Headquarters of the Rhenish-Westphalian Coal Syndicate, Germany (at times the best known cartel in the world), around 1910

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collude

with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the

market. Cartels are usually associations in the same sphere of business,

and thus an alliance of rivals. Most jurisdictions consider it

anti-competitive behavior. Cartel behavior includes price fixing, bid rigging, and reductions in output. The doctrine in economics that analyzes cartels is cartel theory. Cartels are distinguished from other forms of collusion or anti-competitive organization such as corporate mergers.

Etymology

The word cartel comes from the Italian word cartello, which means a "leaf of paper" or "placard". The Italian word became cartel in Middle French,

which was borrowed into English. It’s current use in Mexican and

Colombian drug-trafficking world comes from Spanish ‘’cartel’’. In

English, the word was originally used for a written agreement between

warring nations to regulate the treatment and exchange of prisoners.

History

Cartels have existed since ancient times. Guilds in the European Middle Ages, associations of craftsmen or merchants of the same trade, have been regarded as cartel-like. Tightly organized sales cartels in the mining industry of the late Middle Ages, like the 1301 salt syndicate in France and Naples, or the Alaun cartel of 1470 between the Papal State and Naples. Both unions had common sales organizations for overall production called the Societas Communis Vendicionis [Common Sales Society].

Laissez-faire

(liberal) economic conditions dominated Europe and North America in the

18th and 19th centuries. Around 1870, cartels first appeared in

industries formerly under free-market conditions.

Although cartels existed in all economically developed countries, the

core area of cartel activities was in central Europe. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary were nicknamed the "lands of the cartels". Cartels were also widespread in the United States during the period of robber barons and industrial trusts.

The creation of cartels increased globally after World War I. They became the leading form of market organization, particularly in Europe and Japan. In the 1930s, authoritarian regimes such as Nazi Germany, Italy under Mussolini, and Spain under Franco used cartels to organize their planned economies.

Between the late 19th century and around 1945, the United States was

ambivalent about cartels and trusts. There were periods of both

opposition to market concentration and relative tolerance of cartels. During World War II, the United States strictly turned away from cartels. After 1945, American-promoted market liberalism led to a worldwide cartel ban, where cartels continue to be obstructed in an increasing number of countries and circumstances.

Types

Cartels have many structures and functions. Typologies have emerged to distinguish distinct forms of cartels:

- Selling or buying cartels unite against the cartel's customers or suppliers, respectively. The former type is more frequent than the latter.

- Domestic cartels only have members from one country, whereas international cartels have members from more than one country. There have been full-fledged international cartels that have comprised the whole world, such as the international steel cartel of the period between World War I and II.

- Price cartels engage in price fixing, normally to raise prices for a commodity above the competitive price level. The loosest form of a price cartel can be recognized in tacit collusion, wherein smaller enterprises follow the actions of a market leader.

- Quota cartels distribute proportional shares of the market to their members.

- Common sales cartels sell their joint output through a central selling agency (in French: comptoir). They are also known as syndicates (French: syndicat industriel).

- Territorial cartels distribute districts of the market to be used only by individual participants, which act as monopolists.

- Submission cartels control offers given to public tenders. They use bid rigging: bidders for a tender agree on a bid price. They then do not bid in unison, or share the return from the winning bid among themselves.

- Technology and patent cartels share knowledge about technology or science within themselves while they limit the information from outside individuals.

- Condition cartels unify contractual terms – the modes of payment and delivery, or warranty limits.

- Standardization cartels implement common standards for sold or purchased products. If the members of a cartel produce different sorts or grades of a good, conversion factors are applied to calculate the value of the respective output.

- Compulsory cartels, also called "forced cartels", are established or maintained by external pressure. Voluntary cartels are formed by the free will of their participants.

Effects

A

survey of hundreds of published economic studies and legal decisions of

antitrust authorities found that the median price increase achieved by

cartels in the last 200 years is about 23 percent. Private international

cartels (those with participants from two or more nations) had an

average price increase of 28 percent, whereas domestic cartels averaged

18 percent. Less than 10 percent of all cartels in the sample failed to

raise market prices.

In general, cartel agreements are economically unstable in that there is an incentive

for members to cheat by selling at below the cartel's agreed price or

selling more than the cartel's production quotas. Many cartels that

attempt to set product prices are unsuccessful in the long term.

Empirical studies of 20th-century cartels have determined that the mean

duration of discovered cartels is from 5 to 8 years.

Once a cartel is broken, the incentives to form a new cartel return,

and the cartel may be re-formed. Publicly known cartels that do not

follow this business cycle include, by some accounts, OPEC.

Cartels often practice price fixing internationally. When the

agreement to control prices is sanctioned by a multilateral treaty or

protected by national sovereignty, no antitrust actions may be

initiated. OPEC countries partially control the price of oil, and the International Air Transport Association (IATA) fixes prices for international airline tickets while the organization is excepted from antitrust law.

Organization

Drawing

upon research on organizational misconduct, scholars in economics,

sociology and management have studied the organization of cartels.

They have paid attention to the way cartel participants work together

to conceal their activities from antitrust authorities. Even more than

reaching efficiency, participating firms need to ensure that their

collective secret is maintained.

It has also been argued that the diversity of the participants (e.g.,

age and size of the firms) influences their ability to coordinate to

avoid being detected.

Cartel theory versus antitrust concept

The scientific analysis of cartels is based on cartel theory. It was pioneered in 1883 by the Austrian economist Friedrich Kleinwächter and in its early stages was developed mainly by German-speaking scholars.

These scholars tended to regard cartels as an acceptable part of the

economy. At the same time, American lawyers increasingly turned against trade restrictions, including all cartels. The Sherman act,

which impeded the formation and activities of cartels, was passed in

the United States in 1890. The American viewpoint, supported by

activists like Thurman Arnold and Harley M. Kilgore, eventually prevailed when governmental policy in Washington could have a larger impact in World War II.

Legislation

Because cartels are likely to have an impact on market positions, they are subjected to competition law, which is executed by governmental competition regulators. Very similar regulations apply to corporate mergers. A single entity that holds a monopoly is not considered a cartel but can be sanctioned through other abuses of its monopoly.

Prior to World War II, members of cartels could sign contracts that were

enforceable in courts of law except in the United States. Before 1945,

cartels were tolerated in Europe and specifically promoted as a business

practice in German-speaking countries. In U.S. v. National Lead Co. et al., the Supreme Court of the United States noted the testimony of individuals who cited that a cartel, in its versatile form, is

a combination of producers for the purpose of regulating production and, frequently, prices, and an association by agreement of companies or sections of companies having common interests so as to prevent extreme or unfair competition.

Today, price fixing by private entities is illegal under the

antitrust laws of more than 140 countries. The commodities of prosecuted

international cartels include lysine, citric acid, graphite electrodes, and bulk vitamins.

In many countries, the predominant belief is that cartels are contrary

to free and fair competition, considered the backbone of political

democracy.

Maintaining cartels continues to become harder for cartels. Even if

international cartels cannot be regulated as a whole by individual

nations, their individual activities in domestic markets are affected.

Unlike other cartels, export cartels are legal in virtually all

jurisdictions, despite their harmful effects on affected markets.

Examples

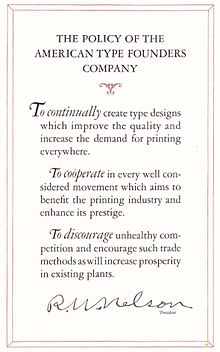

The printing equipment company American Type Founders (ATF) explicitly states in its 1923 manual that its goal is to "discourage unhealthy competition" in the printing industry.

- Asian Racing Federation: The Asian Racing Federation formed a cartel, documented in the Good Neighbour Policy signed on September 1, 2003.

- British Valve Association

- De Beers

- Federation of Quebec Maple Syrup Producers: Canada's maple syrup cartel, which controls the pricing of maple syrup worldwide. Formed in 1966. Called "the OPEC of the maple syrup world" by The Economist

- International Rail Makers Association

- OPEC: As its name suggests, OPEC is organised by sovereign states. Under traditional legal views, it cannot be held to antitrust enforcement in other jurisdictions under the doctrine of state immunity under public international law.

- Phoebus cartel (1925–1955) for light bulbs

- Rhenish-Westphalian Coal Syndicate: Worldwide, the most famous and renowned cartel of its life span (1893–1945)

- Seven Sisters (oil companies)

- Swiss Cheese Union: Many trade associations, especially in industries dominated by only a few major companies, have been accused of being fronts for cartels or facilitating secret meetings among cartel members. The now-defunct Swiss Cheese Union discouraged competition throughout the dairy industry in 20th century Switzerland.

- Standard Oil

- Trade unions: Although cartels are usually thought of as a group of corporations, the free-market economist Charles W. Baird considers trade unions to be cartels because they seek to raise the price of labor (wages) by preventing competition. Negotiated cartelism is a labor arrangement in which labor prices are held above the market-clearing level through union leverage over employers.