From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not due to any immediate external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that are associated with specific signs and symptoms. A disease may be caused by external factors such as pathogens or by internal dysfunctions. For example, internal dysfunctions of the immune system can produce a variety of different diseases, including various forms of immunodeficiency, hypersensitivity, allergies and autoimmune disorders.

In humans, disease is often used more broadly to refer to any condition that causes pain, dysfunction, distress, social problems, or death

to the person afflicted, or similar problems for those in contact with

the person. In this broader sense, it sometimes includes injuries, disabilities, disorders, syndromes, infections, isolated symptoms, deviant behaviors, and atypical variations

of structure and function, while in other contexts and for other

purposes these may be considered distinguishable categories. Diseases

can affect people not only physically, but also mentally, as contracting

and living with a disease can alter the affected person's perspective

on life.

Death due to disease is called death by natural causes. There are four main types of disease: infectious diseases, deficiency diseases, hereditary diseases (including both genetic diseases and non-genetic hereditary diseases), and physiological diseases. Diseases can also be classified in other ways, such as communicable versus non-communicable diseases. The deadliest diseases in humans are coronary artery disease (blood flow obstruction), followed by cerebrovascular disease and lower respiratory infections. In developed countries, the diseases that cause the most sickness overall are neuropsychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety.

The study of disease is called pathology, which includes the study of etiology, or cause.

Terminology

Concepts

In many cases, terms such as disease, disorder, morbidity, sickness and illness are used interchangeably; however, there are situations when specific terms are considered preferable.

- Disease

- The term disease broadly refers to any condition that impairs

the normal functioning of the body. For this reason, diseases are

associated with the dysfunction of the body's normal homeostatic processes. Commonly, the term is used to refer specifically to infectious diseases, which are clinically evident diseases that result from the presence of pathogenic microbial agents, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, multicellular organisms, and aberrant proteins known as prions. An infection or colonization that does not and will not produce clinically evident impairment of normal functioning, such as the presence of the normal bacteria and yeasts in the gut, or of a passenger virus, is not considered a disease. By contrast, an infection that is asymptomatic during its incubation period, but expected to produce symptoms later, is usually considered a disease. Non-infectious diseases are all other diseases, including most forms of cancer, heart disease, and genetic disease.

- Acquired disease

- An acquired disease is one that began at some point during one's

lifetime, as opposed to disease that was already present at birth, which

is congenital disease. Acquired

sounds like it could mean "caught via contagion", but it simply means

acquired sometime after birth. It also sounds like it could imply

secondary disease, but acquired disease can be primary disease.

- Acute disease

- An acute disease is one of a short-term nature (acute); the term sometimes also connotes a fulminant nature

- Chronic condition or chronic disease

- A chronic disease

is one that persists over time, often characterized as at least six

months but may also include illnesses that are expected to last for the

entirety of one's natural life.

- Congenital disorder or congenital disease

- A congenital disorder is one that is present at birth. It is often a genetic disease or disorder and can be inherited. It can also be the result of a vertically transmitted infection from the mother, such as HIV/AIDS.

- Genetic disease

- A genetic disorder or disease is caused by one or more genetic mutations. It is often inherited, but some mutations are random and de novo.

- Hereditary or inherited disease

- A hereditary disease is a type of genetic disease caused by genetic mutations that are hereditary (and can run in families)

- Iatrogenic disease

- An iatrogenic disease

or condition is one that is caused by medical intervention, whether as a

side effect of a treatment or as an inadvertent outcome.

- Idiopathic disease

- An idiopathic disease

has an unknown cause or source. As medical science has advanced, many

diseases with entirely unknown causes have had some aspects of their

sources explained and therefore shed their idiopathic status. For

example, when germs were discovered, it became known that they were a

cause of infection, but particular germs and diseases had not been

linked. In another example, it is known that autoimmunity is the cause of some forms of diabetes mellitus type 1,

even though the particular molecular pathways by which it works are not

yet understood. It is also common to know certain factors are associated

with certain diseases; however, association and causality are two very

different phenomena, as a third cause might be producing the disease, as

well as an associated phenomenon.

- Incurable disease

- A disease that cannot be cured. Incurable diseases are not necessarily terminal diseases, and sometimes a disease's symptoms can be treated sufficiently for the disease to have little or no impact on quality of life.

- Primary disease

- A primary disease is a disease that is due to a root cause of illness, as opposed to secondary disease, which is a sequela, or complication that is caused by the primary disease. For example, a common cold is a primary disease, where rhinitis is a possible secondary disease, or sequela. A doctor must determine what primary disease, a cold or bacterial infection, is causing a patient's secondary rhinitis when deciding whether or not to prescribe antibiotics.

- Secondary disease

- A secondary disease is a disease that is a sequela or complication of a prior, causal disease, which is referred to as the primary disease or simply the underlying cause (root cause).

For example, a bacterial infection can be primary, wherein a healthy

person is exposed to a bacteria and becomes infected, or it can be

secondary to a primary cause, that predisposes the body to infection.

For example, a primary viral infection that weakens the immune system could lead to a secondary bacterial infection. Similarly, a primary burn that creates an open wound could provide an entry point for bacteria, and lead to a secondary bacterial infection.

- Terminal disease

- A terminal disease is one that is expected to have the inevitable

result of death. Previously, AIDS was a terminal disease; it is now

incurable, but can be managed indefinitely using medications.

- Illness

- The terms illness and sickness are both generally used as synonyms for disease; however, the term illness is occasionally used to refer specifically to the patient's personal experience of his or her disease. In this model, it is possible for a person to have a disease without being ill (to have an objectively definable, but asymptomatic, medical condition, such as a subclinical infection, or to have a clinically apparent physical impairment but not feel sick or distressed by it), and to be ill without being diseased (such as when a person perceives a normal experience as a medical condition, or medicalizes

a non-disease situation in his or her life – for example, a person who

feels unwell as a result of embarrassment, and who interprets those

feelings as sickness rather than normal emotions). Symptoms of illness

are often not directly the result of infection, but a collection of evolved responses – sickness behavior by the body – that helps clear infection and promote recovery. Such aspects of illness can include lethargy, depression, loss of appetite, sleepiness, hyperalgesia, and inability to concentrate.

- Disorder

- A disorder is a functional abnormality or disturbance. Medical disorders can be categorized into mental disorders, physical disorders, genetic disorders, emotional and behavioral disorders, and functional disorders. The term disorder is often considered more value-neutral and less stigmatizing than the terms disease or illness, and therefore is preferred terminology in some circumstances. In mental health, the term mental disorder is used as a way of acknowledging the complex interaction of biological, social, and psychological factors in psychiatric conditions; however, the term disorder

is also used in many other areas of medicine, primarily to identify

physical disorders that are not caused by infectious organisms, such as metabolic disorders.

- Medical condition

- A medical condition is a broad term that includes all diseases, lesions, disorders, or nonpathologic condition that normally receives medical treatment, such as pregnancy or childbirth. While the term medical condition

generally includes mental illnesses, in some contexts the term is used

specifically to denote any illness, injury, or disease except for mental

illnesses. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the widely used psychiatric manual that defines all mental disorders, uses the term general medical condition to refer to all diseases, illnesses, and injuries except for mental disorders. This usage is also commonly seen in the psychiatric literature. Some health insurance policies also define a medical condition as any illness, injury, or disease except for psychiatric illnesses.

- As it is more value-neutral than terms like disease, the term medical condition

is sometimes preferred by people with health issues that they do not

consider deleterious. On the other hand, by emphasizing the medical

nature of the condition, this term is sometimes rejected, such as by

proponents of the autism rights movement.

- The term medical condition is also a synonym for medical state,

in which case it describes an individual patient's current state from a

medical standpoint. This usage appears in statements that describe a

patient as being in critical condition, for example.

- Morbidity

- Morbidity (from Latin morbidus 'sick, unhealthy') is a diseased state, disability, or poor health due to any cause.

The term may refer to the existence of any form of disease, or to the

degree that the health condition affects the patient. Among severely

ill patients, the level of morbidity is often measured by ICU scoring systems. Comorbidity is the simultaneous presence of two or more medical conditions, such as schizophrenia and substance abuse.

- In epidemiology and actuarial science, the term "morbidity rate" can refer to either the incidence rate, or the prevalence of a disease or medical condition. This measure of sickness is contrasted with the mortality rate

of a condition, which is the proportion of people dying during a given

time interval. Morbidity rates are used in actuarial professions, such

as health insurance, life insurance, and long-term care insurance, to

determine the correct premiums to charge to customers. Morbidity rates

help insurers predict the likelihood that an insured will contract or

develop any number of specified diseases.

- Pathosis or pathology

- Pathosis (plural pathoses) is synonymous with disease. The word pathology also has this sense, in which it is commonly used by physicians in the medical literature, although some editors prefer to reserve pathology to its other senses. Sometimes a slight connotative shade causes preference for pathology or pathosis implying "some [as yet poorly analyzed] pathophysiologic process" rather than disease implying "a specific disease entity as defined by diagnostic criteria being already met". This is hard to quantify denotatively, but it explains why cognitive synonymy is not invariable.

- Syndrome

- A syndrome is the association of several signs and symptoms, or other characteristics that often occur together, regardless of whether the cause is known. Some syndromes such as Down syndrome are known to have only one cause (an extra chromosome at birth). Others such as Parkinsonian syndrome are known to have multiple possible causes. Acute coronary syndrome, for example, is not a single disease itself but is rather the manifestation of any of several diseases including myocardial infarction secondary to coronary artery disease. In yet other syndromes, however, the cause is unknown.

A familiar syndrome name often remains in use even after an underlying

cause has been found or when there are a number of different possible

primary causes. Examples of the first-mentioned type are that Turner syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome

are still often called by the "syndrome" name despite that they can

also be viewed as disease entities and not solely as sets of signs and

symptoms.

- Predisease

- Predisease is a subclinical or prodromal vanguard of a disease. Prediabetes and prehypertension are common examples. The nosology or epistemology of predisease is contentious, though, because there is seldom a bright line differentiating a legitimate concern for subclinical/prodromal/premonitory status (on one hand) and conflict of interest–driven disease mongering or medicalization

(on the other hand). Identifying legitimate predisease can result in

useful preventive measures, such as motivating the person to get a

healthy amount of physical exercise, but labeling a healthy person with an unfounded notion of predisease can result in overtreatment, such as taking drugs that only help people with severe disease or paying for drug prescription instances whose benefit–cost ratio is minuscule (placing it in the waste category of CMS' "waste, fraud, and abuse" classification). Three requirements for the legitimacy of calling a condition a predisease are:

- a truly high risk for progression to disease – for example, a pre-cancer will almost certainly turn into cancer over time

- actionability for risk reduction – for example, removal of the

precancerous tissue prevents it from turning into a potentially deadly

cancer

- benefit that outweighs the harm of any interventions taken –

removing the precancerous tissue prevents cancer, and thus prevents a

potential death from cancer.

Types by body system

- Mental

- Mental illness is a broad, generic label for a category of illnesses that may include affective or emotional

instability, behavioral dysregulation, cognitive dysfunction or

impairment. Specific illnesses known as mental illnesses include major depression, generalized anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,

to name a few. Mental illness can be of biological (e.g., anatomical,

chemical, or genetic) or psychological (e.g., trauma or conflict)

origin. It can impair the affected person's ability to work or study and

can harm interpersonal relationships. The term insanity is used technically as a legal term.

- Organic

- An organic disease is one caused by a physical or physiological

change to some tissue or organ of the body. The term sometimes excludes

infections. It is commonly used in contrast with mental disorders. It

includes emotional and behavioral disorders if they are due to changes

to the physical structures or functioning of the body, such as after a

stroke or a traumatic brain injury, but not if they are due to psychosocial issues.

Stages

In an infectious disease, the incubation period is the time between infection and the appearance of symptoms. The latency period

is the time between infection and the ability of the disease to spread

to another person, which may precede, follow, or be simultaneous with

the appearance of symptoms. Some viruses also exhibit a dormant phase,

called viral latency, in which the virus hides in the body in an inactive state. For example, varicella zoster virus causes chickenpox in the acute phase; after recovery from chickenpox, the virus may remain dormant in nerve cells for many years, and later cause herpes zoster (shingles).

- Acute disease

- An acute disease is a short-lived disease, like the common cold.

- Chronic disease

- A chronic disease

is one that lasts for a long time, usually at least six months. During

that time, it may be constantly present, or it may go into remission and periodically relapse.

A chronic disease may be stable (does not get any worse) or it may be

progressive (gets worse over time). Some chronic diseases can be

permanently cured. Most chronic diseases can be beneficially treated,

even if they cannot be permanently cured.

- Clinical disease

- One that has clinical consequences; in other words, the stage of the

disease that produces the characteristic signs and symptoms of that

disease. AIDS is the clinical disease stage of HIV infection.

- Cure

- A cure is the end of a medical condition or a treatment that is very likely to end it, while remission

refers to the disappearance, possibly temporarily, of symptoms.

Complete remission is the best possible outcome for incurable diseases.

- Flare-up

- A flare-up can refer to either the recurrence of symptoms or an onset of more severe symptoms.

- Progressive disease

- Progressive disease

is a disease whose typical natural course is the worsening of the

disease until death, serious debility, or organ failure occurs. Slowly

progressive diseases are also chronic diseases; many are also degenerative diseases. The opposite of progressive disease is stable disease or static disease: a medical condition that exists, but does not get better or worse.

- Refractory disease

- A refractory disease is a disease that resists treatment, especially

an individual case that resists treatment more than is normal for the

specific disease in question.

- Subclinical disease

- Also called silent disease, silent stage, or asymptomatic disease. This is a stage in some diseases before the symptoms are first noted.

- Terminal phase

- If a person will die soon from a disease, regardless of whether that

disease typically causes death, then the stage between the earlier

disease process and active dying is the terminal phase.

Extent

- Localized disease

- A localized disease is one that affects only one part of the body, such as athlete's foot or an eye infection.

- Disseminated disease

- A disseminated disease has spread to other parts; with cancer, this is usually called metastatic disease.

- Systemic disease

- A systemic disease is a disease that affects the entire body, such as influenza or high blood pressure.

Classification

Diseases may be classified by cause, pathogenesis (mechanism by which the disease is caused), or by symptom(s). Alternatively, diseases may be classified according to the organ system involved, though this is often complicated since many diseases affect more than one organ.

A chief difficulty in nosology is that diseases often cannot be

defined and classified clearly, especially when cause or pathogenesis

are unknown. Thus diagnostic terms often only reflect a symptom or set

of symptoms (syndrome).

Classical classification of human disease derives from the

observational correlation between pathological analysis and clinical

syndromes. Today it is preferred to classify them by their cause if it

is known.

The most known and used classification of diseases is the World Health Organization's ICD. This is periodically updated. Currently, the last publication is the ICD-11.

Causes

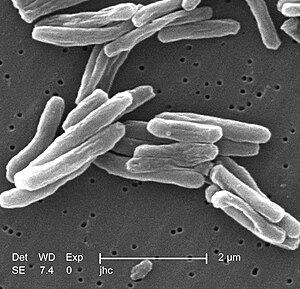

Only some diseases such as influenza are contagious and commonly believed infectious. The microorganisms that cause these diseases are known as pathogens and include varieties of bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and fungi. Infectious diseases can be transmitted, e.g. by hand-to-mouth contact with infectious material on surfaces, by bites of insects or other carriers of the disease, and from contaminated water or food (often via fecal contamination), etc. Also, there are sexually transmitted diseases.

In some cases, microorganisms that are not readily spread from person

to person play a role, while other diseases can be prevented or

ameliorated with appropriate nutrition or other lifestyle changes.

Some diseases, such as most (but not all) forms of cancer, heart disease, and mental disorders, are non-infectious diseases. Many non-infectious diseases have a partly or completely genetic basis and may thus be transmitted from one generation to another.

Social determinants of health

are the social conditions in which people live that determine their

health. Illnesses are generally related to social, economic, political,

and environmental circumstances. Social determinants of health have been recognized by several health organizations such as the Public Health Agency of Canada

and the World Health Organization to greatly influence collective and

personal well-being. The World Health Organization's Social Determinants

Council also recognizes Social determinants of health in poverty.

When the cause of a disease is poorly understood, societies tend to mythologize the disease or use it as a metaphor or symbol of whatever that culture considers evil. For example, until the bacterial cause of tuberculosis was discovered in 1882, experts variously ascribed the disease to heredity, a sedentary lifestyle, depressed mood, and overindulgence in sex, rich food, or alcohol, all of which were social ills at the time.

When a disease is caused by a pathogen (e.g., when the disease malaria is caused by infection by Plasmodium parasites.), the term disease

may be misleadingly used even in the scientific literature in place of

its causal agent, the pathogen. This language habit can cause confusion

in the communication of the cause and effect principle in epidemiology, and as such it should be strongly discouraged.

Types of causes

- Airborne

- An airborne disease is any disease that is caused by pathogens and transmitted through the air.

- Foodborne

- Foodborne illness

or food poisoning is any illness resulting from the consumption of food

contaminated with pathogenic bacteria, toxins, viruses, prions or

parasites.

- Infectious

- Infectious diseases,

also known as transmissible diseases or communicable diseases, comprise

clinically evident illness (i.e., characteristic medical signs or

symptoms of disease) resulting from the infection, presence and growth

of pathogenic biological agents in an individual host organism. Included

in this category are contagious diseases – an infection, such as influenza or the common cold, that commonly spreads from one person to another – and communicable diseases – a disease that can spread from one person to another, but does not necessarily spread through everyday contact.

- Lifestyle

- A lifestyle disease

is any disease that appears to increase in frequency as countries

become more industrialized and people live longer, especially if the

risk factors include behavioral choices like a sedentary lifestyle or a

diet high in unhealthful foods such as refined carbohydrates, trans

fats, or alcoholic beverages.

- Non-communicable

- A non-communicable disease

is a medical condition or disease that is non-transmissible.

Non-communicable diseases cannot be spread directly from one person to

another. Heart disease and cancer are examples of non-communicable diseases in humans.

Prevention

Many diseases and disorders can be prevented through a variety of means. These include sanitation, proper nutrition, adequate exercise, vaccinations and other self-care and public health measures, such as obligatory face mask mandates.

Treatments

Medical therapies

or treatments are efforts to cure or improve a disease or other health

problems. In the medical field, therapy is synonymous with the word treatment. Among psychologists, the term may refer specifically to psychotherapy or "talk therapy". Common treatments include medications, surgery, medical devices, and self-care. Treatments may be provided by an organized health care system, or informally, by the patient or family members.

Preventive healthcare

is a way to avoid an injury, sickness, or disease in the first place. A

treatment or cure is applied after a medical problem has already

started. A treatment attempts to improve or remove a problem, but

treatments may not produce permanent cures, especially in chronic diseases. Cures

are a subset of treatments that reverse diseases completely or end

medical problems permanently. Many diseases that cannot be completely

cured are still treatable. Pain management

(also called pain medicine) is that branch of medicine employing an

interdisciplinary approach to the relief of pain and improvement in the

quality of life of those living with pain.

Treatment for medical emergencies must be provided promptly, often through an emergency department or, in less critical situations, through an urgent care facility.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study of the factors that cause or encourage

diseases. Some diseases are more common in certain geographic areas,

among people with certain genetic or socioeconomic characteristics, or

at different times of the year.

Epidemiology is considered a cornerstone methodology of public health research and is highly regarded in evidence-based medicine for identifying risk factors for diseases. In the study of communicable and non-communicable diseases, the work of epidemiologists ranges from outbreak

investigation to study design, data collection, and analysis including

the development of statistical models to test hypotheses and the

documentation of results for submission to peer-reviewed journals.

Epidemiologists also study the interaction of diseases in a population, a

condition known as a syndemic. Epidemiologists rely on a number of other scientific disciplines such as biology (to better understand disease processes), biostatistics (the current raw information available), Geographic Information Science (to store data and map disease patterns) and social science

disciplines (to better understand proximate and distal risk factors).

Epidemiology can help identify causes as well as guide prevention

efforts.

In studying diseases, epidemiology faces the challenge of

defining them. Especially for poorly understood diseases, different

groups might use significantly different definitions. Without an

agreed-on definition, different researchers may report different numbers

of cases and characteristics of the disease.

Some morbidity databases are compiled with data supplied by states and territories health authorities, at national levels or larger scale (such as European Hospital Morbidity Database (HMDB))

which may contain hospital discharge data by detailed diagnosis, age

and sex. The European HMDB data was submitted by European countries to

the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

Burdens of disease

Disease burden is the impact of a health problem in an area measured by financial cost, mortality, morbidity, or other indicators.

There are several measures used to quantify the burden imposed by diseases on people. The years of potential life lost

(YPLL) is a simple estimate of the number of years that a person's life

was shortened due to a disease. For example, if a person dies at the

age of 65 from a disease, and would probably have lived until age 80

without that disease, then that disease has caused a loss of 15 years of

potential life. YPLL measurements do not account for how disabled a

person is before dying, so the measurement treats a person who dies

suddenly and a person who died at the same age after decades of illness

as equivalent. In 2004, the World Health Organization calculated that 932 million years of potential life were lost to premature death.

The quality-adjusted life year (QALY) and disability-adjusted life year

(DALY) metrics are similar but take into account whether the person was

healthy after diagnosis. In addition to the number of years lost due

to premature death, these measurements add part of the years lost to

being sick. Unlike YPLL, these measurements show the burden imposed on

people who are very sick, but who live a normal lifespan. A disease

that has high morbidity, but low mortality, has a high DALY and a low

YPLL. In 2004, the World Health Organization calculated that 1.5

billion disability-adjusted life years were lost to disease and injury. In the developed world, heart disease and stroke cause the most loss of life, but neuropsychiatric conditions like major depressive disorder cause the most years lost to being sick.

Society and culture

How a society responds to diseases is the subject of medical sociology.

A condition may be considered a disease in some cultures or eras but not in others. For example, obesity can represent wealth and abundance, and is a status symbol in famine-prone areas and some places hard-hit by HIV/AIDS. Epilepsy is considered a sign of spiritual gifts among the Hmong people.

Sickness confers the social legitimization of certain benefits,

such as illness benefits, work avoidance, and being looked after by

others. The person who is sick takes on a social role called the sick role. A person who responds to a dreaded disease, such as cancer, in a culturally acceptable fashion may be publicly and privately honored with higher social status.

In return for these benefits, the sick person is obligated to seek

treatment and work to become well once more. As a comparison, consider pregnancy, which is not interpreted as a disease or sickness, even if the mother and baby may both benefit from medical care.

Most religions grant exceptions from religious duties to people

who are sick. For example, one whose life would be endangered by fasting on Yom Kippur or during Ramadan

is exempted from the requirement, or even forbidden from participating.

People who are sick are also exempted from social duties. For

example, ill health is the only socially acceptable reason for an

American to refuse an invitation to the White House.

The identification of a condition as a disease, rather than as

simply a variation of human structure or function, can have significant

social or economic implications. The controversial recognition of

diseases such as repetitive stress injury (RSI) and post-traumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) has had a number of positive and negative effects on the

financial and other responsibilities of governments, corporations, and

institutions towards individuals, as well as on the individuals

themselves. The social implication of viewing aging as a disease could be profound, though this classification is not yet widespread.

Lepers were people who were historically shunned because they had an infectious disease, and the term "leper" still evokes social stigma. Fear of disease can still be a widespread social phenomenon, though not all diseases evoke extreme social stigma.

Social standing and economic status affect health. Diseases of poverty are diseases that are associated with poverty and low social status; diseases of affluence

are diseases that are associated with high social and economic status.

Which diseases are associated with which states vary according to time,

place, and technology. Some diseases, such as diabetes mellitus,

may be associated with both poverty (poor food choices) and affluence

(long lifespans and sedentary lifestyles), through different mechanisms.

The term lifestyle diseases describes diseases associated with longevity and that are more common among older people. For example, cancer

is far more common in societies in which most members live until they

reach the age of 80 than in societies in which most members die before

they reach the age of 50.

Language of disease

An illness narrative is a way of organizing a medical experience into a coherent story that illustrates the sick individual's personal experience.

People use metaphors to make sense of their experiences with disease. The metaphors move disease from an objective thing that exists to an affective experience. The most popular metaphors draw on military

concepts: Disease is an enemy that must be feared, fought, battled,

and routed. The patient or the healthcare provider is a warrior, rather

than a passive victim or bystander. The agents of communicable diseases

are invaders; non-communicable diseases constitute internal

insurrection or civil war. Because the threat is urgent, perhaps a

matter of life and death, unthinkably radical, even oppressive, measures

are society's and the patient's moral duty as they courageously

mobilize to struggle against destruction. The War on Cancer is an example of this metaphorical use of language. This language is empowering to some patients, but leaves others feeling like they are failures.

Another class of metaphors describes the experience of illness as

a journey: The person travels to or from a place of disease, and

changes himself, discovers new information, or increases his experience

along the way. He may travel "on the road to recovery" or make changes

to "get on the right track" or choose "pathways".

Some are explicitly immigration-themed: the patient has been exiled

from the home territory of health to the land of the ill, changing

identity and relationships in the process. This language is more common among British healthcare professionals than the language of physical aggression.

Some metaphors are disease-specific. Slavery is a common metaphor for addictions:

The alcoholic is enslaved by drink, and the smoker is captive to

nicotine. Some cancer patients treat the loss of their hair from chemotherapy as a metonymy or metaphor for all the losses caused by the disease.

Some diseases are used as metaphors for social ills: "Cancer" is

a common description for anything that is endemic and destructive in

society, such as poverty, injustice, or racism. AIDS was seen as a

divine judgment for moral decadence, and only by purging itself from the

"pollution" of the "invader" could society become healthy again. More recently, when AIDS seemed less threatening, this type of emotive language was applied to avian flu and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Authors in the 19th century commonly used tuberculosis as a symbol and a metaphor for transcendence.

Victims of the disease were portrayed in literature as having risen

above daily life to become ephemeral objects of spiritual or artistic

achievement. In the 20th century, after its cause was better

understood, the same disease became the emblem of poverty, squalor, and

other social problems.