but had mountains and craters. Later in the 17th century, Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Francesco Maria Grimaldi

drew a map of the Moon and gave many craters the names they still have

today. On maps, the dark parts of the Moon's surface were called maria (singular mare) or seas, and the light parts were called terrae or continents.

Thomas Harriot,

as well as Galilei, drew the first telescopic representation of the

Moon and observed it for several years. His drawings, however, remained

unpublished. The first map of the Moon was made by the Belgian cosmographer and astronomer Michael Florent van Langren in 1645. Two years later a much more influential effort was published by Johannes Hevelius. In 1647 Hevelius published Selenographia, the first treatise entirely devoted to the Moon. Hevelius's nomenclature, although used in Protestant countries until the eighteenth century, was replaced by the system published in 1651 by the Jesuit astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli,

who gave the large naked-eye spots the names of seas and the telescopic

spots (now called craters) the name of philosophers and astronomers. In 1753 the Croatian Jesuit and astronomer Roger Joseph Boscovich discovered the absence of atmosphere on the Moon. In 1824 Franz von Gruithuisen explained the formation of craters as a result of meteorite strikes.

The possibility that the Moon contains vegetation and is

inhabited by selenites was seriously considered by major astronomers

even into the first decades of the 19th century. In 1834–1836, Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler published their four-volume Mappa Selenographica and the book Der Mond in 1837, which firmly established the conclusion that the Moon has no bodies of water nor any appreciable atmosphere.

Space race

The Cold War-inspired "space race" and "Moon race" between the Soviet Union and the United States of America

accelerated with a focus on the Moon. This included many scientifically

important firsts, such as the first photographs of the then-unseen far side of the Moon

in 1959 by the Soviet Union, and culminated with the landing of the

first humans on the Moon in 1969, widely seen around the world as one of

the pivotal events of the 20th century, and indeed of human history in

general.

The first image returned of another world from space, photographed by Luna 3, showed the Moon's far side.

Luna 9 was the first spacecraft to achieve a landing on the Moon.

The first man-made object to reach the Moon was the unmanned Soviet probe Luna 2,

which made a hard landing on September 14, 1959, at 21:02:24 Z. The far

side of the Moon was first photographed on October 7, 1959, by the

Soviet probe Luna 3. Though vague by today's standards, the photos showed that the far side of the Moon almost completely lacked maria. In an effort to compete with these Soviet successes, U.S. President John F. Kennedy proposed the national goal of landing a human on the Moon. Speaking to a Joint Session of Congress on May 25, 1961, he said

First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space.

The Soviets nonetheless remained in the lead for some time. Luna 9

was the first probe to soft land on the Moon and transmit pictures from

the lunar surface on February 3, 1966. It was proven that a lunar

lander would not sink into a thick layer of dust, as had been feared.

The first artificial satellite of the Moon was the Soviet probe Luna 10, launched March 31, 1966.

Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt standing next to a boulder at Taurus-Littrow during the third EVA (extravehicular activity). NASA photo.

On December 24, 1968, the crew of Apollo 8, Frank Borman, James Lovell and William Anders,

became the first human beings to enter lunar orbit and see the far side

of the Moon in person. Humans first landed on the Moon on July 20,

1969. The first human to walk on the lunar surface was Neil Armstrong, commander of the U.S. mission Apollo 11. The first robot lunar rover to land on the Moon was the Soviet vessel Lunokhod 1 on November 17, 1970, as part of the Lunokhod programme. To date, the last human to stand on the Moon was Eugene Cernan, who as part of the mission Apollo 17, walked on the Moon in December 1972.

Moon rock samples were brought back to Earth by three Luna missions (Luna 16, 20, and 24) and the Apollo missions 11 through 17 (except Apollo 13, which aborted its planned lunar landing).

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s there were 65 Moon landings (with 10 in 1971 alone), but after Luna 24 in 1976 they suddenly stopped. The Soviet Union started focusing on Venus and space stations and the U.S. on Mars and beyond, and on the Skylab and Space Shuttle programs.

Before the Moon race the US had pre-projects for scientific and military moonbases: the Lunex Project and Project Horizon. Besides manned landings, the abandoned Soviet manned lunar programs included the building of a multipurpose moonbase "Zvezda", the first detailed project, complete with developed mockups of expedition vehicles and surface modules.

Recent exploration

Cassini–Huygens took this image during its lunar flyby, before it traveled to Saturn

In 1990 Japan visited the Moon with the Hiten spacecraft, becoming the third country to place an object in orbit around the Moon. The spacecraft released the Hagoromo

probe into lunar orbit, but the transmitter failed, thereby preventing

further scientific use of the spacecraft. In September 2007, Japan

launched the SELENE

spacecraft, with the objectives "to obtain scientific data of the lunar

origin and evolution and to develop the technology for the future lunar

exploration", according to the JAXA official website.

The European Space Agency launched a small, low-cost lunar orbital probe called SMART 1 on September 27, 2003. SMART 1's primary goal was to take three-dimensional X-ray and infrared imagery of the lunar surface. SMART 1 entered lunar orbit

on November 15, 2004 and continued to make observations until September

3, 2006, when it was intentionally crashed into the lunar surface in

order to study the impact plume.

China has begun the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program for exploring the Moon and is investigating the prospect of lunar mining, specifically looking for the isotope helium-3 for use as an energy source on Earth. China launched the Chang'e 1 robotic lunar orbiter

on October 24, 2007. Originally planned for a one-year mission, the

Chang'e 1 mission was very successful and ended up being extended for

another four months. On March 1, 2009, Chang'e 1 was intentionally

impacted on the lunar surface completing the 16-month mission. On

October 1, 2010, China launched the Chang'e 2 lunar orbiter. China landed the rover Chang'e 3 on the Moon on December 14, 2013, became the third country to have done so. Chang'e 3 is the first spacecraft to soft-land on lunar surface since Luna 24 in 1976.

India's national space agency, Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), launched Chandrayaan-1, an unmanned lunar orbiter, on October 22, 2008.[16]

The lunar probe was originally intended to orbit the Moon for two

years, with scientific objectives to prepare a three-dimensional atlas

of the near and far side of the Moon and to conduct a chemical and

mineralogical mapping of the lunar surface. The unmanned Moon Impact Probe landed on the Moon at 15:04 GMT on November 14, 2008 making India the fourth country to touch down on the lunar surface.

Among its many achievements was the discovery of the widespread presence

of water molecules in lunar soil.

Animation of Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter's trajectory from 23 June 2009 to 30 June 2009

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter · Moon

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter · Moon

The Ballistic Missile Defense Organization and NASA launched the Clementine mission in 1994, and Lunar Prospector in 1998. NASA launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter,

on June 18, 2009, which has collected imagery of the Moon's surface. It

also carried the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), which investigated the possible existence of water in Cabeus crater. GRAIL is another mission, launched in 2011.

The first commercial mission to the Moon was accomplished by the Manfred Memorial Moon Mission (4M), led by LuxSpace, an affiliate of German OHB AG. The mission was launched on 23 October 2014 with the Chinese Chang'e 5-T1 test spacecraft, attached to the upper stage of a Long March 3C/G2 rocket.

The 4M spacecraft made a Moon flyby on a night of 28 October 2014,

after which it entered elliptical Earth orbit, exceeding its designed

lifetime by four times.

Plans

Following the abandoned US Constellation program, plans for manned flights followed by moonbases were declared by Russia, Europe (ESA), China, Japan and India. All of them intend to continue the exploration of Moon with more unmanned spacecraft.

China planned to conduct a sample return mission with its Chang'e 5 spacecraft in 2017, but that mission has been postponed until 2019 due to the 2017 failure of the Long March 5 launch vehicle. It will also send Chang'e 4, the backup model of the Chang'e 3 lander) to the lunar farside in 2018.

Since the Chang'e 3 mission was a success, the backup lander Chang'e 4

is re-purposed for the mission to the farside, which will be the first

time it is attempted by any of the space faring countries.

India expects to launch another lunar mission by 2018, the Chandrayaan-2, which would place a motorized rover on the Moon.

Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

plans a manned lunar landing around 2020 that would lead to a manned

lunar base by 2030; however, there is no budget yet for this project and

the plan reverts to robotic missions.

Russia also announced to resume its previously frozen project Luna-Glob, an unmanned lander and orbiter, which is slated to launch in 2016. In 2015, Roscosmos

stated that Russia plans to place an astronaut on the Moon by 2030

leaving Mars to NASA. The purpose is to work jointly with NASA and avoid

a space race.

Germany also announced in March 2007 that it would launch a national lunar orbiter, LEO in 2012. However the mission was cancelled due to budgetary constraints.

In August 2007, NASA stated that all future missions and explorations of the Moon will be done entirely using the metric system. This was done to improve cooperation with space agencies of other countries which already use the metric system.

The European Space Agency has also announced its intention to send a manned mission to the Moon, as part of the Aurora programme. In September 2010, the agency introduced a "Lunar lander" programme with a target of autonomous mission to the Moon in 2018.

On September 13, 2007, the X Prize Foundation, in concert with Google, Inc., announced the Google Lunar X Prize.

This contest requires competitors "to land a privately funded robotic

rover on the Moon that is capable of completing several mission

objectives, including roaming the lunar surface for at least 500 meters

and sending video, images and data back to the Earth."

In March 2014, SpaceX indicated that while their current focus is not on Lunar space transport, they will consider commercial launch contracts for one-off Moon missions.

Russian Federation spacecraft is planned to send cosmonauts to the moon orbit in 2025. Russian Lunar Orbital Station is then proposed to orbit around the Moon after 2030.