From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Svalbard (

SVAHL-bar,

prior to 1925 known as

Spitsbergen, or

Spitzbergen, is a

Norwegian archipelago in the

Arctic Ocean. Situated north of

mainland Europe, it is about midway between continental Norway and the

North Pole. The islands of the group range from

74° to

81° north latitude, and from

10° to

35° east longitude. The largest island is

Spitsbergen, followed by

Nordaustlandet and

Edgeøya. While part of the Kingdom of Norway since 1925, Svalbard is not part of geographical

Norway proper; administratively, the archipelago is not part of any

Norwegian county, but forms an

unincorporated area administered by a

governor appointed by the Norwegian government, and a special jurisdiction subject to the

Svalbard Treaty that is, unlike Norway proper, outside of the

Schengen Area, the

Nordic Passport Union and the

European Economic Area.

Since 2002, Svalbard's main settlement,

Longyearbyen, has had an

elected local government, somewhat similar to

mainland municipalities. Other settlements include the Russian mining community of

Barentsburg, the research station of

Ny-Ålesund, and the mining outpost of

Sveagruva. Other settlements are farther north, but are populated only by rotating groups of researchers.

The islands were first used as a

whaling base by whalers who sailed far north in pursuit of whales for

blubber in the 17th and 18th centuries, after which they were abandoned.

Coal mining started at the beginning of the 20th century, and several permanent communities were established. The

Svalbard Treaty of 1920 recognizes Norwegian

sovereignty, and the 1925

Svalbard Act made Svalbard a full part of the Kingdom of Norway. They also established Svalbard as a

free economic zone and a

demilitarized zone. The Norwegian

Store Norske and the Russian

Arktikugol remain the only mining companies in place. Research and tourism have become important supplementary industries, with the

University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) and the

Svalbard Global Seed Vault playing critical roles. No roads connect the settlements; instead

snowmobiles, aircraft and boats serve inter-community transport.

Svalbard Airport, Longyear serves as the main gateway.

The archipelago features an

Arctic climate, although with significantly higher temperatures than other areas at the same latitude. The

flora take advantage of the long period of

midnight sun to compensate for the

polar night. Svalbard is a breeding ground for many

seabirds, and also features

polar bears,

reindeer, the

Arctic fox, and certain

marine mammals.

Seven national parks

and twenty-three nature reserves cover two-thirds of the archipelago,

protecting the largely untouched, yet fragile, natural environment.

Approximately 60% of the archipelago is covered with

glaciers, and the islands feature many mountains and

fjords.

Svalbard and Jan Mayen are collectively assigned the

ISO 3166-1 alpha-2

country code "SJ". Both areas are administered by Norway, though they

are separated by a distance of over 950 kilometres (590 miles; 510

nautical miles) and have very different administrative structures.

Etymology

The name Svalbard comes from an older native name for the archipelago,

Svalbarð, composed of the well-attested Old Norse words

svalr ("cold") and

barð ("edge; ridge, turf, beard"). The name

Spitsbergen originated with Dutch navigator and explorer

Willem Barentsz, who described the "pointed mountains" or, in Dutch,

spitse bergen

that he saw on the west coast of the main island, Spitsbergen. Barentsz

did not recognize that he had discovered an archipelago, and

consequently the name

Spitsbergen long remained in use both for the main island and for the archipelago as a whole.

Geography

The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 defines Svalbard as all islands, islets and

skerries from 74° to 81° north latitude, and from 10° to 35° east longitude. The land area is 61,022 km

2

(23,561 sq mi), and dominated by the island of Spitsbergen, which

constitutes more than half the archipelago, followed by Nordaustlandet

and Edgeøya. All settlements are located on Spitsbergen, except the meteorological outposts on

Bjørnøya and

Hopen.

The Norwegian state took possession of all unclaimed land, or 95.2% of

the archipelago, at the time the Svalbard Treaty entered into force;

Store Norske, a Norwegian coal mining company, owns 4%,

Arktikugol, a Russian coal mining company, owns 0.4%, while other private owners hold 0.4%.

Since Svalbard is located north of the

Arctic Circle, it experiences

midnight sun in summer and

polar night

in winter. At 74° north, the midnight sun lasts 99 days and polar night

84 days, while the respective figures at 81° are 141 and 128 days. In

Longyearbyen, midnight sun lasts from 20 April until 23 August, and polar night lasts from 26 October to 15 February. In winter, the combination of

full moon and reflective snow can give additional light.

Due to the Earth's tilt and the high latitude, Svalbard has extensive

twilights. Longyearbyen sees the first and last day of polar night

having seven and a half hours of twilight, whereas the perpetual light

lasts for two weeks longer than the midnight sun.

On the summer solstice, the sun bottoms out at 12° sun angle in the

middle of the night, being much higher during night than in mainland

Norway's polar light areas. However, the daytime strength of the sun remains as low as 35°.

Glacial ice covers 36,502 km

2 (14,094 sq mi) or 60% of Svalbard; 30% is barren rock while 10% is vegetated. The largest glacier is

Austfonna (8,412 km

2 or 3,248 sq mi) on Nordaustlandet, followed by

Olav V Land and

Vestfonna. During summer, it is possible to ski from

Sørkapp in the south to the north of Spitsbergen, with only a short distance not being covered by snow or glacier.

Kvitøya is 99.3% covered by glacier.

The landforms of Svalbard were created through

repeated ice ages, when glaciers cut the former plateau into fjords, valleys, and mountains. The tallest peak is

Newtontoppen (1,717 m or 5,633 ft), followed by

Perriertoppen (1,712 m or 5,617 ft),

Ceresfjellet (1,675 m or 5,495 ft),

Chadwickryggen (1,640 m or 5,380 ft), and

Galileotoppen (1,637 m or 5,371 ft). The longest fjord is

Wijdefjorden (108 km or 67 mi), followed by

Isfjorden (107 km or 66 mi),

Van Mijenfjorden (83 km or 52 mi),

Woodfjorden (64 km or 40 mi), and

Wahlenbergfjorden (46 km or 29 mi). Svalbard is part of the

High Arctic Large Igneous Province, and experienced Norway's strongest earthquake on 6 March 2009, which hit a magnitude of 6.5.

History

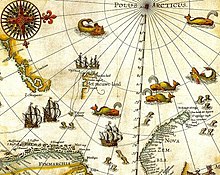

Svalbard,

here mapped for the first time, is indicated as "Het Nieuwe Land"

(Dutch for "the New Land"), center-left. Portion of 1599 map of Arctic

exploration by

Willem Barentsz.

Dutch discovery, exploration, and mapping of a terra nullius

The Dutchman

Willem Barentsz

made the first discovery of the archipelago in 1596, when he sighted

the coast of the island of Spitsbergen while searching for the

Northern Sea Route.

The first recorded landing on the islands of Svalbard dates to 1604, when an English ship landed at

Bjørnøya, or Bear Island, and started hunting

walrus. Annual expeditions soon followed, and Spitsbergen became a base for hunting the

bowhead whale from 1611.

Because of the lawless nature of the area, English, Danish, Dutch, and

French companies and authorities tried to use force to keep out other

countries' fleets.

17th–18th centuries

The whaling station of the Amsterdam chamber of the Northern Company in

Smeerenburg, by

Cornelis de Man (1639), but based on a painting of a

Dansk hvalfangststation (Danish whaling station) by A.B.R. Speeck (1634), which represented the Danish station in Copenhagen Bay (Kobbefjorden)

Smeerenburg was one of the first settlements, established by the Dutch in 1619.

Smaller bases were also built by the English, Danish, and French. At

first the outposts were merely summer camps, but from the early 1630s, a

few individuals started to

overwinter. Whaling at Spitsbergen lasted until the 1820s, when the Dutch, British, and Danish whalers moved elsewhere in the Arctic. By the late 17th century,

Russian hunters arrived; they overwintered to a greater extent and hunted land mammals such as the polar bear and fox.

19th century

After the

Anglo-Russian War in 1809, Russian activity on Svalbard diminished, and ceased by the 1820s.

Norwegian hunting—mostly for walrus—started in the 1790s. The first

Norwegian citizens to reach Spitsbergen proper were a number of Coast

Sámi people from the

Hammerfest region, who were hired as part of a Russian crew for an expedition in 1795. Norwegian whaling was abandoned about the same time as the Russians left, but whaling continued around Spitsbergen until the 1830s, and around Bjørnøya until the 1860s.

20th century

Svalbard Treaty and Norwegian sovereignty

By the 1890s, Svalbard had become a destination for Arctic tourism,

coal deposits had been found and the islands were being used as a base

for

Arctic exploration. The first mining was along Isfjorden by Norwegians in 1899; by 1904, British interests had established themselves in

Adventfjorden and started the first all-year operations. Production in Longyearbyen, by American interests, started in 1908;

and Store Norske established itself in 1916, as did other Norwegian

interests during the war, in part by buying American interests.

Discussions to establish the sovereignty of the archipelago commenced in the 1910s, but were interrupted by

World War I. On 9 February 1920, following the

Paris Peace Conference, the

Svalbard Treaty

was signed, granting full sovereignty to Norway. However, all signatory

countries were granted non-discriminatory rights to fishing, hunting,

and mineral resources. The treaty took effect on 14 August 1925, at the same time as the

Svalbard Act regulated the archipelago and the first

governor,

Johannes Gerckens Bassøe, took office.

The archipelago has traditionally been known as Spitsbergen, and the

main island as West Spitsbergen. From the 1920s, Norway renamed the

archipelago Svalbard, and the main island became Spitsbergen. Kvitøya, Kong Karls Land, Hopen, and Bjørnøya were not regarded as part of the Spitsbergen archipelago. Russians have traditionally called the archipelago Grumant (

Грумант). The

Soviet Union retained the name Spitsbergen (

Шпицберген) to support undocumented claims that Russians were the first to discover the island. In 1928, Italian explorer

Umberto Nobile and the crew of the airship

Italia crashed on the icepack off the coast of

Foyn Island. The subsequent rescue attempts were covered extensively in the press and Svalbard received short-lived fame as a result.

Second World War

Demolition of the wireless station during Operation Gauntlet in 1941

Svalbard, known to both British and Germans as Spitsbergen, was little affected by the

German invasion of Norway in April 1940. The settlements continued to operate as before, mining coal and monitoring the weather.

In July 1941, following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the

Royal Navy

reconnoitred the islands with a view to using them as a base of

operations to facilitate sending supplies to north Russia, but the idea

was rejected as too impractical.

Instead, with the agreement of the Soviets and the Norwegian government

in exile, in August 1941 the Norwegian and Soviet settlements on

Svalbard were evacuated, and facilities there destroyed, in

Operation Gauntlet.

However the Norwegian government in exile decided it would be important

politically to establish a garrison in the islands, which was done in

May 1942 during

Operation Fritham.

Meanwhile, the Germans had responded to the destruction of

weather station by establishing a reporting station of their own,

codenamed

"Banso", in October 1941.

This was chased away in November by a visit from four British warships,

but later returned. A second station, "Knospel", was established at

Ny Alesund in 1941, remaining until 1942. In May 1942, after the arrival of the Fritham force, the German unit at Banso was evacuated.

In September 1943 in

Operation Zitronella a German task force, which included the battleship

Tirpitz, was sent to attack the garrison and destroy the settlements at Longyearbyen and Barentsburg.

This was achieved, but had little long-term effect: after their

departure the Norwegians returned and re-established their presence.

In September 1944, the Germans set up their last weather station,

Operation Haudegen

in NordOstLand; this remained functioning until after the German

surrender. On 4 September 1945, the soldiers were picked up by a

Norwegian seal hunting vessel and surrendered to its captain. This group

of men were the last German troops to surrender after the Second World

War.

After the war, the Soviet Union proposed common Norwegian and

Soviet administration and military defence of Svalbard. This was

rejected in 1947 by Norway, which two years later joined

NATO. The Soviet Union retained high civilian activity on Svalbard, in part to ensure that the archipelago was not used by NATO.

Post-war

After the war, Norway re-established operations at Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund, while the Soviet Union established mining in Barentsburg,

Pyramiden and

Grumant.

The mine at Ny-Ålesund had several fatal accidents, killing 71 people

while it was in operation from 1945 to 1954 and from 1960 to 1963. The

Kings Bay Affair, caused by the 1962 accident killing 21 workers, forced

Gerhardsen's Third Cabinet to resign. From 1964, Ny-Ålesund became a research outpost, and a facility for the

European Space Research Organisation. Petroleum test drilling was started in 1963 and continued until 1984, but no commercially viable fields were found. From 1960, regular charter flights were made from the mainland to a field at

Hotellneset; in 1975, Svalbard Airport, Longyear opened, allowing year-round services.

During the

Cold War,

the Soviet Union comprised about two-thirds of the population on the

islands (Norwegians making up the remaining third) with the population

of the archipelago slightly under 4,000. Russian activity has diminished considerably since then, falling from 2,500 to 450 people from 1990 to 2010. Grumant was closed after it was depleted in 1962.

Pyramiden was closed in 1998. Coal exports from Barentsburg ceased in 2006 because of a fire, but resumed in 2010. The Russian community has also experienced two air accidents,

Vnukovo Airlines Flight 2801, which killed 141 people, and the

Heerodden helicopter accident, which killed three people.

Longyearbyen remained purely a company town until 1989 when

utilities, culture, and education was separated into Svalbard

Samfunnsdrift. In 1993, it was sold to the national government and the University Centre was established. Through the 1990s, tourism increased and the town developed an economy independent of Store Norske and the mining. Longyearbyen was incorporated on 1 January 2002, receiving a community council.

Population

Demographics

In 2016, Svalbard had a population of 2,667, of which 423 were

Russian and Ukrainian, 10 Polish, and 322 non-Norwegians living in

Norwegian settlements.

The largest non-Norwegian groups in Longyearbyen in 2005 were from

Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and Thailand.

Settlements

Longyearbyen

is the largest settlement on the archipelago, the seat of the governor

and the only town to be incorporated. The town features a hospital,

primary and secondary school,

university, sports center with a swimming pool, library, culture center, cinema, bus transport, hotels, a bank, and several museums. The newspaper

Svalbardposten is published weekly. Only a small fraction of the mining activity remains at Longyearbyen; instead, workers commute to

Sveagruva (or Svea) where Store Norske operates a mine. Sveagruva is a

dormitory town, with workers commuting from Longyearbyen weekly.

Ny-Ålesund is a permanent settlement based entirely around research. Formerly a mining town, it is still a

company town operated by the Norwegian state-owned

Kings Bay.

While there is some tourism there, Norwegian authorities limit access

to the outpost to minimize impact on the scientific work. Ny-Ålesund has a winter population of 35 and a summer population of 180.

The

Norwegian Meteorological Institute

has outposts at Bjørnøya and Hopen, with respectively ten and four

people stationed. Both outposts can also house temporary research staff. Poland operates the

Polish Polar Station at

Hornsund, with ten permanent residents.

The abandoned Soviet mining town of

Pyramiden

Barentsburg is the only permanently inhabited Russian settlement after

Pyramiden

was abandoned in 1998. It is a company town: all facilities are owned

by Arktikugol, which operates a coal mine. In addition to the mining

facilities, Arktikugol has opened a hotel and souvenir shop, catering

for tourists taking day trips or hikes from Longyearbyen.

The village features facilities such as a school, library, sports

center, community center, swimming pool, farm, and greenhouse. Pyramiden

features similar facilities; both are built in typical post-World War

II Soviet architectural and planning style and contain the world's two

most northerly

Lenin statues and other

socialist realism artwork. As of 2013,

a handful of workers are stationed in the largely abandoned Pyramiden

to maintain the infrastructure and run the hotel, which has been

re-opened for tourists.

Religion

Politics

The

Svalbard Treaty of 1920 established full Norwegian sovereignty over the archipelago. The islands are, unlike the

Norwegian Antarctic Territory, a part of the Kingdom of Norway and not a

dependency.

The treaty came into effect in 1925, following the Svalbard Act. All

forty signatory countries of the treaty have the right to conduct

commercial activities on the archipelago without discrimination,

although all activity is subject to Norwegian legislation. The treaty

limits Norway's right to collect taxes to that of financing services on

Svalbard. Therefore, Svalbard has a lower

income tax than mainland Norway, and there is no

value added tax. There is a separate budget for Svalbard to ensure compliance. Svalbard is a

demilitarized zone,

as the treaty prohibits the establishment of military installations.

Norwegian military activity is limited to fishery surveillance by the

Norwegian Coast Guard as the treaty requires Norway to protect the natural environment.

There are no restrictions on foreigners migrating in, and hence no

visa requirement.

The Svalbard Act established the institution of the Governor of Svalbard (

Norwegian:

Sysselmannen), who holds the responsibility as both

county governor and

chief of police, as well as holding other authority granted from the executive branch. Duties include

environmental policy,

family law,

law enforcement,

search and rescue,

tourism management, information services, contact with foreign

settlements, and judge in some areas of maritime inquiries and judicial

examinations—albeit never in the same cases as acting as police. Since 2015,

Kjerstin Askholt has been governor; she is assisted by a staff of 26 professionals. The institution is subordinate to the

Ministry of Justice and the Police, but reports to other ministries in matters within their portfolio.

Since 2002,

Longyearbyen Community Council has had many of the same responsibilities of a

municipality, including utilities, education, cultural facilities, fire department, roads, and ports.

No care or nursing services are available, nor is welfare payment

available. Norwegian residents retain pension and medical rights through

their mainland municipalities. The hospital is part of

University Hospital of North Norway, while the airport is operated by state-owned

Avinor. Ny-Ålesund and Barentsburg remain

company towns with all infrastructure owned by Kings Bay and Arktikugol, respectively. Other public offices with presence on Svalbard are the

Norwegian Directorate of Mining, the

Norwegian Polar Institute, the

Norwegian Tax Administration, and the

Church of Norway. Svalbard is subordinate to

Nord-Troms District Court and

Hålogaland Court of Appeal, both located in

Tromsø.

In September 2010, a treaty was made between Russia and Norway fixing the boundary between the Svalbard archipelago and the

Novaya Zemlya archipelago.

Increased interest in petroleum exploration in the Arctic raised

interest in a resolution of the dispute. The agreement takes into

account the relative positions of the archipelagos, rather than being

based simply on northward extension of the continental border of Norway

and Russia.

Economy

The three main industries on Svalbard are

coal mining,

tourism, and

research.

In 2007, there were 484 people working in the mining sector, 211 people

working in the tourism sector, and 111 people working in the education

sector. The same year, the mining gave a revenue of 2.008 billion

Norwegian kroner (US$227,791,078), tourism 317 million kroner ($35,967,202), and research 142 million kroner ($16,098,404). In 2006, the average income for economically active people was 494,700 kroner; 23% higher than on the mainland.

Almost all housing is owned by the various employers and institutions

and rented to their employees; there are only a few privately owned

houses, most of which are recreational cabins. Because of this, it is

nearly impossible to live on Svalbard without working for an established

institution.

Since the resettlement of Svalbard in the early 20th century, coal mining has been the dominant commercial activity.

Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, a subsidiary of the

Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry,

operates Svea Nord in Sveagruva and Mine 7 in Longyearbyen. The former

produced 3.4 million tonnes in 2008, while the latter uses 35% of its

output to fuel the Longyearbyen Power Station. Since 2007, there has not

been any significant mining by the Russian state-owned Arktikugol in

Barentsburg. There have previously been performed test drilling for

petroleum on land, but these did not give satisfactory results for

permanent operation. The Norwegian authorities do not allow offshore

petroleum activities for environmental reasons, and the land formerly

test-drilled on have been protected as natural reserves or national

parks. In 2011, a 20-year plan to develop offshore oil and gas resources around Svalbard was announced.

Svalbard has historically been a base for both

whaling and

fishing. Norway claimed a 200-nautical-mile (370 km; 230 mi)

exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around Svalbard in 1977, with 31,688 square kilometres (12,235 sq mi) of

internal waters and 770,565 square kilometres (297,517 sq mi) of EEZ. Norway retains a restrictive fisheries policy in the zone, and the claims are disputed by Russia.

Tourism is focused on the environment and is centered on Longyearbyen.

Activities include hiking, kayaking, walks through glacier caves, and

snowmobile

and dog-sled safari. Cruise ships generate a significant portion of the

traffic, including both stops by offshore vessels and expeditionary

cruises starting and ending in Svalbard. Traffic is strongly

concentrated between March and August; overnights have quintupled from

1991 to 2008, when there were 93,000 guest-nights.

Research on Svalbard centers on Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund, the

most accessible areas in the high Arctic. The treaty grants permission

for any nation to conduct research on Svalbard, resulting in the

Polish Polar Station and the Chinese

Arctic Yellow River Station, plus Russian facilities in Barentsburg. The

University Centre in Svalbard

in Longyearbyen offers undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate

courses to 350 students in various arctic sciences, particularly

biology,

geology, and

geophysics.

Courses are provided to supplement studies at the mainland

universities; there are no tuition fees and courses are held in English,

with Norwegian and international students equally represented.

The

Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a

seedbank

to store seeds from as many of the world's crop varieties and their

botanical wild relatives as possible. A cooperation between the

government of Norway and the

Global Crop Diversity Trust,

the vault is cut into rock near Longyearbyen, keeping it at a natural

−6 °C (21 °F) and refrigerating the seeds to −18 °C (0 °F).

One source of income for the area was, until 2015, visiting

cruise ships. The Norwegian government became concerned about large

numbers of cruise ship passengers suddenly landing at small settlements

such as Ny-Ålesund, which is conveniently close to the

barren-yet-picturesque

Magdalena Fjord.

With the increasing size of the larger ships, up to 2,000 people can

potentially appear in a community that normally numbers less than 40. As

a result, the government severely restricted the size of cruise ships

that may visit.

Transport

Snowmobiles are an important mode of transport in Svalbard, such as here at Longyearbyen.

Within Longyearbyen, Barentsburg, and Ny-Ålesund, there are road systems, but they do not connect with each other.

Off-road

motorized transport is prohibited on bare ground, but snowmobiles are

used extensively during winter—both for commercial and recreational

activities. Transport from Longyearbyen to Barentsburg (45 km or 28 mi)

and Pyramiden (100 km or 62 mi) is possible by snowmobile in winter, or

by ship all year round. All settlements have ports and Longyearbyen has a

bus system.

Svalbard Airport, Longyear, located 3 kilometres (2 mi) from Longyearbyen, is the only airport offering air transport off the archipelago.

Scandinavian Airlines has daily scheduled services to

Tromsø and

Oslo. Low-cost carrier

Norwegian Air Shuttle

also has a service between Oslo and Svalbard, operating three or four

times a week; there are also irregular charter services to Russia.

Finnair operated service from

Helsinki,

operating three times per week between June and August 2016, but

Norwegian authorities did not allow this route, citing the 1978

bilateral agreement on air traffic between Finland and Norway.

Lufttransport provides regular corporate charter services from Longyearbyen to

Ny-Ålesund Airport and

Svea Airport for Kings Bay and Store Norske; these flights are generally not available to the public. There are

heliports

in Barentsburg and Pyramiden, and helicopters are frequently used by

the governor and to a lesser extent the mining company Arktikugol.

Climate

The climate of Svalbard is dominated by its high latitude, with the

average summer temperature at 4 to 6 °C (39 to 43 °F) and January

averages at −16 to −12 °C (3 to 10 °F).

The

West Spitsbergen Current, the northernmost branch of the

North Atlantic Current

system, moderates Svalbard's temperatures, particularly during winter.

Winter temperatures in Svalbard are up to 2 °C (4 °F) higher than those

at similar latitudes in Russia and Canada. The warm Atlantic water keeps

the surrounding waters open and navigable most of the year. The

interior fjord areas and valleys, sheltered by the mountains, have

larger temperature differences than the coast, giving about 20 °C

(36 °F) warmer summer temperatures and 3 °C (5 °F) colder winter

temperatures. On the south of Spitsbergen, the temperature is slightly

higher than further north and west. During winter, the temperature

difference between south and north is typically 5 °C (9 °F), and about

3 °C (5 °F) in summer.

Bear Island has average temperatures even higher than the rest of the archipelago.

Svalbard is where cold

polar air

from the north and mild, wet sea air from the south meet, creating low

pressure, changeable weather and strong winds, particularly in winter;

in January, a strong breeze is registered 17% of the time at

Isfjord Radio, but only 1% of the time in July. In summer, particularly away from land,

fog is common, with visibility under 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) registered

20% of the time in July and 1% of the time in January, at Hopen and

Bjørnøya.

Precipitation is frequent, but falls in small quantities, typically

less than 400 millimetres (16 in) per year in western Spitsbergen. More

rain falls on the uninhabited east side, where there can be more than

1,000 millimetres (39 in).

2016 was the warmest year on record at Svalbard Airport, with a

remarkable mean temperature of 0.0 °C (32.0 °F), 7.5 °C (13.5 °F) above

the 1961–90 average, and more comparable to a location at the

arctic circle.

The coldest temperature of the year was as high as −18 °C (0 °F),

warmer than the mean minimum in a normal January, February or March. In

the same year, the number of days when there was rainfall equalled the

number of days when there was snowfall, a significant deviation from the

usual pattern whereby there would be at least twice as many snow days.

Global warming

has resulted in noticeable climatic changes on Svalbard. Between 1970

and 2020, the average temperature on Svalbard rose by 4 degrees Celsius,

and in the winter months by 7 degrees.

On July 25, 2020, a new record temperature of 21.7 degrees Celsius was

measured for the Svalbard archipelago, which is also the highest

temperature ever recorded in the European part of the Arctic; In

addition, temperatures of over 20 degrees were measured four days in a

row in July 2020. As in large parts of the Arctic, the

ice–albedo feedback

effects can also be noticed on Svalbard: Due to the substantial ice

melt, ice surfaces are transformed into open water, the darker surface

of which absorbs more solar energy instead of reflecting it back; as a

result, these waters heat up and further ice in the area melts faster

and faster, creating more open waters, etc. A temperature increase of

between 7 and 10 degrees is expected on Svalbard by the end of the

century.

Nature

Polar bears are the iconic symbol of Svalbard, and one of the main tourist attractions.

The animals are protected and people moving outside the settlements are

required to have appropriate scare devices to ward off attacks. They

are also advised to carry a firearm for use as a last resort. A British schoolboy was killed by a polar bear in 2011. In July 2018, a polar bear was shot dead after it attacked and injured a polar bear guard leading tourists off a cruise ship. Svalbard and

Franz Joseph Land share a common population of 3,000 polar bears, with

Kong Karls Land being the most important breeding ground.

The

Svalbard reindeer (

R. tarandus platyrhynchus) is a distinct subspecies; although it was previously almost extinct, it can be legally hunted (as can Arctic fox). There are limited numbers of domesticated animals in the Russian settlements.

Svalbard has

permafrost and

tundra, with both low, middle, and high

Arctic vegetation. 165 species of plants have been found on the archipelago. Only those areas which defrost in the summer have vegetations, which accounts for about 10% of the archipelago. Vegetation is most abundant in Nordenskiöld Land, around Isfjorden and where affected by

guano. While there is little precipitation, giving the archipelago a

steppe climate, plants still have good access to water because the cold climate reduces evaporation. The growing season is very short, and may last only a few weeks.

Education

Longyearbyen School serves ages 6–18. It is the primary/secondary school in the

northernmost location on Earth. Once pupils reach ages 16 or 17, most families move to mainland Norway.

Barentsburg has its own school serving the Russian community; by 2014 it had three teachers, and its welfare funds had declined. A primary school served the community of

Pyramiden in the pre-1998 period.

Sports

Association football

is the most popular sport in Svalbard. There are three football pitches

(one at Barentsburg), but no stadiums because of the small population.

There is also an indoor hall adopted for multiple sports including

indoor football.