From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

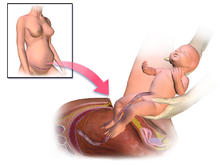

Caesarean section, also known as

C-section, or

caesarean delivery, is the use of

surgery to

deliver babies. A caesarean section is often necessary when a

vaginal delivery would put the baby or mother at risk. This may include

obstructed labor,

twin pregnancy,

high blood pressure in the mother,

breech birth, or problems with the

placenta or

umbilical cord. A caesarean delivery may be performed based upon the shape of the mother's

pelvis or history of a previous C-section. A trial of

vaginal birth after C-section may be possible. The

World Health Organization recommends that caesarean section be performed only when medically necessary. Some C-sections are performed

without a medical reason, upon request by someone, usually the mother.

A C-section typically takes 45 minutes to an hour. It may be done with a

spinal block, where the woman is awake or under

general anesthesia. A

urinary catheter is used to drain the

bladder, and the skin of the

abdomen is then cleaned with an

antiseptic. An

incision of about 15 cm (6 inches) is then typically made through the mother's lower abdomen. The

uterus is then opened with a second incision and the baby delivered. The incisions are then

stitched closed. A woman can typically begin

breastfeeding as soon as she is out of the

operating room and awake. Often, several days are required in the hospital to recover sufficiently to return home.

C-sections result in a small overall increase in poor outcomes in low-risk pregnancies. They also typically take longer to heal from, about six weeks, than vaginal birth. The increased risks include breathing problems in the baby and

amniotic fluid embolism and

postpartum bleeding in the mother. Established guidelines recommend that caesarean sections not be used before 39

weeks of pregnancy without a medical reason. The method of delivery does not appear to have an effect on subsequent

sexual function.

In 2012, about 23 million C-sections were done globally. The international healthcare community has previously considered the rate of 10% and 15% to be ideal for caesarean sections. Some evidence finds a higher rate of 19% may result in better outcomes. More than 45 countries globally have C-section rates less than 7.5%, while more than 50 have rates greater than 27%. Efforts are being made to both improve access to and reduce the use of C-section. In the United States as of 2017, about 32% of deliveries are by C-section.

The surgery has been performed at least as far back as 715 BC following

the death of the mother, with the baby occasionally surviving. Descriptions of mothers surviving date back to 1500. With the introduction of

antiseptics and

anesthetics in the 19th century, survival of both the mother and baby became common.

Uses

A 7-week old caesarean section scar and linea nigra visible on a 31-year-old mother: Longitudinal incisions are still sometimes used.

Caesarean section is recommended when

vaginal delivery might pose a risk to the mother or baby. C-sections are also carried out for personal and social reasons on

maternal request in some countries.

Medical uses

Complications of labor and factors increasing the risk associated with vaginal delivery include:

Other complications of pregnancy, pre-existing conditions, and concomitant disease, include:

Other

- Decreasing experience of accoucheurs with the management of

breech presentation. Although obstetricians and midwives are extensively

trained in proper procedures for breech presentation deliveries using

simulation mannequins, there is decreasing experience with actual

vaginal breech delivery, which may increase the risk.

Prevention

The

prevalence of caesarean section is generally agreed to be higher than

needed in many countries, and physicians are encouraged to actively

lower the rate, as a caesarean rate higher than 10-15% is not associated

with reductions in maternal or infant mortality rates. Some evidence supports a higher rate of 19% may result in better outcomes.

Some of these efforts are: emphasizing a long

latent phase

of labor is not abnormal and not a justification for C-section; a new

definition of the start of active labor from a cervical dilatation of

4 cm to a dilatation of 6 cm; and allowing women who have previously

given birth to push for at least 2 hours, with 3 hours of pushing for

women who have not previously given birth, before

labor arrest is considered.

Physical exercise during pregnancy decreases the risk.

Risks

Adverse outcomes in low-risk pregnancies occur in 8.6% of vaginal deliveries and 9.2% of caesarean section deliveries.

Mother

In those who are low risk, the

risk of death for caesarean sections is 13 per 100,000 vs. for vaginal birth 3.5 per 100,000 in the developed world—a numerically very small risk of death in either situation in resource-rich settings. The United Kingdom

National Health Service gives the risk of death for the mother as three times that of a vaginal birth.

In Canada, the difference in serious morbidity or mortality for

the mother (e.g. cardiac arrest, wound hematoma, or hysterectomy) was

1.8 additional cases per 100. The difference in in-hospital maternal death was not significant.

A caesarean section is associated with risks of postoperative

adhesions, incisional hernias (which may require surgical correction), and wound infections.

If a caesarean is performed in an emergency, the risk of the surgery

may be increased due to a number of factors. The patient's stomach may

not be empty, increasing the risk of anaesthesia. Other risks include severe blood loss (which may require a blood transfusion) and

postdural-puncture spinal headaches.

Wound infections occur after caesarean sections at a rate of 3-15%.

Women who had caesarean sections are more likely to have problems

with later pregnancies, and women who want larger families should not

seek an elective caesarean unless medical indications to do so exist.

The risk of

placenta accreta,

a potentially life-threatening condition which is more likely to

develop where a woman has had a previous caesarean section, is 0.13%

after two caesarean sections, but increases to 2.13% after four and then

to 6.74% after six or more. Along with this is a similar rise in the

risk of emergency hysterectomies at delivery.

Mothers can experience an increased incidence of

postnatal depression, and can experience significant psychological trauma and ongoing

birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder after obstetric intervention during the birthing process.

Factors like pain in the first stage of labor, feelings of

powerlessness, intrusive emergency obstetric intervention are important

in the subsequent development of psychological issues related to labor

and delivery.

Subsequent pregnancies

Women who have had a caesarean for any reason are somewhat less

likely to become pregnant again as compared to women who have previously

delivered only vaginally, but the effect is small.

- Vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC)

- Elective repeat caesarean section (ERCS)

Both have higher risks than a vaginal birth with no previous

caesarean section. There are many issues which must be taken into

account when planning the mode of delivery for every pregnancy, not just

those complicated by a previous caesarean section and there is a list

of some of these issues in the list of indications for section in the

first part of this article. A vaginal birth after caesarean section

(VBAC) confers a higher risk of

uterine rupture (5 per 1,000), blood transfusion or

endometritis (10 per 1,000), and

perinatal death of the child (0.25 per 1,000).

Furthermore, 20% to 40% of planned VBAC attempts end in caesarean

section being needed, with greater risks of complications in an

emergency repeat caesarean section than in an elective repeat caesarean

section. On the other hand, VBAC confers less

maternal morbidity and a decreased risk of complications in future pregnancies than elective repeat caesarean section.

Adhesions

Suturing of the uterus after extraction

Closed incision for low transverse abdominal incision after stapling has been completed

There are several steps that can be taken during abdominal or pelvic

surgery to minimize postoperative complications, such as the formation

of

adhesions. Such techniques and principles may include:

- • Handling all tissue with absolute care

- • Using powder-free surgical gloves

- • Controlling bleeding

- • Choosing sutures and implants carefully

- • Keeping tissue moist

- • Preventing infection with antibiotics given intravenously to the mother before skin incision

Despite these proactive measures, adhesion formation is a recognized

complication of any abdominal or pelvic surgery. To prevent adhesions

from forming after caesarean section,

adhesion barrier

can be placed during surgery to minimize the risk of adhesions between

the uterus and ovaries, the small bowel, and almost any tissue in the

abdomen or pelvis. This is not current UK practice, as there is no

compelling evidence to support the benefit of this intervention.

Adhesions can cause long-term problems, such as:

- • Infertility,

which may end when adhesions distort the tissues of the ovaries and

tubes, impeding the normal passage of the egg (ovum) from the ovary to

the uterus. One in five infertility cases may be adhesion related

(stoval)

- • Chronic pelvic pain, which may result when adhesions are present

in the pelvis. Almost 50% of chronic pelvic pain cases are estimated to

be adhesion related (stoval)

- • Small bowel obstruction: the disruption of normal bowel flow, which can result when adhesions twist or pull the small bowel.

The risk of adhesion formation is one reason why vaginal delivery is

usually considered safer than elective caesarean section where there is

no medical indication for section for either maternal or fetal reasons.

Child

Non-medically

indicated (elective) childbirth before 39 weeks gestation "carry

significant risks for the baby with no known benefit to the mother."

Complications from elective caesarean before 39 weeks include: newborn

mortality at 37 weeks may be up to 3 times the number at 40 weeks, and

was elevated compared to 38 weeks gestation. These “early term” births

were associated with more death during infancy, compared to those

occurring at 39 to 41 weeks ("full term").

Researchers in one study and another review found many benefits to

going full term, but “no adverse effects” in the health of the mothers

or babies.

The

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and medical policy makers review research studies and find more incidence of suspected or proven

sepsis,

RDS, hypoglycemia, need for respiratory support, need for NICU

admission, and need for hospitalization > 4–5 days. In the case of

caesarean sections, rates of respiratory death were 14 times higher in

pre-labor at 37 compared with 40 weeks gestation, and 8.2 times higher

for pre-labor caesarean at 38 weeks. In this review, no studies found

decreased neonatal morbidity due to non-medically indicated (elective)

delivery before 39 weeks.

For otherwise healthy

twin pregnancies where both twins are head down a trial of

vaginal delivery is recommended at between 37 and 38 weeks. Vaginal delivery, in this case, does not worsen the outcome for either infant as compared with caesarean section.

There is some controversy on the best method of delivery where the

first twin is head first and the second is not, but most obstetricians

will recommend normal delivery unless there are other reasons to avoid

vaginal birth. When the first twin is not head down, a caesarean section is often recommended.

Regardless of whether the twins are delivered by section or vaginally,

the medical literature recommends delivery of dichorionic twins at 38

weeks, and monochorionic twins (identical twins sharing a placenta) by

37 weeks due to the increased risk of stillbirth in monochorionic twins

who remain in utero after 37 weeks.

The consensus is that late preterm delivery of monochorionic twins is

justified because the risk of stillbirth for post-37 week delivery is

significantly higher than the risks posed by delivering monochorionic

twins near term (i.e., 36–37 weeks).

The consensus concerning monoamniotic twins (identical twins sharing an

amniotic sac), the highest risk type of twins, is that they should be

delivered by caesarean section at or shortly after 32 weeks, since the

risks of intrauterine death of one or both twins is higher after this

gestation than the risk of complications of prematurity.

In a research study widely publicized, singleton children born

earlier than 39 weeks may have developmental problems, including slower

learning in reading and math.

Other risks include:

- Wet lung: Retention of fluid in the lungs can occur if not expelled by the pressure of contractions during labor.

- Potential for early delivery and complications: Preterm delivery may

be inadvertently carried out if the due-date calculation is inaccurate.

One study found an increased complication risk if a repeat elective

caesarean section is performed even a few days before the recommended 39

weeks.

- Higher infant mortality risk: In caesarean sections performed with

no indicated medical risk (singleton at full term in a head-down

position with no other obstetric or medical complications), the risk of

death in the first 28 days of life has been cited as 1.77 per 1,000 live

births among women who had caesarean sections, compared to 0.62 per

1,000 for women who delivered vaginally.

Birth by caesarean section also seems to be associated with worse

health outcomes later in life, including overweight or obesity and

problems in the immune system.

Classification

Caesarean sections have been classified in various ways by different perspectives.

One way to discuss all classification systems is to group them by their

focus either on the urgency of the procedure, characteristics of the

mother, or as a group based on other, less commonly discussed factors.

It is most common to classify caesarean sections by the urgency of performing them.

By urgency

Conventionally, caesarean sections are classified as being either an

elective surgery or an

emergency operation.

Classification is used to help communication between the obstetric,

midwifery and anaesthetic team for discussion of the most appropriate

method of anaesthesia. The decision whether to perform

general anesthesia or

regional anesthesia

(spinal or epidural anaesthetic) is important and is based on many

indications, including how urgent the delivery needs to be as well as

the medical and obstetric history of the woman.

Regional anaesthetic is almost always safer for the woman and the baby

but sometimes general anaesthetic is safer for one or both, and the

classification of urgency of the delivery is an important issue

affecting this decision.

A planned caesarean (or elective/scheduled caesarean), arranged

ahead of time, is most commonly arranged for medical indications which

have developed before or during the pregnancy, and ideally after 39

weeks of gestation. In the UK, this is classified as a 'grade 4' section

(delivery timed to suit the mother or hospital staff) or as a 'grade 3'

section (no maternal or fetal compromise but early delivery needed).

Emergency caesarean sections are performed in pregnancies in which a

vaginal delivery was planned initially, but an indication for caesarean

delivery has since developed. In the UK they are further classified as

grade 2 (delivery required within 90 minutes of the decision but no

immediate threat to the life of the woman or the fetus) or grade 1

(delivery required within 30 minutes of the decision: immediate threat

to the life of the mother or the baby or both.)

Elective caesarean sections may be performed on the basis of an

obstetrical or medical indication, or because of a medically

non-indicated

maternal request. Among women in the United Kingdom, Sweden and Australia, about 7% preferred caesarean section as a method of delivery. In cases without medical indications the

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommend a planned vaginal delivery. The

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

recommends that if after a woman has been provided information on the

risk of a planned caesarean section and she still insists on the

procedure it should be provided. If provided this should be done at 39 weeks of gestation or later. There is no evidence that ECS can reduce mother-to-child

hepatitis B and

hepatitis C virus transmission.

By characteristics of the mother

Caesarean delivery on maternal request

Caesarean delivery on maternal request (CDMR) is a medically unnecessary caesarean section, where the conduct of a

childbirth via a caesarean section is requested by the

pregnant patient even though there is not a medical

indication to have the surgery. Systematic reviews have found no strong evidence about the impact of caesareans for nonmedical reasons.

Recommendations encourage counseling to identify the reasons for the

request, addressing anxieties and information, and encouraging vaginal

birth. Elective caesareans at 38 weeks in some studies showed increased health complications in the newborn. For this reason

ACOG and

NICE recommend that elective caesarean sections should not be scheduled before 39 weeks gestation unless there is a medical reason.

Planned caesarean sections may be scheduled earlier if there is a medical reason.

After previous caesarean

Mothers who have previously had a caesarean section are more likely

to have a caesarean section for future pregnancies than mothers who have

never had a caesarean section. There is discussion about the

circumstances under which women should have a vaginal birth after a

previous caesarean.

Vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) is the practice of

birthing a baby vaginally after a previous baby has been delivered by caesarean section (surgically). According to

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

(ACOG), successful VBAC is associated with decreased maternal morbidity

and a decreased risk of complications in future pregnancies. According to the American Pregnancy Association, 90% of women who have undergone caesarean deliveries are candidates for VBAC.

Approximately 60-80% of women opting for VBAC will successfully give

birth vaginally, which is comparable to the overall vaginal delivery

rate in the United States in 2010.

Twins

For

otherwise healthy twin pregnancies where both twins are head down a

trial of vaginal delivery is recommended at between 37 and 38 weeks. Vaginal delivery in this case does not worsen the outcome for either infant as compared with caesarean section. There is controversy on the best method of delivery where the first twin is head first and the second is not. When the first twin is not head down at the point of labor starting, a caesarean section should be recommended.

Although the second twin typically has a higher frequency of problems,

it is not known if a planned caesarean section affects this. It is estimated that 75% of twin pregnancies in the United States were delivered by caesarean section in 2008.

Breech birth

A breech birth is the birth of a baby from a breech

presentation, in which the baby exits the pelvis with the

buttocks or

feet first as opposed to the normal

head-first presentation. In breech presentation, fetal heart sounds are heard just above the umbilicus.

Babies are usually born head first. If the baby is in another

position the birth may be complicated. In a ‘breech presentation’, the

unborn baby is bottom-down instead of head-down. Babies born

bottom-first are more likely to be harmed during a normal (vaginal)

birth than those born head-first. For instance, the baby might not get

enough oxygen during the birth. Having a planned caesarean may reduce

these problems. A review looking at planned caesarean section for

singleton breech presentation with planned vaginal birth, concludes that

in the short term, births with a planned caesarean were safer for

babies than vaginal births. Fewer babies died or were seriously hurt

when they were born by caesarean. There was tentative evidence that

children who were born by caesarean had more health problems at age two.

Caesareans caused some short-term problems for mothers such as more

abdominal pain. They also had some benefits, such as less urinary

incontinence and less perineal pain.

The bottom-down position presents some hazards to the baby during

the process of birth, and the mode of delivery (vaginal versus

caesarean) is controversial in the fields of

obstetrics and

midwifery.

Though vaginal

birth

is possible for the breech baby, certain fetal and maternal factors

influence the safety of vaginal breech birth. The majority of breech

babies born in the United States and the UK are delivered by caesarean

section as studies have shown increased risks of morbidity and mortality

for vaginal breech delivery, and most obstetricians counsel against

planned vaginal breech birth for this reason. As a result of reduced

numbers of actual vaginal breech deliveries, obstetricians and midwives

are at risk of de-skilling in this important skill. All those involved

in delivery of obstetric and midwifery care in the UK undergo mandatory

training in conducting breech deliveries in the simulation environment

(using dummy pelvises and mannequins to allow practice of this important

skill) and this training is carried out regularly to keep skills up to

date.

Resuscitative hysterotomy

A resuscitative

hysterotomy, also known as a peri-mortem caesarean delivery, is an emergency caesarean delivery carried out where maternal

cardiac arrest has occurred, to assist in

resuscitation of the mother by removing the

aortocaval compression

generated by the gravid uterus. Unlike other forms of caesarean

section, the welfare of the fetus is a secondary priority only, and the

procedure may be performed even prior to the limit of

fetal viability if it is judged to be of benefit to the mother.

Other ways, including the surgery technique

There

are several types of caesarean section (CS). An important distinction

lies in the type of incision (longitudinal or transverse) made on the

uterus, apart from the incision on the skin: the vast majority of skin incisions are a transverse suprapubic approach known as a

Pfannenstiel incision but there is no way of knowing from the skin scar which way the uterine incision was conducted.

- The classical caesarean section involves a longitudinal

midline incision on the uterus which allows a larger space to deliver

the baby. It is performed at very early gestations where the lower

segment of the uterus is unformed as it is safer in this situation for

the baby: but it is rarely performed other than at these early

gestations, as the operation is more prone to complications than a low

transverse uterine incision. Any woman who has had a classical section

will be recommended to have an elective repeat section in subsequent

pregnancies as the vertical incision is much more likely to rupture in

labor than the transverse incision.

- The lower uterine segment section is the procedure most commonly used today; it involves a transverse cut just above the edge of the bladder. It results in less blood loss

and has fewer early and late complications for the mother, as well as

allowing her to consider a vaginal birth in the next pregnancy.

- A caesarean hysterectomy consists of a caesarean section followed by the removal of the uterus. This may be done in cases of intractable bleeding or when the placenta cannot be separated from the uterus.

The

EXIT procedure is a specialized surgical delivery procedure used to deliver babies who have airway compression.

The Misgav Ladach method is a modified caesarean section which

has been used nearly all over the world since the 1990s. It was

described by Michael Stark, the president of the New European Surgical

Academy, at the time he was the director of

Misgav Ladach, a general hospital in Jerusalem. The method was presented during a FIGO conference in Montréal in 1994

and then distributed by the University of Uppsala, Sweden, in more than

100 countries. This method is based on minimalistic principles. He

examined all steps in caesarean sections in use, analyzed them for their

necessity and, if found necessary, for their optimal way of

performance. For the abdominal incision he used the modified Joel Cohen

incision and compared the longitudinal abdominal structures to strings

on musical instruments. As blood vessels and muscles have lateral sway,

it is possible to stretch rather than cut them. The peritoneum is opened

by repeat stretching, no abdominal swabs are used, the uterus is closed

in one layer with a big needle to reduce the amount of foreign body as

much as possible, the peritoneal layers remain unsutured and the abdomen

is closed with two layers only. Women undergoing this operation recover

quickly and can look after the newborns soon after surgery. There are

many publications showing the advantages over traditional caesarean

section methods. There is also an increased risk of abruptio placentae

and uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies for women who underwent

this method in prior deliveries.

Technique

Several caesarean sections:

Is: supra-umbilical incision

Im: median incision

IM: Maylard incision

IP: Pfannenstiel incision

Illustration depicting caesarean section

Antibiotic prophylaxis is used before an incision. The

uterus is incised, and this incision is extended with blunt pressure along a cephalad-caudad axis. The infant is delivered, and the

placenta is then removed. The surgeon then makes a decision about uterine exteriorization. Single-layer uterine closure is used when the mother does not want a future pregnancy. When subcutaneous tissue is 2 cm thick or more,

surgical suture is used. Discouraged practices include manual

cervical dilation, any subcutaneous

drain, or supplemental

oxygen therapy with intent to prevent infection.

Caesarean section can be performed with

single or

double layer suturing of the uterine incision.

Single layer closure compared with double layer closure has been

observed to result in reduced blood loss during the surgery. It is

uncertain whether this is the direct effect of the suturing technique or

if other factors such as the type and site of abdominal incision

contribute to reduced blood loss. Standard procedure includes the closure of the

peritoneum.

Research questions whether this is needed, with some studies indicating

peritoneal closure is associated with longer operative time and

hospital stay.

The Misgave Ladach method is a surgery technical that may have fewer

secondary complications and faster healing, due to the insertion into

the muscle.

Anesthesia

Both

general and

regional anaesthesia (

spinal,

epidural or

combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia)

are acceptable for use during caesarean section. Evidence does not show

a difference between regional anaesthesia and general anaesthesia with

respect to major outcomes in the mother or baby. Regional anaesthesia may be preferred as it allows the mother to be awake and interact immediately with her baby. Compared to general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia is better at preventing

persistent postoperative pain 3 to 8 months after caesarean section. Other advantages of regional anesthesia may include the absence of typical risks of general anesthesia:

pulmonary aspiration (which has a relatively high incidence in patients undergoing anesthesia in late pregnancy) of gastric contents and

esophageal intubation. One trial found no difference in satisfaction when general anaesthesia was compared with either spinal anaesthesia.

Regional anaesthesia is used in 95% of deliveries, with spinal

and combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia being the most commonly

used regional techniques in scheduled caesarean section. Regional anaesthesia during caesarean section is different from the

analgesia

(pain relief) used in labor and vaginal delivery. The pain that is

experienced because of surgery is greater than that of labor and

therefore requires a more intense

nerve block.

General anesthesia may be necessary because of specific risks to

mother or child. Patients with heavy, uncontrolled bleeding may not

tolerate the hemodynamic effects of regional anesthesia. General

anesthesia is also preferred in very urgent cases, such as severe fetal

distress, when there is no time to perform a regional anesthesia.

Prevention of complications

Postpartum infection is one of the main causes of maternal death and may account for 10% of maternal deaths globally.

A caesarean section greatly increases the risk of infection and

associated morbidity, estimated to be between 5 and 20 times as high,

and routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infections was

found by a

meta-analysis to substantially reduce the incidence of febrile morbidity. Infection can occur in around 8% of women who have caesareans, largely

endometritis,

urinary tract infections

and wound infections. The use of preventative antibiotics in women

undergoing caesarean section decreased wound infection, endometritis,

and serious infectious complications by about 65%. Side effects and effect on the baby is unclear.

Women who have caesareans can recognize the signs of fever that indicate the possibility of wound infection. Taking antibiotics before skin incision rather than after

cord clamping reduces the risk for the mother, without increasing adverse effects for the baby. Whether a particular type of skin cleaner improves outcomes is unclear.

Some doctors believe that during a caesarean section, mechanical

cervical dilation with a finger or forceps will prevent the obstruction of blood and

lochia drainage, and thereby benefit the mother by reducing the risk of death. The evidence as of 2018 neither supported nor refuted this practice for reducing postoperative morbidity, pending further large studies.

Recovery

It is

common for women who undergo caesarean section to have reduced or

absent bowel movements for hours to days. During this time, women may

experience abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting. This usually resolves

without treatment. Poorly controlled pain following non-emergent caesarean section occurs in between 13% to 78% of women. Abdominal, wound and back pain can continue for months after a caesarean section.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful.

For the first couple of weeks after a cesarean, women should avoid

lifting anything heavier than their baby. To minimize pain during

breastfeeding, women should experiment with different breastfeeding

holds including the football hold and side-lying hold. Women who have had a caesarean are more likely to experience pain that

interferes with their usual activities than women who have vaginal

births, although by six months there is generally no longer a

difference. Pain during sexual intercourse is less likely than after vaginal birth; by six months there is no difference.

There may be a somewhat higher incidence of postnatal depression

in the first weeks after childbirth for women who have caesarean

sections, but this difference does not persist. Some women who have had caesarean sections, especially emergency caesareans, experience

post-traumatic stress disorder.

Usage

In Italy, the incidence of caesarean sections is particularly high, although it varies from region to region. In

Campania, 60% of 2008 births reportedly occurred via caesarean sections. In the

Rome region, the mean incidence is around 44%, but can reach as high as 85% in some private clinics.

With nearly 1.3 million stays, caesarean section was one of the

most common procedures performed in U.S. hospitals in 2011. It was the

second-most common procedure performed for people ages 18 to 44 years

old. Caesarean rates in the U.S. have risen considerably since 1996.

The procedure increased 60% from 1996 to 2009. In 2010, the caesarean

delivery rate was 32.8% of all births (a slight decrease from 2009's

high of 32.9% of all births).

A study found that in 2011, women covered by private insurance were 11%

more likely to have a caesarean section delivery than those covered by

Medicaid.

China has been cited as having the highest rates of C-sections in the world at 46% as of 2008.

Studies have shown that continuity of care with a known carer may significantly decrease the rate of caesarean delivery

but there is also research that appears to show that there is no

significant difference in Caesarean rates when comparing midwife

continuity care to conventional fragmented care.

More emergency caesareans—about 66%—are performed during the day rather than the night.

The rate has risen to 46% in

China and to levels of 25% and above in many Asian, European and Latin American countries. The rate has increased in the United States, to 33% of all births in 2012, up from 21% in 1996. Across Europe, there are differences between countries: in Italy the caesarean section rate is 40%, while in the

Nordic countries it is 14%. In Brazil and Iran the caesarean section rate is greater than 40%.

Increasing use

In the United States, C-section rates have increased from just over 20% in 1996 to 33% in 2011. This increase has not resulted in improved outcomes resulting in the position that C-sections may be done too frequently.

The World Health Organization officially withdrew its previous

recommendation of a 15% C-section rate in June 2010. Their official

statement read, "There is no empirical evidence for an optimum

percentage. What matters most is that all women who need caesarean

sections receive them."

Speculation explaining a relationship between birth weight and

maternal pelvis size has been proposed. The explanation, based on

Darwinian-inspired logic, states that since the advent of successful

caesarean birth more mothers with small pelvises and babies with large

birth weights survive. This hypothesis would predict an increased

average birth weight, which has been observed. It is unclear what

component contributes more to this effect; evolution or environment.

Brazil has one of the highest caesarean section rates in the

world, with rates in the public sector of 35–45%, and 80–90% in the

private sector.

Epidemiology

Global rates of caesarean section rates are increasing.

It doubled from 2003 to 2018 to reach 21%, and is increasing annually

by 4%. In southern Africa it is less than 5%; the rate is almost 60% in

some parts of Latin America. In the United Kingdom, in 2008, the rate was 24%. In Ireland the rate was 26.1% in 2009. The Canadian rate was 26% in 2005–2006. Australia has a high caesarean section rate, at 31% in 2007. In the United States the rate of C-section is around 33%, varying from 23% to 40% depending on the state.

One out three women who gave birth in the US delivered by caesarean in

2011. In 2012, close to 23 million C-sections were carried out globally. At one time a rate of 10% to 15% was thought to be ideal; a rate of 19% may result in better outcomes. More than 50 nations have rates greater than 27%. Another 45 countries have rates less than 7.5%. There are efforts to both improve access to and reduce the use of C-section. In the United States about 33% of deliveries are by C-section. The rates in the UK and Australia are 26.5% and 32.3% respectively. In China, the most recent CS rate reported was 41%.

Globally, 1% of all caesarean deliveries are carried out without

medical need. Overall, the caesarean section rate was 25.7% for

2004-2008.

Wound infections occur after caesarean sections at a rate of 3-15%.

Some women are at greater risk for developing a surgical site infection

after delivery. The presence of chorioamnionitis and obesity

predisposes the woman to develop a surgical site infection.

History

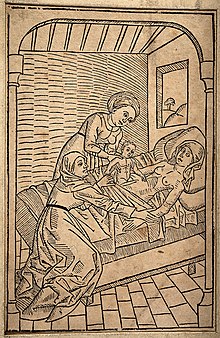

A baby being removed from its dying mother's womb

Caesarean section usually resulted in the death of the mother.

It was long considered an extreme measure, performed only when the

mother was already dead or considered to be beyond help. By way of

comparison, see the

resuscitative hysterotomy or perimortem caesarean section.

The mother of

Bindusara (born c. 320 BC, ruled 298 – c. 272 BC), the second

Mauryan Samrat (

emperor) of India, accidentally consumed poison and died when she was close to delivering him.

Chanakya,

the Chandragupta's teacher and adviser, made up his mind that the baby

should survive. He cut open the belly of the queen and took out the

baby, thus saving the baby's life.

An early account of caesarean section in Iran is mentioned in the book of

Shahnameh, written around 1000 AD, and relates to the birth of

Rostam, the legendary hero of that country. According to the Shahnameh, the

Simurgh instructed

Zal upon how to perform a caesarean section, thus saving

Rudaba and the child Rostam.

The

Babylonian Talmud, an ancient

Jewish religious text, mentions a procedure similar to the caesarean section. The procedure is termed

yotzei dofen. It also discusses at length the permissibility of performing a c-section on a dying or dead mother. There is also some basis for supposing that Jewish women regularly survived the operation in Roman times.

Pliny the Elder

theorized that Julius Caesar's name came from an ancestor who was born

by caesarean section, but the truth of this is debated (see the

discussion of

the etymology of Caesar).

The Ancient Roman caesarean section was first performed to remove a

baby from the womb of a mother who died during childbirth.

The

Catalan saint

Raymond Nonnatus (1204–1240) received his surname—from the

Latin non-natus ("not born")—because he was born by caesarean section. His mother died while giving birth to him.

In an account from the 1580s, in

Siegershausen, Switzerland,

Jakob Nufer a pig gelder, is supposed to have performed the operation on his wife after a prolonged labor, with her surviving. For most of the time since the 16th century, the procedure had a high mortality rate.

In Great Britain and Ireland, the mortality rate in 1865 was 85%. Key steps in reducing mortality were:

A caesarean section performed by indigenous healers in Kahura, Uganda. As observed by medical missionary Robert William Felkin in 1879.

European travelers in the

Great Lakes region of Africa during the 19th century observed caesarean sections being performed on a regular basis.

The expectant mother was normally anesthetized with alcohol, and herbal

mixtures were used to encourage healing. From the well-developed nature

of the procedures employed, European observers concluded they had been

employed for some time.

James Barry was the first European doctor to carry out a successful caesarean in Africa, while posted to Cape Town between 1817 and 1828.

The first successful caesarean section to be performed in the

United States took place in Mason County, Virginia (now Mason County,

West Virginia), in 1794. The procedure was performed by Dr.

Jesse Bennett on his wife Elizabeth.

Caesarius of Terracina

Saint Caesarius of Terracina, invoked for the good success of Caesarean delivery

The patron saint of caesarean section is

Caesarius of Africa, a young deacon martyred at Terracina, who has replaced and Christianized the pagan figure of Caesar. The martyr (Saint Cesareo in Italian) is invoked for the good success of this surgical procedure.

Society and culture

Etymology

Fictional 15th-century depiction of the birth of Julius Caesar

The Roman

Lex Regia (royal law), later the

Lex Caesarea (imperial law), of

Numa Pompilius (715–673 BC), required the child of a mother dead in childbirth to be cut from her

womb.

There was a cultural taboo that mothers should not be buried pregnant, that may have reflected a way of saving some

fetuses.

Roman practice requiring a living mother to be in her tenth month of

pregnancy before resorting to the procedure, reflecting the knowledge

that she could not survive the delivery. Speculation that the Roman dictator

Julius Caesar was born by the method now known as C-section is apparently false. Although caesarean sections were performed in

Roman times, no classical source records a mother surviving such a delivery. As late as the 12th century, scholar and physician

Maimonides expresses doubt over the possibility of a woman's surviving this procedure and again falling pregnant. The term has also been explained as deriving from the verb

caedere, "to cut", with children delivered this way referred to as

caesones.

Pliny the Elder refers to a certain Julius Caesar (an ancestor of the famous Roman statesman) as

ab utero caeso, "cut from the womb" giving this as an explanation for the

cognomen "Caesar" which was then carried by his descendants. Nonetheless, even if the etymological hypothesis linking the caesarean section to Julius Caesar is a

false etymology, it has been widely believed. For example, the

Oxford English Dictionary defines caesarean birth as "the delivery of a child by cutting through the walls of the

abdomen when delivery cannot take place in the natural way, as was done in the case of Julius Caesar".

Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary

(11th edition) leaves room for etymological uncertainty with the

phrase, "from the legendary association of such a delivery with the

Roman cognomen

Caesar".

Some link with Julius Caesar or with Roman emperors exists in other languages as well. For example, the modern

German,

Norwegian,

Danish,

Dutch,

Swedish,

Finnish,

Turkish and

Hungarian terms are respectively

Kaiserschnitt,

keisersnitt,

kejsersnit,

keizersnede,

kejsarsnitt,

keisarinleikkaus,

sezaryen and

császármetszés (literally: "emperor's cut"). The German term has also been imported into

Japanese (帝王切開

teiōsekkai) and

Korean (제왕 절개

jewang jeolgae), both literally meaning "emperor incision". Similarly, in western Slavic (Polish)

cięcie cesarskie, (Czech)

císařský řez and (Slovak)

cisársky rez means "emperor's cut", whereas the south Slavic term is

Serbian царски рез and

Slovenian cárski réz, literally

tzar's cut. The

Russian term

kesarevo secheniye (Кесарево сечение

késarevo sečénije) literally means

Caesar's section. The Arabic term (ولادة قيصرية

wilaada qaySaríyya) also means "caesarean birth." The

Hebrew term ניתוח קיסרי (

nitúakh Keisári) translates literally as caesarean surgery. In Romania and Portugal, it is usually called

cesariana, meaning from (or related to)

Caesar.

Finally, the Roman

praenomen (given name)

Caeso

was said to be given to children who were born via C-section. While

this was probably just folk etymology made popular by Pliny the Elder,

it was well known by the time the term came into common use.

Spelling

The term

caesarean is spelled in various accepted ways,

as discussed at Wiktionary. The

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) of the

United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) uses

cesarean section, while some other American medical works, e.g.

Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary, use

caesarean, as do most British works. The online versions of the US-published

Merriam-Webster Dictionary and

American Heritage Dictionary list

cesarean first and other spellings as "variants", an etymologically anhistorical position.

Presence of father

In many hospitals, the mother's partner is encouraged to attend the surgery to support the mother and share the experience. The

anaesthetist will usually lower the drape temporarily as the child is delivered so the parents can see their newborn.

Special cases

In

Judaism, there is a dispute among the

poskim (Rabbinic authorities) as to whether the first-born son from a caesarean section has the laws of a

bechor. Traditionally, a male child delivered by caesarean is not eligible for the

Pidyon HaBen dedication ritual.

The mother may perform

a caesarean section on herself;

there have been successful cases, such as Inés Ramírez Pérez of Mexico

who, on 5 March 2000, performed a successful caesarean section on

herself. She survived, as did her son, Orlando Ruiz Ramírez.